Meaningful Sources of Career Advice for Law Students

Navigating career decisions can be one of the most challenging aspects of law school, and many students find themselves seeking advice to chart their path forward. Whether considering judicial clerkships, corporate law roles, public interest positions, or alternative legal careers, law students often feel a mix of excitement and uncertainty. Balancing academic demands with the pressure to make strategic choices about internships, networking, and future goals requires careful planning. And the guidance of mentors, professors, and peers can make all the difference.

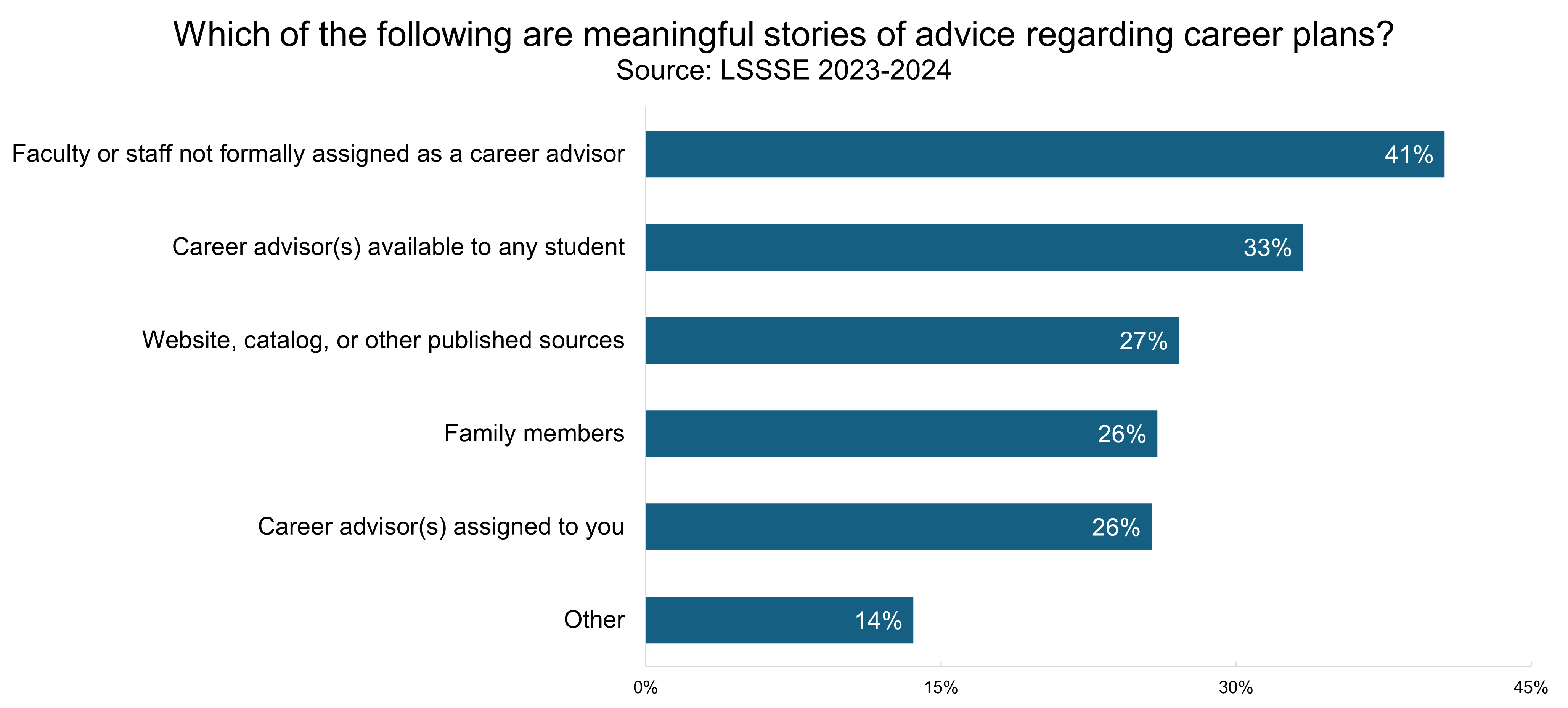

Using 2023-2024 data from the LSSSE Student Services module, we examined the meaningful sources of career advice that law students draw upon to help with professional preparation. Interestingly, law students are more likely to seek out career advice from faculty or staff members not formally assigned as career advisors rather than from formal career advisors at their law school. Only about a third of law students receive meaningful advice from careers advisors available to any student, and only about a quarter receive meaningful advice from a career advisor assigned to them, which is equal to the percentage of students receiving meaningful advice from family members (26%).

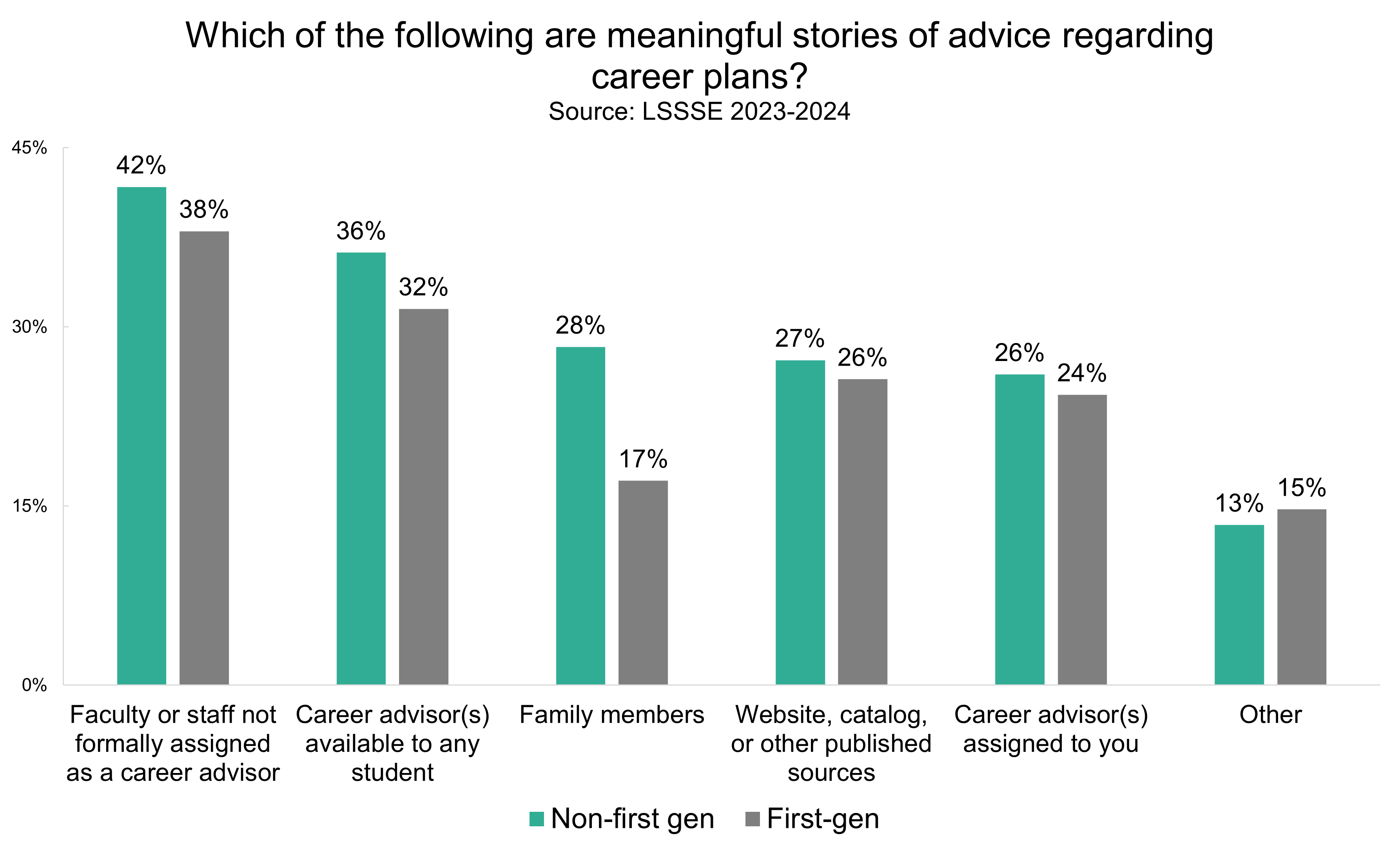

Given that family input will vary widely across different student backgrounds, we compared the sources of career advice for first-generation and non-first-generation law students. For first-generation law students (those who do not have a parent with at least a bachelor's degree), family members are much less likely to be a meaningful source of career advice. However, troublingly, first-generation students are also less likely to receive meaningful career advice from other sources relative to their non-first-generation peers. In other words, law schools may not be filling the gaps for first-generation students to support their transition into the legal profession.

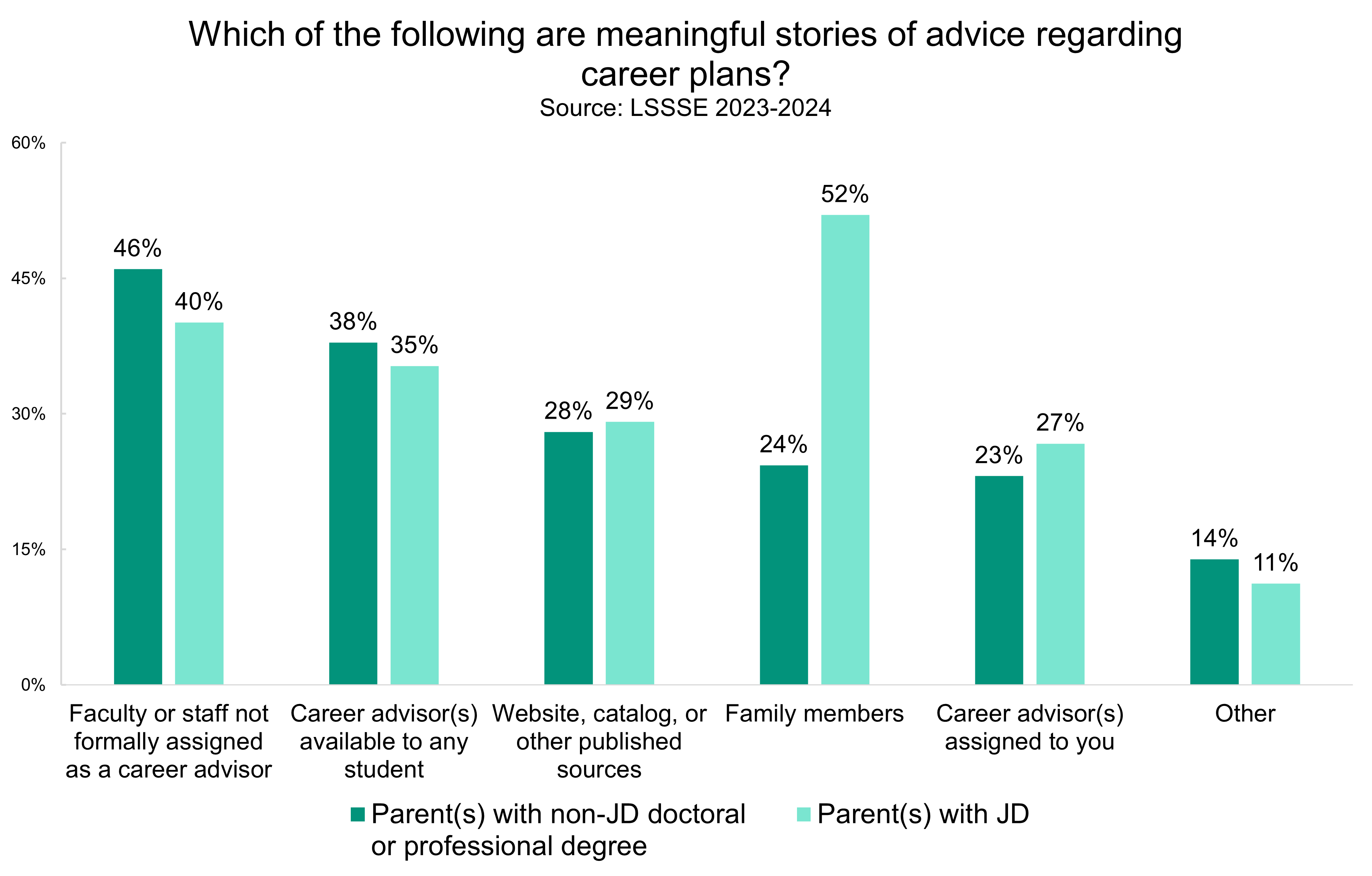

Digging deeper into the non-first-generation data, we wanted to know what impact having a parent with a law degree has on students’ sources of meaningful career advice. Among students who have a parent with a doctoral or professional degree, we see, not surprisingly, that students who have a parent with a JD are more likely to cite family members as a meaningful source of career advice than students who have a parent with a non-JD doctoral or professional degree. However, only around half (52%) of law students who have a parent with a JD note that they are receiving meaningful career advice from a family member. The students with a JD-holding parent are a little more likely to get advice from career advisors assigned to them and a little less likely to receive advice from faculty, staff, or career advisors who are not formally assigned to them.

These findings highlight critical gaps and opportunities in how law schools support students in their career preparation. While informal networks and personal relationships with faculty or staff often play a vital role, the data suggest that formal career advising structures may not be as effective as they could be, particularly for first-generation students. Law schools should consider rethinking how they engage with students in career advising, ensuring that resources are accessible and tailored to meet the diverse needs of their student body. By strengthening these systems and bridging the advice gap, particularly for those from underrepresented backgrounds, law schools can better prepare all students for the challenges and opportunities of the legal profession.

Focus on First-Generation Students, Part 2

In our last post, we shared some of the demographic characteristics of first-gen law students, which we define as law students who do not have at least one parent with a bachelor’s degree. In this post, we will dig deeper into the first-gen law student experience and how it differs from the experiences of non-first-gen law students.

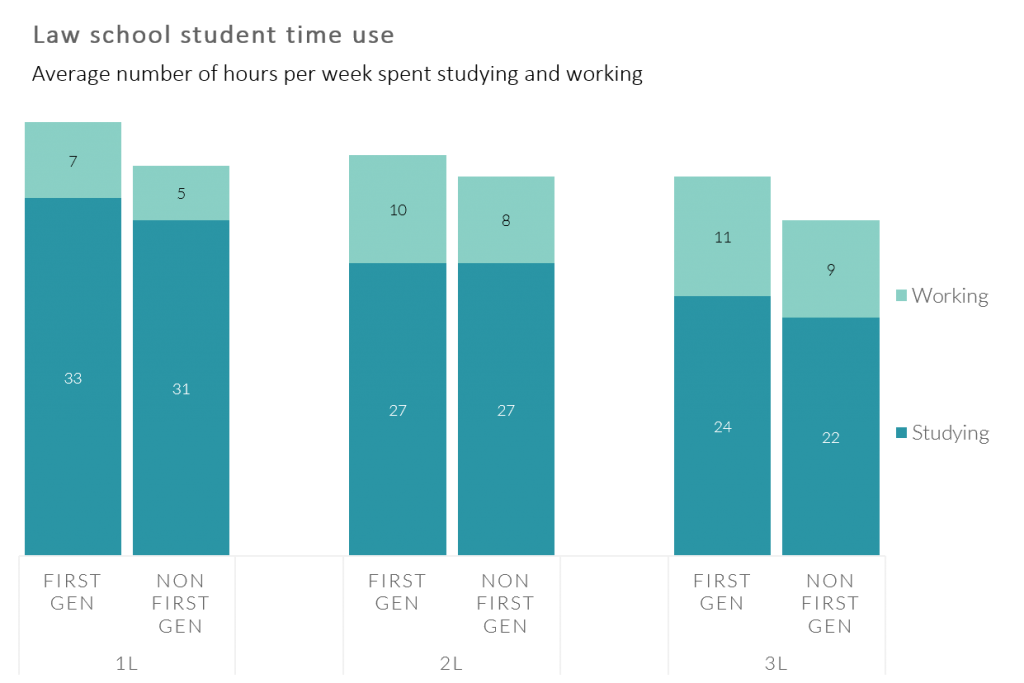

Time Usage

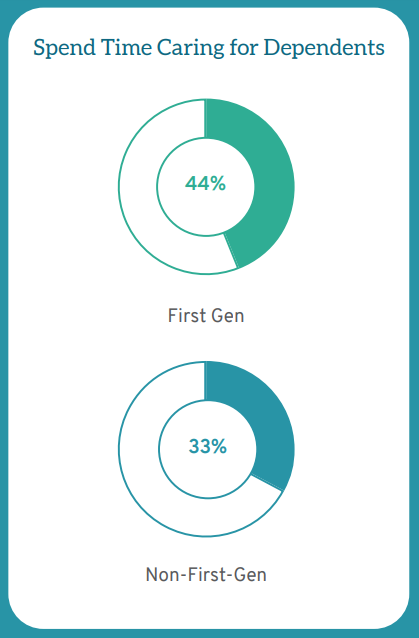

LSSSE asks students to estimate the average number of hours they spend each week engaging in activities that are directly and indirectly related to the educational experience. Time usage is important because it reflects students’ academic engagement and overall priorities. First-gen students are more likely to attend law school part-time, which suggests that they have complicated schedules with competing demands, rather than a sole focus on law school. LSSSE data show that high percentages of first-gen students have familial obligations as caretakers for dependents living in their household. Forty-four percent (44%) of first-gen students spend time caring for dependents, compared to 33% of non-first-gen students.

First-gen students are just as engaged as their non-first-gen peers in academic pursuits outside of class, despite the fact that they have more responsibilities competing for their time. First-gen students work with students and faculty on group projects at equal or greater levels relative to non-first-gen students. Roughly equal percentages of first-gen students (19%) and non-first-gen students (18%) report that they frequently work with faculty members on activities other than coursework (including committees, orientation, student life activities, etc.). Likewise, 33% of first-gen (and 31% of non-first-gen) students frequently work with classmates outside of class to prepare assignments. The diligence of first-gen students is particularly impressive given their personal obligations. One third (33%) of first-gen students always come to class fully prepared despite their family duties and work schedules, the same percentage as non-first-gen students (who tend to work less and have fewer familial obligations).

Satisfaction

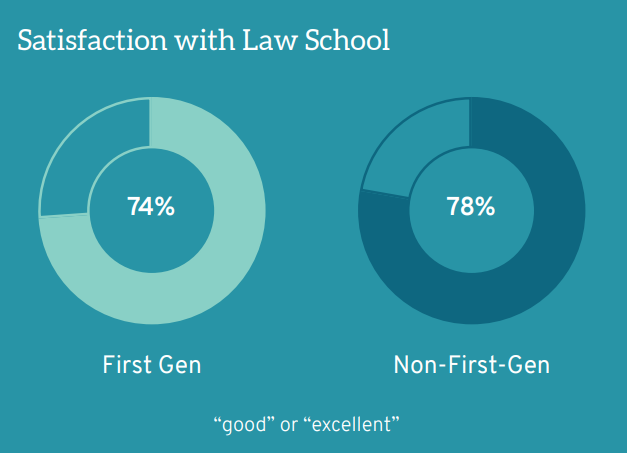

First-gen students, like law students overall, are overwhelmingly satisfied with their law school experience. Seventy-four percent (74%) of first-gen students evaluate the educational experience at their law school as “good” or “excellent,” similar to non-first-gen students (78%). Furthermore, 77% of first-gen (and 79% of non-first-gen) students report they would choose to attend the same law school again, with the benefit of hindsight. These trends are particularly noteworthy given the increased financial risks and other sacrifices made by first-gen students to attend law school.

First-gen students face unique challenges and responsibilities as they navigate legal education. Law schools should take the findings from this Annual Report, as well as their own school-specific LSSSE data, to craft targeted programs to support first-gen students. Better supporting them personally will free up time and resources for first-gen students to devote to not only academics, but other co-curricular pursuits so they are optimally placed to thrive as they enter the legal profession.

Focus on First-Generation Students, Part 1

Our next two blog posts will provide selected snippets from the LSSSE 2024 Annual Report: Focus on First-Generation Students. To read the entire report, please visit our website.

First-Gen Demographics

First-generation (first-gen) students are trailblazers for their families. They attend college without the guidance of a parent who has completed their own bachelor’s degree. Decades of research show that first-gen students overcome significant challenges simply to gain access to college and invest even more to persist until degree completion. First-gen students tend to enter higher education with fewer financial resources and less social and cultural capital than those who have at least one parent who completed a college degree. Although first-gen students have already drawn on their resiliency and determination to adapt to college life, law school brings its own cultural norms and ways of learning that are, again, likely to be unfamiliar.

Despite these expected challenges, few studies focus on the experiences of first-gen students in law school. In 2014, LSSSE was one of the first organizations in legal education to collect data on first-gen students by adding a survey question about parental education. The data LSSSE has collected shed light on how first-gen students engage with law school and how their experiences differ from those of their non-first-gen classmates.

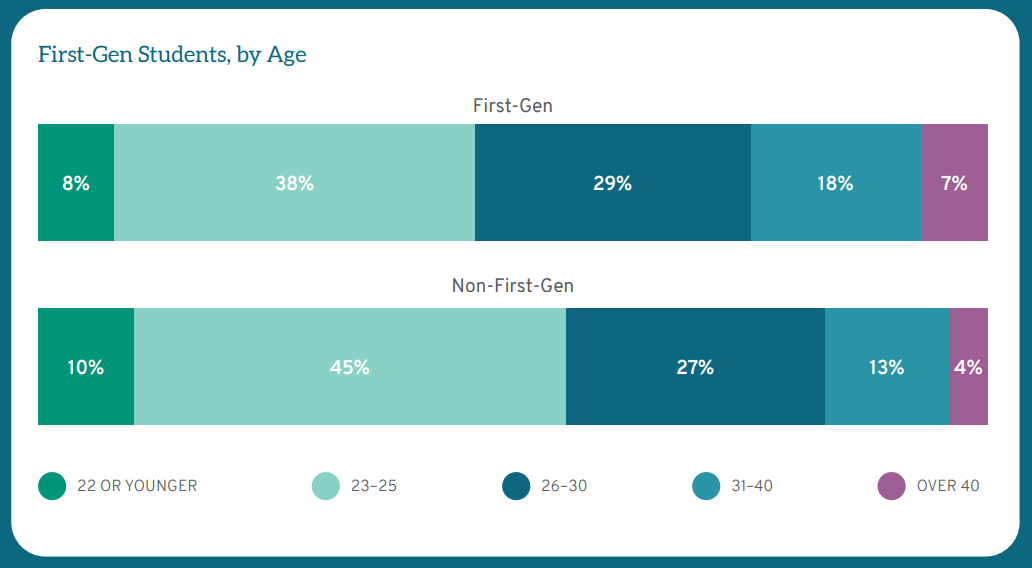

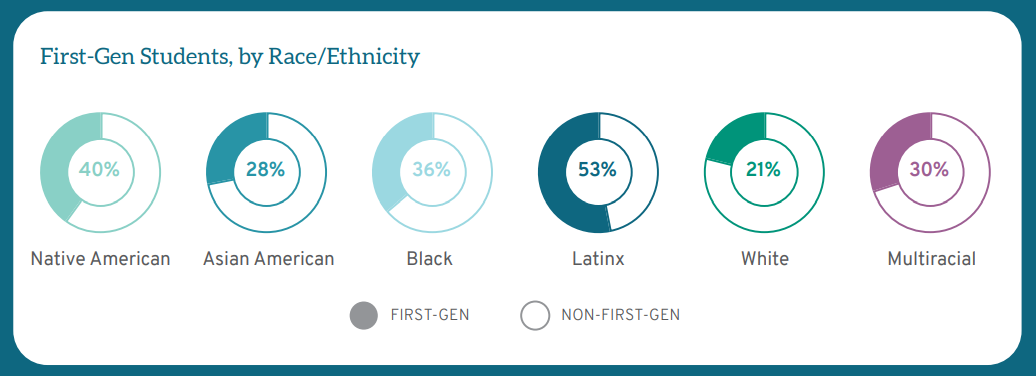

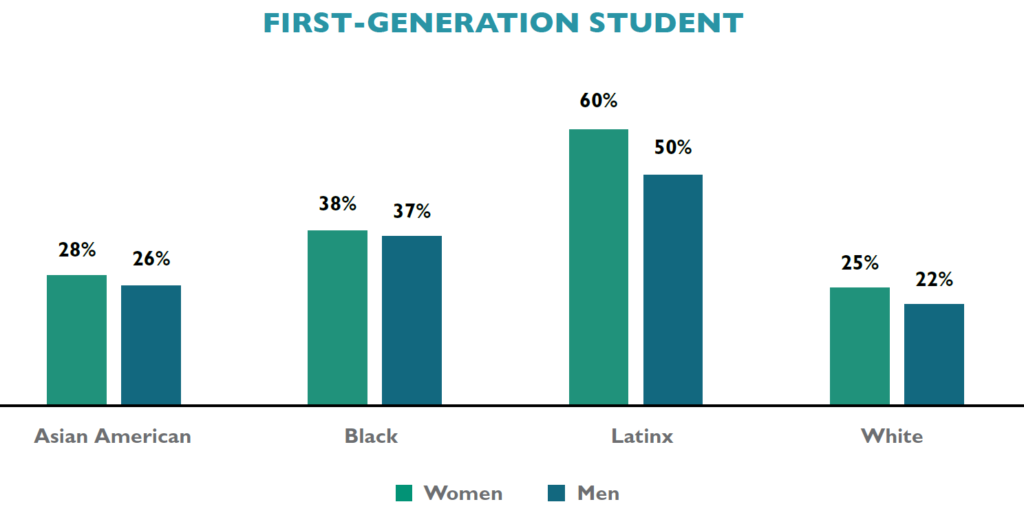

For LSSSE analyses, students who respond that neither parent received a bachelor’s degree or higher are considered first-gen students. First-gen students comprise over one-quarter (26%) of the LSSSE respondents. First-gen students tend to be different from non-first-gen students in important ways, including race, gender, age, and a full-time focus on law school. Students of color from every racial group are more likely than White students to be first-gen. For instance, 53% of Latinx respondents and 36% of Black respondents are first-gen, compared with 21% of White respondents. Twenty-eight percent (28%) of women are first-gen students compared to 24% of men. First-gen students also tend to be older, with 54% of first-gen students being over the age of 25 compared to 44% of non-first-gen students. Finally, while the vast majority of law students in the U.S. study on a full-time basis, first-gen students are more likely to study part-time by about 10 percentage points. Thus, in addition to their first-gen status, many of these students have other demographic differences from the average law student.

First-Gen Student Debt

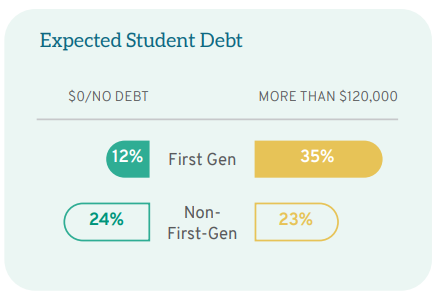

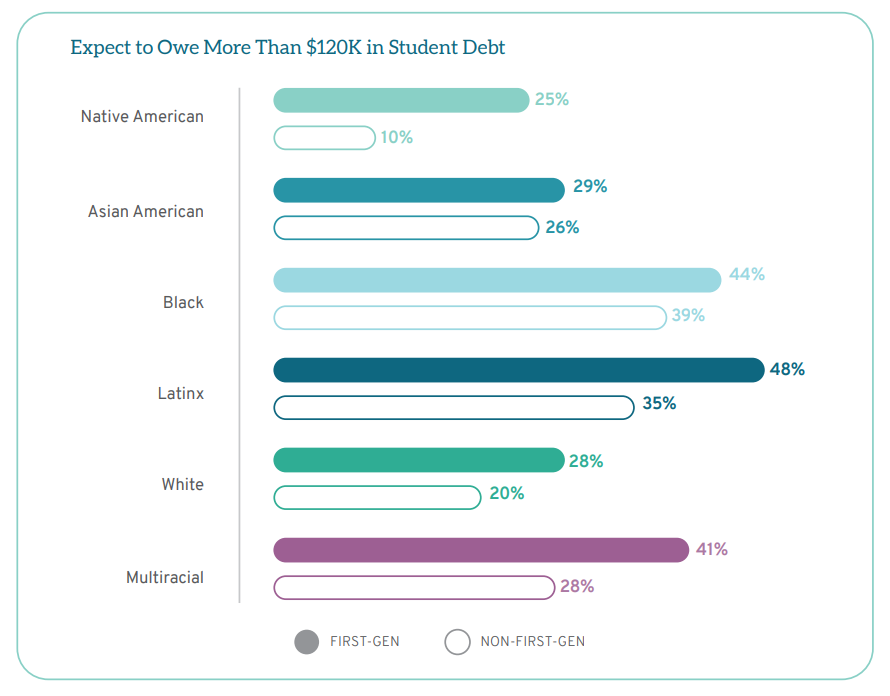

Parental education is often used as a proxy for socioeconomic status. A college degree has a significant positive impact on salary and career earnings over a lifetime. On average, first-gen students come from families that earn less than the families of students with a parent who completed college. Because first-gen students enter law school with lower undergraduate GPA and LSAT scores and because higher LSAT scores result in greater success with scholarships, first-gen students are less likely to be awarded merit scholarships in law school. As a result, first-gen students rely on student loans to a greater extent than their classmates. For instance, 24% of non-first-gen students anticipate graduating with no law school debt compared to only 12% of first-gen students. Conversely, roughly one-quarter (23%) of non-first-gen students expect to graduate with more than $120,000 in student debt compared to over one-third (35%) of first-gen students. Students from the same racial background nevertheless have significant debt differentials based on whether they are first-gen students, with first-gen students of color borrowing at particularly high levels.

First-gen students differ from their non-first-gen classmates in meaningful ways. First-gen students typically are older students, many have caretaking responsibilities, and they are more likely to come from families with fewer financial resources, necessitating working while in school. Because of these differences, first-gen students bring valuable life experiences and diverse perspectives to classroom conversations. Once they complete law school, they are also equipped to bring the fruits of their legal education back to their communities. The hard work and determination that first-gen students bring to law school is nonetheless coupled with higher levels of debt than their non-first-generation peers. This creates an additional burden not only during law school but as they choose their first jobs as lawyers and continue their legal careers.

In our next blog post, we will examine how first-gen law students use their time and the degree to which they engage with different aspects of the law school experience.

Guest Post: The Importance of Supporting First-Generation Law Students

Melissa A. Hale

Melissa A. Hale

Director of Learning for Legal Education

Law School Admission Council

Today is First-Generation Student Day[1]! So, to celebrate, I want to talk about why we should support first-generation law students, and how we can do that.

Who are first-gen students? Although definitions vary and self-identification is important, a first-generation student is typically one whose parents or legal guardians have not completed bachelor’s degrees [2]. First-generation students are an important part of diversity, equity, and inclusion. However these students are often overlooked when discussing DEI goals. In fact, when I started law school[3], I’m not even sure the term “first-generation student” was being used, or if it was in some circles, students certainly weren’t recognizing the term or identifying as “first-gen” the way they are now.

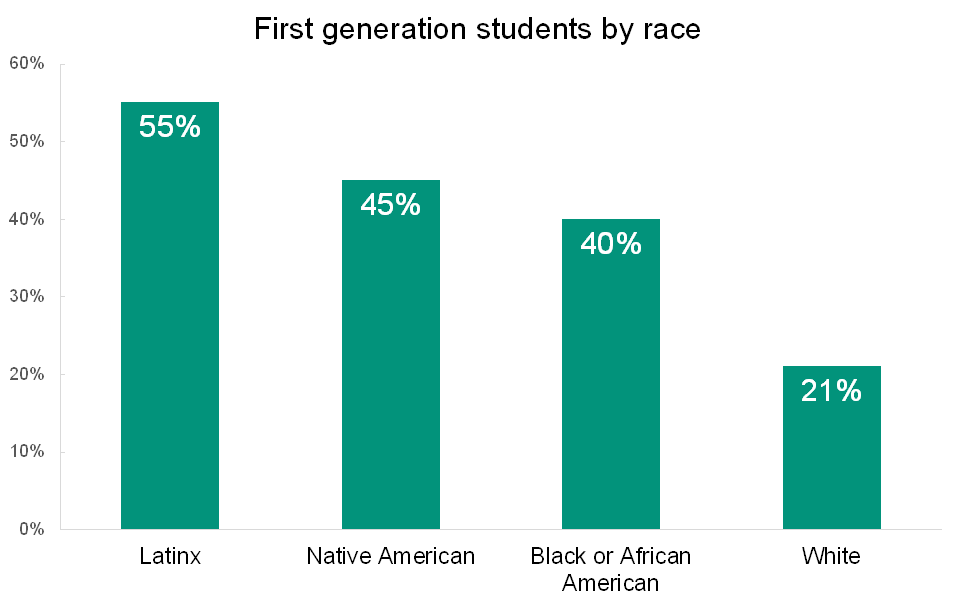

It’s certainly progress that we, as educators and researchers, are recognizing this group of students, but that’s not enough. We need to do more. Especially because there is significant intersectionality between first-generation students and historically underrepresented BIPOC students, including students of color and students from a lower socioeconomic status. According to the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE), 29% of law students are first-generation. Students of color are more likely than their white classmates to be first-generation. More than half of all Latinx students, 45% of Native American students, and 40% of Black or African American students are first-generation.

What Makes First-Generation Students Different?

So why does this matter and why is this group different? Well, first-generation law students often come to law school with fewer resources than their peers, including a lack of social capital. Most importantly, they also come to law school bearing an “achievement gap.” The “achievement gap” refers to the disparity in academic performance – grades, standardized-test scores, dropout rates, college-completion rates, even course selection and long-term success– between groups of students. In this instance, we are referring to the gap between students who have had parents complete some form of higher education (“continuing-generation students”) and those that have not. The Close the Gap Foundation refers to this as “the opportunity gap” instead of the achievement gap, and specifically states that it is “the way that uncontrollable life factors like race, language, economic, and family situations can contribute to lower rates of success in educational achievement, career prospects, and other life aspirations.”[4]

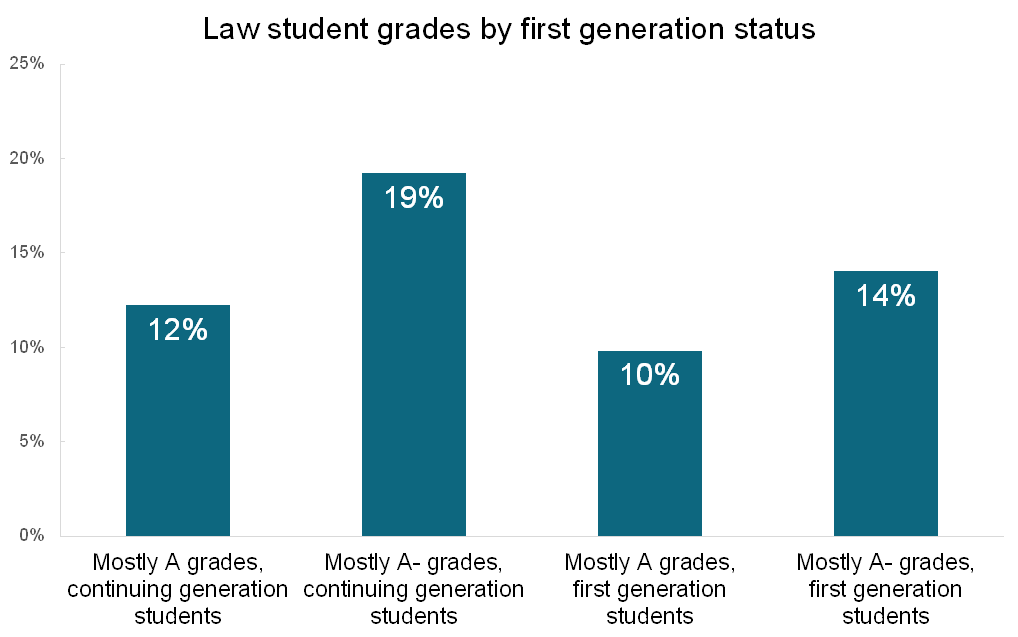

This gap becomes obvious when you look at the data. In the 2021 LSSSE survey, 31% of continuing generation students earned a A- or higher. For first-generation students that number was only 24%. While this might not seem like a staggering gap, without networking and family connections, first-generation students have to rely more heavily on grades for job prospects, so that gap can make a significant difference to their future.[5]

As for social capital, in all professions and cultures there are unwritten rules and norms, generally learned from observing others or knowing people in the culture or profession. Essentially these are not rules you learn about in any explicit way. There is no way for students to study up on these rules, no matter how diligent or well-prepared they are, because they are acquired only through experience. While incoming law students start to pick up on some of these rules during their undergraduate programs, there are still huge gaps where law school and the legal profession are concerned.

Finally, it is far more likely that first-generation students will be providing care for a dependent, either a parent or a child. In fact, 11.3% of first-generation students care for a dependent more than 35 hours per week, as compared to only 5.2% of continuing-generation students.[6] In addition, first-generation students typically end up working more hours, either in legal or non-legal jobs, than their continuing-generation counterparts.

Taken all together, this means that most first-generation students come to law school with considerable hurdles: lower access to finances, lower social capital (i.e., fewer networking connections), lack of exposure to professional norms, and finally, hurdles related to academic preparation, especially when so much of the language used in law school might be brand new to them. And first-generation students themselves know this, coming to law school with concerns surrounding academic success, their career path, building a professional network, finances and family obligations.[7]

What Can We Do?

As legal educators we can do so much. And this starts at the point of admissions. Today, I’m speaking on a panel at LexCon ’22[8] called "Empowering First-Gen Students Through Your Schools' 'Hidden Curriculum,'" along with Morgan Cutright of AccessLex, Teria Thornton, and Susan Landrum, Dean of Students at Illinois College of Law.

Our panel is discussing ways to support first-generation students through the admissions process, navigating financial aid, and finally with academic support once they enter law school. The first step is having these discussions because we often don’t realize the challenges that first-generation students face or what resources they might lack. This is an opportunity for student facing law school professionals – student services, academic support, financial aid, admissions, career services and other administrators – to think through what information we take for granted and then how to make the transition for students a bit easier and more welcoming. For example, even recognizing that many choices they make might be based around financial considerations and scholarships, or staying close to family. Or that purchasing books so that they can read the first class assignment might prove difficult if financial aid checks aren’t distributed before classes begin. Another challenge might be career services assuming that all students have interview appropriate clothes to wear, or can afford such clothes. Some schools have set up interviewing closets where professors and alumni donate old suits for students.

Beyond conversation, at the point of admission, schools can also provide students with a wealth of resources that will help them feel like they belong in law school, and reinforce the message that law school is difficult for all -- not just them. We know that a sense of belonging is linked to positive academic outcomes, such as increased engagement, intent to persist, and achievement[9] However, first-generation students report less belonging, which then increases the achievement gap mentioned above. In addition, students who don’t feel they belong also find it much more difficult to persist in the face of struggle, or even reach out for assistance.

As an example of how we can address a sense of lack of belonging, I used to send incoming students a “law school glossary” upon admissions. It was fairly simple, only a few pages of common words that we tend to use. This was sent to all students, not just first-gen, because some of the terms we use on a daily basis are mystifying to anyone who is new to the study of law. For example, what is a “1L” or what on earth is “K” or “Civ pro”? Abbreviations and acronyms can be just as daunting, and alienating, as the Latin often used.

Because first-generation students often assume that everyone else knows things that they don’t, they might hesitate to ask what are perfectly reasonable questions. Providing them with a quick list of frequently used terms is a great way to decrease feelings of uncertainty. This glossary turned into a book – The First Generation’s Guide to Law School[10] – which was essentially the memo I wish I had received before I started law school. I couldn’t cover everything, but tried to cover most of the unwritten rules surrounding law school, as well as the core academic skills needed to thrive. I wanted to make sure that students could go into their first week of classes feeling confident.

In addition, there are many summer bridge programs that exist. I’m currently working on such a program for the Law School Admission Council (LSAC), and it will be available in the summer of 2023. We had a small bridge program in 2022, Law School Unmasked, and received positive feedback from students on how it increased their feelings of confidence and belonging, and generally increased their ability to succeed in their first semester.[11] For example, “It was very helpful for me as a first generation college and now law student since I do not have anyone I can turn to for help with these topics we went over. Figuring out how things work as a first generation student constantly seems like an uphill battle of asking lots of questions to lots of people who always seem to have vastly different answers and then finding out which answers are correct. This program helped to answer a lot of questions that would have made me feel lost for the first semester of law school.” This shows that programs designed for first-generation students can and do make a difference!

Finally, I encourage all schools to support the formation of a first-generation law student group. This can help ensure first-gen students feel connected, and in a very obvious way, realize they aren’t alone. When I was in law school, I assumed that I might be the only person in the building who didn’t have parents who went to college. However, when I started writing my book – and asking for stories and advice – I discovered that many of my friends and professors were, in fact, also first-generation students. This was shocking to me. So a student group, first and foremost, signals to students that they aren’t the only ones. LSAC is currently working on a National First-Generation Law Student Group, and meeting with already existing student groups to find the best ways to support and foster these types of student organizations.

If you have questions about how to support first-generation students, please feel free to reach out to me at mhale@lsac.org.

[1] Cite 3

[2] FAQ: First-Gen Definition, The Center for First-generation Success, https://firstgen.naspa.org/why-first-gen/students/are-you-a-first-generation-student.

[3] Way back in the dark ages in 2003.

[4] Close the Gap Foundation, last visited May 18th, 2022 https://www.closethegapfoundation.org/glossary/opportunity-gap?gclid=Cj0KCQjwspKUBhCvARIsAB2IYuscRgwXvBQgnHlxQtXJ34Bw4m8g4X_HdMdS_csWATPxgPN0dzuk6eUaAuwKEALw_wcB

[5] id.

[6] Law School Survey on Student Engagement, LSSSE Survey Tool 2021, https://lssse.indiana.edu/about-lssse-surveys/ 1 (Last visited Jan. 17, 2022).

[7] Id.

[8] https://web.cvent.com/event/e2323c1d-5bfb-4ab2-aad0-3cc606276ab1/summary

[9] Id.

[10] https://cali.org/books/first-generations-guide-law-school

[11] https://www.lsac.org/law-school-unmasked

Relationships with Law Faculty

Law students generally have strong relationships with law school faculty members. In 2022, 71% of LSSSE respondents ranked their relationships with faculty a 5 or higher on a 7-point scale, where 7 represents faculty who are “available, helpful, and sympathetic.” Only 12% of students ranked their relationships a 3 or lower, and a mere 1% of students ranked their relationships a 1, meaning they feel that the faculty at their law school are “unavailable, unhelpful, and unsympathetic.”

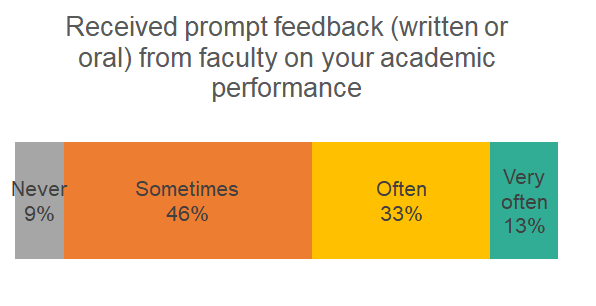

Relationships with instructors are built both inside and outside the classroom. More than half (53%) of law students discussed assignments with a faculty member often or very often, and only 5% never discussed assignments with a faculty member. After completing assignments, most law students (91%) receive prompt feedback from faculty on their academic performance at least sometimes. However, only 13% say they receive prompt feedback very often, and 9% never receive prompt feedback.

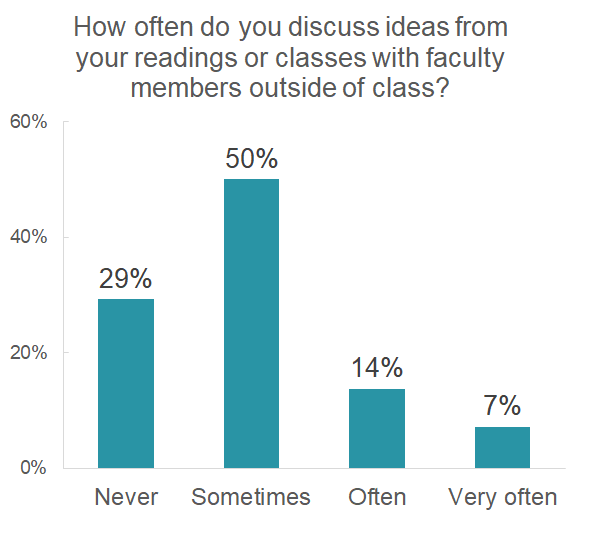

About one in five students (21%) often or very often discussed ideas from their readings or classes with faculty members outside of class, and another half (50%) did so sometimes. This practice tapers off a bit over time, with 22% of first-year students discussing ideas with faculty members outside of class often or very often compared to 19% of 3Ls and 11% of 4Ls.

Law school faculty can provide crucial guidance about navigating the legal job market, and the vast majority of students (84%) take advantage of their advice. Just over a third of students (36%) discuss their career plans or job search activities with a faculty member of advisor often or very often. Around 82% of first-generation students (neither parent holds a bachelor’s degree) have discussed their career plans with faculty compared to 85% of their non-first-generation peers.

The relationships students form during their time in law school can be crucial to their future success. The majority of law students make the most of these relationships, and they appreciate the support and knowledge they receive from the faculty of their law schools.

First Generation College Students Bear More Law School Debt

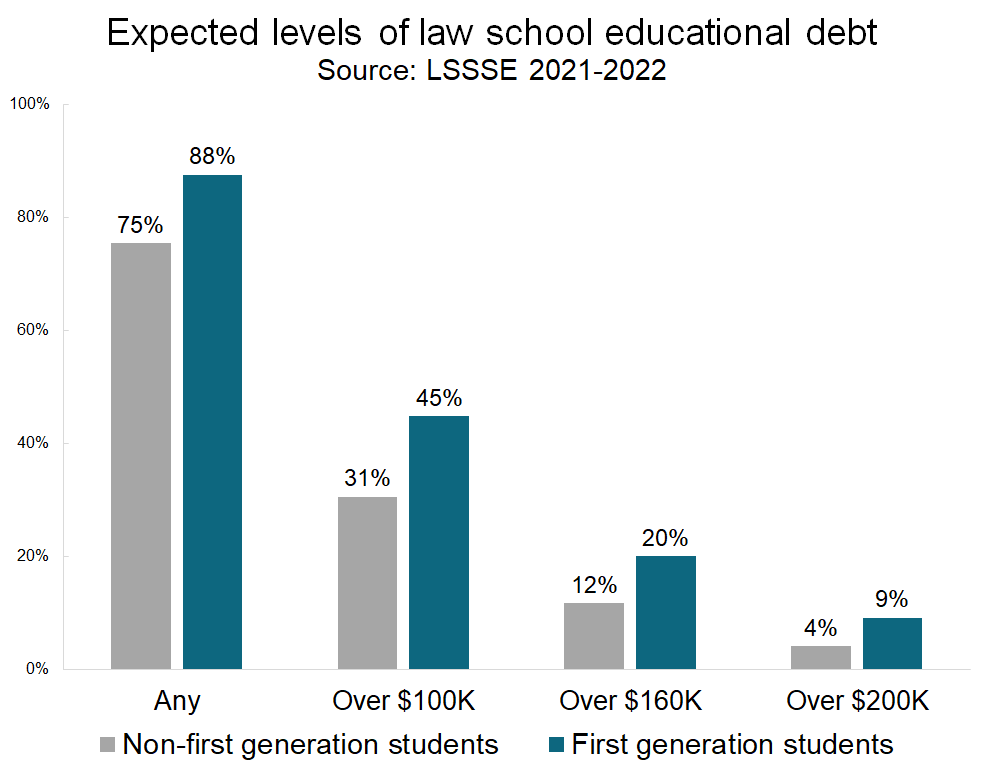

First generation law students, defined as those students who do not have at least one parent with a bachelor’s degree, face unique hurdles in higher education. In addition to navigating an unfamiliar cultural landscape, first generation students may be particularly challenged by financial concerns and student debt. In fact, although 75% of non-first generation law students expect to have some debt from attending law school, that number climbs to 88% for first generation students.

Additionally, the total dollar amount owed in student debt tends to be higher for first generation students. LSSSE 2021 and 2022 survey data show that first generation law students expected to owe an average of $96,000 compared to $71,000 for their non-first generation classmates. Around 45% of first generation students expected to owe over $100,000, but only 31% of non-first generation students expected to have loan balances that high. Shockingly, first generation students are twice as likely as their non-first generation peers to owe more than $200,000, which is the highest debt category recorded by LSSSE. Only four percent of non-first gen students fall into this category, compared to a full nine percent of first gen students.

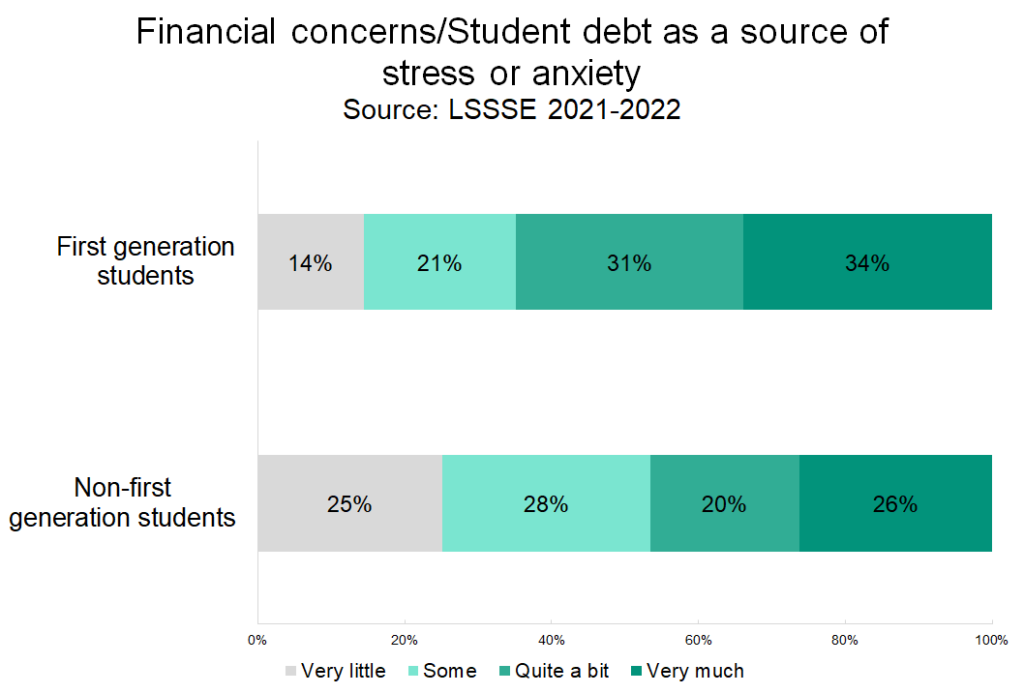

The differing financial picture for these groups of students takes an emotional toll. Although first gen and non-first gen students report similar stress levels related to law school (about 84% rank their stress a 5 or higher on a 7-point scale), two-thirds of first gen students say that financial concerns and student debt are a big source of stress or anxiety compared to less than half (46%) of non-first gen students.

Annual Results 2020 Diversity & Exclusion: Diversity Skills

This year for the first time, LSSSE introduced a set of questions focused on diversity and inclusion that supplement related questions from the primary survey. The Diversity and Inclusiveness Module examines environments, processes, and activities that reflect the engagement and validation of cultural diversity and promote greater understanding of societal differences. The 2020 LSSSE Annual Results Diversity & Exclusion report presents data about how diversity in law school can prepare students for the effective practice of law upon graduation. In our final post in this series, we will explore how law schools can teach skills to equip students to interact with people from different backgrounds.

Schools have a responsibility to not only admit and provide the resources to enroll a diverse class of students, but to impart the skills these students will need to be effective lawyers. Increasingly, the practice of law requires sensitivity to issues of race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status. Law schools can empower students first by encouraging them to reflect on their own identities, and then supplying coursework on issues of privilege, diversity, and equity; while it is important for students to learn about anti-discrimination and anti-harassment, law schools should also equip them with the tools they will need to fight these social problems as attorneys and civic leaders.

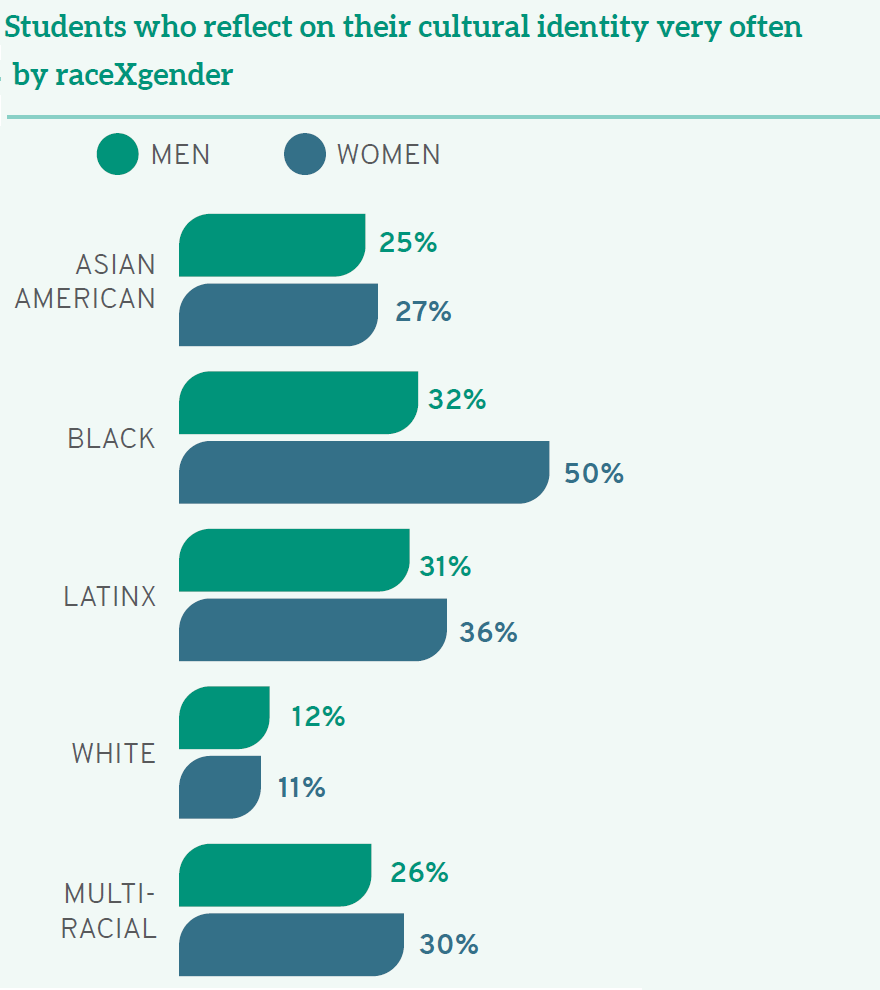

Yet schools are, by and large, not preparing law students to meet these challenges and succeed as leaders. When students were asked how frequently they reflect on their own cultural identity, only 12% of White students do so "very often," compared to 50% of Native American students, 44% of Black students, and 34% of Latinx students. Even more alarming, over a quarter (26%) of White students never reflect on their cultural identity during law school. When we consider the intersection of raceXgender, an even more troubling picture emerges. A full 28% of White men and 25% of White women in law school never reflect on their cultural identity, compared to the 50% of Black women who do so "very often."

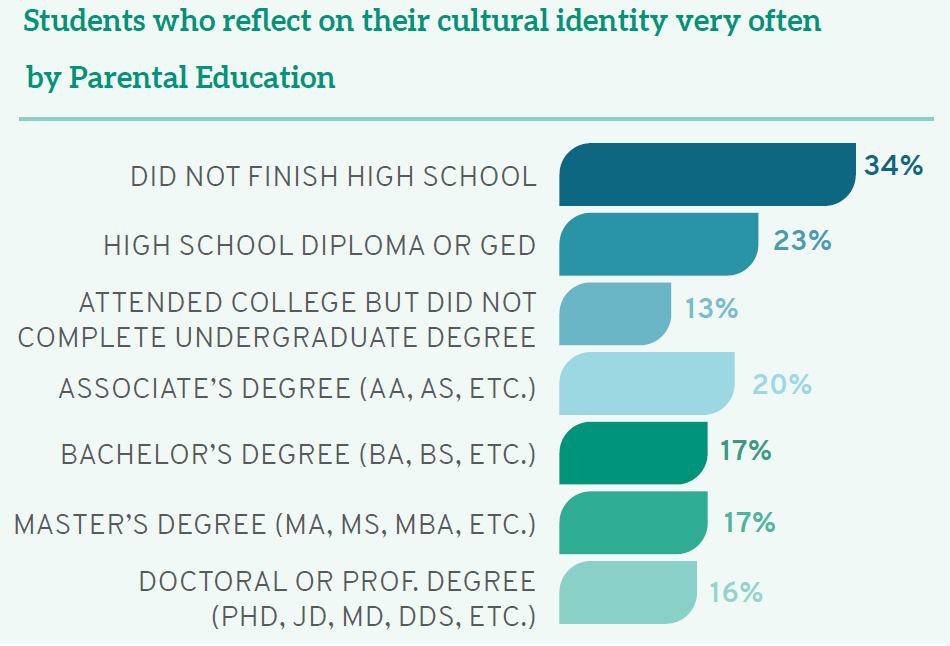

Students whose parents have less formal education are also more likely to reflect on their cultural identity, including 34% of those whose parents did not finish high school as compared to 16% of those who have a parent with a doctoral or professional degree. In sum, students with racial, gender, or class privilege are less likely to reflect on the benefits associated with their identity.

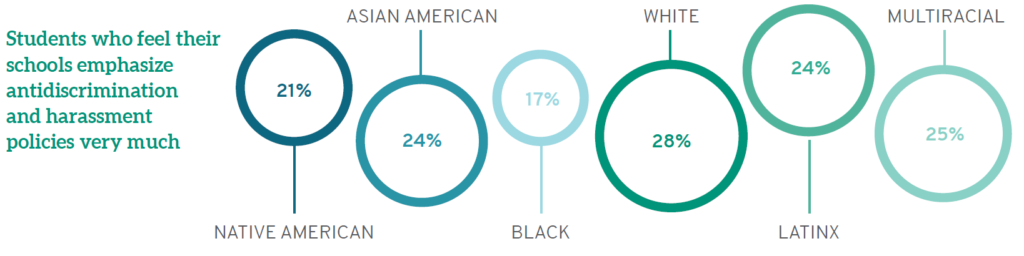

Even without self-reflection, students can nevertheless gather information about anti-discrimination and harassment policies. LSSSE data show that while White students see their schools as prioritizing this information, students of color do not agree at the same high levels. Similarly, men (31%) are more likely than women (23%) and those with another gender identity (11%) to believe their schools strongly emphasize information about anti-discrimination and harassment. Considering raceXgender, a full 27% of Black women see their schools as doing "very little" to share information on anti-discrimination and harassment, while 32% of White men believe their schools do "very much" in this regard.

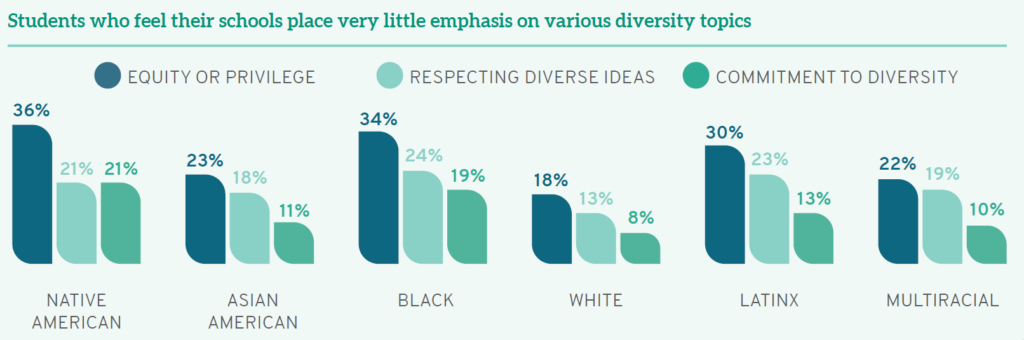

Equally troubling, students from different backgrounds perceive institutional emphasis of various diversity-related topics in starkly divergent ways. Although White students believe that their schools emphasize issues of equity or privilege, respecting the expression of diverse ideas, and a broad commitment to diversity, students of color are less likely to agree. Students of color—including those who are Black, Latinx, Asian American, Native American, and multiracial—frequently note and appreciate assignments or discussions of race/ ethnicity and other identity-related topics in the classroom; yet they are more likely than their White peers to report that schools place “very little” emphasis on diversity issues. Women are similarly more likely than men to believe their schools do “very little” to emphasize diversity in coursework. Furthermore, higher percentages of Black women report “very little” emphasis on equity or privilege (36%), respecting diverse perspectives (27%), and an institutional commitment to diversity (21%)— compared to high percentages of White men who believe their schools are doing “very much” in all three arenas (20%, 24%, and 34%, respectively). First-gen students are also more likely than their classmates whose parents completed college to note “very little” diversity coursework. Synthesizing these data, students who are traditionally underrepresented and marginalized—arguably the students who have the most personal experience with issues of diversity—see their schools as doing less to promote diversity and inclusion than those who are privileged in terms of their race/ethnicity, gender, and parental education.

As part of a broad curriculum that sets up students for their future practice, law schools should teach students diversity skills—a set of skills that facilitate success in our increasingly globalized society, ranging from personal reflection to the tangible tools lawyers can use to combat discrimination. Law schools that succeed at these diversity-related endeavors will be preparing our nation’s newest lawyers to meet the full range of challenges ahead.

LSSSE Annual Results 2019: The Cost of Women’s Success (Part 2)

Contextualizing Women’s Success

Women’s relative success in law school is quite significant when we consider basic demographic differences between women and men when they first enroll in law school. Fewer economic resources and lower test scores do not seem to inhibit women from achieving at high levels once on campus.

Parental education is a common proxy not only for family income but for future educational success, with the children of highly educated parents generally drawing on class privilege and extra resources to achieve at high levels. LSSSE data reveal that women are more likely than men to be first-generation law students, with 30% reporting that neither parent holds a bachelor’s degree as compared to 25% of male law students. This finding is consistent for women regardless of race/ethnicity, with Asian American, Black, Latinx, and White women being more likely than men from those same backgrounds to be the children of parents who did not earn at least a college degree.

Even considering those whose parents are highly educated, women law students are less likely than men to have a parent who is a lawyer. Among those reporting that they have a parent who earned a doctoral or professional degree, 57% of men but only 52% of women report that their parent’s degree is a J.D. Only Asian American women are more likely than men from their same racial/ethnic background to have a parent with a law degree; higher percentages of male law students who are Black, Latinx, or White have a lawyer parent than women from those same backgrounds.

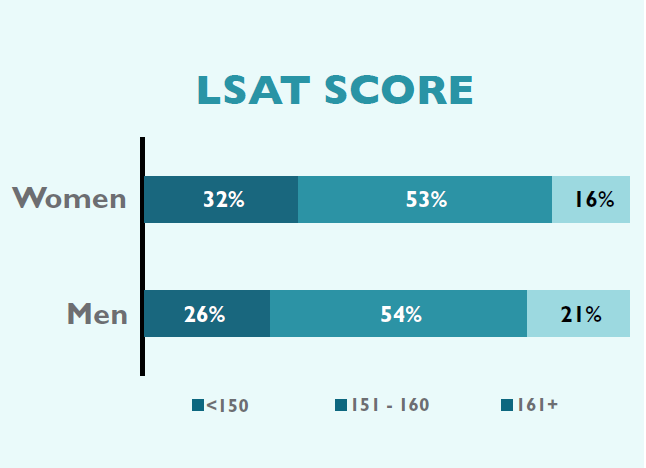

In addition to demographic differences based on parental status, women also report lower LSAT scores than men, even when comparing within racial/ethnic groups. While 21% of men report LSAT scores in the highest range of 161 or above, only 16% of women report similar achievement on this exam. This finding mirrors other critiques of high-stakes testing as potentially limiting opportunities for non-traditional students including women and people of color.

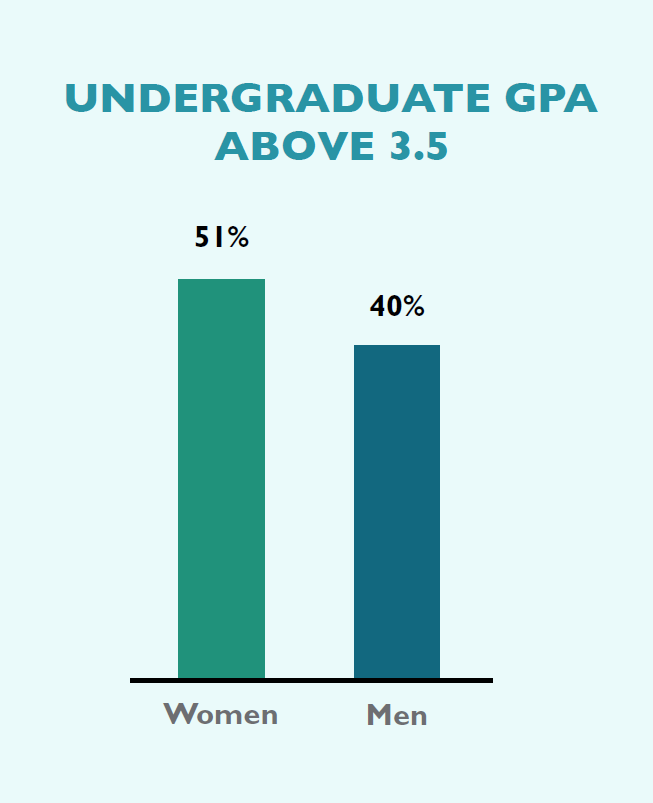

Conversely, higher percentages of women than men enter law school with undergraduate grade point averages (UGPAs) in the top range. A full 51% of women report UGPAs of 3.5 and above as compared to only 40% of their male classmates. As with LSAT scores, this gender finding is consistent across race/ethnicity: when comparing women and men from the same background, women outperform men on UGPA. Recall that in spite of the inconsistency of lower LSAT scores and higher UGPAs, women nevertheless report slightly higher overall law school grades than men. This may further bolster research questioning the value of using test performance as the primary determinant of expected success in law school and beyond.

The next post in this series will offer some opportunities for improvement in gender equity in legal education. You can read the entire LSSSE 2019 Annual Results The Cost of Women’s Success (pdf) on our website.

First Generation Law Students: Use of Time

First-generation students face a myriad of challenges in higher education. At the undergraduate level, they tend to apply to college with lower admissions indicators (e.g., grade point averages, standardized test scores) than other students, and once enrolled, they tend to persist and graduate at lower rates. The challenges faced by first-generation students have roots in academic, social, and financial realms.

The bulk of the research on first-generation students focuses on the undergraduate experience. However, very little research has been conducted on first-generation students who go on to attend law school. Therefore, the data presented in this section explores largely unexamined questions.

LSSSE 2014 data show that on a number of dimensions, the amount of time that first generation law students spent with peers and faculty outside of class was significantly less than non-first generation law students.

Co-curricular activities are critical components of the academic experience. These activities often supplement class discussions and aid in the development of new skills. They can also make students more attractive to potential employers. First-generation students reported lower rates of participation in some of the most prominent co-curricular activities, such as law journal, moot court, and faculty research assistantships. Eligibility for these activities is often determined by law school grades. Differences in time spent studying for class and working for pay could also contribute.

First-generation students reported spending about 8% more time studying for class and 25% more time working for pay, compared to other students. The disparities in time spent studying are greatest in the latter years of study. First-generation 3Ls reported spending 8.5% more time studying than other 3Ls.

Disparities in the amount of time spent working are most pronounced in the first year, when first-generation students report spending 40% more time. The actual hours spent do not seem particularly high for either group, but aggregated over the course of the school year, the additional time adds up considerably.