This year for the first time, LSSSE introduced a set of questions focused on diversity and inclusion that supplement related questions from the primary survey. The Diversity and Inclusiveness Module examines environments, processes, and activities that reflect the engagement and validation of cultural diversity and promote greater understanding of societal differences. The 2020 LSSSE Annual Results Diversity & Exclusion report presents data about how diversity in law school can prepare students for the effective practice of law upon graduation. In our next three posts, we will highlight key findings from the report and suggest some areas for improvement.

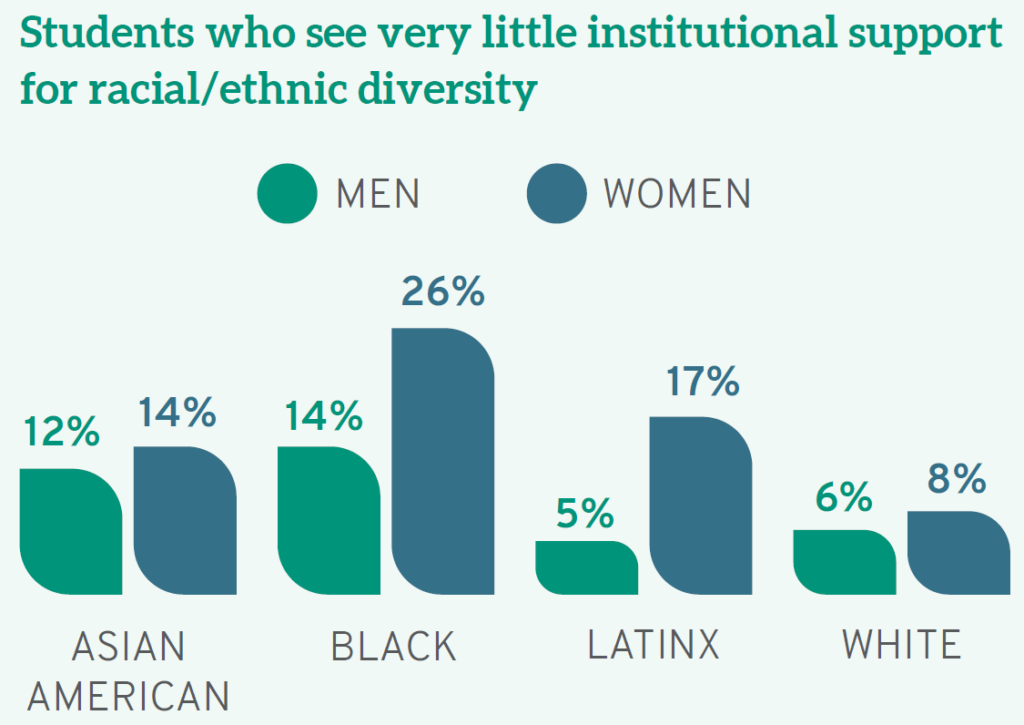

Support for diversity in law school must begin with the institution. Yet many students of color do not see their campus as supportive of racial/ethnic differences. Almost a quarter (23%) of Black law students nationwide say their schools do “very little” to create a supportive environment for race/ethnicity, compared to just 6.8% of White students. At the opposite end of the spectrum, 32% of White students believe their schools do “very much” to support racial/ethnic diversity, compared to only 18% of their Black classmates. Men (37%) are also more likely than women (26%) and those of another gender identity (7.5%) to believe their campus is very supportive of racial/ethnic diversity. Even more dramatic are intersectional identity findings, as a full 26% of Black women— more than any other raceXgender group—see their schools doing “very little” to create an environment that is supportive of different racial/ethnic identities, as compared to just 5.5% of White men (while 72% of White men believe their schools do “quite a bit” or “very much” in this arena).

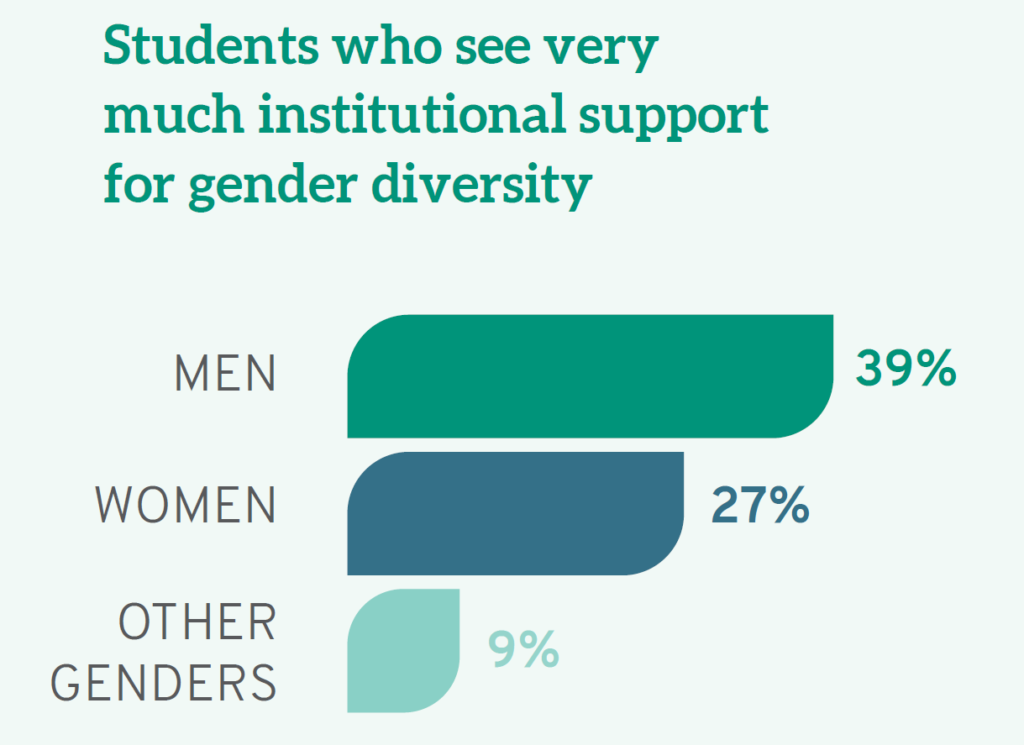

Men are also more likely to see their campus as a “supportive environment for gender diversity,” with 39% believing this “very much” as opposed to 27% of women students, and only 9% of students who identify as another gender identity. Furthermore, White students as a whole (33%) see the campus as very supportive of people of different genders, compared to 21% of Native Americans and Black students. Again, the views of White male students differ significantly from most others with a full 40% seeing their campus as very supportive of gender difference. In short, women as well as others from less privileged groups do not see their schools as particularly supportive of gender inclusivity.

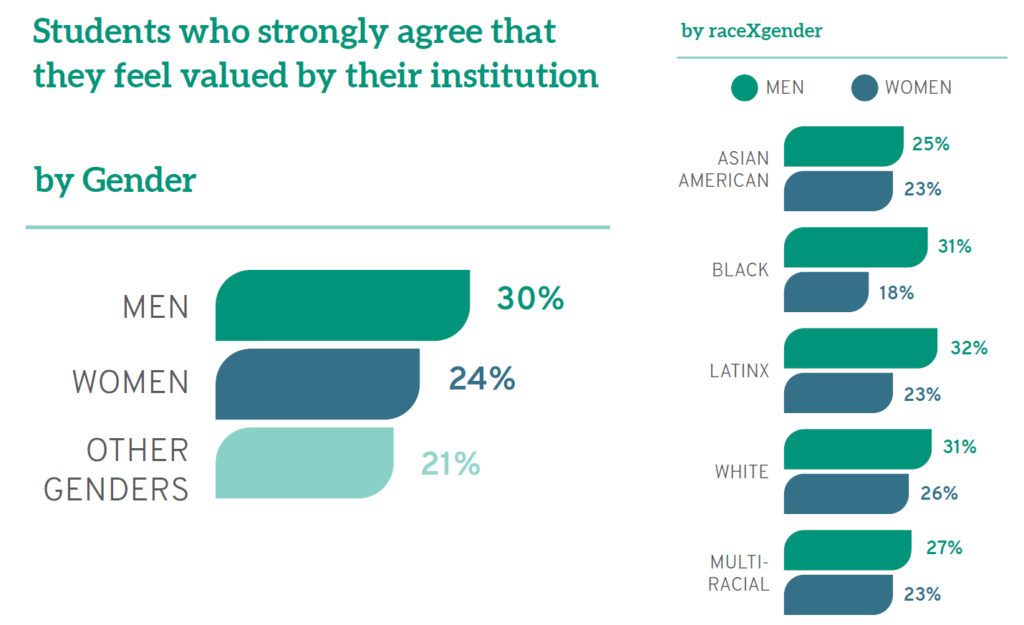

Not surprisingly, given the relative lack of support they see for racial/ethnic and gender diversity on campus, women and students of color also believe their schools are less invested in them as individuals. When asked whether they “feel valued” by their law school, a full 30% of men “strongly agree” compared to only 24% of women and 21% of those who identify as neither male or female. Similarly, the racial/ethnic group most likely to “strongly agree” is Whites (28%). In fact, while Latinos, White men, and Black men “strongly agree” that they are valued at roughly equal rates, men feeling more valued than women is consistent across every racial/ethnic group. Furthermore, students who are the first in their families to earn a college degree, often called “first-gen” students, feel less valued by their institution: a full third (33%) note they do not feel valued, compared to a quarter (25%) of others, which is also a significant proportion of law students overall.

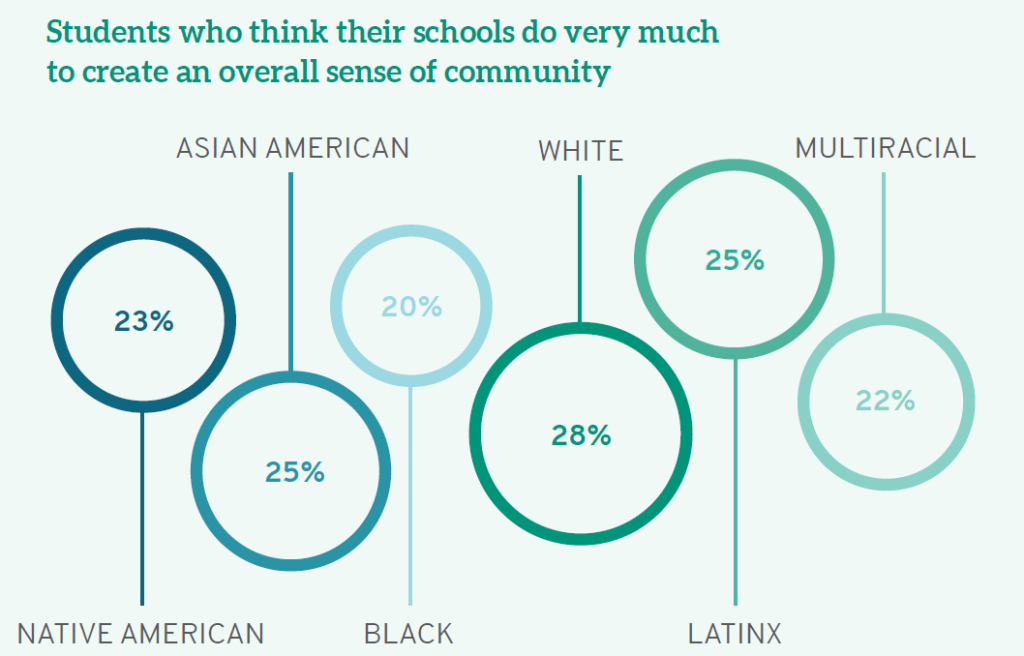

Institutions can put mechanisms in place to foster community among those on campus, regardless of their background or experiences. Finding this common ground helps all students understand that they belong and that others who may be different should be equally welcome. Again, White students are most likely to believe their institution emphasizes the importance of “creating an overall sense of community among students.” While 28% of White students think their schools do this “very much,” smaller percentages of students of color feel similarly. Even more disheartening, 18% of Black students and 14% of Latinx students think their schools do “very little” to foster community.

Many law schools have made concerted efforts to add student diversity to their campuses. But once students enroll, we owe it to them to provide a safe and welcoming environment, one where they feel valued, where they can be themselves, where they acquire the tools they need to succeed in the workplace, and where they can thrive. Admitting and even enrolling more students of color, first-gen students, students who identify as LGBTQ, and women is not enough unless that diversity is accompanied by inclusion. Law schools that want their students to succeed as future lawyers and leaders must commit to fostering a campus community where the most vulnerable and non-traditional are encouraged to reach their full potential, where faculty are expected to train students not only for the global marketplace but for the realities of American life, and where all students appreciate their own backgrounds, biases, and responsibilities to the profession.