Annual Results 2018: Relationships Matter – Student Relationships

Decades of research on student engagement and student learning demonstrate the importance of peer interactions. Engaging with classmates in meaningful ways contributes to a deeper sense of belonging and enhances understanding of classwork, leading to better academic and professional outcomes (Hurtado & Carter, 1997; Pascarella & Terenzini, 2005; NSSE, 2013).

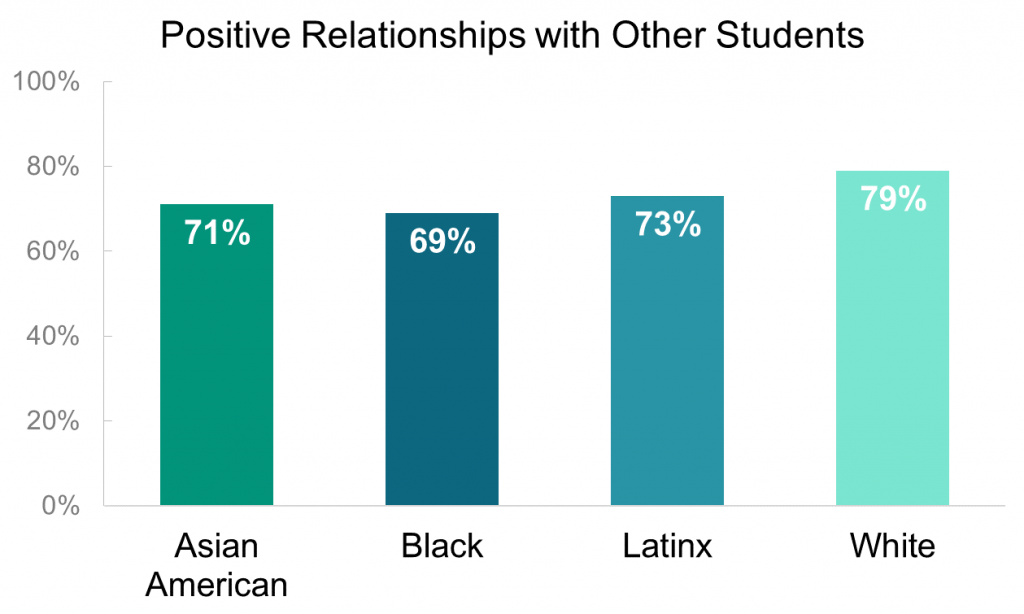

Although law school is an inherently stressful and anxiety-producing endeavor, the vast majority of students (76%) report that their peers are friendly, supportive, and contribute to a sense of belonging. There are noticeable variations by race/ethnicity. White students are most likely to report positive relationships with peers (79%), as compared to Black (69%), Asian American (71%), and Latinx (73%) students.

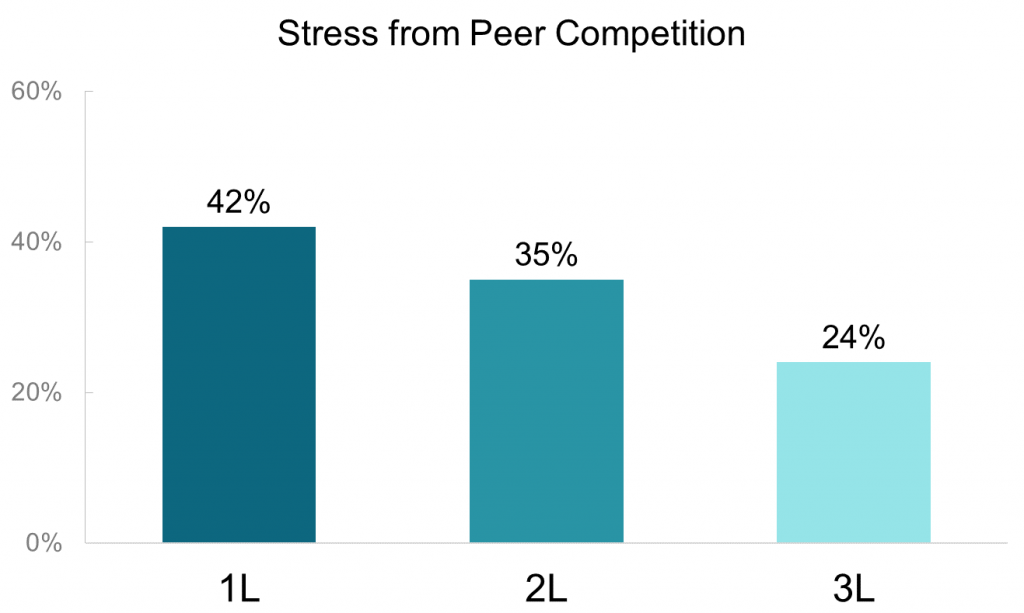

The Student Stress Module examines law student stress and anxiety—their sources, impact, and perceptions of support offered by law schools to manage stress and anxiety. One question asks directly about various sources of stress and anxiety that students may face in school. High percentages of students report that academic performance (77%) and academic workload (76%) produce stress or anxiety, but competition amongst peers does not create or magnify these feelings for most students. Students report that competition amongst peers is most significant during the first year of law school but sharply declines each year. Forty-two percent of 1L students report that peer competition is a source of stress or anxiety. By the third year of law school that number drops to 24%.

Annual Results 2018: Relationships Matter – Advising

A majority of students are pleased with the quality of advising and their relationships with administrators:

- 69% are satisfied with academic advising and planning.

- 66% are satisfied with career counseling.

- 64% are satisfied with job search help.

- 70% are satisfied with financial aid advising.

- 68% report that administrative staff are helpful, friendly, and considerate.

The quality of relationships with advisors and administrators is both positive and relatively consistent across race, gender, and year in school. Seventy percent of 1L students (and 67% of 2Ls and 3Ls) report that administrative staff are helpful, considerate, and flexible. Seventy-nine percent (79%) of students consider at least one administrator or staff member as someone they could approach for advice or guidance on managing the law school experience. Higher percentages of Black students (87%) rely on these relationships than students from other racial backgrounds (79% for Asian American, white, and Latinx students).

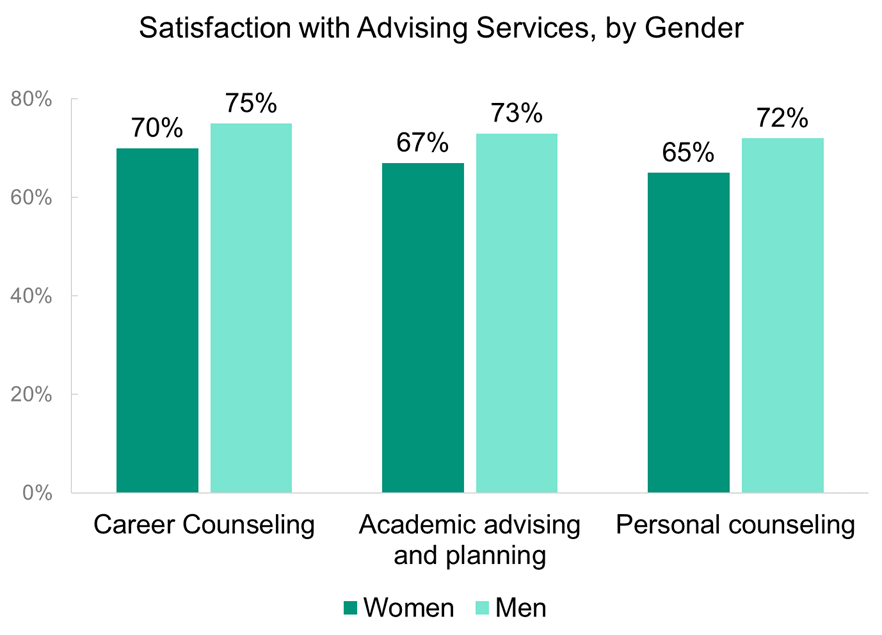

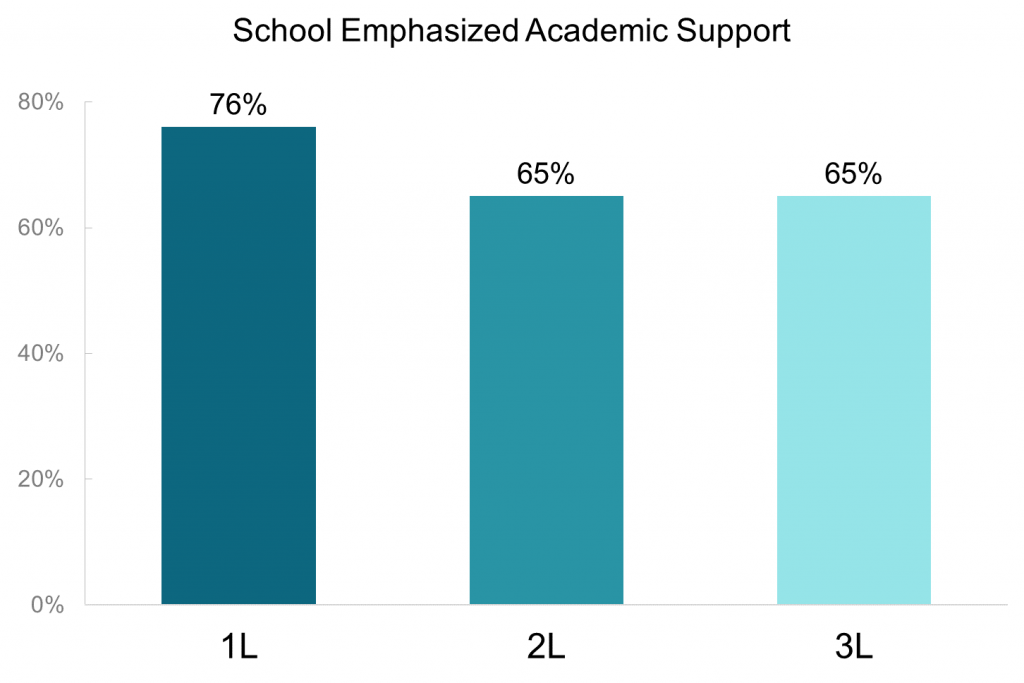

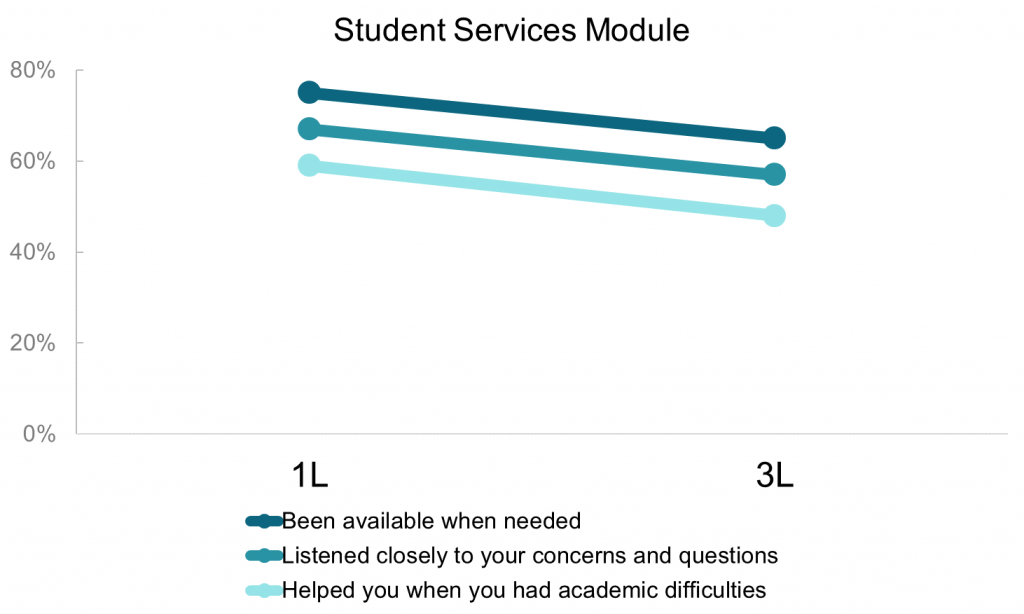

Interactions with academic support personnel drive whether a student would choose to attend the same law school again as well as overall satisfaction with their law school experience. Though students report positive relationships with administrative staff, satisfaction with advising services is less consistent and more varied across race/ethnicity, year in school, and gender. Sixty-nine percent of all respondents report that their law school provides the support they need to succeed academically, with higher perceptions of support among 1L students. Similarly, academic advising, career counseling, and job search help are key support services that students appreciate greatly when they begin law school, though they are more dissatisfied as graduation nears.

Annual Results 2018: Relationships Matter - Student-Faculty Interaction

Faculty, administrators, and classmates are key ingredients to law student success. These relationships serve as important ties to the law school and impact student satisfaction, sense of belonging, and academic and professional development. This year’s annual report explores relationships and examines the nuances of the impact they have on law students.

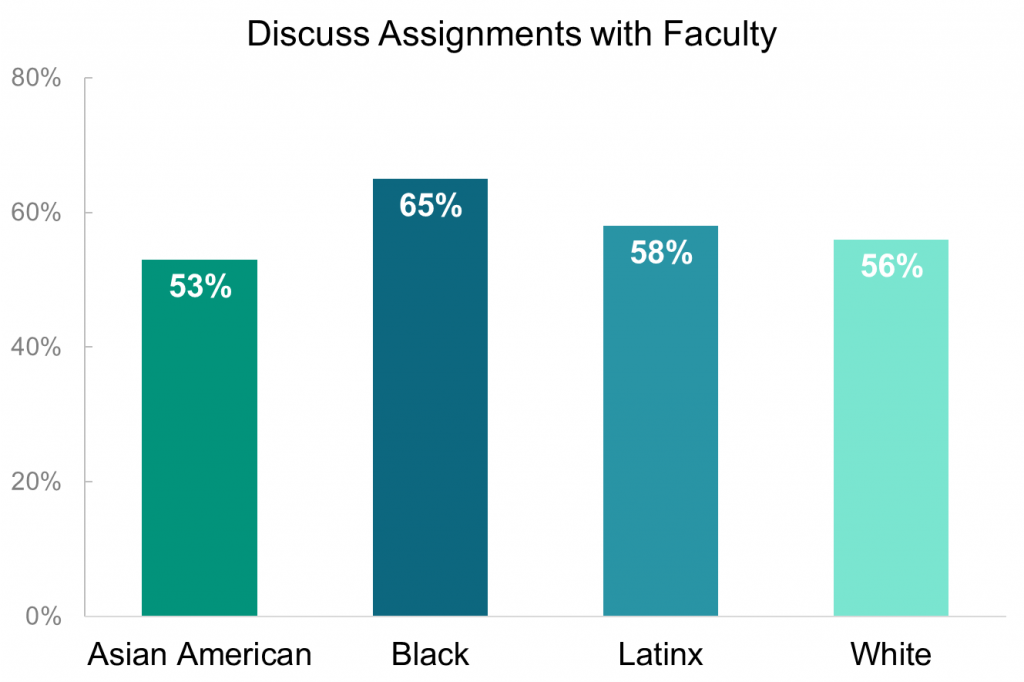

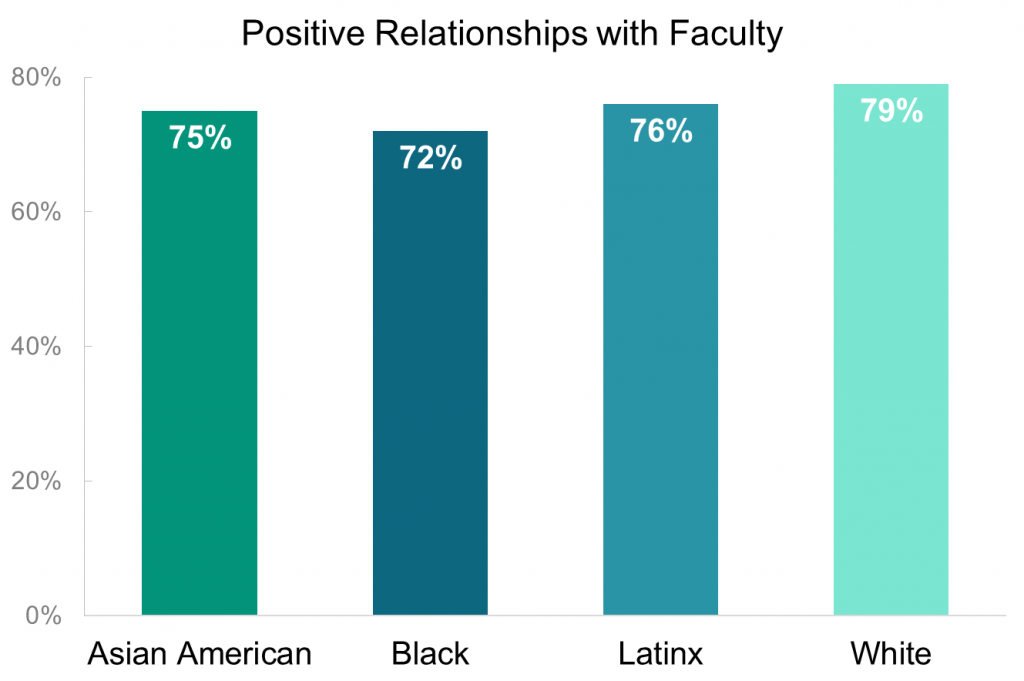

The vast majority of students (76%) report positive relationships with faculty, including interactions both in and out of the classroom. Meaningful interactions vary across student demographics, with notable race/ethnic differences. On multiple dimensions Black and Latinx students report more engagement and interaction with faculty than white and Asian American students. For instance, while a majority of all law students (57%) discuss assignments with faculty “often” or “very often,” 65% of Black students do so, the highest of any racial or ethnic group, followed by 58% of Latinx students, 56% of white students and 53% of Asian American students.

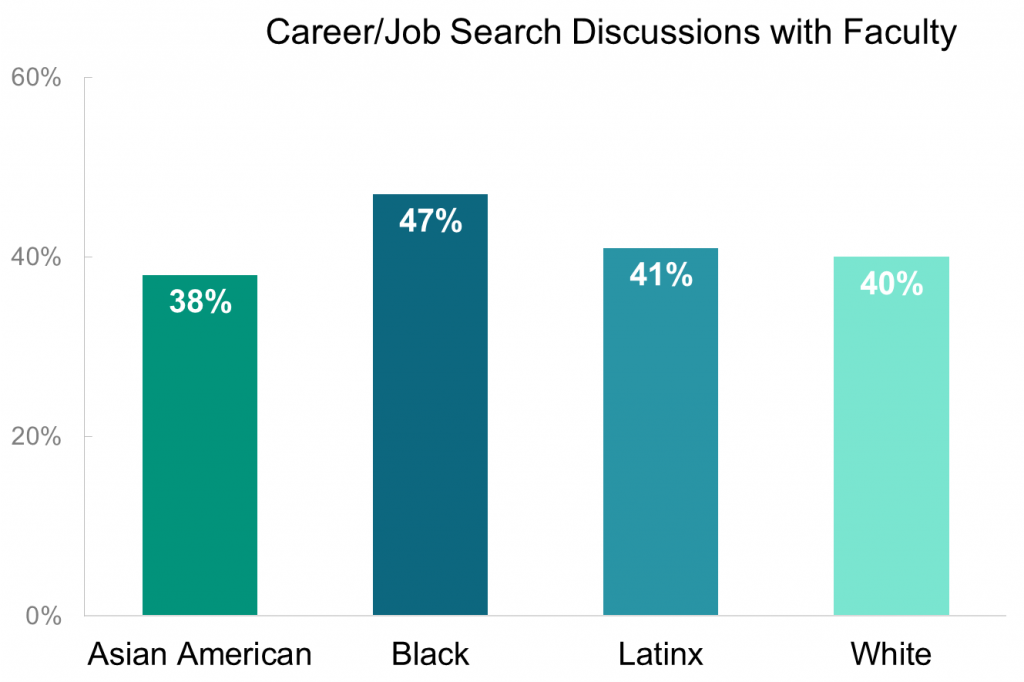

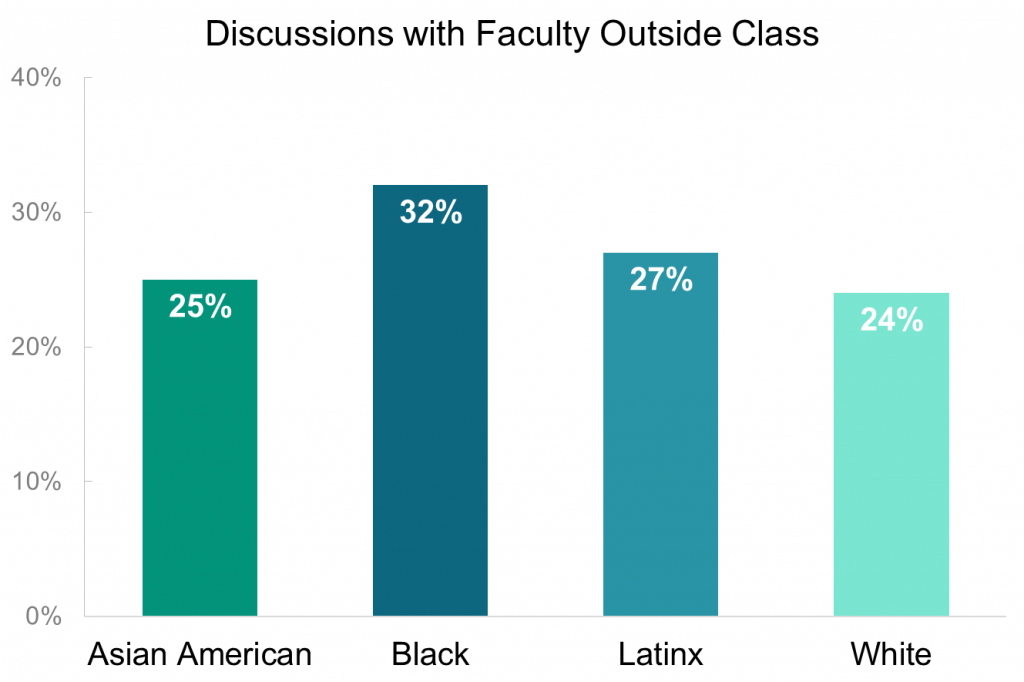

The pattern of Black and Latinx students enjoying higher rates of engagement with faculty persists across multiple dimensions. For example, Black students (47%) are more likely to discuss career or job search with faculty than Latinx (41%), white (40%), or Asian American (38%) students. Black and Latinx students are also more likely to talk with faculty outside of class. The vast majority of students find faculty available, helpful, and sympathetic. Interestingly, this sentiment does not directly track interaction with faculty, as a higher percentage of white students report favorable relationships with faculty than Black and Latinx students.

Guest Post: Getting to Excellent

Evan Parker, PhD

Evan Parker, PhD

Founder

Parker Analytics, LLC

Law school administrators operate in an environment that Dean Camille A. Nelson calls “relentlessly competitive” (See Nelson, “Towards Data-Driven Deaning,” LSSSE, August 22, 2019.) With students taking on sizable debt and an increasingly uncertain legal job market, it’s more important than ever that school administrators and faculty find ways to maximize the value of the law school experience.

What should they do to maximize the student experience? Conveniently, we can ask the students. More precisely, we can study students’ views of their law school experience as captured by the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE). One question on the survey asks, “How would you evaluate your entire educational experience at your law school?” LSSSE participants respond with one of four options: Excellent, Good, Fair, or Poor. Using a statistical model, we can identify what factors most strongly differentiate students who say their experience in law school was “Excellent.”

As a rich professional survey with extensive coverage of student issues, LSSSE lets us examine a number of possible drivers of student satisfaction with law school, and highlight those factors that seem to matter the most. I view this as evidence into what students want—and thus, what administrators looking to maximize value should work hard to deliver.

In the analysis to follow, the factors that most strongly predict an “Excellent” response—the top “value differentiators”—are within reach of every law school administrator, albeit addressing these factors requires hard work. In broad terms, this student-driven data indicates that schools must do three things well:

- Build and sustain relationships among students, faculty and professional staff;

- Provide first-rate advising, career counseling and personal support; and

- Develop a broad curriculum that instills work-related knowledge.

Analyzing the Law School Experience

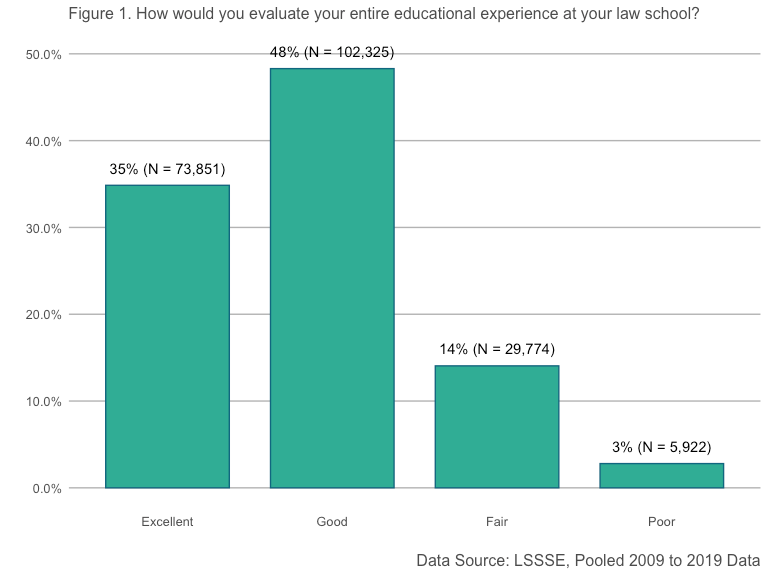

In this analysis, we’ll consider pooled LSSSE data over the 2009 to 2019 period. Figure 1 reports the four responses to the “entire experience” question, illustrating the distribution in percentage terms. Number of students per response is listed in parentheses.

Over the past decade, about one-third of LSSSE participants said that their entire law school experience was “Excellent” (35%). A near-majority of students viewed their law school experience as “Good” (48%), and the remainder were less positive (Fair = 14%, Poor = 3%).

We can use a statistical model to identify factors that are most strongly associated with an excellent law school experience. With more than 60,000 complete survey responses (i.e., 60,000 surveys have complete data), it’s straightforward to perform an exploratory analysis—one that includes all possible inputs into the model using the standard battery of LSSSE questions, 2009 to 2019—82 questions in total.[1] In a sample this large, the fact the model returns information about “statistical significance” is not so meaningful, since most of the factors will reach a level of significance. What is meaningful in the model, however, is its ability to produce “appropriate comparisons” between types of students—comparisons which isolate the importance of specific LSSSE factors by revealing the expected differences in students’ perceived law school experiences. For the purpose of this post, we’ll compare student responses that are typical (at the mean) versus responses that are very favorable (+2 standard deviations above the mean), and all else equal.

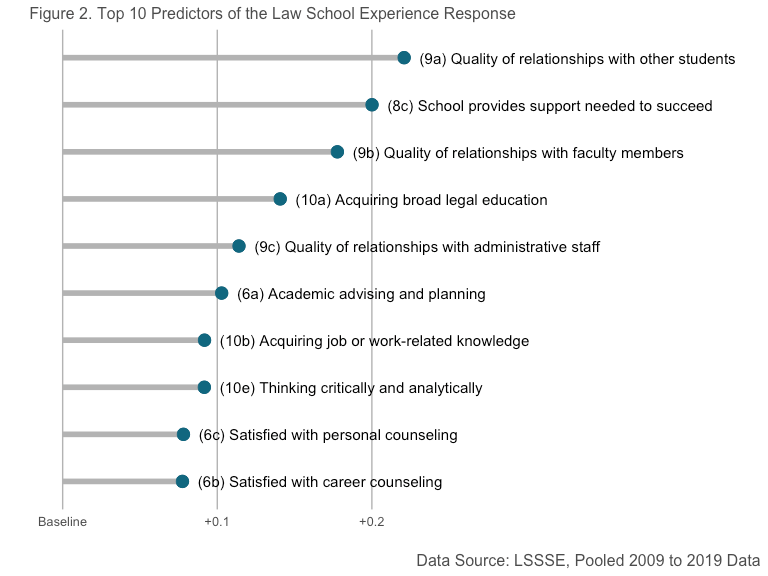

Figure 2 reports the top 10 positive predictors of the law school experience response. Reported values are the model-based differences between a typical baseline response (mean) and a very favorable (mean +2 s.d.) Scanning across the items, the three general themes involve (1) interpersonal relationships, (2) perceptions of support, and (3) features of the law school curriculum.

Quality of Relationships. The strongest positive differentiator is question (9a), the quality of relationships with other students. On this item, LSSSE asks students whether their relationships with other students are unfriendly or friendly using a 1 to 7 scale. So, at schools where students report above average friendliness among their peers, they are also more likely to view their law school experience as excellent. The same is true for relationships with faculty (9b) and administrative staff (9c), who are evaluated in terms of their availability and helpfulness, respectively.

Counseling and Support. A second set of factors that are strongly positively related pertain to students’ perceptions of support. This is the case in general per the importance of (8c), about the school’s ability to provide necessary support to succeed (1 = Very Little, 4 = Very Much). It’s also the case with academic advising (6a), personal counseling (6c), and career counseling (6b). Perhaps not surprisingly, the quality of a school’s advising and support functions matters a great deal to students.

Law School Curriculum. A final set of factors pertain to the nature of the curriculum. Students who most strongly believed they had acquired a broad legal education (10a) along with job or work-related knowledge (10b), and were taught to think critically and analytically (10b), were those who were most likely to give their law school an overall rating of “Excellent.”

What Students Want

With this short analysis, we see the value in leveraging the student perspective to focus the efforts of law school decision-makers. Students want to attend a school where relationships with other students, faculty and staff are both possible and enjoyable. For Deans, this might mean giving more weight to social functions and community-building activities than they have in the past. Students also want a sense their school is supportive, and working toward their success by providing resources to aid in both academic and personal decisions. They find greatest value when the law school curriculum equips them with skills they will need in practice. At the end of the day, “the ask” seems reasonable on its face.

___

[1] The model is a linear mixed effects regression that accounts for law school class year, survey year, and unique law school effects. More sophisticated models are certainly possible (e.g., an ordinal response model), yet in my exploration I’ve found that the conclusions shared here end up the same regardless.

Guest Post: Towards Data-Driven “Deaning”

Camille A. Nelson

Camille A. Nelson

Dean and Professor of Law

American University Washington College of Law

Surprisingly, there are few opportunities as a dean to ascertain student engagement, insights, and concerns in a manner that is comparative, data-driven, and longitudinal. LSSSE presents an opportunity to intentionally harness student-derived and student-driven data in service of the aspirations of one’s law school community, and to ensure a continuous drive for excellence in a marketplace for legal education that is relentlessly competitive.

As we are often simultaneously seeking to improve metrics, especially those reported to outside entities, while ensuring the maintenance and embrace of core values in service of a shared vision, such data and information is extremely helpful. While it is not easy to move all of the needles at once, the LSSSE survey provides a good deal of information from our students as we try to improve our schools in ways that help us better serve and support our students and alumni. Having such student-centric data from our students, combined with the information on how similarly situated schools are faring along comparable trajectories is important to our ability to recognize challenges and opportunities, and to be more diagnostic in our problem solving towards informed solutions.

As the students are the heart of any great law school, it is interesting, and unfortunate, that their views are seldom collected in durable ways that provide data over time for enterprise improvement. If we take “customer service” seriously, LSSSE appears to be one of the few, if not the only, mechanism through which to glean the holistic well-being and effective functionality of the law school as a student focused enterprise over time. For instance, despite the profound impact of the US News and World Report (USNWR) on legal education, there are no input variables that are student generated in the USNWR law school rankings from which to ascertain insight into the student experience, both specifically and comparatively.

Given the dearth of student generated data available to law school administrators and faculty, LSSSE is a helpful mechanism through which to learn, analytically, as opposed to anecdotally, about the student experience and organizational pinch-points. Deans need to learn of areas in need of trouble-shooting, especially areas that might encumber student success and well-being, or which impede the creation and maintenance of durable institutional good-will. So while I recognize that no tool is perfect, LSSSE data proves valuable in providing deans with the ability to study and assess, in protensive ways, areas that must be of importance to law schools, and legal education more generally.[1]

Some may bristle at the notion of customer service in an academic setting as inappropriately consumerist, perhaps fawning and misguided. However, for many of our students, and often their families, their monetary investment in graduate and professional schools, especially given rising tuition,[2] not surprisingly, nor unreasonably, enhances expectations for such a student facing and customer-driven focus. I empathize with the impetus for assurances along the lines of customer service -- these are often fueled by increased debt loads and what some are calling a national student debt crisis.[3]

With an average annual tuition rate of $27,160 for public law schools and $47,754 for private law schools,[4] we should expect that our students want what some may view as more from us, but which may reasonably be interpreted as value for their dollar, and for their debt. For such outlays of money and the assumption of debt, would we too not do the same in every other space of personal investment and expenditure? Such expectations are especially the case in areas that bode well for student preparation for their professional opportunities, be that from wellness and counselling, to legal research, writing and the search for employment, skills that all intersect with and amplify doctrinal and substantive acumen.

In striving to be more of a data-driven dean, LSSSE can help. I look to LSSSE to help me/us improve both our appreciation of student feedback, and also to provide a basis upon which we assess our adherence to, and support of, core values we hold dear, starting with the embrace and uplift of our students.

[1] LSSSE data supports the opportunity to study various aspects of the law school experience, including how students utilize law school services, how they study, and what their employment goals are, and how it changes over time. LSSSE, http://lssse.indiana.edu/

[2] According to data compiled by Law School Transparency, average in-state tuition for public law schools in 1985 was $2,006, while average tuition for private schools was $7,526; by 2018, average tuition had risen to $27,160 and $47,754 respectively. Law School Costs, https://data.lawschooltransparency.com/costs/tuition/.

[3] Sandy Baum and Patricia Steele, Graduate and Professional School Debt: How Much Students Borrow (January 4, 2018). AccessLex Institute Research Paper No. 18-02, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3103250 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3103250; Kristin Blagg, Underwater on Student Debt: Understanding Consumer Credit and Student Loan Default (August 2018), https://www.urban.org/research/publication/underwater-student-debt/view/full_report; National Center for Education Statistics, The Condition of Education 2018 - Trends in Student Loan Debt for Graduate School Completers, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_tub.asp; Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Research & Statistics Group, Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit, Q1 2019 (May 2019), https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/interactives/householdcredit/data/pdf/HHDC_2019Q1.pdf; Josh Mitchell, The Long Road to the Student Debt Crisis, Wall Street Journal, June 7, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-long-road-to-the-student-debt-crisis-11559923730.

Robert Farrington, The 2020 Presidential Candidates’ Proposals for Student Loan Debt, Forbes (April 24, 2019), https://www.forbes.com/sites/robertfarrington/2019/04/24/the-2020-presidential-candidates-proposals-for-student-loan-debt/#394c0a20520e; Jacob Pramuk, Elizabeth Warren and 2020 Democrats Want to Erase Student Loan Debt – Here’s How It Could Affect the Economy, CNBC (April 23, 2019), https://www.cnbc.com/2019/04/23/elizabeth-warren-and-2020-election-democrats-propose-student-loan-relief.html Also refer to increasing conversation amongst presidential candidates about same.

[4] Law School Costs, Law School Transparency (2018 data, most recent available) https://data.lawschooltransparency.com/costs/tuition/.

Mega даркнет площадка, Mega ссылка, Мега даркнет сайт Мега даркнет площадка

Guest Post: A Glimpse Beyond the Numbers

Louis M. Rocconi, Ph.D.

Louis M. Rocconi, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor, Educational Psychology and Counseling

The University of Tennessee, Knoxville

As a former LSSSE research analyst (2011-2016), I am excited to write a guest blog post for a project that means so much to me. In this blog post, I will discuss a recently published article in which my colleagues and I used LSSSE data to examine diverse interactions in law school. The full article is available in the Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. [1]

A concerted effort has been devoted to diversifying law schools. However, the focus has been almost exclusively on increasing the structural diversity of the student body (i.e., having representative numbers of a diverse population) rather than increasing the frequency and quality of interactions among students from diverse backgrounds. Research shows that meaningful interactions among students from diverse backgrounds foster many educational and psychological benefits such as reductions in prejudice, appreciation for others’ perspectives, improved critical thinking and self-confidence, greater connection to the institution, greater civic engagement, and enhancement of leadership skills. [2] Understanding how the student experience may foster diverse interactions in legal education will help law schools meet the needs of an increasingly diverse student population and society.

The concept of student engagement provides a useful

framework to explore how students’ activities and perceptions shape students’

contact with diverse others. Using data from the 2014 and 2015 administration

of LSSSE, we set out to investigate the types of activities and experiences in

law school that relate with more frequent diverse interactions. Diverse

interactions were operationalized using three items on LSSSE that asked

students how often they:

(1) had serious conversations with students of a

different race or ethnicity;

(2) had serious conversations with students who are

different from them in terms of their religious beliefs, political opinion, or

personal values; and

(3) included diverse perspectives (different races,

religions, sexual orientations, genders, political beliefs, etc.) in class

discussions or writing assignments.

We examined a number of student characteristics (e.g.,

gender, race-ethnicity, age, enrollment status), activities in law school

(e.g., interaction with faculty, higher-order learning, internship, pro bono

work, law journal, moot court, student organization), perceptions of the law

school environment and relationships with other students, as well as

characteristics of the law school (e.g., structural diversity, selectivity, public/private,

enrollment size).

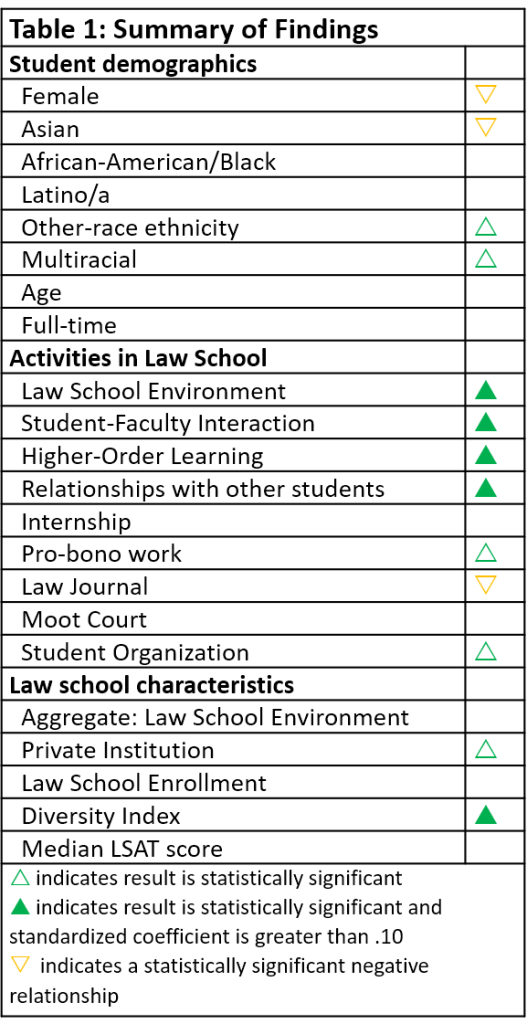

Our findings (Table 1) were encouraging for law schools. Increased diverse interactions were not only related to structural diversity but to programmatic factors that law schools can influence such as creating a supportive law school environment or encouraging student-faculty interactions. Bringing about diverse interactions requires intentional and well-designed effort on the part of the institution. Fostering these various opportunities is one way in which law schools can encourage diverse interactions.

One of the strongest relationships involves

student-faculty interactions. Students who reported more frequent interactions

with faculty also reported greater diverse interactions. Law schools can exert

some influence over certain aspects of student-faculty interaction by implementing

policies that encourage student and faculty involvement both in and out of the

classroom (e.g., mentoring programs). Our findings also illustrate that diverse

interactions were related with students’ perceptions of a supportive law school

environment. Faculty and administrators can assist in creating a supportive

environment by providing students the academic and personal support they need

to be successful. We also found that creating opportunities for students to

interact with faculty and peers in collaborative ways, particularly pro bono

service and through student organizations, were related with increased diverse

interactions.

On the other hand, we found a negative relationship between participating in the law journal and diverse interactions. The lack of diversity among law journal staff could be one reason for this finding in addition to the competitive and insulated nature of law journals. This notion is consistent with the idea that competitive environments can discourage intergroup contact and minimize the benefits of diverse interactions.[3]

More research is needed to better understand the

particular ways in which interactions among diverse groups operate in law

school. Are law students who interact more frequently with a diverse set of

peers better able to apply what they have learned in class? Are these students

better prepared to work with a diverse set of clientele? Understanding diverse

interactions will help law schools meet the needs of an increasingly diverse

student body and better prepare students to meet the needs of the diverse array

of clients these future lawyers will represent.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge my co-authors without whom this research would not have been possible: Aaron Taylor, Heather Haeger, John Zilvinskis, and Chad Christensen.

_______

[1] Rocconi, L.M., Taylor, A.N., Haeger, H., Zilvinskis, J.D., & Christensen, C.R. (2019). Beyond the numbers: An examination of diverse interaction in law school. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 12(1), 27-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000080

[2] see for example: Bowman, N. A. (2011). Promoting participation in a diverse democracy: A meta-analysis of college diversity experiences and civic engagement. Review of Educational Research, 81, 29–68. Nelson Laird, T. F. (2005). College students’ experiences with diversity and their effects on academic self-confidence, social agency, and disposition toward critical thinking. Research in Higher Education, 46, 365– 387. Parker, E. T., III, & Pascarella, E. T. (2013). Effects of diversity experiences on socially responsible leadership over four years of college. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 6, 219–230. Pascarella, E. T., Martin, G. L., Hanson, J. M., Trolian, T. L., Gillig, B., & Blaich, C. (2014). Effects of diversity experiences on critical thinking skills over 4 years of college. Journal of College Student Development,55, 86–92.

[3] Pettigrew, T. F., Christ, O., Wagner, U., & Stellmacher, J. (2007). Direct and indirect intergroup contact effects on prejudice: A normative interpretation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 31, 411–425. Pettigrew, T. F., Tropp, L. R., Wagner, U., & Christ, O. (2011). Recent advances in intergroup contact theory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35, 271–280.

Guest Post: Paying for Law School and the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program

Guest Post by CJ Ryan, J.D., Ph.D.

Guest Post by CJ Ryan, J.D., Ph.D.

Associate Professor of Law, Roger Williams University School of Law

Affiliated Scholar - American Bar Foundation

Legal education in 2019 is a costly proposition for most law students. The average cost of tuition and fees at private law schools was $49,095 and $40,725 at public law schools, for out-of-state students, in the 2018-2019 academic year, to say nothing of living expenses and other costs that students pay out of pocket.[1] As a result, many law school graduates carry significant student loan debt upon completing their studies. In fact, the average amount borrowed by law school graduates totaled $115,481 for the graduating class of 2018.[2]

When discussing student loan debt, it is easy to fixate on the aggregate impact of the burdens this debt places on tax payers, the economy, and borrowers alike, such as the depressive effects that law school loan debt has on homeownership and entrepreneurship.[3] Yet, a discussion of which graduates are saddled with the largest student loans is often absent from conversations about student debt.

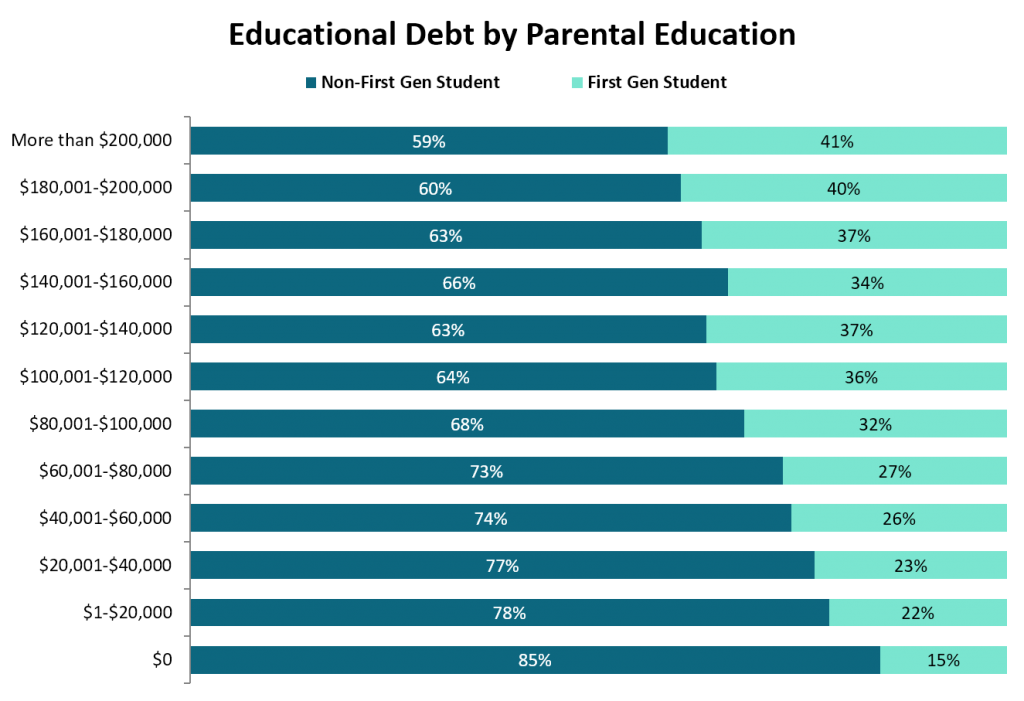

The results of the 2018 Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) reveal that students from the lowest socio-economic backgrounds, as proxied by parental education, expect the greatest debt loads upon graduating from law school. In fact, among students expecting to owe between $180,000 and $200,000, 40% of these students have parents whose highest level of educational attainment was less than a baccalaureate degree, and the proportion jumps to 42% of students who expect to owe more than $200,000 in student loans from attending law school. Thus, unsurprisingly, students from the lowest socio-economic backgrounds borrow the most to finance their legal education and, perhaps as a result, are on the hook for the largest debt sums.

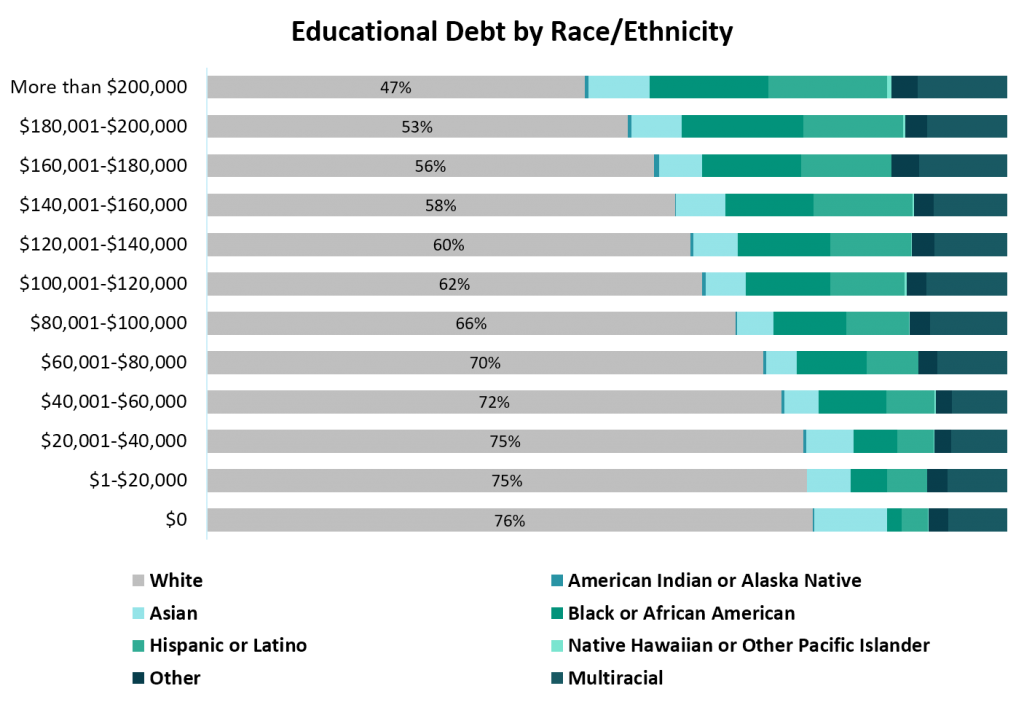

Furthermore, students from racial minority groups account for the largest expected law school debt loads. Of the students surveyed by LSSSE who expected to owe more than $200,000 in law school loans following their graduation, 53% identified with a racial group other than White. Thus, the disparate impact of the highest law school loans is greatest among racial minorities.

Fortunately, income-based repayment options for student loans make paying back significant debt loads for law school graduates more manageable. One repayment option, the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program, even forgives borrowers a portion of their student loan debt, subject to paying into the program for 10 years of full-time employment with a government organization, or a qualifying public service or tax-exempt organization under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code.[4] However, the future of the PSLF remains uncertain, as the Department of Education, as well as President Trump, have announced plans to eliminate PSLF.[5]

In the fall of 2017, I administered the Law School Choice Survey at four law schools: a private elite law school; a public flagship law school; a public regional law school; and a private new law school.[6] The response rate within this sample of law students was quite robust—45%, 34%, 40% and 43%, respectively—and respondents to the survey were representative of their law school’s entire population on the basis of race and gender, within two%, in each category.[7] The survey queried current law students about their career aspirations and whether they planned to take advantage of the PSLF program to repay their student loans. Responses from students at the public flagship law school indicated that 16% of White students planned to enroll in or were already enrolled in PSLF, but 20% of the African-American students and half of the Hispanic/Latino students planned to enroll in or were already enrolled in PSLF. At the public regional law school, nearly 29% of White students indicated that they planned to enroll in or had already paid into PSLF, but half of the Hispanic/Latino students and 70% of African-American students planned to enroll in or had already paid into PSLF. At the private new law school, 33% of African-American students and over 35% of White students surveyed indicated that they plan to avail themselves of PSLF.[8] Furthermore, nearly 77% of students at the public flagship law school, and over 55% of students at the public regional and private new law schools, with expected law school loan debt exceeding $100K, indicated that they plan to enroll or were enrolled in PSLF. These results demonstrate that a significant proportion of racial minority students, as well as their White counterparts, and students with the greatest expected debt loads view the PSLF as their primary recourse for repaying their law school loans.

Likewise, 40% of the students whose parents earned a combined income of less than $50,000 annually plan to enroll or were already enrolled in the PSLF program at the public flagship law school. At the public regional law school, over 21% of students whose parents earned less than $50,000—but more than 44% of the students who parents earned less than $60,000 annually—are counting on the PSLF program. And over 58% of the students whose parents earned less than $50,000 annually at the private new law school indicated that they plan to use or are enrolled in the PSLF to repay their student loans.

Additionally, over 35% of students who planned to enter a career in traditional public interest sectors indicated that they planned to or had already enrolled in PSLF.[9] More than 54% of students who sought a career in a public interest sector at the public regional law school indicated that PSLF was a part of their loan repayment plans. And over 30% of students at the new private law school who plan to enter a career in the public interest sector reported that they plan to repay using PSLF.

Taken together, these results suggest that that the students who most need relief for their substantial law school loans—students from lower socio-economic backgrounds, students from diverse racial backgrounds, students considering careers in public interest law, and students carrying the highest debt loads, most of whom are the same students across these four categories—are the students most likely to enroll in the PSLF program. Thus, despite the administrative challenges associated with the PSLF program,[10] it has succeeded in attracting law graduates to careers in the public interests, and particularly racial minority law graduates.[11] As such, it presents the most viable path to ensuring diversity in the legal profession, in terms of socio-economic status and race, but it also has substantial implications for ensuring access to justice. PSLF provides an important pathway for lawyers willing to serve in public interest roles, often at dramatically lower salaries than their peers who pursue careers in the private sector, to repay their loans, while helping to address the unmet demand for legal services for those with the greatest need in our society.[12] To eliminate the PSLF program, and these important goals that it accomplishes, would be a mistake.

____

[1] See, e.g., Ilana Kowarski, See the Price, Payoff of Law School before Enrolling, U.S. News & World Report, March 12, 2019, https://www.usnews.com/education/best-graduate-schools/top-law-schools/articles/law-school-cost-starting-salary.

[2] Law School Costs, Law School Transparency, https://data.lawschooltransparency.com/costs/debt/.

[3] Alvaro Mezza, Daniel Ringo, and Kamila Sommer, Can Student Loan Debt Explain Low Homeownership Rates for Young Adults?, Federal Reserve Board, January 2019, https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/consumer-community-context-201901.pdf; see also, Vadim Revzin and Segei Revzin, Student Debt Is Stopping U.S. Millenials from Becoming Entrepreneurs, Harvard Business Review, April 26, 2019, https://hbr.org/2019/04/student-debt-is-stopping-u-s-millennials-from-becoming-entrepreneurs.

[4] The Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program, Federal Student Aid, https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/repay-loans/forgiveness-cancellation/public-service#qualifying-employment.

[5] Zack Friedman, Trump Proposes to End Student Loan Forgiveness Program, Forbes, March 12, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/zackfriedman/2019/03/12/trump-proposes-to-end-student-loan-forgiveness-program/#3cb3d8e5415e.

[6] See Christopher J. Ryan, Jr., Analyzing Law School Choice, 2020 Ill. L. Rev. ___ (forthcoming 2020), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3309815. As a condition of their participation in the survey, the law schools at which the survey was administered asked to remain anonymous and only be identified by descriptive terms. The administration at the private elite law school would not permit me to ask whether students at the law school were planning to enroll or had already paid into the PSLF program; however, all other survey questions were common between law schools.

[7] See id.

[8] Curiously, no Hispanic/Latino students surveyed at the new private law school indicated that PSLF was included in their loan repayment plans but both of the Asian-American law students surveyed indicated that they planned to enroll or were enrolled in the PSLF program. However, it should be noted that the private new law school is not terribly diverse in terms of race.

[9] These law career sectors included: children’s law/ juvenile justice; civil liberties and civil rights; criminal law; education law; employment/labor law; family law; general legal services; government law; housing law; immigration law; and public interest law.

[10] Zack Friedman, 99.5% of People Are Rejected for Student Loan Forgiveness Program, Forbes, January 3, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/zackfriedman/2019/01/03/student-loan-forgiveness-data/#14c9cb3e68d0.

[11] See, e.g., Public Service Loan Forgiveness Data, Dept. of Educ., March 2019, available at https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/about/data-center/student/loan-forgiveness/pslf-data.

[12] For example, it is estimated that legal aid lawyers “are estimated to provide just 1 percent of the total legal needs in the United States each year[.]” Three Ways to Meet the “Staggering” Amount to Unmet Legal Needs, Am. Bar Ass’n J., June 26, 2018, https://www.americanbar.org/news/abanews/publications/youraba/2018/july-2018/3-ways-to-meet-the-staggering-amount-of-unmet-legal-needs-/.

Guest Post: Using LSSSE Data to Determine Which Law School Activities Impact Student-Reported Gains in Writing Skills

Guest Post by Kirsten Winek, J.D., Ph.D.

Guest Post by Kirsten Winek, J.D., Ph.D.

Manager, Law School Analytics and Reporting

American Bar Association Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar

Successfully completing a dissertation is never easy. However, perseverance, coffee, and robust data can make the process manageable. LSSSE was invaluable to my dissertation research, since it collects information on the activities of law students nationwide as well as their evaluation of how the law school experience contributed to their gains in writing skills.

Having previously worked in law school career services, I was familiar with criticisms that law students and graduates lacked the writing skills needed for law practice. A review of the legal education literature turned up studies that delved into this issue and affirmed this was a problem. As such, I decided to focus my dissertation research on determining which law school activities impacted law students’ self-reported gains in writing skills since this information could help law schools prepare their students for the writing required in law practice and on the bar exam. My data came from the 2018 LSSSE administration, which surveyed law students about numerous law school activities and asked them to evaluate the extent their law school experience contributed to their writing skills gains. I limited my sample to all full-time, third-year LSSSE takers as they would have had the opportunity to take upper-level writing courses, legal clinics, and writing-centric extracurricular activities such as Law Review and Moot Court.

To frame my research, I used Alexander Astin’s Involvement Theory. This theory posits that the more students involve themselves in their higher education experience, the more they learn and grow from that experience. Thus, students who participate more in their law school experience may realize skills gains from that experience. To guide my data analysis, I used Alexander Astin’s I-E-O model (Inputs-Environment-Outcomes). Inputs are the attributes students bring with them to higher education, environment is all the pieces of the higher education experience, and outcomes are the skills and attributes students have at the end of the higher education experience.

Although Astin developed the aforementioned frameworks using undergraduate students, both can be applied to law students and work quite well with LSSSE data. LSSSE is based on student engagement theory, which is very similar to Astin’s Involvement Theory. LSSSE gathers the data needed for the inputs, such as LSAT scores, undergraduate GPA, race/ethnicity, gender identity, age, and parental education. To encompass the law school environment, LSSSE asks students dozens of questions about their courses and class preparation, co-curricular activities, interactions with peers and faculty, and satisfaction with various aspects of law school. Finally, for the outcome of this study, LSSSE provided information on law students’ self-reported writing gains via the question asking students to evaluate the contributions their law school experience made to their writing skills.

After running the LSSSE data through a stepwise multiple regression analysis, several statistically significant predictors of student self-reported writing gains emerged. I will focus on the four strongest predictors here.

Interestingly, the four strongest predictors of law student self-reported gains in writing skills were actually self-reported gains in other skills. The extent to which students’ law school experience contributed to their skills in 1) speaking clearly and effectively, 2) thinking critically and analytically, 3) developing legal research skills, and 4) acquiring job or work-related knowledge and skills, respectively, all positively impacted student self-reported writing gains.

What are the implications of these findings for law schools? The fact that gains in three different skills (speaking, thinking, and researching) each had a positive relationship to self-reported writing gains revealed that writing skills are not learned in a vacuum – they are developed together with other skills. Critical and analytical thinking as well as legal research are essential parts of legal writing, and preparing for an oral argument or presenting on one’s written work may help in the writing process, too. Therefore, when possible, writing should be taught or practiced in conjunction with speaking, critical and analytical thinking, and legal research since these skills each had a positive impact on student self-reported gains in writing. Introductory legal writing courses usually combine all these skills, but this approach may not be practical in upper-level courses that do not have writing as a focal point. However, faculty teaching a seminar course that includes a paper or supervising student law review articles could require students to orally present on their work so they involve all three skills, as legal research and critical and analytical thinking are already key parts of these writing assignments.

Additionally, the positive relationship between student self-reported gains in work or job-related skills and student self-reported gains in writing is unsurprising given the prominent role writing plays in legal practice. Law schools should stress to students how important good writing is for legal practice, as well as for success on the bar exam, and ensure they learn and practice writing skills throughout their time in law school.

These selected findings from my dissertation research provide a look at the valuable insights LSSSE can provide to researchers and legal education. These implications should encourage law schools to maintain or increase the work they may already do in helping their students learn or practice legal writing skills.

Guest Post: Be True to Your School: But True to Your Law School?

Guest Post by Stephen Daniels

Senior Research Professor

American Bar Foundation

Be True to Your School was a popular song of an earlier time extolling staunch loyalty to one’s alma mater. But staunch loyalty to your law school these days in light of high tuition, high student debt, concerns about inadequate preparation, and mediocre job prospects? Two recent reports drawing from retrospective surveys of graduates done by Gallup – one as a part of the Gallup-Purdue Index and the other done in conjunction with AccessLex Institute – suggest that many see little value in their legal education given the cost. Those choosing to attend law school make a substantial investment with the expectation of a substantial return. Is there value in the proposition? Is there cause to be true to your school?

I do research on legal education from an institutional perspective and the question about value animates much of my current work involving law students.[1] Students – or more precisely, their tuition dollars – are indispensible for legal education. The LSSSE survey data allow me to explore students’ views over time in search of an answer for that question.

The LSSSE data are important because they provide not just information about students, but information from students. Simply put, the surveys give voice. The data are especially unique because they are longitudinal, the surveys asking students a host of questions over time using the same wording – the gold standard for examining change, or the lack thereof, in views, attitudes, or assessments.

Although the data do not cover all schools, and LSSSE does not claim to have a representative sample of all schools or students, the range of participating schools is wide. The number of respondents in any given year or set of years is large. The 2016 survey, for example, had over 18,000 respondents from 72 schools; in 2010 the figures were just under 23,500 from 73 schools.

My current project using the LSSSE data – Be True to Your School: But True to Your Law School? – explores patterns and changes in law student assessments of their schools. The question about being true to one’s school provides a framework, a heuristic for exploring a range of factors important to students given the investment they are making. In that old song, what made you true to your school was its winning football team. What makes a law student true to their school is the school’s success in meeting their expectations – enough, to paraphrase a LSSSE survey question, that the student would attend that school again if given the choice.

The data I utilize cover the years 2005 through 2016. They include respondents from 38 schools participating in the LSSSE surveys at least three times between 2005 and 2010, and at least three times between 2011 and 2016 (allowing for comparisons before and after the 2010 enrollment peak and subsequent decline). Focusing on those 38 schools—which were not identified, just as the students themselves remain anonymous—provides a reasonable degree of continuity. Not all respondents from those schools are included, just those at the end of their law school experience (usually 3Ls and occasional part-time students who take a fourth year (4Ls) to complete their studies). Structured this way the data set consists of 33,661 survey respondents.

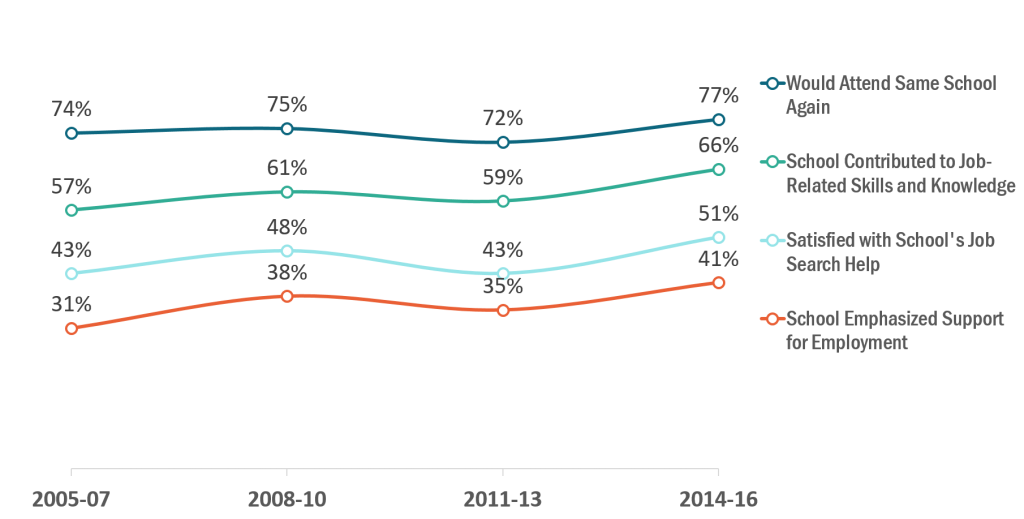

Are 3/4Ls at least reasonably true to their schools? In apparent contrast to the Gallup surveys, preliminary analyses suggest yes – at least in general. Most respondents said they (probably or definitely) would attend the same school again.

Affirmative Answers to Select LSSSE Questions by Time Period

(3/4L respondents in 38 schools)

Additionally, the percentages reflect some stability over time with regard to attending the same school again. The 2011-13 dip reflects the cohort graduating as the post-2010 enrollment declines began, with the next cohort having a somewhat more positive view. It was the effect of a drop in affirmative responses from private school students (from 75% in 2008-10, to 69% in 2011-13). There was no similar decline for public schools (81% in 2011-13, 85% in 2014-16 to 80%). Not surprisingly, the most important factor for an affirmative answer about attending the same school again was a student’s evaluation of their overall law school experience.[2]

While attending the same school is a summary question close to the Gallup surveys’ interest in value, other LSSSE questions probe the idea of value more deeply and are more revealing of the complexities of students’ views. One question asks the extent to which the law school contributed to acquiring work-relevant knowledge and skills. The graph shows that a majority responded affirmatively about their school’s contribution, with an upward trend except for another 2011-13 dip (again, private schools).

This particular contribution was especially important for those respondents saying they would attend their school again, as 70% also answered affirmatively about their school’s contribution to work-relevant knowledge and skills. For those not so interested in attending their school again, only 37% thought their school made that contribution.

Another two questions ask about crucial employment-related matters. One question asked about satisfaction with the school’s help in finding a job for those using it (86% did use that help). As that column shows, most respondents were not enthusiastic in their assessments (with the 2011-13 dip). Students who would not attend their school again were even less enthusiastic about the help provided -- the percentage of them offering a positive assessment ranged only from 20% in 2005-07 to 25% in 2008-10.

The other employment-related question asked about the degree of a school’s support for the student’s own employment search. Most respondents did not find their schools particularly helpful in this regard (with the 2011-13 dip). Those who would not attend their school again were even more negative in their assessments on support. Their assessments ranged from only 11% in 2005-07 to 18% in 2014-16. Even a majority (57%) of those who would attend their school again had a negative assessment of their school on this matter.[3]

The responses to these three questions reflect longer-term areas for concern and may provide a hint as to why respondents in the Gallup retrospective surveys were doubtful about the value of their investment. Again, these are preliminary findings from a project very much in progress, with much left to do. What is clear is the importance of the LSSSE data for digging systematically into the details of what students say about the value of their investment.

[1] Funded in part by a grant from AccessLex Institute.

[2] Spearman’s rho =.68, sig.=.000.

[3] Responses to the employment questions are strongly related, Spearman’s rho = .74, sig. = .000.

Guest Post: LSSSE as a Key Tool to Support the Learning Outcomes Enterprise

Guest Post by Jerry Organ

Professor of Law and Co-Director of the Holloran Center for Ethical Leadership in the Professions

University of St. Thomas School of Law (Minnesota)

In 2014, the ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar mandated that law schools adopt learning outcomes. As of March 1, 2019, over 180 law schools have published learning outcomes on their websites. The Learning Outcomes Database on the website of the Holloran Center for Ethical Leadership in the Professions -- https://www.stthomas.edu/hollorancenter/resourcesforlegaleducators/learningoutcomesdatabase/ --provides a searchable set of databases of publicly available law school learning outcomes organized under three categories -- learning outcomes associated with

- Standard 302(a) (knowledge and understanding of substantive and procedural law),

- Standard 302 (b) and (d) (legal analysis and reasoning, legal research, problem-solving, and written and oral communication in the legal context (b) along with other related professional skills (d)), and

- Standard 302 (c) and (d) (exercise of proper professional and ethical responsibilities to clients and the legal system (c) along with other related professional skills (d)).

The learning outcomes enterprise contemplates that each law school will engage in an assessment process in which it analyzes the extent to which its program of legal education is helping its law students progress on the law school’s identified learning outcomes. Having engaged in that assessment effort, the law school then should “close the loop” and figure out whether it needs to make changes in its program of legal education to improve the extent to which its students are making progress on the law school’s identified learning outcomes. This is an iterative process that should result in continual improvement over time in the extent to which the program of legal education is helping students progress on the identified learning outcomes.

Law schools may feel that there are some traditional measures that can be used to assess progress on learning outcomes associated with Standards 302(a) and 302(b), such as performance in doctrinal courses and legal research and writing, and possibly performance in experiential courses and clinics, and performance on the bar exam. A significant number of law schools, however, have identified robust professional formation learning outcomes associated with Standard 302(c) and 302(d) for which these traditional measures may not be very helpful, including self-directedness, cultural competence, commitment to pro bono, teamwork/collaboration, and integrity among others.

LSSSE can be an important tool to support the assessment efforts associated with the learning outcomes enterprise, particularly with respect to some of these “professional formation” learning outcomes.

First, within the LSSSE survey instrument itself, there are a number of questions that relate to some of the learning outcomes identified above.

With respect to cultural competence, for example, the following questions could be informative:

- How often have you had serious conversations with students of a different race or ethnicity than your own?

- How often have you had serious conversations with students who are very different from you in terms of their religious beliefs, political opinions, or personal values?

- How often have you included diverse perspectives (different races, religions, sexual orientations, genders, political beliefs, etc.) in class discussions or writing assignments?

- To what extend does your law school emphasize encouraging contact among students from different economic, social, sexual orientation, and racial or ethnic backgrounds?

- To what extent has your experience contributed to your understanding people of other racial and ethnic backgrounds?

While these questions do not speak directly to a student’s level of cultural competence, they can inform whether various interventions or curricular or co-curricular innovations a school has implemented have resulted in more interactions among students of diverse backgrounds and can measure the perception of the school’s commitment to emphasizing interactions among students of diverse backgrounds.

With respect to commitment to pro bono, there are four questions that could be used to assess the extent to which engagements or interventions around pro bono have had a meaningful impact in the student experience:

- How often have you participated in a clinical or pro bono project as part of a course or for academic credit?

- Have you done pro bono work or public service?

- How many hours do you spend in a week on legal pro bono work not required for a class or clinical course?

- To what extent has your experience contributed to your contributing to the welfare of your community?

With respect to teamwork/collaboration, there are a handful of questions that could be instructive:

- How often have you worked with other students on projects during class?

- How often have you worked with classmates outside of class to prepare class assignments?

- To what extent has your experience contributed to your working effectively with others?

Similarly, the following questions may be instructive with respect to integrity:

- To what extent does your law school emphasize encouraging the ethical practice of the law?

- To what extent has your experience contributed to your developing a personal code of values and ethics?

- To what extent has your experience contributed to your understanding yourself?

As noted above in the discussion regarding cultural competence, many of these questions are not direct measures of one’s attitudes or capabilities. Rather they serve as indirect measures of how the students experience the law school culture and the extent to which that culture provides certain opportunities or experiences for students. For law schools trying to determine whether a given change in course requirements or instructional methodologies or co-curricular programming has had a meaningful impact, these indirect measures can be a helpful supplement to other measures, such as observations of students or reflective writing.

Second, LSSSE supports supplemental question sets or modules. This use of modules might be an even more powerful mechanism for supporting the assessment process regarding some of these professional-formation learning outcomes. The module concept generally contemplates that multiple law schools would ask a supplemental set of questions usually focused on a common theme or attribute. Thus, several law schools that each had a learning outcome associated with commitment to pro bono or teamwork/collaboration or self-directedness could come up with a bank of additional questions focused more significantly on one of those learning outcomes. This “module” could then be used at each of those law schools to get feedback that is law school specific and comparative.

The most fruitful mechanism for using either existing questions or modules is to participate in multiple iterations of the LSSSE, such as bi-annually, which allows a school to see comparisons over time on two platforms. First, one can assess the change between first-year and third-year, for example. Second, one can assess change among first-years and third-years over time. This can be an especially effective way to assess whether a change in curricular offerings or co-curricular programming has had a meaningful impact.

The simple point I want to communicate is that law schools need to be thinking about LSSSE as a real partner in the learning outcomes enterprise. In addition, law schools should be thinking about working in partnership with other law schools and LSSSE on modules that could make LSSSE an even more powerful assessment tool.