The Power of Critical Legal Research

The Power of Critical Legal Research

Priya Baskaran

American University Washington College of Law

Every year students ask me which classes are “the most important” to prepare them for successful and fulfilling legal careers. Should they focus on Bar classes or load up on Business Law for future corporate practice? Or should they opt for a seminar that will really engage their interest in human rights or environmental justice? Inevitably many students seek me out because as a professor at the top ranked clinical program at American University Washington College of Law, I actively engage in the practice of law. I also closely supervise and ultimately grade my clinic students on their own lawyering skills. The students who seek my advice do so because they are keen to acquire the skills and training to lawyer well. My response often surprises students: Take an advanced legal research class and focus on Critical Legal Research.

Legal research is too often conflated with navigating a commercial search database as quickly as possible. In reality, legal research is a complex, dynamic, and iterative process that requires a combination of critical thinking, analysis, strategy, and perseverance. Legal research is also a large part of the average attorney’s work life, particularly early career attorneys.[1] Finally, and most importantly in my mind, developing strong legal research foundations is essential to solving complex, real-world problems. This latter point is only increasing in relevance with the continued growth of generative AI.

Legal research provides students with a primer in intersecting legal regimes, showcasing how various subjects we teach in self-contained classes actually combine and impact the facts of any given case or circumstance.[2] Legal research then teaches students how to critically examine and sort these intersections into tiers of relevance for their various research questions and research tasks. Finally, legal research focuses on creating search plans and strategies. This includes understanding where they find this information – specialized secondary sources, primary authorities practice related resources, even specialized databases. Students also actively analyze and evaluate the results of their searches, making thoughtful and critical determinations when sorting and prioritizing information.[3]

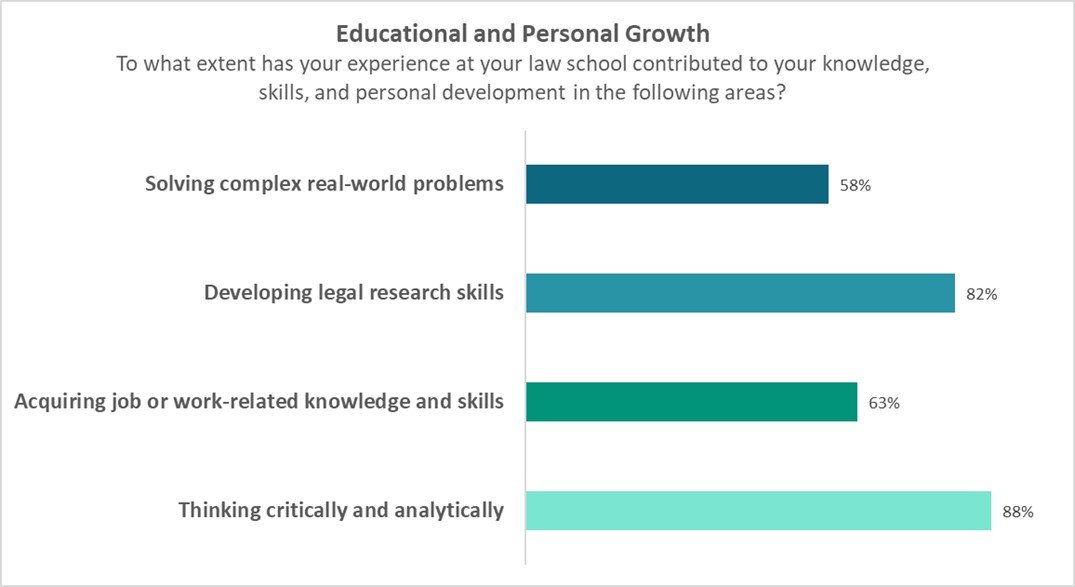

A properly taught legal research class excels in equipping students with the skills essential to good lawyering: 1) complex problem solving by researching messy or novel situations, 2) practical training in a core lawyering skill – legal research, 3) the ability to engage in active learning by directly researching, and 4) developing critical thinking and analysis skills. We see from LSSSE data that a majority of law students do learn these skills in law school.

*Students responding “quite a bit” or “very much”

In particular, a number of schools are increasingly using critical information literacy and Critical Legal Research to teach legal research. Critical legal information literacy is a pedagogy that challenges conceptions of legal research databases as neutral or comprehensive. Instead, critical information literacy teaches students that legal information is intentionally curated and categorized, often for commercial purposes.[4] This teaches students to be careful, thoughtful readers when their search results skew in favor of the status quo. Similarly, Critical Legal Research (CLR) builds on critical legal information literacy and incorporates critical legal theories and methodologies into the legal research process.[5] CLR challenges students to rethink their research questions, research strategies, and develop more expansive and thoughtful research plans in order to account for systemic bias. CLR underscores how the existing commercial search databases can entrench hegemonic interests, harming novel arguments that can advocate for more just outcomes.[6]

Take for example the case of a retail employee in June 2020. The employee works for a popular coffee chain that has been deemed “an essential business” during the COVID-19 epidemic. The employee routinely has to interface with customers who refuse to follow the safety protocols required by the county health department, including masking. Her manager requires employees still serve these customers despite the violation of the county health code and the CDC requirements. The employee finds her current work situation untenable for a number of reasons. First, she is deeply troubled by the request to break county law by violating the health department’s mandate. Second, she is concerned for her safety and the safety of her family (including an immunocompromised dependent). She feels like she has no choice but to quit her job but is worried about qualifying for unemployment insurance benefits.

We can immediately issue spot many complicated legal problems that will arise from this case. We can also identify the person being impacted by these “justice” issues – a worker facing both economic precarity and unsafe working conditions. Finally, we should be able to recognize that legal precedent will be exceedingly thin as June 2020 was still the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Building a case with little to no case law requires creative thinking and creative research strategies. What other sources may prove informative or be persuasive? Are there corollaries we can draw to other illnesses or other jurisdictions we should use to build our argument? Finally, we must identify and discuss that justice – when it goes against the dominant interests – requires creative and tireless advocacy on the part of the attorney.

Moreover, the continued growth of generative AI requires that we are even more thoughtful in training students.[7] A poorly trained student will use generative AI as a crutch, adding minimal to no value and simply regurgitating the algorithms findings. A well-trained researcher will identify the shortcomings of the AI tools, creating a comprehensive search plan and strategy that acknowledges and mitigates these flaws. For example, an AI tool may write a briefing memo summarizing the findings and state that the worker has little precedent and therefore a weak case. A well-trained researcher will be able to understand why this AI argument is insufficient for the client and for greater justice. The researcher may even be able to use this AI answer to play devil’s advocate, building a more creative response to counter the points generated by the status quo algorithm.

There is no shortage of conversation surrounding AI in law schools. In addition to discussing academic integrity and ethics, we must use this moment to explore critical pedagogies. How can we as professors help our students understand the blindspots of commercial AI? How can we train them to become better thinkers, lawyers, and advocates by exposing them to the limitations and injustice implications of both AI and traditional research? The answer may lie in leveraging critical legal information literacy and CLR in our own classes and pedagogies.

Although legal research is often limited to the first year curriculum, there are ample opportunities for instructors to engage with the topic in other courses. My forthcoming article, Searching for Justice: Incorporating Critical Legal Research in Clinic Seminar, includes a bibliography of scholarly work and pedagogical tools created by librarians and experts in the field. Professors can and should scaffold student learning by leveraging Critical Legal Research within their pedagogies, training more thoughtful and critical attorneys.

__

[1] Noting that new attorneys spend an average of one third of their time researching. Steven A. Lastres, Rebooting Legal Research in a Digital Age 3 (2013), https://www.lexis nexis.com/documents/pdf/20130806061418_large.pdf [https://perma.cc/SH5Q-Z2D3].

[2] THE BOULDER STATEMENTS ON LEGAL RESEARCH EDUCATION: THE INTERSECTION OF INTELLECTUAL AND PRACTICAL SKILLS (Susan Nevelow Mart ed., Heinemann, 2014). P. xii.

[3] Sarah Valentine, Legal Research as a Fundamental Skill: A Lifeboat for Students and Law Schools, 39 U. Balt. L. Rev. 173, 201 (2010).

[4] Yasmin Sokkar Harker, Legal Information for Social Justice: The New ACRL Framework and Critical Information Literacy, 2 Legal Info. Rev. 19,43 (2016-2017).

[5] .Nicholas F. Stump, Following New Lights: Critical Legal Research Strategies as a Spark for Law Reform in Appalachia, 23 Am. U. J. Gender Soc. Pol'y & L. 573, 603 (2015); Nicholas Mignanelli, Critical Legal Research: Who Needs It?, 112 LAW LIBR. J. 327 (2020).

[6] Nicholas F. Stump, COVID, Climate Change, and Transformative Social Justice: A Critical Legal Research Approach, 47 WM. & MARY ENVTL. L. & POL’Y REV. 147 (2022).

[7] For a fuller exploration of the intersection between generative and legal research, I recommend reading: Nicholas Mignanelli, Prophets for an Algorithmic Age, 101 B.U. Law Rev. 41, 44 (2021).

A CRT Assessment of Law Student Needs

Meera E Deo, JD, PhD

Meera E Deo, JD, PhD

The Honorable Vaino Spencer Professor of Law, Southwestern Law School

Director, Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE)

For over a century, American policy makers have recognized the need to provide personal support to students in primary and secondary school. Many states, including California, offer free or reduced lunch to students in need. Nurses and counselors are often available on campus to provide medical attention, academic guidance, and mental health support. Despite our clear understanding of the importance of these structures of support for children in the K-12 educational system, there are few mechanisms to support students in higher education. Yet many students in college, graduate school, and professional school also struggle to meet their basic needs.

In my new article, “A CRT Assessment of Law Student Needs,” and the accompanying Fact Sheet, I seek to convince policymakers that law students also need both administrative and legislative support to help them survive and thrive academically as well as professionally. LSSSE data show law students have been struggling to recover from the heightened challenges they endured during the early years of the pandemic. Struggles with food insecurity, financial anxiety, and emotional strain contribute to declining academic success, particularly for populations that were marginalized on law school campuses long before COVID. Legislative support is necessary to support students through this era so they can maximize their full potential.

Applying a CRT Framework

When we consider the CRT tenets of intersectionality and the compound effects resulting from those with devalued raceXgender characteristics specifically, it becomes evident that women of color law students are particularly at risk of falling behind or leaving law school altogether without greater support. The CRT concept of praxis further urges scholars to not only theorize about challenges and opportunities, but to put proposals into practice to achieve real change. Merging empirical methods with CRT, a new model of eCRT scholars “seek to rethink and change the premise of race scholarship in general by eschewing theoretical and methodological silos in pursuit of deepening our understanding of race and racism to advance racial justice.” Here, LSSSE data coupled with CRT theories are particularly instructive.

LSSSE Findings on Law Student Needs

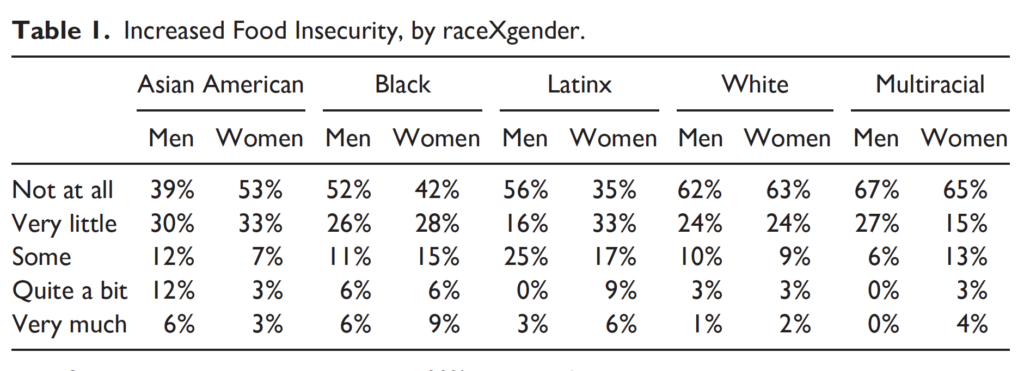

In 2021, LSSSE asked students about their experiences Coping with COVID. What they shared remains deeply disturbing, and even more so when we consider raceXgender effects. Women of color suffered with high levels of food insecurity—including 58% of Black women and 65% of Latinas who had increased concerns about whether they had enough food to eat.

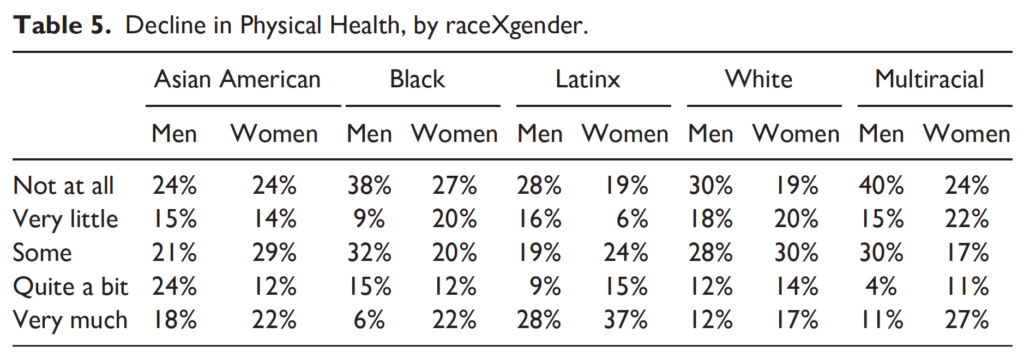

Students also reported declines in their physical health. For every racial group, higher percentages of women than men noted these declines—including 81% of Latinas (and 72% of Latino men).

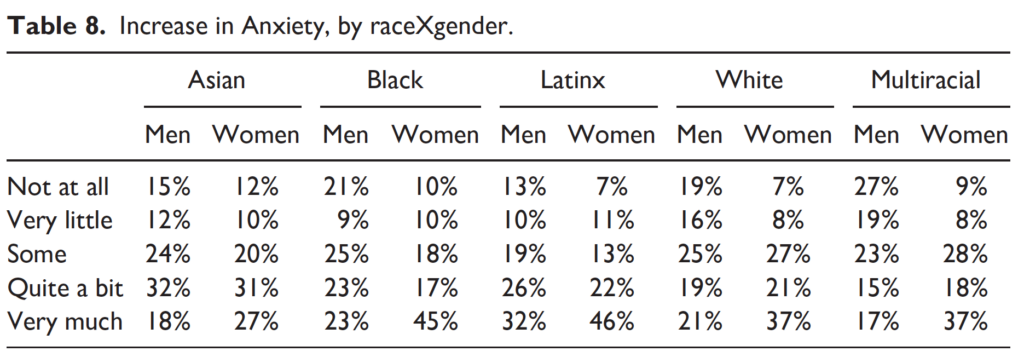

Most students also managed depression (85%) and anxiety (87%) that interfered with daily functioning—again, with marked raceXgender effects that bear out the CRT literature. For instance, while 73%–81% of white men, Black men, and multiracial men reported increased anxiety, a full 93% of white women, 90% of Black women, and 91% of multiracial women experienced the same.

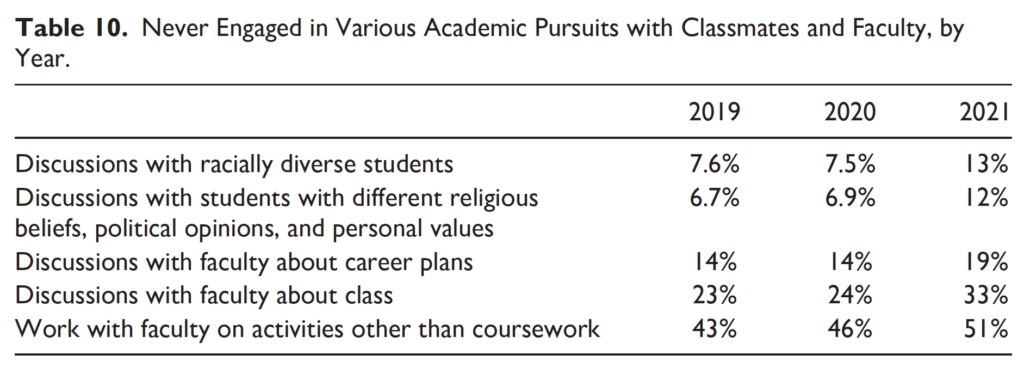

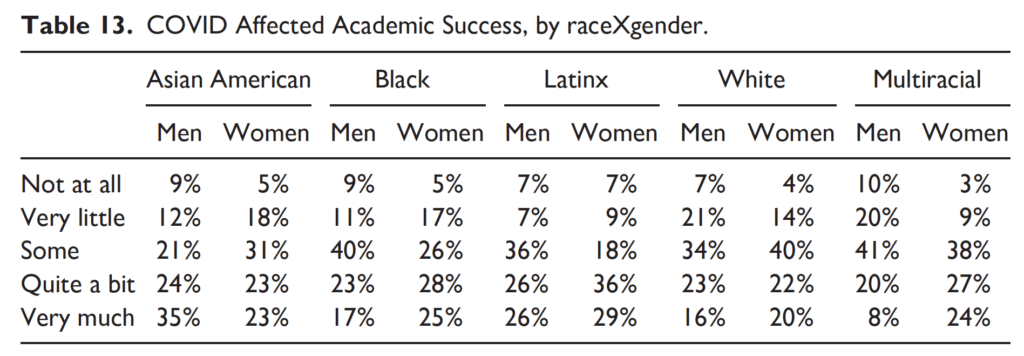

Struggles to meet their basic needs resulted in numerous missed opportunities for interaction with classmates and professors. One out of every five student respondents to the 2021 LSSSE survey (19%) never spoke with professors or other advisors about career plans or their job search. One third (33%) never discussed ideas from readings or classes with faculty members outside of class. There were also fewer opportunities for students to work with faculty on activities other than coursework (including committees, orientation, and student life activities); a full 51% of students never worked with faculty on these projects outside of class. Unsurprisingly, given all of these struggles, students also reported decreases in academic success, with women from most racial groups suffering more than men.

Institutional and Legislative Support

Most institutions already have a foundation to support students. But we can do better. In “A CRT Assessment of Law Student Needs,” I propose numerous options for administrators and policymakers to consider. For instance, while many campuses have food pantries to combat food insecurity, they should go beyond a locked room full of cans to prioritize accessibility by being open long hours or 24 hours, without an appointment or sign-in requirement, and on various parts of campus (not just one location that may be difficult for law students to access). Drawing from the CRT literature, food pantries should stock not only canned goods but also gift cards so students from varying backgrounds can purchase traditional or ethnic foods and fresh fruits and vegetables, and otherwise have agency over their food consumption.

Given increases in student anxiety and depression, law schools also should make mental health counseling available—with a focus on quality and accessibility for vulnerable populations. Counseling sessions should be free or low cost, with appointments scheduled via phone or through the click of a button, and meetings available both in person and online, as telehealth enables students of color—who rarely have on-site counseling available from professionals of their racial or cultural background—to connect online with counselors who work better for them.

Beyond institutional support, law students need legislative support. This is why the article includes an accompanying Fact Sheet—to make clear through brief bullet points and visualizations what the challenges are and how policymakers can help. Legislators could immediately reduce food insecurity by permanently expanding Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits to law students—without requiring them to work 20 hours per week or prove they care for dependents. Both the EATS Act and the Student Food Security Act provide pathways for SNAP expansion and extension; they are currently pending before Congress and should be strongly supported. California recently passed legislation expanding CalFresh (the state SNAP program) to those enrolled in institutions of higher education at least half-time. Other states should follow suit. Similarly, legislation should ensure mental health care is covered in standard insurance policies that tend to focus on physical health. Legislation could also offer financial assistance to institutions providing integrated mental health counseling for free or low-cost to law students. Additional legislative support could offer rental assistance, loan forgiveness, emergency funds, and other resources to law students in need.

Conclusion

Together, administrators and legislators can work to combat barriers facing law students that have intensified as a result of COVID. Once their basic needs are met, students can turn to maximizing their academic and professional success. Part of student success involves effectively and enthusiastically engaging in the intangibles of legal education, drawing from their own experiences and backgrounds to share and learn from classmates and faculty. When students are overcome by anxiety, depression, and loneliness, it is impossible to perform at their best.

Guest Post: Celebrating Asian-Americans: Reflections on Solidarity and Success in the Sunlight

Cyra Akila Choudhury

Professor of Law

FIU College of Law

Center for Law and Digital Technologies, Leiden University

Asian Americans have been in the news a great deal in the last several years. This year has been the year for Asians in the movies. Over the pandemic years, Asians and Asian Americans were in the news regularly for being victims of racial harassment and violence. That violence reached its extreme in the Atlanta massacre of six Korean American women working at a spa. The brief outpouring of support and solidarity after the shootings were welcome but not sustained. Within months, Asians went back to being a marginal minority group.

Even though we are the fastest growing minority, too often, we are only given attention in extraordinary moments: when we are the agents (Oscar winners, school shooters) or objects (victims of violence) of spectacular events. The most recent sustained attention given to Asian Americans has been in the context of the legal attacks on affirmative action.[1]

As Asians, we occupy the spotlight but not the sunlight, solidarity ebbs and flows, and our excellence is a double-edged sword. In this blog post, I reflect on the ways in which we have become agents for change in ways that overcome the binary glare of the spotlight or dark of its shadow. Asians have practiced and should continue to commit to radical solidarity both among ourselves and with other groups even as we unapologetically embrace our excellence. I offer these reflections as part of an ongoing conversation about what it means to be Asian American—an umbrella that includes a diverse group of people—in this moment.

- Seeking the sunlight not the spotlight

We are used to not being seen and not attracting attention to ourselves. Psychologist Jenny T. Wang writes in Permission to Come Home: Reclaiming Mental Health as Asian Americans,[2] that safety was one of the primary needs of her immigrant family. Safety meant following the plan of achieving stability and success without fuss. Often this means that we keep our heads down and get the job done, sacrificing what we truly love for the sake of duty. The light is shone on us by others when they perceive something worthy of notice.

In short, unless we are winning Oscars, running Google, or being massacred, people really don’t notice Asians. This is the spotlight effect. An external gaze that lights us up temporarily. As law students and lawyers, this might happen when we win an award or a big case. But what about when we’re not winning something? Asians deserve the sunlight and not the spotlight. That is to say, rather than being content with attention primarily when we achieve excellence, we deserve to be visible and present just as we are. Living in the sunlight also means being willing to be seen in our various workplaces and in society. Raising our hand in class, speaking in our own voice, running for public office, applying for promotion, and owning our histories and accomplishments.

- Practicing radical solidarity

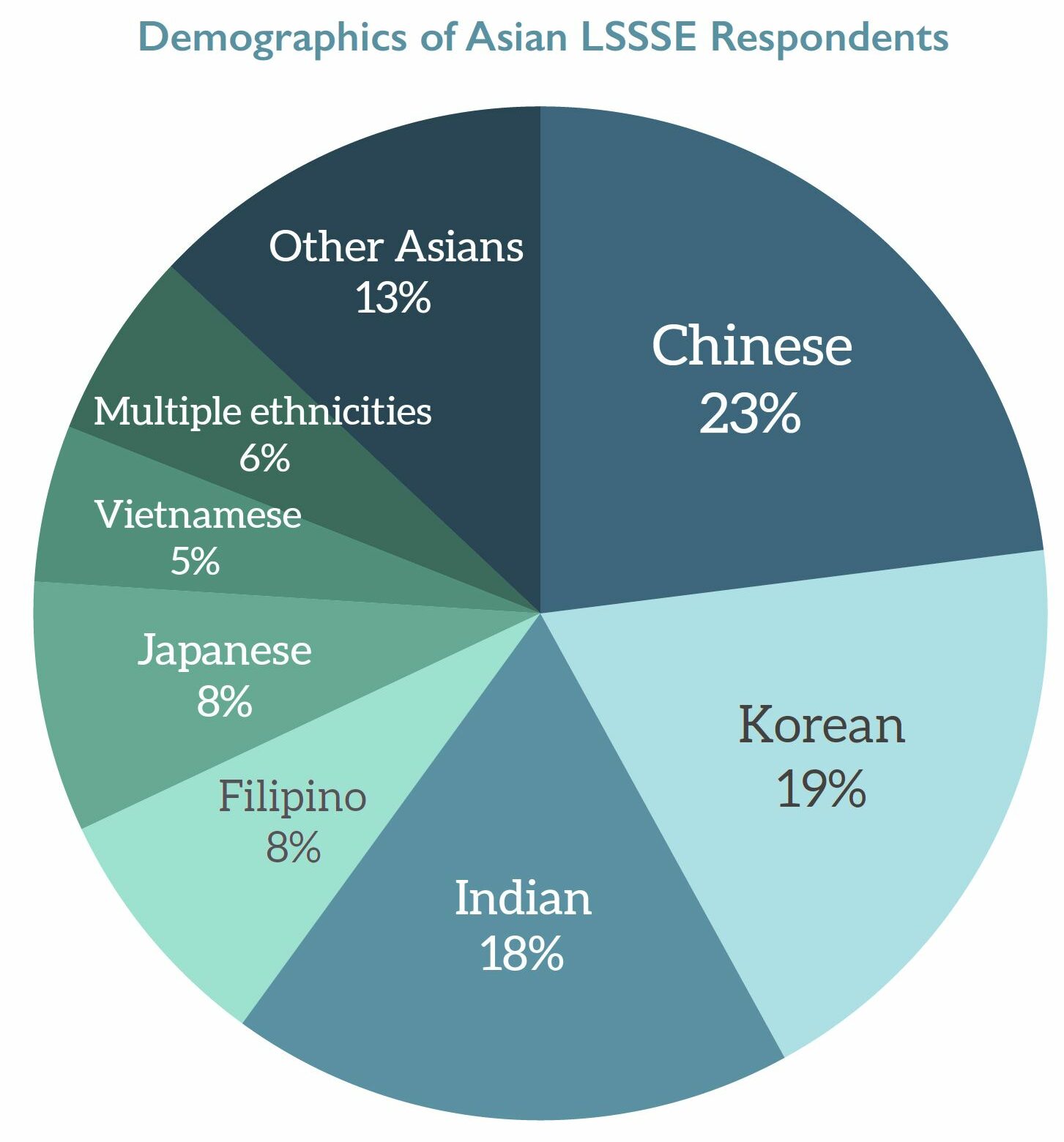

Asia is a vast geography with ancient civilizations. “Asian” is not a race, a cultural group, nor a linguistic group. Asian Americans hailing from different parts of Asia are a diverse group with many sub-diasporas. In legal education, for instance, Asian Americans include those with ancestors from China, Korea, India, the Philippines, Japan, and Vietnam. Increasingly, the shared experiences of these communities in the U.S. based on political marginalization, racism, immigration, and some cultural values have led to a growing sense of shared identity as well.

Yet, much more work needs to do be done to forge these nascent bonds. After the Atlanta massacre and the pandemic related violence against East Asian communities, there was a surge of broader recognition that Asian Americans were subjects of racism. This massacre was preceded by the massacre of six Sikhs in Wisconsin in 2012. This too was an Asian massacre and yet, we rarely connect the two as anti-Asian racism. Solidarity among Asians in an increasingly polarized political society has become very important if we want to shape and direct change.

Yet, much more work needs to do be done to forge these nascent bonds. After the Atlanta massacre and the pandemic related violence against East Asian communities, there was a surge of broader recognition that Asian Americans were subjects of racism. This massacre was preceded by the massacre of six Sikhs in Wisconsin in 2012. This too was an Asian massacre and yet, we rarely connect the two as anti-Asian racism. Solidarity among Asians in an increasingly polarized political society has become very important if we want to shape and direct change.

Asians have been partners in all of America’s struggles: the civil rights movement, labor rights, anti-war protests, and resistance to the War on Terror. We have demonstrated our solidarity with other groups, and we must do the same within our Asian communities as well. Radical solidarity, as I define it, means showing up for the struggle when called. When Black communities call for resistance, we show up. When Latinx communities ask for solidarity, we show up. Same for feminists and LGBTQ communities. We cannot succeed meaningfully in isolation. These struggles overlap within our communities. Moreover, radical solidarity is something we do without taking stock. I recall an acquaintance remarking in response to the Atlanta massacre, “I’d like to support Asians Americans, but they call the cops,” This is the opposite of radical solidarity. It is contingent solidarity and as we all know, fair-weather friends are of limited value. No single group has succeeded without radical solidarity from other groups. Without the civil rights movement, many of us would not even be Americans.

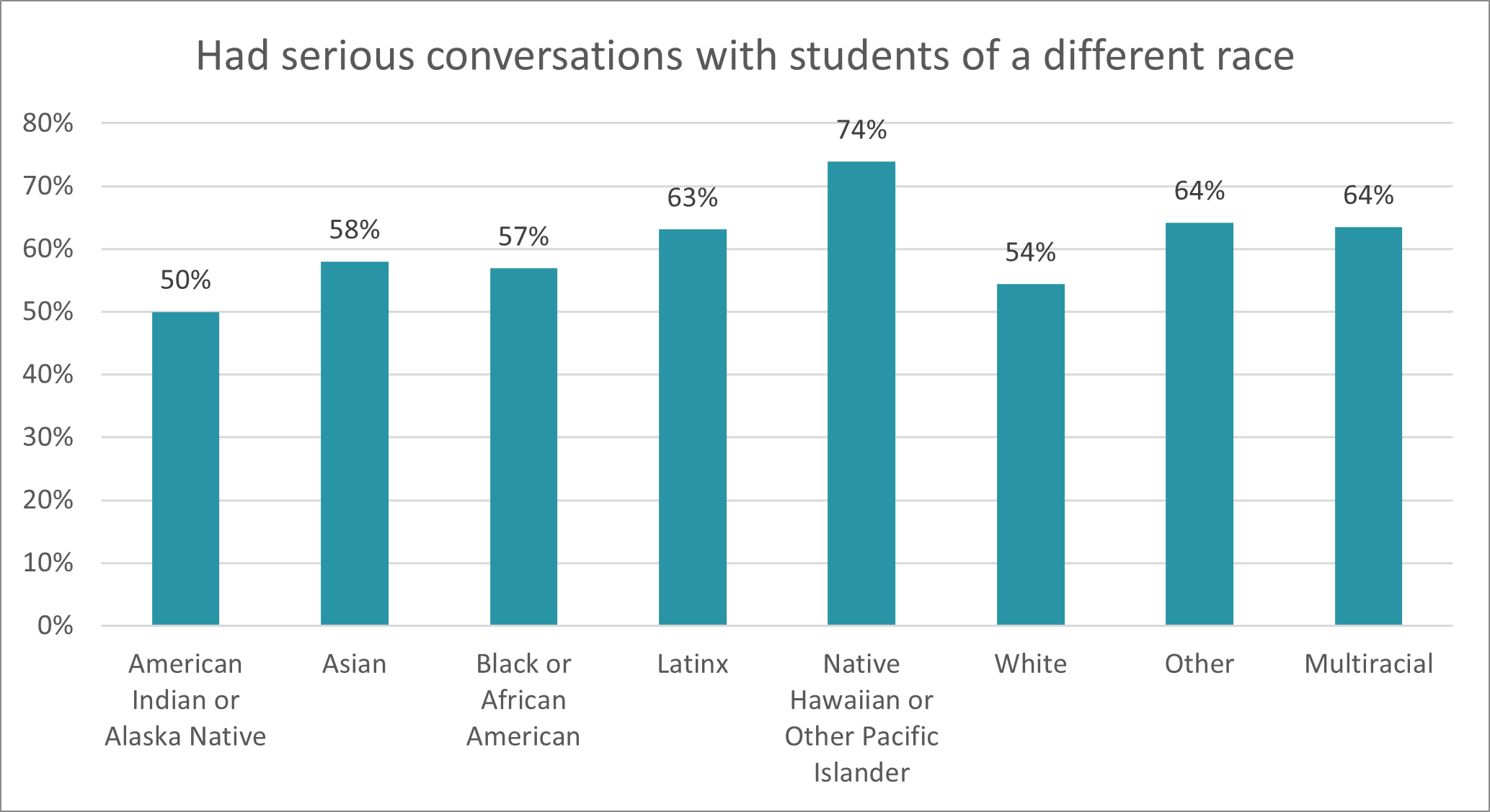

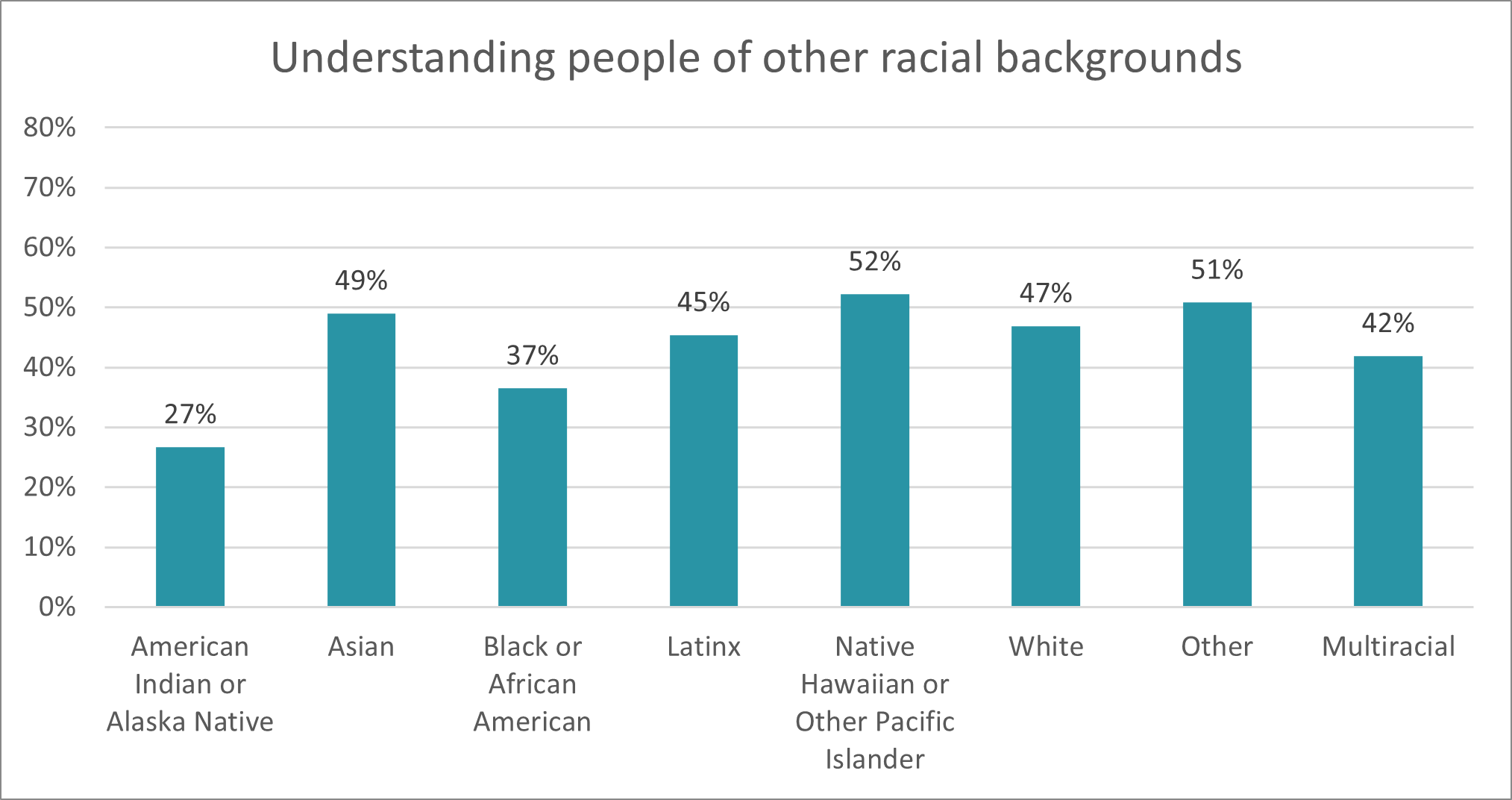

For law students, radical solidarity means working with other groups, showing up for their events, collaborating with others. LSSSE data make clear that law students excel at this already, both having serious conversations with students of a different race and working to understand students from different racial backgrounds.

For law professors, it means mentoring across various communities, perhaps reading across histories and cultures, and comparative research. For lawyers, it means building professional bridges and perhaps doing pro bono work for the communities that need it. Radical solidarity might require humility but not apology. I’m sure that there are many in our communities with very different ideas and politics but I speak here to the majority of us who believe in social equality.

- Embracing excellence and failure

Asians Americans are known as the “model minority.” It’s a pernicious myth about exceptionalism that is used to chastise other minority groups. In the last few years, weaponizing Asian excellence to harm other minority groups has been difficult for most Asians because we support affirmative action. How do we celebrate the very excellence that has been used to falsely exceptionalize us? Others have written extensively about the harms of this myth not only to others but to Asians themselves. Here I want to reflect on another consequence: a reluctance to embrace our successes and excellence as a community because it reinforces the myth.

The model minority myth has led to an ambivalence in celebrating our communities’ successes—an obstacle that few other groups have had to overcome. Achieving success because of hard work should be celebrated for itself while understanding that it says nothing about the value and success of any other group. Our radical solidarity with marginalized groups prevents us from claiming any exceptionalism for ourselves. And celebrating Asian Americans who succeed should not be mistaken for it. Nor should it be denigrated as mere borrowing, assimilationism, or white adjacency which is another kind of negative exceptionalism. Other groups’ similar successes are rarely spoken of in these denigrating ways.

So, celebrate the Indian kids who win spelling bees, the Chinese kid who wins the math competition while rejecting that Asians are somehow exceptional at spelling or math! Our stars are just that: stars. We have exceptional talents who deserve to be celebrated.

I want to end on a positive note on what is commonly thought to be a negative experience: failure. One stereotype about Asians is that, in our families and communities, failure is not an option. However, we should embrace failure as part of success rather than as a shameful shortcoming. As a law professor, I tell my students that they should learn from their failures, admit to them, overcome them, and move forward. Failures are inevitable and learning to cope with them without shame is important to the mental health of the community.[3] Asians fail as much as any other group and to deny this is to enforce an unacceptably high standard. To fully lay the model minority myth at rest, we must accept both our success and our failure. Asian belonging is not contingent on group accomplishment or excellence. We deserve the sunlight, to be visible, and fully accepted as Americans when we’re winning as well as when we’re not.

____

[1] Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard; Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina

[2] Jenny T. Wang, Ph.D., Permission to Come Home: Reclaiming Mental Health as Asian Americans (2023).

[3] See id.

Guest Post: Suits for Success

Colin Miller

Professor of Law

University of South Carolina School of Law

In 2018, I saw a tweet thread by attorney Alyssa Leader offering advice to law students on purchasing professional clothes on a budget. The thread was inspired by Leader’s memories of being a 1L and trying to swing a new wardrobe on student loans for job interviews. It led to me recalling my own time as a 1L, when all I had were ill-fitting Dockers and dress shirts, samples from my dad’s job as a Levi’s salesman. Knowing that many of my students faced similar issues, I researched whether any programs existed where job applicants could borrow professional clothes.

I came across the “tiebrary” program at the Paschalville Branch of the Free Library of Philadelphia. In a neighborhood with high rates of poverty, unemployment, and citizens returning from incarceration, the program allows patrons to check out professional clothes for job interviews. Further research revealed that this program was inspired by a similar one at the Queens Public Library, started when a library assistant gathered unused, clear VHS cases to display ties that patrons could check out. Articles on both of these programs sung their praises, with patrons crediting some of their success in the job market to their ability to dress for success.

Having fallen down the rabbit hole, I read studies suggesting that wearing professional clothes not only increases confidence and the chances of being hired, but also thinking and negotiating skills. Given how critical such skills are to success in summer jobs, I thought that a similar program for the students at our law school shouldn’t involve rentals; it should allow them to keep those clothes and wear them while they worked, not merely while they tried to be hired.

And thus, Suits for Success was born. First, we needed a space to house the program. Luckily, my Associate Dean counterpart, Susan Kuo, had started a free pantry for food insecure students. The space was big enough to house not only non-perishable food, but also a few clothing racks, allowing for one-stop shopping. After I took a trip to IKEA, we had all of the infrastructure we needed for the program.

Now, we simply needed to stock the space with suits, skirts, slacks, and other accessories for our clothing insecure students. Therefore, with assistance by my research assistant A.C. Parham, we conducted a month-long clothing drove where students could donate new and gently used professional clothes. We placed receptacles around the school where our students could drop off clothes that could help their classmates land the jobs of their dreams. Many of our students were thrilled at the opportunity to help their fellow students, building a sense of camaraderie around the law school.

But it went further than that. We promoted Suits for Success on social media, and it led to local lawyers seeing and understanding the need for the program. Soon, we started getting donations from members of the bar, who now better understood the financial issues facing our students and how they are orders of magnitude larger than the ones they faced when they were in school.

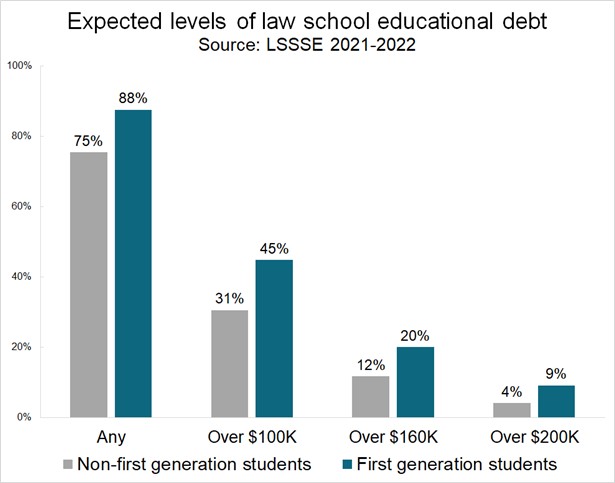

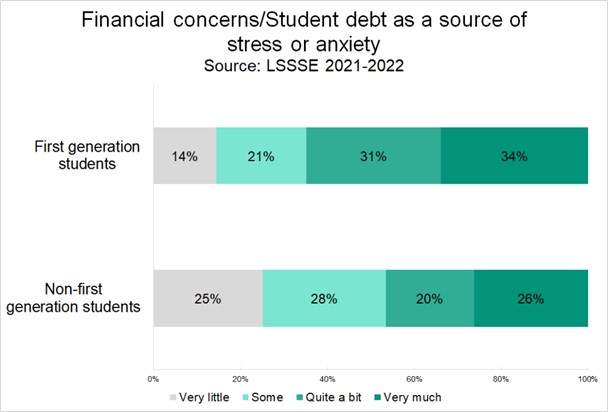

These are some of the same issues identified in the LSSSE data, concerns about making ends meet that disproportionately impact women and students of color. For instance, LSSSE data show that first-gen students (those who are the first in their families to attend college and therefore less likely to have professional clothes as hand-me-downs) also have the highest debt levels—leaving little extra money to spend on a new wardrobe. Financial concerns are also a huge source of stress for first-gen students, and many others. Being able to alleviate this in even a small way through Suits for Success is a simple way to support our students.

There are, of course, systemic issues that our food pantry and Suits for Success cannot and do not address. But we hope that these programs can at least make the difference at the margins and offer our students some security that they otherwise wouldn’t have.

Better than BIPOC

Meera E Deo, JD, PhD

Meera E Deo, JD, PhD

The Honorable Vaino Spencer Professor of Law, Southwestern Law School

Director, Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE)

We should be precise with our language, especially when talking about race. In “Better than BIPOC,” I argue that BIPOC is a flawed term for empirical scholars to use, one that prioritizes historical oppression over ongoing realities and relies on virtue signaling rather than working toward meaningful change. In my previous essay “Why BIPOC Fails,” I explain how BIPOC can be misleading, confusing, and contribute to the invisibility of the very groups that should be centered in particular contexts. Thus, without the deep investment of community engagement and review, new labels—like BIPOC—run the risk of causing more harm than good. Instead, we should continue to use the term “people of color” when referencing this group in comparison to whites, while “women of color” is useful when considering raceXgender intersectionality. Banding together for mutual support and action has been critical for people from marginalized identities as they have worked toward lasting social change. Additionally, it is often important to disaggregate data to report on individual groups that could otherwise get lost under these larger umbrella terms.

The experiences of various communities in law school help illustrate the point that academics, advocates, and allies should use be careful in their language usage—especially when dealing with data. Grouping populations together is often instructive. It can also be necessary to disaggregate the data to deal with separate communities individually. Law student debt and experiences with issues of diversity are particularly instructive in explaining both paths.

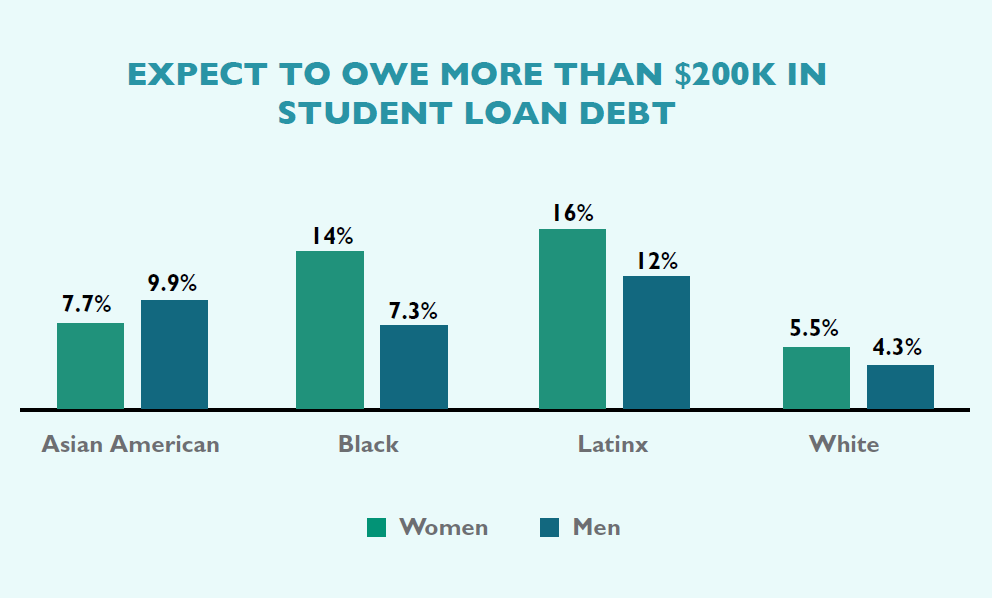

First, LSSSE data reveal that students of color carry more educational debt than white students. Here, it is appropriate and useful to group students of color together as a whole in comparing them with white students in terms of their overall debt loads. However, we can dig deeper to consider the intersectional experience of gender combined with race. If we ignore gender in this context, we run the risk of masking the distinct experiences of women of color compared with men of color as well as other groups. And there are differences. As I write in the article, “[H]igher percentages of Women of Color (23%) graduate with over $160,000 in law school debt, as compared with Men of Color (18%), white women (15%), and white men (12%).” While examining debt by raceXgender is thus more useful than considering race alone, being even more precise with the data and our language provides an opportunity to reveal more nuanced realities for communities within the women of color umbrella. As we share in our 2019 LSSSE Annual Report, The Cost of Women’s Success, the raceXgender groups most likely to carry the highest debt loads of over $200,000 are Latinas (16%) and Black women (14%), compared to lower percentages of Asian American women (7.7%), Black men (7.3%), Latino men (12%), and white men (4.3%). Thus, while it is correct to talk about the people of color and women of color carrying more debt than whites and those who are not women of color, it is more complete and sophisticated to explain how particular raceXgender groups—Black women and Latinas—have the highest debt loads of all. Precise racial language is instructive, particularly if we seek to craft solutions to ameliorate these challenges that are directly responsive to the needs of the populations affected.

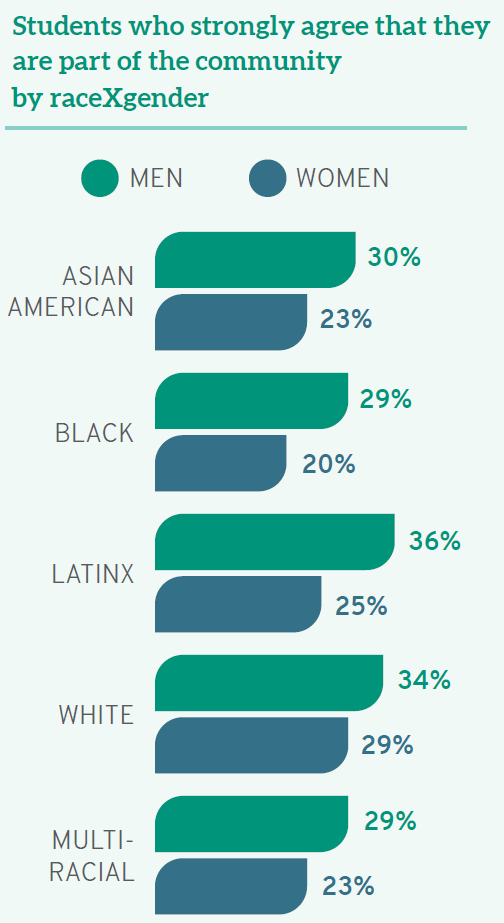

Student experiences with diversity provide another example of the benefits of careful language usage. Compared to their white peers, students of color have distinct opinions and experiences in law school when considering issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion. For example, although almost one-third (31%) of white law students “strongly agree” that they see themselves as part of the law school community, students of color are less likely to agree. As with debt levels, there are again additional distinctions based on raceXgender. In Better than BIPOC, I draw on data from the LSSSE 2020 Annual Report, Diversity & Exclusion, noting, “Fewer than one-quarter (23%) of women of color ‘strongly agree’ that they are part of the institutional community, compared to almost one-third (31%) of men of color.” Thus, distinctions based on race alone are not as precise as those disaggregating racial data by gender. In certain contexts, we also can—and should—go further still. By looking within the category of people of color, we can determine important differences between groups that administrators, faculty, and staff should consider in order to tailor solutions to the students who most need them. For instance, when we consider student belonging, “only 21% of Native American and Black law students see themselves as part of their law school community—compared to 31% of their white classmates, 25% of multiracial students, 26% of Asian Americans, and 28% of Latinx students.” Considering the student of color narrative as one group would tell an incomplete story as Black and Native law students are even more alienated nationally than even other students of color. Addressing their concerns will require us first to understand them, then to act.

Better than BIPOC also draws from the data behind my book project, Unequal Profession: Race and Gender in Legal Academia, to share examples from the law faculty context. I use findings on student evaluations and the challenges different populations face while navigating work/life balance to suggest when we should compare faculty of color as a whole to their white colleagues, when to disaggregate by race as well as gender to examine the experience of women of color faculty, and when to look more carefully within racial and gender-based categories to reveal important distinctions that could otherwise be hidden. Beyond the context of legal education, we can apply this thesis to frameworks as diverse as political engagement, workplace harassment, elementary school integration, diversity in corporate boards, and more. Different situations will naturally call for specific groups to be named and studied directly; that context, regardless of the terms currently en vogue, should drive the data used and arguments made in any endeavor. Working collectively serves a purpose, as does disaggregating the data. Through both efforts, we can understand the unique challenges facing different groups and work collectively to address them.