Preparing Law Students for a Multicultural World

Alongside developing analytical skills and learning about the law, law students must learn how to work effectively in a diverse, multicultural environment. Law schools have a responsibility to prepare their students by providing them with the knowledge, skills, and experiences necessary to navigate complex cultural dynamics. This can be achieved through a variety of means, including offering courses on cross-cultural communication and conflict resolution, providing opportunities for international study and internships, and fostering a diverse and inclusive campus community. By equipping law students to work effectively in a multicultural world, law schools can help to ensure their graduates are well-prepared to meet the challenges of an interconnected global society.

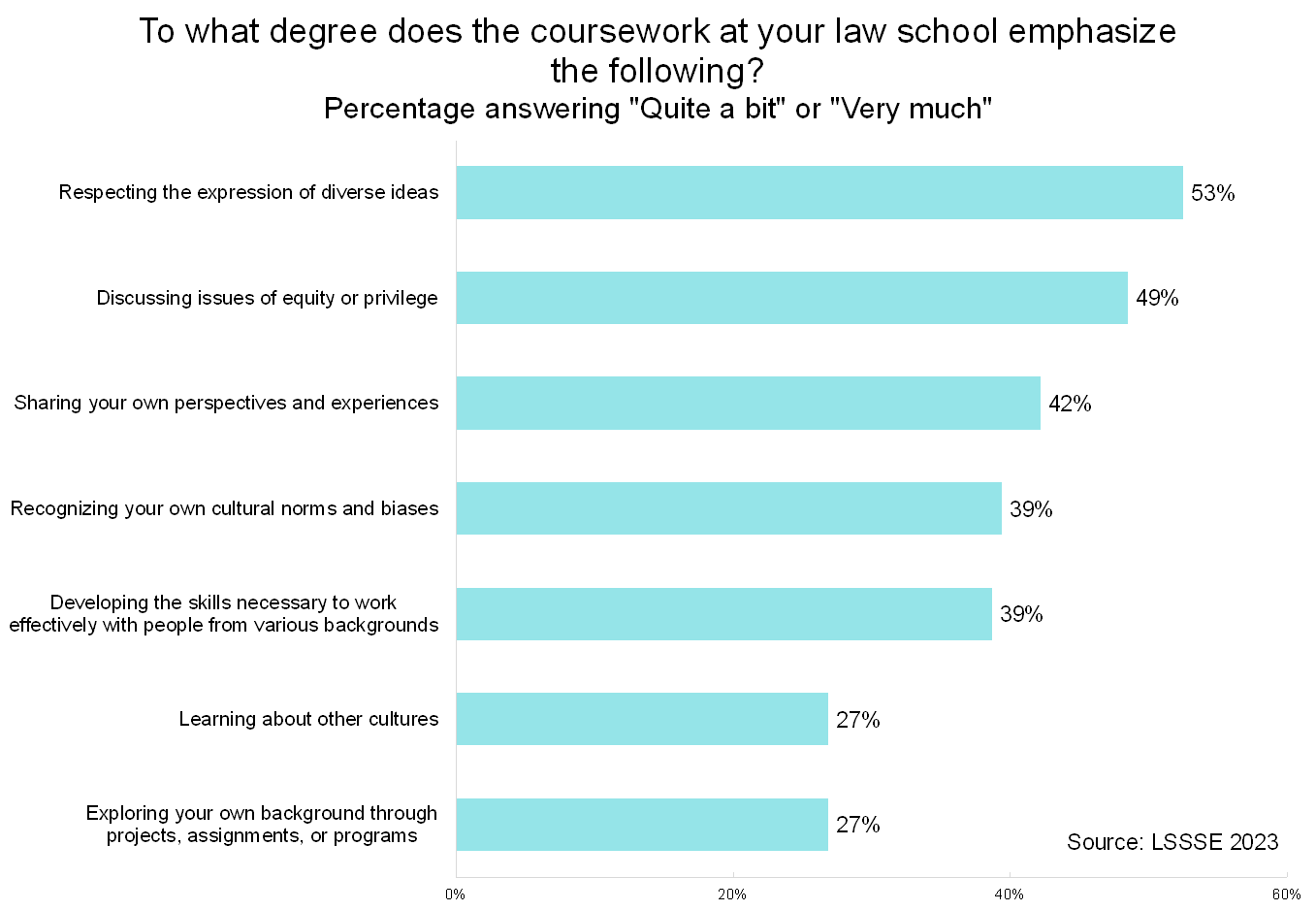

We wanted to understand the degree to which law students feel that their law school's coursework helps them learn to interact effectively and respectfully with others who are different from them. LSSSE asks students about the degree to which the coursework at their law school emphasizes various foundational principles of diversity and inclusion. In 2023, more than half of law students (53%) felt their coursework placed quite a bit or very much emphasis on respecting the expression of diverse ideas, and nearly as many (49%) experienced an emphasis on discussing issues of equity or privilege. However, only slightly more than a quarter (27%) of students felt that their law school emphasized learning about other cultures, and the same percentage felt their law school emphasized exploring students’ own backgrounds through projects, assignments, or programs

By creating a climate of academic freedom and intellectual diversity, law schools promote the values of democracy and human rights, which are essential for the rule of law and social justice. Only 14% of students said their law school placed very little emphasis on respecting the expression of diverse ideas, so clearly law schools value broader ideals around freedom of expression. However, law students also need to understand their own cultural background and how it shapes their worldview, values, and assumptions. By exploring their own identity and experiences, law students can gain insight into how they perceive themselves and others and how they relate to people who are different from them. This can help them respect and value others' contributions. Furthermore, by understanding their own cultural background, law students can also identify areas where they may need to learn more or adapt their behavior to work effectively in a multicultural context.

Courses on cultural diversity and inclusion, implicit bias, and cross-cultural communication can provide students with the knowledge and skills necessary to work effectively in a multicultural environment. Additionally, incorporating case studies and simulations that expose students to real-world scenarios can help students to develop practical skills in navigating complex cultural dynamics. By providing students with opportunities to engage in critical reflection and dialogue, law schools can help students to become more aware of their own biases and to develop strategies for mitigating their impact.

SPOTLIGHT ON: Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Law Students

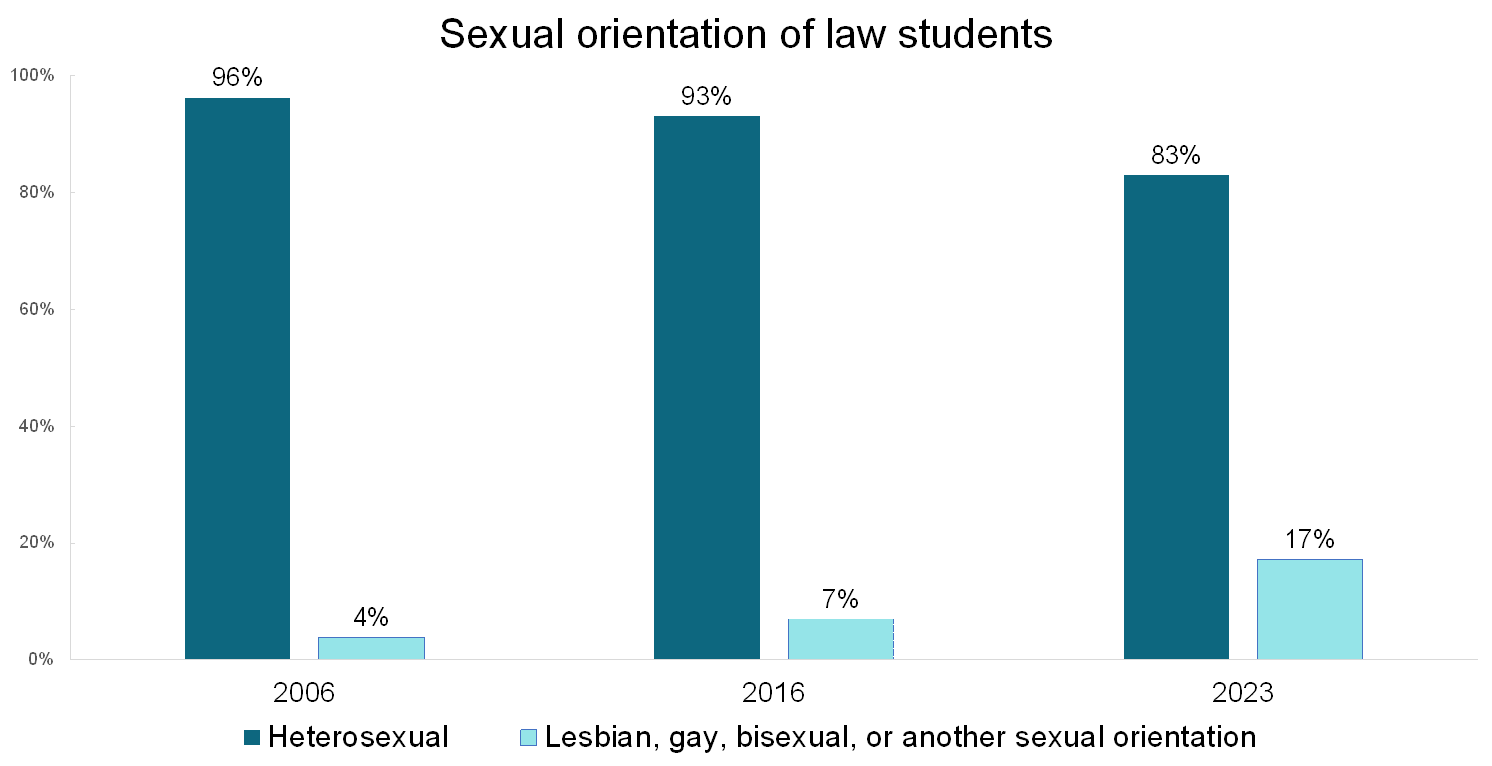

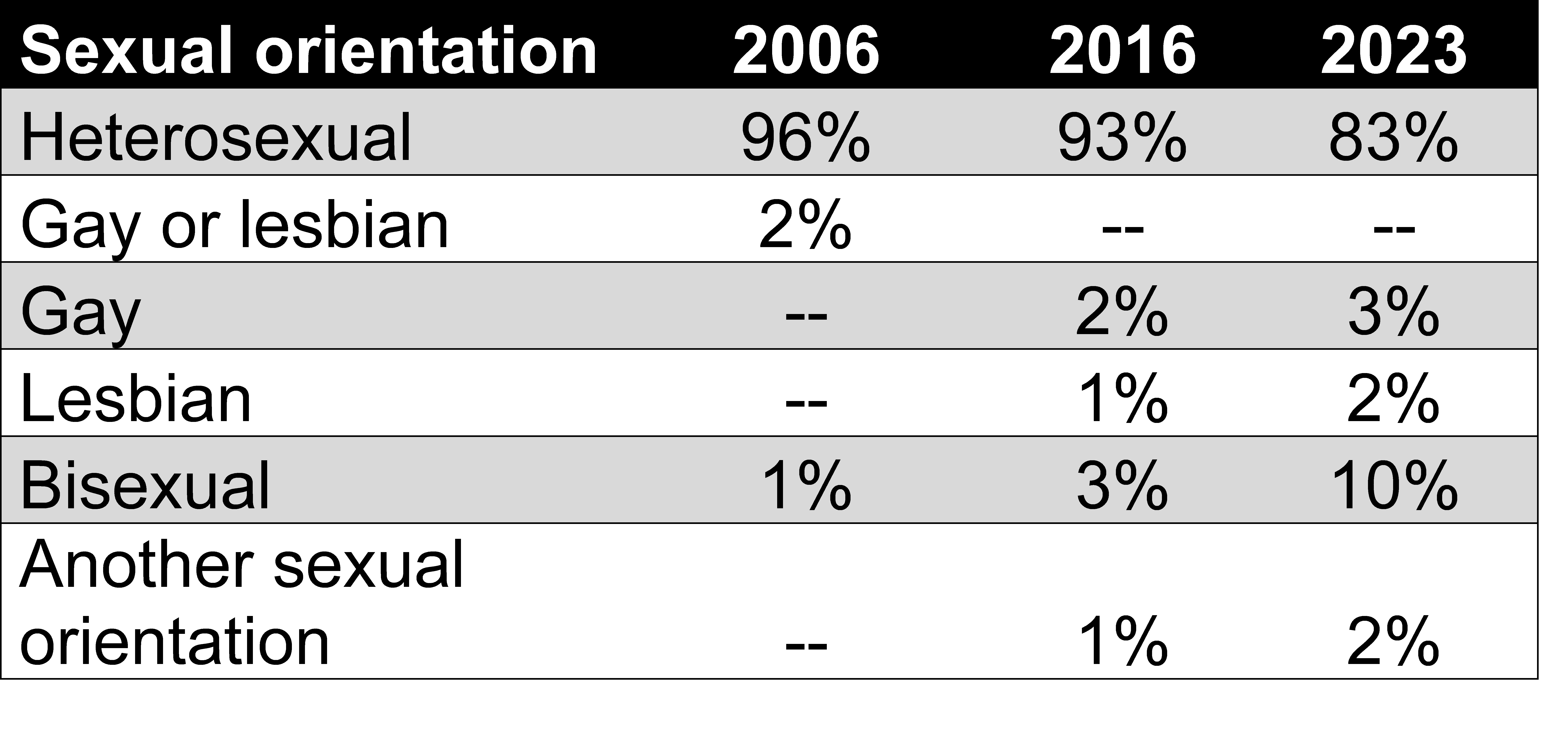

The percentage of law students who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or another non-heterosexual sexual orientation (LGB+) has grown dramatically over the last twenty years. When LSSSE first began asking about sexual orientation in 2006, 96% of law students identified as heterosexual, 2.5% were gay or lesbian, and only 1.3% were bisexual. The numbers had shifted noticeably by 2016, when the sexual orientation question was revamped slightly to be more inclusive. That year, 93% of law students were heterosexual, 2.3% were gay, 1.1% were lesbian, 2.6% were bisexual, and 0.9% were of another sexual orientation. However, by 2023, only 83% of law students identified as heterosexual. Three percent were gay, 1.7% were lesbian, 2% had another sexual orientation, and a full 10% identified as bisexual.

-- indicates response option was not available that year

-- indicates response option was not available that year

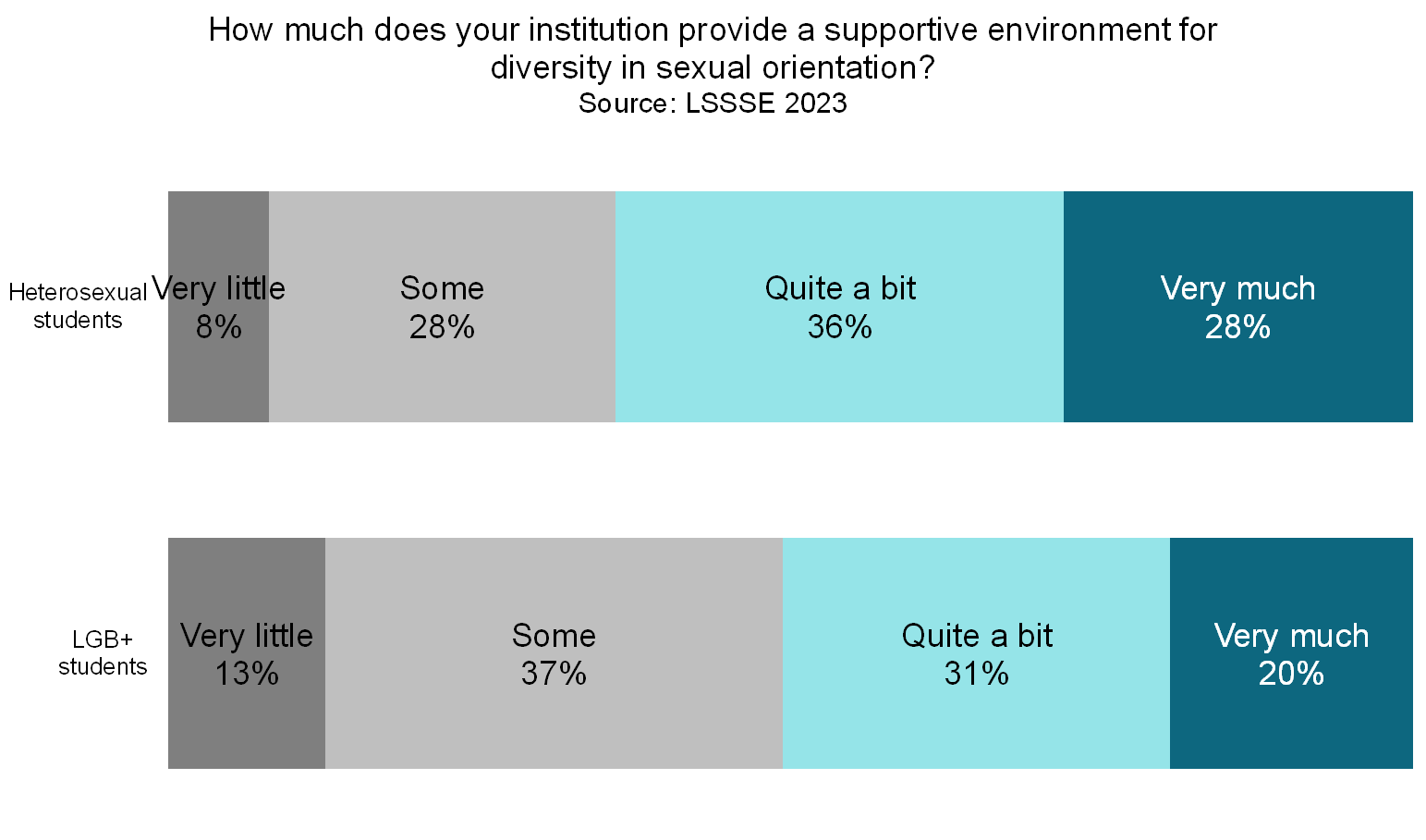

LGB+ students are somewhat less comfortable in law school relative to their heterosexual peers. For example, 72% of LGB+ students feel that they are part of the law school community compared to 77% of heterosexual students. Only half (50%) of LGB+ students believe that their law school places quite a bit or very much emphasis on ensuring that they are not stigmatized because of their identity (racial/ethnic, gender, religious, sexual orientation, etc.) compared to 61% of heterosexual students. Similarly, only about half (51%) of LGB+ students believe that their law school is a supportive environment for diversity in sexual orientation compared to just under two-thirds (64%) of heterosexual students.

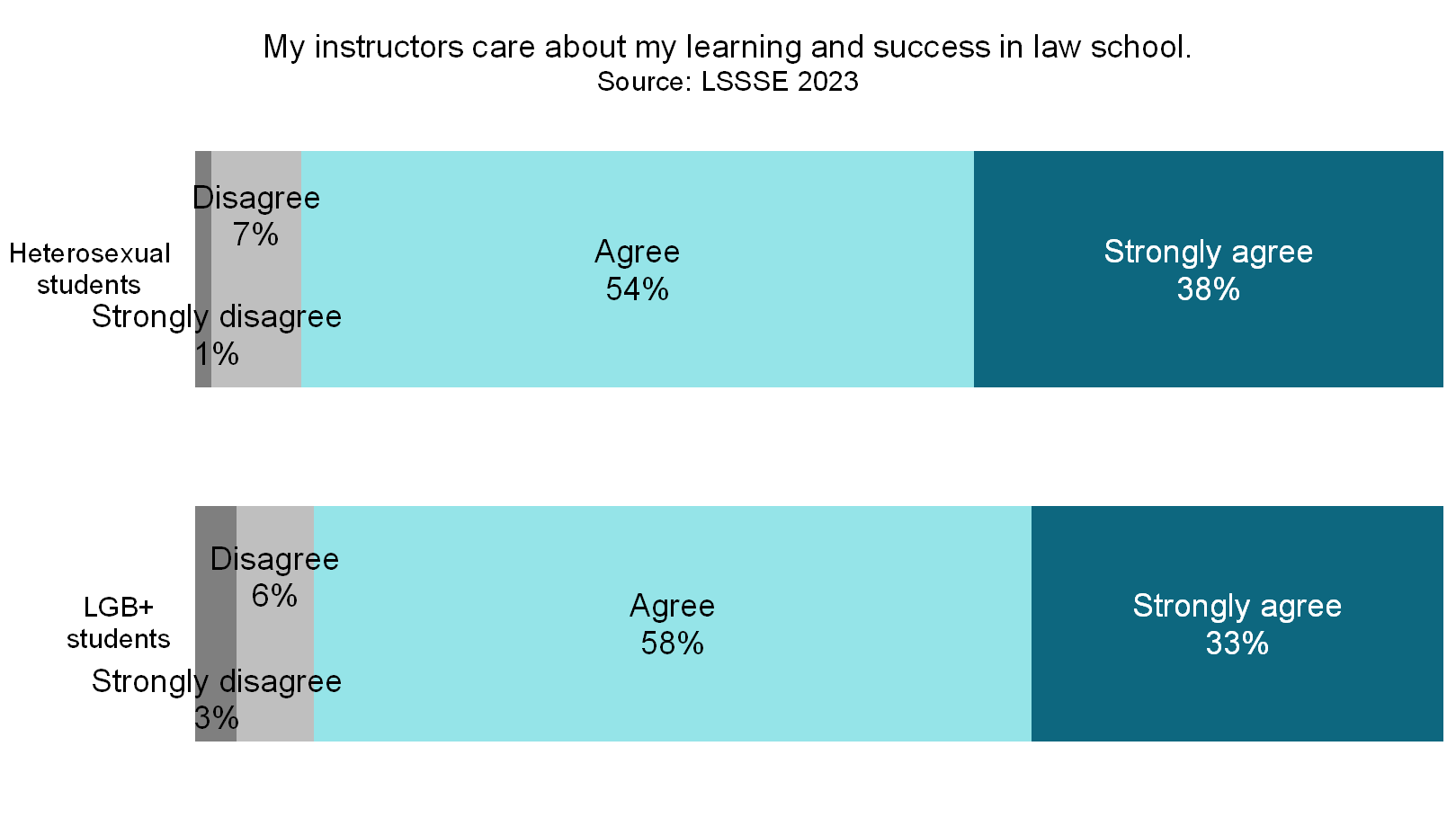

Despite the perception of a somewhat chilly climate overall, LGB+ law students are nearly equally likely as heterosexual law students to have strong relationships with law school faculty. LGB+ students rate their relationships with faculty on average 5.2 on a seven-point scale, compared to 5.3 for heterosexual students. A full 91% of LGB+ students believe their instructors care about their learning and success in law school, nearly equal to the 92% of heterosexual students who feel that way. Around four in five LGB+ and heterosexual students consider at least one instructor a mentor whom they feel comfortable asking for advice or guidance. Clearly, most students find help and support from their law school faculty, regardless of their sexual orientation.

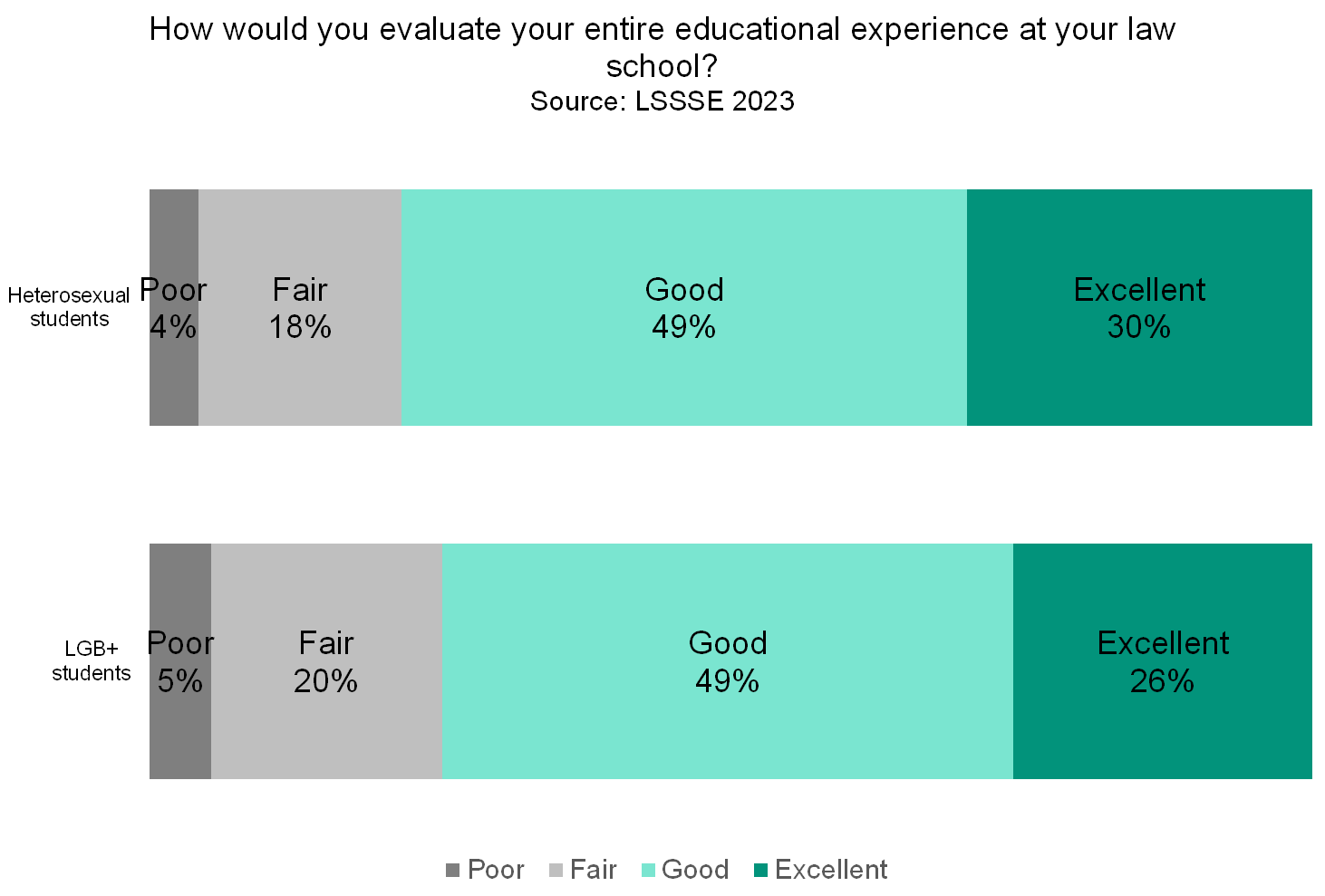

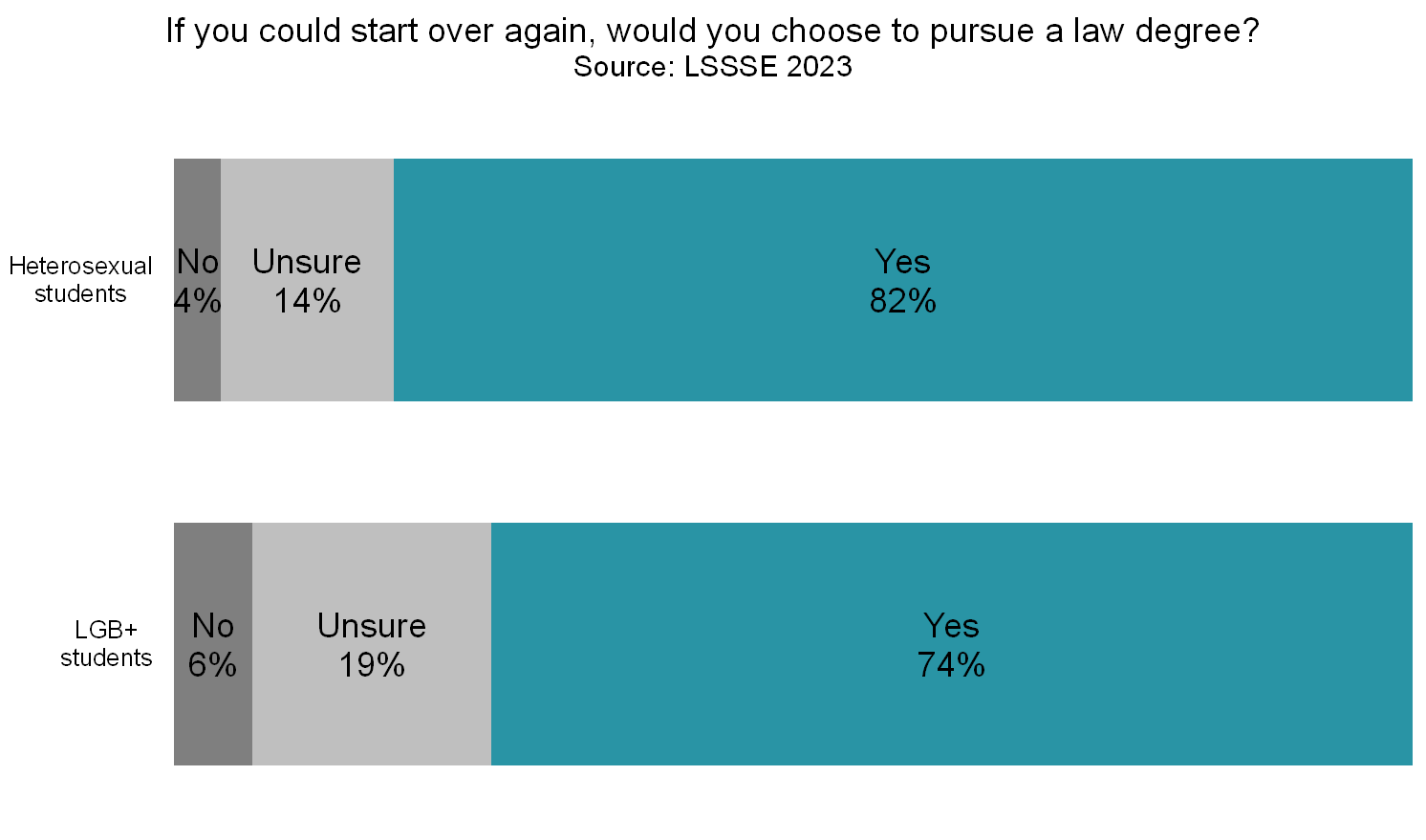

LGB+ students are somewhat less satisfied with their overall experience at law school compared to heterosexual law students. Three-quarters (75%) or LGB+ students rate their experience “good” or “excellent” compared to 78% of heterosexual students. However, LGB+ students are much less likely to be sure that they would pursue a law degree if they could start over. Just under three-quarters (74%) of LGB+ students said they would pursue a law degree and 19% were unsure. More than four in five (82%) heterosexual students would choose law school again and only 14% were unsure. Clearly, LGB+ law students are more likely than heterosexual law students to have regrets or misgivings about the path they selected.

Given that the population of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and other non-heterosexual students is growing rapidly in law schools, the concerns that these students have about the law school experience deserve particularly careful attention. LGB+ law students are less likely to feel that they belong, more likely to feel stigmatized, and more likely to question whether attending law school was the correct choice for them. Interestingly, most LGB+ students feel that their instructors care, and they are equally likely as heterosexual students to have an instructor that they consider a mentor. Perhaps law schools can use these personal connections to identify and address the concerns of their lesbian, gay, bisexual, and other non-heterosexual students in order to ensure equitable educational opportunities and a more supportive law school environment.

Guest Post: The Normative and Legal Case For Affirmative Action Programs for the Descendants of Persons Enslaved In America

Guest Post: The Normative and Legal Case For Affirmative Action Programs for the Descendants of Persons Enslaved In America

Erika K. Wilson

Professor of Law, Wade Edwards Distinguished Scholar, and Director of the Critical Race Lawyering Civil Rights Clinic

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

The Supreme Court’s recent decision in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President & Fellows of Harvard Coll., 143 S. Ct. 2141 (2023) arguably ended race-conscious admissions policies as we know them. While the Court did not expressly overrule diversity as a compelling state interest, it did find that the way in which Harvard and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill were using race to achieve diversity was unconstitutional. The majority opinion observed that universities undermined their stated interest in obtaining a racially diverse class by relying upon “opaque racial categories.” It identified as particularly problematic categorizing all Asian applicants together with no distinctions made between South and East Asians; the arbitrariness of the Hispanic categorization; and the under inclusiveness of the Middle Eastern classification. Justice Gorsuch’s concurring opinion made a similar observation with respect to the categorization of Black students:

The “Black or African American” category covers everyone from a descendant of enslaved persons who grew up poor in the rural south, to a first-generation child of wealthy Nigerian immigrants, to a Black-identifying applicant with multi-racial ancestry whose family lives in a typical American suburb.

Gorsuch’s critique is salient because the original purpose of race-conscious affirmative action programs was to remediate the multi-generational effects of slavery and the afterlives of slavery. Yet, as documented by legal scholars like Angela Onwuachi-Willig, in the early 2000s Black students at elite universities were overwhelmingly mixed-race students, or first- or second-generation Black Americans, meaning their parents and/or grandparents were immigrants. Lani Guinier and Henry Gates raised concerns in 2004 because only one-third of Harvard’s Black undergraduate students were from families in which all four grandparents were born in America, descendants of persons enslaved in America.

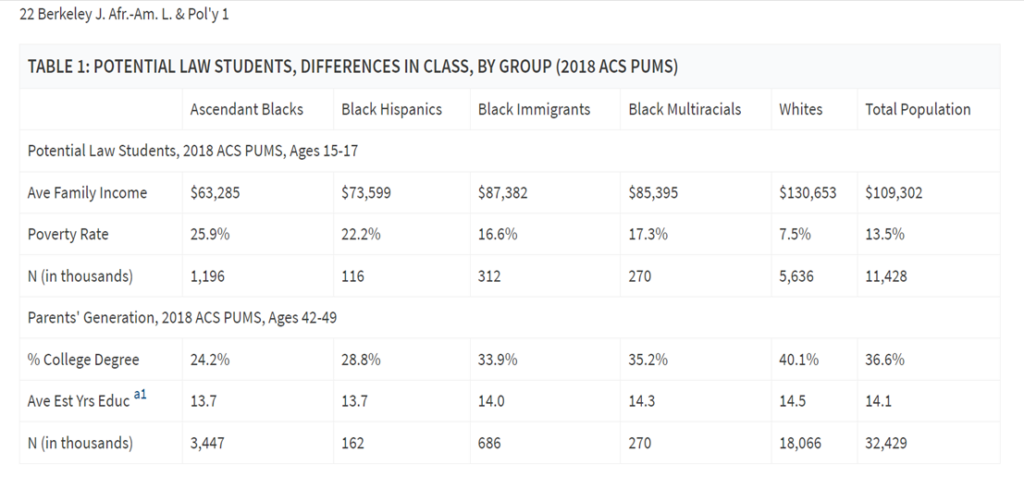

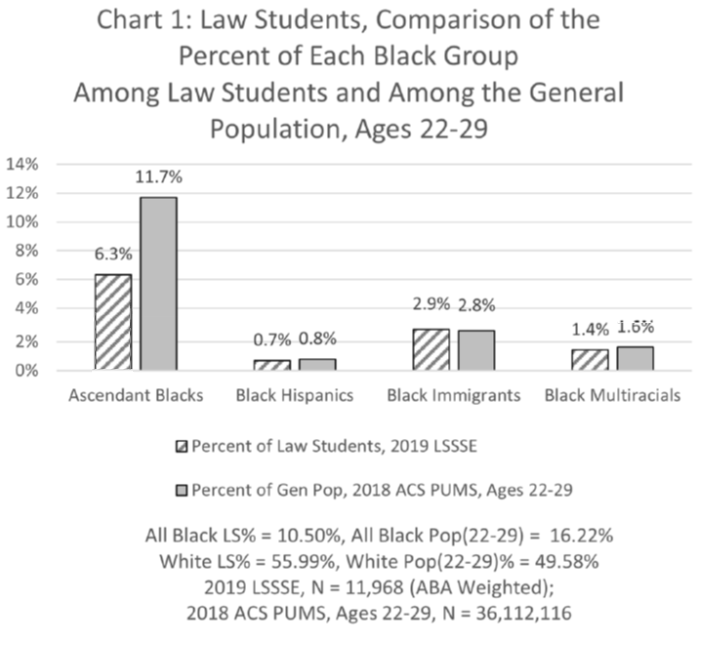

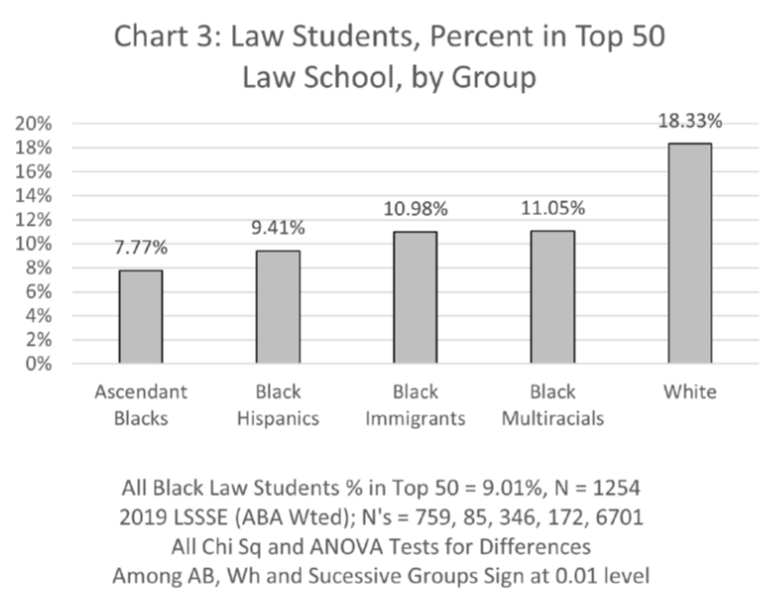

Recent research by Kevin Brown and Kenneth Dau-Schmidt relying on LSSSE Survey data shows that not much has changed since the early 2000s. Similar patterns of disproportionate representation of what Brown and Dau-Schmidt call “ascendant Blacks” (those with two American-born Black (non-biracial) parents) exists in law school enrollment today. The data show three noteworthy trends:

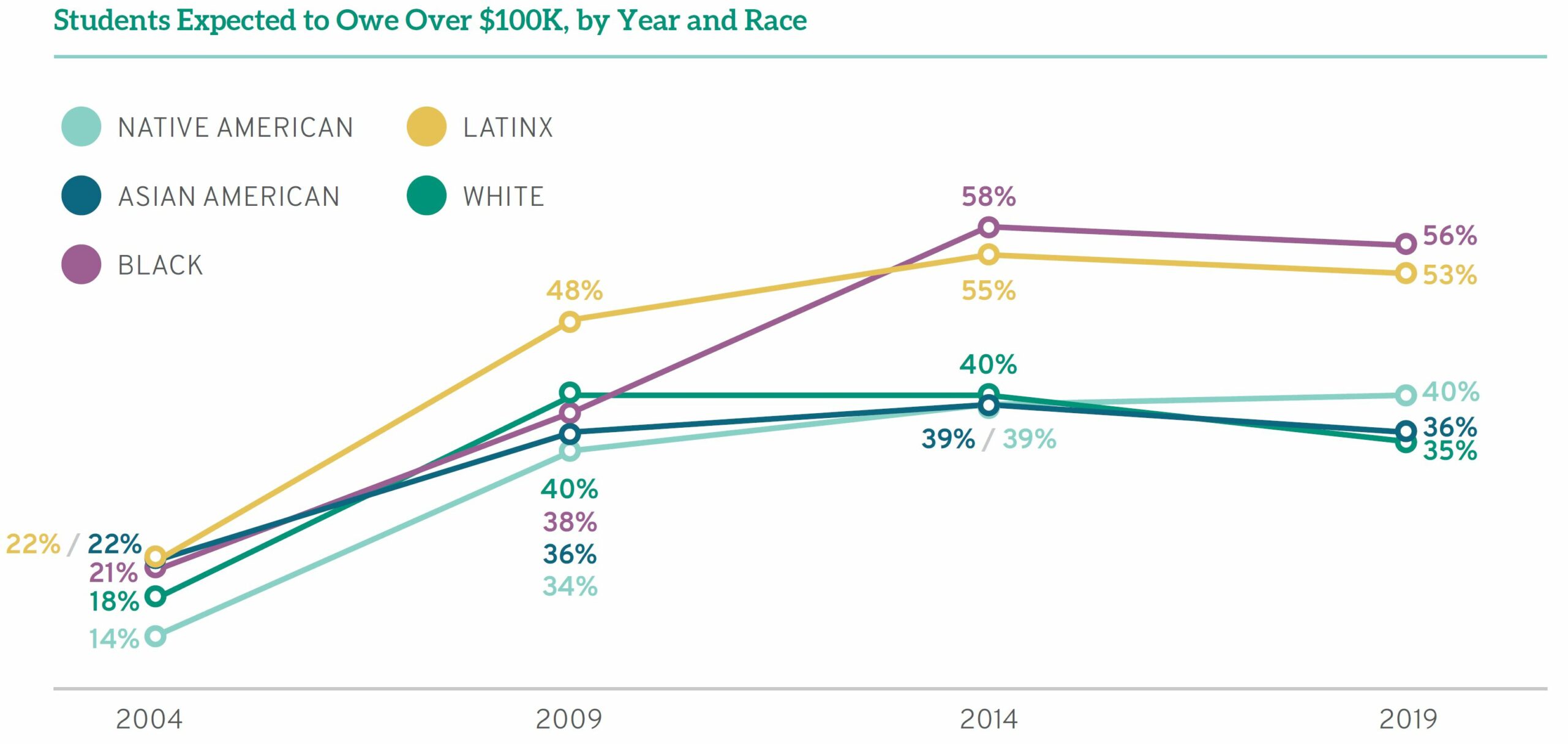

First, while structural racism impacts all Black people in America, it impacts some groups more acutely. As they write in their article, ascendant Black law students have lower average family incomes, higher poverty rates, and are less likely to have parents with a college degree.

Second, all Black people, except Black Immigrants (defined as Black people with at least one parent not born in America), are underrepresented among law students; furthermore, the extent of underrepresentation is much worse for ascendant Black law students than for other Black law students.

Third, ascendant Black law students are underrepresented at Top 50 law schools relative to their representation within the population of Black people in America, and relative to all other groups of Black law students.

The data and their implications should inform the path universities take to reinvent their affirmative action programs. Diversity is still recognized as a compelling state interest. Universities can and should fashion admissions programs that seek to increase representation of Black students who are the descendants of persons enslaved in America. To be sure, they should also continue to make efforts to increase representation of all Black groups because race remains a salient and undeniable barrier for all Black people in America. Yet the unique burdens and history of subordination linked directly to American slavery imposes a special remedial obligation on universities to provide access to Black students who are the descendants of persons enslaved in America. This is especially true for elite universities such as Harvard and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill that directly benefited from slavery.

In Justice Clarence Thomas’ concurring opinion in Students for Fair Admissions, he offers a potential Constitutional path for doing so. He suggests that a classification consisting of descendants of persons enslaved in America is not a racial category. He contends that:

[The 1866 Freedmen’s Bureau Act ] applied to freedmen (and refugees), a formally race-neutral category, not [B]lacks writ large. And, because “not all [B]lacks in the United States were former slaves,” “ ‘freedman’ ” was a decidedly underinclusive proxy for race.

His comments, as other scholars have noted, raise questions as to the legality of an affirmative action program centered on descendants of persons formerly enslaved in America, as such a categorization may not be subject to the same level of heightened scrutiny as a race-based classification. Nonetheless, Thomas’ assertion that “freedmen” was not a racial categorization is admittedly dubious. But such a targeted program might also be justified under the remedial justification for race conscious policies. Thus, universities should take Thomas seriously. They should fashion admissions programs aimed at increasing the representation of Black students who are the descendants of persons enslaved in America. LSSSE data and history demonstrate the normative case for doing so.

Extracurricular Activity Participation Among JD Students

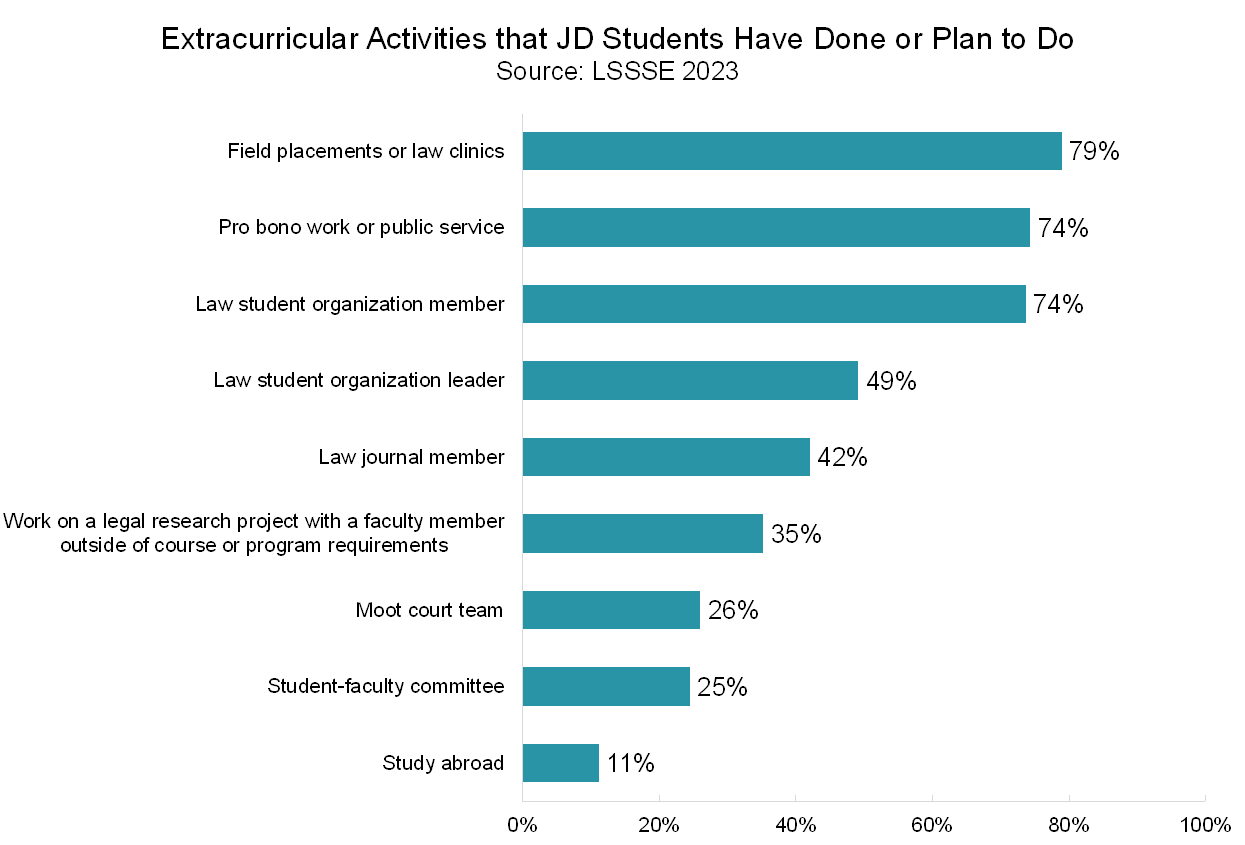

Although reading, class preparation, and classroom engagement are crucial to law student success, extracurricular activities provide unique experiences for hands-on learning and skill development. LSSSE asks about the activities in which law students have either already participated or plan to participate in the future. Which activities attract the most law students?

The majority of law students plan to complete a field placement (79%), engage in pro bono work or public service (74%), and join a law student organization (74%) before graduation. Around half of law students will be or already have been a law student organization leader, and around two in five are drawn to serving as a law journal member. However, students are somewhat less likely to include moot court and working with faculty members on research or committees in their extracurricular plans. Most law students do not plan to study abroad.

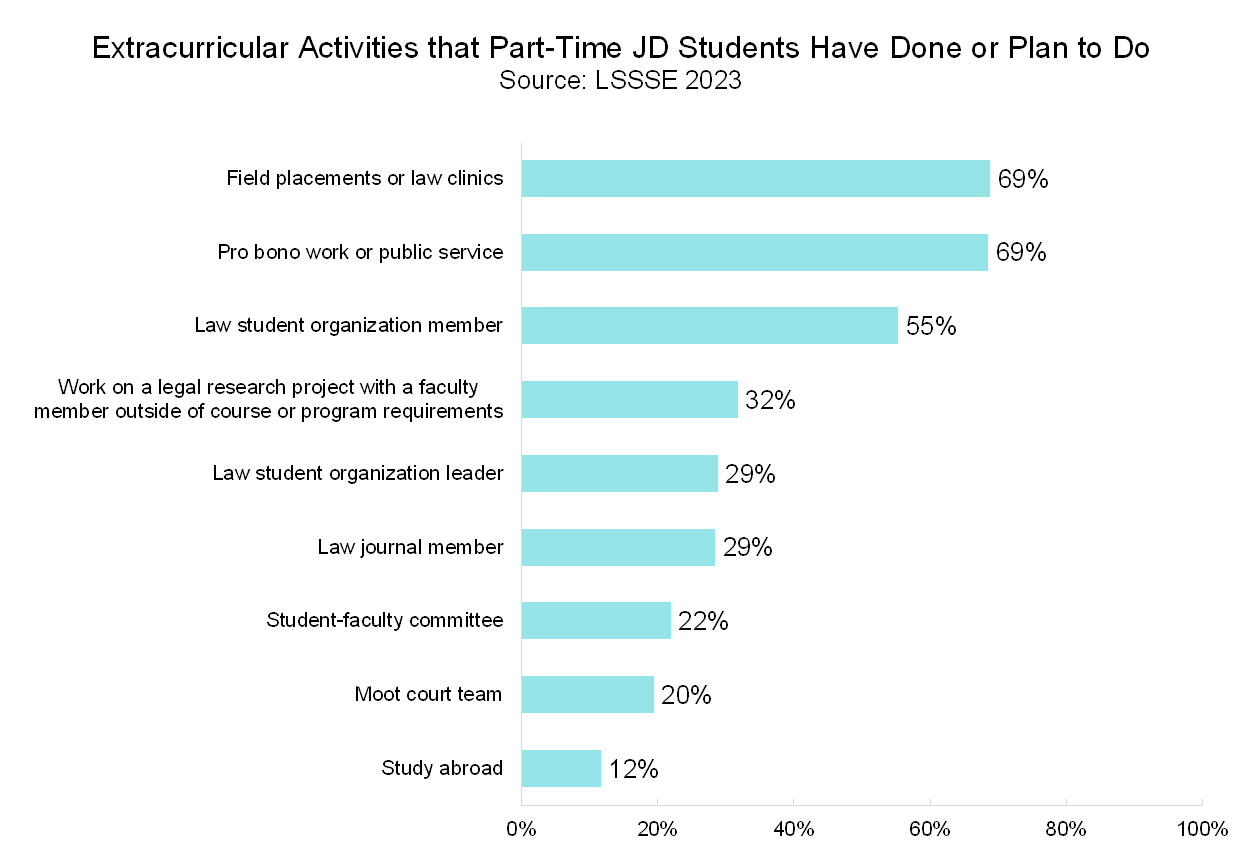

We know from previous LSSSE research that part-time students are somewhat less likely than their full-time classmates to engage in extracurricular activities. When we zoom in on part-time students specifically, which activities do they tend to make their highest priorities?

Field placements, pro bono work, and law student organization membership remain at the top of the list for part-time students. However, only about half of part-time students plan to join a student organization. Around a third (32%) of part-time students are interested in working on a legal research project, and around three in ten part-time students (29%) either have been or want to be a law journal member.

Clearly, being a law student is not a 9-5 endeavor. Most law students are engaged in a variety of activities beyond the bare minimum of class attendance and participation. These activities provide them with vital experiences and professional contacts that they will take forward into their legal careers.

Guest Post: Legal Education During the Pandemic: The Experiences of Latinx Law Students

Raquel Muñiz

Assistant Professor

Lynch School of Education & Human Development and School of Law (by courtesy)

Boston College

Andrés Castro Samayoa

Associate Professor of Higher Education

Lynch School of Education & Human Development

Boston College

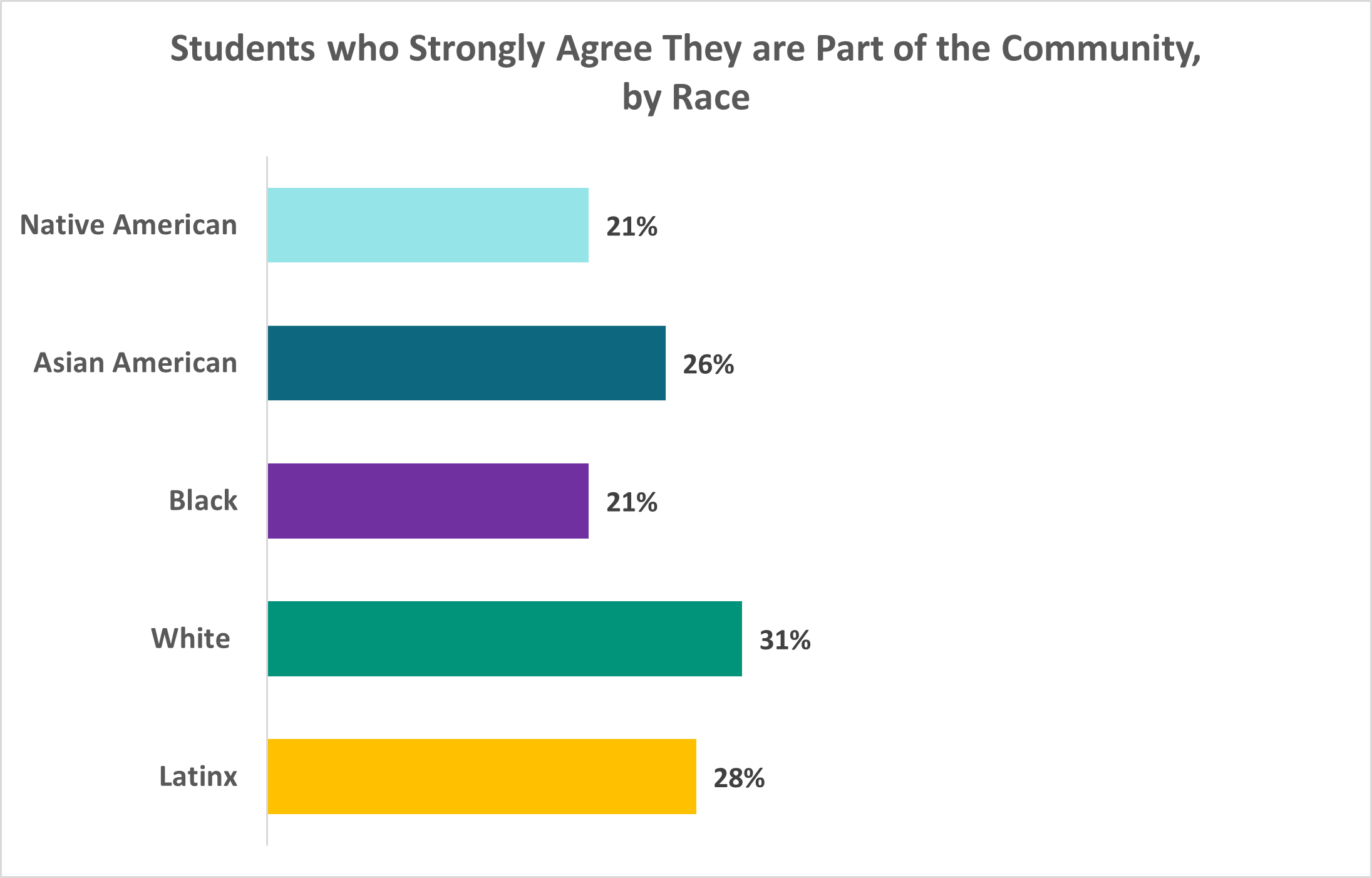

Latinx people remain underrepresented in the legal profession and experience exclusion and marginalization during law school. The culture and environment unique to legal education present challenges to their experiences. For instance, LSSSE data show that in 2020 only 28% of Latinx law students strongly felt part of their law school community and only 1 out of 5 Latinx law students reported feeling comfortable being themselves at their institutions. Moreover, while Latinx representation in law school has increased over time, they carry greater financial burdens. LSSSE has found that Latinas are more likely to borrow over $200,000 than men of the same ethnicity or than women from any other background. This troubling trend remains consistent in longitudinal reporting. Latinx law students remain a student population in need of structural support to access and succeed in law school as they are socialized into the profession.

In 2019, we began a project to understand how Latinx law students across differently ranked law schools (Tier 1, 2, 3 & 4) valued their legal education. We recruited students at law schools enrolling the largest proportion of Latinx law students across each Tier, two schools per tier. In total, we interviewed 81 law students: T1 (23 students total), T2 (23), T3 (24), and T4 (11). Our data collection extended into 2020, giving us a rare insight into how Latinx law students made sense of their legal education as the height of the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded.

Students were generally satisfied with the prompt response that their law schools employed as they shifted from in-person to virtual classes. They also agreed that a law degree is a timeless degree because, as a student noted, “[T]he world is always going to need attorneys.” Additionally, law students experienced the same disruptions as other students—disruptions to their routines, challenges concentrating and finding a space to study, as well as loss of community with other students, faculty, and staff. One noted: “It’s a loss of sense of community. It’s hard for you to keep in touch with your peers. It’s very difficult. It’s kind of like you’re just watching a YouTube video of the doctrine.” These trends align with LSSSE’s report, The COVID Crisis in Legal Education, which revealed numerous challenges including increases in loneliness and inability to concentrate.

In-depth qualitative interviews with 2Ls and 3Ls also revealed how the pandemic amplified challenges endemic to legal education, namely: a zero-sum hypercompetitive environment driven by hierarchical metrics of prestige as proxies of success. Students’ references to these concerns expressed themselves differently depending on their law school’s rankings. Student concerns in Tier 1 law schools centered around whether online courses would impact student learning, grades, bar passage rates, and subsequently law school rankings. Law school rankings were important to students in highly ranked law schools, because they viewed them as deeply intertwined with premium post-graduation employment opportunities. One student articulated this concern, noting:

I think as a law student, it makes me feel better about the money I’m taking off to go to law school, because they’d make me feel like people will want to hire me because of the school ranking. . . . I’m just really concerned about COVID and how that’s going to affect the rankings and schools and the type of student [learning.] I just feel like we’re better students when we do in-person classes. . . . It will affect the bar passage rate and, in consequence, school ranking.

These concerns were magnified in T1 schools compared to other law schools: Students expressed concerns that their law school would fall in the rankings as a result of COVID and that the money they paid (and often, borrowed) to attend a highly ranked law school would not yield results, leading to fewer professional opportunities. Tier 2 law students expressed a more salient concern with disruptions to the relationships they had built through experiential learning and summer placements. They also worried about the high cost of attending law school and whether that was a worthy investment or if COVID would diminish their investment.

In contrast, students in one of the T3 law schools had a heightened awareness of their schools’ lower ranking and worried that jobs in the legal profession would shrink because of COVID and the few positions left would go to students in higher ranked law schools. The second T3 school was heavily focused on public interest law, and students repeatedly noted that their degree post-graduation was even more valuable, because there is an increasing need for lawyers who advocate for the rights of marginalized communities. Concerns over job prospects as a result of the pandemic were consistent in both T4 law schools.

While law schools continued to pivot to online learning and maintain a semblance of structured routine, within-class rankings became a topic of debate fueled by competition. Students in schools with class rankings across all tiers discussed their concerns with the Pass/Fail system adopted by schools. Multiple students shared that the lack of grades would lead to decreased motivation for students to excel academically. Others expressed a preference for grades, because this meant they would be able to outperform their peers and this would benefit their class ranking. This dominant sentiment is captured by a student in a T3 law school:

There's been some concerns about the grading system, because schools nationwide have decided to go to Pass/Fail or Credit/No Credit. . . . [T]hat created a lot of buzz and a lot of anxiety . . . . [There were] Facebook debates on: What’s better? What’s worse? And some folks are saying on Facebook that people of color have it harder and that we should just do Pass/Fail. Whereas my perception of this was: given the fact that I have actually been through a lot personally, I felt like I was actually looking forward to this. Because I felt like people that have not experienced adversity, right now, they’re facing it. And I know what it’s like to have to think on your feet. So, I was thinking to myself, “Well, go ahead, bring on the grades.” Like, we’re just going to see who can do what they can do.

Students’ responses to the early days of COVID reveal how even unexpected global disruptions can serve to further entrench the hyper competitive economy of prestige in preparing future lawyers. Four years into COVID-19, few institutional practices have attempted to curtail these efforts. In the past few months, the specter of artificial intelligence platforms like ChatGPT once again offer an opportunity to reconsider how we can equitably respond to the future of the profession. Will we heed the call?

Acknowledgement: This project was funded by AccessLex/AIR and The Spencer Foundation.

Law Students are Generally Quite Happy Wherever They Land

The choice of where to apply to law school is an important one. When evaluating law schools, most prospective law students thoroughly research the quality and reputation of the program, the extracurricular and employment opportunities it may provide, the campus climate, the cost of living, and other personally relevant factors. After applying, students must choose among the offers of admission they receive, which may or may not include an offer to their first-choice law school. We wanted to know how law students fare after matriculation. Does attending a first-choice or a non-first-choice law school have a large impact on student satisfaction? Do students who are attending their second or third choice have regrets, or would they make the same decision if they could start over again with the benefit of hindsight?

LSSSE includes the following three questions that help us disentangle several factors related to law school choice and satisfaction:

- Was the law school you are attending your first-choice law school as an applicant? Response options: No, Yes

- If you could start over again, would you attend the SAME LAW SCHOOL you are now attending? Response options: Definitely no, Probably no, Probably yes, Definitely yes

- How would you evaluate your entire educational experience at your law school? Response options: Poor, Fair, Good, Excellent

If you could start over again, would you attend the SAME LAW SCHOOL you are now attending?

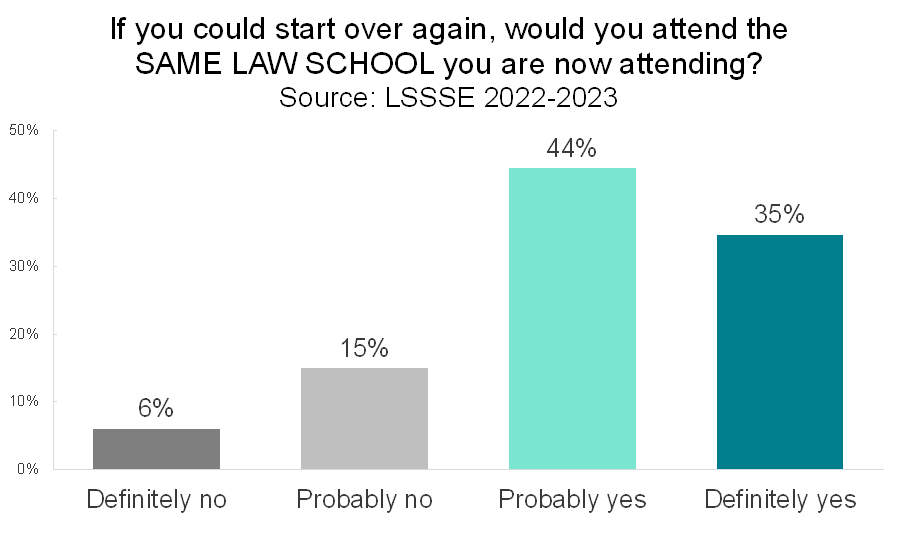

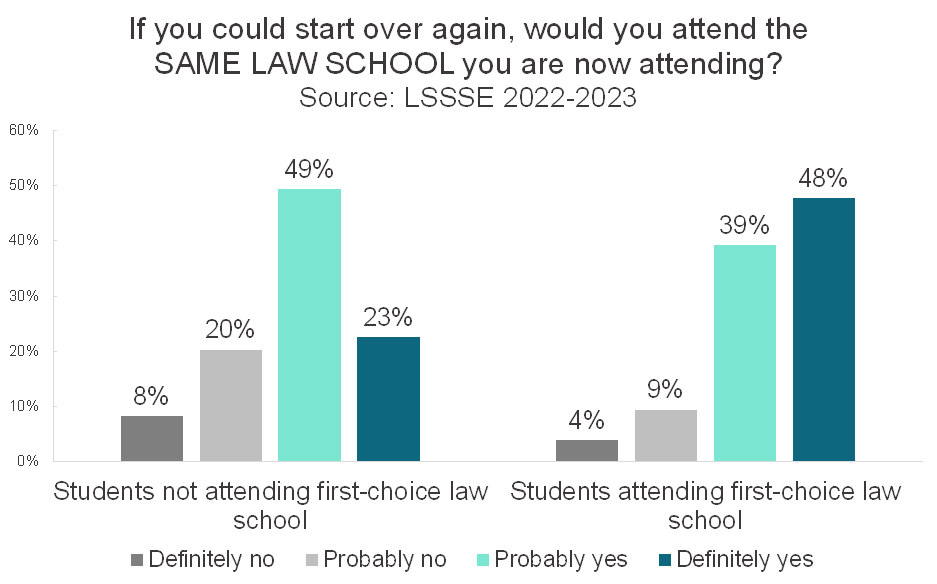

Slightly less than half of law students attend their first-choice law school. Among students surveyed in 2022 and 2023, 52% of law students were not attending their first-choice school compared and 48% of law students who were. Across the entire population, most law students would choose the same law school if they could start over again. Nearly four out of five (79%) of law students would probably or definitely attend the same school. A mere 6% of law students definitely would not.

Understandably, students attending their first-choice school were highly likely to say that they would make the same choice of law school again. A full 87% of these students would probably or definitely choose their law school again, and only 4% definitely would not. However, remarkably, students not attending their first-choice school were also quite likely to say that they would attend the same school if they could start over again. Nearly three-quarters (72%) of students not attending their first-choice law school would likely choose the same law school they are attending if they could start over. Only 8% of students at their non-first-choice school would definitely not choose to attend that school, and one in five (20%) said they probably would not

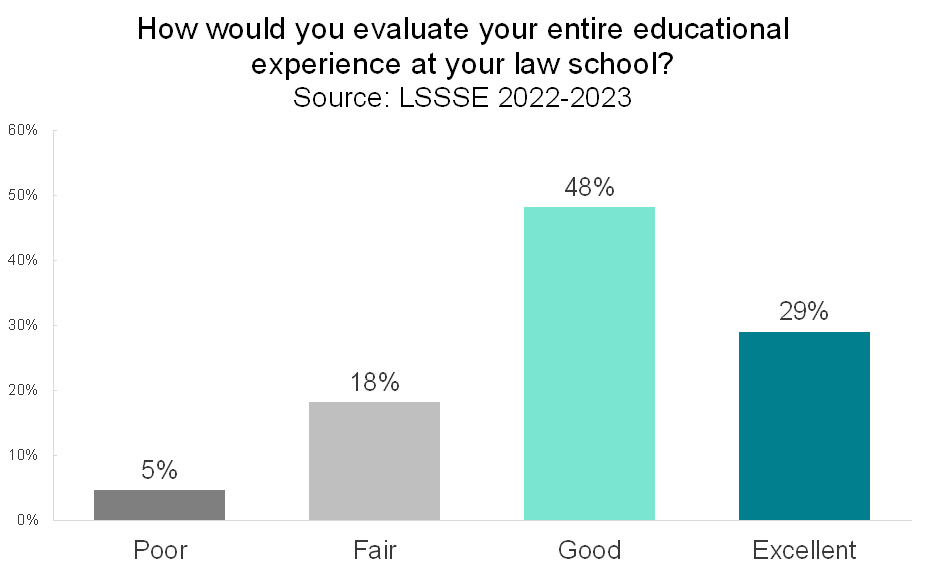

How would you evaluate your entire educational experience at your law school?

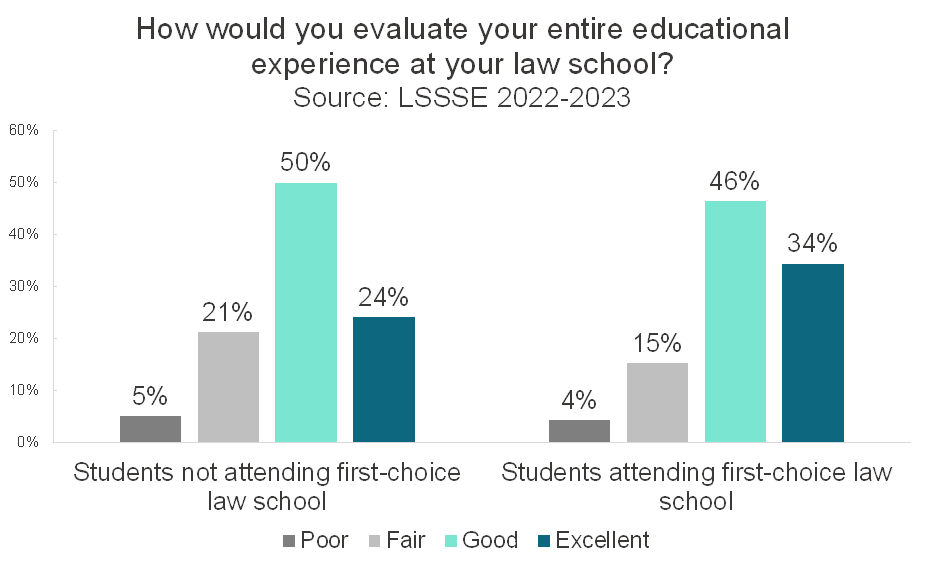

LSSSE has found consistently since the inaugural survey in 2004 that law students tend to be highly satisfied with their law school experiences. The two most recent survey years show that 77% of law students rate their experiences highly, with 48% saying their entire education experience is “good” and 29% saying it is “excellent.”

Again, there are disparities between students who are attending their first-choice law schools and students who are not, but the differences are quite modest. Eighty percent of students attending their first-choice school are satisfied compared to 74% of students not attending their first-choice school. A small and nearly equal percentage of students from both groups say that their entire educational experience has been “poor." It seems that most law students find ways to learn and thrive in the environment where they land, even if it not what they had thought would be their ideal situation before beginning law school.

Prospective law students should take heart in these findings. Although the choice of law school seems incredibly important during the application and admission process, most law students ultimately feel quite satisfied with their choice of law school, even if it wasn’t the school they might have preferred initially. And if they could start over, most law students would likely choose their own law school all over again.

Self-Check: Are We Paying Attention to Developments in the Profession?

Guest Post

Marsha Griggs

Associate Professor of Law

Saint Louis University School of Law

The BlueBook® is in its twenty-first edition and for the last fifteen years has been available online as well as in its original spiral-bound print version.[1] I could not imagine publishing a Law Review article, submitting a court brief, or teaching a Legal Writing course without consulting the most current edition of the BlueBook. Although I don’t care about uniform citation guides for my day-to-day writing tasks, I understand the expectation of proper citation for formal writing projects.

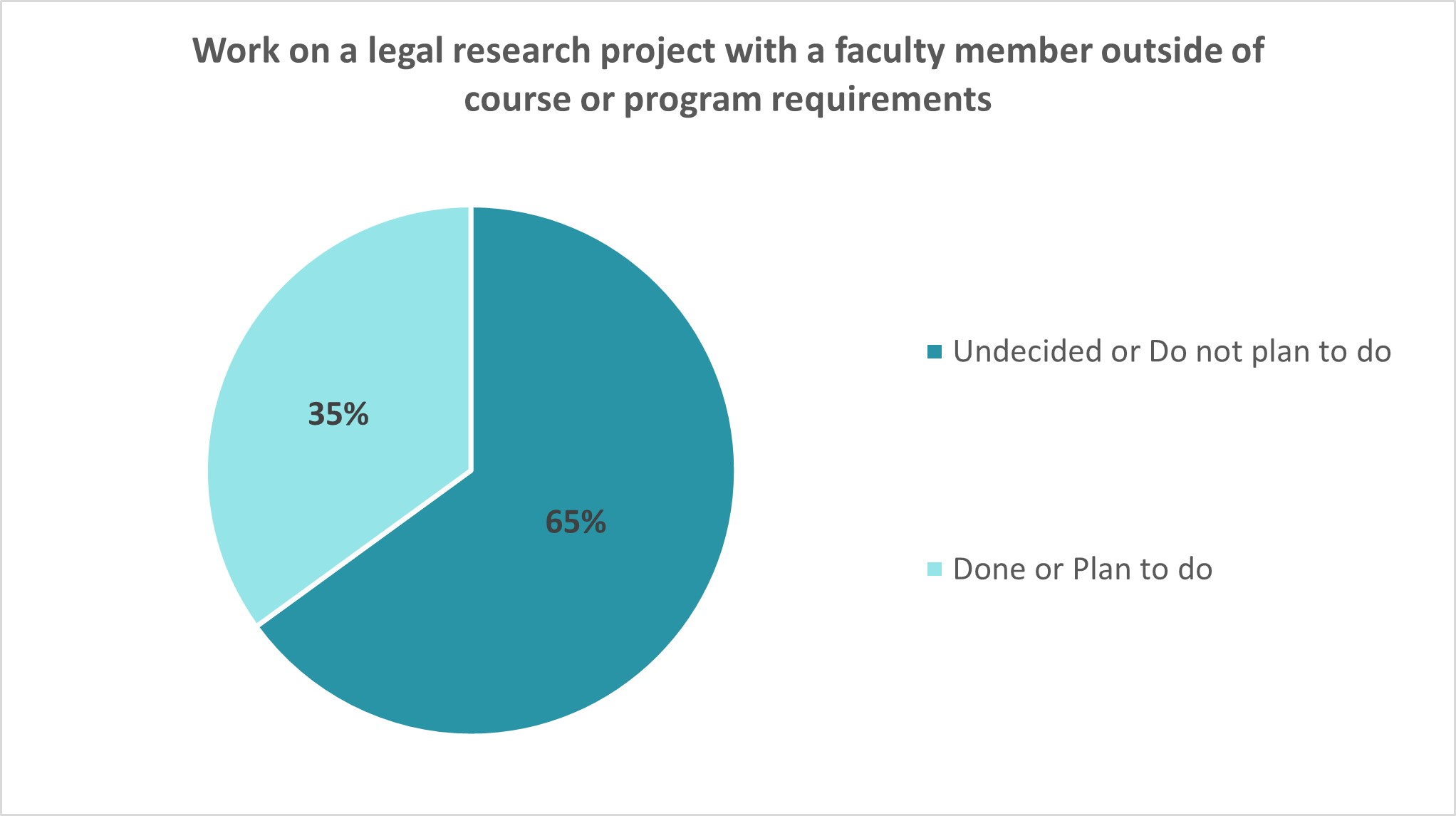

To meet that expectation, I gratefully rely upon my research assistants and the meticulous eye of journal editors. I am out of practice with my “blue booking” skills, because I consistently hire someone else to do it for me. I know that many other mid-career faculty and law practitioners can relate. Thankfully, LSSSE Survey data show that law students benefit from working on legal research tasks with faculty outside of class assignments. Although student research responsibilities for faculty and journals often fall outside the experiential education radar, these tasks are important to practice readiness.

While it is perfectly fine for me to outsource necessary cite checking to a student or even to an A.I. tool like ChatGPT, I am still ultimately responsible for my written product. The same is true about our professional responsibilities as lawyers. We can and should rely on available technology and skilled providers who can aid us in delivering legal services and establishing and enforcing laws and policies. But we must do so with a conscious awareness that tools, practices, policies, and laws are constantly subject to change.

Lawyers and legal educators have an ethical obligation to engage in continuing study and education to keep abreast of changes in law practice and legal rules, including the benefits and risks associated with relevant technology.[2] That obligation includes keeping up with changing rules for attorney licensure. Yet very few law professors and even fewer attorneys in practice understand the previous and proposed sweeping changes in attorney admission, including who creates and controls the bar exam.

Outsourcing a specific legal task—like research or cite checking, is not the same thing as outsourcing a regulatory function—like licensing attorneys. In a forthcoming article, Outsourcing Self-Regulation, I address how states have contracted with outside providers to produce bar exam questions and to score the exams. Like my outsourced blue booking, it saves time and results in a higher quality product. But when the outsourcing of a responsibility is combined with inattention or lack of supervisory accountability, it becomes delegation of a regulatory power or duty. Such a shifting of regulatory authority threatens the autonomy of the legal profession.

Today, bar exam questions are almost uniformly written and selected by the NCBE. [3] The NCBE has successfully lobbied for a single unform exam to replace the varied individual state law exams. The widespread adoption of a Uniform Bar Exam has privatized bar admission to the point that states no longer have control (or even input) into the content, scope, or timing of their licensing exam. The privatization of the bar exam is at odds with the cornerstone principle of resolute self-regulation and freedom from external influence.

The planned debut of the NextGen bar exam in 2026 threatens to further weaken the judicial autonomy in attorney admission.[4] Dangerously little is known about this new exam and law schools too are fully at the mercy of NCBE for crumbs of information about the next exam. We cannot effectively help our students to prepare for licensure if we ourselves are unfamiliar with the licensure exam and its format and cannot verify its validity.

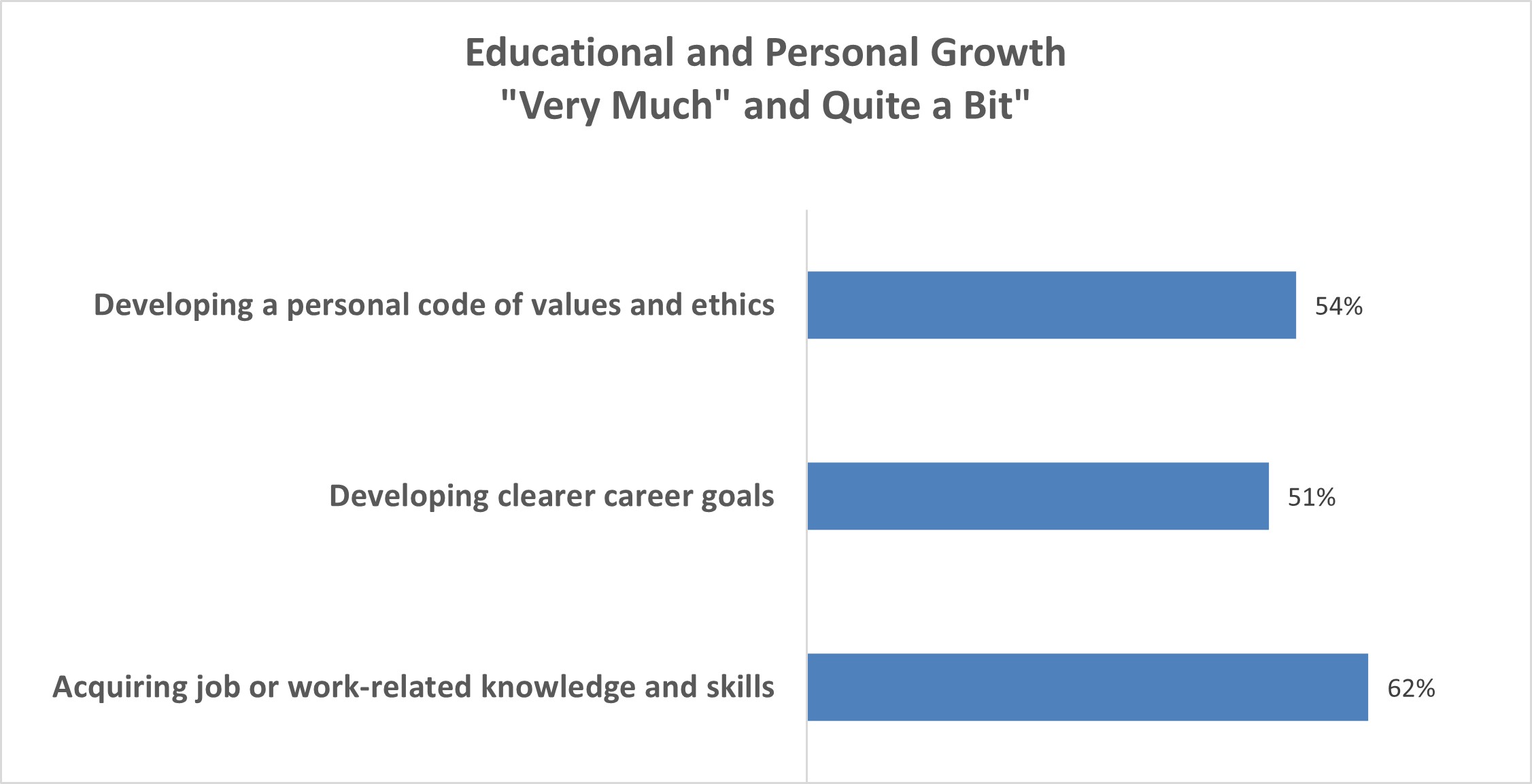

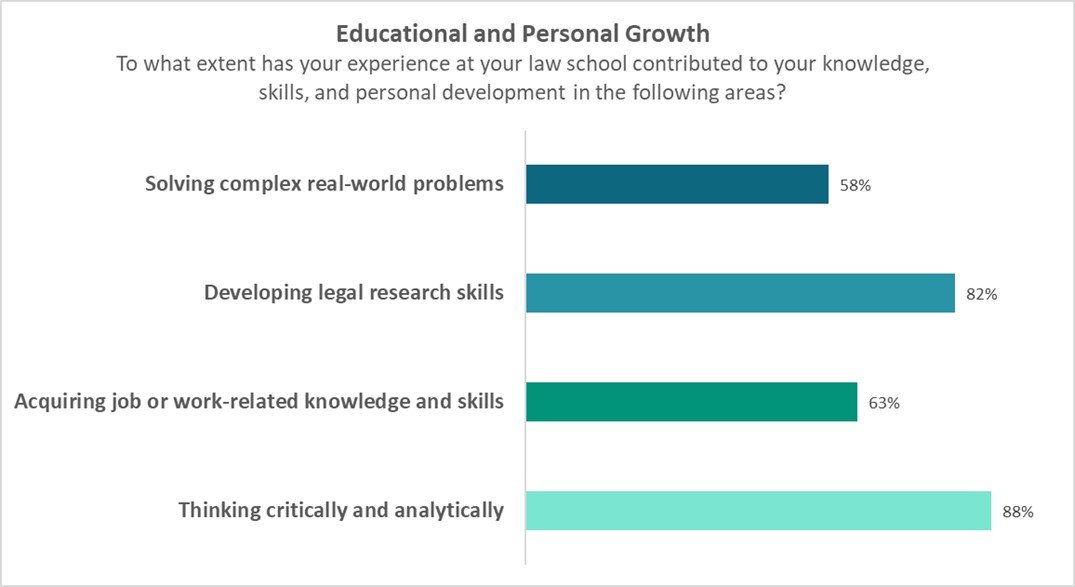

The LSSSE Survey data show that law students feel that law schools have generally prepared them for work-related tasks and supported them in developing career goals and personal ethics.

A quantifiable component of preparing law students for the practice of law is preparing them for the bar exam that allows them entry into law practice.

The pathway to becoming an attorney in the United States typically involves attending and graduating from law school, and successful completion of some competency assessment. All but a few U.S. jurisdictions use performance on a bar examination as a proxy for minimum competence to practice law. Since the genesis of licensure by examination, the format, content, scoring, and source of bar exams have been contentious issues in the legal profession.[5] The arguments for and against the use of bar exams are too great to list or summarize here, but—however it is measured—law schools are responsible for ensuring that their graduates are minimally competent to deliver legal services directly to clients upon completion of the program of legal education.

As members of a self-regulated profession, we have a responsibility not only to know about the scope of the regulatory exam, but also to set the standards for what the regulatory exam should measure and how it should do so. We must pay attention to developments in attorney licensing if we aim to continue to meet the needs of our students who will pursue licensure.

___

[1] The BlueBook: A Uniform System of Citation R.15.8(c)(v), at 154 (Columbia L. Rev. Ass’n et al. eds., 21st ed. 2020).

[2] American Bar Assoc’n Model Rule of Professional Conduct 1.1 Comment 8.

[3] The National Conference of Bar Examiners is a not-for-profit corporation with its principal office in Wisconsin. https://www.ncbex.org/about/media-kit/

[4] https://nextgenbarexam.ncbex.org/

[5] See e.g. Joan W. Howarth, Shaping the Bar: The Future of Attorney Licensing (2023), and Marsha Griggs, Building a Better Bar Exam, 7 Tex. A&M L. Rev. 1 (2019).

Classroom participation by gender identity: 2023 update

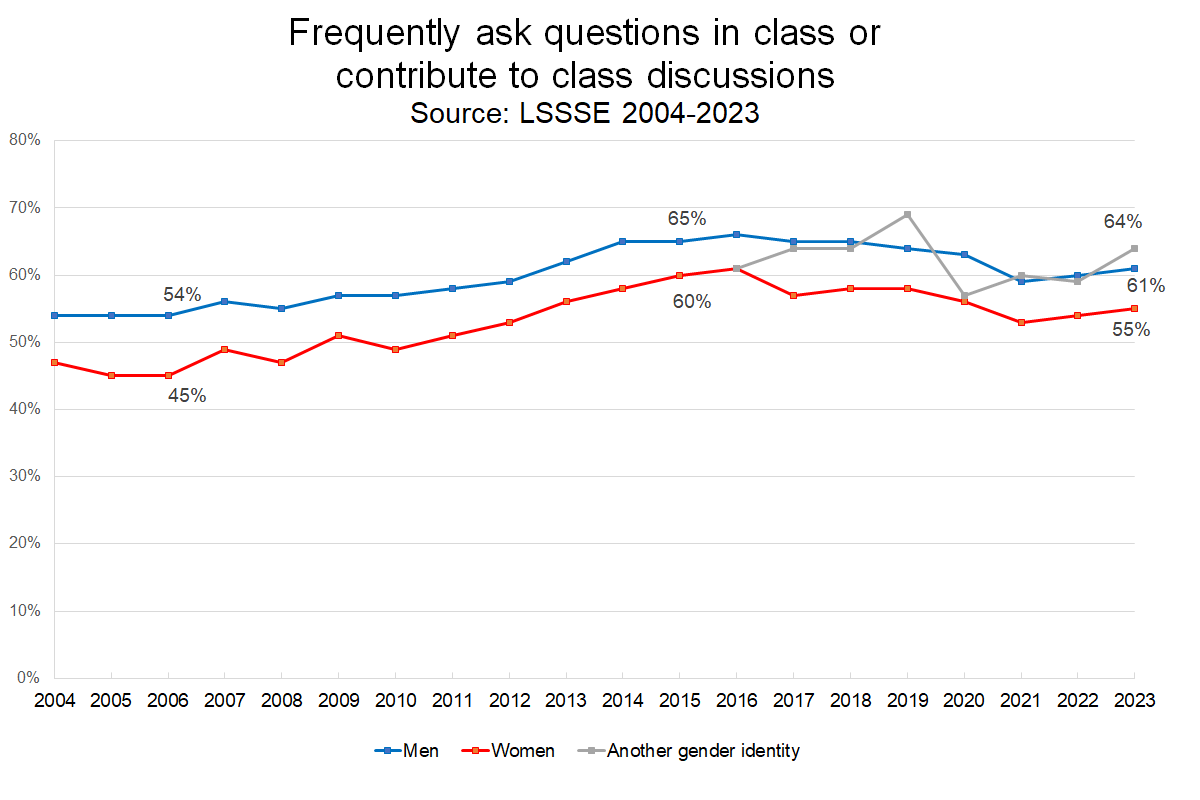

In a 2018 blog post, we showed a long-standing pattern of class participation by gender among law students in which men engage more frequently in class discussions than women. Although the percentage of students who frequently ask questions in class or contribute to class discussions has fluctuated over time, the gap between men and women has stayed remarkably consistent since the inaugural LSSSE survey in 2004. How does this pattern look five years later?

Through a pandemic, a switch to online learning, and a switch back to in-person learning, the pattern has continued to be remarkably consistent. In 2023, 61% of male law students “often” or “very often” participated in class compared to only 55% of female students. Students of another gender identity also generally participate in class more often than women, with nearly two-thirds (64%) of them frequently asking questions or contributing to class discussions in 2023.

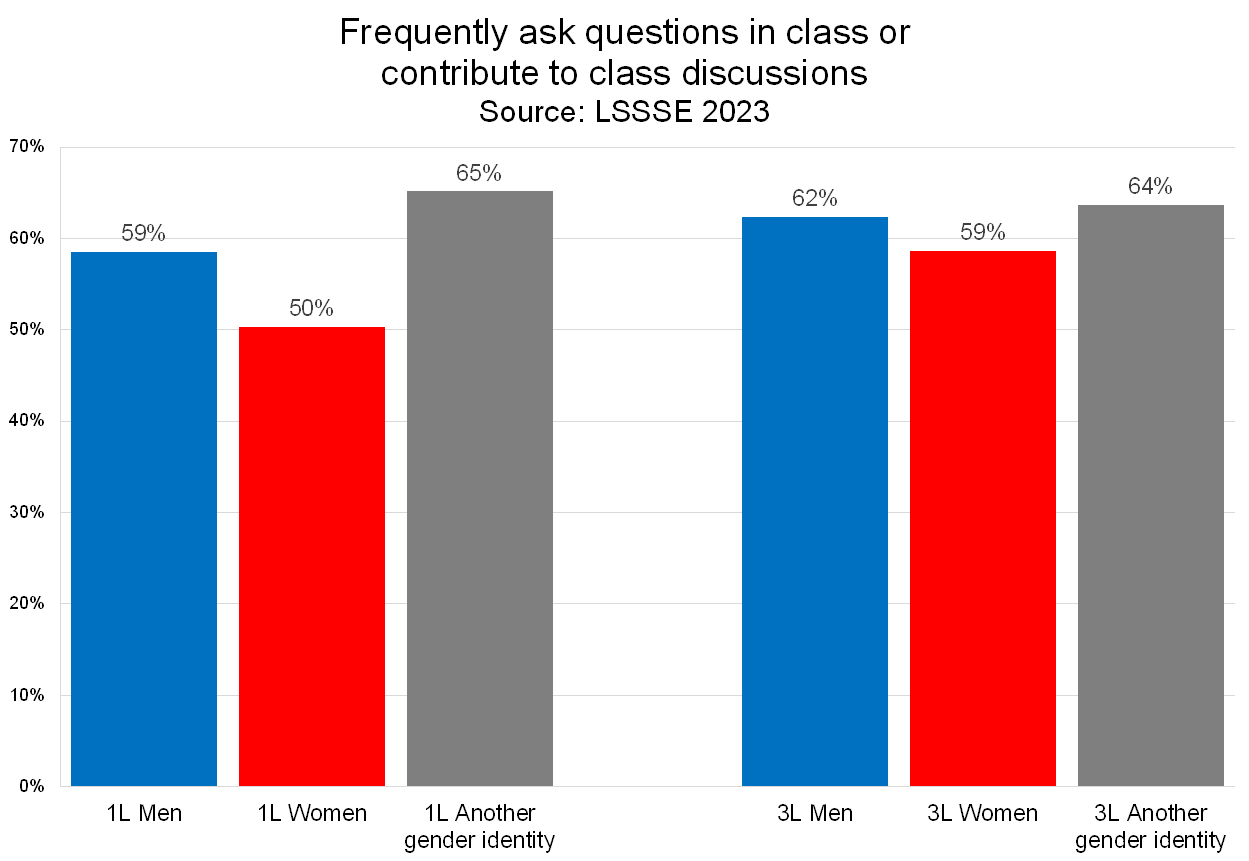

However, it appears that there are differences among classes in terms of participation by gender. 1L women are much less likely than 1L students of other genders to frequently ask questions or contribute to discussions, but 3L women are only somewhat less likely to do so relative to 3L students of other genders. Perhaps women gain confidence across their years as a law student or perhaps they become major contributors to class discourse only once they can be reasonably sure that their voices will be heard and respected.

Nonetheless, men and people of other gender identities are still slightly more likely to frequently ask questions or contribute to discussions even in that final year of law school. Finding ways to encourage women to participate in class conversations earlier will allow them to engage more meaningfully with their entire legal education in addition to elevating the discourse of the law classroom for all students.

The Power of Critical Legal Research

The Power of Critical Legal Research

Priya Baskaran

American University Washington College of Law

Every year students ask me which classes are “the most important” to prepare them for successful and fulfilling legal careers. Should they focus on Bar classes or load up on Business Law for future corporate practice? Or should they opt for a seminar that will really engage their interest in human rights or environmental justice? Inevitably many students seek me out because as a professor at the top ranked clinical program at American University Washington College of Law, I actively engage in the practice of law. I also closely supervise and ultimately grade my clinic students on their own lawyering skills. The students who seek my advice do so because they are keen to acquire the skills and training to lawyer well. My response often surprises students: Take an advanced legal research class and focus on Critical Legal Research.

Legal research is too often conflated with navigating a commercial search database as quickly as possible. In reality, legal research is a complex, dynamic, and iterative process that requires a combination of critical thinking, analysis, strategy, and perseverance. Legal research is also a large part of the average attorney’s work life, particularly early career attorneys.[1] Finally, and most importantly in my mind, developing strong legal research foundations is essential to solving complex, real-world problems. This latter point is only increasing in relevance with the continued growth of generative AI.

Legal research provides students with a primer in intersecting legal regimes, showcasing how various subjects we teach in self-contained classes actually combine and impact the facts of any given case or circumstance.[2] Legal research then teaches students how to critically examine and sort these intersections into tiers of relevance for their various research questions and research tasks. Finally, legal research focuses on creating search plans and strategies. This includes understanding where they find this information – specialized secondary sources, primary authorities practice related resources, even specialized databases. Students also actively analyze and evaluate the results of their searches, making thoughtful and critical determinations when sorting and prioritizing information.[3]

A properly taught legal research class excels in equipping students with the skills essential to good lawyering: 1) complex problem solving by researching messy or novel situations, 2) practical training in a core lawyering skill – legal research, 3) the ability to engage in active learning by directly researching, and 4) developing critical thinking and analysis skills. We see from LSSSE data that a majority of law students do learn these skills in law school.

*Students responding “quite a bit” or “very much”

In particular, a number of schools are increasingly using critical information literacy and Critical Legal Research to teach legal research. Critical legal information literacy is a pedagogy that challenges conceptions of legal research databases as neutral or comprehensive. Instead, critical information literacy teaches students that legal information is intentionally curated and categorized, often for commercial purposes.[4] This teaches students to be careful, thoughtful readers when their search results skew in favor of the status quo. Similarly, Critical Legal Research (CLR) builds on critical legal information literacy and incorporates critical legal theories and methodologies into the legal research process.[5] CLR challenges students to rethink their research questions, research strategies, and develop more expansive and thoughtful research plans in order to account for systemic bias. CLR underscores how the existing commercial search databases can entrench hegemonic interests, harming novel arguments that can advocate for more just outcomes.[6]

Take for example the case of a retail employee in June 2020. The employee works for a popular coffee chain that has been deemed “an essential business” during the COVID-19 epidemic. The employee routinely has to interface with customers who refuse to follow the safety protocols required by the county health department, including masking. Her manager requires employees still serve these customers despite the violation of the county health code and the CDC requirements. The employee finds her current work situation untenable for a number of reasons. First, she is deeply troubled by the request to break county law by violating the health department’s mandate. Second, she is concerned for her safety and the safety of her family (including an immunocompromised dependent). She feels like she has no choice but to quit her job but is worried about qualifying for unemployment insurance benefits.

We can immediately issue spot many complicated legal problems that will arise from this case. We can also identify the person being impacted by these “justice” issues – a worker facing both economic precarity and unsafe working conditions. Finally, we should be able to recognize that legal precedent will be exceedingly thin as June 2020 was still the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Building a case with little to no case law requires creative thinking and creative research strategies. What other sources may prove informative or be persuasive? Are there corollaries we can draw to other illnesses or other jurisdictions we should use to build our argument? Finally, we must identify and discuss that justice – when it goes against the dominant interests – requires creative and tireless advocacy on the part of the attorney.

Moreover, the continued growth of generative AI requires that we are even more thoughtful in training students.[7] A poorly trained student will use generative AI as a crutch, adding minimal to no value and simply regurgitating the algorithms findings. A well-trained researcher will identify the shortcomings of the AI tools, creating a comprehensive search plan and strategy that acknowledges and mitigates these flaws. For example, an AI tool may write a briefing memo summarizing the findings and state that the worker has little precedent and therefore a weak case. A well-trained researcher will be able to understand why this AI argument is insufficient for the client and for greater justice. The researcher may even be able to use this AI answer to play devil’s advocate, building a more creative response to counter the points generated by the status quo algorithm.

There is no shortage of conversation surrounding AI in law schools. In addition to discussing academic integrity and ethics, we must use this moment to explore critical pedagogies. How can we as professors help our students understand the blindspots of commercial AI? How can we train them to become better thinkers, lawyers, and advocates by exposing them to the limitations and injustice implications of both AI and traditional research? The answer may lie in leveraging critical legal information literacy and CLR in our own classes and pedagogies.

Although legal research is often limited to the first year curriculum, there are ample opportunities for instructors to engage with the topic in other courses. My forthcoming article, Searching for Justice: Incorporating Critical Legal Research in Clinic Seminar, includes a bibliography of scholarly work and pedagogical tools created by librarians and experts in the field. Professors can and should scaffold student learning by leveraging Critical Legal Research within their pedagogies, training more thoughtful and critical attorneys.

__

[1] Noting that new attorneys spend an average of one third of their time researching. Steven A. Lastres, Rebooting Legal Research in a Digital Age 3 (2013), https://www.lexis nexis.com/documents/pdf/20130806061418_large.pdf [https://perma.cc/SH5Q-Z2D3].

[2] THE BOULDER STATEMENTS ON LEGAL RESEARCH EDUCATION: THE INTERSECTION OF INTELLECTUAL AND PRACTICAL SKILLS (Susan Nevelow Mart ed., Heinemann, 2014). P. xii.

[3] Sarah Valentine, Legal Research as a Fundamental Skill: A Lifeboat for Students and Law Schools, 39 U. Balt. L. Rev. 173, 201 (2010).

[4] Yasmin Sokkar Harker, Legal Information for Social Justice: The New ACRL Framework and Critical Information Literacy, 2 Legal Info. Rev. 19,43 (2016-2017).

[5] .Nicholas F. Stump, Following New Lights: Critical Legal Research Strategies as a Spark for Law Reform in Appalachia, 23 Am. U. J. Gender Soc. Pol'y & L. 573, 603 (2015); Nicholas Mignanelli, Critical Legal Research: Who Needs It?, 112 LAW LIBR. J. 327 (2020).

[6] Nicholas F. Stump, COVID, Climate Change, and Transformative Social Justice: A Critical Legal Research Approach, 47 WM. & MARY ENVTL. L. & POL’Y REV. 147 (2022).

[7] For a fuller exploration of the intersection between generative and legal research, I recommend reading: Nicholas Mignanelli, Prophets for an Algorithmic Age, 101 B.U. Law Rev. 41, 44 (2021).

A CRT Assessment of Law Student Needs

Meera E Deo, JD, PhD

Meera E Deo, JD, PhD

The Honorable Vaino Spencer Professor of Law, Southwestern Law School

Director, Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE)

For over a century, American policy makers have recognized the need to provide personal support to students in primary and secondary school. Many states, including California, offer free or reduced lunch to students in need. Nurses and counselors are often available on campus to provide medical attention, academic guidance, and mental health support. Despite our clear understanding of the importance of these structures of support for children in the K-12 educational system, there are few mechanisms to support students in higher education. Yet many students in college, graduate school, and professional school also struggle to meet their basic needs.

In my new article, “A CRT Assessment of Law Student Needs,” and the accompanying Fact Sheet, I seek to convince policymakers that law students also need both administrative and legislative support to help them survive and thrive academically as well as professionally. LSSSE data show law students have been struggling to recover from the heightened challenges they endured during the early years of the pandemic. Struggles with food insecurity, financial anxiety, and emotional strain contribute to declining academic success, particularly for populations that were marginalized on law school campuses long before COVID. Legislative support is necessary to support students through this era so they can maximize their full potential.

Applying a CRT Framework

When we consider the CRT tenets of intersectionality and the compound effects resulting from those with devalued raceXgender characteristics specifically, it becomes evident that women of color law students are particularly at risk of falling behind or leaving law school altogether without greater support. The CRT concept of praxis further urges scholars to not only theorize about challenges and opportunities, but to put proposals into practice to achieve real change. Merging empirical methods with CRT, a new model of eCRT scholars “seek to rethink and change the premise of race scholarship in general by eschewing theoretical and methodological silos in pursuit of deepening our understanding of race and racism to advance racial justice.” Here, LSSSE data coupled with CRT theories are particularly instructive.

LSSSE Findings on Law Student Needs

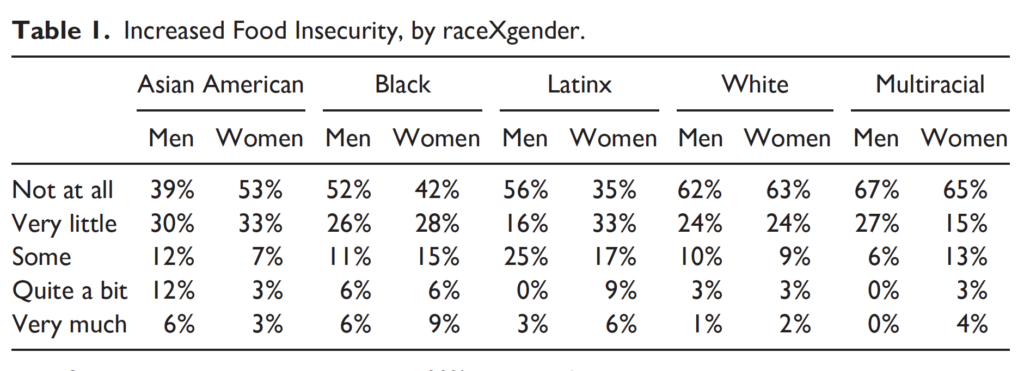

In 2021, LSSSE asked students about their experiences Coping with COVID. What they shared remains deeply disturbing, and even more so when we consider raceXgender effects. Women of color suffered with high levels of food insecurity—including 58% of Black women and 65% of Latinas who had increased concerns about whether they had enough food to eat.

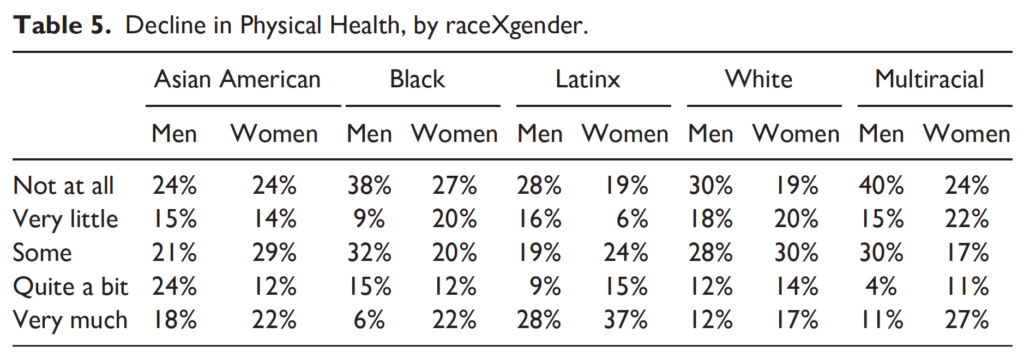

Students also reported declines in their physical health. For every racial group, higher percentages of women than men noted these declines—including 81% of Latinas (and 72% of Latino men).

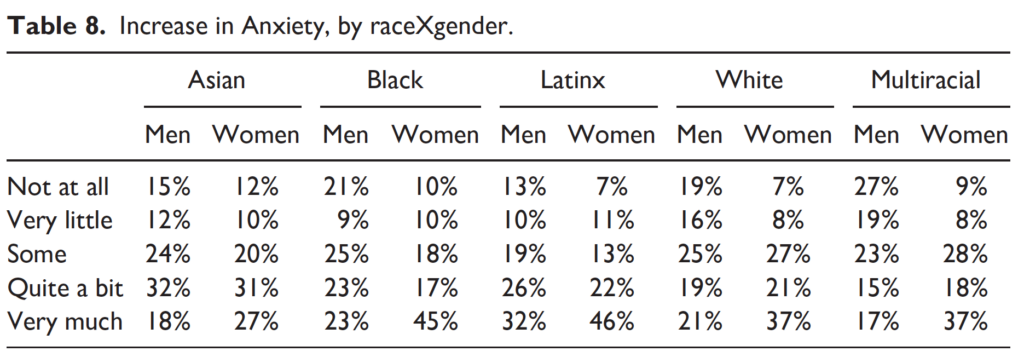

Most students also managed depression (85%) and anxiety (87%) that interfered with daily functioning—again, with marked raceXgender effects that bear out the CRT literature. For instance, while 73%–81% of white men, Black men, and multiracial men reported increased anxiety, a full 93% of white women, 90% of Black women, and 91% of multiracial women experienced the same.

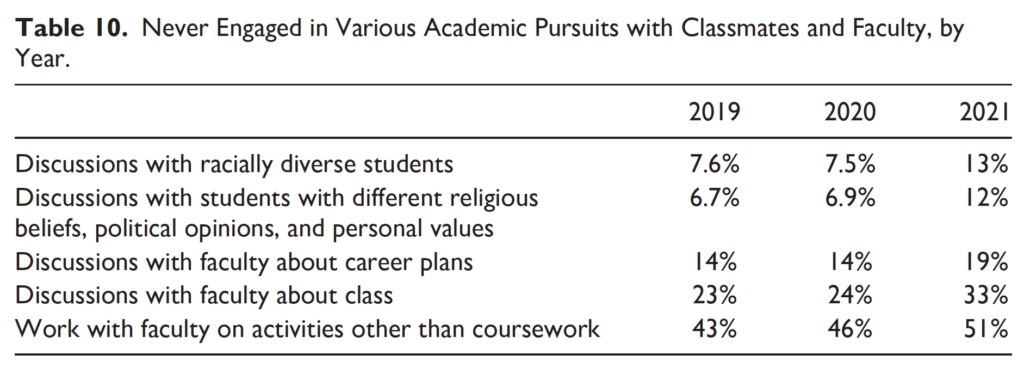

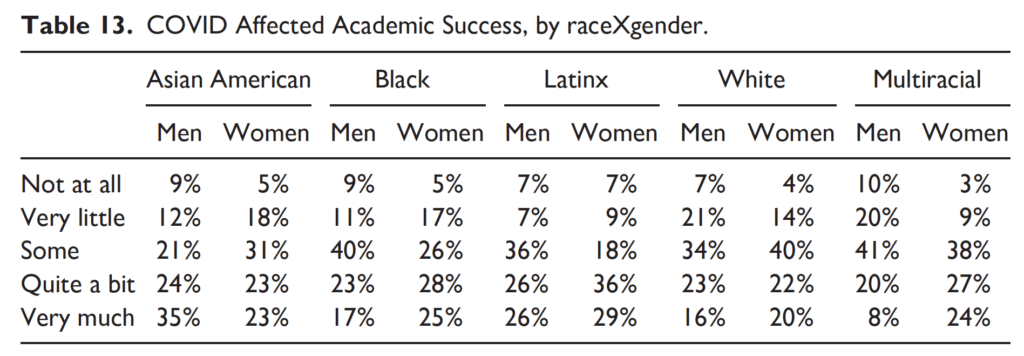

Struggles to meet their basic needs resulted in numerous missed opportunities for interaction with classmates and professors. One out of every five student respondents to the 2021 LSSSE survey (19%) never spoke with professors or other advisors about career plans or their job search. One third (33%) never discussed ideas from readings or classes with faculty members outside of class. There were also fewer opportunities for students to work with faculty on activities other than coursework (including committees, orientation, and student life activities); a full 51% of students never worked with faculty on these projects outside of class. Unsurprisingly, given all of these struggles, students also reported decreases in academic success, with women from most racial groups suffering more than men.

Institutional and Legislative Support

Most institutions already have a foundation to support students. But we can do better. In “A CRT Assessment of Law Student Needs,” I propose numerous options for administrators and policymakers to consider. For instance, while many campuses have food pantries to combat food insecurity, they should go beyond a locked room full of cans to prioritize accessibility by being open long hours or 24 hours, without an appointment or sign-in requirement, and on various parts of campus (not just one location that may be difficult for law students to access). Drawing from the CRT literature, food pantries should stock not only canned goods but also gift cards so students from varying backgrounds can purchase traditional or ethnic foods and fresh fruits and vegetables, and otherwise have agency over their food consumption.

Given increases in student anxiety and depression, law schools also should make mental health counseling available—with a focus on quality and accessibility for vulnerable populations. Counseling sessions should be free or low cost, with appointments scheduled via phone or through the click of a button, and meetings available both in person and online, as telehealth enables students of color—who rarely have on-site counseling available from professionals of their racial or cultural background—to connect online with counselors who work better for them.

Beyond institutional support, law students need legislative support. This is why the article includes an accompanying Fact Sheet—to make clear through brief bullet points and visualizations what the challenges are and how policymakers can help. Legislators could immediately reduce food insecurity by permanently expanding Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits to law students—without requiring them to work 20 hours per week or prove they care for dependents. Both the EATS Act and the Student Food Security Act provide pathways for SNAP expansion and extension; they are currently pending before Congress and should be strongly supported. California recently passed legislation expanding CalFresh (the state SNAP program) to those enrolled in institutions of higher education at least half-time. Other states should follow suit. Similarly, legislation should ensure mental health care is covered in standard insurance policies that tend to focus on physical health. Legislation could also offer financial assistance to institutions providing integrated mental health counseling for free or low-cost to law students. Additional legislative support could offer rental assistance, loan forgiveness, emergency funds, and other resources to law students in need.

Conclusion

Together, administrators and legislators can work to combat barriers facing law students that have intensified as a result of COVID. Once their basic needs are met, students can turn to maximizing their academic and professional success. Part of student success involves effectively and enthusiastically engaging in the intangibles of legal education, drawing from their own experiences and backgrounds to share and learn from classmates and faculty. When students are overcome by anxiety, depression, and loneliness, it is impossible to perform at their best.