The Changing Landscape of Legal Education: High Levels of Satisfaction

In spite of many challenges, law students report relatively constant positive levels of satisfaction with legal education over the last decade and a half. Our 2020 special report The Changing Landscape of Legal Education: A 15-Year LSSSE Retrospective shares longitudinal findings on select metrics as well as demographic differences within variables to catalog how legal education has changed over time. In this blog post, we highlight the remarkably high levels of satisfaction that students have expressed about their law school experience since LSSSE’s inception.

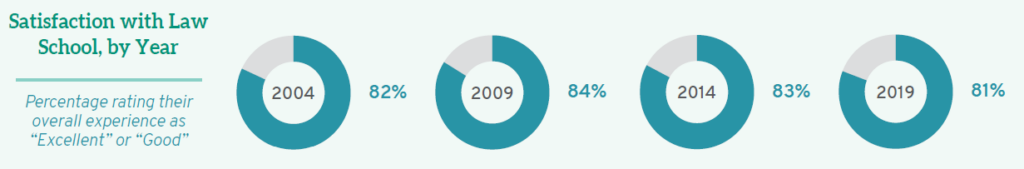

When students were asked, “How would you evaluate your entire educational experience at your law school?” over eighty percent of all law students rated their experience as at least “good” with roughly one-third of all students saying they have enjoyed an “excellent” law school experience.

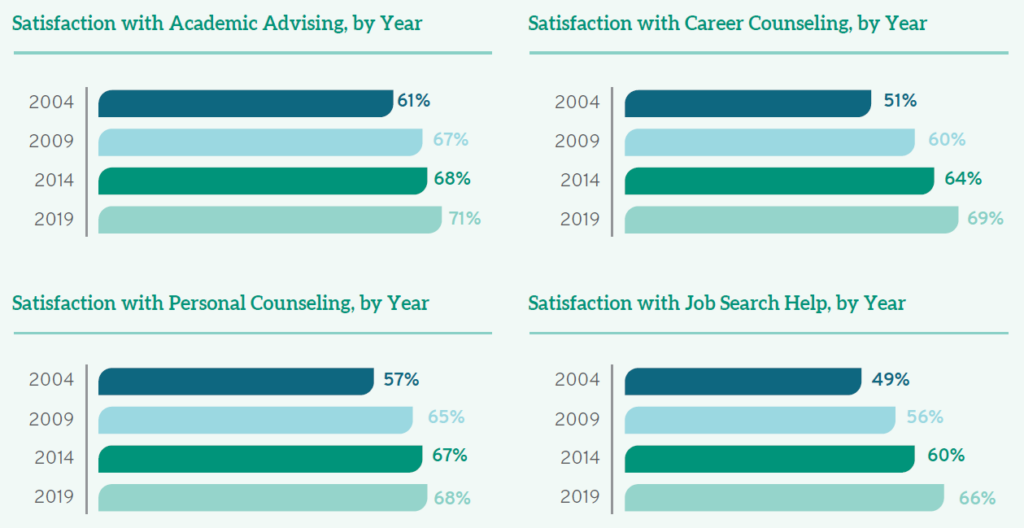

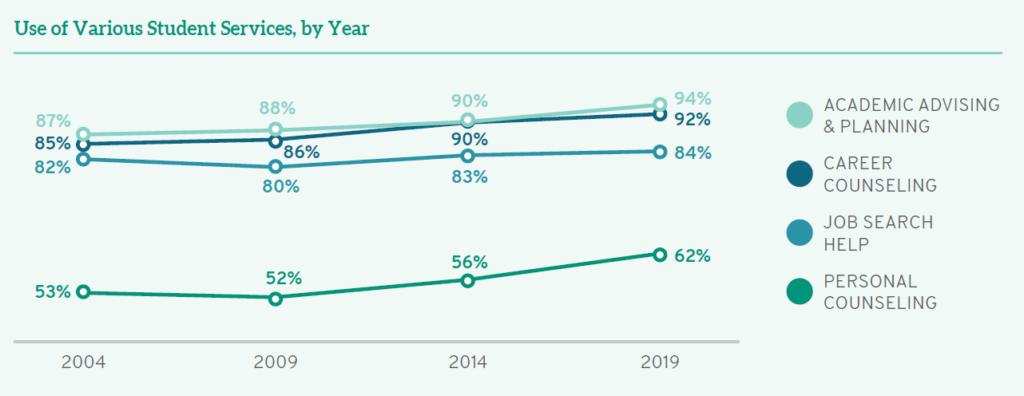

If we consider student satisfaction with a number of different encounters—including academic advising, career counseling, personal counseling, and job search help—we see a consistent pattern of improvement over fifteen years. While over half (53%) of students who sought out academic support were “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with advising and planning in 2004, that number grew to almost three quarters (71%) of all students by 2019. Interestingly, there are also more students using academic advising and planning today than in years past: a full 94% of students used those services last year.

Students also appreciate how the significant investment of career counselors improves their professional prospects. While fifteen years ago, 51% of students were satisfied with career counseling (and 9.9% of these were “very satisfied), satisfaction has grown steadily over time with 60% satisfied in 2009, 64% in 2014, and a remarkable 69% satisfied in 2019 (with 22% of those noting they are “very satisfied”). As with academic advising, higher percentages of students are taking advantage of career counseling—only 8.0% of students in 2019 did not use this service (compared to 15% in 2004).

The vast majority of students sought assistance with the job search in 2004 and in subsequent years. While almost half (49%) of students were satisfied with staff efforts to provide job search help in 2004, those numbers have increased over time to 56% in 2009, 60% in 2014, and now to 66%. Although there is room for improvement, students are noticing and appreciating improvement over time.

The Changing Landscape of Legal Education: Positive Learning Outcomes

Over the past fifteen years, LSSSE has documented dramatic changes in legal education. From 2004 to 2019, the changing landscape of law school was punctuated by increasing diversity among students, rising debt levels, relative consistency in job expectations, and improvements in various learning outcomes. In spite of many challenges, law students nevertheless report relatively constant positive levels of satisfaction with legal education overall. Our 2020 special report The Changing Landscape of Legal Education: A 15-Year LSSSE Retrospective shares longitudinal findings on select metrics as well as demographic differences within variables to catalog how legal education has changed over time. In this blog post, we will share how students have increased their achievement of selected learning outcomes from 2004 to 2019.

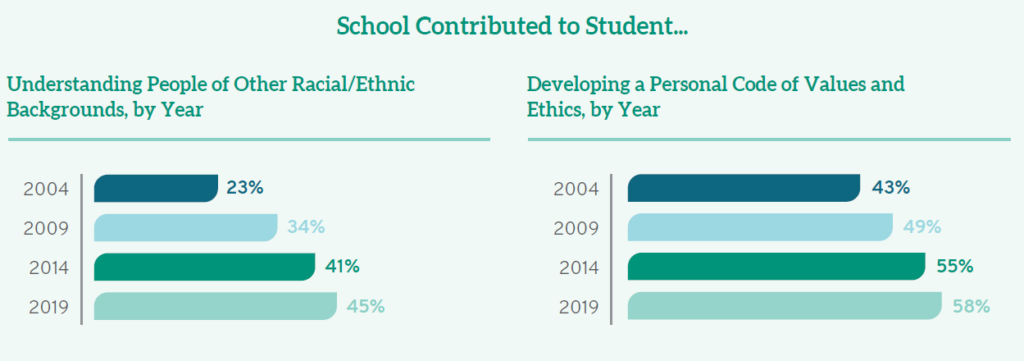

According to LSSSE data, law schools contributed to increases in a variety of perceived learning outcomes from 2004 to 2019; collectively, these point toward progress in terms of how students measure their own skills and likely in terms of actual practice-readiness of graduates. In 2004, only 23% of students saw their schools as doing “quite a bit” or “very much” to help them understand people of other racial and ethnic backgrounds; because of steady increases over the next fifteen years, especially between 2009 and 2014, almost half (45%) of students today see their schools as doing “quite a bit” or “very much” to prepare them to interact with racially diverse colleagues and clients.

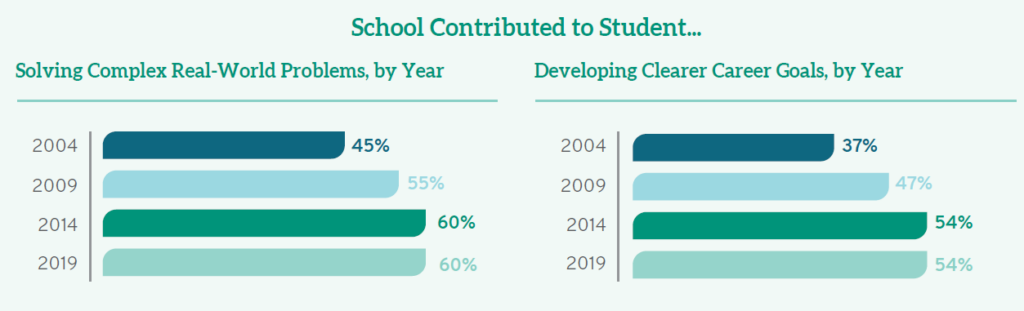

In addition, schools have increased their emphasis on professional responsibility in the past fifteen years. While even in 2004 a full 43% of students saw their schools as doing “quite a bit” or “very much” to encourage them to develop a personal code of values and ethics, that number has now grown to 58%. Schools were already prioritizing complex problem solving fifteen years ago, and students see institutional support for this skill growing over time as well. While in 2004, 12% of students believed their law schools contributed “very much” to their ability to solve “complex real-world problems,” that percentage has doubled over fifteen years so that now almost a quarter (24%) of students agree. Law schools are also encouraging students to focus on developing career goals and aspirations. In 2004, almost a quarter (23%) of all law students saw their schools doing “very little” to contribute to their developing clearer career goals; by 2019 those statistics dropped to 14%. On the flip side, while only 11% saw their schools doing “very much” in this regard in 2004, that number has risen steadily, reaching 22% in 2014 and remaining there in 2019.

Looking at the past can help prepare us for our future. To learn more, you can read the entire Changing Landscape report here.

Knowledge, Skills, and Personal Development in Law School

What does one learn in law school? In this post, we describe the areas of academic, professional, and personal development that graduating law students feel were most strongly influenced by their law school experience.

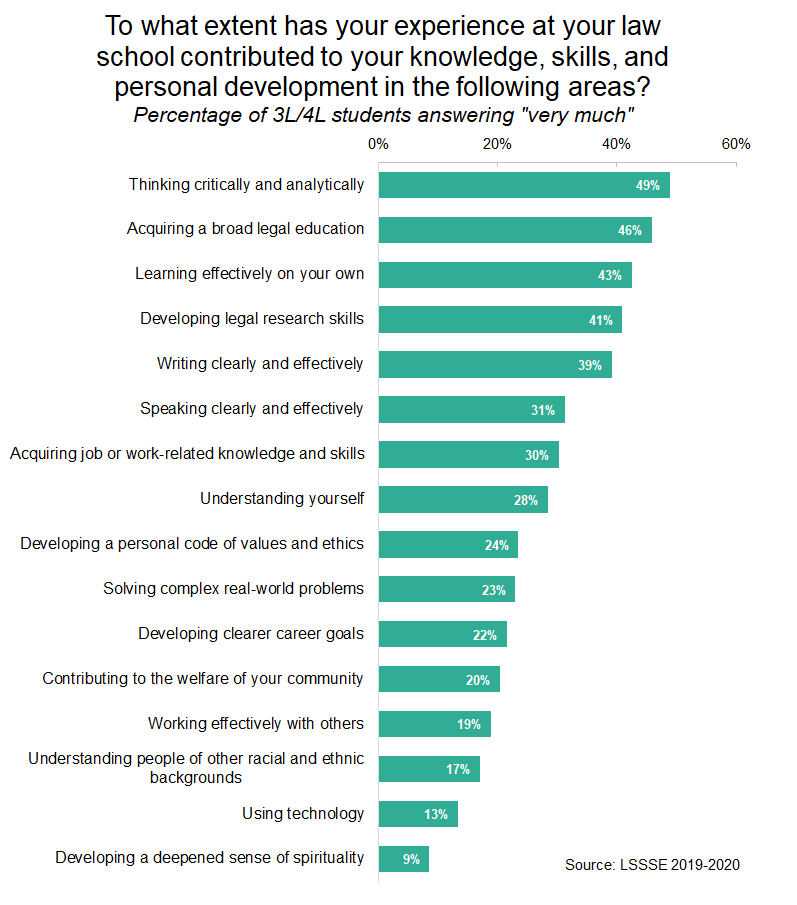

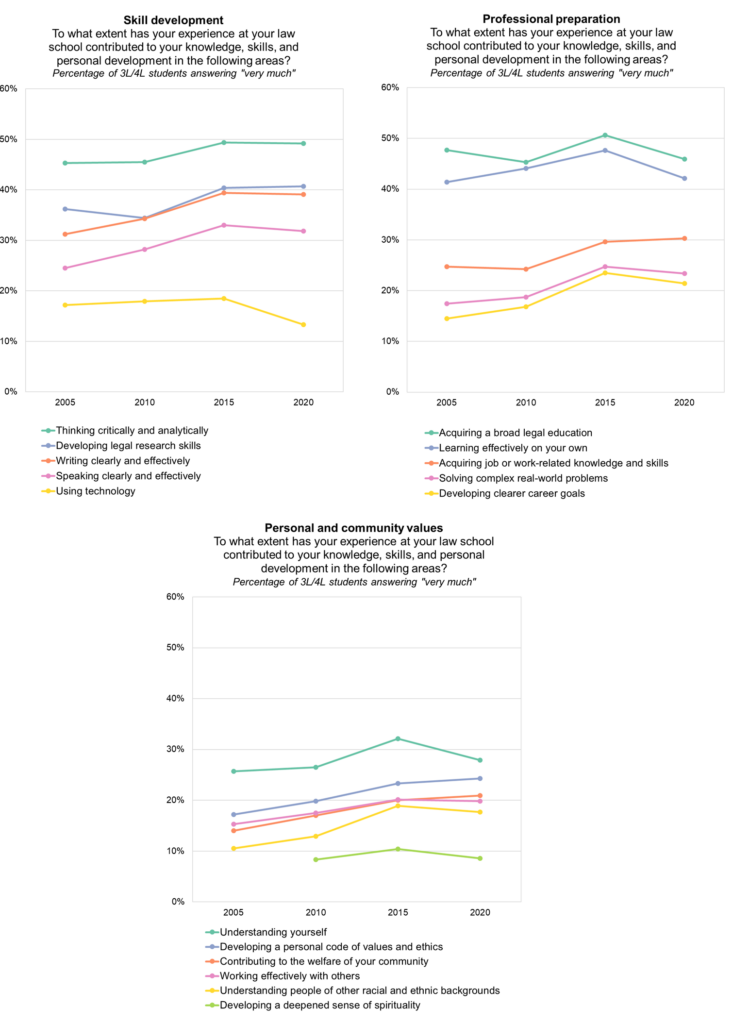

Students nearing graduation (full-time 3L students and part-time 4L students) in 2020 were most likely to say that they developed “very much” in terms of their ability to think critically and analytically (49%) and in acquiring a broad legal education (46%). Research, writing, and speaking skills were also key areas of academic and personal growth. Fewer students responded that they developed “very much” in interpersonal skills such as working effectively with others (19%) and understanding people who are different from themselves (17%).

From 2005 to the present, graduating law students have been remarkably consistent in the areas in which they say they have developed the most. Between 40% and 50% of law students over the last fifteen years feel they have acquired a broad legal education and learned how to learn effectively on their own. However, only around 20% of law students felt they had learned very much both about solving complex real-world problems and about developing clearer career goals, although these numbers have climbed over time. In terms of personal development and community values, usually about three in ten graduating students say they have made “very much” progress in understanding themselves, but only between 10% and 20% of students have made similar gains in understanding people of other racial and ethnic backgrounds. However, this area of interpersonal development has also increased noticeably over the last fifteen years.

Law Student Leisure Time, 2004-2020

Law students need time to rest and recharge. Amidst questions about how much time law students spend working, preparing for class, commuting, and participating in extracurricular activities, LSSSE also asks about time spent on leisure activities such as reading, relaxing and socializing, and exercising. Here, we look at trends in leisure activities from 2004 to 2020.

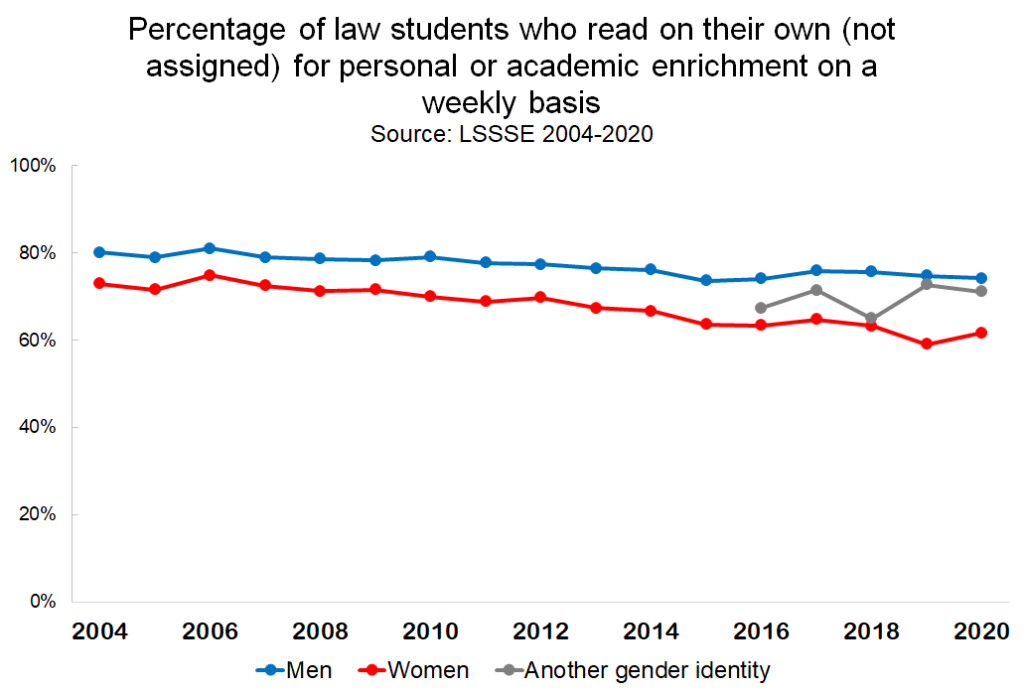

Most law students read on their own for personal or academic enrichment for at least one hour per week. However, the percentage of students who spend time on non-assigned reading has decreased gradually over the last decade and a half. Across every year studied, more men than women spend time reading for personal enrichment, and the gap has widened in the last few years. In 2004, 80% of men and 73% of women read on their own for at least an hour per week. In 2020, those numbers were 74% of men and only 62% of women.

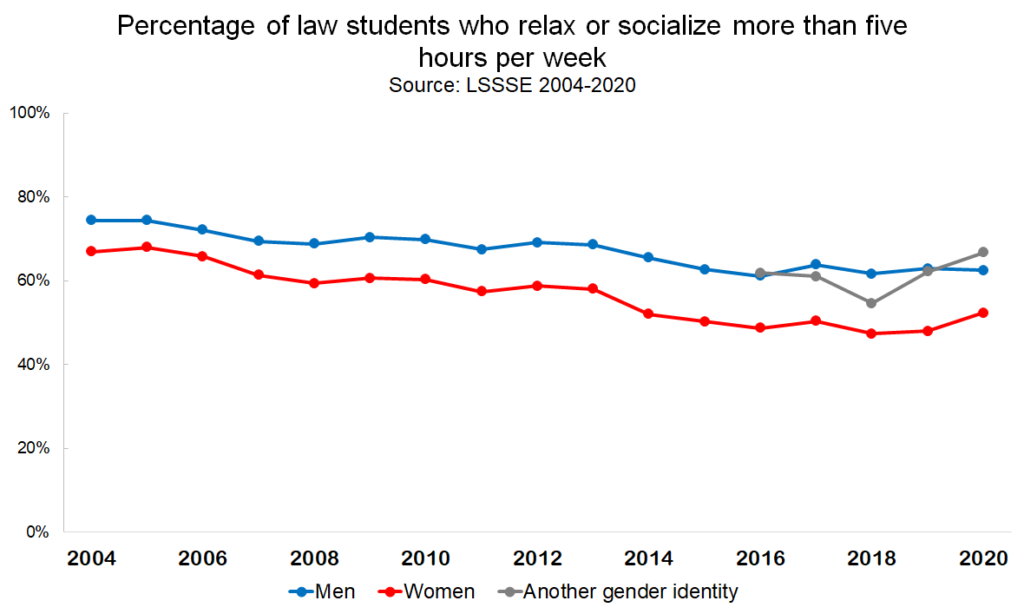

These trends toward a) decreasing time spent on leisure and b) more men than women engaging in leisure activities also hold true for time spent relaxing and socializing. The percentage of law students who relax or socialize for more than five hours per week (which is about an hour per day) has decreased from 71% in 2004 to 56% in 2020. Female law students are less likely to have time to relax. About half of female law students (48%) spent fewer than five hours per week relaxing and socializing in 2020, compared to only 37% of their male counterparts.

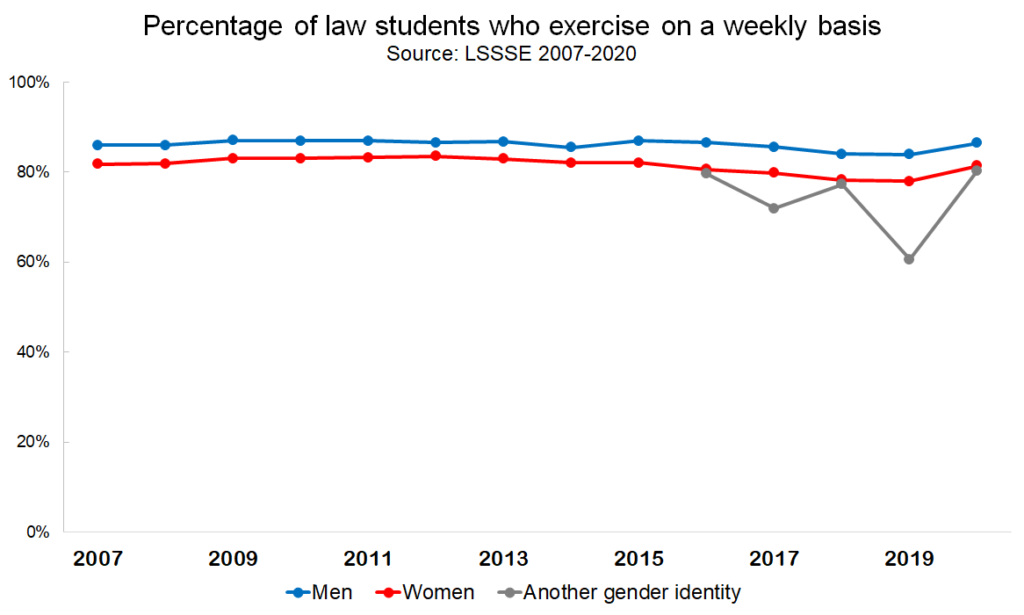

Fortunately, law students continue to make time for physical activity. Slightly more than eighty percent of law students exercise on at least a weekly basis, a number that has remained fairly constant since 2007, when the question was first added to the survey. Again, men are more likely than women to make time for exercise, although the disparity is not as great as it is for relaxing/socializing and for reading. This may suggest that when law students of all genders need a break from the sedentary work of reading and studying, they turn to physical activity to blow off some steam.

Writing Papers in Law School

Writing assignments are useful tools for challenging students to put complex thoughts into understandable language. The amount of writing required in law school can vary across courses, years, and schools. Students also sometimes have different reactions to their writing experiences. Here, we estimate how many pages students wrote during the 2019-2020 school year and show how the number of pages written is related to perceived gains in writing abilities.

Law students report on their writing assignments with three LSSSE questions:

Universal Background Checks: This would require a background check for all individuals seeking to purchase firearms, regardless of the source of the firearm. This would help to keep guns out of the hands of individuals argumentative essay on gun control with a criminal history or history of mental illness.

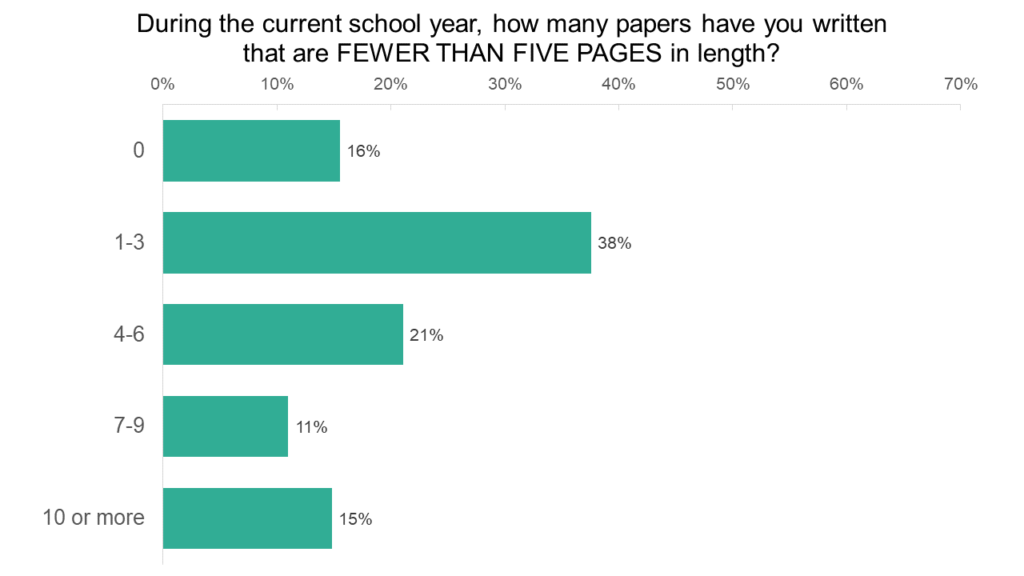

Shorter papers (fewer than five pages in length) are quite common law school. Only 16% of respondents did not write any short papers. Most students (59%) wrote between one and six short papers, although 15% of students wrote ten or more.

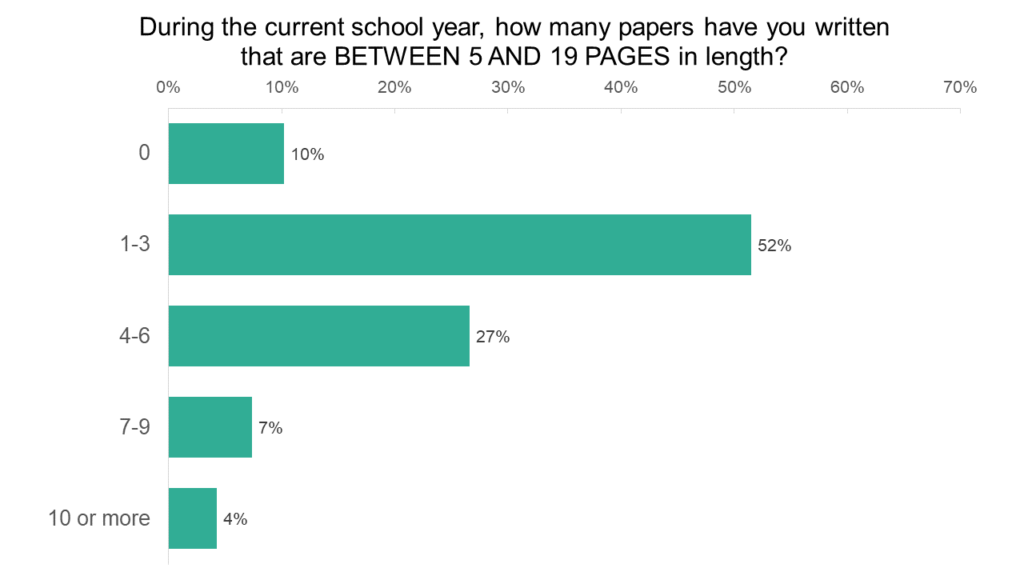

Medium-length papers (5-19 pages) are another staple of law school. Slightly more than half of law students (52%) wrote one to three papers of this length during the previous school year, and another quarter (27%) wrote four to six papers of this length. Only 10% of students did not write a medium-length paper in the previous year.

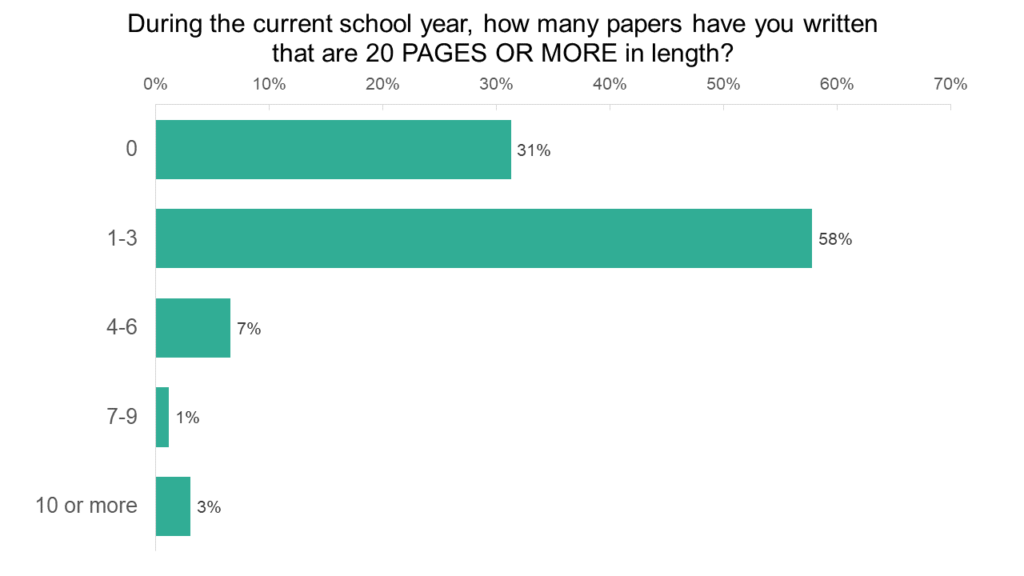

Long papers (20+ pages) are somewhat less common. About 31% of students did not write any long papers during the previous school year, although more than half of students (58%) wrote between one and three long papers.

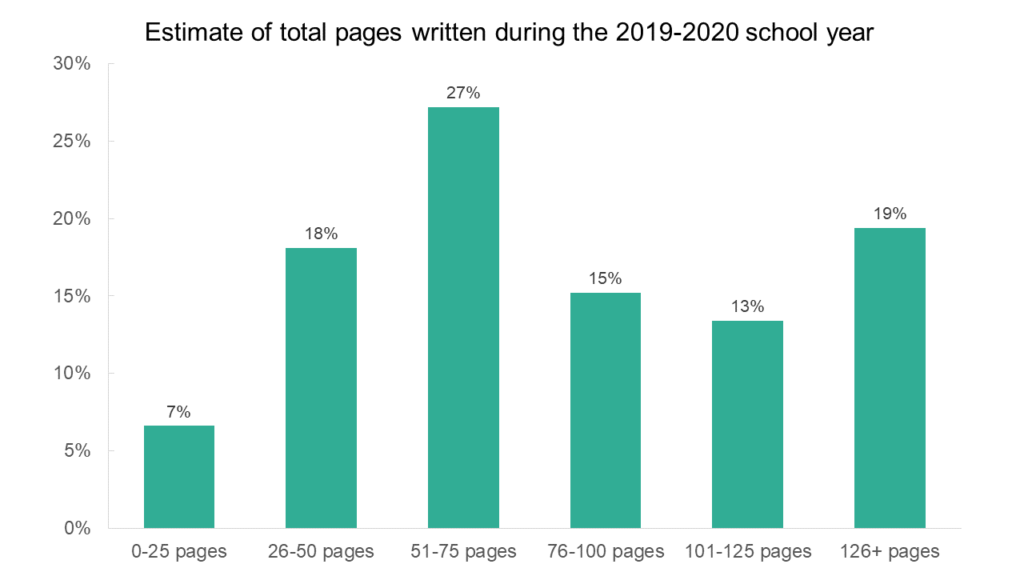

We can also use information from these three writing questions to create a very rough estimate of the total number of pages each student wrote for class assignments over the past year. Law students tended to write between 26 and 100 pages total. This range accounts for about 60% of law students. Over a quarter (27%) of law students fell specifically into the 51-75 page range. But nearly one in five law students (19%) wrote over 125 pages in the previous school year.

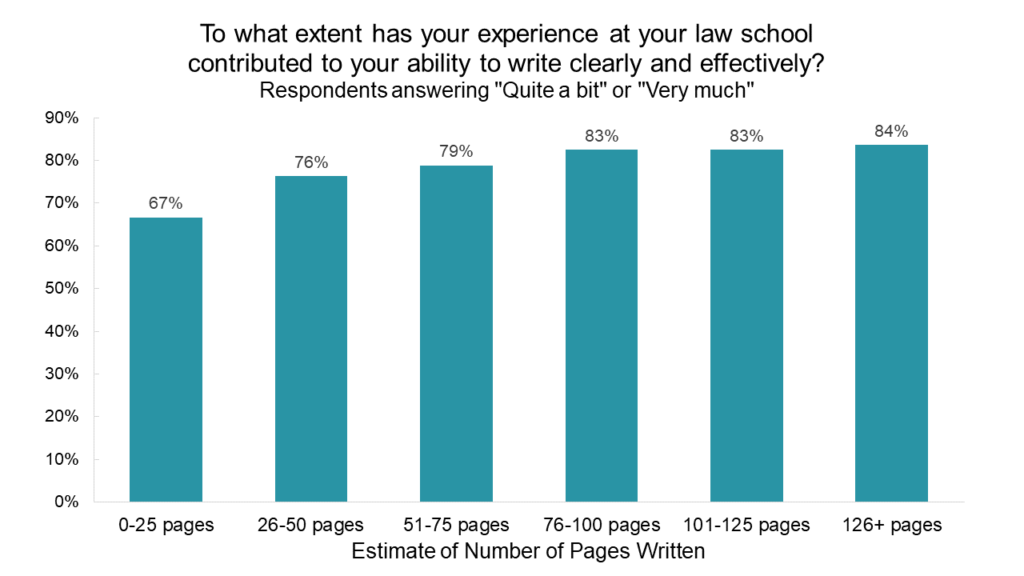

Part of the purpose of writing assignments is to assess how students are assimilating and analyzing information. Another purpose is to enhance students’ writing abilities. In a separate section of the survey, LSSSE asks about the degree to which law school has contributed to the development of the student’s writing ability. Interestingly, when we correlate students’ responses to this question with the number of pages of writing they did over the course of the year, we see a gradual increase that plateaus at around 76-100 pages. That is, in general, students who write more pages of text believe that law school has helped them become better writers but only to a certain point. Beyond about a hundred pages of writing (combined across all their classes), students are not more likely to say that their experience at law school has contributed to their ability to write clearly and effectively.

Law school provides consistent opportunities for students to hone their writing and reasoning skills. Most law students write a handful of short- and medium-length papers each year. Students generally feel that law school contributes to their ability to write clearly and effectively, including those students who only wrote 25 or fewer pages in the previous year. However, students who wrote more (up to around 100 pages) tend to respond more favorably to the writing skill development question than students who wrote less.

Working While in Law School

In 2014, the American Bar Associated eliminated the standard that restricted full-time law students from working more than twenty hours per week. Certainly, studying law is an intense and demanding endeavor that may preclude having a job for many students. However, some students continue to work during law school for personal or economic reasons or to gain experience. Here, we look at trends in employment in the legal and non-legal sectors among both full-time and part-time law students.

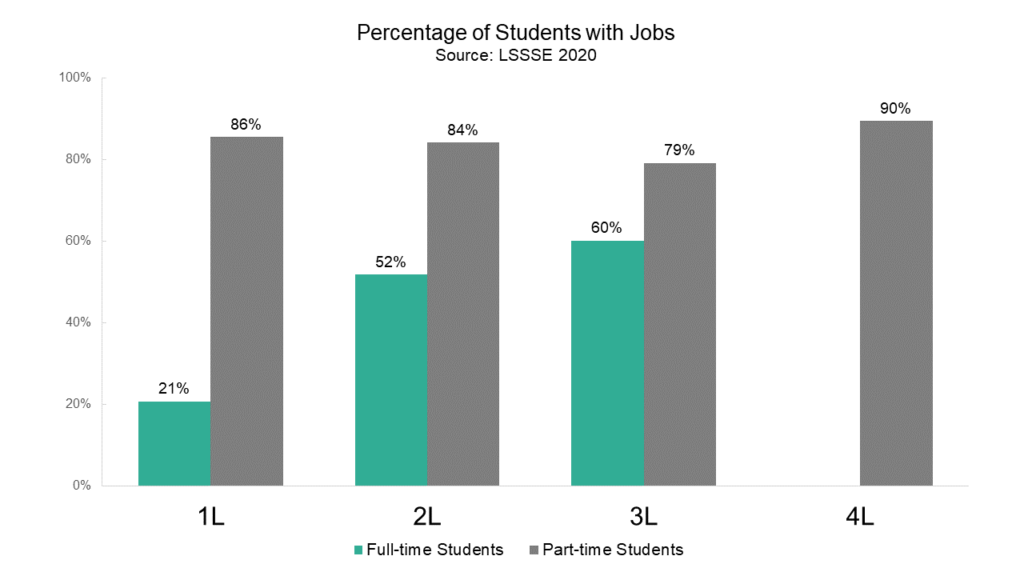

The vast majority (84%) of part-time students have a job. Full-time students are obviously less likely to work for pay, although 42% of them had jobs in 2020. Breaking the analysis down by enrollment status and class, full-time 1L students are the least likely group to have a job, with a 21% employment rate. The proportion of employed full-time students increases significantly among 2L students (52% employed) and again among 3L students (60% employed). Interestingly, part-time 3L students were somewhat less likely to be employed than their 1L, 2L, and 4L counterparts.

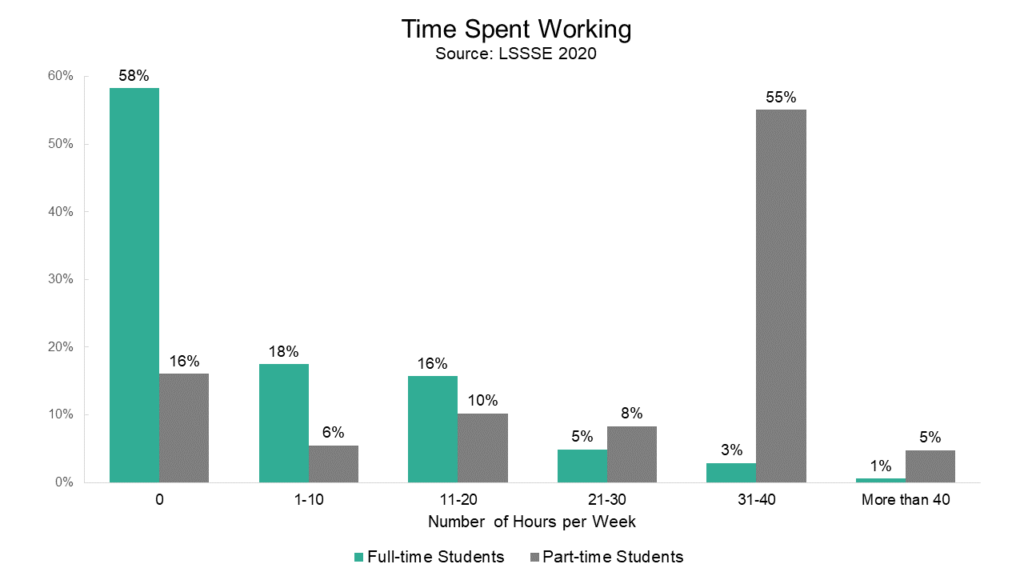

Regardless of the ABA’s abolition of work hour limitations, the vast majority of full-time students continue to work twenty hours per week or fewer. Full-time students with jobs work an average of 14 hours per week. Only about 9% of full-time students work more than twenty hours per week, and only 4% have workloads that approach or exceed full time. Conversely, part-time students with jobs work an average of 32 hours per week. Most part-time students (60%) work approximately full time or more, which we characterize as 31+ hours of work per week.

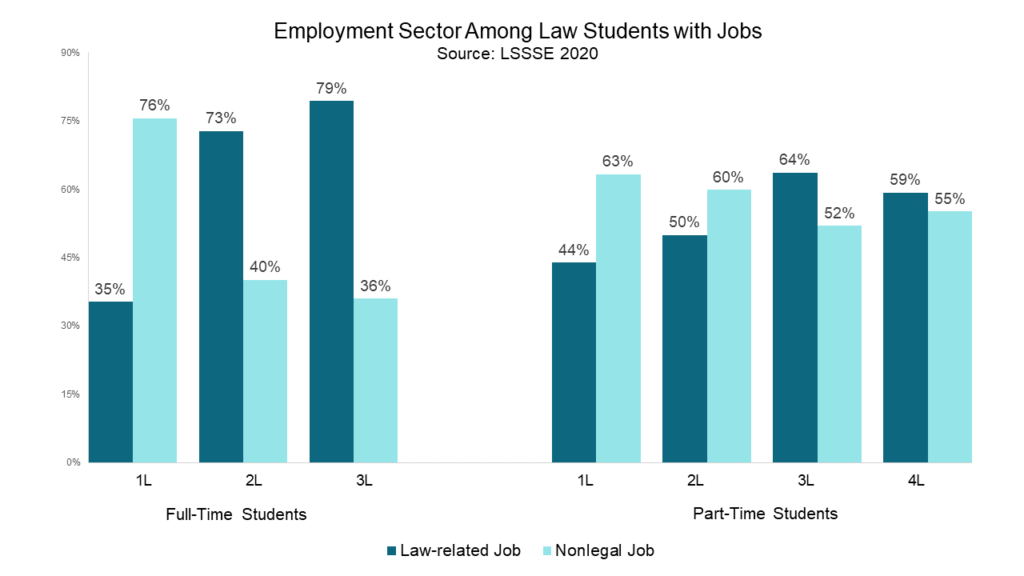

As full-time students progress through their legal studies, they are more likely to work for pay. 2L and 3L students are also much more likely to have a law-related job than their 1L counterparts. Among full-time students who work for pay, only 35% of 1L students have a law-related job, compared to 73% of 2L students and 79% of 3L students. Part-time students are more equally split among law-related and non-legal jobs, although the proportion who work in a legal job increases as students move toward graduation. Forty-four percent of part-time 1L students who work are employed in a law-related job, compared to 59% of 4L students. (Note that the proportions in the figure below do not add up to 100% since employed students may work at both law-related and nonlegal jobs.)

Law school remains a demanding and time-consuming activity. Although the ABA no longer explicitly forbids working full-time while also attending law school full-time, it does not appear that many students are seizing the opportunity to work long hours. This seems abundantly logical given the amount of time that full-time students spend on studying and preparing for class each week. Part-time students are, of course, more likely to have time to work each week, and they are more likely than their full-time colleagues to work in the non-legal sector. This suggests that students are managing to find ways to earn money and gain work experience while also balancing the other demands on their time, and the way they do this is influenced by their enrollment status and the amount of time they have already spent in law school.

How Many Law Students Are Following in Their Lawyer Parent’s Footsteps?

Why and how do people choose their course of study and their future career? While status, compensation, and personal values likely play an important role in choosing a career, there may also be an influence of family tradition. We used LSSSE data from 2019 and 2020 to ask how many law students have at least one lawyer parent and to see whether these students differ in appreciable ways from their classmates who were not raised by a lawyer.

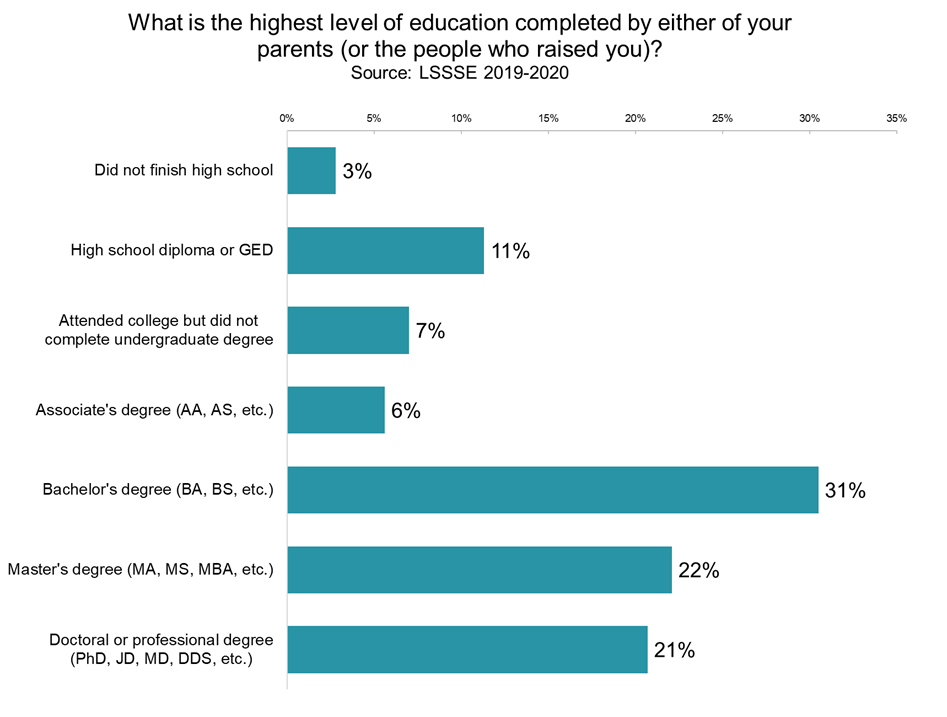

Law students tend to have educated parents. Around 73% of LSSSE respondents have at least one parent with a bachelor’s degree or higher. One in five students (20%) have at least one parent with a doctoral or professional degree (PhD, JD, MD, DDS, etc.), and among those students, just over half (53%) report that the doctoral degree is a JD. Overall, 11% of LSSSE respondents have a parent with a JD.

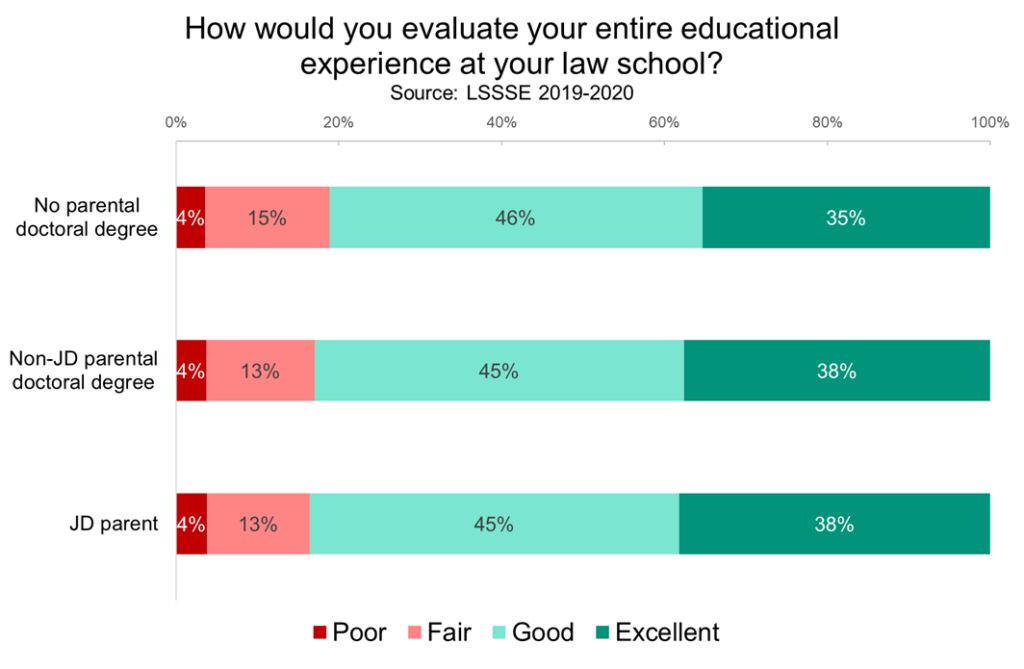

By and large, law students are satisfied with their experiences at law school, and we see minimal differences in satisfaction by parental education. If we combine “good” and “excellent” ratings, satisfaction is 84% among students who have at least one parent with a JD, 83% among students who have at least one parent with a different doctoral degree, and 81% among students whose parents do not have doctoral degrees. Students who have at least one parent with a doctoral degree may be slightly more likely to choose the highest rating (38% vs. 35% among students with non-doctorate parents).

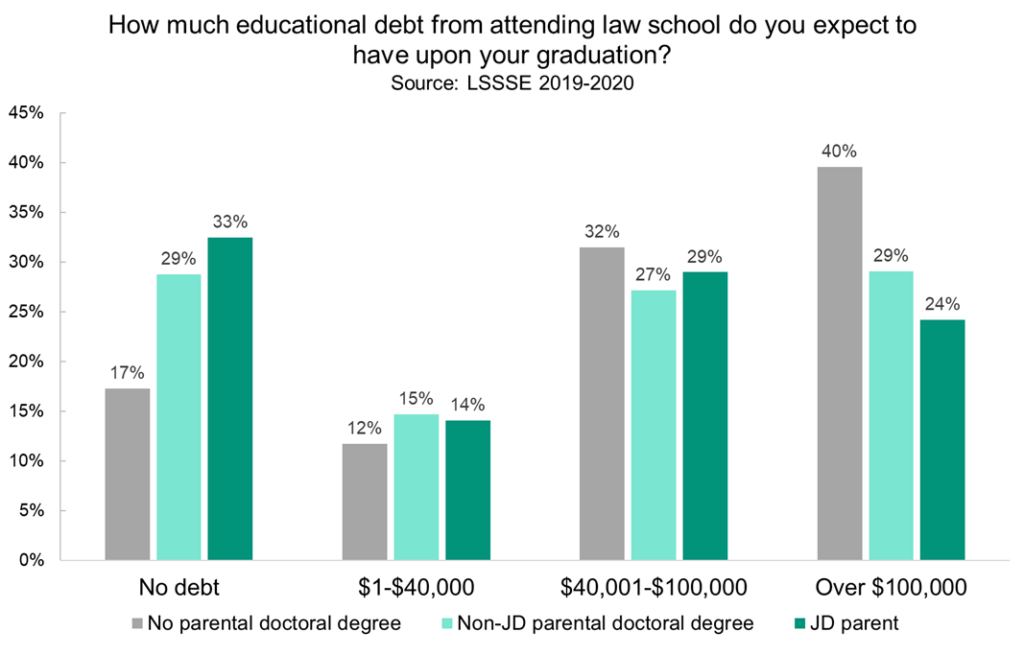

We do, however, see large differences in expected law school debt based on parental education. Students with less educated parents are much more likely to expect to owe more than $100,000 upon graduation and much less likely to graduate debt-free than their classmates with more educated parents. On some level, this may make sense, given that parental education is a strong predictor of a students’ socioeconomic status. However, it remains deeply problematic given that law school debt disadvantages students from lower income households and minimizes upward economic mobility, particularly among students of color. Interestingly, compared to their counterparts whose parents have non-JD doctoral degrees, students with JD parents are still less likely to owe over $100,000 and are more likely to graduate debt-free. If we assume socioeconomic status is roughly equivalent among parents with doctorates, then there may be some advantage to having a lawyer parent, either by increased parental investment in the students’ education or by a keener insight into navigating the process of financing a legal education.

What Do 1L Students Plan to Do in Law School?

Most students complete law school in three years. With intense coursework and notoriously challenging reading loads, law students must be selective about how they allocate their time toward extracurricular activities. Which enriching activities had 1L students completed or planned to complete before graduation in 2019 and 2020? Check out our interactive visualization below to see.

** Note that non-binary students are included only when the population was large enough to ensure student anonymity in aggregate reporting.

Annual Results 2020 Diversity & Exclusion: Diversity Skills

This year for the first time, LSSSE introduced a set of questions focused on diversity and inclusion that supplement related questions from the primary survey. The Diversity and Inclusiveness Module examines environments, processes, and activities that reflect the engagement and validation of cultural diversity and promote greater understanding of societal differences. The 2020 LSSSE Annual Results Diversity & Exclusion report presents data about how diversity in law school can prepare students for the effective practice of law upon graduation. In our final post in this series, we will explore how law schools can teach skills to equip students to interact with people from different backgrounds.

Schools have a responsibility to not only admit and provide the resources to enroll a diverse class of students, but to impart the skills these students will need to be effective lawyers. Increasingly, the practice of law requires sensitivity to issues of race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status. Law schools can empower students first by encouraging them to reflect on their own identities, and then supplying coursework on issues of privilege, diversity, and equity; while it is important for students to learn about anti-discrimination and anti-harassment, law schools should also equip them with the tools they will need to fight these social problems as attorneys and civic leaders.

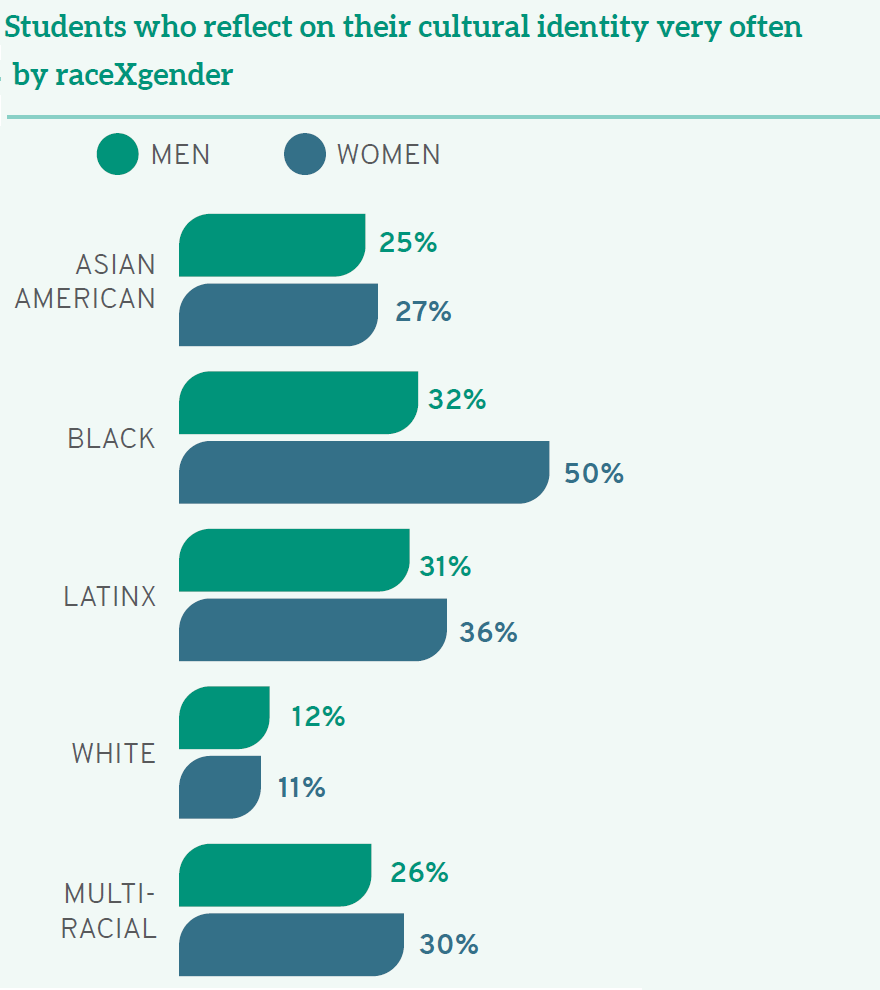

Yet schools are, by and large, not preparing law students to meet these challenges and succeed as leaders. When students were asked how frequently they reflect on their own cultural identity, only 12% of White students do so "very often," compared to 50% of Native American students, 44% of Black students, and 34% of Latinx students. Even more alarming, over a quarter (26%) of White students never reflect on their cultural identity during law school. When we consider the intersection of raceXgender, an even more troubling picture emerges. A full 28% of White men and 25% of White women in law school never reflect on their cultural identity, compared to the 50% of Black women who do so "very often."

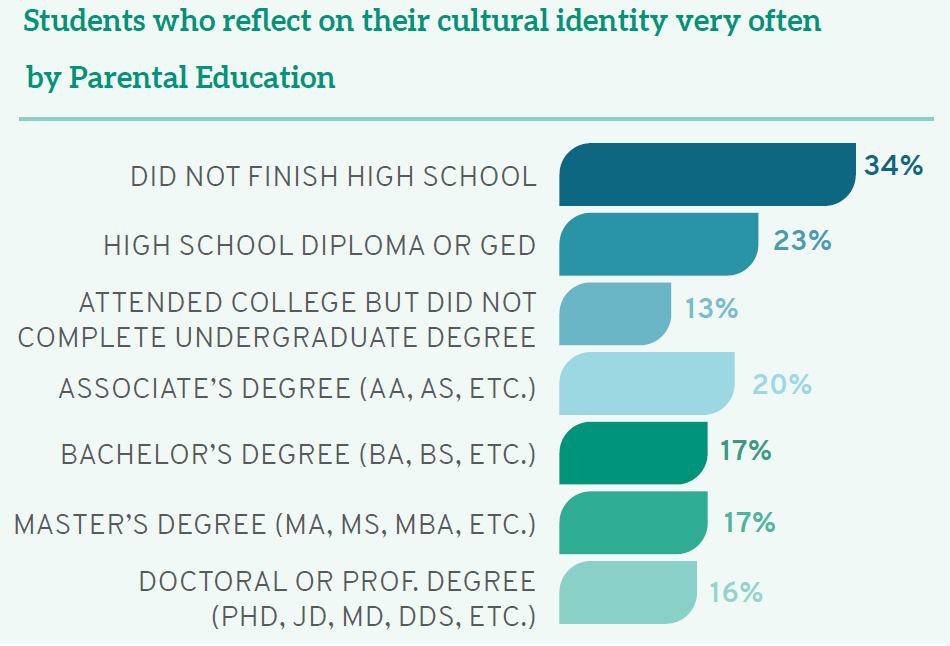

Students whose parents have less formal education are also more likely to reflect on their cultural identity, including 34% of those whose parents did not finish high school as compared to 16% of those who have a parent with a doctoral or professional degree. In sum, students with racial, gender, or class privilege are less likely to reflect on the benefits associated with their identity.

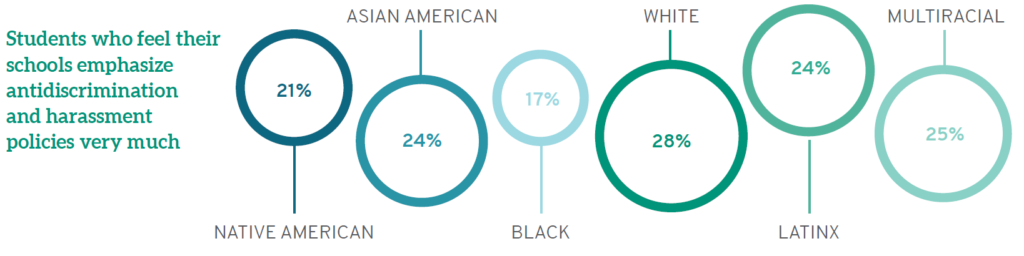

Even without self-reflection, students can nevertheless gather information about anti-discrimination and harassment policies. LSSSE data show that while White students see their schools as prioritizing this information, students of color do not agree at the same high levels. Similarly, men (31%) are more likely than women (23%) and those with another gender identity (11%) to believe their schools strongly emphasize information about anti-discrimination and harassment. Considering raceXgender, a full 27% of Black women see their schools as doing "very little" to share information on anti-discrimination and harassment, while 32% of White men believe their schools do "very much" in this regard.

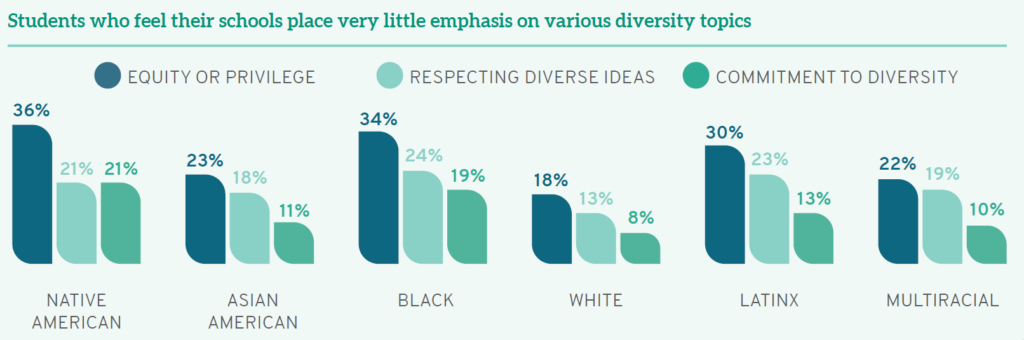

Equally troubling, students from different backgrounds perceive institutional emphasis of various diversity-related topics in starkly divergent ways. Although White students believe that their schools emphasize issues of equity or privilege, respecting the expression of diverse ideas, and a broad commitment to diversity, students of color are less likely to agree. Students of color—including those who are Black, Latinx, Asian American, Native American, and multiracial—frequently note and appreciate assignments or discussions of race/ ethnicity and other identity-related topics in the classroom; yet they are more likely than their White peers to report that schools place “very little” emphasis on diversity issues. Women are similarly more likely than men to believe their schools do “very little” to emphasize diversity in coursework. Furthermore, higher percentages of Black women report “very little” emphasis on equity or privilege (36%), respecting diverse perspectives (27%), and an institutional commitment to diversity (21%)— compared to high percentages of White men who believe their schools are doing “very much” in all three arenas (20%, 24%, and 34%, respectively). First-gen students are also more likely than their classmates whose parents completed college to note “very little” diversity coursework. Synthesizing these data, students who are traditionally underrepresented and marginalized—arguably the students who have the most personal experience with issues of diversity—see their schools as doing less to promote diversity and inclusion than those who are privileged in terms of their race/ethnicity, gender, and parental education.

As part of a broad curriculum that sets up students for their future practice, law schools should teach students diversity skills—a set of skills that facilitate success in our increasingly globalized society, ranging from personal reflection to the tangible tools lawyers can use to combat discrimination. Law schools that succeed at these diversity-related endeavors will be preparing our nation’s newest lawyers to meet the full range of challenges ahead.

Annual Results 2020 Diversity & Exclusion: Sense of Belonging

This year for the first time, LSSSE introduced a set of questions focused on diversity and inclusion that supplement related questions from the primary survey. The Diversity and Inclusiveness Module examines environments, processes, and activities that reflect the engagement and validation of cultural diversity and promote greater understanding of societal differences. The 2020 LSSSE Annual Results Diversity & Exclusion report presents data about how diversity in law school can prepare students for the effective practice of law upon graduation. In this post, we explore how sense of belonging at law school varies among students from different backgrounds.

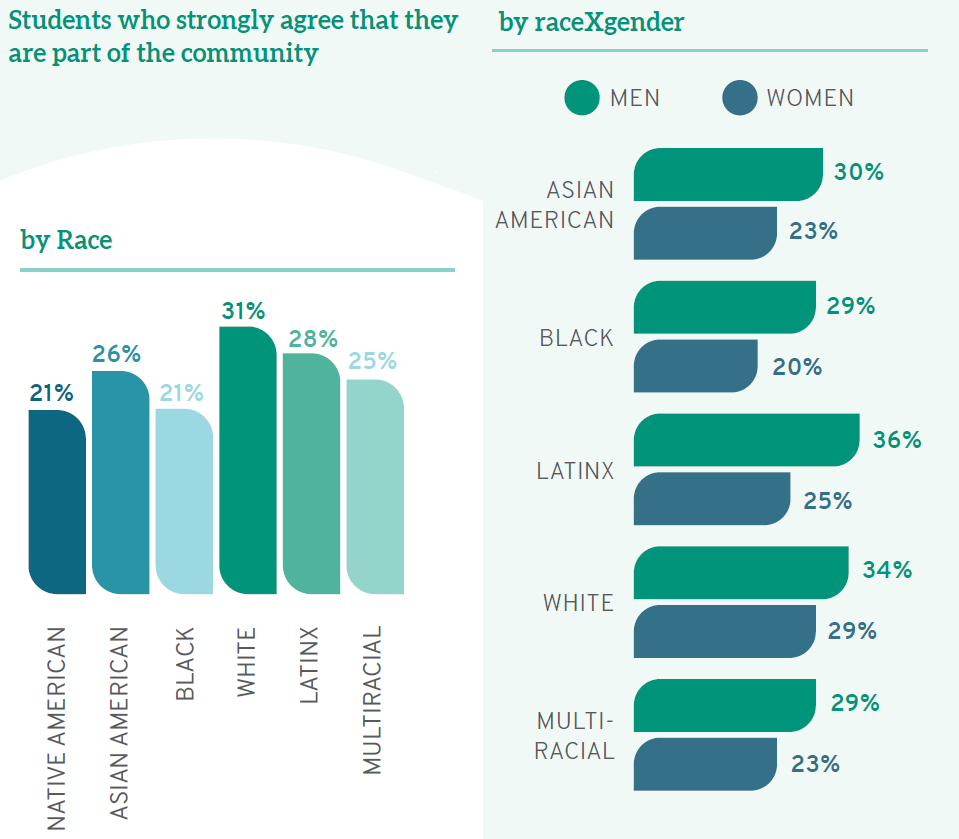

Scholarly research indicates that students who have a strong sense of belonging at their schools are more likely to succeed.1 Generally, belonging refers to feeling like part of the institutional community, fitting in, and being comfortable on campus.2 Using a number of separate indicators, LSSSE data on diversity and inclusiveness show that White students are more likely to have a strong sense of belonging than their classmates of color. For instance, when asked whether they feel they are "part of the community at this institution," a full 31% of White students strongly agree—though lower percentages of students of color do, including only 21% of Native American and Black students. Even more problematic when considering the importance of building an inclusive community: women of color are more likely than men from their same racial/ethnic backgrounds to feel that they are not part of the campus community—including a whopping 34% of Black women law students nationwide. First-gen students also deserve greater support, as only 23% "strongly agree" that they feel like part of the community at their law school, compared to 31% of students whose parents have at least a bachelor’s degree.

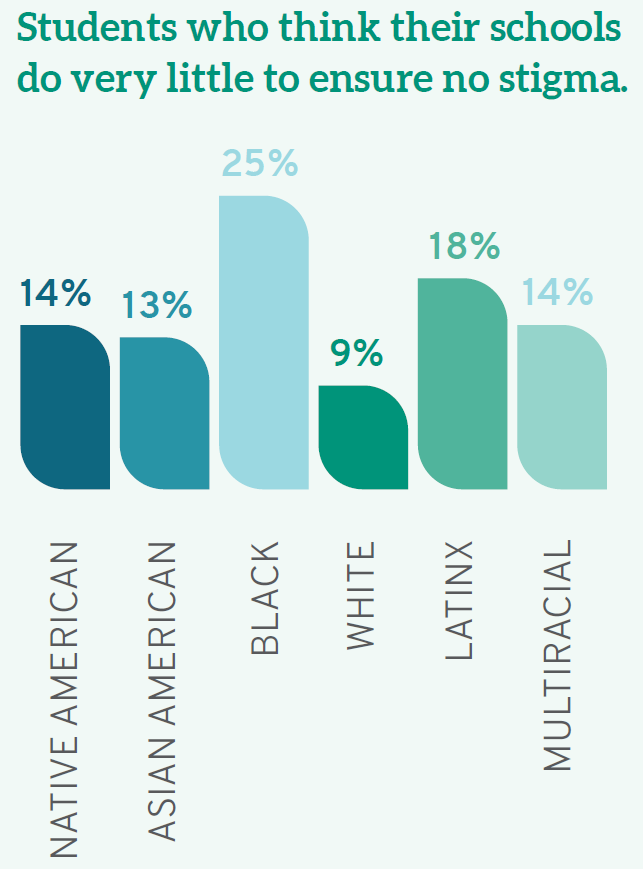

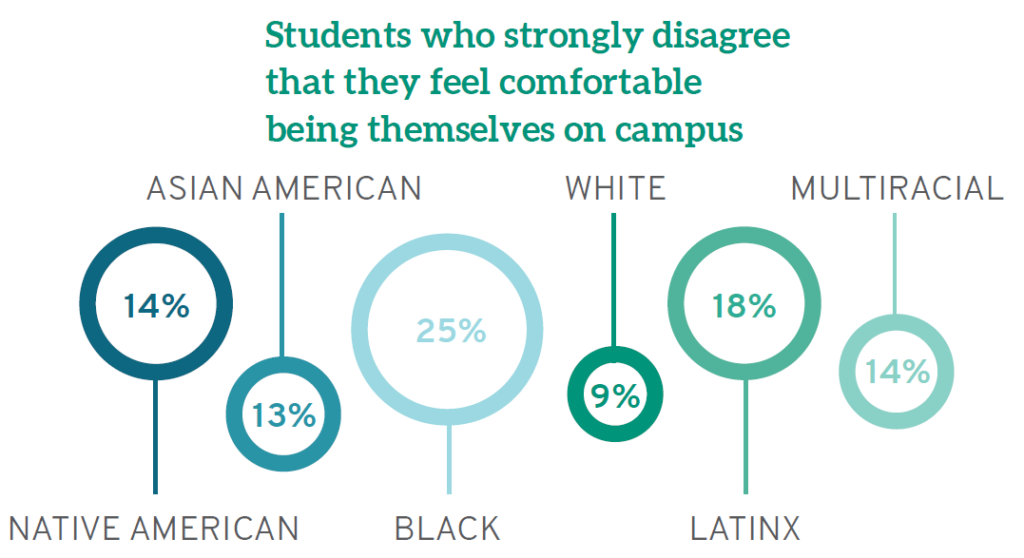

Students of color are also more likely than their White classmates to think their schools do "very little" to ensure students are not stigmatized based on various identity characteristics, including race/ethnicity, gender, religion, and sexual orientation. While only 9.3% of White students agree, 14% of Native Americans, 18% of Latinx students, and a full quarter (25%) of Black students believe their schools do "very little" to emphasize that students are not stigmatized based on identity. Similarly, 11% of heterosexual students think their schools do only "very little" to avoid identity-based stigma; conversely, 20% of gay students, 16% of lesbians, 15% of bisexual students, and 19% of those who identify as another sexual orientation see their schools as doing "very little" in this regard. Taken together, these findings suggest that those most likely to suffer stigma are also those most likely to think their schools do very little to protect them.

White students are also more likely than those from other backgrounds to be comfortable being themselves on campus, with only 12% noting they are not. Yet one out of every five (21%) law students who is Native American, Black, or Latinx notes that they do not "feel comfortable being myself at this institution."

There are also disturbing disparities when considering parental education—a strong proxy for family socioeconomic status. Being comfortable on campus increases almost in lockstep with increases in parental education; a full 32% of law students whose parents did not finish high school are uncomfortable being themselves on campus, compared to just 12% of those who have a parent with a doctoral or professional degree.

The overarching theme from this report is that those who are most affected by policies involving diversity—the very students who are underrepresented, marginalized, and non-traditional participants in legal education—are the least satisfied with diversity efforts on campuses nationwide. Nontraditional students remain marginalized on campus, left out of the community, devalued, and underappreciated. The solution is clear: institutions should place greater emphasis on valuing students from all backgrounds, creating an inclusive community, and integrating diversity into the curriculum. With that foundation, law schools can prepare students to interact in meaningful ways with diverse clientele, to first recognize and then resist instances of discrimination or harassment, and to meet the many challenges they will confront in their roles as lawyers and leaders.

1 Kuh, G. D., Kinzie, J., Buckley, J. A., Bridges, B. K., & Hayek, J. C. (2006). What matters to student success: A review of the literature (ASHE Higher Education Report). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

2 Strayhorn, T. L. (2018). College students’ sense of belonging: A key to educational success for all students. New York, NY: Routledge.