Preparing Law Students for a Multicultural World

Alongside developing analytical skills and learning about the law, law students must learn how to work effectively in a diverse, multicultural environment. Law schools have a responsibility to prepare their students by providing them with the knowledge, skills, and experiences necessary to navigate complex cultural dynamics. This can be achieved through a variety of means, including offering courses on cross-cultural communication and conflict resolution, providing opportunities for international study and internships, and fostering a diverse and inclusive campus community. By equipping law students to work effectively in a multicultural world, law schools can help to ensure their graduates are well-prepared to meet the challenges of an interconnected global society.

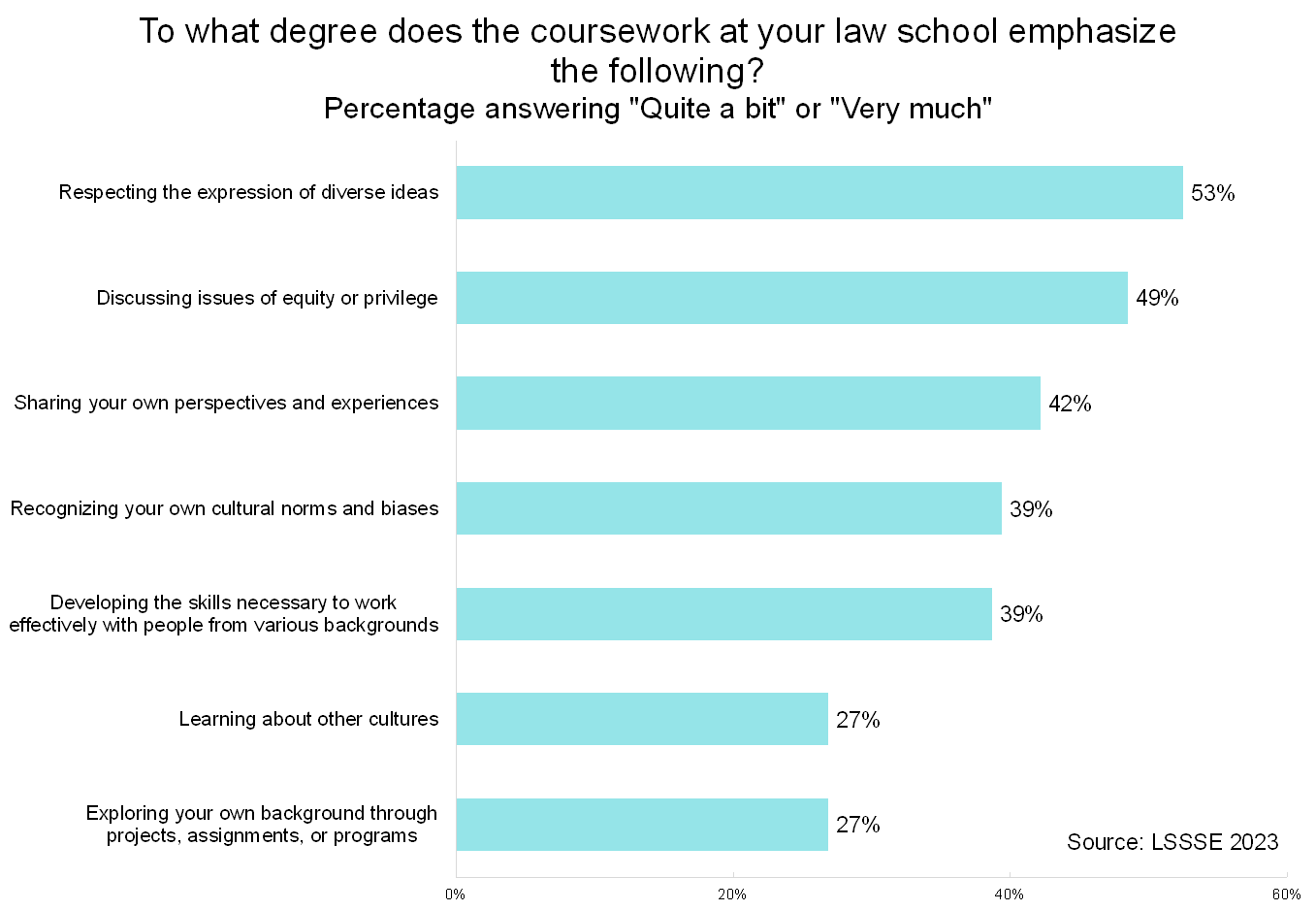

We wanted to understand the degree to which law students feel that their law school's coursework helps them learn to interact effectively and respectfully with others who are different from them. LSSSE asks students about the degree to which the coursework at their law school emphasizes various foundational principles of diversity and inclusion. In 2023, more than half of law students (53%) felt their coursework placed quite a bit or very much emphasis on respecting the expression of diverse ideas, and nearly as many (49%) experienced an emphasis on discussing issues of equity or privilege. However, only slightly more than a quarter (27%) of students felt that their law school emphasized learning about other cultures, and the same percentage felt their law school emphasized exploring students’ own backgrounds through projects, assignments, or programs

By creating a climate of academic freedom and intellectual diversity, law schools promote the values of democracy and human rights, which are essential for the rule of law and social justice. Only 14% of students said their law school placed very little emphasis on respecting the expression of diverse ideas, so clearly law schools value broader ideals around freedom of expression. However, law students also need to understand their own cultural background and how it shapes their worldview, values, and assumptions. By exploring their own identity and experiences, law students can gain insight into how they perceive themselves and others and how they relate to people who are different from them. This can help them respect and value others' contributions. Furthermore, by understanding their own cultural background, law students can also identify areas where they may need to learn more or adapt their behavior to work effectively in a multicultural context.

Courses on cultural diversity and inclusion, implicit bias, and cross-cultural communication can provide students with the knowledge and skills necessary to work effectively in a multicultural environment. Additionally, incorporating case studies and simulations that expose students to real-world scenarios can help students to develop practical skills in navigating complex cultural dynamics. By providing students with opportunities to engage in critical reflection and dialogue, law schools can help students to become more aware of their own biases and to develop strategies for mitigating their impact.

SPOTLIGHT ON: Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Law Students

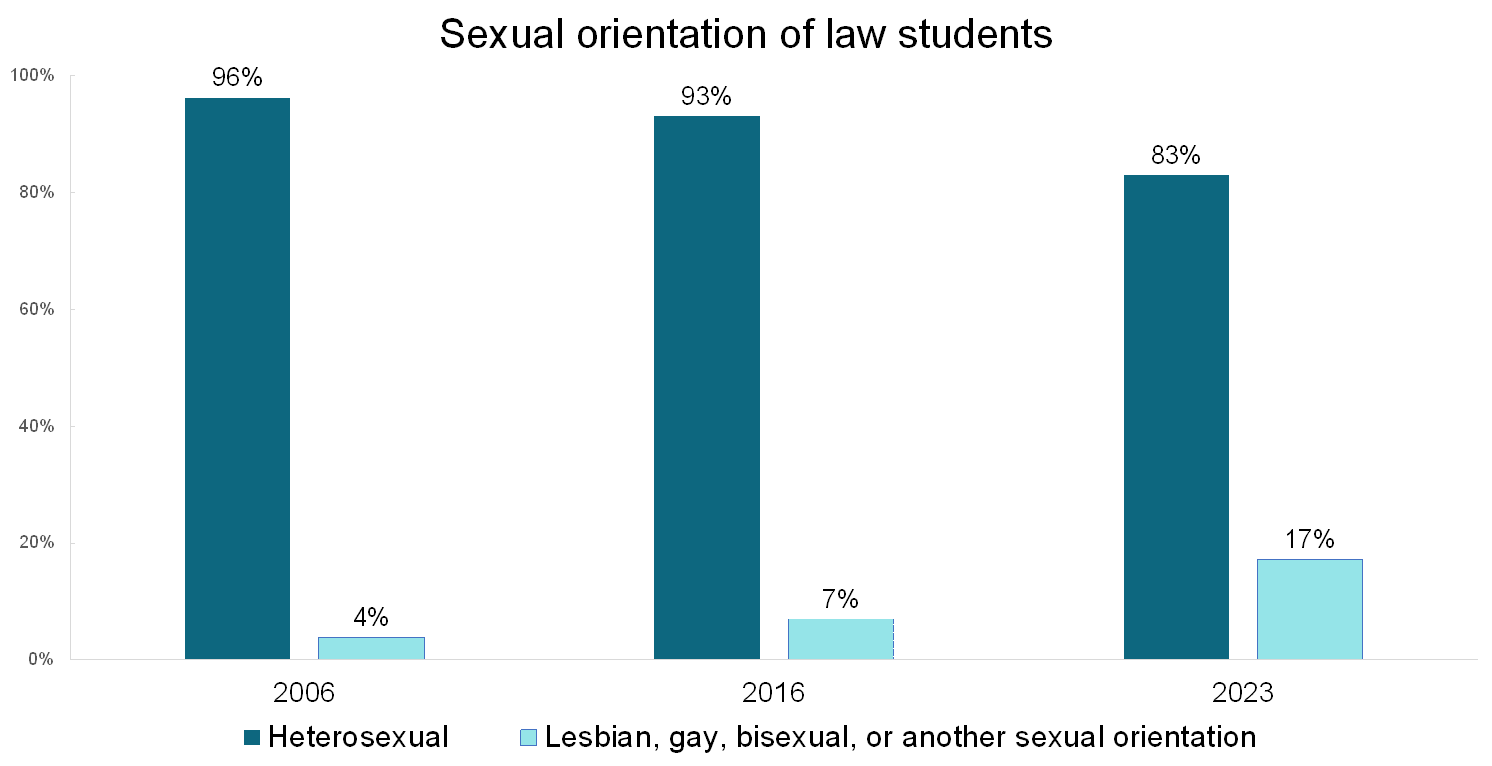

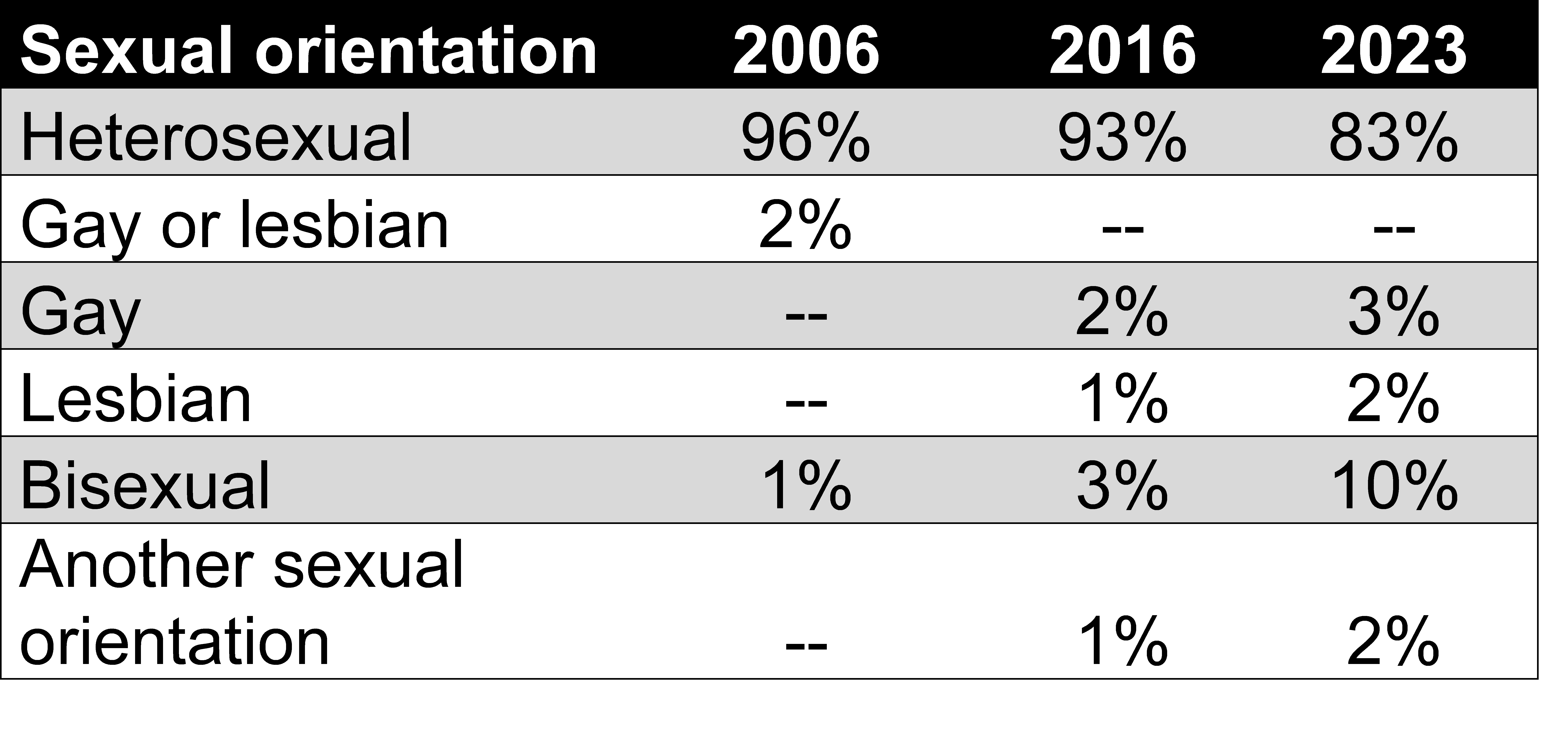

The percentage of law students who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or another non-heterosexual sexual orientation (LGB+) has grown dramatically over the last twenty years. When LSSSE first began asking about sexual orientation in 2006, 96% of law students identified as heterosexual, 2.5% were gay or lesbian, and only 1.3% were bisexual. The numbers had shifted noticeably by 2016, when the sexual orientation question was revamped slightly to be more inclusive. That year, 93% of law students were heterosexual, 2.3% were gay, 1.1% were lesbian, 2.6% were bisexual, and 0.9% were of another sexual orientation. However, by 2023, only 83% of law students identified as heterosexual. Three percent were gay, 1.7% were lesbian, 2% had another sexual orientation, and a full 10% identified as bisexual.

-- indicates response option was not available that year

-- indicates response option was not available that year

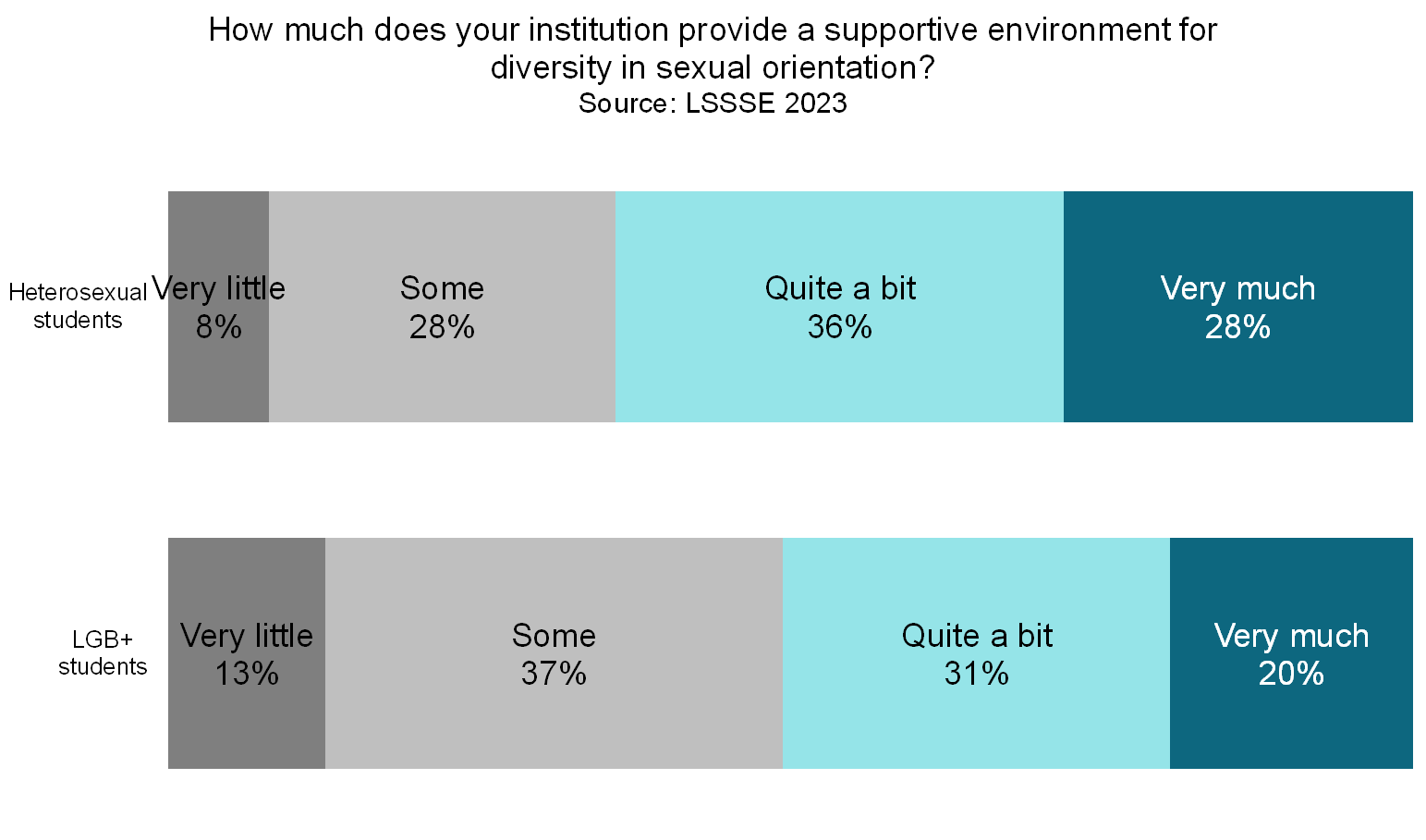

LGB+ students are somewhat less comfortable in law school relative to their heterosexual peers. For example, 72% of LGB+ students feel that they are part of the law school community compared to 77% of heterosexual students. Only half (50%) of LGB+ students believe that their law school places quite a bit or very much emphasis on ensuring that they are not stigmatized because of their identity (racial/ethnic, gender, religious, sexual orientation, etc.) compared to 61% of heterosexual students. Similarly, only about half (51%) of LGB+ students believe that their law school is a supportive environment for diversity in sexual orientation compared to just under two-thirds (64%) of heterosexual students.

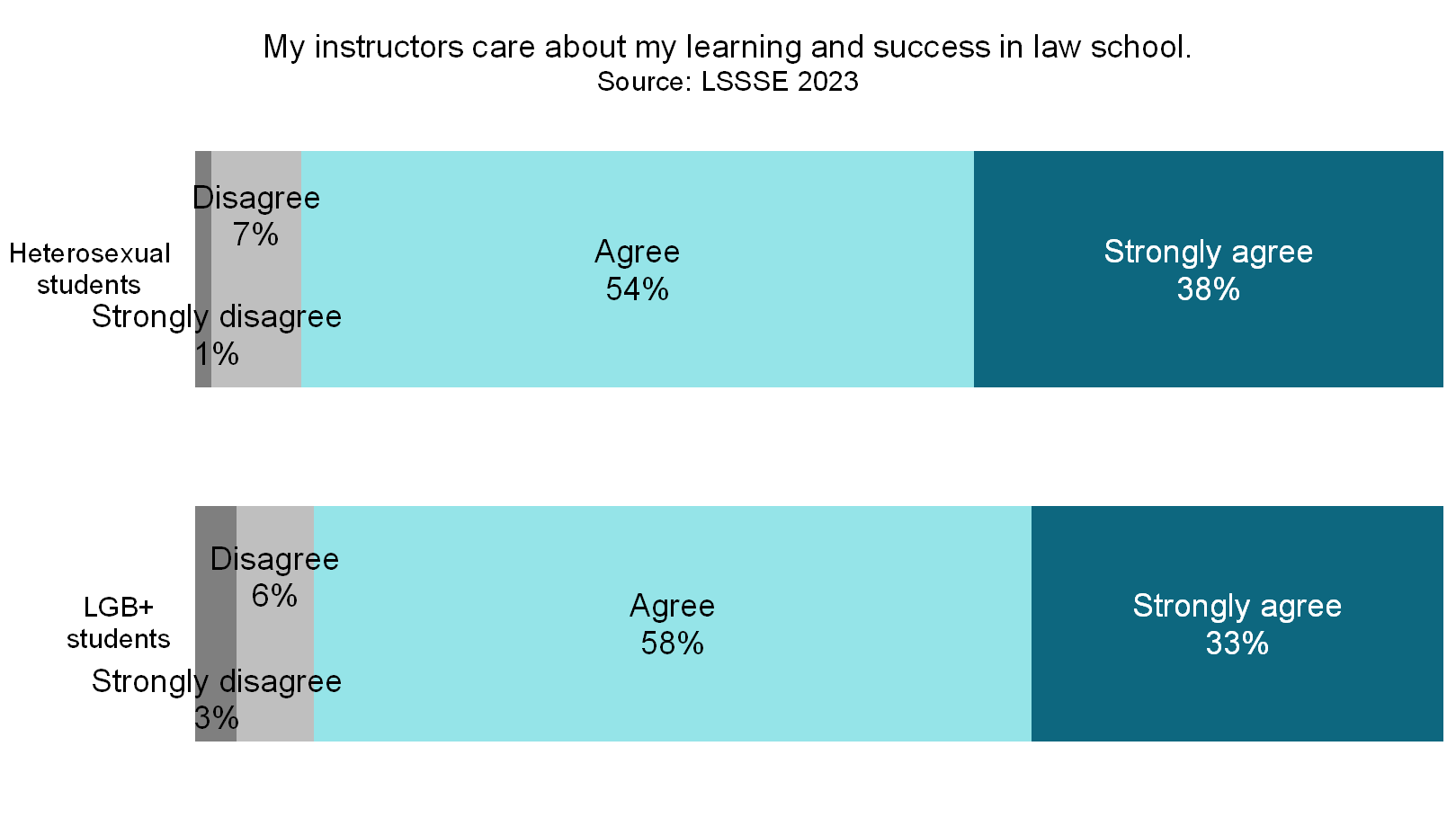

Despite the perception of a somewhat chilly climate overall, LGB+ law students are nearly equally likely as heterosexual law students to have strong relationships with law school faculty. LGB+ students rate their relationships with faculty on average 5.2 on a seven-point scale, compared to 5.3 for heterosexual students. A full 91% of LGB+ students believe their instructors care about their learning and success in law school, nearly equal to the 92% of heterosexual students who feel that way. Around four in five LGB+ and heterosexual students consider at least one instructor a mentor whom they feel comfortable asking for advice or guidance. Clearly, most students find help and support from their law school faculty, regardless of their sexual orientation.

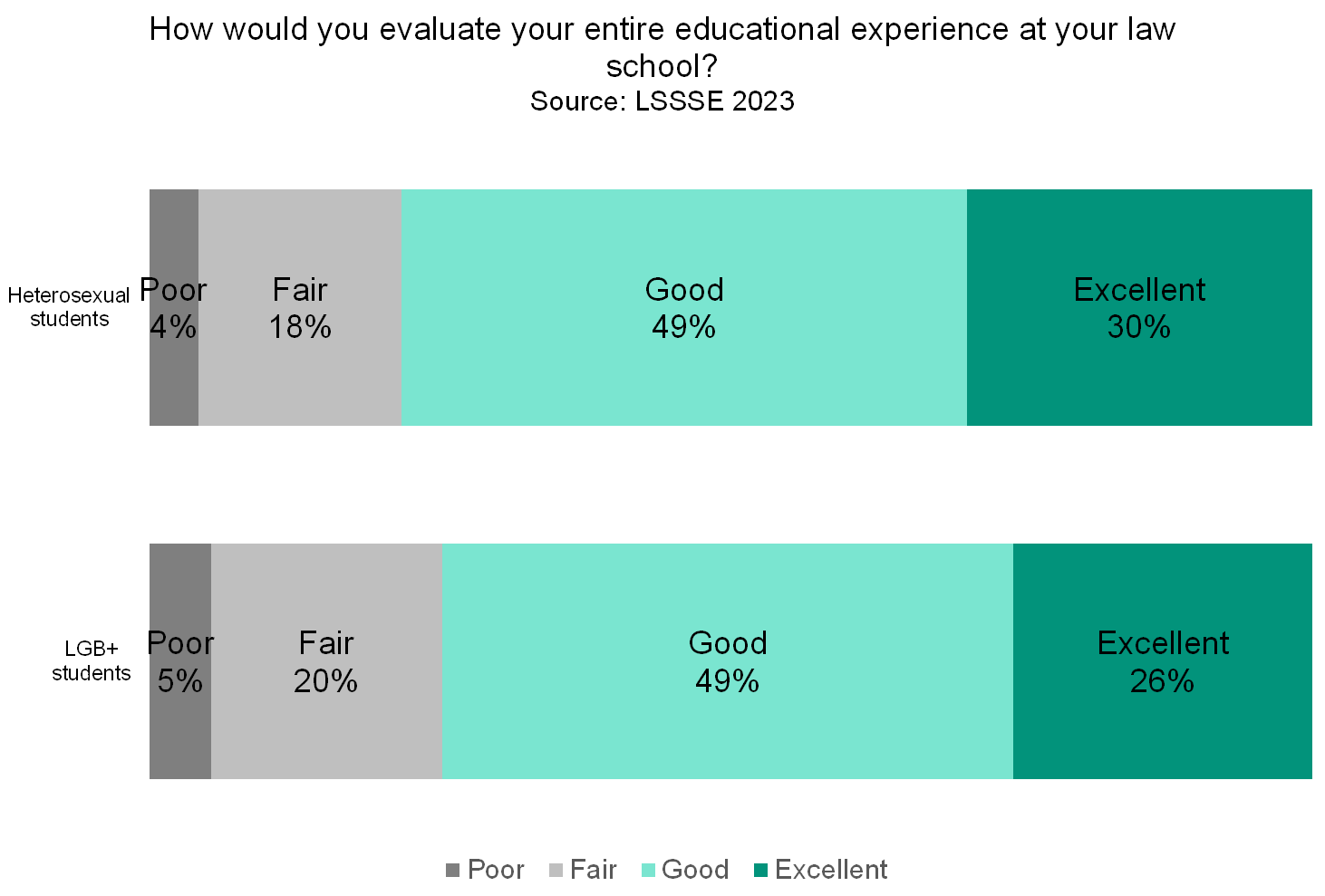

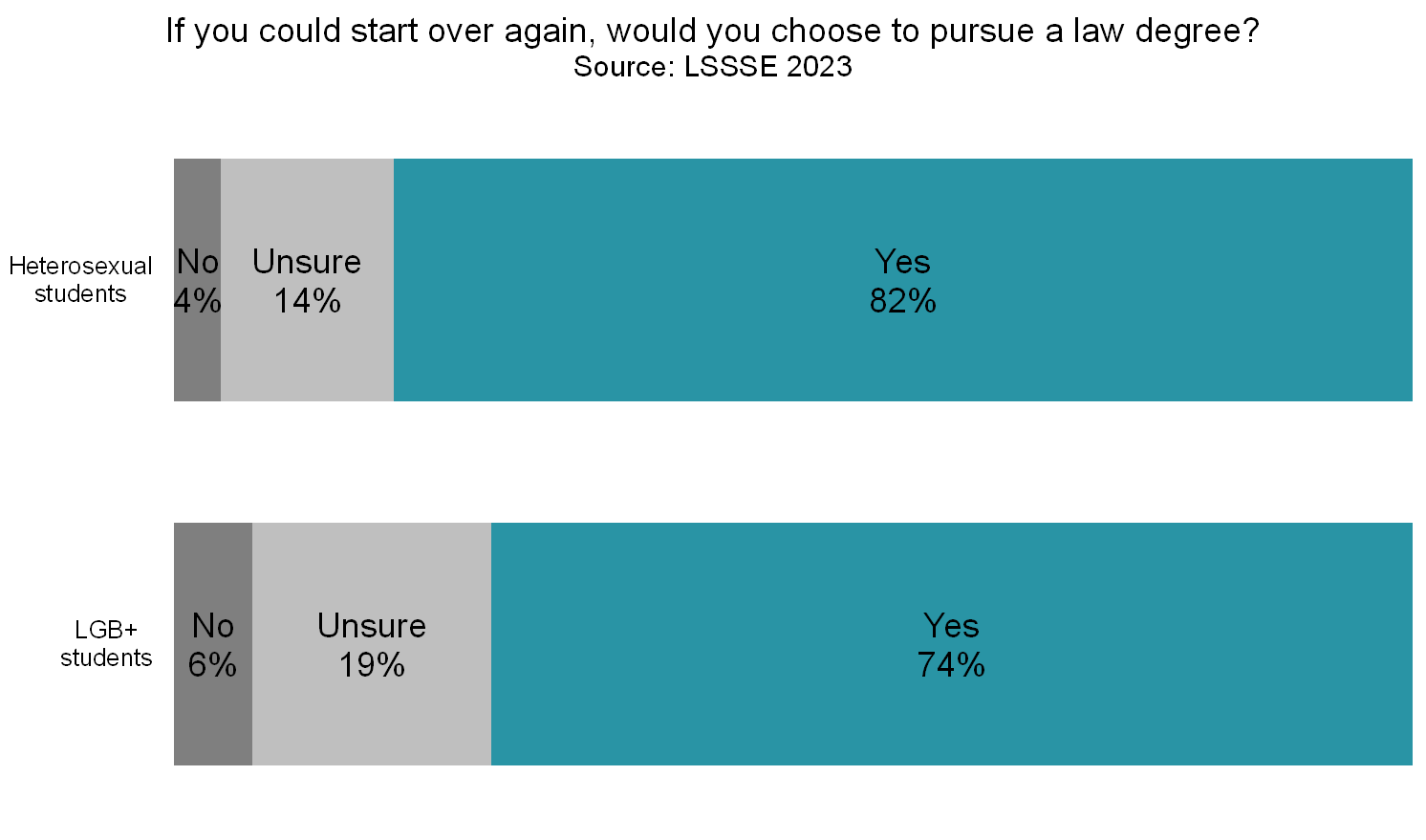

LGB+ students are somewhat less satisfied with their overall experience at law school compared to heterosexual law students. Three-quarters (75%) or LGB+ students rate their experience “good” or “excellent” compared to 78% of heterosexual students. However, LGB+ students are much less likely to be sure that they would pursue a law degree if they could start over. Just under three-quarters (74%) of LGB+ students said they would pursue a law degree and 19% were unsure. More than four in five (82%) heterosexual students would choose law school again and only 14% were unsure. Clearly, LGB+ law students are more likely than heterosexual law students to have regrets or misgivings about the path they selected.

Given that the population of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and other non-heterosexual students is growing rapidly in law schools, the concerns that these students have about the law school experience deserve particularly careful attention. LGB+ law students are less likely to feel that they belong, more likely to feel stigmatized, and more likely to question whether attending law school was the correct choice for them. Interestingly, most LGB+ students feel that their instructors care, and they are equally likely as heterosexual students to have an instructor that they consider a mentor. Perhaps law schools can use these personal connections to identify and address the concerns of their lesbian, gay, bisexual, and other non-heterosexual students in order to ensure equitable educational opportunities and a more supportive law school environment.

Guest Post: The Normative and Legal Case For Affirmative Action Programs for the Descendants of Persons Enslaved In America

Guest Post: The Normative and Legal Case For Affirmative Action Programs for the Descendants of Persons Enslaved In America

Erika K. Wilson

Professor of Law, Wade Edwards Distinguished Scholar, and Director of the Critical Race Lawyering Civil Rights Clinic

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

The Supreme Court’s recent decision in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President & Fellows of Harvard Coll., 143 S. Ct. 2141 (2023) arguably ended race-conscious admissions policies as we know them. While the Court did not expressly overrule diversity as a compelling state interest, it did find that the way in which Harvard and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill were using race to achieve diversity was unconstitutional. The majority opinion observed that universities undermined their stated interest in obtaining a racially diverse class by relying upon “opaque racial categories.” It identified as particularly problematic categorizing all Asian applicants together with no distinctions made between South and East Asians; the arbitrariness of the Hispanic categorization; and the under inclusiveness of the Middle Eastern classification. Justice Gorsuch’s concurring opinion made a similar observation with respect to the categorization of Black students:

The “Black or African American” category covers everyone from a descendant of enslaved persons who grew up poor in the rural south, to a first-generation child of wealthy Nigerian immigrants, to a Black-identifying applicant with multi-racial ancestry whose family lives in a typical American suburb.

Gorsuch’s critique is salient because the original purpose of race-conscious affirmative action programs was to remediate the multi-generational effects of slavery and the afterlives of slavery. Yet, as documented by legal scholars like Angela Onwuachi-Willig, in the early 2000s Black students at elite universities were overwhelmingly mixed-race students, or first- or second-generation Black Americans, meaning their parents and/or grandparents were immigrants. Lani Guinier and Henry Gates raised concerns in 2004 because only one-third of Harvard’s Black undergraduate students were from families in which all four grandparents were born in America, descendants of persons enslaved in America.

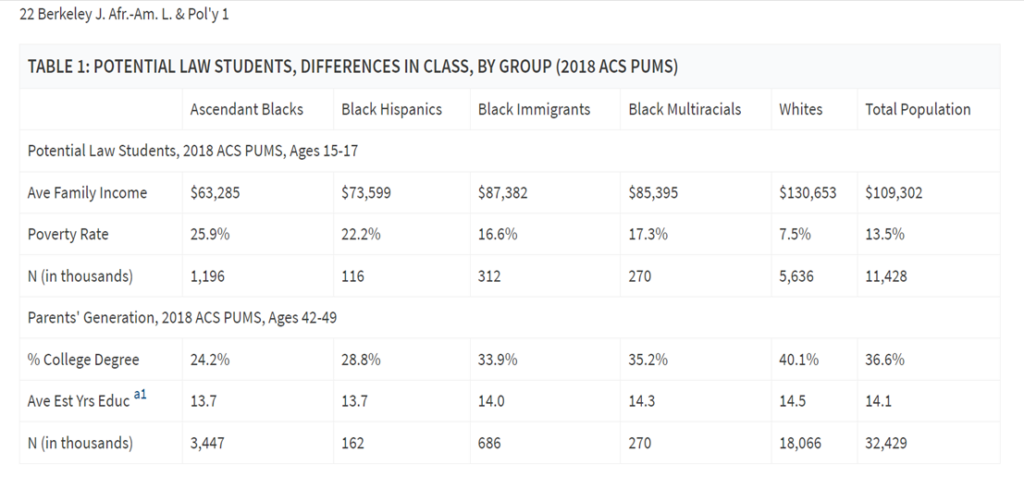

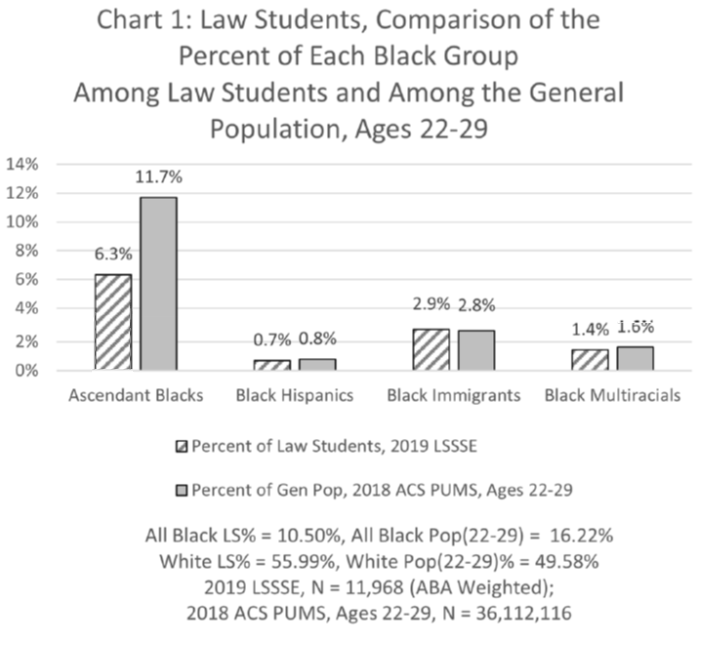

Recent research by Kevin Brown and Kenneth Dau-Schmidt relying on LSSSE Survey data shows that not much has changed since the early 2000s. Similar patterns of disproportionate representation of what Brown and Dau-Schmidt call “ascendant Blacks” (those with two American-born Black (non-biracial) parents) exists in law school enrollment today. The data show three noteworthy trends:

First, while structural racism impacts all Black people in America, it impacts some groups more acutely. As they write in their article, ascendant Black law students have lower average family incomes, higher poverty rates, and are less likely to have parents with a college degree.

Second, all Black people, except Black Immigrants (defined as Black people with at least one parent not born in America), are underrepresented among law students; furthermore, the extent of underrepresentation is much worse for ascendant Black law students than for other Black law students.

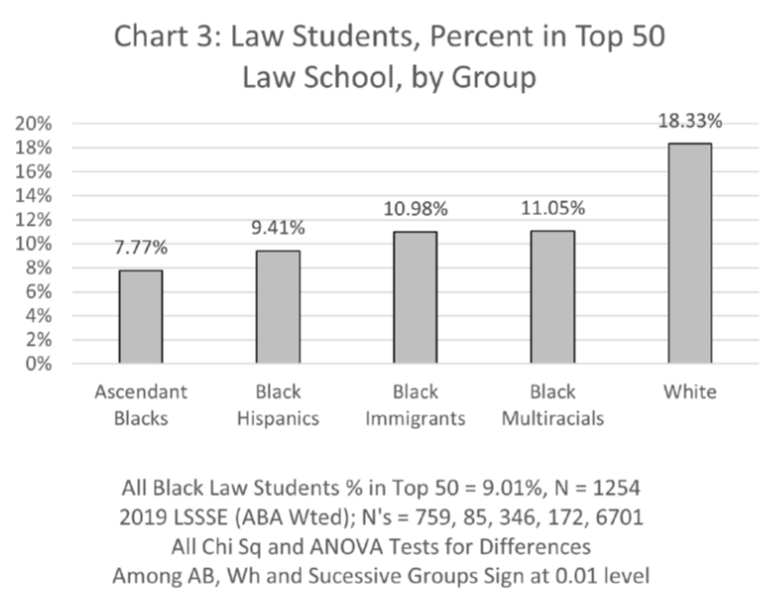

Third, ascendant Black law students are underrepresented at Top 50 law schools relative to their representation within the population of Black people in America, and relative to all other groups of Black law students.

The data and their implications should inform the path universities take to reinvent their affirmative action programs. Diversity is still recognized as a compelling state interest. Universities can and should fashion admissions programs that seek to increase representation of Black students who are the descendants of persons enslaved in America. To be sure, they should also continue to make efforts to increase representation of all Black groups because race remains a salient and undeniable barrier for all Black people in America. Yet the unique burdens and history of subordination linked directly to American slavery imposes a special remedial obligation on universities to provide access to Black students who are the descendants of persons enslaved in America. This is especially true for elite universities such as Harvard and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill that directly benefited from slavery.

In Justice Clarence Thomas’ concurring opinion in Students for Fair Admissions, he offers a potential Constitutional path for doing so. He suggests that a classification consisting of descendants of persons enslaved in America is not a racial category. He contends that:

[The 1866 Freedmen’s Bureau Act ] applied to freedmen (and refugees), a formally race-neutral category, not [B]lacks writ large. And, because “not all [B]lacks in the United States were former slaves,” “ ‘freedman’ ” was a decidedly underinclusive proxy for race.

His comments, as other scholars have noted, raise questions as to the legality of an affirmative action program centered on descendants of persons formerly enslaved in America, as such a categorization may not be subject to the same level of heightened scrutiny as a race-based classification. Nonetheless, Thomas’ assertion that “freedmen” was not a racial categorization is admittedly dubious. But such a targeted program might also be justified under the remedial justification for race conscious policies. Thus, universities should take Thomas seriously. They should fashion admissions programs aimed at increasing the representation of Black students who are the descendants of persons enslaved in America. LSSSE data and history demonstrate the normative case for doing so.

Working Effectively with Others

Last month, we looked at characteristics and perspectives of law students who developed the ability to learn independently. This month, we will look at students who have substantially improved their ability to work effectively with others during law school.

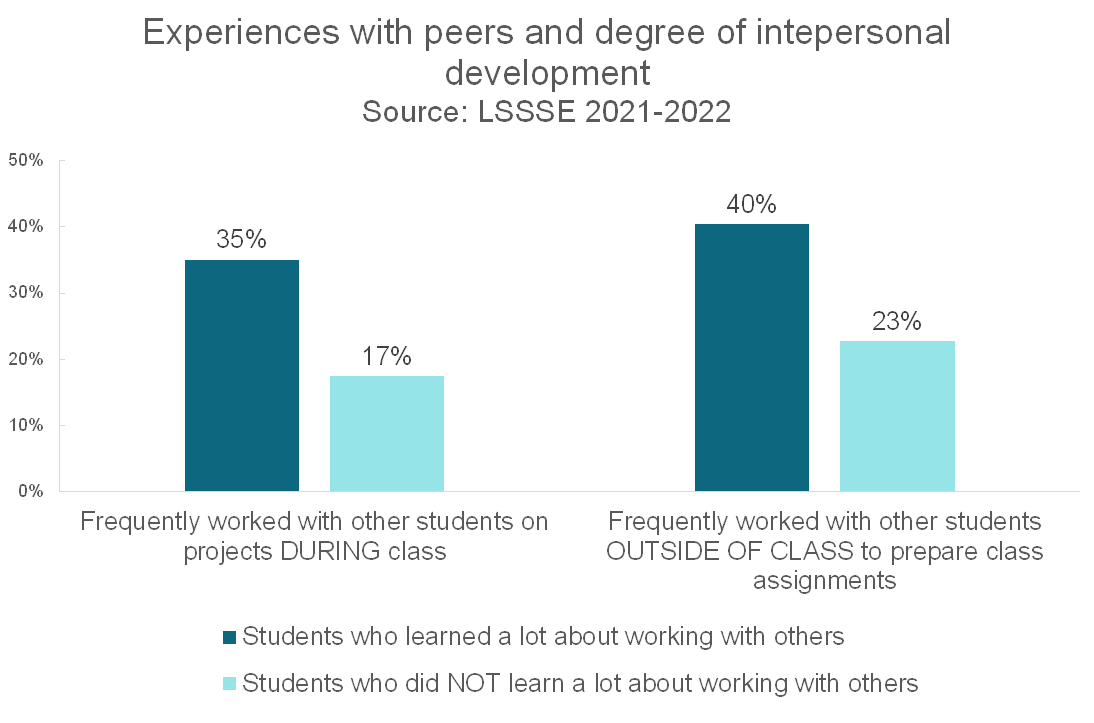

Developing skills in working effectively with others may be at least partially about exposure. Students who learned a lot about working with others were more likely to frequently work with classmates during class and also more likely to frequently work with classmates outside of class.

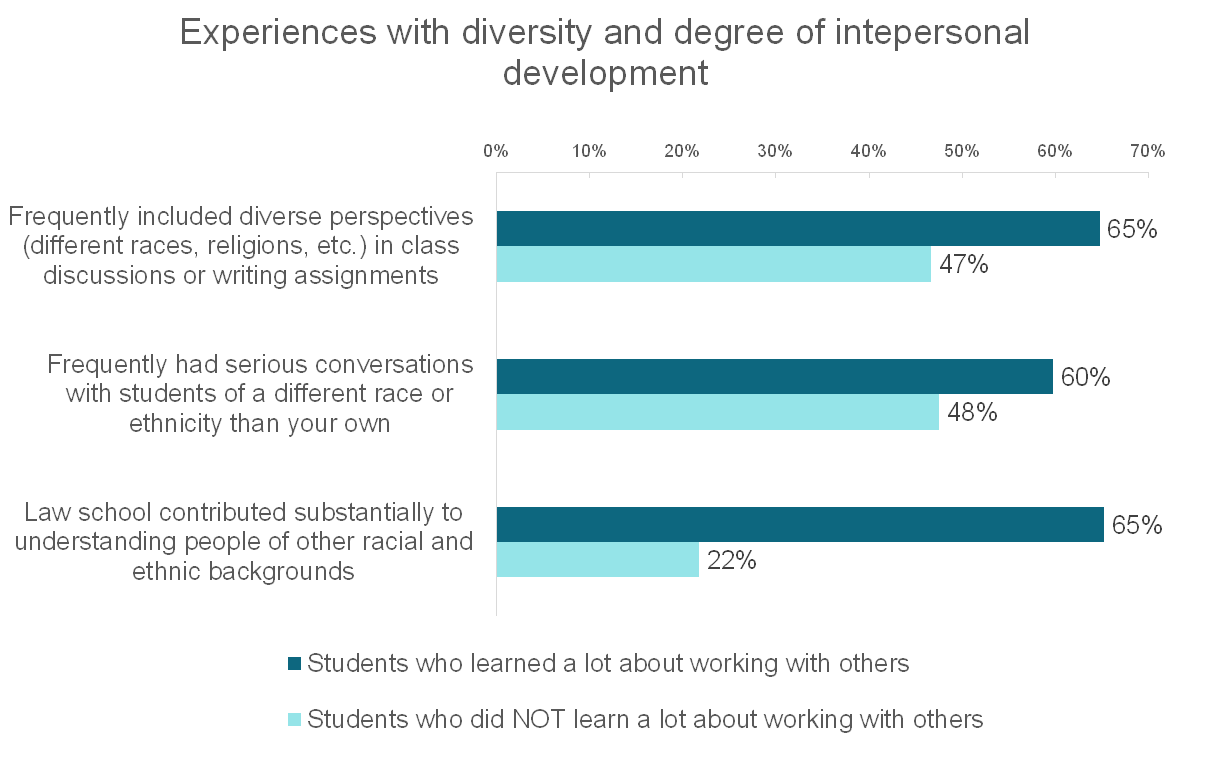

Perhaps not surprisingly, sustained contact with others while working toward a mutual goal appears to be associated with increased awareness of issues of diversity. Students who learned a great deal about working with others were more likely to include diverse perspectives in course assignments and class discussions by considering issues of race, religion, sexual orientation, gender, or political beliefs more often than their peers. Three in five (60%) of students who learned a lot about working with others frequently had serious conversations with students of a different race or ethnicity than themselves, but only 48% of other students did so. However, the largest difference is in the degree to which students feel that law school contributed substantially to understanding people of other racial and ethnic backgrounds. Two-thirds (65%) of students who learned a lot about working with others felt this way compared to a meager 22% of students who did not learn a lot about working with others.

We must consider, however, that students who feel their law school contributed substantially to their ability to work effectively about others may feel more engaged and positive about their law school experience overall compared to their colleagues who did not experience very much personal development in this area. The students who learned how to work with others were also more likely to understand themselves quite a bit better because of their time at law school (73% vs. 35% of students who did not learn much about working with others) and to be more satisfied with their overall law school experience (89% vs. 65%). There is likely a constellation of environmental and personal factors that influence how students learn to engage with others and what value they get from these interactions. However, it seems likely that students who work with others, both during class and outside class, develop more collaboration skills and hone their ability to more deeply understand the perspectives of those who do not share their background.

Better than BIPOC

Meera E Deo, JD, PhD

Meera E Deo, JD, PhD

The Honorable Vaino Spencer Professor of Law, Southwestern Law School

Director, Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE)

We should be precise with our language, especially when talking about race. In “Better than BIPOC,” I argue that BIPOC is a flawed term for empirical scholars to use, one that prioritizes historical oppression over ongoing realities and relies on virtue signaling rather than working toward meaningful change. In my previous essay “Why BIPOC Fails,” I explain how BIPOC can be misleading, confusing, and contribute to the invisibility of the very groups that should be centered in particular contexts. Thus, without the deep investment of community engagement and review, new labels—like BIPOC—run the risk of causing more harm than good. Instead, we should continue to use the term “people of color” when referencing this group in comparison to whites, while “women of color” is useful when considering raceXgender intersectionality. Banding together for mutual support and action has been critical for people from marginalized identities as they have worked toward lasting social change. Additionally, it is often important to disaggregate data to report on individual groups that could otherwise get lost under these larger umbrella terms.

The experiences of various communities in law school help illustrate the point that academics, advocates, and allies should use be careful in their language usage—especially when dealing with data. Grouping populations together is often instructive. It can also be necessary to disaggregate the data to deal with separate communities individually. Law student debt and experiences with issues of diversity are particularly instructive in explaining both paths.

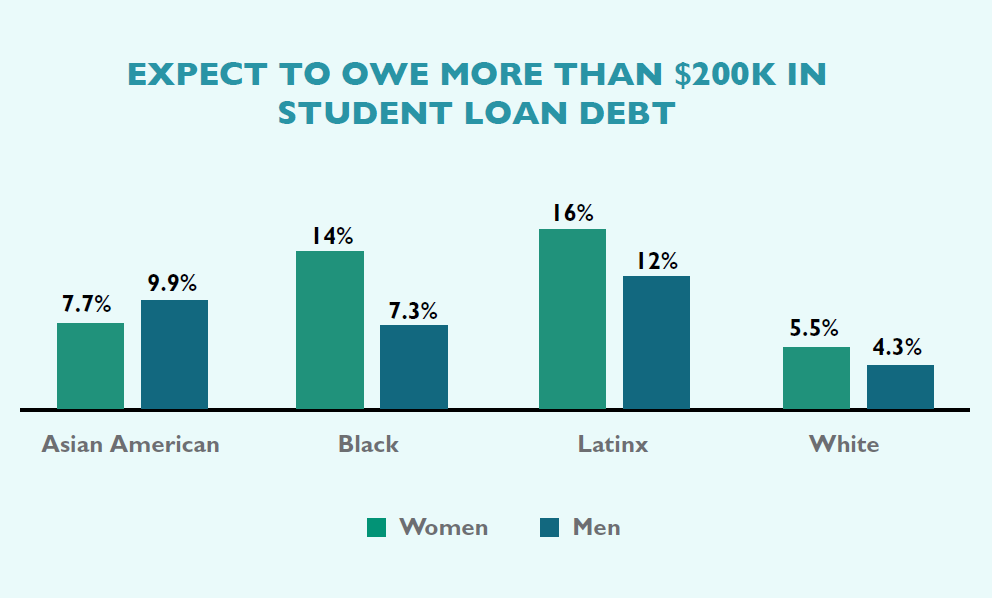

First, LSSSE data reveal that students of color carry more educational debt than white students. Here, it is appropriate and useful to group students of color together as a whole in comparing them with white students in terms of their overall debt loads. However, we can dig deeper to consider the intersectional experience of gender combined with race. If we ignore gender in this context, we run the risk of masking the distinct experiences of women of color compared with men of color as well as other groups. And there are differences. As I write in the article, “[H]igher percentages of Women of Color (23%) graduate with over $160,000 in law school debt, as compared with Men of Color (18%), white women (15%), and white men (12%).” While examining debt by raceXgender is thus more useful than considering race alone, being even more precise with the data and our language provides an opportunity to reveal more nuanced realities for communities within the women of color umbrella. As we share in our 2019 LSSSE Annual Report, The Cost of Women’s Success, the raceXgender groups most likely to carry the highest debt loads of over $200,000 are Latinas (16%) and Black women (14%), compared to lower percentages of Asian American women (7.7%), Black men (7.3%), Latino men (12%), and white men (4.3%). Thus, while it is correct to talk about the people of color and women of color carrying more debt than whites and those who are not women of color, it is more complete and sophisticated to explain how particular raceXgender groups—Black women and Latinas—have the highest debt loads of all. Precise racial language is instructive, particularly if we seek to craft solutions to ameliorate these challenges that are directly responsive to the needs of the populations affected.

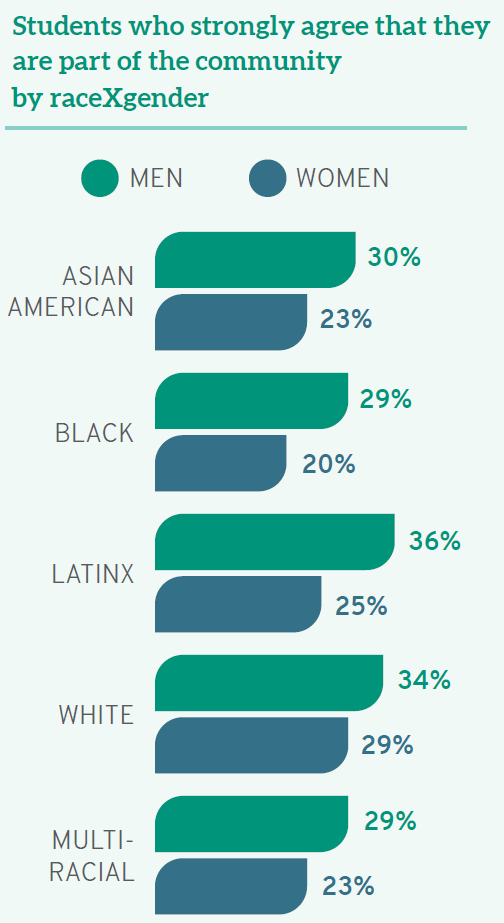

Student experiences with diversity provide another example of the benefits of careful language usage. Compared to their white peers, students of color have distinct opinions and experiences in law school when considering issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion. For example, although almost one-third (31%) of white law students “strongly agree” that they see themselves as part of the law school community, students of color are less likely to agree. As with debt levels, there are again additional distinctions based on raceXgender. In Better than BIPOC, I draw on data from the LSSSE 2020 Annual Report, Diversity & Exclusion, noting, “Fewer than one-quarter (23%) of women of color ‘strongly agree’ that they are part of the institutional community, compared to almost one-third (31%) of men of color.” Thus, distinctions based on race alone are not as precise as those disaggregating racial data by gender. In certain contexts, we also can—and should—go further still. By looking within the category of people of color, we can determine important differences between groups that administrators, faculty, and staff should consider in order to tailor solutions to the students who most need them. For instance, when we consider student belonging, “only 21% of Native American and Black law students see themselves as part of their law school community—compared to 31% of their white classmates, 25% of multiracial students, 26% of Asian Americans, and 28% of Latinx students.” Considering the student of color narrative as one group would tell an incomplete story as Black and Native law students are even more alienated nationally than even other students of color. Addressing their concerns will require us first to understand them, then to act.

Better than BIPOC also draws from the data behind my book project, Unequal Profession: Race and Gender in Legal Academia, to share examples from the law faculty context. I use findings on student evaluations and the challenges different populations face while navigating work/life balance to suggest when we should compare faculty of color as a whole to their white colleagues, when to disaggregate by race as well as gender to examine the experience of women of color faculty, and when to look more carefully within racial and gender-based categories to reveal important distinctions that could otherwise be hidden. Beyond the context of legal education, we can apply this thesis to frameworks as diverse as political engagement, workplace harassment, elementary school integration, diversity in corporate boards, and more. Different situations will naturally call for specific groups to be named and studied directly; that context, regardless of the terms currently en vogue, should drive the data used and arguments made in any endeavor. Working collectively serves a purpose, as does disaggregating the data. Through both efforts, we can understand the unique challenges facing different groups and work collectively to address them.

Guest Post: The Imperative of Inclusive Socratic Classrooms

The Imperative of Inclusive Socratic Classrooms

The Imperative of Inclusive Socratic Classrooms

Jamie R. Abrams, J.D., LL.M

Professor of Law, University of Louisville Brandeis School of Law

Legal education is navigating multiple reform initiatives that call for scalable and versatile approaches. Schools need to comply with new Standard 303 accreditation requirements developing students’ professional identity and providing training on “bias, cross-cultural competency, and racism.” Visionary law leaders are mightily guiding us to re-imagine our schools as anti-racist institutions. Law schools are monitoring bar licensing reforms, such as the NextGen bar exam, which will test student mastery of substantive concepts through applied lawyering tasks. Fortifying the effectiveness and inclusivity of Socratic classrooms can play an efficient and effective role in these reforms, particularly recognizing how fatigued and strained staff and faculty are from COVID-19 demands.[i]

Critical theorists have argued for over half a century that the Socratic method can foster classrooms that are competitive, hierarchical, adversarial, marginalizing, privileging, and constraining, particularly for women and students of color.[ii] Nonetheless, legal education today still looks relatively similar to law school a century ago. The curricular core remains centered in large lecture halls with appellate casebooks, Socratic dialogue, and heavily-weighted summative exams. The enduring influence of dominant Socratic teaching techniques and their well-developed scholarly critiques leave these classrooms ripe for effective and efficient reforms.

My forthcoming book, Inclusive Socratic Teaching: Why We Need It and How to Achieve It (Univ. of Calif. Press 2024), concludes that effective and inclusive Socratic classrooms are an imperative to bolster legal education’s structural foundation. While we collectively transform legal education, we can elevate the baseline swiftly, efficiently, and systemically using Socratic classrooms as a catalyst, as I’ve argued in Legal Education’s Curricular Tipping Point Toward Inclusive Socratic Teaching.

Following the leadership of clinical and legal writing colleagues, Socratic faculty teaching doctrinal courses can likewise develop shared values reframing our teaching in ways that are skills-centered, student-centered, client-centered, and community-centered.[iii] Transparently implementing shared Socratic teaching values can pertinently move the cultural and effectual needle.

Student-centered Socratic teaching is a vital component to inclusive and effective Socratic classrooms. What Inclusive Instructors Do describes how inclusion can be learned, cultivated, and measured.[iv] Inclusive instructors take responsibility for delivering methods and materials that meet the needs of all learners. They learn about their students and care for them. They continuously adapt to help students thrive and belong.[v]

The speed of a girl around town is about four kilometers per hour, or two and a half if she is wearing heels over six centimeters find a sex date in your area uk. The zone of possible contact is five meters, no more. So you're getting... How much are you getting? (Damn it, they told me to do my math properly, you'll need it!) Well, like, five seconds.

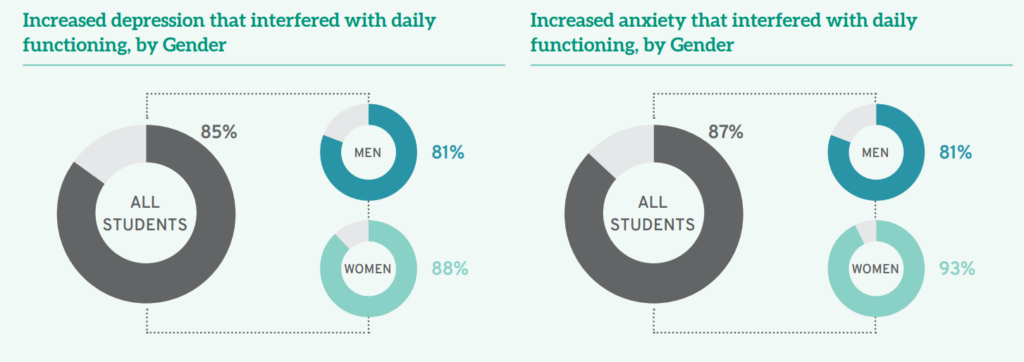

The annual Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) is an important portal into examining the needs, challenges, and lived experiences of our students collectively, particularly as it reveals a changing climate. LSSSE’s 2021 Annual Report yields a critical call to action to support our students. It reveals how students are navigating heightened levels of “loneliness, depression, and anxiety.”[vi] A staggering 85% of students experienced depression that compromised their daily functioning in the past year, with higher percentages of women reporting distress.[vii]

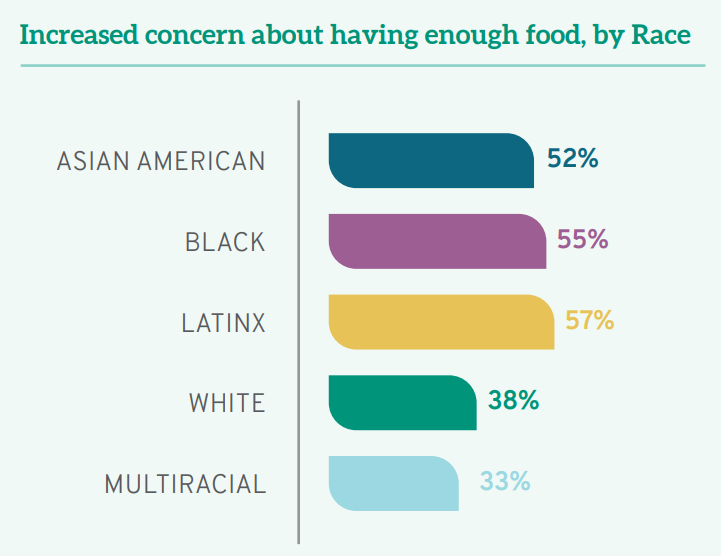

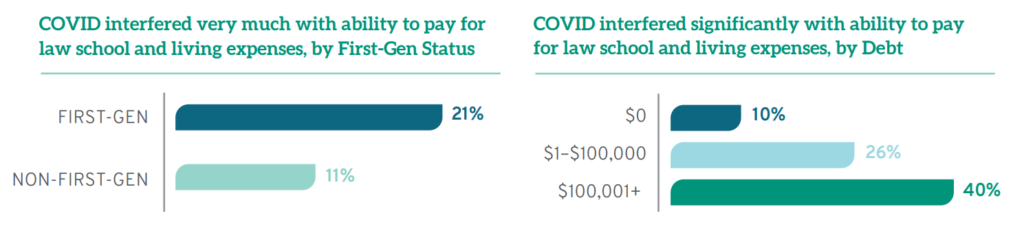

Amid COVID-19, our students have navigated our courses worried about food security, particularly Latinx, Black, and Asian American students.[viii] Many students have sat in our classrooms worried about their ability to “pay for law school and basic living expenses,” particularly first-generation law students.[ix]

Paolo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed reminds us that “trusting the people is the indispensable precondition for revolutionary change.”[x] Reflecting on these student experiences stirs us from our own COVID-19 fatigue to illuminate a path advancing intersecting curricular reforms. While no professor can alleviate the essential external challenges of our students, we can fortify the dominant Socratic classroom experience to minimize its abstract perspectivelessness. Socratic classrooms can be student-centered, skills-centered, client-centered, and community-centered, pivoting from professor-centered, power-centered, and anxiety-inducing. LSSSE’s analysis, reinforced by our direct student engagement, inspires us to reform Socratic classrooms with students, not simply for students. Sensitized to our student experiences liberates us to disrupt the status quo knowing that all students might benefit from greater connection, intentionality, and applicability in our Socratic classrooms.

Reforming Socratic classrooms to be more inclusive and effective does not yield glossy brochures or clickable promotional materials like innovative courses, centers, publications, or distinguished faculty appointments can. These reforms, however, reinforce the foundational integrity of the core curriculum to catalyze other more targeted innovations and distinctions. Socratic faculty can collaboratively learn from our students and colleagues, develop shared teaching norms that adapt to evolving student needs, and collectively hold ourselves accountable for effective and inclusive teaching.

[i] Meera E. Deo, Investigating Pandemic Effects on Legal Academia, 89 Fordham L. Rev. 2467 (2021); Meera E. Deo, Pandemic Pressures on Faculty, 170 Pa. L. Rev. Online – (2022), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4029052.

[ii] See e.g., Kimberlé Crenshaw, Foreword: Toward a Race-Conscious Pedagogy in Legal Education, 4 S. Cal. Rev. L. & Women’s Stud. 33, 34 (1994); Jamie R. Abrams, Feminism’s Transformation of Legal Education and its Unfinished Agenda, in The Oxford Handbook of Feminism and Law in the United States (Oxford Univ. Press, Eds. Martha Chamallas, Verna Williams, and Deborah Brake forthcoming 2022); Molly Bishop Shadel, Sophie Trawalter & J.H. Verkerke, Gender Differences in Law School Classroom Participation: The Key Role of Social Context, 108 Va. L. Rev. Online 30 (2022).

[iii] See Jamie R. Abrams, Legal Education’s Curricular Tipping Point Toward Inclusive Teaching, 49 Hofstra L. Rev. 897 (2021); Jamie R. Abrams, Reframing the Socratic Method, 64 J. Legal Educ. 562 (2015).

[iv] Tracie Marcella Addy, Derek Dube, Khadijah A. Mitchell & Mallory E. SoRell, What Inclusive Instructors Do 4 (2021).

[v] Id. at x (foreword).

[vi] Meera E. Deo, Jacquelyn Petzold, and Chad Christensen, The COVID Crisis in Legal Education, Law School Survey of Student Engagement Annual Report 5 (2021).

[vii] Id. at 12.

[viii] Id. at 5.

[ix] Id.

[x] Paolo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed 34 (1973).

The Changing Landscape of Legal Education: Positive Learning Outcomes

Over the past fifteen years, LSSSE has documented dramatic changes in legal education. From 2004 to 2019, the changing landscape of law school was punctuated by increasing diversity among students, rising debt levels, relative consistency in job expectations, and improvements in various learning outcomes. In spite of many challenges, law students nevertheless report relatively constant positive levels of satisfaction with legal education overall. Our 2020 special report The Changing Landscape of Legal Education: A 15-Year LSSSE Retrospective shares longitudinal findings on select metrics as well as demographic differences within variables to catalog how legal education has changed over time. In this blog post, we will share how students have increased their achievement of selected learning outcomes from 2004 to 2019.

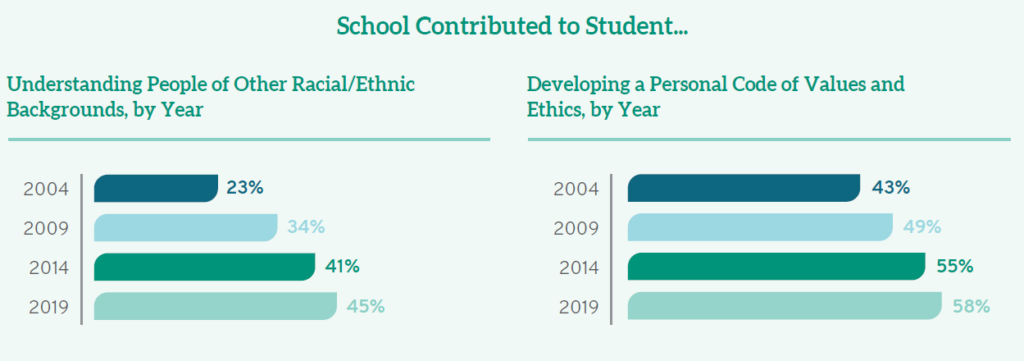

According to LSSSE data, law schools contributed to increases in a variety of perceived learning outcomes from 2004 to 2019; collectively, these point toward progress in terms of how students measure their own skills and likely in terms of actual practice-readiness of graduates. In 2004, only 23% of students saw their schools as doing “quite a bit” or “very much” to help them understand people of other racial and ethnic backgrounds; because of steady increases over the next fifteen years, especially between 2009 and 2014, almost half (45%) of students today see their schools as doing “quite a bit” or “very much” to prepare them to interact with racially diverse colleagues and clients.

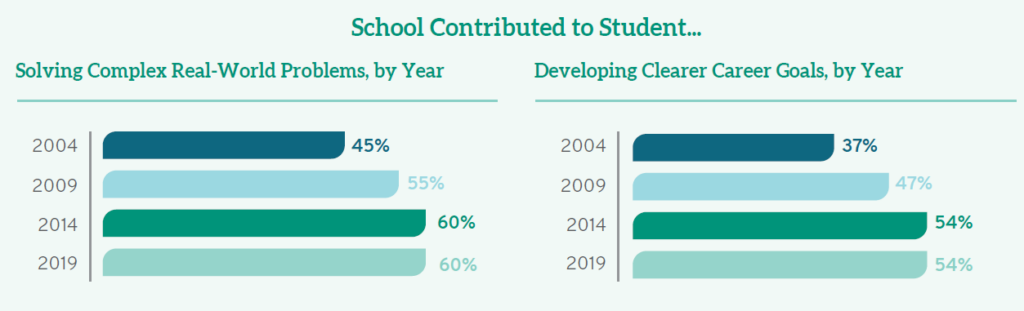

In addition, schools have increased their emphasis on professional responsibility in the past fifteen years. While even in 2004 a full 43% of students saw their schools as doing “quite a bit” or “very much” to encourage them to develop a personal code of values and ethics, that number has now grown to 58%. Schools were already prioritizing complex problem solving fifteen years ago, and students see institutional support for this skill growing over time as well. While in 2004, 12% of students believed their law schools contributed “very much” to their ability to solve “complex real-world problems,” that percentage has doubled over fifteen years so that now almost a quarter (24%) of students agree. Law schools are also encouraging students to focus on developing career goals and aspirations. In 2004, almost a quarter (23%) of all law students saw their schools doing “very little” to contribute to their developing clearer career goals; by 2019 those statistics dropped to 14%. On the flip side, while only 11% saw their schools doing “very much” in this regard in 2004, that number has risen steadily, reaching 22% in 2014 and remaining there in 2019.

Looking at the past can help prepare us for our future. To learn more, you can read the entire Changing Landscape report here.

Knowledge, Skills, and Personal Development in Law School

What does one learn in law school? In this post, we describe the areas of academic, professional, and personal development that graduating law students feel were most strongly influenced by their law school experience.

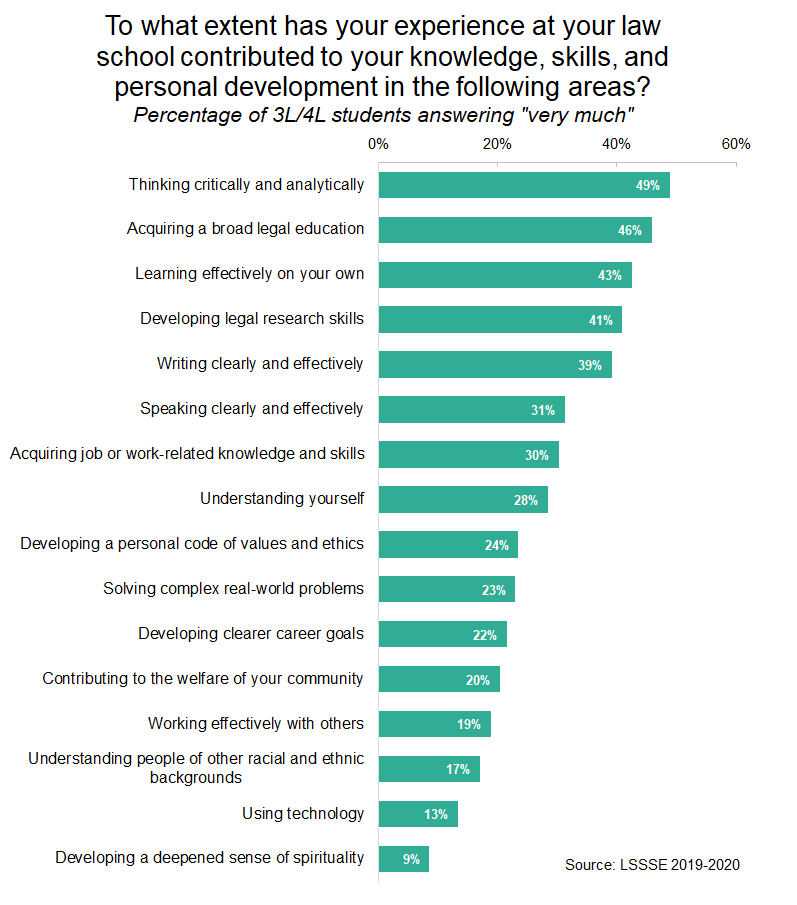

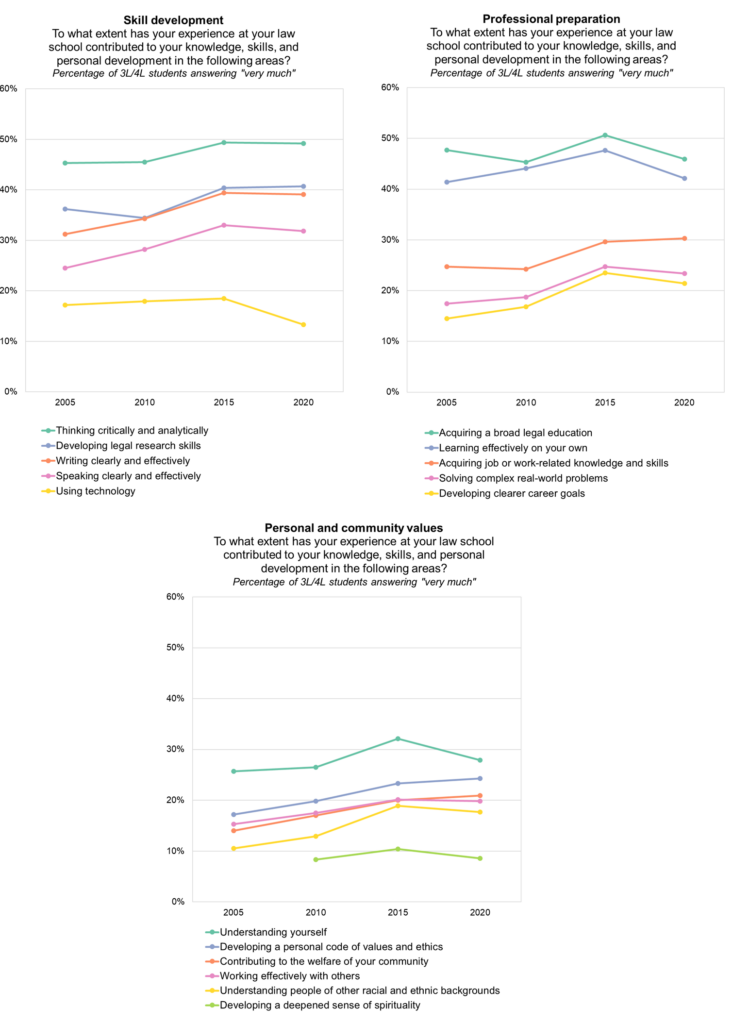

Students nearing graduation (full-time 3L students and part-time 4L students) in 2020 were most likely to say that they developed “very much” in terms of their ability to think critically and analytically (49%) and in acquiring a broad legal education (46%). Research, writing, and speaking skills were also key areas of academic and personal growth. Fewer students responded that they developed “very much” in interpersonal skills such as working effectively with others (19%) and understanding people who are different from themselves (17%).

From 2005 to the present, graduating law students have been remarkably consistent in the areas in which they say they have developed the most. Between 40% and 50% of law students over the last fifteen years feel they have acquired a broad legal education and learned how to learn effectively on their own. However, only around 20% of law students felt they had learned very much both about solving complex real-world problems and about developing clearer career goals, although these numbers have climbed over time. In terms of personal development and community values, usually about three in ten graduating students say they have made “very much” progress in understanding themselves, but only between 10% and 20% of students have made similar gains in understanding people of other racial and ethnic backgrounds. However, this area of interpersonal development has also increased noticeably over the last fifteen years.

Guest Post: Moving Legal Education to the Fourth Dimension

Guest Post: Moving Legal Education to the Fourth Dimension

Guest Post: Moving Legal Education to the Fourth Dimension

Deborah Jones Merritt

Distinguished University Professor

John Deaver Drinko-Baker & Hostetler Chair in Law

Much of law school is two-dimensional, confined to the written pages of statutes, regulations, and appellate decisions. Clients appear in our classroom hypotheticals and final exams, but they are cardboard figures designed to illustrate a point or test a legal concept. These cut-out clients lack the backstories, personalities, and secrets that three-dimensional clients embody. Nor do these cardboard clients change their circumstances or modify their goals, as real clients do. While law school is two-dimensional, law practice spreads over all four dimensions of space and time.

How do new lawyers jump from two dimensions to four? Research I conducted with Logan Cornett, Director of Research at IAALS (the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System), suggests that the transition is difficult. Our research team conducted 50 focus groups with new lawyers and their supervisors to explore this transition. Our groups spanned 18 locations nationwide and included 200 demographically diverse lawyers. In addition to their demographic diversity, our focus group members represented a wide range of employment contexts: federal, state, and local government; nonprofits; firms of all sizes, and solo offices. They also worked in more than 50 distinct practice areas, ranging from animal rights to workers compensation.

These focus groups generated more than 1500 pages of transcribed comments, which we analyzed using standard tools of qualitative research. NVivo software helped us organize and code the data; we then followed the principles of grounded theory to draw insights directly from the data. The results overwhelmingly support four conclusions: (1) More than half of new lawyers engage directly with clients during their first year, often as early as the first week. (2) Many of these lawyers also take primary responsibility for client matters. (3) Although some employers offer careful supervision and training, many do not. Instead, many new lawyers operate solo—even when they receive a paycheck from an employer. (4) To practice effectively under these circumstances, new lawyers must possess twelve foundational competencies or “building blocks.”

We discuss these twelve building blocks at length in our report, Building a Better Bar: The Twelve Building Blocks of Minimum Competence. For quick reference, the blocks are:

- The ability to act professionally and in accordance with the rules of professional conduct

- An understanding of legal processes and sources of law

- An understanding of threshold concepts in many subjects

- The ability to interpret legal materials

- The ability to interact effectively with clients

- The ability to identify legal issues

- The ability to conduct research

- The ability to communicate as a lawyer

- The ability to see the “big picture” of client matters

- The ability to manage a law-related workload responsibly

- The ability to cope with the stresses of legal practice

- The ability to pursue self-directed learning

Even a quick glance suggests that many of these building blocks are three- and four-dimensional, rather than two-dimensional. New lawyers must act professionally, not just know the written rules of professional conduct. They must also counsel clients who live multi-faceted lives and who change their goals over time. Understanding legal processes, seeing the big picture of client matters, managing workloads, communicating as a lawyer, and coping with the stresses of legal practice are all three- and four-dimensional tasks.

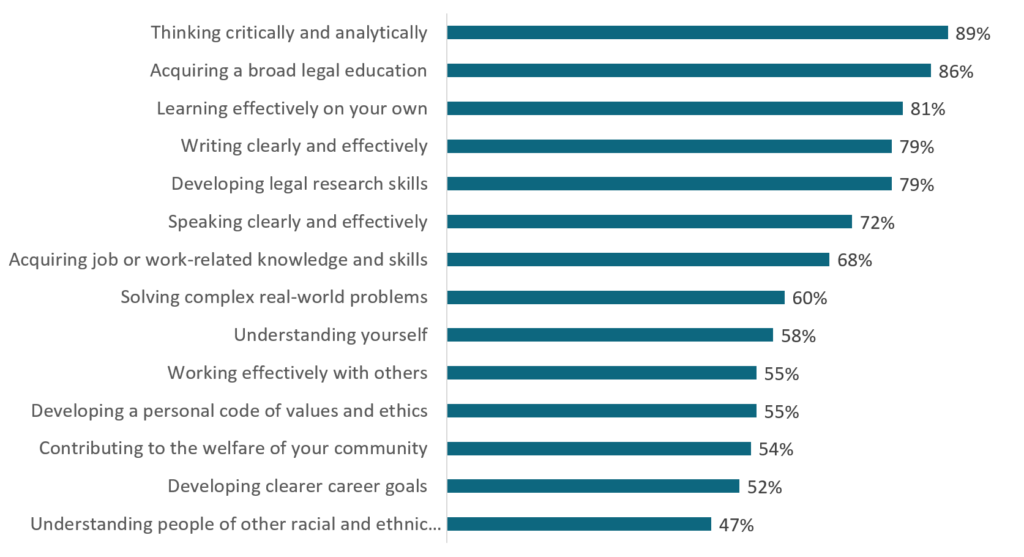

Law schools have made significant progress in teaching students to navigate the complex dimensions of law practice: Clinics and other experiential offerings have expanded over the last 20 years. In LSSSE’s most recent survey, two-thirds of law students reported that their legal education helped them either “very much” or “quite a bit” to acquire job-related knowledge and skills. Sixty percent expressed similar appreciation of law school’s contribution to learning how to solve “complex real-world problems.”

But the LSSSE survey also points to areas of needed improvement. Only about half of respondents believed that law school had helped them “very much” or “quite a bit” in understanding people of other racial and ethnic backgrounds, developing clear career goals, shaping a personal code of values and ethics, or working effectively with others. Although phrased differently than our twelve building blocks, these competencies relate to the complex skills we identified in our research.

Once the LSSSE respondents enter practice, moreover, they may be less sanguine about their preparation. Many new lawyers in our focus groups told us that their first year of practice was a “trial by fire.” They struggled to counsel clients, develop strategies, and resolve matters with little supervision. Once on the job, they discovered that they needed more job-related skills than law school provided. Why, they asked, didn’t law school better prepare them for the full range of their work?

Legal educators often say that employers are better suited than professors to teach advanced practice skills. Law school, they argue, properly focuses on teaching basic skills (such as case analysis), threshold concepts, and detailed doctrine. But our research partially disputes that claim. New lawyers undoubtedly need the basic skills and threshold concepts that law school instills. But once they possess those competencies, employers are quite capable of teaching junior lawyers specialized doctrine. Indeed, many new lawyers practice in fields that they never studied. In contrast, employers lack both time and expertise to teach advanced skills like counseling clients, gathering relevant facts, and negotiating with adversaries.

Law school is the place to learn these complex skills. Clinicians and other skills professors know how to teach cognitive skills like counseling, fact gathering, and negotiating. They also know how to provide feedback to novices and coach them to competence. Workplaces offer opportunities to hone professional skills, but schools are the best place to learn the basics.

Some lawyers think of counseling, fact gathering, and negotiating as soft skills that can’t be taught. But there’s nothing soft or unteachable about these skills. They’re harder to teach than the skills we teach in the first-year curriculum, but they’re quite teachable. Think of these skills as the second stage of learning to think like a lawyer. First-year students learn how to analyze legal materials, synthesize those materials, and apply legal rules to hypothetical problems. Those skills lay a foundation for learning more complex skills like counseling, fact gathering, and negotiating. The latter skills require students to add multi-dimensional clients, uncertain legal processes, and shifting fact patterns to their two-dimensional analyses.

If we want our graduates to serve clients effectively, law schools must step into the fourth dimension. Before graduation, every student should learn to counsel clients, gather facts, negotiate, and perform the other multi-dimensional skills embodied in the twelve building blocks listed above. The LSSSE survey can help us continue to track progress on that essential front.

The word "impotence" is considered outdated and is rarely used in modern medical sources. It is used when more than 75% of attempts to get an erection during sexual intercourse end in failure. A more https://www.faastpharmacy.com/ accurate and modern term is "erectile dysfunction", which describes a variety of problems in bed in young and mature men.

Guest Post: Legal Education and the Illusion of Inclusion

Guest Post: Legal Education and the Illusion of Inclusion

Shaun Ossei-Owusu

Shaun Ossei-Owusu

Presidential Assistant Professor of Law

University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School

A new semester and a potentially new political landscape are upon us. Last month law students around the country resumed coursework. Their educational pursuits are virtual, in-person, or some mix of both. No matter the format, law students continue their educational journey in an ideologically polarized pandemic society where race, class, and gender disparities are on sharp display.

Students will also be learning in a context where changes in our legal system may have direct relevance to their legal education. As is typically the case, a newly constituted Supreme Court has a diverse docket this term that might shape substantive areas of law that students take courses in, chiefly constitutional law. There will be regulatory shifts that come with new administrations. These kinds of changes will have meaning for administrative law and related areas of law: health law, environmental law, employment law, and civil rights, to name a few. COVID-19 has upended state and federal judiciary systems in ways that have still-undetermined implications for procedural courses law students take (e.g., evidence, civil procedure, criminal procedure) and access to justice issues more generally. And we know from the late Deborah Rhode’s work which communities access to justice issues tend to devastate—racial minorities, women, and other marginalized populations.

Notwithstanding future uncertainty, one thing can be said with some measure of confidence: issues of race and gender—amongst other social categories—will remain relevant inside and outside the sometimes intellectually-cordoned off walls of law schools. How these issues are integrated in the classroom, if they are at all, will affect the substantive learning of law and will either include or exclude historically marginalized groups.

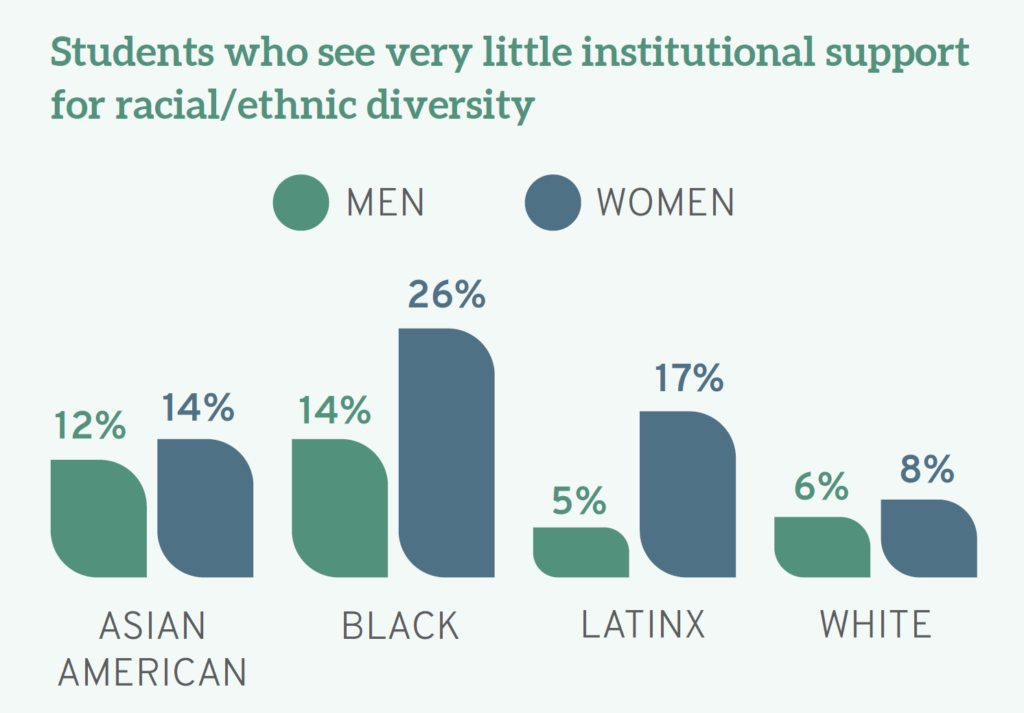

In the specific context of legal education, the results of Law School Survey of Student Engagement’s (LSSSE) Annual Survey illuminate. The Report provides a glimpse into how law schools fail to meet the aspirational goal of inclusion that often takes up primetime real estate on their websites and promotional materials. From my own read, the most jaw-dropping finding is intersectional in nature and about Black and Latinx women law students—aspiring attorneys who are often told that they do not look like lawyers when they transition to practice. 26% of Black women respondents and 17% of Latinx women respondents reported that their schools do “very little” to support racial and ethnic diversity.

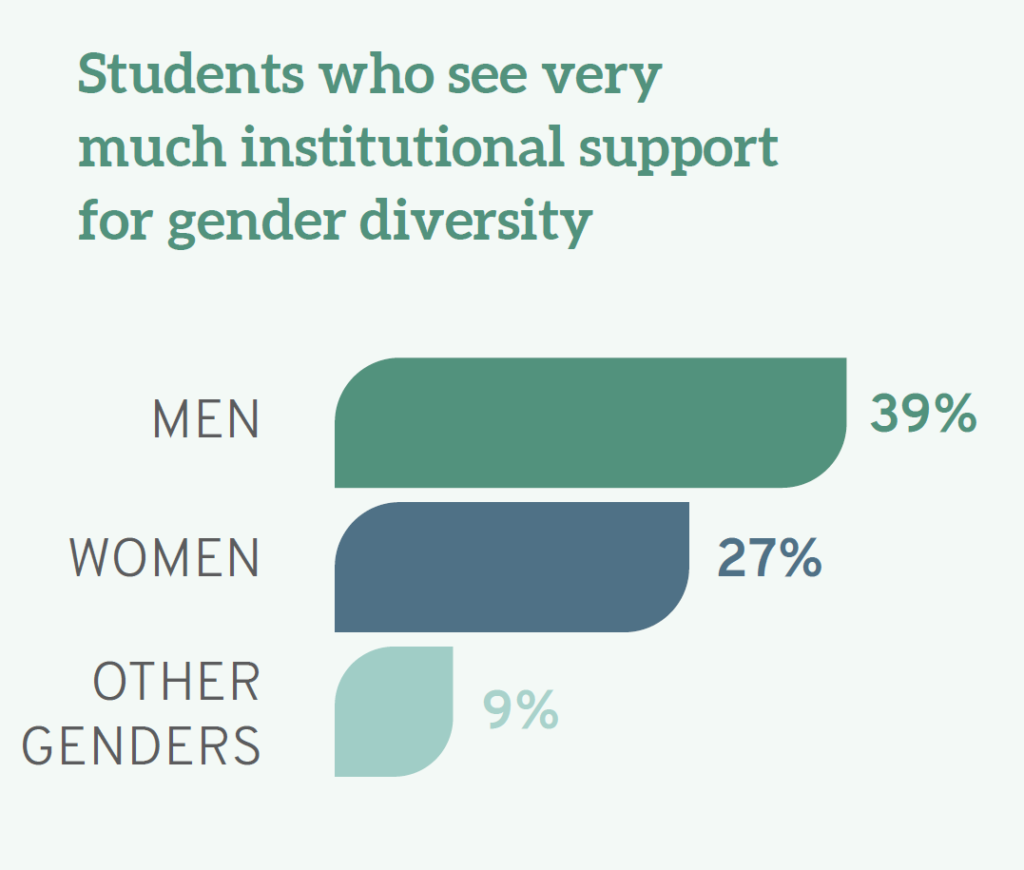

Disenchantment with the lack of support for diversity can be distilled even further. The Report notes that men varied on the issue of gender inclusivity, with 39% “very much” believing that their schools support gender diversity compared to 27% of women and 9% of individuals who identified with the “other gender” category.

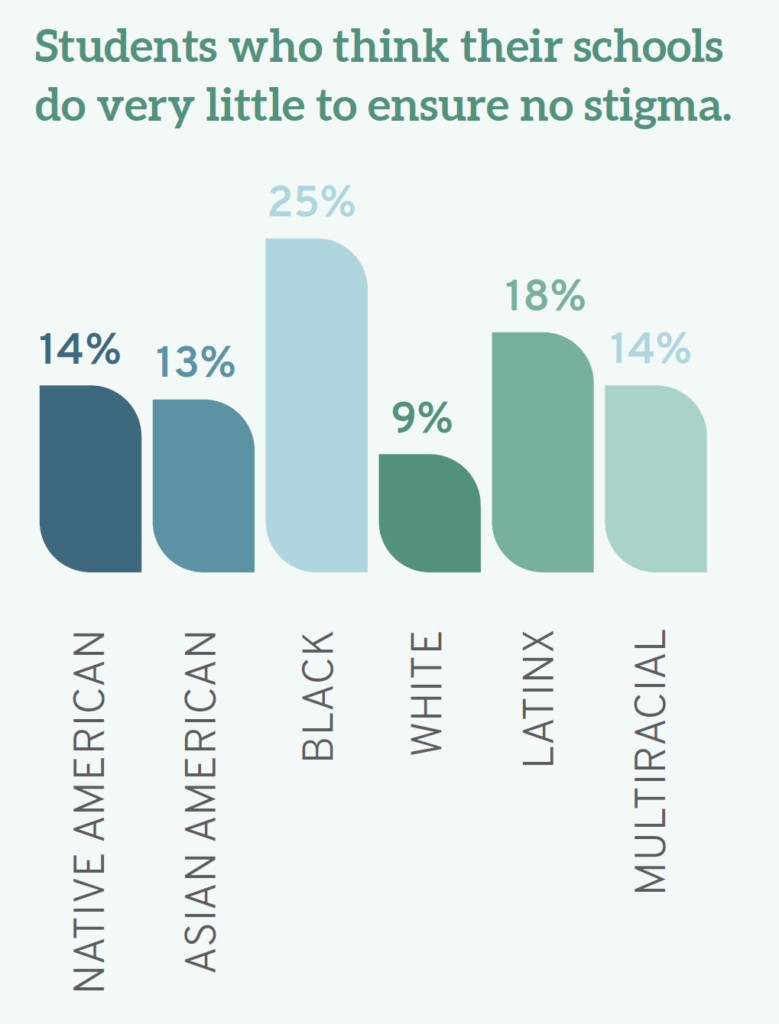

In the context of race, student views also differed, with 9% of White students, 14% of Native American students, 18% of Latinx students, and 25% of Black students believing that their schools do “very little” to ensure that students are not stigmatized based on identity.

Where sexuality and sexual orientation are concerned, 11% of heterosexual students think their schools do only “very little” to avoid identity-based stigma; conversely, 20% of gay students, 16% of lesbian students, 15% of bisexual students, and 19% of those who identify as another sexual orientation see their schools as doing “very little” in this regard. What do these findings mean for legal education and the political moment I gestured to in the beginning?

LSSSE’s data suggest that some students are dissatisfied with the six-figure education they are receiving. Put plainly, law students from backgrounds that the profession has historically excluded—women, racial minorities, LGBTQ communities, and people with disabilities in particular—do not feel part of the academic community and believe law schools are relatively disinterested in their stigmatization. In some ways, this is unsurprising, as there is a deep scholarly literature and genre of books on student disappointment with law school. Moreover, student disenchantment with legal education—which has a history of exclusion that traces back to the nativism and anti-Semitism of the early twentieth century—may in some ways be pre-determined.

The confines of the classroom, which is one of the many areas the LSSSE survey discusses, provides more insight into the inclusion-exclusion dyad. From the vantage point of some educators, law school is simply about training people to be lawyers. The most generous reading of this position suggests that social justice-like ideas like “inclusion” are too ideologically weighty to meaningfully bring in the classroom. For people who subscribe to this view, attempts at inclusion can create impossible-to-navigate landmines for professors. More skeptically, some see inclusion as an ancillary. Read in this light, the primary goal is to inculcate legal knowledge. For these professors, some things are not relevant to the practice of law and are therefore not relevant to legal education.

Such professional school-based views of legal education, vary in their reasonableness, but are held by swaths of the professoriate. Yet, there is a two-fold problem, and this is where the LSSSE survey is especially useful. First, this vision of legal education rubs up quite abrasively against the representations of law schools as bastions of inclusion. Second, this version of education, in some ways, undermines the well-touted “diversity rationale” in affirmative action jurisprudence. What does diversity mean when the subjects of diversity feel alienated?

Considering the mismatch between some students’ experiences and the stricter professional school model of legal education that some professors are beholden to, there are some options. Educators can simply be more intellectually honest about the reality that law school is a site of professionalization where inclusion principles can be trivialized. Alternatively, law schools can continue to disingenuously hitch the law school wagon to social justice rhetoric while failing to actualize inclusion as a practice. Or, in the most courageous and imaginative versions of themselves, law schools can refashion their curriculum and use developments in the legal world as opportunities to offer more inclusive learning environments.

For law schools committed to the third way, resources abound. Complaints about the need to diversify the content of law school courses have existed for decades. Scholars such as Derrick Bell and Dorothy Brown have authored casebooks that describe how race intersects with different areas of the legal curriculum, whereas feminist legal theorists, poverty researchers, scholars of law and sexuality have penned their own books, supplements, and articles that all give educational guidance on how to bring these issues into core courses, and do so in ways that are doctrinally sound. Still, some professors—many of whom have the most analytically sharp minds on their university campuses—throw their hands up in despair or continue with the same regularly scheduled program. For some of these instructors, these conversations were absent in their legal education, and they were likely not trained to incorporate these issues. Some may think it would be better to leave this work of thematic inclusion to their more expert colleagues (e.g., scholars of race, sex, class, disability) rather than wade into territory where they are sure to mess up. But throwing one's hands up in despair is increasingly a less credible course of action. The pandemic, along with the protests of 2020, have forced some people to rethink how they deliver course content, and more importantly, have made inequality a more prominent theme in our public discourse. The current socio-political moment, and the reality of pandemic pedagogy, call for curricular redesign.

Fortunately, the tools to make the classroom more inclusive are available and they are not limited to the usual courses. To be sure, law professors have written about how first-year courses like criminal law and property are inattentive to inequality in ways that produce the responses found in the LSSSE survey and have offered suggestions on how those same courses could easily be improved. But attempts to diversify and create a more inclusive curriculum are not confined to these foreseeable areas of law but can be found in more unsuspecting places like evidence, corporate law, trust and estates, and intellectual property, to name a few.

Law professors have also identified space in the curriculum for trans-substantive engagement with the kinds of questions and perspectives that demonstrate an awareness of inequality, both in legal education and in law more generally. Indeed, I, along with my colleague Karen Tani, have taken on the task of trying to simultaneously create an inclusive learning environment that rigorously addresses inequality by creating a 50-person Law and Inequality course at Penn Law. This endeavor and more meaningful engagements with diversity need not be limited to women, racial minorities, and sexual minorities. Inclusion also implicates and has meaning for the larger law student population. One of the most understated findings in the LSSSE Report is that 16 percent of white students believed law schools placed “very little” emphasis on issues of equity and privilege and do not prioritize providing students with the skills necessary to confront discrimination and harassment.

My purpose here is not to proselytize teaching a course like the one we are offering. Instead, I want to highlight how student dissatisfaction with inclusion, which the Report highlights in detailed and accessible fashion, can be situated within this critical juncture. 2021 is a unique moment where law schools can reimagine legal education in real time, and for a post-pandemic world. This will not be easy, as this is a stressful time for faculty—some of whom are in high-risk groups during the pandemic and/or have a variety of care obligations. COVID-19 has upended a lot of assumptions and forced people to change longstanding pedagogical practices. Institutions could do a lot of good by encouraging faculty reflection and supporting creative reorganization of current courses.

The LSSSE Report tells us that in many ways, law schools are failing to provide the inclusive educational spaces that they, I believe in good faith, want to offer and that students of various backgrounds actively desire. Ultimately, the teaching tools are available, the moment is ripe, and the only outstanding question is whether legal educators will make the changes necessary so that the next LSSSE survey offers more optimistic findings.