Law Student Stress Management Strategies

Law students must deal with high academic expectations, heavy workloads, competitive environments, and uncertain career prospects. They also must balance their studies with their personal and professional obligations, such as family, friends, jobs, or extracurricular activities. These sources of stress can affect the mental and physical health of law students, as well as their academic performance and satisfaction. Thus, law school presents the perfect opportunity for each law student to develop self-care and stress management strategies that they can use both during law school and to take forward into their future lives as lawyers.

In 2024, the LSSSE Student Stress module began asking students about specific coping strategies they use for stress and anxiety. Although some strategies provided on the survey are healthier than others, they all represent ways students may try to manage their stress and anxiety levels. Gathering these data can provide a starting point for law schools to take the pulse of their students’ mental health and to consider ways to support their students more effectively.

On the survey, students can select as many stress and anxiety management options as they wish. Exercise and seeking social support are the most commonly used stress management strategies, with 77% of students exercising to reduce stress and around 75% of students talking about their troubles with a friend or family member. A little more than half of students engage in procrastination (57%) to manage stress and 53% engage in a hobby. Negative self-talk and alcohol or other recreational drugs are the least common stress reduction techniques, with slightly more than a quarter (27%) of law students using them.

Law schools are increasingly concerned about making sure their students are learning healthy stress management and coping strategies and for good reason, given the substance use and mental health challenges that disproportionately affect lawyers, relative to the general population. Mindfulness and meditation in particular are gaining traction because they are proven techniques that can improve mental health, enhance focus, and promote well-being. Some law schools are offering workshops, courses, or online resources on mindfulness and meditation for their students, as well as creating spaces where students can practice these techniques. Whatever strategies law students adopt, law students who understand what they can do to regulate their negative emotions and stress responses will be better positioned to learn more deeply in law school and to perform their best as law students and as lawyers.

A Long-Term Look at Relationships with Law School Faculty and Administrators, 2004-2023

In our last post, we examined how peer relationships between law students have changed over the last twenty years. Now we will consider the relationships between law students and their faculty and administrators over the same period.

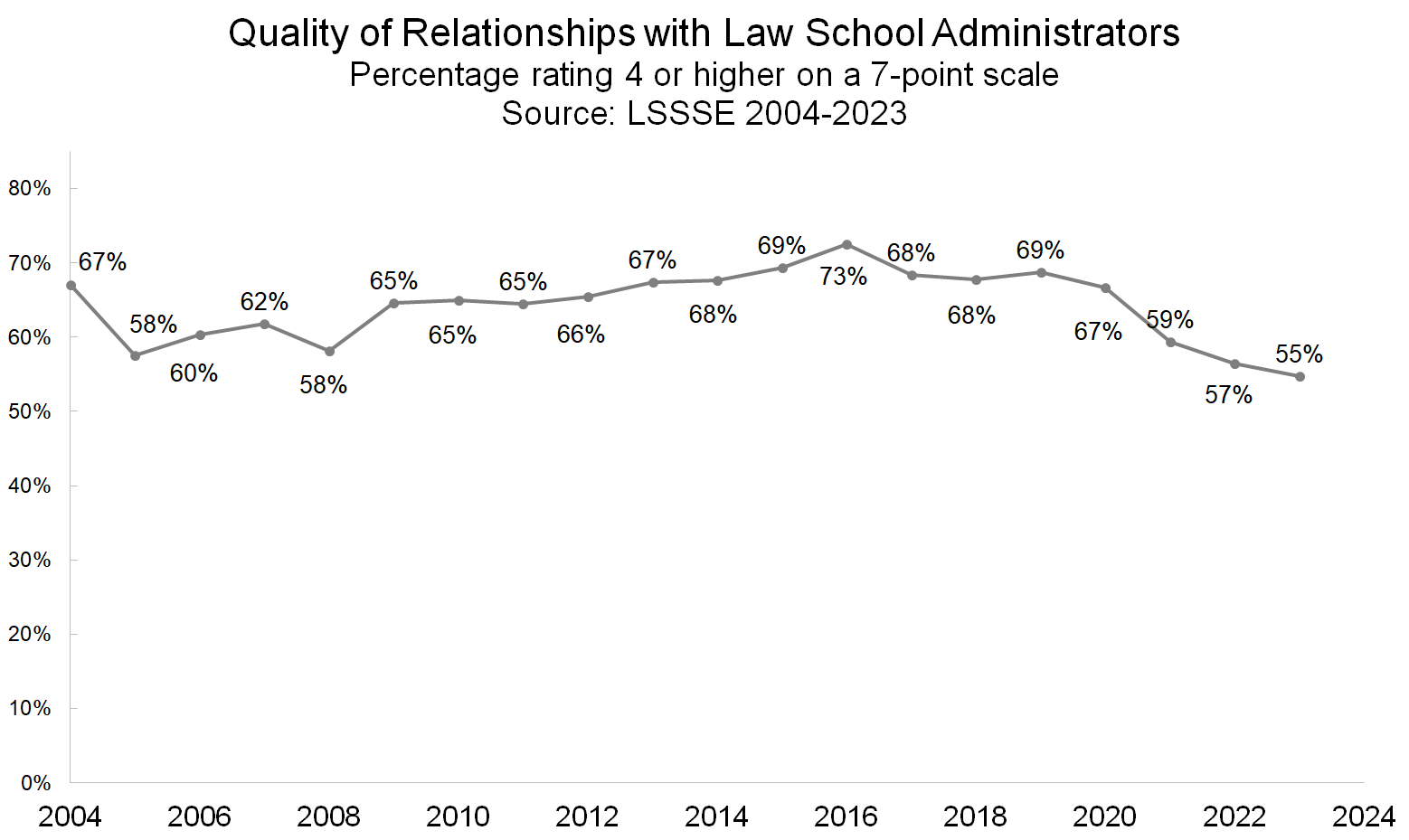

Generally, law students have better relationships with faculty than administrators. In 2023, 71% of law students were satisfied with their relationships with faculty (rated 5 or higher on a 7-point scale) compared to only 55% of students who were satisfied with their relationships with law school administrators.

Much like satisfaction with peer relationships, satisfaction with faculty relationships has fluctuated over the last twenty years and may be a bit on the decline in recent years. Satisfaction with relationships with faculty hit an all-time high in 2016 at 80% but has been below the average of 75% since 2021.

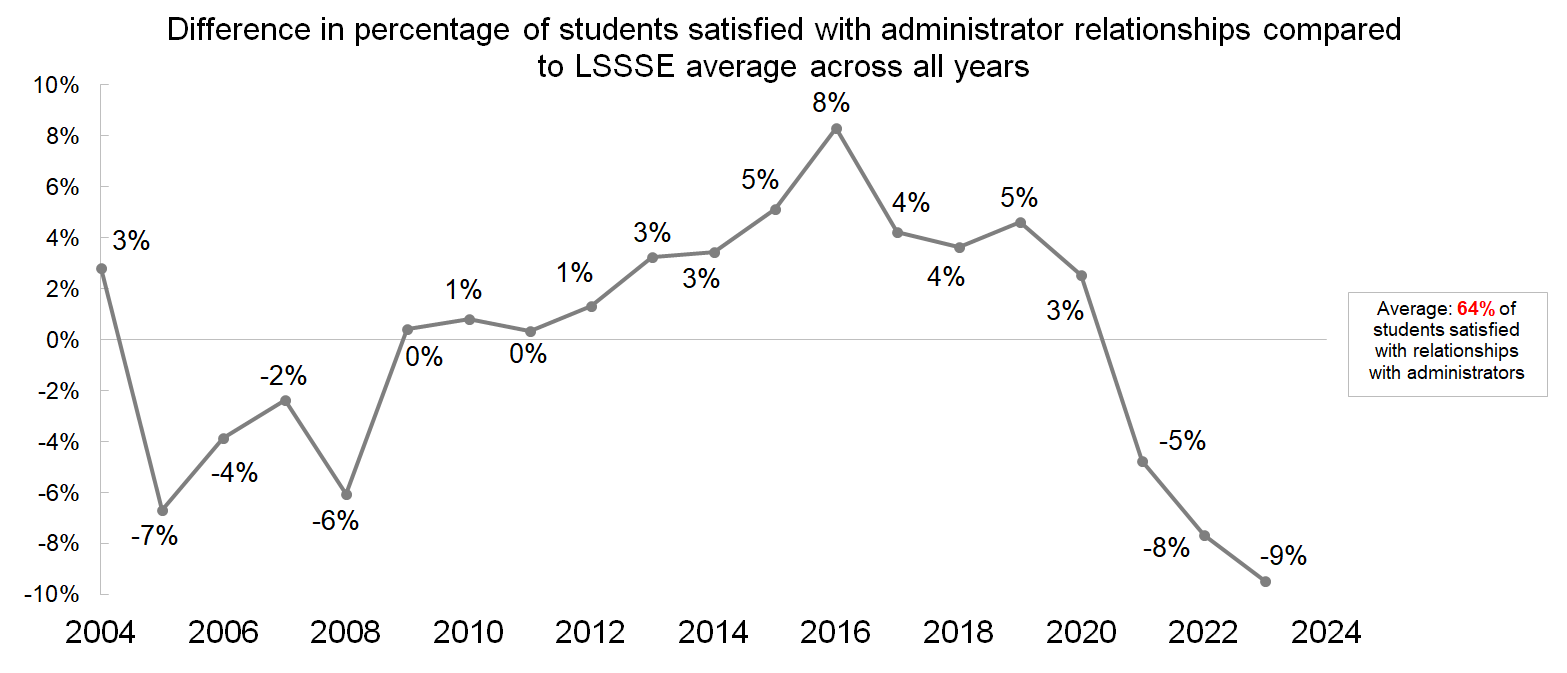

This next graph gives us the ability to look specifically at the difference between satisfaction with faculty relationships and the all-time average (75%) for all years since the inaugural LSSSE survey in 2004.

Students’ outlook on their relationships with administrators is even bleaker. The 2023 satisfaction rate of 55% is a full nine percentage points lower than the all-time average of 64%, and eighteen percentage points lower than the peak value of 73% in 2016. Although all law student relationships have been on a downward trajectory over the last few years, the relationships between students and administrators have been most strongly impacted and thus requires some special thought and attention by law schools. Perhaps the disruptions brought by COVID-19 have isolated students most severely from their administrators or perhaps the genesis of this discontent lies elsewhere.

Satisfaction with relationships with administrators has been on a precipitous decline since 2016.

It makes sense that students have stronger relationships with faculty since students see faculty on a regular basis and are likely to come to rely on faculty for academic guidance, feedback, and mentoring. Students and faculty are united in a common goal to study and understand the law, which can foster positive regard. Administrators, conversely, may be regarded as more impersonal given that their impact on the students' learning experience is more remote. Administrators may also be responsible for implementing rules and policies with which the students may not always agree. Hence, law students may understandably experience higher levels of rapport and satisfaction with their faculty than their administrators. However, given that law students’ relationships with administrators is currently at an all-time low, it may be worth some reflection to see how law school administrators came become more engaged to make a positive impact on the lives of their students.

A Long-Term Look at Relationships with Law School Peers, 2004-2023

A common misconception about law students is that their competition with each other for grades, jobs, and prestige creates a stressful and hostile law school environment. However, this is not the case for most law students who often find opportunities for support and friendship among their peers. Law students share common challenges and goals, and they can benefit from exchanging ideas and resources with each other. Many law schools also foster a culture of collegiality and mutual respect, where students are encouraged to help each other and celebrate each other's achievements. Rather than being a source of stress, peer relationships can be a source of resilience and well-being for law students. In fact, LSSSE data from 2023 show that only 38% of law students experienced quite a bit or very much stress or anxiety because of competition with peers. They are far more likely to be substantially stressed by academic performance (80% of students) and academic workload (79% of students).

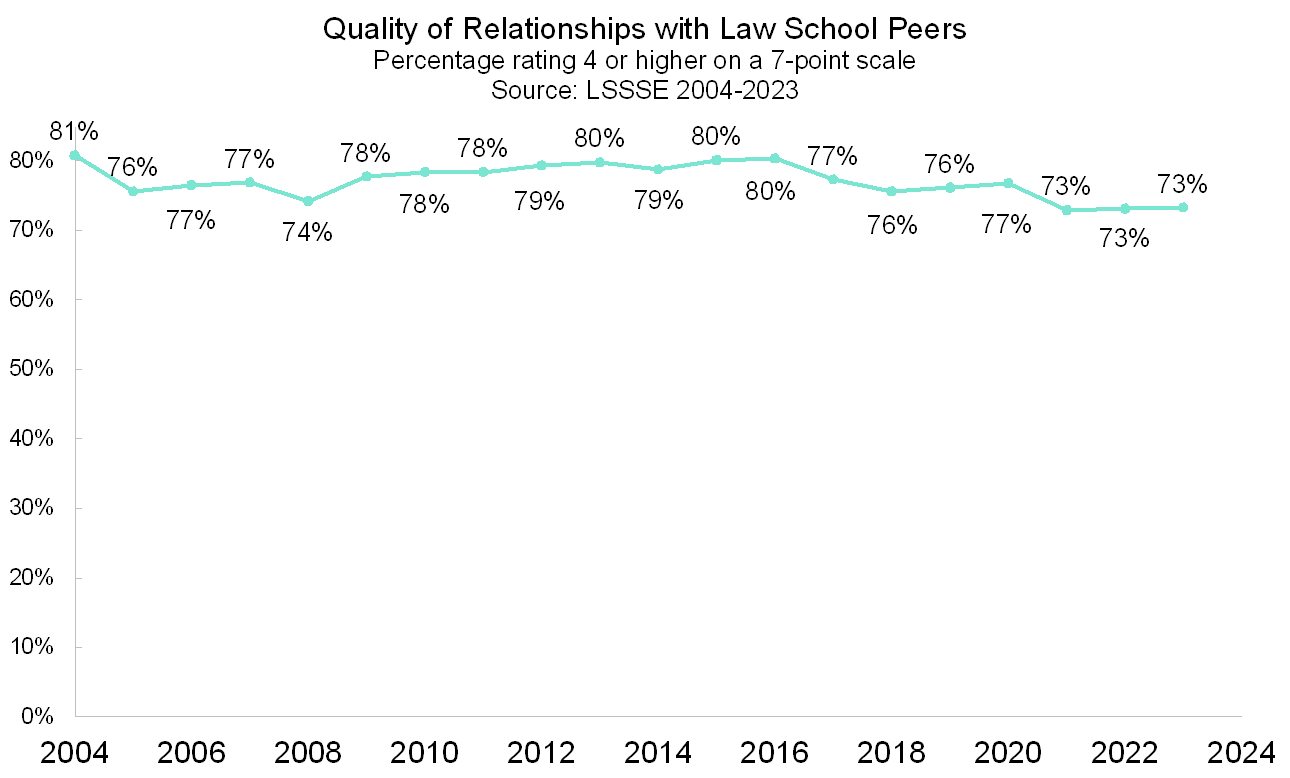

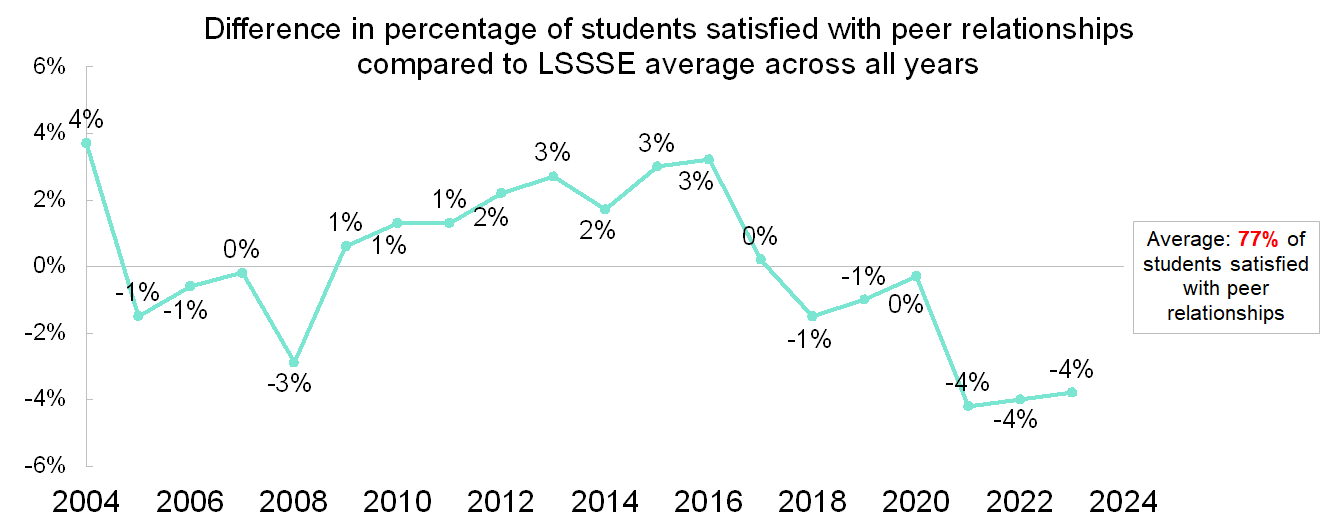

Since the 2004 LSSSE inaugural survey, an average of 77% of law students have said that their overall relationships with other students are mostly positive (at least a 4 on a 7-point scale). This number has fluctuated over time, with 81% of students having mostly positive relationships in 2004 and 73% of students feeling similarly in 2023.

If we compare the percentage of students having an overall positive relationship with peers to the all-time LSSSE national average of 77%, we can see that the last several years have had slightly lower levels of peer satisfaction.

Although satisfaction with peer relationships was already on a somewhat downward trajectory before COVID-19, the notable decrease in relationship satisfaction during the 2020-2021 academic year may be largely driven by the decrease in relationship satisfaction among 1L students. In the spring of 2020 (largely before COVID-19 shutdowns started), 80% of 1L students were satisfied with their relationships with their fellow students. In the spring of 2021 after a year of huge disruptions in the law school environment including widespread online learning, only 72% of 1L students felt this way. However, 74% of 3L students were satisfied with their peer relationships in 2020 and again 74% of 3L students felt this way in 2021. Students who were introduced to law school in a time of necessary isolation were understandably somewhat less able to bond with their classmates. Orientation programs, study groups, moot courts, clinics, extracurriculars, and informal gatherings were either canceled, restricted, or moved online. These disruptions may have hindered the ability of 1L students to establish friendships and build rapport. Furthermore, online learning may have decreased the frequency and quality of interactions among students, as well as the sense of belonging and community that stems from being physically present in a shared space. Nevertheless, relationships among law students remained positive overall, showing that even the limitations of pandemic life did not prevent characteristically creative and resilient law students from forging relationships with each other. It will be interesting to examine how law students feel about their relationships with each other in future years now that life has largely returned to the pre-pandemic normal.

Focus on First-Generation Students, Part 2

In our last post, we shared some of the demographic characteristics of first-gen law students, which we define as law students who do not have at least one parent with a bachelor’s degree. In this post, we will dig deeper into the first-gen law student experience and how it differs from the experiences of non-first-gen law students.

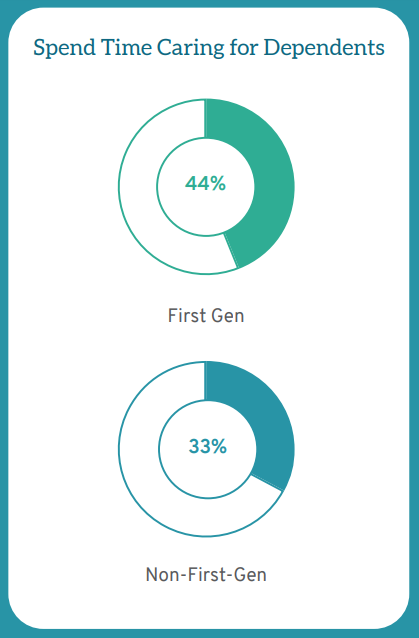

Time Usage

LSSSE asks students to estimate the average number of hours they spend each week engaging in activities that are directly and indirectly related to the educational experience. Time usage is important because it reflects students’ academic engagement and overall priorities. First-gen students are more likely to attend law school part-time, which suggests that they have complicated schedules with competing demands, rather than a sole focus on law school. LSSSE data show that high percentages of first-gen students have familial obligations as caretakers for dependents living in their household. Forty-four percent (44%) of first-gen students spend time caring for dependents, compared to 33% of non-first-gen students.

First-gen students are just as engaged as their non-first-gen peers in academic pursuits outside of class, despite the fact that they have more responsibilities competing for their time. First-gen students work with students and faculty on group projects at equal or greater levels relative to non-first-gen students. Roughly equal percentages of first-gen students (19%) and non-first-gen students (18%) report that they frequently work with faculty members on activities other than coursework (including committees, orientation, student life activities, etc.). Likewise, 33% of first-gen (and 31% of non-first-gen) students frequently work with classmates outside of class to prepare assignments. The diligence of first-gen students is particularly impressive given their personal obligations. One third (33%) of first-gen students always come to class fully prepared despite their family duties and work schedules, the same percentage as non-first-gen students (who tend to work less and have fewer familial obligations).

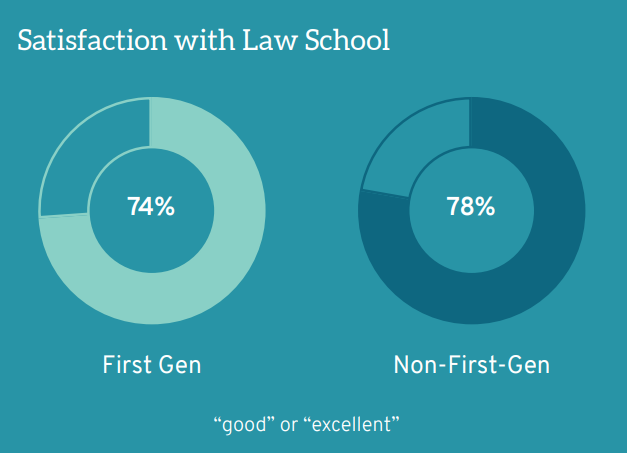

Satisfaction

First-gen students, like law students overall, are overwhelmingly satisfied with their law school experience. Seventy-four percent (74%) of first-gen students evaluate the educational experience at their law school as “good” or “excellent,” similar to non-first-gen students (78%). Furthermore, 77% of first-gen (and 79% of non-first-gen) students report they would choose to attend the same law school again, with the benefit of hindsight. These trends are particularly noteworthy given the increased financial risks and other sacrifices made by first-gen students to attend law school.

First-gen students face unique challenges and responsibilities as they navigate legal education. Law schools should take the findings from this Annual Report, as well as their own school-specific LSSSE data, to craft targeted programs to support first-gen students. Better supporting them personally will free up time and resources for first-gen students to devote to not only academics, but other co-curricular pursuits so they are optimally placed to thrive as they enter the legal profession.

Focus on First-Generation Students, Part 1

Our next two blog posts will provide selected snippets from the LSSSE 2024 Annual Report: Focus on First-Generation Students. To read the entire report, please visit our website.

First-Gen Demographics

First-generation (first-gen) students are trailblazers for their families. They attend college without the guidance of a parent who has completed their own bachelor’s degree. Decades of research show that first-gen students overcome significant challenges simply to gain access to college and invest even more to persist until degree completion. First-gen students tend to enter higher education with fewer financial resources and less social and cultural capital than those who have at least one parent who completed a college degree. Although first-gen students have already drawn on their resiliency and determination to adapt to college life, law school brings its own cultural norms and ways of learning that are, again, likely to be unfamiliar.

Despite these expected challenges, few studies focus on the experiences of first-gen students in law school. In 2014, LSSSE was one of the first organizations in legal education to collect data on first-gen students by adding a survey question about parental education. The data LSSSE has collected shed light on how first-gen students engage with law school and how their experiences differ from those of their non-first-gen classmates.

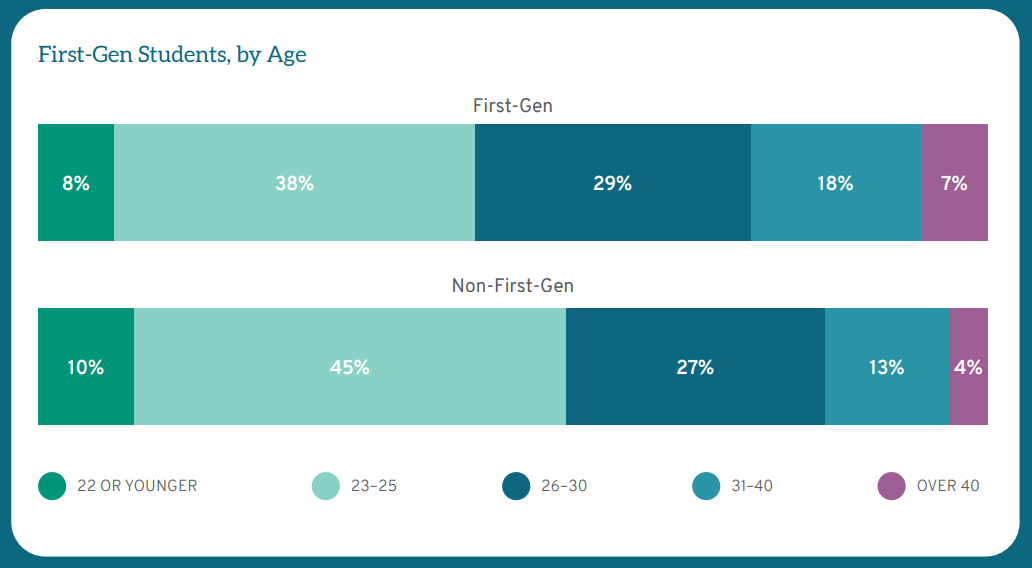

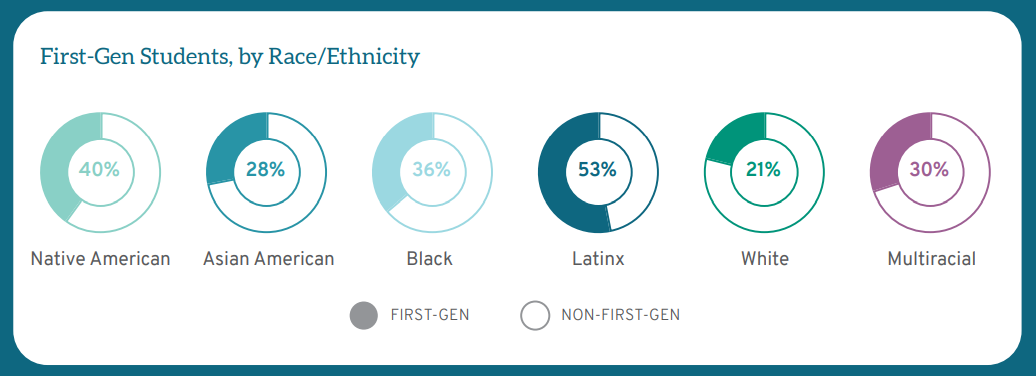

For LSSSE analyses, students who respond that neither parent received a bachelor’s degree or higher are considered first-gen students. First-gen students comprise over one-quarter (26%) of the LSSSE respondents. First-gen students tend to be different from non-first-gen students in important ways, including race, gender, age, and a full-time focus on law school. Students of color from every racial group are more likely than White students to be first-gen. For instance, 53% of Latinx respondents and 36% of Black respondents are first-gen, compared with 21% of White respondents. Twenty-eight percent (28%) of women are first-gen students compared to 24% of men. First-gen students also tend to be older, with 54% of first-gen students being over the age of 25 compared to 44% of non-first-gen students. Finally, while the vast majority of law students in the U.S. study on a full-time basis, first-gen students are more likely to study part-time by about 10 percentage points. Thus, in addition to their first-gen status, many of these students have other demographic differences from the average law student.

First-Gen Student Debt

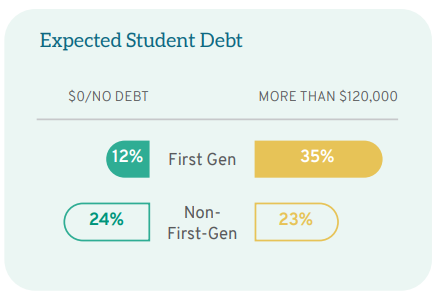

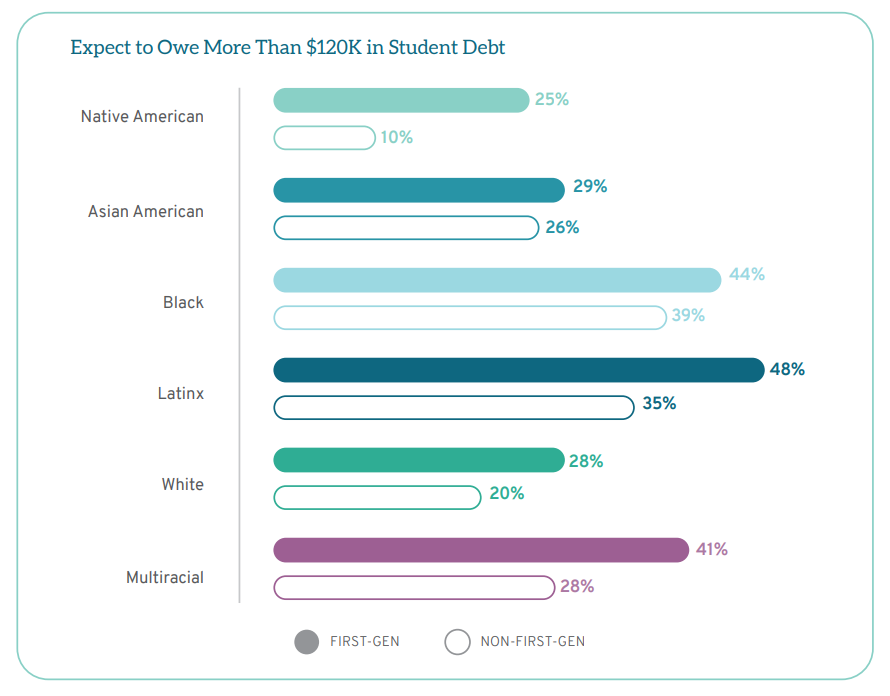

Parental education is often used as a proxy for socioeconomic status. A college degree has a significant positive impact on salary and career earnings over a lifetime. On average, first-gen students come from families that earn less than the families of students with a parent who completed college. Because first-gen students enter law school with lower undergraduate GPA and LSAT scores and because higher LSAT scores result in greater success with scholarships, first-gen students are less likely to be awarded merit scholarships in law school. As a result, first-gen students rely on student loans to a greater extent than their classmates. For instance, 24% of non-first-gen students anticipate graduating with no law school debt compared to only 12% of first-gen students. Conversely, roughly one-quarter (23%) of non-first-gen students expect to graduate with more than $120,000 in student debt compared to over one-third (35%) of first-gen students. Students from the same racial background nevertheless have significant debt differentials based on whether they are first-gen students, with first-gen students of color borrowing at particularly high levels.

First-gen students differ from their non-first-gen classmates in meaningful ways. First-gen students typically are older students, many have caretaking responsibilities, and they are more likely to come from families with fewer financial resources, necessitating working while in school. Because of these differences, first-gen students bring valuable life experiences and diverse perspectives to classroom conversations. Once they complete law school, they are also equipped to bring the fruits of their legal education back to their communities. The hard work and determination that first-gen students bring to law school is nonetheless coupled with higher levels of debt than their non-first-generation peers. This creates an additional burden not only during law school but as they choose their first jobs as lawyers and continue their legal careers.

In our next blog post, we will examine how first-gen law students use their time and the degree to which they engage with different aspects of the law school experience.

Preparing Law Students for a Multicultural World

Alongside developing analytical skills and learning about the law, law students must learn how to work effectively in a diverse, multicultural environment. Law schools have a responsibility to prepare their students by providing them with the knowledge, skills, and experiences necessary to navigate complex cultural dynamics. This can be achieved through a variety of means, including offering courses on cross-cultural communication and conflict resolution, providing opportunities for international study and internships, and fostering a diverse and inclusive campus community. By equipping law students to work effectively in a multicultural world, law schools can help to ensure their graduates are well-prepared to meet the challenges of an interconnected global society.

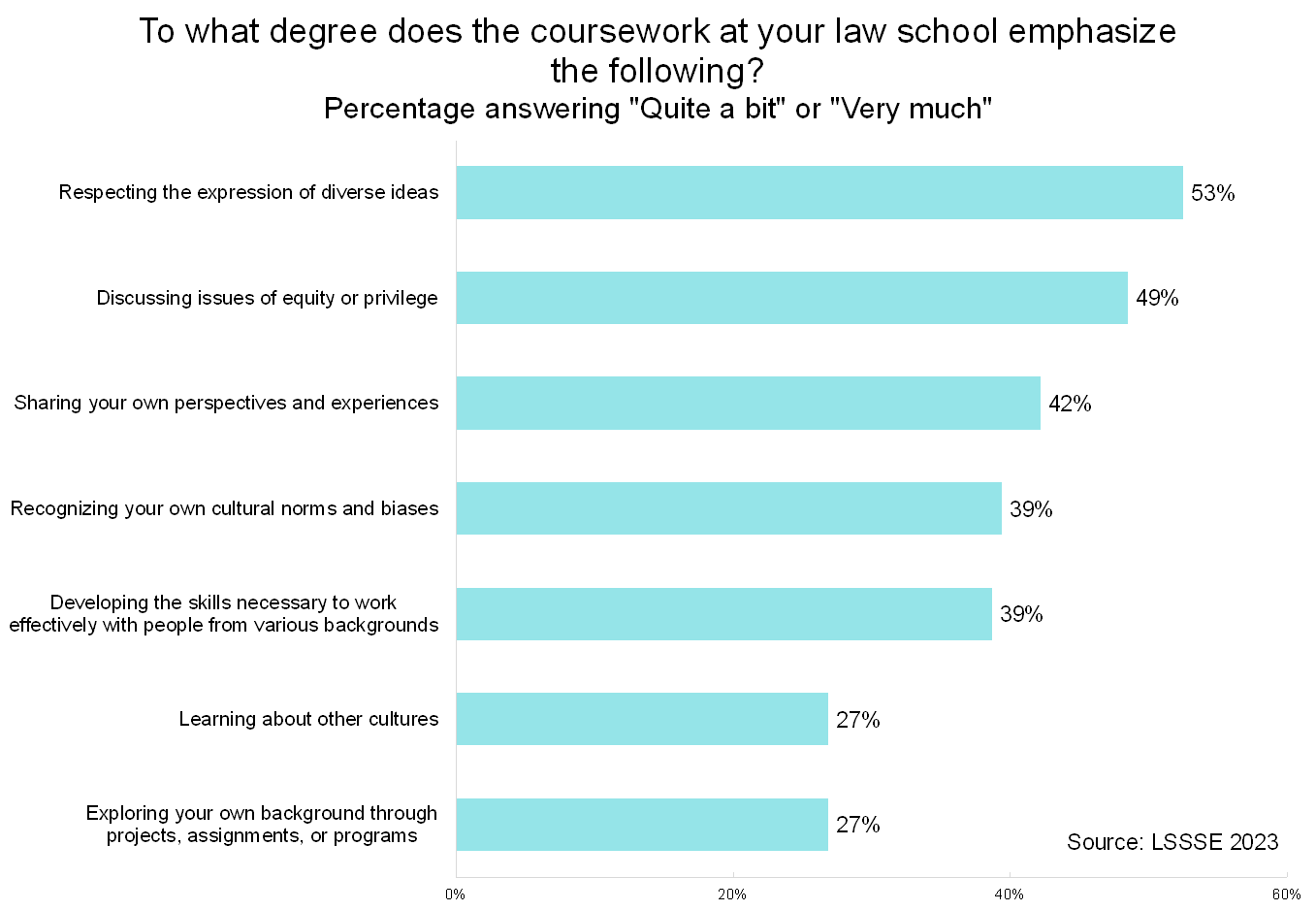

We wanted to understand the degree to which law students feel that their law school's coursework helps them learn to interact effectively and respectfully with others who are different from them. LSSSE asks students about the degree to which the coursework at their law school emphasizes various foundational principles of diversity and inclusion. In 2023, more than half of law students (53%) felt their coursework placed quite a bit or very much emphasis on respecting the expression of diverse ideas, and nearly as many (49%) experienced an emphasis on discussing issues of equity or privilege. However, only slightly more than a quarter (27%) of students felt that their law school emphasized learning about other cultures, and the same percentage felt their law school emphasized exploring students’ own backgrounds through projects, assignments, or programs

By creating a climate of academic freedom and intellectual diversity, law schools promote the values of democracy and human rights, which are essential for the rule of law and social justice. Only 14% of students said their law school placed very little emphasis on respecting the expression of diverse ideas, so clearly law schools value broader ideals around freedom of expression. However, law students also need to understand their own cultural background and how it shapes their worldview, values, and assumptions. By exploring their own identity and experiences, law students can gain insight into how they perceive themselves and others and how they relate to people who are different from them. This can help them respect and value others' contributions. Furthermore, by understanding their own cultural background, law students can also identify areas where they may need to learn more or adapt their behavior to work effectively in a multicultural context.

Courses on cultural diversity and inclusion, implicit bias, and cross-cultural communication can provide students with the knowledge and skills necessary to work effectively in a multicultural environment. Additionally, incorporating case studies and simulations that expose students to real-world scenarios can help students to develop practical skills in navigating complex cultural dynamics. By providing students with opportunities to engage in critical reflection and dialogue, law schools can help students to become more aware of their own biases and to develop strategies for mitigating their impact.

SPOTLIGHT ON: Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Law Students

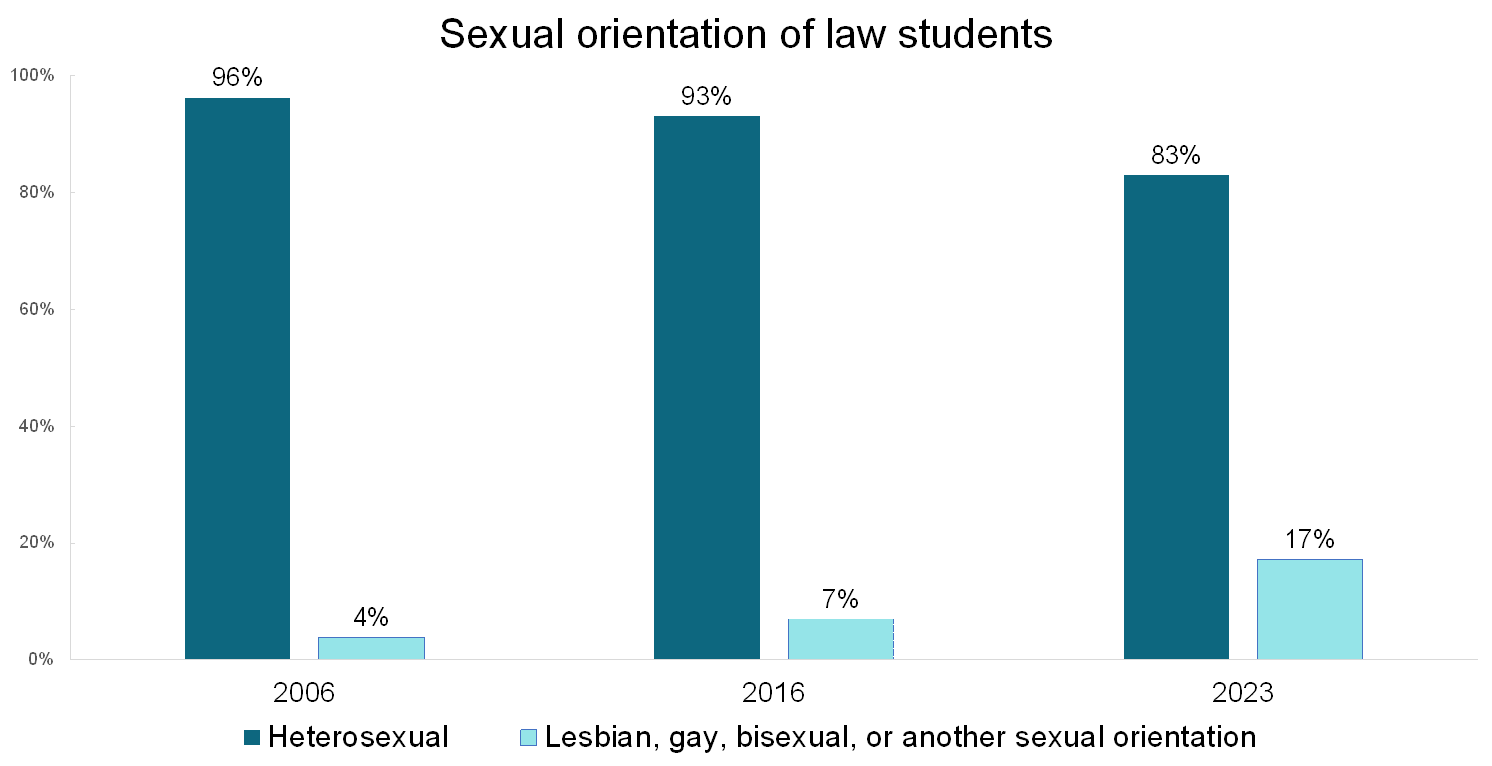

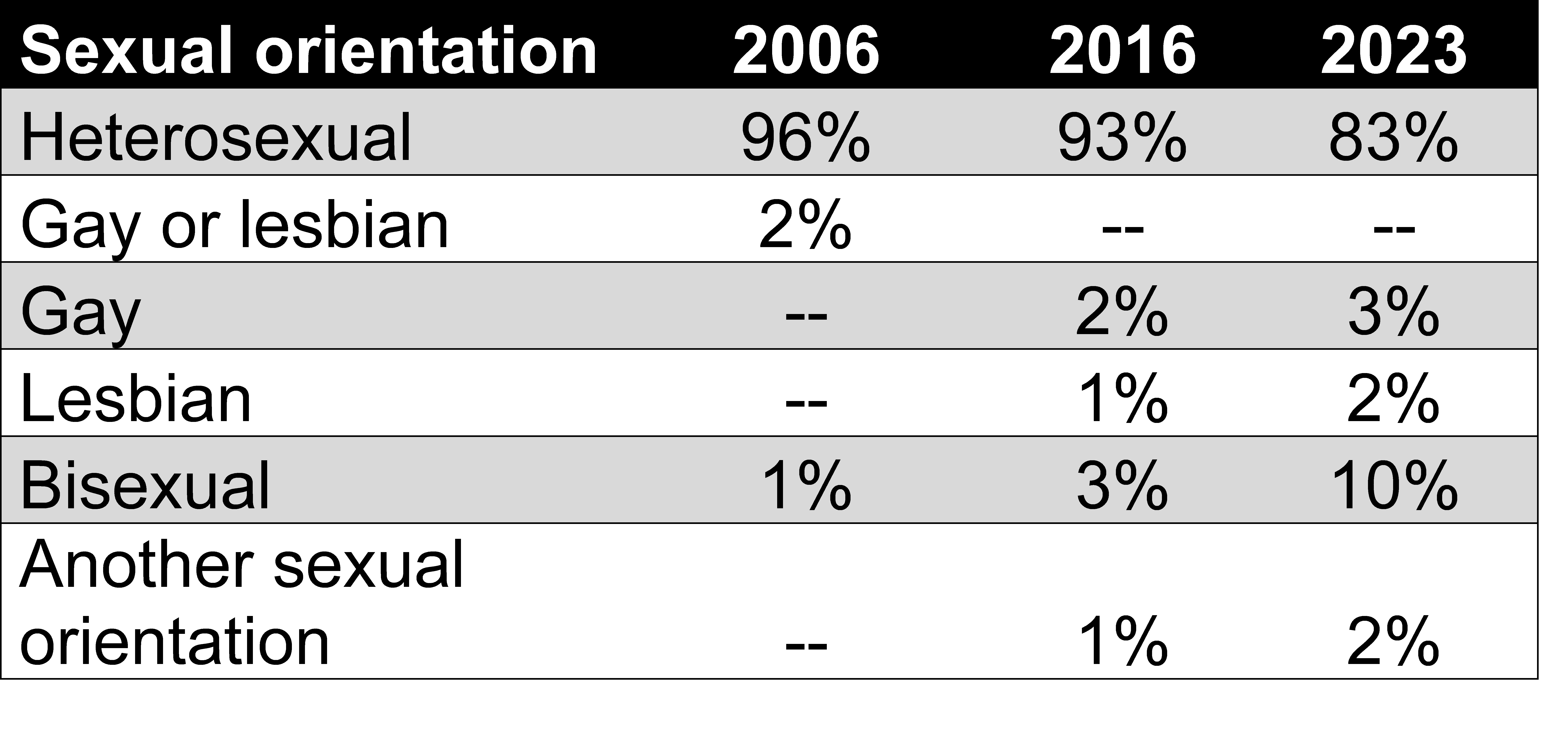

The percentage of law students who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or another non-heterosexual sexual orientation (LGB+) has grown dramatically over the last twenty years. When LSSSE first began asking about sexual orientation in 2006, 96% of law students identified as heterosexual, 2.5% were gay or lesbian, and only 1.3% were bisexual. The numbers had shifted noticeably by 2016, when the sexual orientation question was revamped slightly to be more inclusive. That year, 93% of law students were heterosexual, 2.3% were gay, 1.1% were lesbian, 2.6% were bisexual, and 0.9% were of another sexual orientation. However, by 2023, only 83% of law students identified as heterosexual. Three percent were gay, 1.7% were lesbian, 2% had another sexual orientation, and a full 10% identified as bisexual.

-- indicates response option was not available that year

-- indicates response option was not available that year

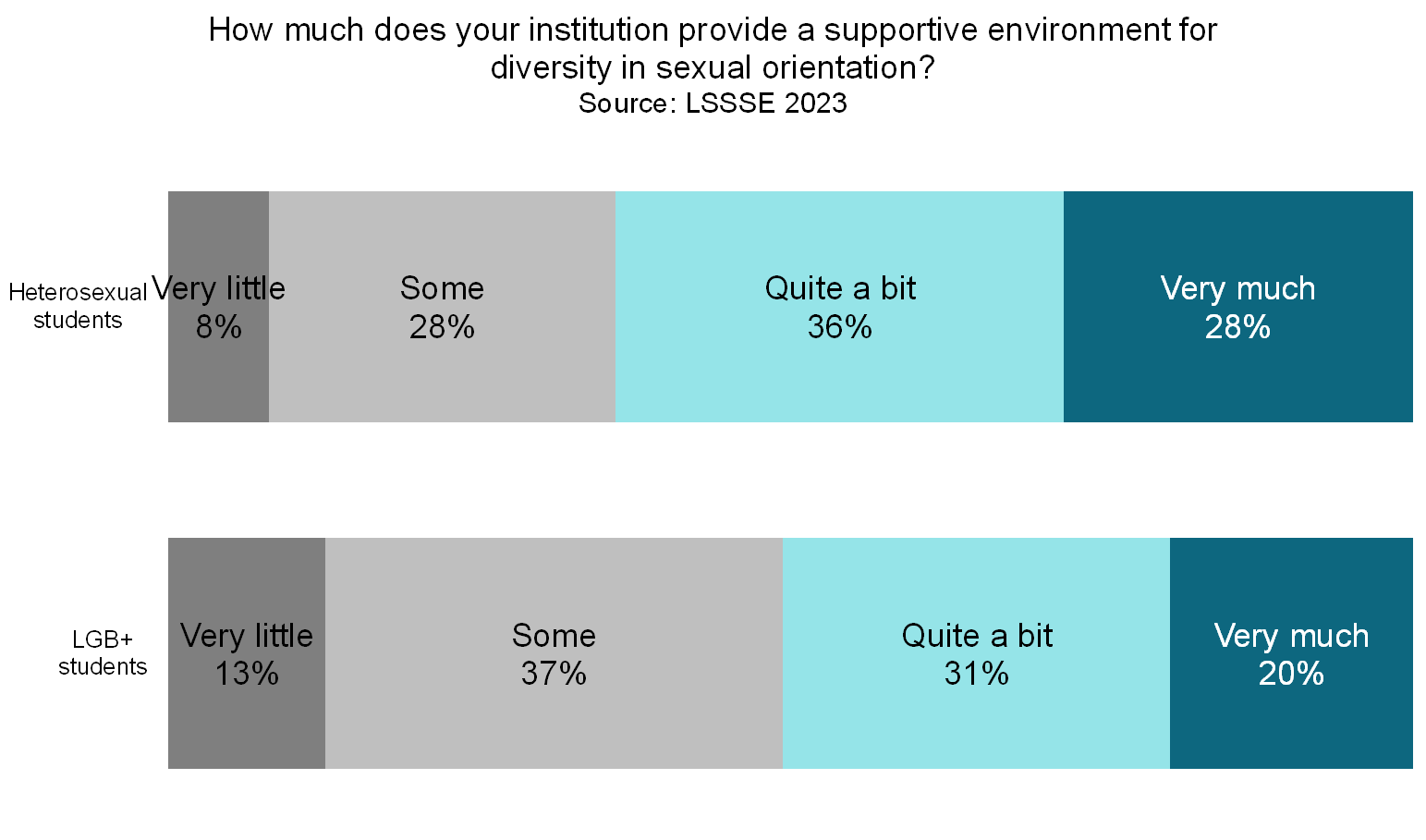

LGB+ students are somewhat less comfortable in law school relative to their heterosexual peers. For example, 72% of LGB+ students feel that they are part of the law school community compared to 77% of heterosexual students. Only half (50%) of LGB+ students believe that their law school places quite a bit or very much emphasis on ensuring that they are not stigmatized because of their identity (racial/ethnic, gender, religious, sexual orientation, etc.) compared to 61% of heterosexual students. Similarly, only about half (51%) of LGB+ students believe that their law school is a supportive environment for diversity in sexual orientation compared to just under two-thirds (64%) of heterosexual students.

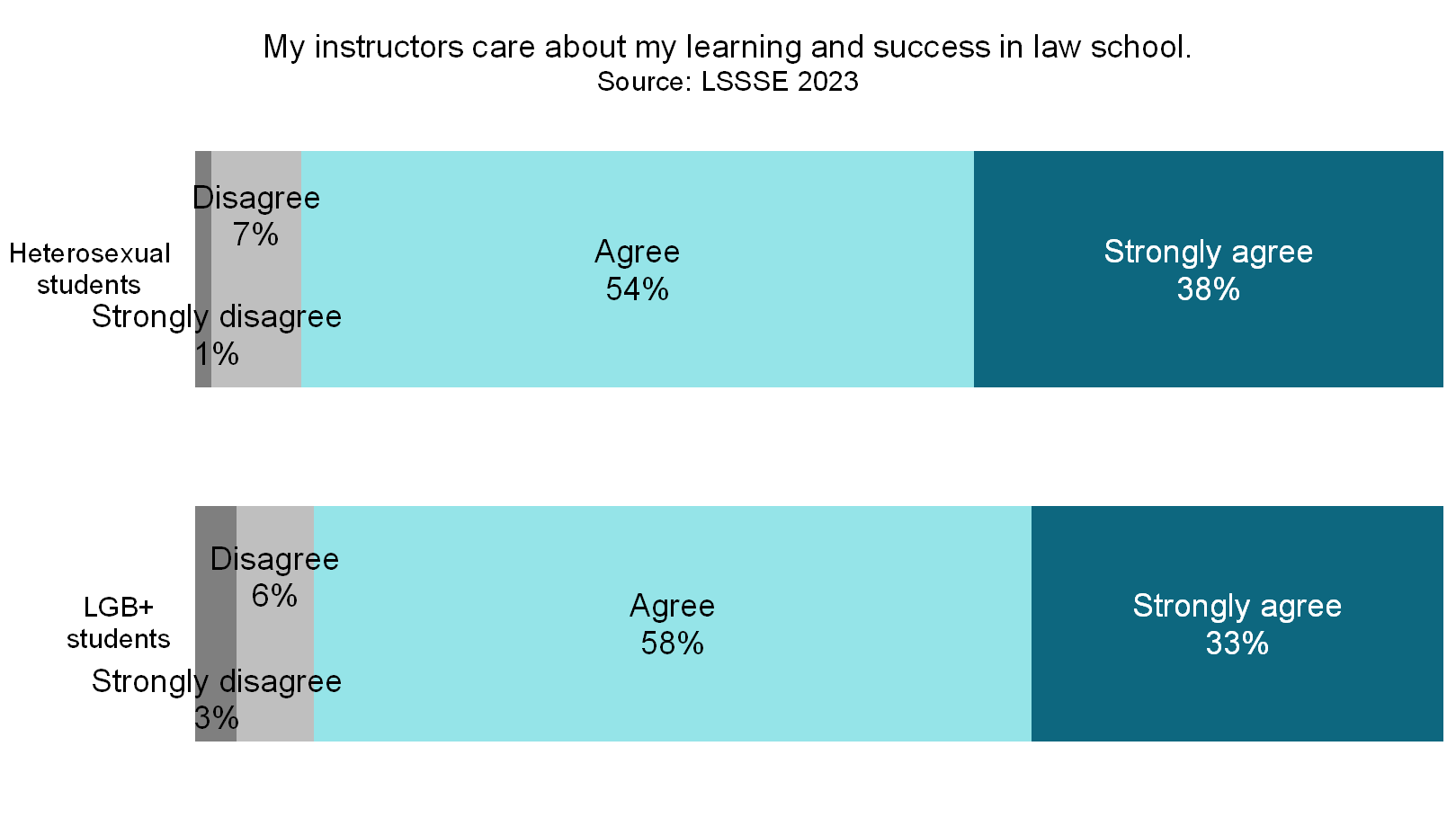

Despite the perception of a somewhat chilly climate overall, LGB+ law students are nearly equally likely as heterosexual law students to have strong relationships with law school faculty. LGB+ students rate their relationships with faculty on average 5.2 on a seven-point scale, compared to 5.3 for heterosexual students. A full 91% of LGB+ students believe their instructors care about their learning and success in law school, nearly equal to the 92% of heterosexual students who feel that way. Around four in five LGB+ and heterosexual students consider at least one instructor a mentor whom they feel comfortable asking for advice or guidance. Clearly, most students find help and support from their law school faculty, regardless of their sexual orientation.

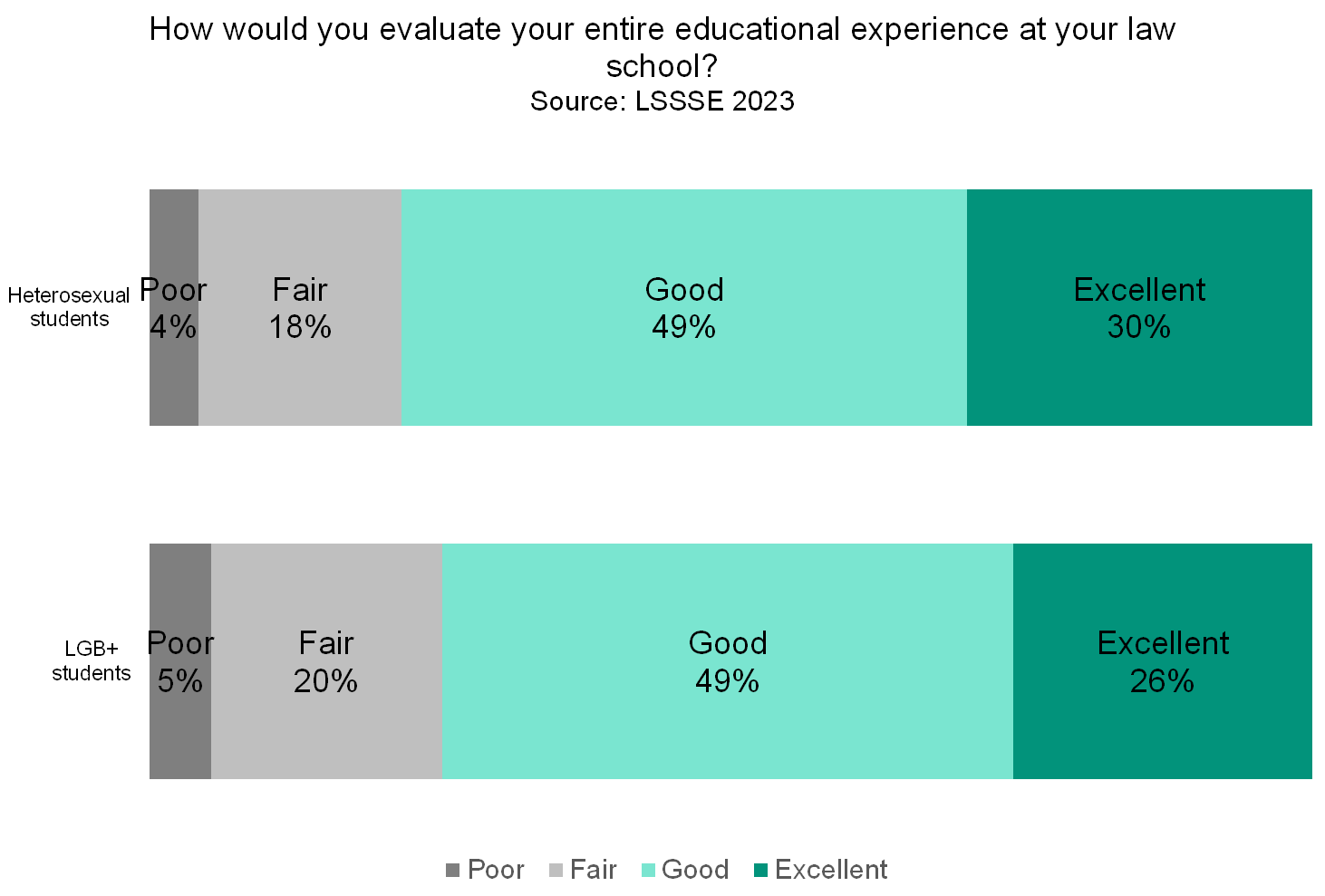

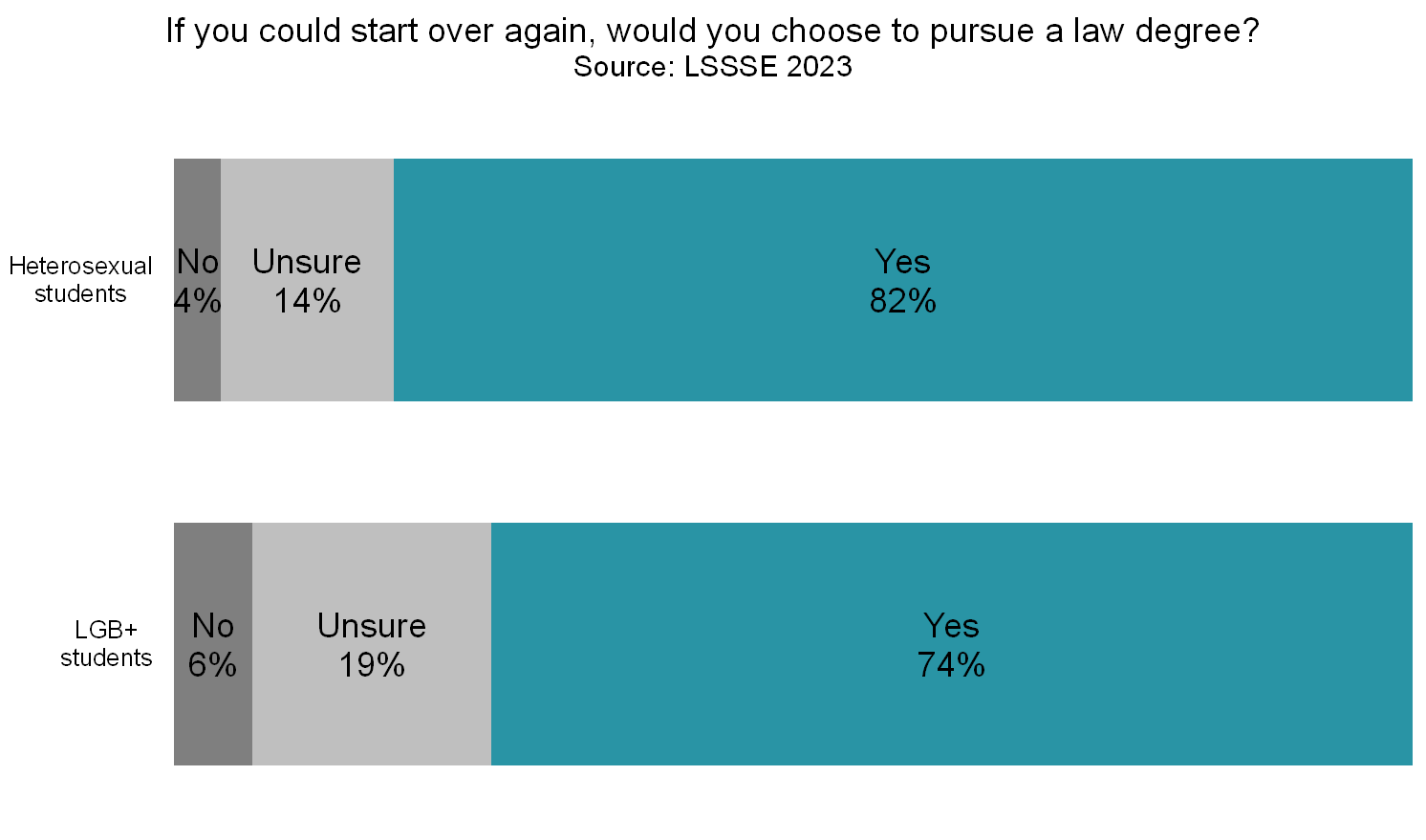

LGB+ students are somewhat less satisfied with their overall experience at law school compared to heterosexual law students. Three-quarters (75%) or LGB+ students rate their experience “good” or “excellent” compared to 78% of heterosexual students. However, LGB+ students are much less likely to be sure that they would pursue a law degree if they could start over. Just under three-quarters (74%) of LGB+ students said they would pursue a law degree and 19% were unsure. More than four in five (82%) heterosexual students would choose law school again and only 14% were unsure. Clearly, LGB+ law students are more likely than heterosexual law students to have regrets or misgivings about the path they selected.

Given that the population of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and other non-heterosexual students is growing rapidly in law schools, the concerns that these students have about the law school experience deserve particularly careful attention. LGB+ law students are less likely to feel that they belong, more likely to feel stigmatized, and more likely to question whether attending law school was the correct choice for them. Interestingly, most LGB+ students feel that their instructors care, and they are equally likely as heterosexual students to have an instructor that they consider a mentor. Perhaps law schools can use these personal connections to identify and address the concerns of their lesbian, gay, bisexual, and other non-heterosexual students in order to ensure equitable educational opportunities and a more supportive law school environment.

Extracurricular Activity Participation Among JD Students

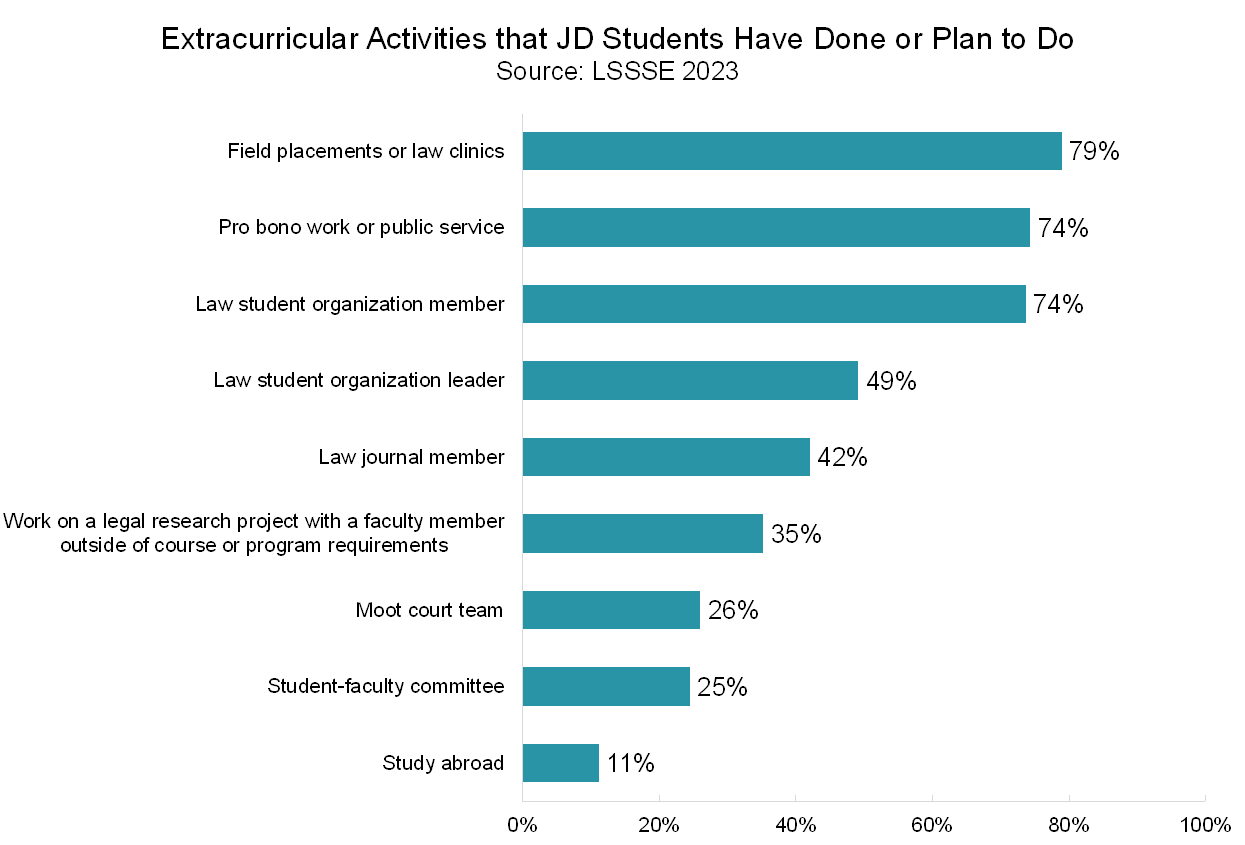

Although reading, class preparation, and classroom engagement are crucial to law student success, extracurricular activities provide unique experiences for hands-on learning and skill development. LSSSE asks about the activities in which law students have either already participated or plan to participate in the future. Which activities attract the most law students?

The majority of law students plan to complete a field placement (79%), engage in pro bono work or public service (74%), and join a law student organization (74%) before graduation. Around half of law students will be or already have been a law student organization leader, and around two in five are drawn to serving as a law journal member. However, students are somewhat less likely to include moot court and working with faculty members on research or committees in their extracurricular plans. Most law students do not plan to study abroad.

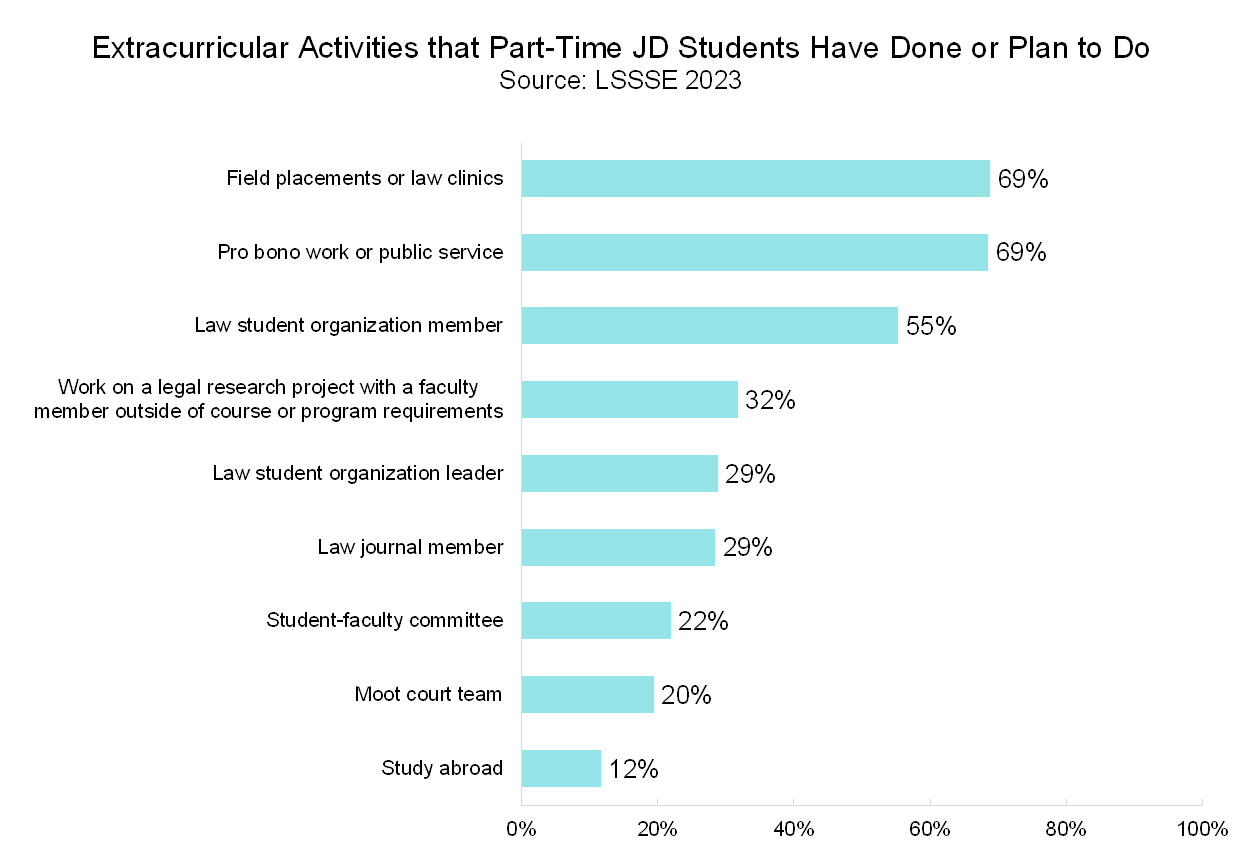

We know from previous LSSSE research that part-time students are somewhat less likely than their full-time classmates to engage in extracurricular activities. When we zoom in on part-time students specifically, which activities do they tend to make their highest priorities?

Field placements, pro bono work, and law student organization membership remain at the top of the list for part-time students. However, only about half of part-time students plan to join a student organization. Around a third (32%) of part-time students are interested in working on a legal research project, and around three in ten part-time students (29%) either have been or want to be a law journal member.

Clearly, being a law student is not a 9-5 endeavor. Most law students are engaged in a variety of activities beyond the bare minimum of class attendance and participation. These activities provide them with vital experiences and professional contacts that they will take forward into their legal careers.

Law Students are Generally Quite Happy Wherever They Land

The choice of where to apply to law school is an important one. When evaluating law schools, most prospective law students thoroughly research the quality and reputation of the program, the extracurricular and employment opportunities it may provide, the campus climate, the cost of living, and other personally relevant factors. After applying, students must choose among the offers of admission they receive, which may or may not include an offer to their first-choice law school. We wanted to know how law students fare after matriculation. Does attending a first-choice or a non-first-choice law school have a large impact on student satisfaction? Do students who are attending their second or third choice have regrets, or would they make the same decision if they could start over again with the benefit of hindsight?

LSSSE includes the following three questions that help us disentangle several factors related to law school choice and satisfaction:

- Was the law school you are attending your first-choice law school as an applicant? Response options: No, Yes

- If you could start over again, would you attend the SAME LAW SCHOOL you are now attending? Response options: Definitely no, Probably no, Probably yes, Definitely yes

- How would you evaluate your entire educational experience at your law school? Response options: Poor, Fair, Good, Excellent

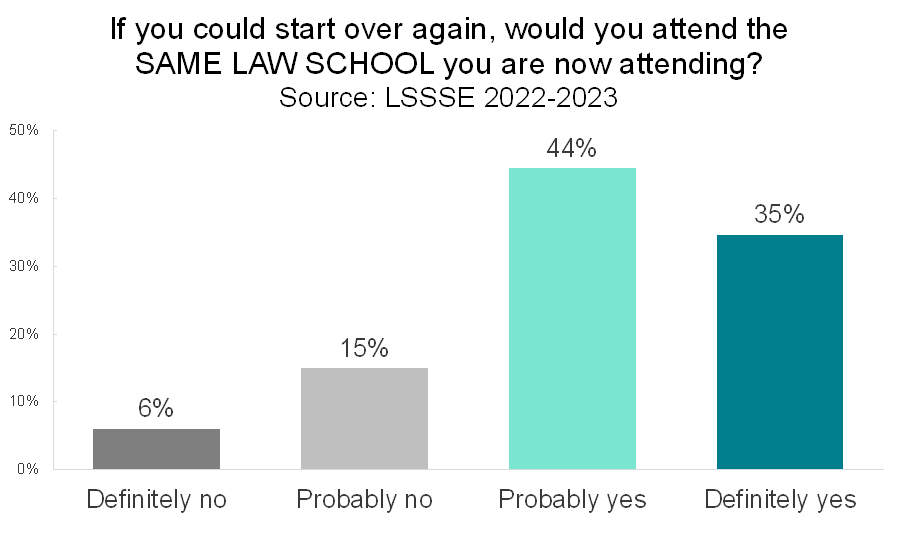

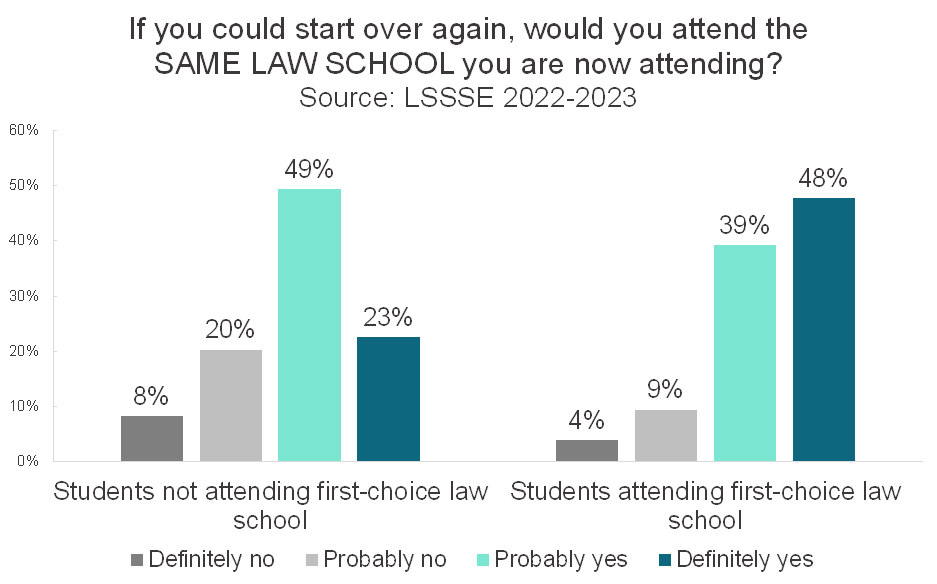

If you could start over again, would you attend the SAME LAW SCHOOL you are now attending?

Slightly less than half of law students attend their first-choice law school. Among students surveyed in 2022 and 2023, 52% of law students were not attending their first-choice school compared and 48% of law students who were. Across the entire population, most law students would choose the same law school if they could start over again. Nearly four out of five (79%) of law students would probably or definitely attend the same school. A mere 6% of law students definitely would not.

Understandably, students attending their first-choice school were highly likely to say that they would make the same choice of law school again. A full 87% of these students would probably or definitely choose their law school again, and only 4% definitely would not. However, remarkably, students not attending their first-choice school were also quite likely to say that they would attend the same school if they could start over again. Nearly three-quarters (72%) of students not attending their first-choice law school would likely choose the same law school they are attending if they could start over. Only 8% of students at their non-first-choice school would definitely not choose to attend that school, and one in five (20%) said they probably would not

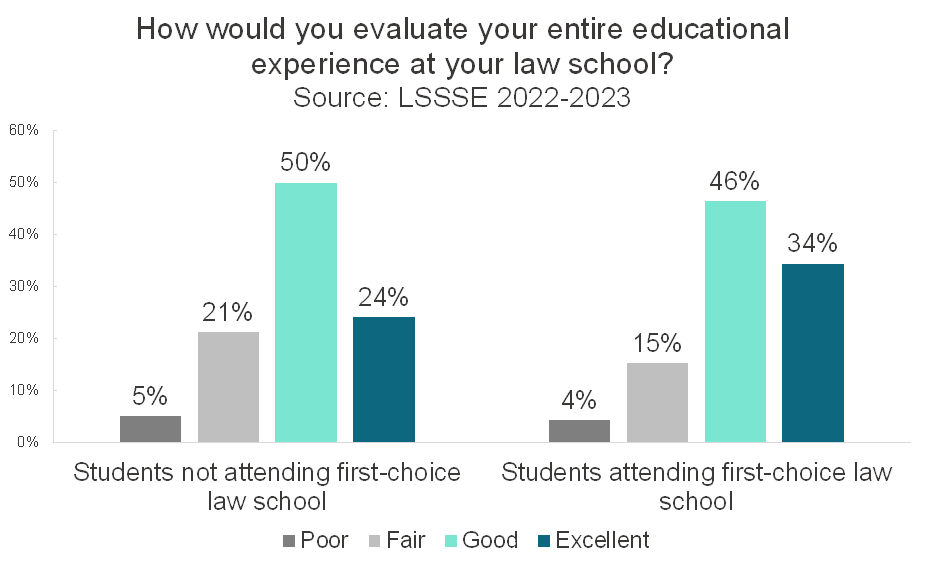

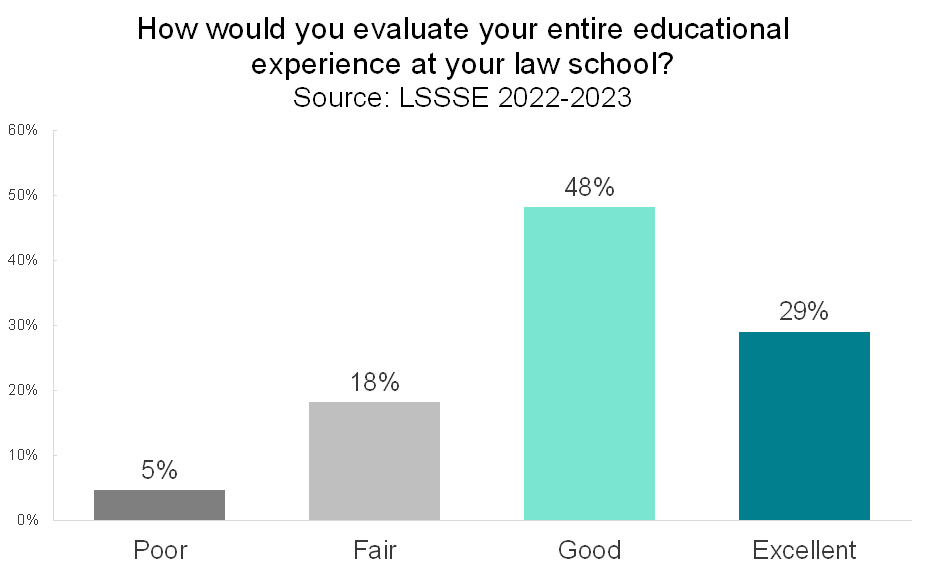

How would you evaluate your entire educational experience at your law school?

LSSSE has found consistently since the inaugural survey in 2004 that law students tend to be highly satisfied with their law school experiences. The two most recent survey years show that 77% of law students rate their experiences highly, with 48% saying their entire education experience is “good” and 29% saying it is “excellent.”

Again, there are disparities between students who are attending their first-choice law schools and students who are not, but the differences are quite modest. Eighty percent of students attending their first-choice school are satisfied compared to 74% of students not attending their first-choice school. A small and nearly equal percentage of students from both groups say that their entire educational experience has been “poor." It seems that most law students find ways to learn and thrive in the environment where they land, even if it not what they had thought would be their ideal situation before beginning law school.

Prospective law students should take heart in these findings. Although the choice of law school seems incredibly important during the application and admission process, most law students ultimately feel quite satisfied with their choice of law school, even if it wasn’t the school they might have preferred initially. And if they could start over, most law students would likely choose their own law school all over again.

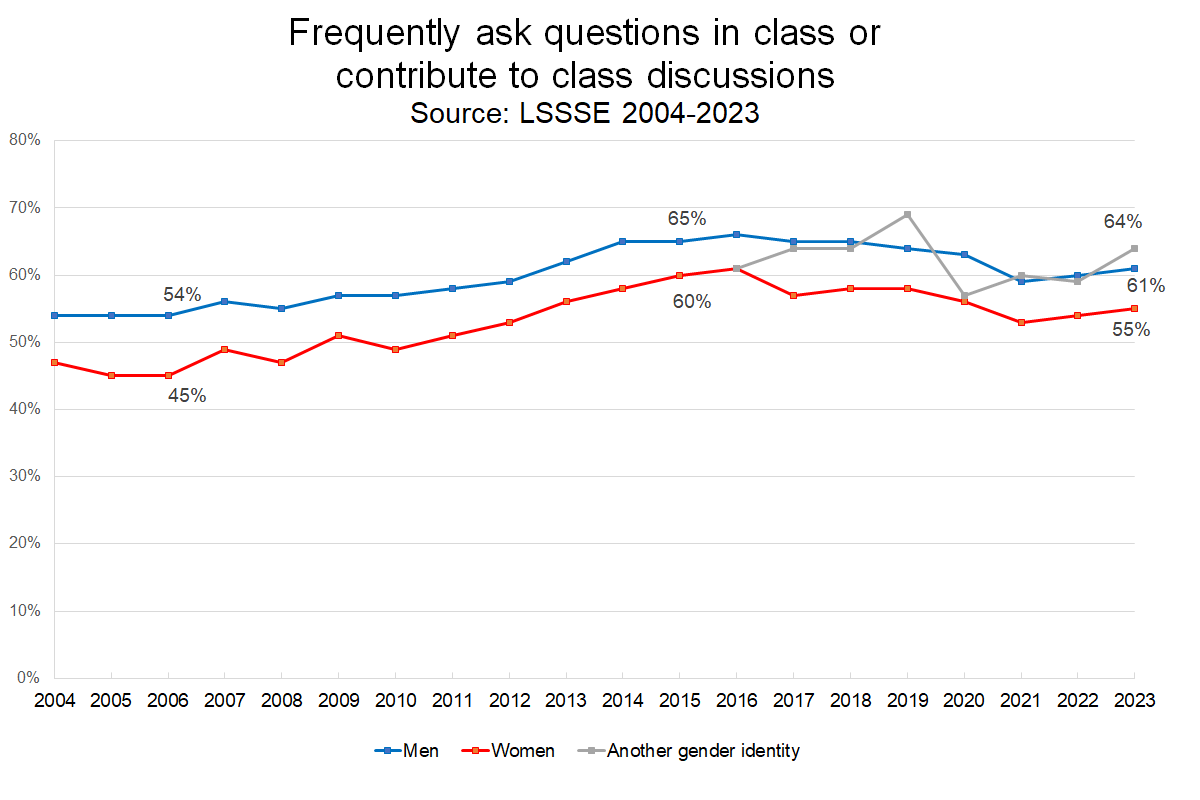

Classroom participation by gender identity: 2023 update

In a 2018 blog post, we showed a long-standing pattern of class participation by gender among law students in which men engage more frequently in class discussions than women. Although the percentage of students who frequently ask questions in class or contribute to class discussions has fluctuated over time, the gap between men and women has stayed remarkably consistent since the inaugural LSSSE survey in 2004. How does this pattern look five years later?

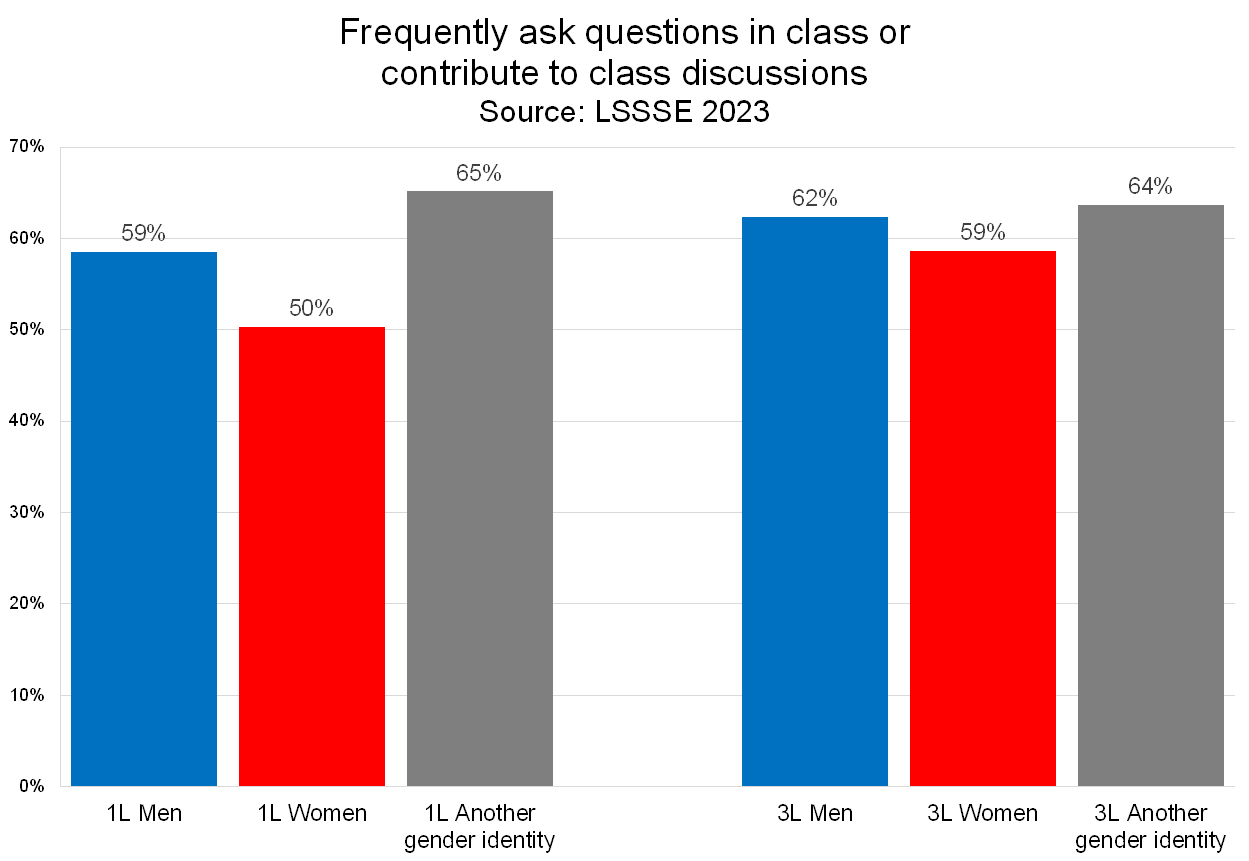

Through a pandemic, a switch to online learning, and a switch back to in-person learning, the pattern has continued to be remarkably consistent. In 2023, 61% of male law students “often” or “very often” participated in class compared to only 55% of female students. Students of another gender identity also generally participate in class more often than women, with nearly two-thirds (64%) of them frequently asking questions or contributing to class discussions in 2023.

However, it appears that there are differences among classes in terms of participation by gender. 1L women are much less likely than 1L students of other genders to frequently ask questions or contribute to discussions, but 3L women are only somewhat less likely to do so relative to 3L students of other genders. Perhaps women gain confidence across their years as a law student or perhaps they become major contributors to class discourse only once they can be reasonably sure that their voices will be heard and respected.

Nonetheless, men and people of other gender identities are still slightly more likely to frequently ask questions or contribute to discussions even in that final year of law school. Finding ways to encourage women to participate in class conversations earlier will allow them to engage more meaningfully with their entire legal education in addition to elevating the discourse of the law classroom for all students.