Annual Results 2020 Diversity & Exclusion: Sense of Belonging

This year for the first time, LSSSE introduced a set of questions focused on diversity and inclusion that supplement related questions from the primary survey. The Diversity and Inclusiveness Module examines environments, processes, and activities that reflect the engagement and validation of cultural diversity and promote greater understanding of societal differences. The 2020 LSSSE Annual Results Diversity & Exclusion report presents data about how diversity in law school can prepare students for the effective practice of law upon graduation. In this post, we explore how sense of belonging at law school varies among students from different backgrounds.

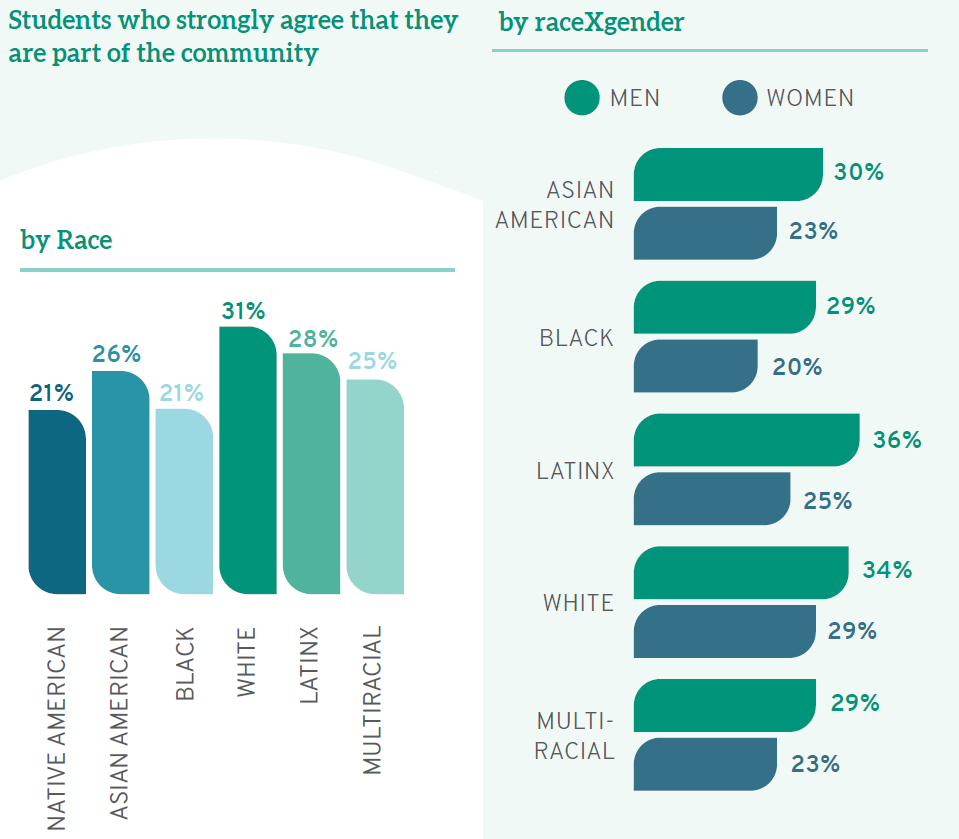

Scholarly research indicates that students who have a strong sense of belonging at their schools are more likely to succeed.1 Generally, belonging refers to feeling like part of the institutional community, fitting in, and being comfortable on campus.2 Using a number of separate indicators, LSSSE data on diversity and inclusiveness show that White students are more likely to have a strong sense of belonging than their classmates of color. For instance, when asked whether they feel they are "part of the community at this institution," a full 31% of White students strongly agree—though lower percentages of students of color do, including only 21% of Native American and Black students. Even more problematic when considering the importance of building an inclusive community: women of color are more likely than men from their same racial/ethnic backgrounds to feel that they are not part of the campus community—including a whopping 34% of Black women law students nationwide. First-gen students also deserve greater support, as only 23% "strongly agree" that they feel like part of the community at their law school, compared to 31% of students whose parents have at least a bachelor’s degree.

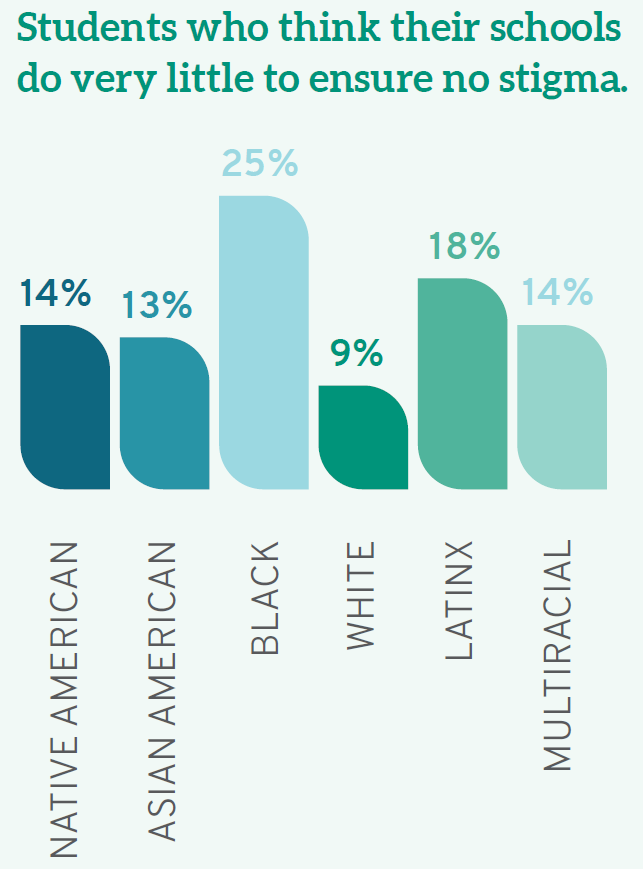

Students of color are also more likely than their White classmates to think their schools do "very little" to ensure students are not stigmatized based on various identity characteristics, including race/ethnicity, gender, religion, and sexual orientation. While only 9.3% of White students agree, 14% of Native Americans, 18% of Latinx students, and a full quarter (25%) of Black students believe their schools do "very little" to emphasize that students are not stigmatized based on identity. Similarly, 11% of heterosexual students think their schools do only "very little" to avoid identity-based stigma; conversely, 20% of gay students, 16% of lesbians, 15% of bisexual students, and 19% of those who identify as another sexual orientation see their schools as doing "very little" in this regard. Taken together, these findings suggest that those most likely to suffer stigma are also those most likely to think their schools do very little to protect them.

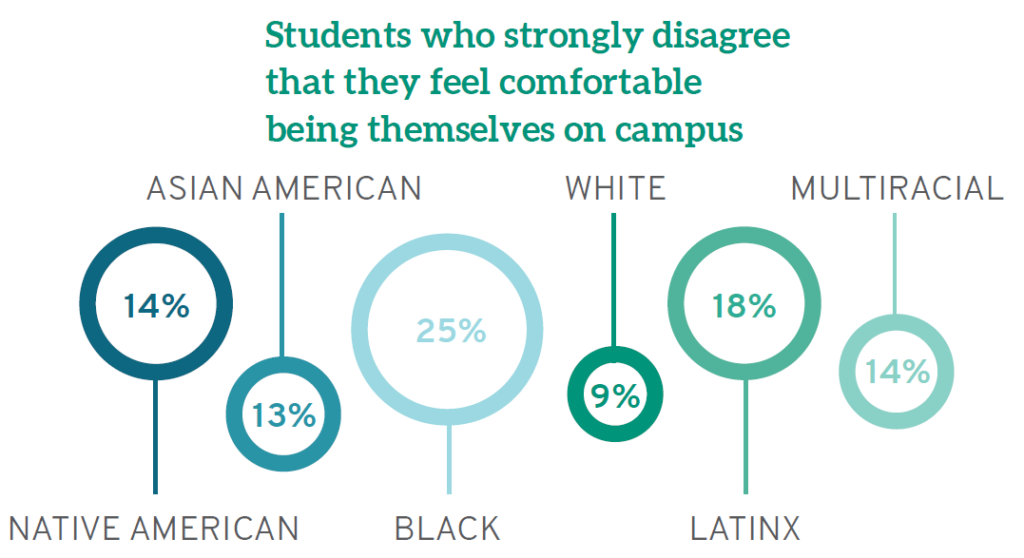

White students are also more likely than those from other backgrounds to be comfortable being themselves on campus, with only 12% noting they are not. Yet one out of every five (21%) law students who is Native American, Black, or Latinx notes that they do not "feel comfortable being myself at this institution."

There are also disturbing disparities when considering parental education—a strong proxy for family socioeconomic status. Being comfortable on campus increases almost in lockstep with increases in parental education; a full 32% of law students whose parents did not finish high school are uncomfortable being themselves on campus, compared to just 12% of those who have a parent with a doctoral or professional degree.

The overarching theme from this report is that those who are most affected by policies involving diversity—the very students who are underrepresented, marginalized, and non-traditional participants in legal education—are the least satisfied with diversity efforts on campuses nationwide. Nontraditional students remain marginalized on campus, left out of the community, devalued, and underappreciated. The solution is clear: institutions should place greater emphasis on valuing students from all backgrounds, creating an inclusive community, and integrating diversity into the curriculum. With that foundation, law schools can prepare students to interact in meaningful ways with diverse clientele, to first recognize and then resist instances of discrimination or harassment, and to meet the many challenges they will confront in their roles as lawyers and leaders.

1 Kuh, G. D., Kinzie, J., Buckley, J. A., Bridges, B. K., & Hayek, J. C. (2006). What matters to student success: A review of the literature (ASHE Higher Education Report). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

2 Strayhorn, T. L. (2018). College students’ sense of belonging: A key to educational success for all students. New York, NY: Routledge.

Annual Results 2020 Diversity & Exclusion: Institutional Support for Diversity

This year for the first time, LSSSE introduced a set of questions focused on diversity and inclusion that supplement related questions from the primary survey. The Diversity and Inclusiveness Module examines environments, processes, and activities that reflect the engagement and validation of cultural diversity and promote greater understanding of societal differences. The 2020 LSSSE Annual Results Diversity & Exclusion report presents data about how diversity in law school can prepare students for the effective practice of law upon graduation. In our next three posts, we will highlight key findings from the report and suggest some areas for improvement.

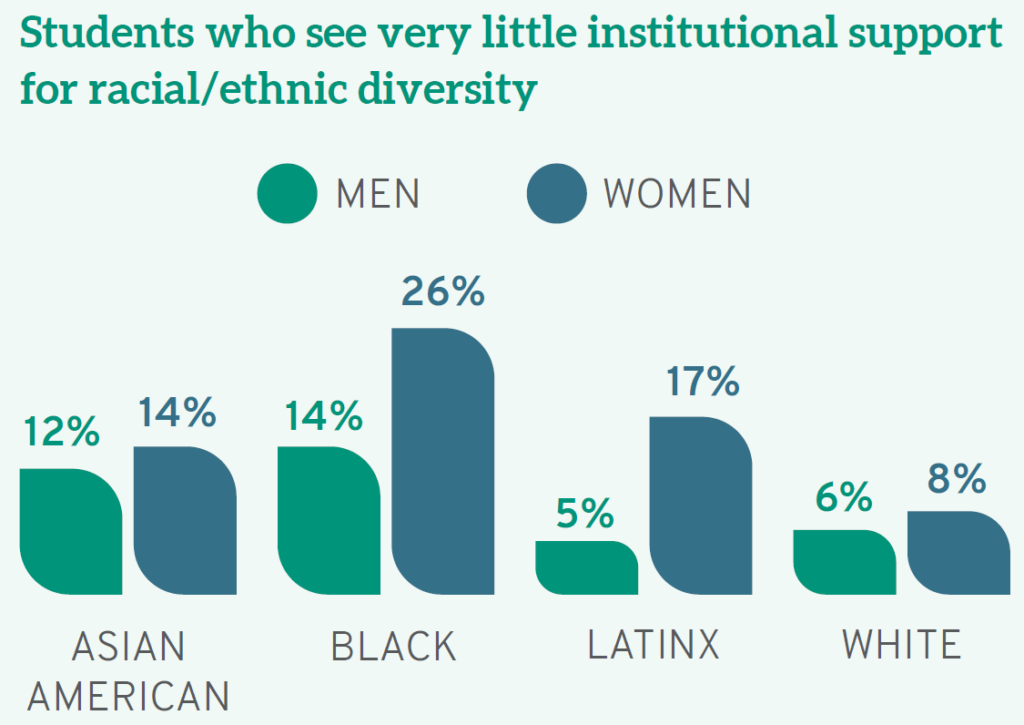

Support for diversity in law school must begin with the institution. Yet many students of color do not see their campus as supportive of racial/ethnic differences. Almost a quarter (23%) of Black law students nationwide say their schools do "very little" to create a supportive environment for race/ethnicity, compared to just 6.8% of White students. At the opposite end of the spectrum, 32% of White students believe their schools do "very much" to support racial/ethnic diversity, compared to only 18% of their Black classmates. Men (37%) are also more likely than women (26%) and those of another gender identity (7.5%) to believe their campus is very supportive of racial/ethnic diversity. Even more dramatic are intersectional identity findings, as a full 26% of Black women— more than any other raceXgender group—see their schools doing "very little" to create an environment that is supportive of different racial/ethnic identities, as compared to just 5.5% of White men (while 72% of White men believe their schools do "quite a bit" or "very much" in this arena).

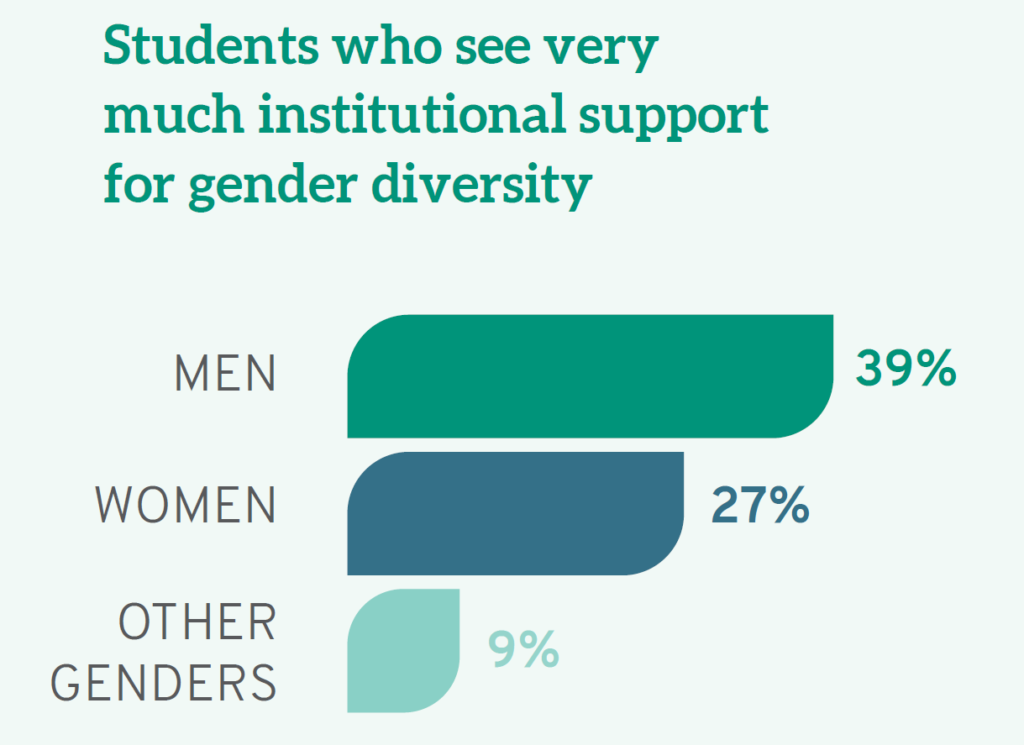

Men are also more likely to see their campus as a "supportive environment for gender diversity," with 39% believing this "very much" as opposed to 27% of women students, and only 9% of students who identify as another gender identity. Furthermore, White students as a whole (33%) see the campus as very supportive of people of different genders, compared to 21% of Native Americans and Black students. Again, the views of White male students differ significantly from most others with a full 40% seeing their campus as very supportive of gender difference. In short, women as well as others from less privileged groups do not see their schools as particularly supportive of gender inclusivity.

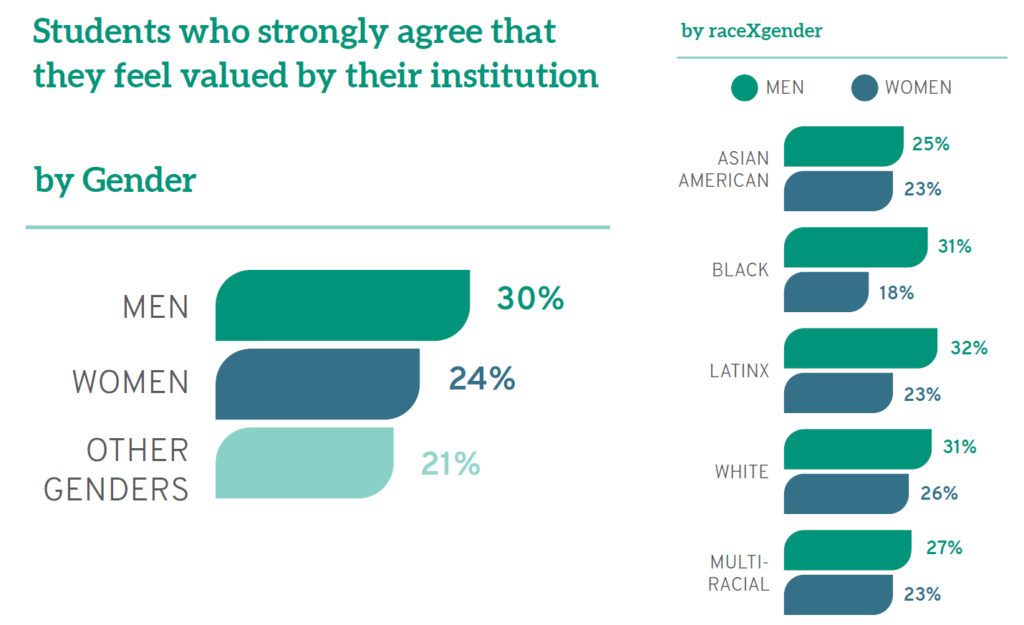

Not surprisingly, given the relative lack of support they see for racial/ethnic and gender diversity on campus, women and students of color also believe their schools are less invested in them as individuals. When asked whether they "feel valued" by their law school, a full 30% of men "strongly agree" compared to only 24% of women and 21% of those who identify as neither male or female. Similarly, the racial/ethnic group most likely to "strongly agree" is Whites (28%). In fact, while Latinos, White men, and Black men "strongly agree" that they are valued at roughly equal rates, men feeling more valued than women is consistent across every racial/ethnic group. Furthermore, students who are the first in their families to earn a college degree, often called "first-gen" students, feel less valued by their institution: a full third (33%) note they do not feel valued, compared to a quarter (25%) of others, which is also a significant proportion of law students overall.

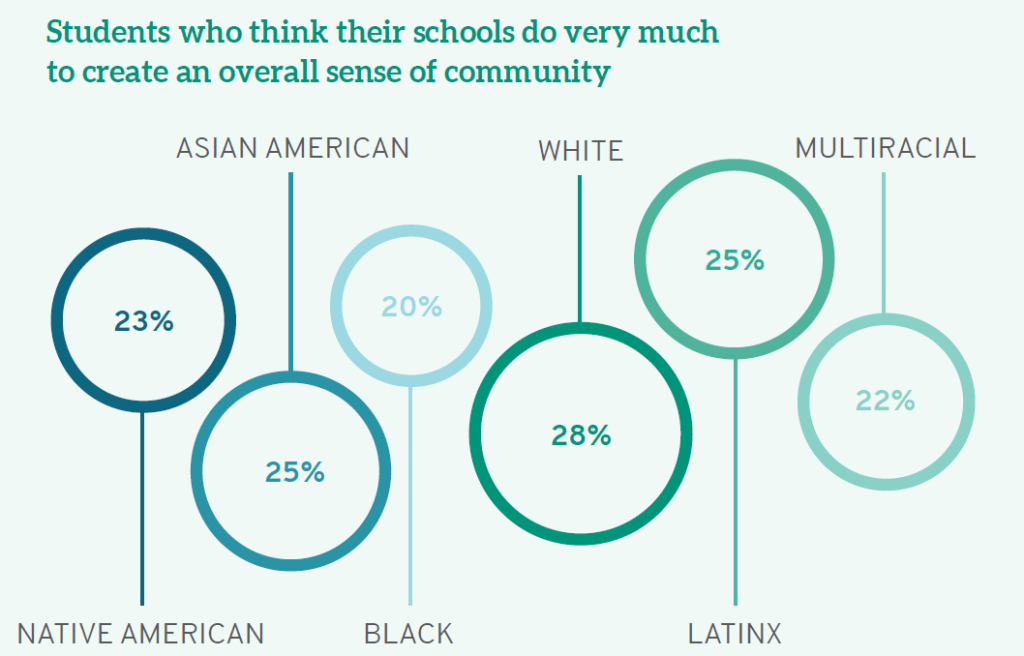

Institutions can put mechanisms in place to foster community among those on campus, regardless of their background or experiences. Finding this common ground helps all students understand that they belong and that others who may be different should be equally welcome. Again, White students are most likely to believe their institution emphasizes the importance of "creating an overall sense of community among students." While 28% of White students think their schools do this "very much," smaller percentages of students of color feel similarly. Even more disheartening, 18% of Black students and 14% of Latinx students think their schools do "very little" to foster community.

Many law schools have made concerted efforts to add student diversity to their campuses. But once students enroll, we owe it to them to provide a safe and welcoming environment, one where they feel valued, where they can be themselves, where they acquire the tools they need to succeed in the workplace, and where they can thrive. Admitting and even enrolling more students of color, first-gen students, students who identify as LGBTQ, and women is not enough unless that diversity is accompanied by inclusion. Law schools that want their students to succeed as future lawyers and leaders must commit to fostering a campus community where the most vulnerable and non-traditional are encouraged to reach their full potential, where faculty are expected to train students not only for the global marketplace but for the realities of American life, and where all students appreciate their own backgrounds, biases, and responsibilities to the profession.

Where do students get advice?

LSSSE’s optional Student Services module asks students about whether and how often they access academic and career services. Students draw from various sources to get advice about law school, legal education, and their future careers. Here, we look at the most commonly selected meaningful sources of advice for students and examine how patterns of advice-seeking change as students progress through law school.

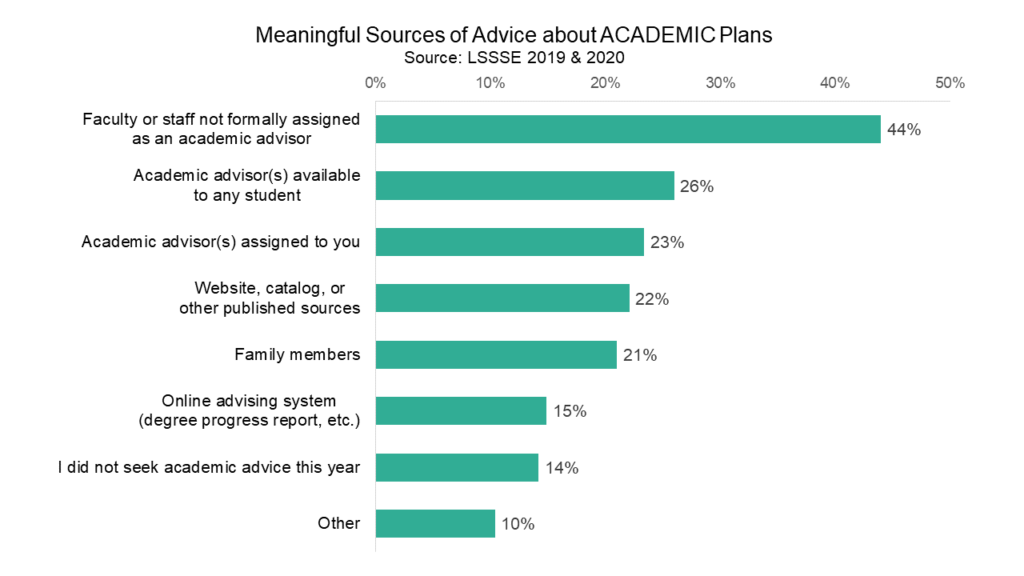

Advice about Academic Plans

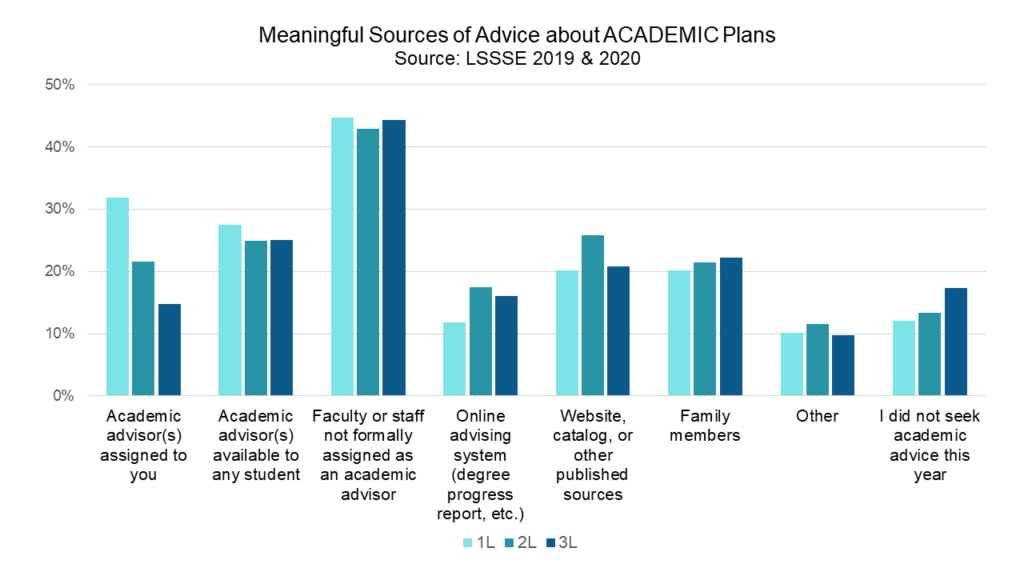

Faculty or staff not formally assigned as an academic advisor are the most common meaningful source of advice about academic planning. Over 40% of LSSSE respondents rely on these personal relationships that they develop with the law school professionals around them. Formal academic advisors –those assigned and those available to any students – are the second and third most commonly used sources of advice and were selected by 26% and 23% of students, respectively. About 22% of students consider websites, catalogs, or other published sources to be meaningful sources of advice about academic plans, and roughly one in five consulted family members. Only 14% of respondents did not seek academic advice from anyone during the current school year.

Students appear to rely less on assigned academic advisors as they progress through law school. Roughly one-third of 1L students say their assigned academic advisor was a meaningful source of advice, but only 15% of 3L students feel the same way. Perhaps unsurprisingly, 3L students were slightly less likely to seek academic advice than 1L and 2L students.

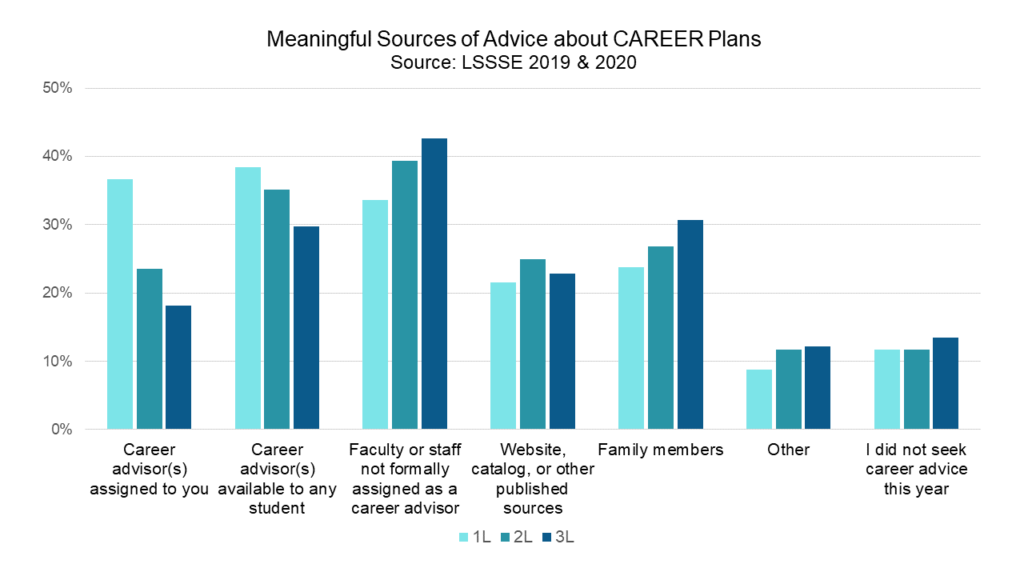

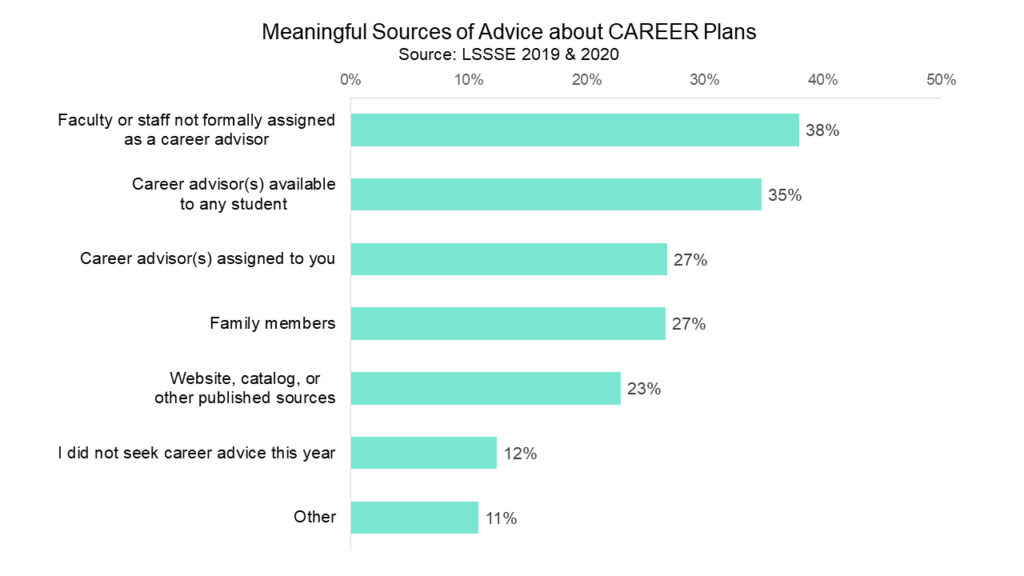

Advice about Career Plans

The ranking of meaningful sources of advice about career planning is remarkably similar to the ranking for advice about academic planning. Students highly value their relationships with law school faculty and staff when it comes to seeking career advice, ranking faculty or staff not formally assigned as a career advisor highest (38%), followed by career advisors available to any student (35%) and then assigned career advisors (27%). Interestingly, students were equally likely to select family members and assigned career advisors as meaningful sources of career advice. Twelve percent of respondents did not seek any career advice during the current school year.

Students rely less on assigned career advisors as they progress through law school, which is similar to the pattern we saw for academic advising. However, the gradual decrease in reliance on formal career advising is somewhat mirrored by a gradual increase in reliance on advice from faculty or staff not formally assigned as career advisors. It would appear that as students refine their interests and form relationships with particular faculty or staff members, they start to rely more on personal relationships for career advising and less on relationships facilitated by the structure of law school.