Preferences & Expectations for Employment After Law School by Race and Ethnicity

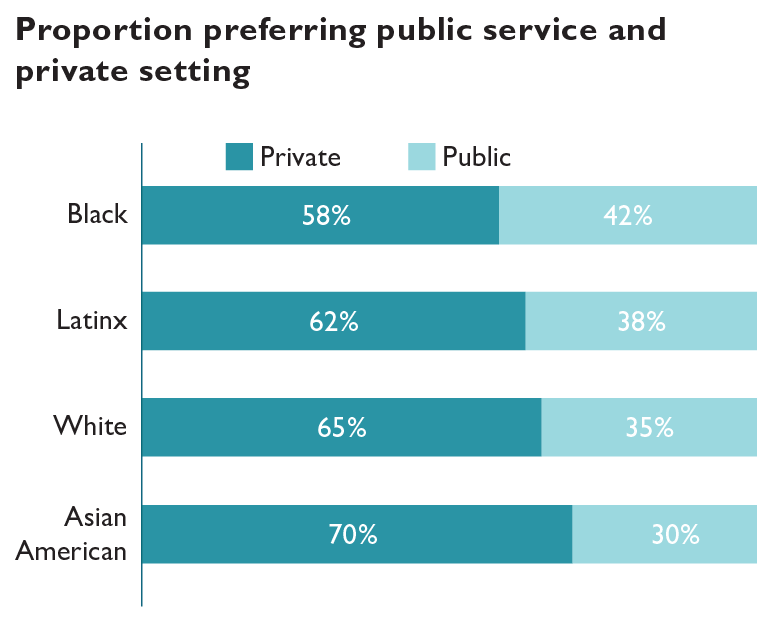

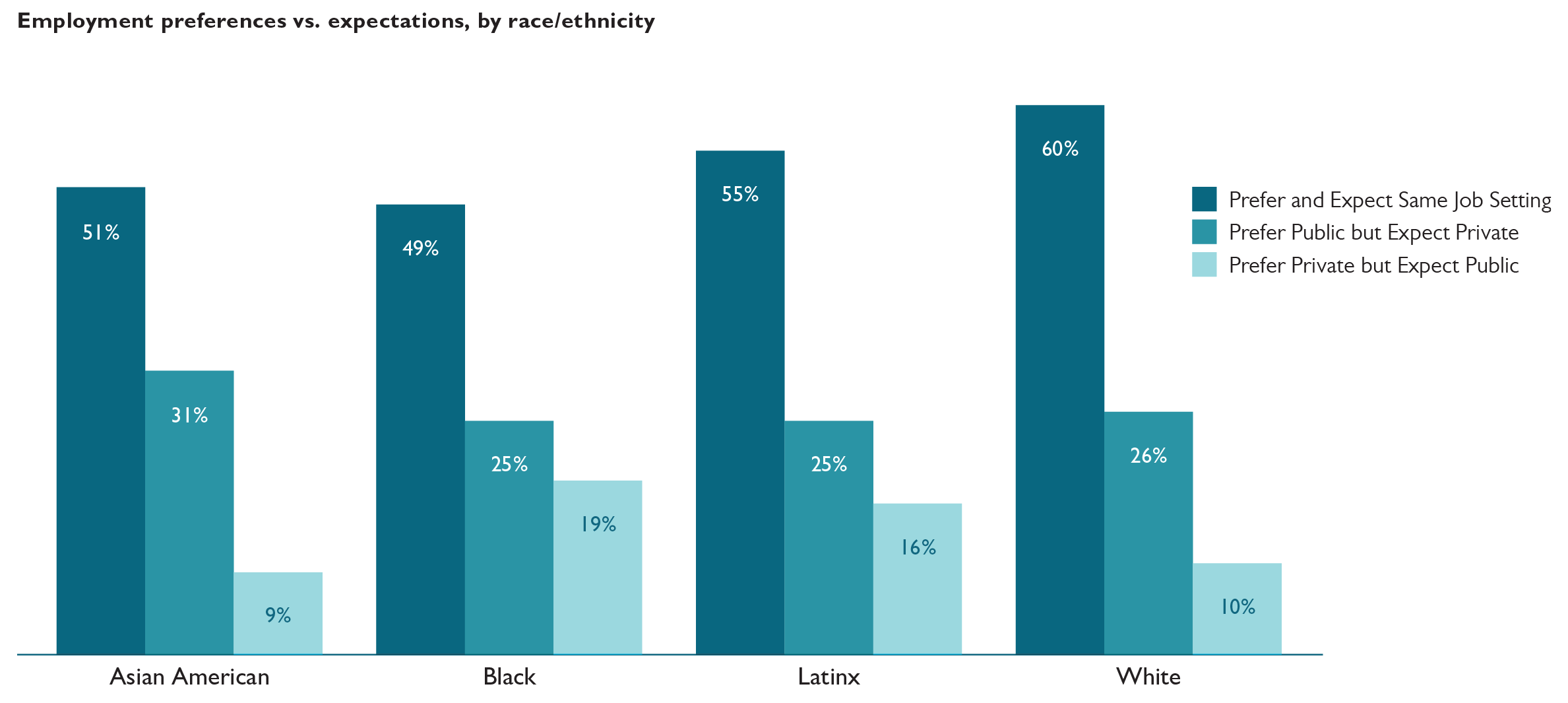

The newly released LSSSE 2017 Annual Results explore the relationship between students’ preferred and expected work settings post-graduation. Our most recent post in this series shared some general observations about the matches (and mismatches) between preferred and expected settings. In this post, we will share some insights into how these preferences and expectations are related to race and ethnicity.

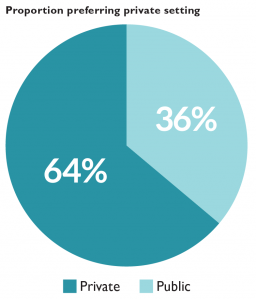

Overall, 64% of respondents prefer to work in the private sector. Almost 70% of Asian American respondents state a preference for working in a private setting, the largest proportion among the four racial and ethnic groups analyzed. Black respondents are most likely to prefer public service settings.

Black respondents are least likely to prefer and expect to work in the same individual setting, with less than half doing so, whereas White respondents (at 60%) are most likely. The proportion of respondents expecting to work in private settings increases among Asian American and White respondents, when compared to their preferences. Seventy-three percent of Asian American respondents expect to work in private settings, compared to 70% preferring to do so. Among White respondents, the proportion who expect to work in private settings is 68% compared to the 65% who prefer it. These two sets of proportions remain largely the same among Black and Latinx respondents.

Almost one-third of Asian American respondents who prefer public service settings expect to work in private settings, the highest proportion among all the racial and ethnic groups. Black respondents are most likely to prefer private settings but expect to work in public service.

Trends in Preferences & Expectations for Employment After Law School

The newly released LSSSE 2017 Annual Results explore the relationship between students’ preferred and expected work settings post-graduation. In a series of related blog posts, we will share tidbits of information about where law students hope to work, where they expect to work, and how these preferences and expectations vary by race and gender. In our final post, we will look at patterns in students’ preferred and expected work settings relative to their projected levels of student loan debt.

LSSSE asks respondents to identify the setting in which they would most prefer to work after graduation and the setting in which they most expect to work. Preferences can be seen as representing a respondent’s ideal outcome; expectations can be seen as representing perceptions of a realistic outcome. For both questions, respondents are asked to choose between sixteen answer options.

For purposes of much of the analyses in this report, the answer options were divided into two broad groups:

Public Service Settings

- Academic

- Government agency

- Judicial clerkship

- Legislative office

- Military

- Prosecutor’s office

- Public defender’s office

- Public interest group

Private Settings

- Accounting firm

- Business and industry

- Nonlegal organization

- Private firm – small (fewer than 10 attorneys)

- Private firm – medium (10-50 attorneys)

- Private firm – large (more than 50 attorneys)

- Solo practice

The “Other” response was removed from our analysis. The primary factor underlying the assignment of an answer option to one of the two groupings was whether a person working in that setting would likely qualify for Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF), which typically requires one to be employed in the government or non-profit sector. There is naturally some imprecision in the assignments.

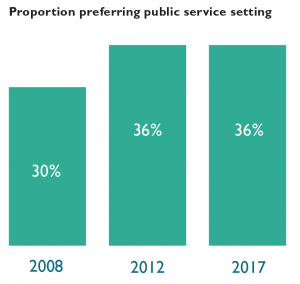

Sixty-four percent of respondents indicate a preference for working in one of the private settings, with the remaining 36% preferring public service. This proportion is unchanged from five survey administrations ago (2012) and higher than the 30% public service proportion ten administrations ago (2008).

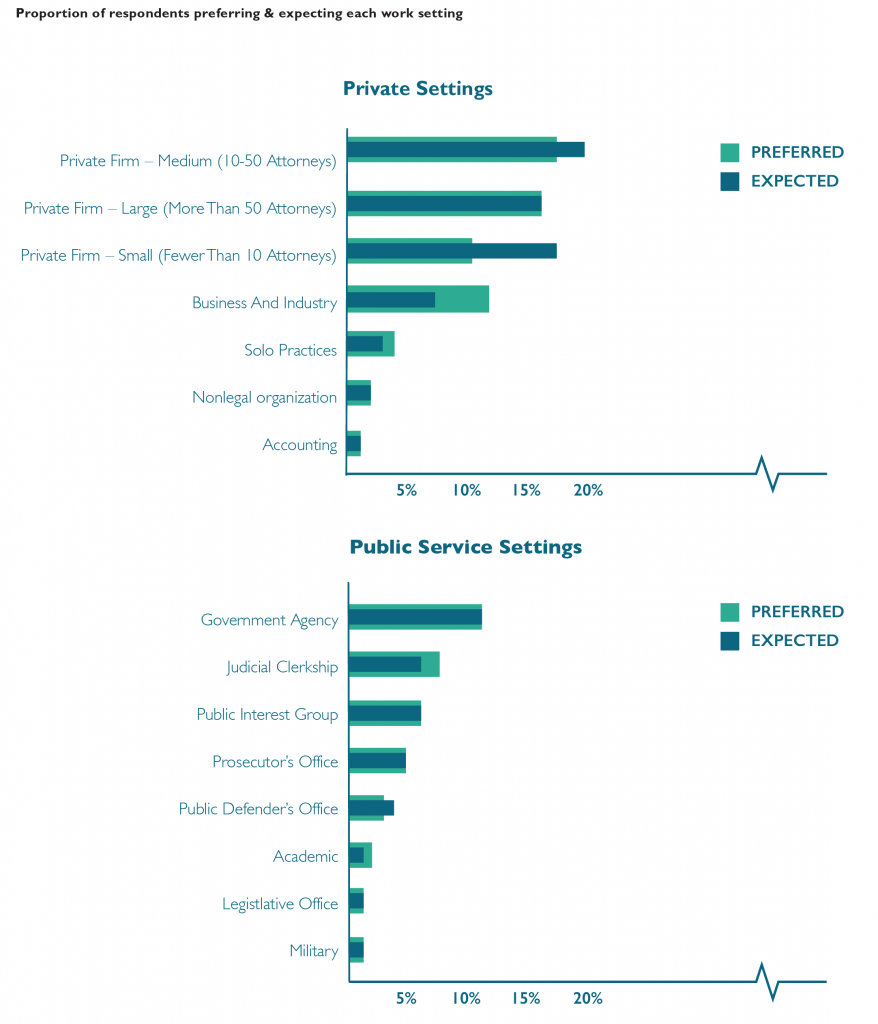

Seventeen percent of respondents would prefer to work in medium-sized law firms, making this category the most popular private setting and the most popular setting overall. Government agencies are the most popular public setting, with 11% of respondents indicating that preference. Medium-sized law firms are also the most commonly expected private work setting, accounting for 20% of respondents. Small law firms are the fourth most preferred private setting yet the second most common expected setting. Government agencies are the most commonly expected public service setting.

Forty-four percent of respondents indicate a different expected work setting than their preferred setting. Respondents who prefer to work in an academic setting are least likely to expect to work in that setting, with only about one-in-five matching preference with expectation. Respondents who prefer to work in large law firms or as prosecutors are most likely to also expect to work in those settings.

Forty-six percent of respondents who prefer one of the public service settings expect to work in a non-preferred setting, including one-quarter who expect to work in private settings instead. Forty-one percent of respondents who prefer one of the private settings expect to work in a different setting, but only 12% of students who prefer to work in a private setting expect to work in public service instead.

LSSSE Demographic Characteristics Reflect the U.S. Law Student Population

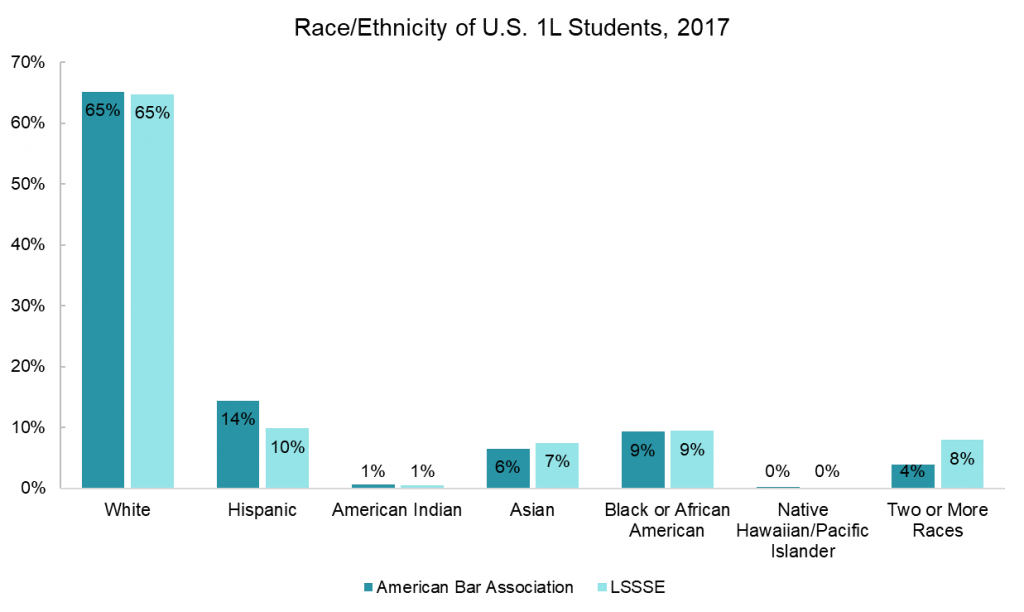

The Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) provides a treasure trove of information about the law school experience from the perspective of law students themselves. LSSSE partners with legal education scholars to provide access to de-identified data about topics ranging from student satisfaction to time usage to personal and professional development. Many researchers – particularly those interested in questions of diversity and equity – are interested in how closely the students surveyed by LSSSE reflect the gender and racial/ethnic composition of the entire law school population. To answer this question, we compared the self-reported gender and race of 2017 U.S. 1L LSSSE respondents to the 2017 matriculant gender and race/ethnicity aggregate data available from the American Bar Association (ABA).

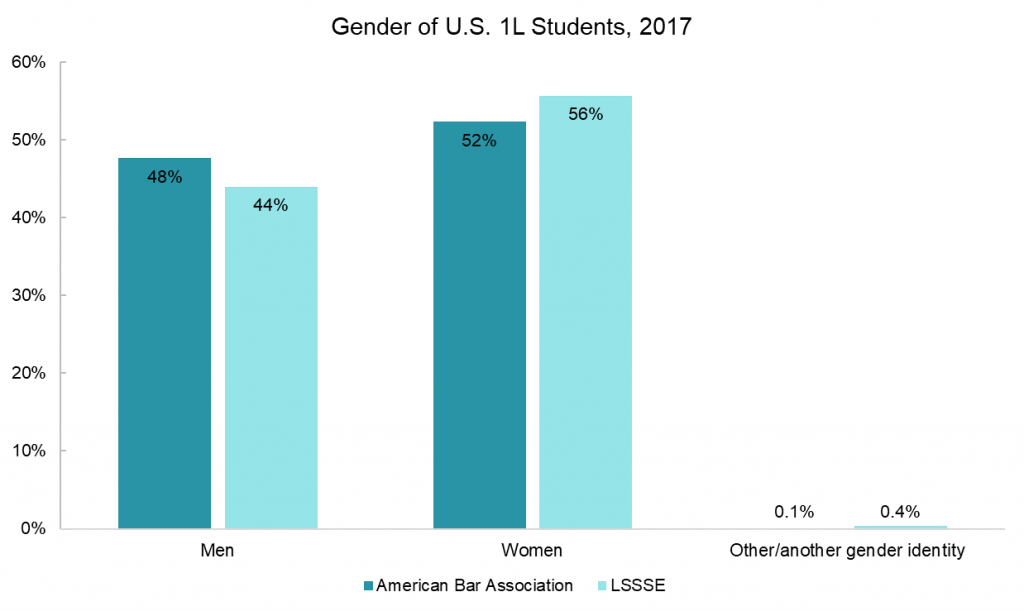

The ABA reported that slightly more women than men enroll in law school (52% vs. 48%). U.S. 1L LSSSE respondents in 2017 were similarly more likely to be female than male (56% vs. 44%). Although both the ABA and LSSSE collected data students identifying as “Other” (ABA) and “Another gender identity” (LSSSE), these individuals make up only a tiny fraction of the law student population (24 people according to the ABA and 22 people who responded to LSSSE).

The 1L students who responded to LSSSE in 2017 were also quite similar to the overall population of 1L students at all ABA-accredited programs in terms of racial/ethnic makeup. Sixty-five percent of both groups were white, nine percent were black or African-American, and around six percent were Asian or Asian-American. The ABA reported a slightly higher proportion of Hispanic students (14%) compared to the proportion of Hispanic LSSSE respondents (10%), and LSSSE respondents were more likely than the population of 1L students at ABA-accredited law schools to be multiracial (8% vs. 4%). However, the overall pattern of race/ethnicity frequency is quite similar among the two populations. Thus, LSSSE respondents tend to represent the demographic characteristics of law students in general.

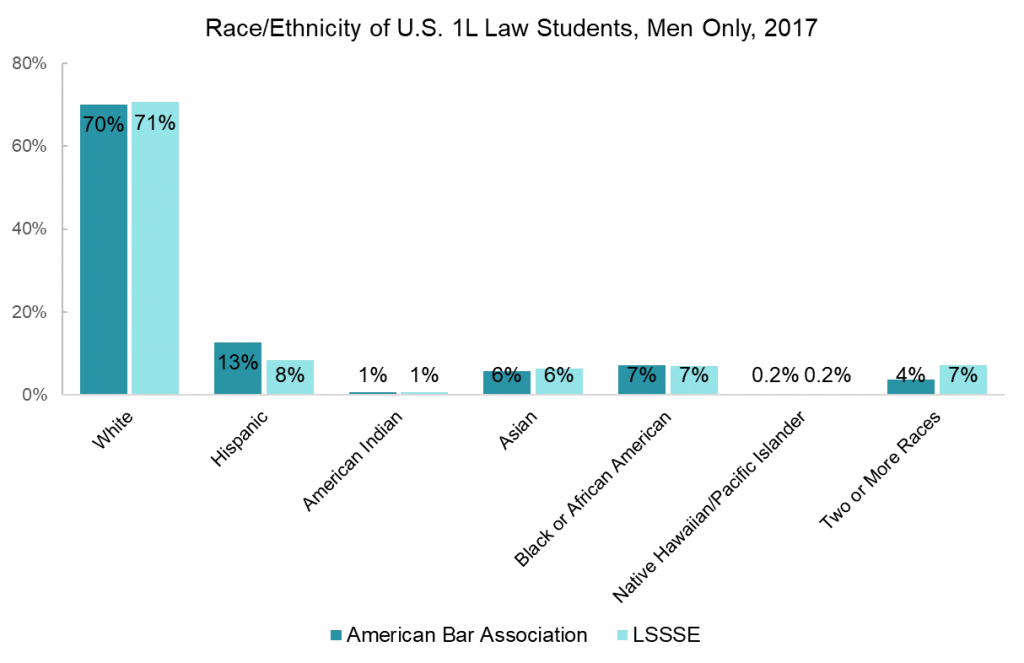

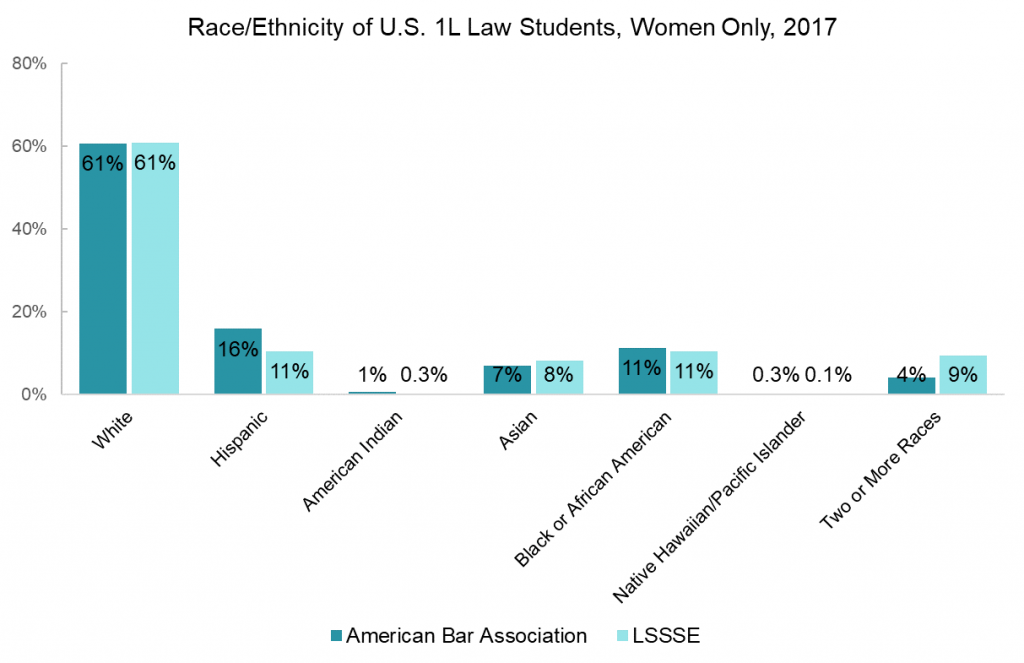

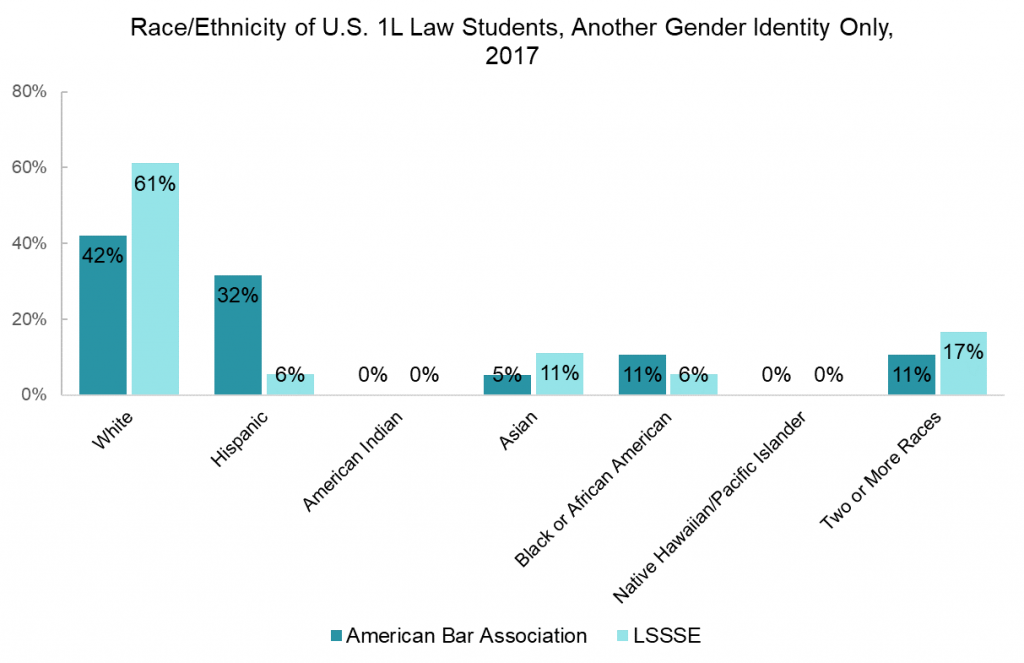

The ABA and LSSSE datasets also allow us to examine the intersection of gender and race/ethnicity among 1L students. Interestingly, a higher proportion of male law students than female students are white (70% vs. 61%). The general trends regarding the proportions of students from different racial and ethnic groups described across all students hold true for men and women when examined separately, but the same cannot be said for students of other gender identities, likely because this group is so small.

In the aggregate, LSSSE offers a representative sample of law students in terms of both race/ethnicity and gender identity, making it a great source of information about student engagement and the law school experience. Check out some of the publications using LSSSE research or contact us to discuss how a LSSSE data-sharing agreement might enhance your legal education research project.

Law Student Perceptions of Faculty

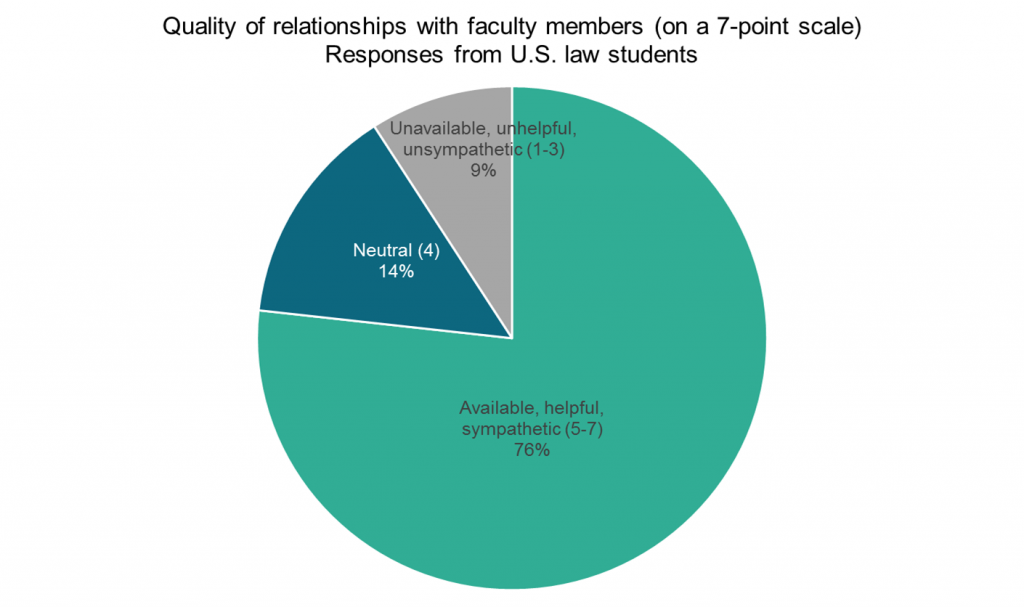

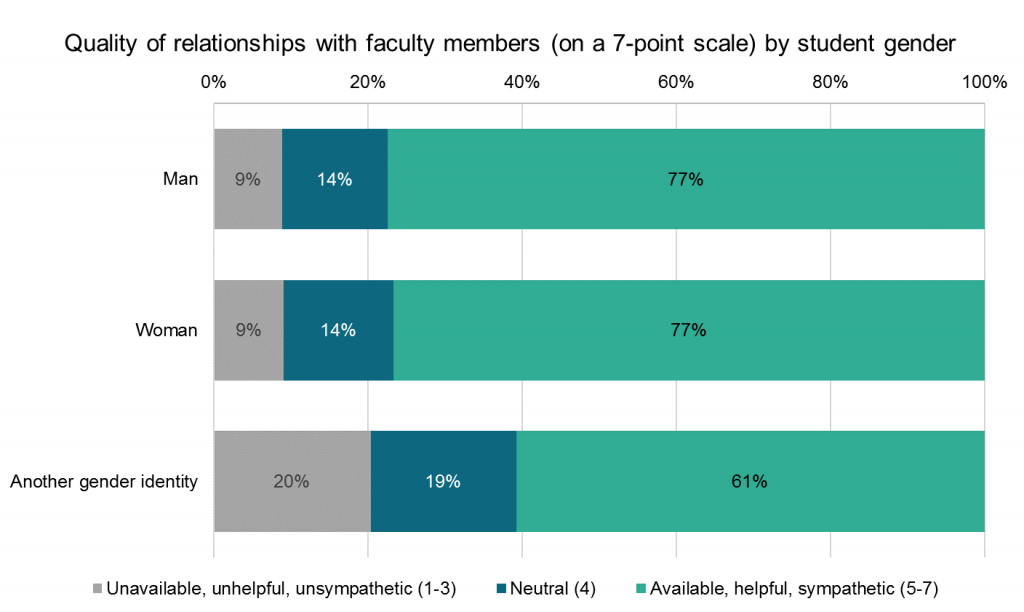

The Law Student Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) asks students about the quality of their relationships and interactions with law school faculty as a way of measuring whether students feel valued by others and engaged with the law school experience. As a group, law students tend to have positive perceptions of their instructors. In 2018, 76% of the 17,928 U.S. law students who responded to LSSSE rated their relationships with faculty as at least a “five” on a seven-point scale, where “one” was the perception of faculty as “unavailable, unhelpful, and unsympathetic” and “seven” was the perception of faculty as “available, helpful, and sympathetic.” Male and female students were pleased with their instructors at equal rates, although students of other gender identities were somewhat less satisfied, with only 61% rating their relationships with faculty a “five” or higher.

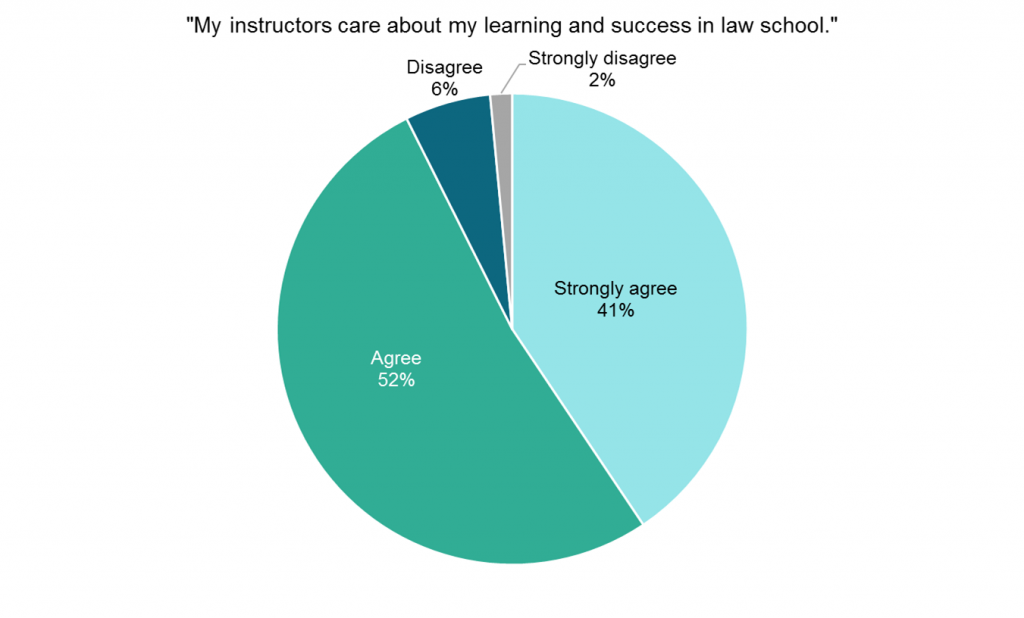

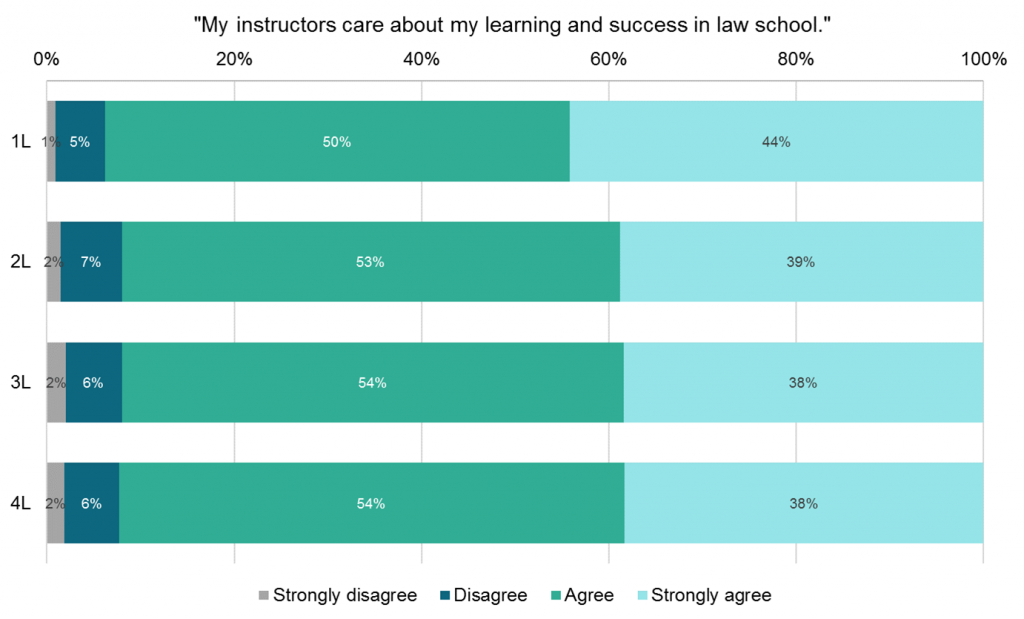

In 2018, a subset of 7,718 LSSSE respondents received the popular Learning Experiences and Professionalism (LEAP) module, which dives more deeply into students’ perceptions of both the law school community and their own readiness for legal practice. The vast majority of law school students (93%) agree or strongly agree that their instructors “care about my learning and success in law school.” Students in their first year of law school are most likely to strongly agree with this statement (44%), but overall there is not an appreciable drop in students’ sense that their instructors care about their law school experience across class years. Only 6-9% of students in any year of law school disagree or strongly disagree that their instructors care about them.

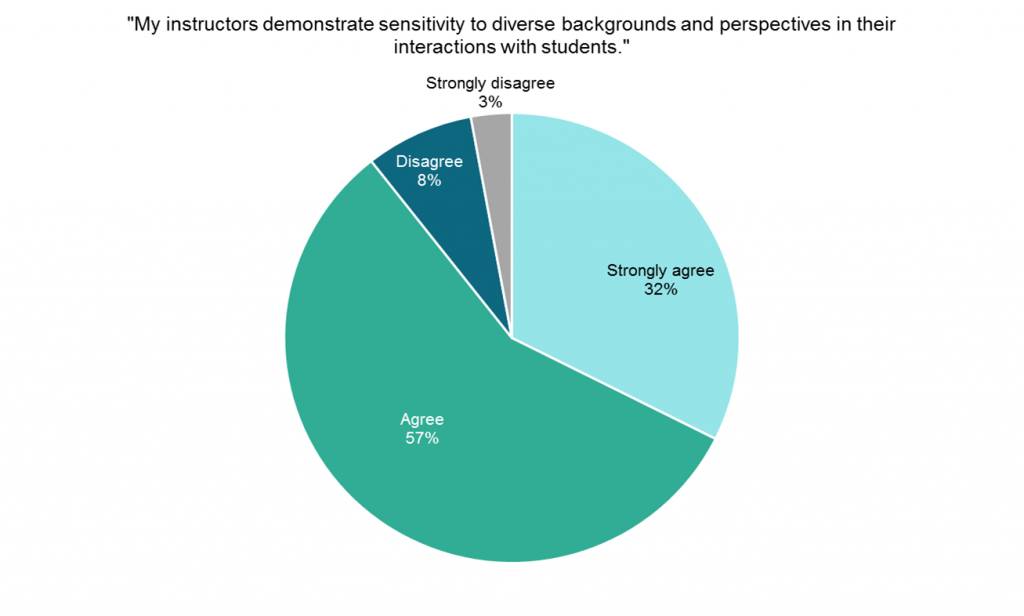

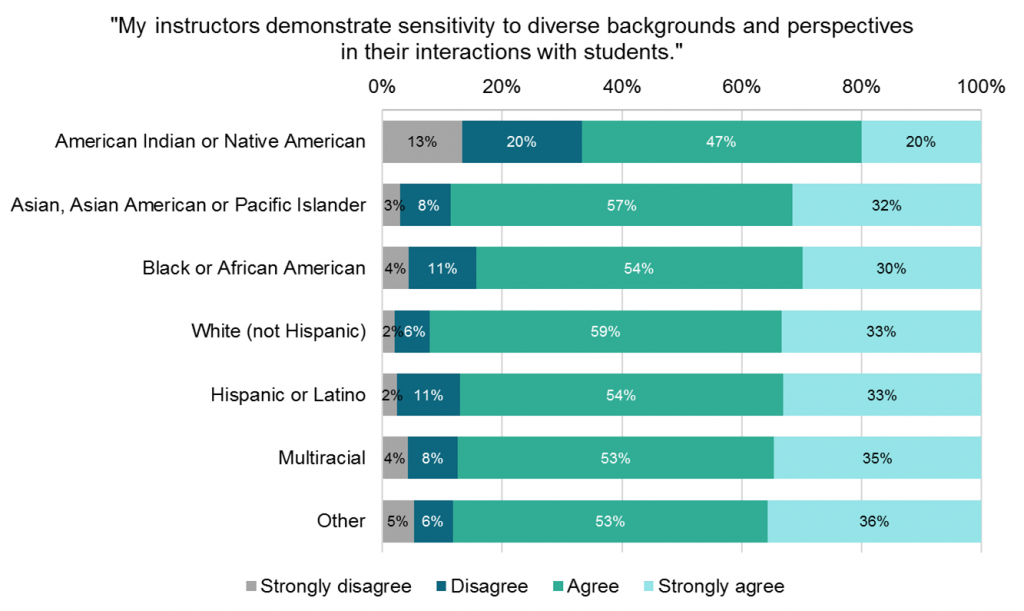

The LEAP module also asks whether student believe that their “instructors demonstrate sensitivity to diverse backgrounds and perspectives in their interactions with students." Among U.S. law students surveyed in 2018, 89% of students agree or strongly agree with this statement. There is some variation among students of different racial groups: 92% of white students agree or strongly agree that their instructors are sensitive to issues of diversity while only 67% of American Indian or Native American students share this viewpoint. This suggests that disparities still exist, particularly in how students of color perceive faculty attitudes toward diversity and how students from varying backgrounds are treated in the classroom.

Law Student Time Usage by Age

Attending law school can be a different experience for students at different life stages. Younger students who matriculate directly after receiving an undergraduate degree likely have different priorities and life experiences than older students who return to higher education after spending time in the workforce. We were interested in the academic and intellectual experiences of full-time 1L law students in the U.S. We also wanted to know how they spend their time outside the classroom. Our hope is that LSSSE data can help law schools understand the unique experiences and needs of different student populations based on age.

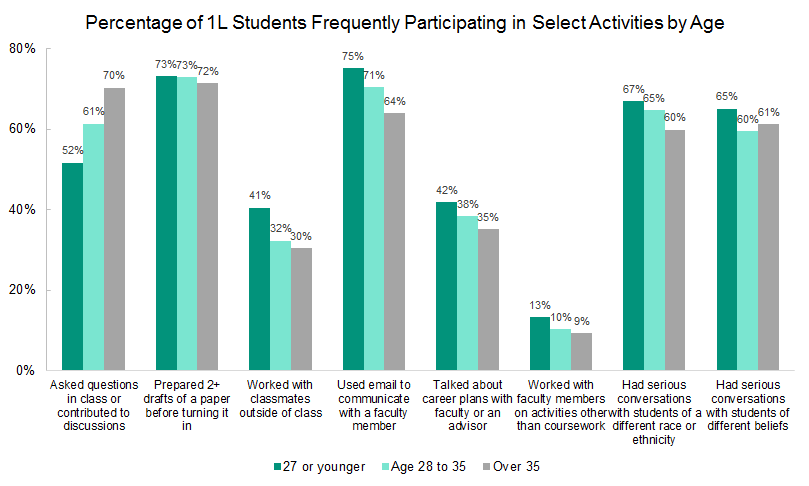

The academic experiences of younger and older students are quite different. Younger 1L students (age 27 or below) contribute less often to classroom discussions than their older peers. However, younger students are more likely to engage in email communication with faculty members and to talk about career plans with faculty or an advisor. Older 1L students (over age 35) were less likely to engage with students and faculty members outside of class. Older students were also generally less likely to have serious conversations with classmates who are different from them. However, most 1L students appear to invest heavily in their coursework regardless of age: almost three-quarters of students report frequently preparing multiple drafts of a paper before turning it in.

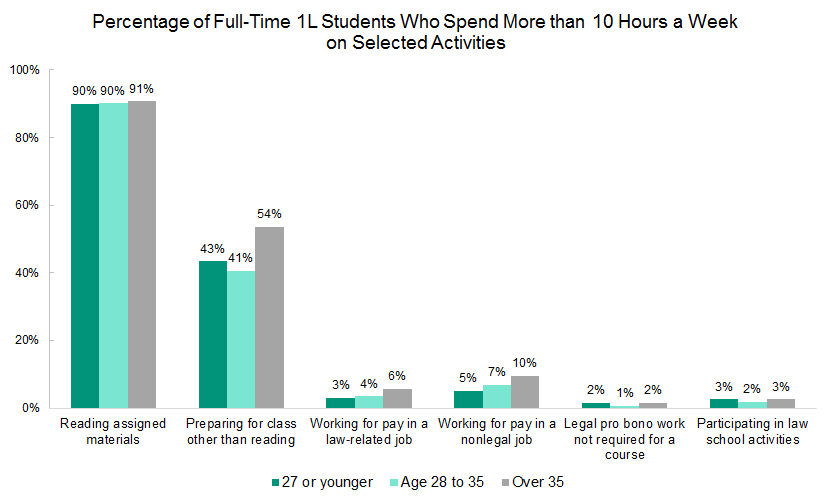

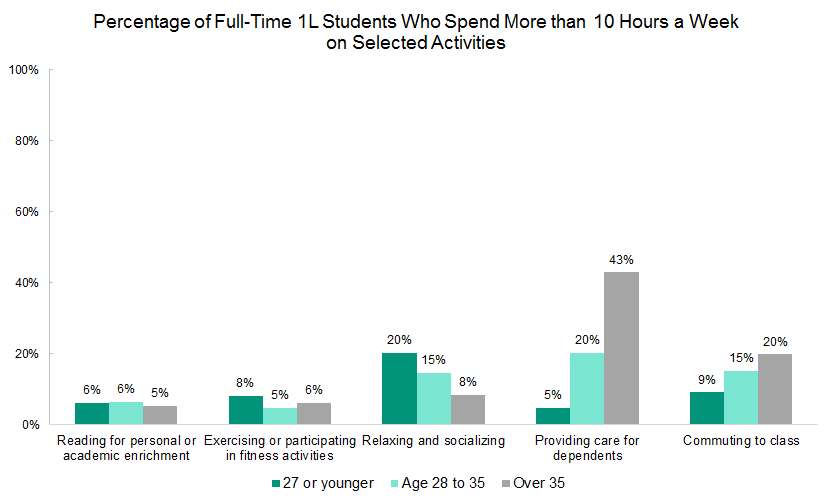

LSSSE also asks students to estimate how many hours they spend each week on various activities such as preparing for class, participating in law school activities, working for pay, socializing, and commuting to class. Different life circumstances necessitate different allocations of time and energy, and we see evidence of this among 1L students of different ages. We calculated the percentage of full-time 1L students in each age category (27 or younger, age 28-35, and over 35) who spend ten or more hours per week on each activity. Nearly all students (90%) spent more than 10 hours per week reading assigned materials, and a sizeable proportion spent more than 10 hours per week doing additional class preparation other than reading. This is particularly true for the oldest category of students. The youngest students spent more time relaxing and socializing than their older peers, although this disparity is likely accounted for by the extra time that older students spent working and providing care for dependents. The oldest group of students were also significantly more likely to have spent more than 10 hours per week commuting compared to the youngest students (20% vs. 9%), perhaps because their additional outside responsibilities made relocating closer to their law school less feasible. Finally, although the majority of full-time 1L law students spent some time participating in law school-sponsored activities each week (65%), most spent between one and five hours per week. Only a tiny fraction of each age group devoted more than ten hours per week to these endeavors.

Classroom participation by gender identity

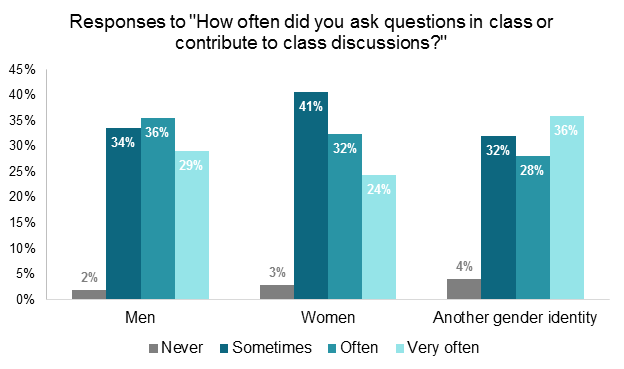

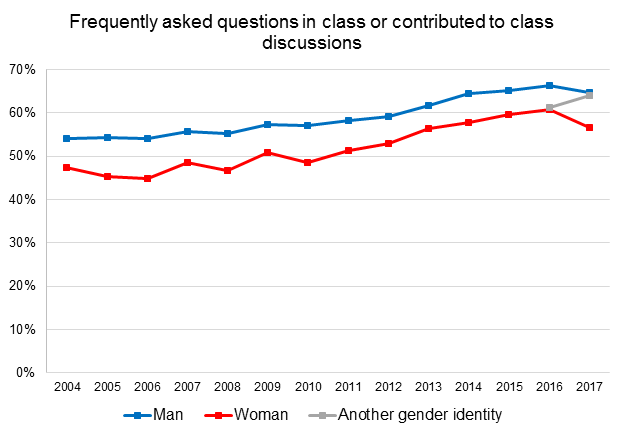

The law school classroom is a hotspot of student engagement. Historically, classroom observations and self-report data have shown that male voices tend to be heard more often than female voices in the law school classroom. How do U.S. law students rate the frequency of their own participation? The Law School Survey of Student Engagement asks students to report how often they asked questions in class or contributed to class discussions in the most recent school year, using the options “never,” “sometimes,” “often,” or “very often.” We found that in 2017, frequent class participation was indeed higher among male students than female students.1

Combining the students who participate “often” and “very often,” we see that this gender gap has existed every year that LSSSE was administered, going back to the inaugural survey in 2004.

Interestingly, although the overall percentage of respondents who frequently participate in class has fluctuated over the years, the gap between male and female participation has stayed fairly constant. LSSSE added a third gender option in 2016, which means that future data sets will give us a more nuanced understanding of the law school experience for students of all genders.

1 Independent samples t-test, t=10.0, p<0.001, d=0.2.

Law School Service Use: LSSSE 2017

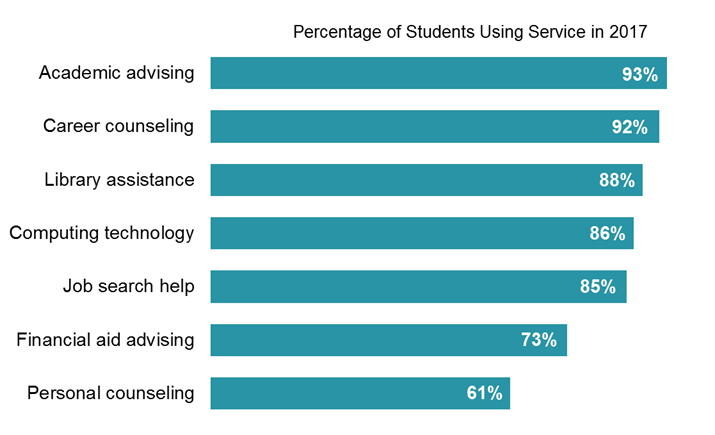

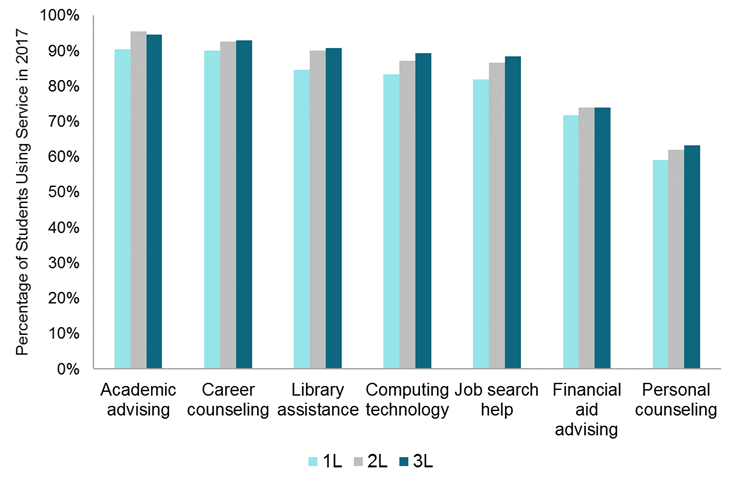

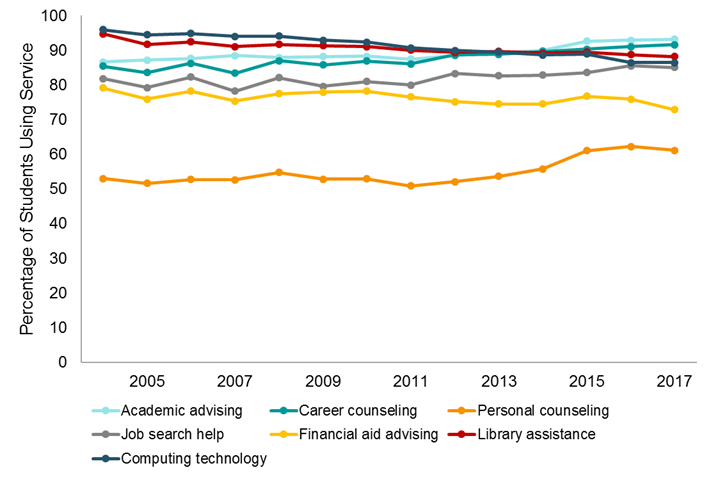

Law schools offer services to support student success both during law school and after graduation. For seven core law school services, LSSSE asks students to either rate their satisfaction or to indicate that they did not use a particular service during the current school year. Student satisfaction levels can help guide efficient resource allocation, and non-use rates can highlight services that are overlooked or underused.

Service use was quite high among U.S. law students in general. The greatest demand was for academic advising services, which were used by 93% of students. Nearly as many students (92%) sought career counseling. Personal counseling was the least used resource, with only 61% of students giving a satisfaction rating for this service.

Among law students who answered all seven service-use questions, the average number of services used was 5.8. Part-time students used an average of 5.1 services, which was less than full-time students, who used 5.9 services on average.

Each service showed slightly higher usage among 2L and 3L students than among 1L students. This makes intuitive sense for certain services (such as job search help) that may be more relevant during later stages of the law school experience. However, this finding is somewhat surprising for more general student services such as library assistance and computing technology.

Finally, service usage has fluctuated somewhat since LSSSE started measuring student satisfaction in 2004. Use of personal counseling is trending upward, with 53% of students using this service in 2004 and 61% of students using it in 2017. Conversely, use of computing technology has decreased markedly, with 96% of respondents reporting using law school technology in 2004, compared to 86% in 2017.

LSSSE Annual Results 2006-2016: What Has Remained the Same?

In the our last post, we re-visited the LSSSE 2006 Annual Results (pdf) to look at how the trends identified as “Disappointing Findings” in 2006 compare to the results from the LSSSE 2016 survey. Today we will look at what patterns in law student engagement have remained the same.

What has not changed in the last decade?

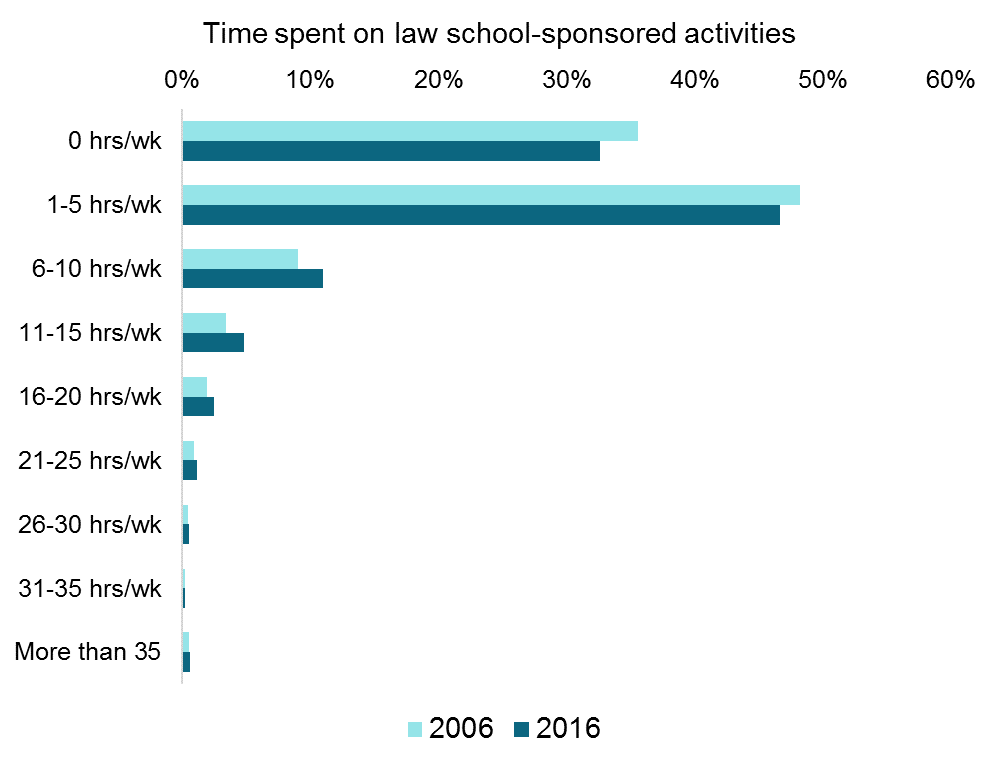

Although participation in public service has increased among law students, participation in law school-sponsored organizations (clubs, journal, committees, moot court, etc.) among all law students has stayed relatively stable. More than a third of law students (36%) spent no time during the week participating in these organizations in 2006; in 2016 the non-participation rate dipped only slightly to 33%.

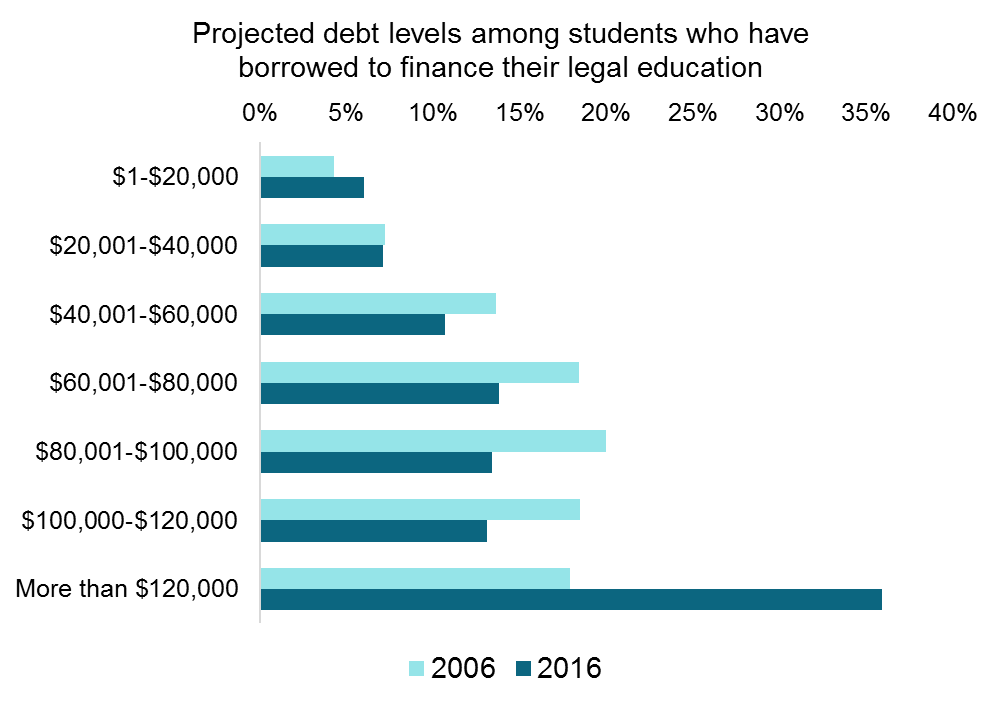

Surprisingly, at first glance the student debt load appears unchanged from 2006 to 2016. In 2006, the LSSSE Annual Results noted that of those students at U.S. law schools who incurred debt related to their legal education, 75% will owe more than $60,000 by graduation. In 2016, that number was 76%. However, if we look at the distribution of debt by category, we see a remarkably different picture. In 2006, survey respondents selected their projected debt law school debt using the following categories:

- $0

- $1-$20,000

- $20,001-$40,000

- $40,001-$60,000

- $60,001-$80,000

- $80,001-$100,000

- $100,000-$120,000

- More than $120,000

In 2016, those categories were expanded to more accurately capture higher debt levels among law students:

- $0

- $1-$20,000

- $20,001-$40,000

- $40,001-$60,000

- $60,001-$80,000

- $80,001-$100,000

- $100,000-$120,000

- $120,001-$140,000

- $140,001-$160,000

- $160,001-$180,000

- $180,001-$200,000

- More than $200,000

If we collapse the higher categories from the 2016 data into a single “More than $120,000” category to compare with the 2006 data, it becomes clear that student loan debt has become much more onerous for law students in 2016 compared to 2006, despite the fact that the overall percentage of students who owe more than $60,000 has remained unchanged.

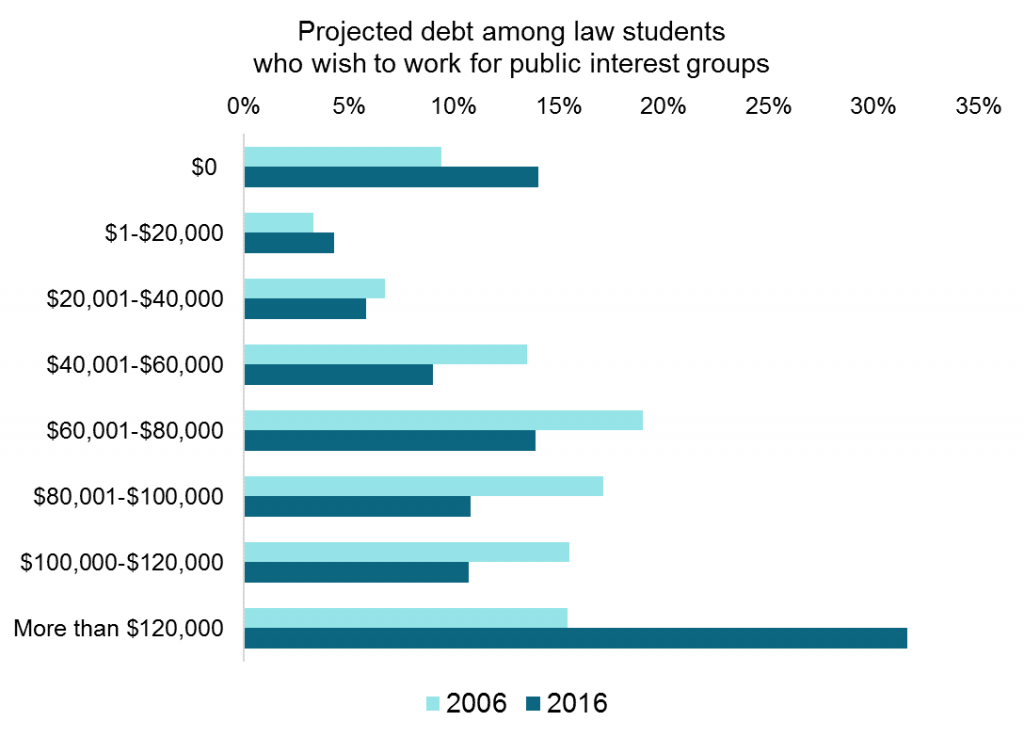

The pattern is similar among students who wish to work for public interest organizations, which generally pay less than other law careers. In 2006, the LSSSE Annual Results warned that 67% of aspiring public interest lawyers expected to owe more than $60,000 upon graduation. In 2016, the exact same percentage (67%) of students hoping to work for public interest organizations reported expecting to owe more than $60,000, but the percentage of students who wish to work for public interest organizations and who will owe more than $120,000 has approximately doubled.

The LSSSE 2016 results show that while the percentage of students who will owe more than $60,000 has not changed between 2006 and 2016, students in the highest borrowing categories are taking on significantly heavier financial burdens than students in 2006.

LSSSE Annual Results 2006-2016: What Has Changed?

The 2006 LSSSE Annual Results (pdf) targeted several potential areas of improvement for law student engagement. In particular, the report highlighted somewhat low participation in pro bono and volunteer work and a relative lack of time spent on law school-sponsored activities. The report also noted a high student debt load, particularly among students who planned to work for public interest organizations. We used the 2016 LSSSE data to see what has changed and what has stayed the same over the last ten years. In this first of two posts, we will describe what has changed in the last decade.

What has changed in the last decade?

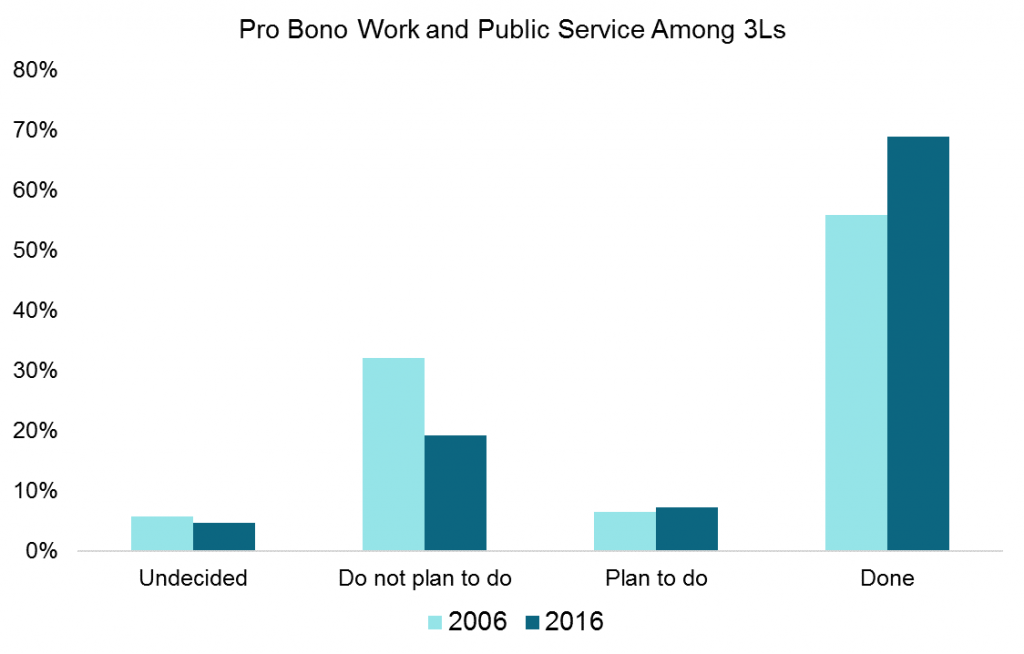

Participation in public service among law students has increased substantially. In 2006, nearly a third of 3L respondents (32%) reported that they had not done any pro bono or volunteer work during law school and had no plans to do so. In 2016, only 19% of 3L respondents reported having not done any pro bono work or public service and having no plans to do so. In terms of weekly time usage, three-quarters (77%) of 3L respondents in 2006 spent no time during the week on legal pro bono work not required for class. By 2016, that number had declined to 66% of 3Ls.

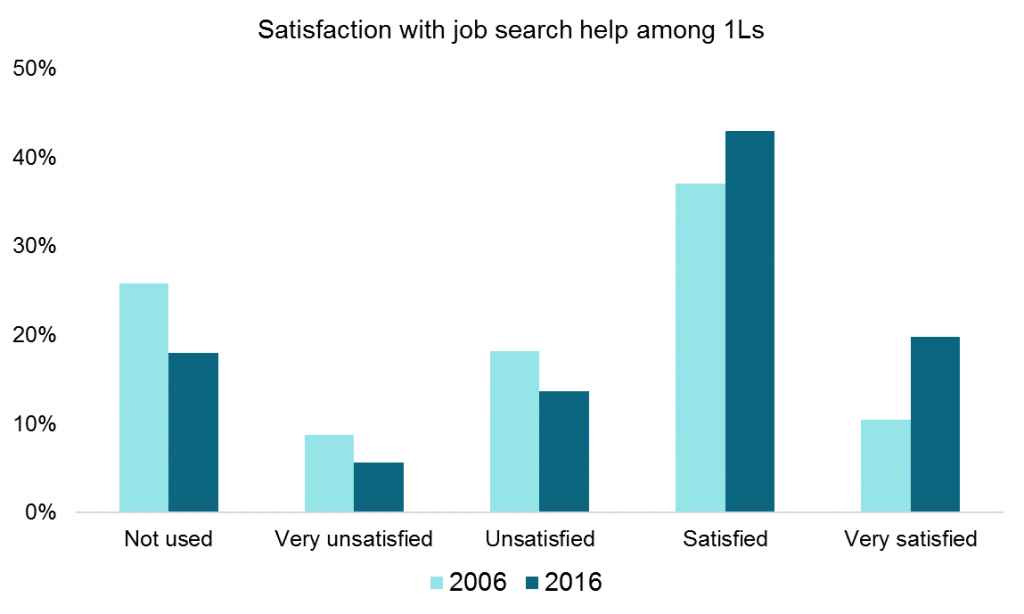

More law students are using job search assistance earlier in their legal educations, perhaps due to increased awareness of changes in the legal employment landscape. One in four 1Ls (26%) reported never using job search assistance at their law school in 2006. In 2016, that number was less than one in five (18%).

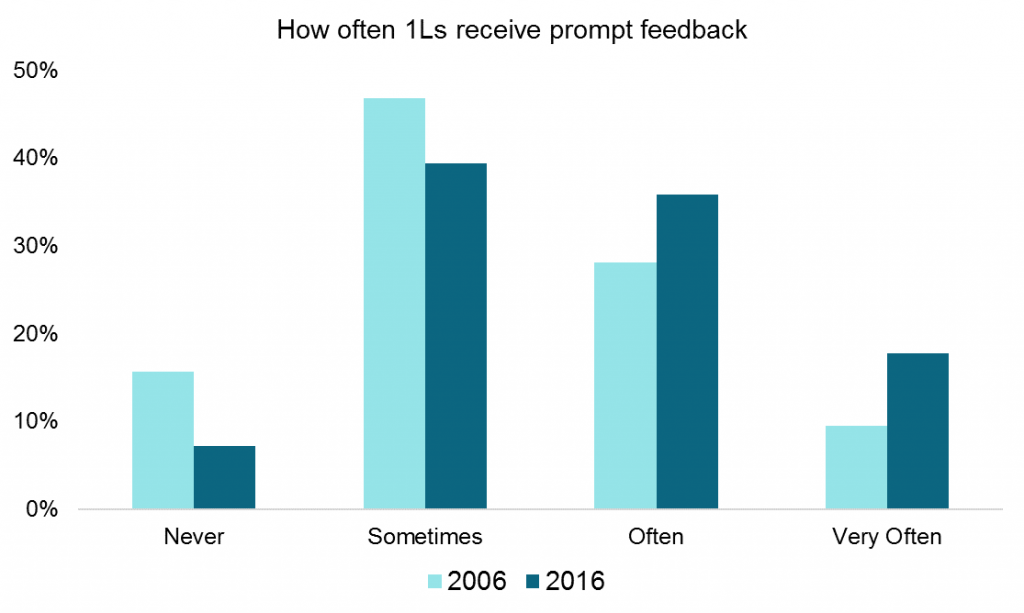

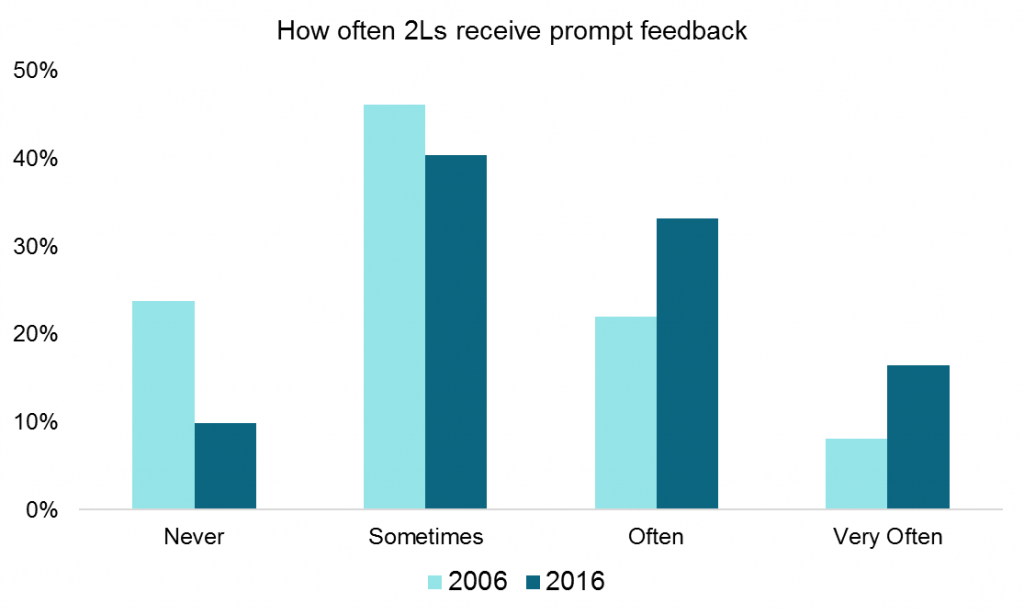

Law school faculty also appear to be more diligent about giving timely feedback to students. In 2006, about 15% of 1Ls and 24% of 2Ls reported never receiving prompt feedback from faculty members. In 2016, only 7% of 1Ls and 10% of 2Ls said they never received timely feedback from faculty.

Overall, law school students in 2016 showed more participation in public service and greater satisfaction with faculty feedback. This suggests progress in ameliorating some of the concerns identified by the 2006 LSSSE Annual Report. In our next post, we will look at which of the findings from 2006 are still areas ripe for improvement today.

LSSSE Annual Results 2016: Scholarships and the Law School Experience (Part 5)

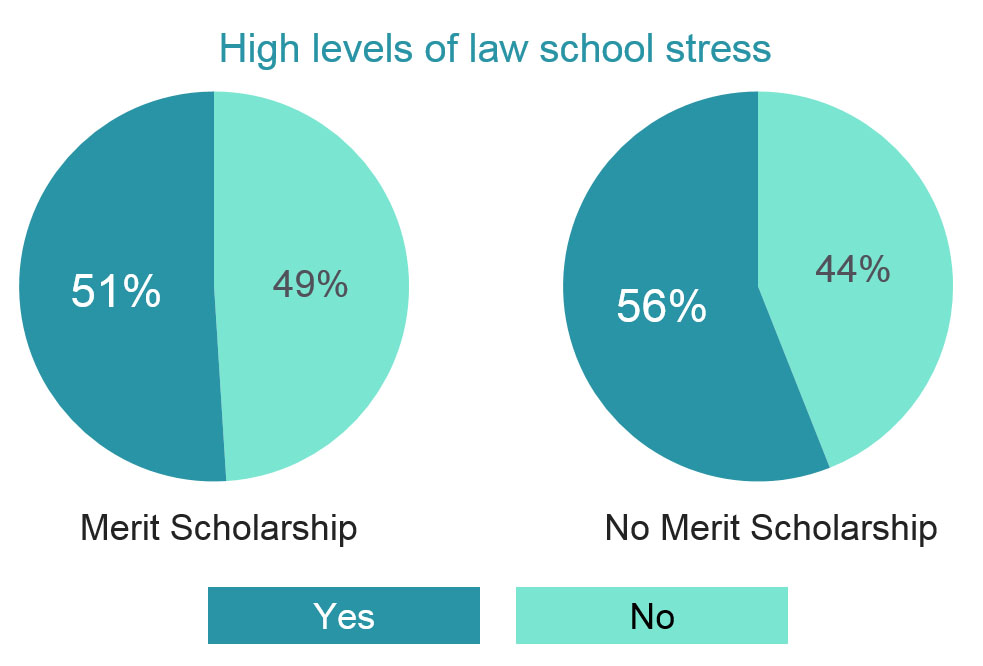

This is the fifth installment in a series of five posts based on data from the 2016 LSSSE survey administration and the 2016 Annual Report. The LSSSE 2016 Annual Report highlights inequities in scholarship policies and the consequences for student loan debt. In this post, we examine how scholarship recipients and non-recipients rate their stress levels and overall satisfaction with law school.

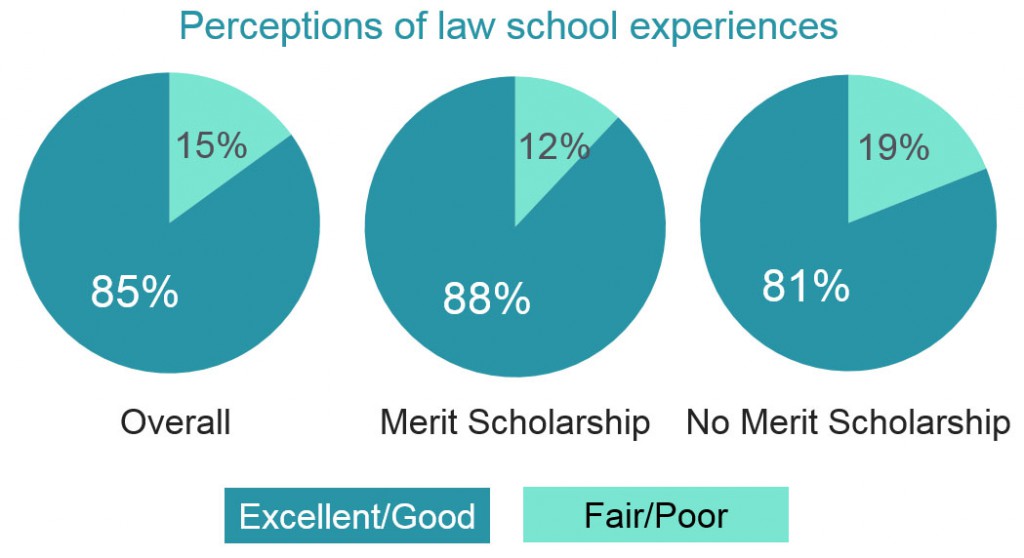

Law students tend to have favorable perceptions of their law school experiences. Eighty-five percent of LSSSE respondents rated their law school experiences “good” or “excellent.” Receipt of a scholarship was associated with even higher satisfaction. Eighty-eight percent of respondents who received merit scholarships rated their experiences favorably, compared to 81% of respondents who did not receive merit scholarships. Similar trends persisted across racial and socioeconomic classifications, with the most intense effects being among black and Latino respondents.

A subset of 2,256 respondents were surveyed about the extent and nature of law school-related stress they experienced. Among this group, the receipt of a merit scholarship was associated with stress levels. Fifty-one percent of respondents who received merit scholarships reported high levels of law school stress, compared to 56% of respondents with no merit scholarships.