Better than BIPOC

Meera E Deo, JD, PhD

Meera E Deo, JD, PhD

The Honorable Vaino Spencer Professor of Law, Southwestern Law School

Director, Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE)

We should be precise with our language, especially when talking about race. In “Better than BIPOC,” I argue that BIPOC is a flawed term for empirical scholars to use, one that prioritizes historical oppression over ongoing realities and relies on virtue signaling rather than working toward meaningful change. In my previous essay “Why BIPOC Fails,” I explain how BIPOC can be misleading, confusing, and contribute to the invisibility of the very groups that should be centered in particular contexts. Thus, without the deep investment of community engagement and review, new labels—like BIPOC—run the risk of causing more harm than good. Instead, we should continue to use the term “people of color” when referencing this group in comparison to whites, while “women of color” is useful when considering raceXgender intersectionality. Banding together for mutual support and action has been critical for people from marginalized identities as they have worked toward lasting social change. Additionally, it is often important to disaggregate data to report on individual groups that could otherwise get lost under these larger umbrella terms.

The experiences of various communities in law school help illustrate the point that academics, advocates, and allies should use be careful in their language usage—especially when dealing with data. Grouping populations together is often instructive. It can also be necessary to disaggregate the data to deal with separate communities individually. Law student debt and experiences with issues of diversity are particularly instructive in explaining both paths.

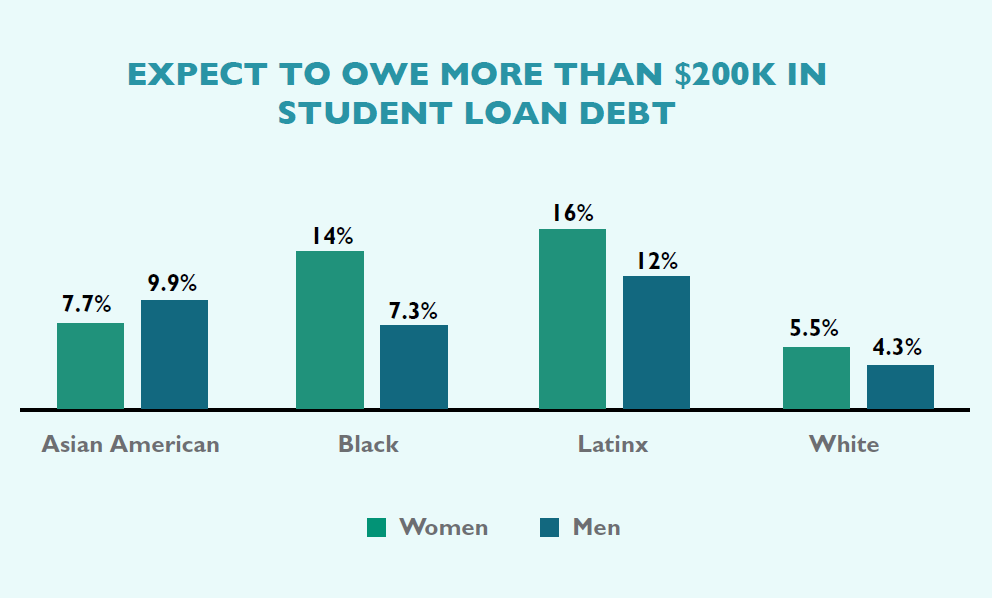

First, LSSSE data reveal that students of color carry more educational debt than white students. Here, it is appropriate and useful to group students of color together as a whole in comparing them with white students in terms of their overall debt loads. However, we can dig deeper to consider the intersectional experience of gender combined with race. If we ignore gender in this context, we run the risk of masking the distinct experiences of women of color compared with men of color as well as other groups. And there are differences. As I write in the article, “[H]igher percentages of Women of Color (23%) graduate with over $160,000 in law school debt, as compared with Men of Color (18%), white women (15%), and white men (12%).” While examining debt by raceXgender is thus more useful than considering race alone, being even more precise with the data and our language provides an opportunity to reveal more nuanced realities for communities within the women of color umbrella. As we share in our 2019 LSSSE Annual Report, The Cost of Women’s Success, the raceXgender groups most likely to carry the highest debt loads of over $200,000 are Latinas (16%) and Black women (14%), compared to lower percentages of Asian American women (7.7%), Black men (7.3%), Latino men (12%), and white men (4.3%). Thus, while it is correct to talk about the people of color and women of color carrying more debt than whites and those who are not women of color, it is more complete and sophisticated to explain how particular raceXgender groups—Black women and Latinas—have the highest debt loads of all. Precise racial language is instructive, particularly if we seek to craft solutions to ameliorate these challenges that are directly responsive to the needs of the populations affected.

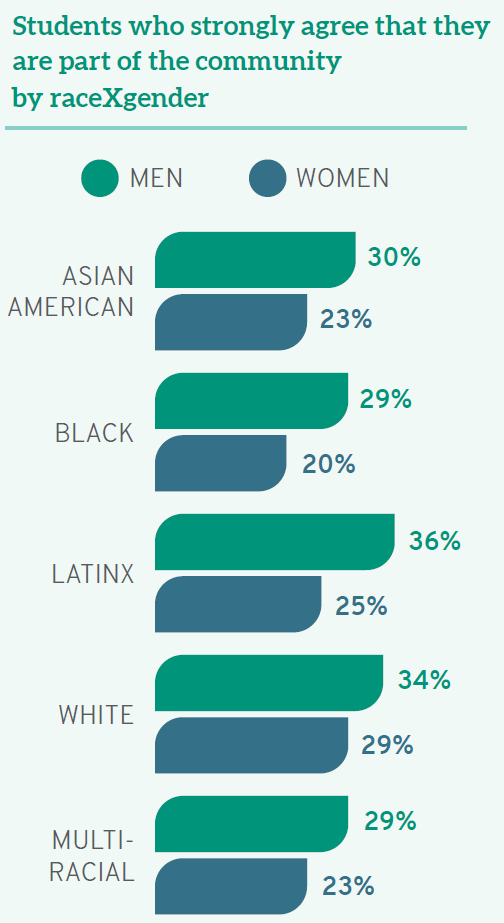

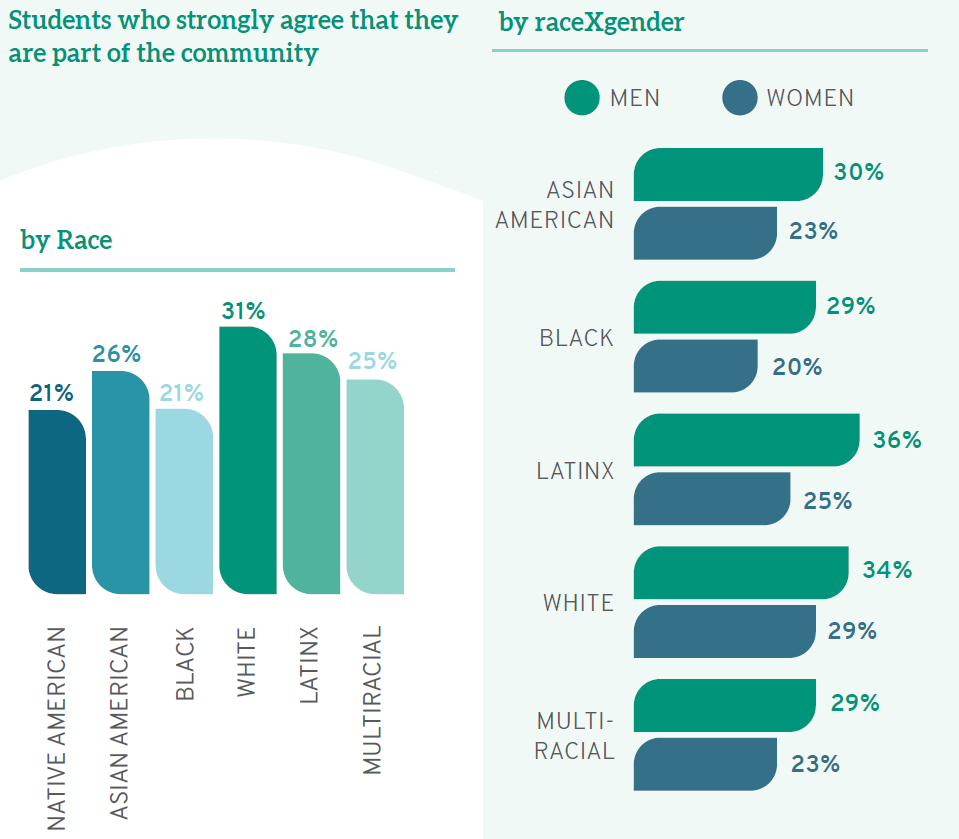

Student experiences with diversity provide another example of the benefits of careful language usage. Compared to their white peers, students of color have distinct opinions and experiences in law school when considering issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion. For example, although almost one-third (31%) of white law students “strongly agree” that they see themselves as part of the law school community, students of color are less likely to agree. As with debt levels, there are again additional distinctions based on raceXgender. In Better than BIPOC, I draw on data from the LSSSE 2020 Annual Report, Diversity & Exclusion, noting, “Fewer than one-quarter (23%) of women of color ‘strongly agree’ that they are part of the institutional community, compared to almost one-third (31%) of men of color.” Thus, distinctions based on race alone are not as precise as those disaggregating racial data by gender. In certain contexts, we also can—and should—go further still. By looking within the category of people of color, we can determine important differences between groups that administrators, faculty, and staff should consider in order to tailor solutions to the students who most need them. For instance, when we consider student belonging, “only 21% of Native American and Black law students see themselves as part of their law school community—compared to 31% of their white classmates, 25% of multiracial students, 26% of Asian Americans, and 28% of Latinx students.” Considering the student of color narrative as one group would tell an incomplete story as Black and Native law students are even more alienated nationally than even other students of color. Addressing their concerns will require us first to understand them, then to act.

Better than BIPOC also draws from the data behind my book project, Unequal Profession: Race and Gender in Legal Academia, to share examples from the law faculty context. I use findings on student evaluations and the challenges different populations face while navigating work/life balance to suggest when we should compare faculty of color as a whole to their white colleagues, when to disaggregate by race as well as gender to examine the experience of women of color faculty, and when to look more carefully within racial and gender-based categories to reveal important distinctions that could otherwise be hidden. Beyond the context of legal education, we can apply this thesis to frameworks as diverse as political engagement, workplace harassment, elementary school integration, diversity in corporate boards, and more. Different situations will naturally call for specific groups to be named and studied directly; that context, regardless of the terms currently en vogue, should drive the data used and arguments made in any endeavor. Working collectively serves a purpose, as does disaggregating the data. Through both efforts, we can understand the unique challenges facing different groups and work collectively to address them.

Annual Results 2020 Diversity & Exclusion: Sense of Belonging

This year for the first time, LSSSE introduced a set of questions focused on diversity and inclusion that supplement related questions from the primary survey. The Diversity and Inclusiveness Module examines environments, processes, and activities that reflect the engagement and validation of cultural diversity and promote greater understanding of societal differences. The 2020 LSSSE Annual Results Diversity & Exclusion report presents data about how diversity in law school can prepare students for the effective practice of law upon graduation. In this post, we explore how sense of belonging at law school varies among students from different backgrounds.

Scholarly research indicates that students who have a strong sense of belonging at their schools are more likely to succeed.1 Generally, belonging refers to feeling like part of the institutional community, fitting in, and being comfortable on campus.2 Using a number of separate indicators, LSSSE data on diversity and inclusiveness show that White students are more likely to have a strong sense of belonging than their classmates of color. For instance, when asked whether they feel they are "part of the community at this institution," a full 31% of White students strongly agree—though lower percentages of students of color do, including only 21% of Native American and Black students. Even more problematic when considering the importance of building an inclusive community: women of color are more likely than men from their same racial/ethnic backgrounds to feel that they are not part of the campus community—including a whopping 34% of Black women law students nationwide. First-gen students also deserve greater support, as only 23% "strongly agree" that they feel like part of the community at their law school, compared to 31% of students whose parents have at least a bachelor’s degree.

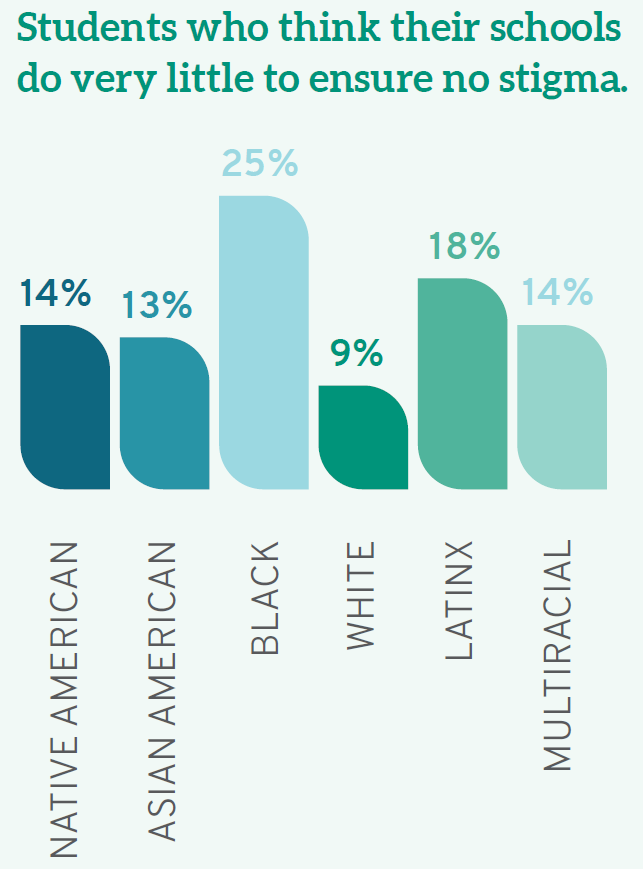

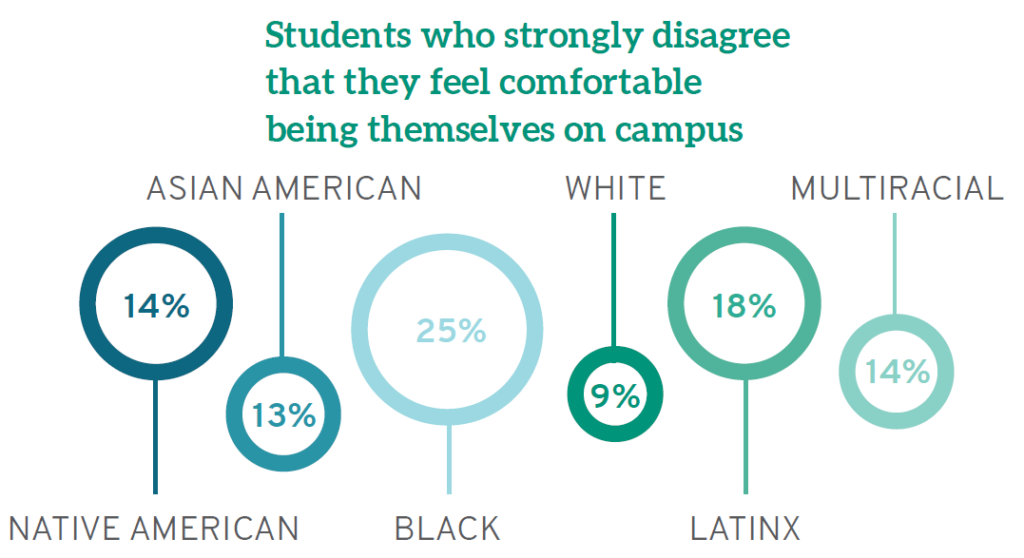

Students of color are also more likely than their White classmates to think their schools do "very little" to ensure students are not stigmatized based on various identity characteristics, including race/ethnicity, gender, religion, and sexual orientation. While only 9.3% of White students agree, 14% of Native Americans, 18% of Latinx students, and a full quarter (25%) of Black students believe their schools do "very little" to emphasize that students are not stigmatized based on identity. Similarly, 11% of heterosexual students think their schools do only "very little" to avoid identity-based stigma; conversely, 20% of gay students, 16% of lesbians, 15% of bisexual students, and 19% of those who identify as another sexual orientation see their schools as doing "very little" in this regard. Taken together, these findings suggest that those most likely to suffer stigma are also those most likely to think their schools do very little to protect them.

White students are also more likely than those from other backgrounds to be comfortable being themselves on campus, with only 12% noting they are not. Yet one out of every five (21%) law students who is Native American, Black, or Latinx notes that they do not "feel comfortable being myself at this institution."

There are also disturbing disparities when considering parental education—a strong proxy for family socioeconomic status. Being comfortable on campus increases almost in lockstep with increases in parental education; a full 32% of law students whose parents did not finish high school are uncomfortable being themselves on campus, compared to just 12% of those who have a parent with a doctoral or professional degree.

The overarching theme from this report is that those who are most affected by policies involving diversity—the very students who are underrepresented, marginalized, and non-traditional participants in legal education—are the least satisfied with diversity efforts on campuses nationwide. Nontraditional students remain marginalized on campus, left out of the community, devalued, and underappreciated. The solution is clear: institutions should place greater emphasis on valuing students from all backgrounds, creating an inclusive community, and integrating diversity into the curriculum. With that foundation, law schools can prepare students to interact in meaningful ways with diverse clientele, to first recognize and then resist instances of discrimination or harassment, and to meet the many challenges they will confront in their roles as lawyers and leaders.

1 Kuh, G. D., Kinzie, J., Buckley, J. A., Bridges, B. K., & Hayek, J. C. (2006). What matters to student success: A review of the literature (ASHE Higher Education Report). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

2 Strayhorn, T. L. (2018). College students’ sense of belonging: A key to educational success for all students. New York, NY: Routledge.

Guest Post: A LSSSE Collaboration on the Role of Belonging in Law School Experience and Performance

Guest Post By Victor D. Quintanilla, Professor at Indiana University Maurer School of Law, co-Director of the Center for Law, Society & Culture

This year is the 15th anniversary of the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE). In just a short decade and a half, LSSSE has collected over 350,000 law student responses from 200 law schools forming one of the largest datasets that captures law student voices and experiences in law school. My collaborators and I are grateful for the opportunity to share how we harnessed LSSSE’s remarkable dataset to illuminate student experiences with the aim of improving legal education.

This year is the 15th anniversary of the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE). In just a short decade and a half, LSSSE has collected over 350,000 law student responses from 200 law schools forming one of the largest datasets that captures law student voices and experiences in law school. My collaborators and I are grateful for the opportunity to share how we harnessed LSSSE’s remarkable dataset to illuminate student experiences with the aim of improving legal education.

For the past three years, I have been working with an interdisciplinary team of researchers across several institutions—including Indiana University Bloomington, the University of Southern California, the University of California at Los Angeles, Wake Forest University, and Stanford University—to examine the under-recognized role that psychological friction plays in law school engagement and performance.

Psychological friction can manifest in several ways, including feeling isolated, stereotyped, or feeling that one doesn’t belong (academically, culturally, or socially). These feelings of non-belonging shape the psychological experiences and achievement of students (e.g., Walton & Cohen, 2007; 2011). In 2018, in collaboration with LSSSE, we added validated survey items to a pilot LSSSE module to examine students' experiences of belonging, belonging uncertainty, and stereotype threat in law school. Indeed, this kind of collaboration is just one example of the many fruitful ways that researchers interested in studying legal education can work with LSSSE to conduct important empirical research on legal education.

The Role of Social Belonging in the Transition to Law School

All students face challenges in the transition to law school, from developing new friends, to learning the legal concepts and professional skills explored in first-year courses, to building relationships with professors. But law students from disadvantaged social backgrounds, including racial and ethnic minority students and first-generation college students, may wonder whether a "person like me" will be able to belong or succeed in law school and the profession. One consequence is that when disadvantaged law students encounter common difficulties in the critical first weeks and months of law school—such as critical feedback from professors using the Socratic method, difficulty reading cases and materials, difficulty with legal writing exercises, or an absence of feedback—these difficulties can be interpreted as evidence that they may not belong or can’t succeed. This negative inference can become self-fulfilling for all students—and especially for students from disadvantaged social backgrounds.

These worries about belonging and potential are endemic in legal education, occurring at all stages of students’ early legal careers—from the transition to law school, to mastering daunting course material, to the disciplined synthesizing of information required during bar exam preparation.

When students worry that they may not belong in law school, they are more likely to experience anxiety that can interfere with learning and are less likely to reach out to faculty, join study groups, seek out friends, or succeed in the law school environment over time. As such, feelings of belonging may be one important predictor of law school engagement and success.

By analogy, one study with a large group of undergraduate students found that pre-college worries about belonging in college (e.g., "Sometimes I worry that I will not belong in college.") predicted full-time college enrollment the next year, even controlling for high school GPA, SAT-score, fluid intelligence, gender, and other personality differences (Yeager et. al., 2016).

Where do these worries about belonging come from? The quality of students’ social relationships in school is an important predictor of students’ sense of belonging in school (Murphy & Zirkel, 2015; Walton & Cohen, 2007). The quality of students’ social relationships in school shapes students’ experiences and academic outcomes. Students who have strong, positive relationships with peers and professors are more satisfied with their educational experiences, more academically motivated, perform better in school, and are less likely to drop out (Wilcox & Fyvie-Gauld, 2005; Kuh & Hu, 2001).

LSSSE Data Reveals The Importance of Social Belonging in Law School

Our research team adapted validated survey items measuring social belonging and its potential antecedents for the 2018 administration of the LSSSE survey. In this pilot module, over 4,000 students rated their experiences of belonging and belonging uncertainty by responding to items such as, "I felt like I belonged in law school," and "While in law school, how often, if ever did you wonder: 'Maybe I don’t belong in law school?'"

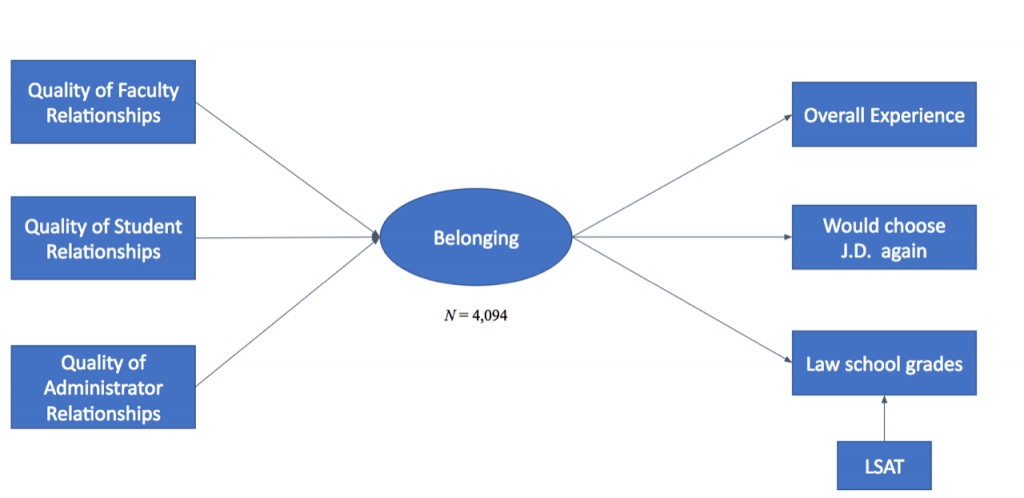

What did we find? First, we found that the quality of relationships with faculty, students, and administrators significantly predicted students’ feelings of belonging in law school. Thus, students’ relationships in law school predict their sense of belonging there.

Did law school belonging predict students’ performance? Yes. Indeed, a sense of belonging significantly predicted students’ overall experience in law school, whether they would choose to go to law school again, and their academic success (i.e., law school GPA) above and beyond traditional predictors such as LSAT scores and undergraduate GPA. Thus, law school belonging is a critical predictor of social and academic success among law students (Quintanilla, et. al, in prep).

Psychological Friction and WISE Interventions

While law schools seek to enhance and maintain student success, an almost-exclusive focus on cognitive predictors of success neglects other important social, contextual, and psychological factors—such as belonging in law school. Using LSSSE data, our research team found that students’ sense of belonging influences their law school satisfaction and grades, above and beyond the effects of LSAT score. We believe that law schools may be fertile grounds for social psychological interventions. "Wise interventions" focus on changing students’ construals of their environment (Walton & Wilson, 2018), and these may improve students’ sense of belonging and academic performance in law school—especially when coupled with changes in some of the structures and practices that dampen relationships and belonging in law school.

We look forward to continuing our collaboration with LSSSE and celebrate the continued growth of empirical legal education research that LSSSE affords. Congratulations to LSSSE on its 15-year anniversary!

*This research program and the design of related interventions are being conducted in collaboration with: Dr. Sam Erman (co-PI, University of Southern California), Dr. Mary C. Murphy (co-PI, IU Bloomington), Dr. Greg Walton (co-PI, Stanford University), Elizabeth Bodamer (IU Bloomington), Shannon Brady (Wake Forrest College), Evelyn Carter (UCLA BruinX), Trisha Dehrone (IU Bloomington), Dorainne Levy (IU Bloomington), Heidi Williams (IU Bloomington), and Nedim Yel (IU Bloomington), and supported by funding from the AccessLex Institute.