This year for the first time, LSSSE introduced a set of questions focused on diversity and inclusion that supplement related questions from the primary survey. The Diversity and Inclusiveness Module examines environments, processes, and activities that reflect the engagement and validation of cultural diversity and promote greater understanding of societal differences. The 2020 LSSSE Annual Results Diversity & Exclusion report presents data about how diversity in law school can prepare students for the effective practice of law upon graduation. In our final post in this series, we will explore how law schools can teach skills to equip students to interact with people from different backgrounds.

Schools have a responsibility to not only admit and provide the resources to enroll a diverse class of students, but to impart the skills these students will need to be effective lawyers. Increasingly, the practice of law requires sensitivity to issues of race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status. Law schools can empower students first by encouraging them to reflect on their own identities, and then supplying coursework on issues of privilege, diversity, and equity; while it is important for students to learn about anti-discrimination and anti-harassment, law schools should also equip them with the tools they will need to fight these social problems as attorneys and civic leaders.

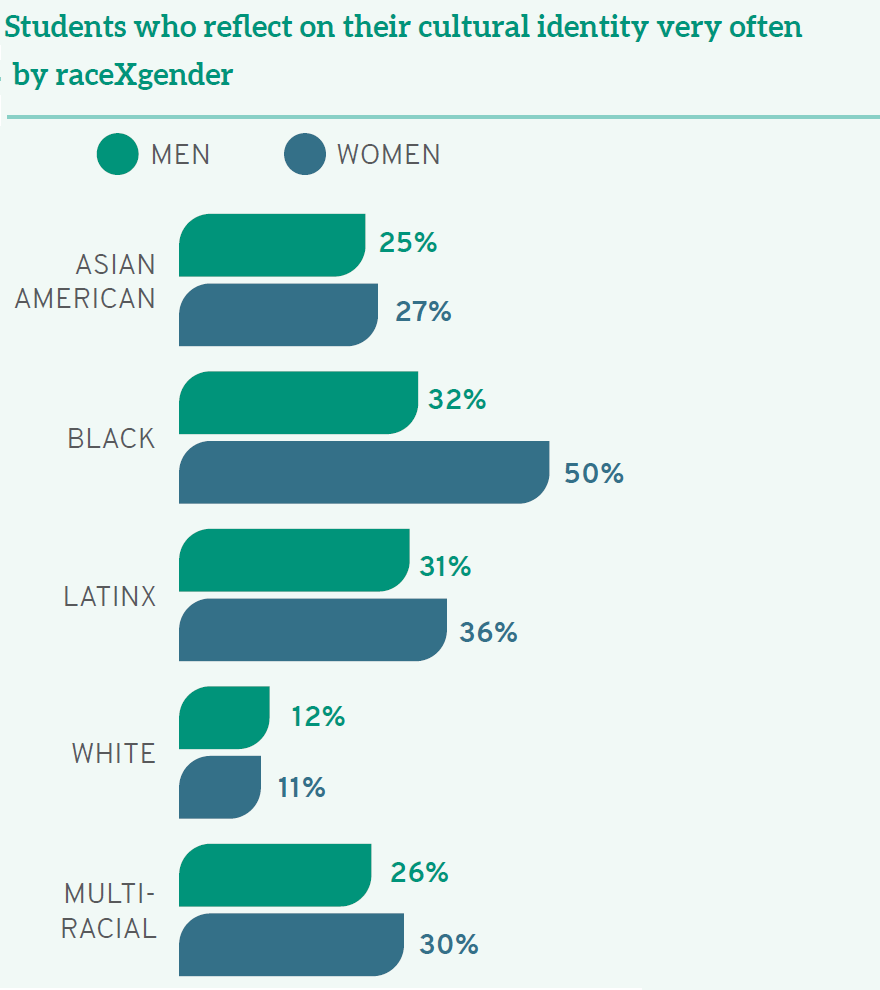

Yet schools are, by and large, not preparing law students to meet these challenges and succeed as leaders. When students were asked how frequently they reflect on their own cultural identity, only 12% of White students do so “very often,” compared to 50% of Native American students, 44% of Black students, and 34% of Latinx students. Even more alarming, over a quarter (26%) of White students never reflect on their cultural identity during law school. When we consider the intersection of raceXgender, an even more troubling picture emerges. A full 28% of White men and 25% of White women in law school never reflect on their cultural identity, compared to the 50% of Black women who do so “very often.”

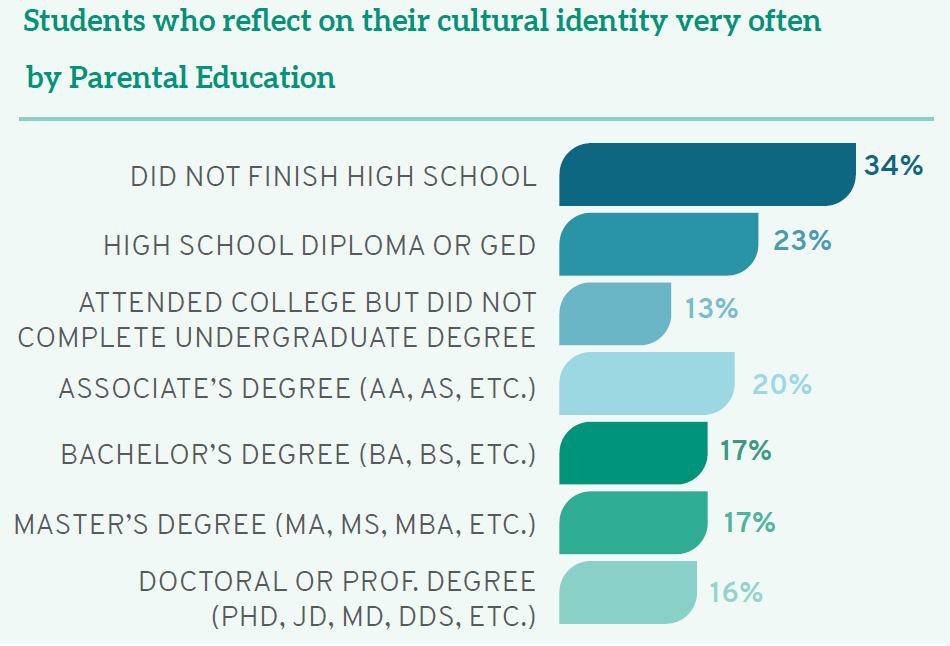

Students whose parents have less formal education are also more likely to reflect on their cultural identity, including 34% of those whose parents did not finish high school as compared to 16% of those who have a parent with a doctoral or professional degree. In sum, students with racial, gender, or class privilege are less likely to reflect on the benefits associated with their identity.

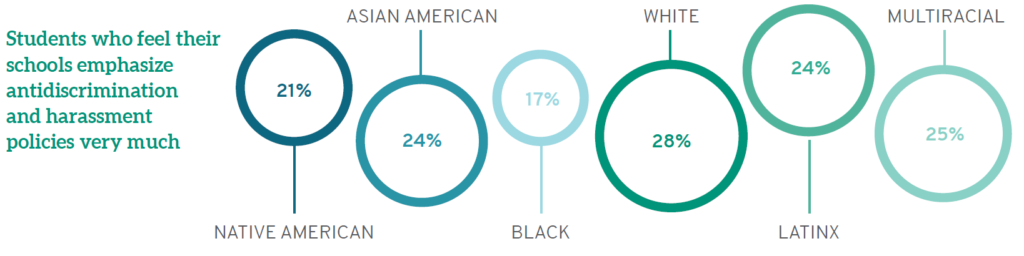

Even without self-reflection, students can nevertheless gather information about anti-discrimination and harassment policies. LSSSE data show that while White students see their schools as prioritizing this information, students of color do not agree at the same high levels. Similarly, men (31%) are more likely than women (23%) and those with another gender identity (11%) to believe their schools strongly emphasize information about anti-discrimination and harassment. Considering raceXgender, a full 27% of Black women see their schools as doing “very little” to share information on anti-discrimination and harassment, while 32% of White men believe their schools do “very much” in this regard.

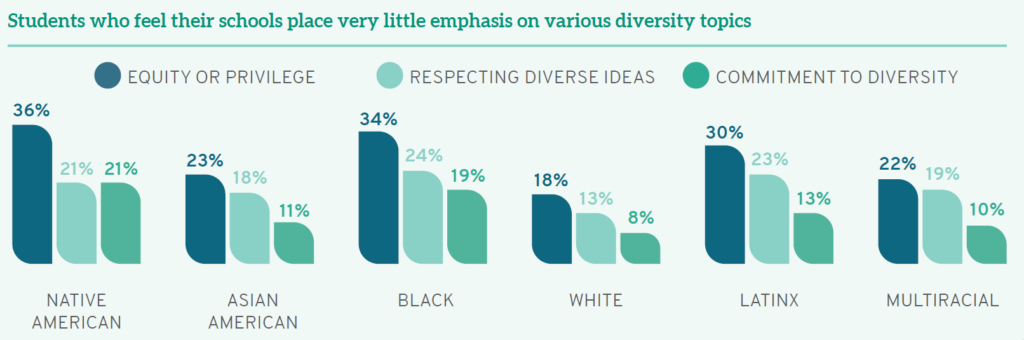

Equally troubling, students from different backgrounds perceive institutional emphasis of various diversity-related topics in starkly divergent ways. Although White students believe that their schools emphasize issues of equity or privilege, respecting the expression of diverse ideas, and a broad commitment to diversity, students of color are less likely to agree. Students of color—including those who are Black, Latinx, Asian American, Native American, and multiracial—frequently note and appreciate assignments or discussions of race/ ethnicity and other identity-related topics in the classroom; yet they are more likely than their White peers to report that schools place “very little” emphasis on diversity issues. Women are similarly more likely than men to believe their schools do “very little” to emphasize diversity in coursework. Furthermore, higher percentages of Black women report “very little” emphasis on equity or privilege (36%), respecting diverse perspectives (27%), and an institutional commitment to diversity (21%)— compared to high percentages of White men who believe their schools are doing “very much” in all three arenas (20%, 24%, and 34%, respectively). First-gen students are also more likely than their classmates whose parents completed college to note “very little” diversity coursework. Synthesizing these data, students who are traditionally underrepresented and marginalized—arguably the students who have the most personal experience with issues of diversity—see their schools as doing less to promote diversity and inclusion than those who are privileged in terms of their race/ethnicity, gender, and parental education.

As part of a broad curriculum that sets up students for their future practice, law schools should teach students diversity skills—a set of skills that facilitate success in our increasingly globalized society, ranging from personal reflection to the tangible tools lawyers can use to combat discrimination. Law schools that succeed at these diversity-related endeavors will be preparing our nation’s newest lawyers to meet the full range of challenges ahead.