Guest Post: Why Motivations Matter Revisited: More So Now

Guest Post: Why Motivations Matter Revisited: More So Now

Stephen Daniels

Senior Research Professor

American Bar Foundation

Shih-Chun Chien

Research Social Scientist

American Bar Foundation

In an earlier LSSSE guest blog post, we argued for greater attention to student motivations – to why people choose to attend law school and make a career in law.[1] We weren’t talking about just-so ideas of motivation like the “Trump bump”[2] or the escapist idea of avoiding a sour job market.[3] Such explanations, we said, “strip any real substance out of the idea of motivation, telling us little about the decision to attend law school and nothing meaningful about the choice of law as a career – and ultimately, this is the important issue.”[4]

We noted that “literatures in psychology and on organizations suggest that motivations can be important for understanding the outcomes of legal education, especially graduates’ career aspirations.”[5] Motivations become intelligible to the extent we can connect them to what students hope to do as lawyers.[6] The earlier blog was just the opening of a larger interest in motivation and the utility of LSSSE survey data, and this one furthers both.

Two LSSSE surveys are unique for exploring those motivations and career aspirations. One is older -- the 2010 LSSSE survey, and one newer -- the 2021 LSSSE survey. In addition to the full suite of annual survey questions (which included questions related to aspirations), each asked seven motivation questions to a subset of the survey participants. Those questions asked students to rate each of the seven motivations on seven-point scale from “not at all influential” to “very influential.”

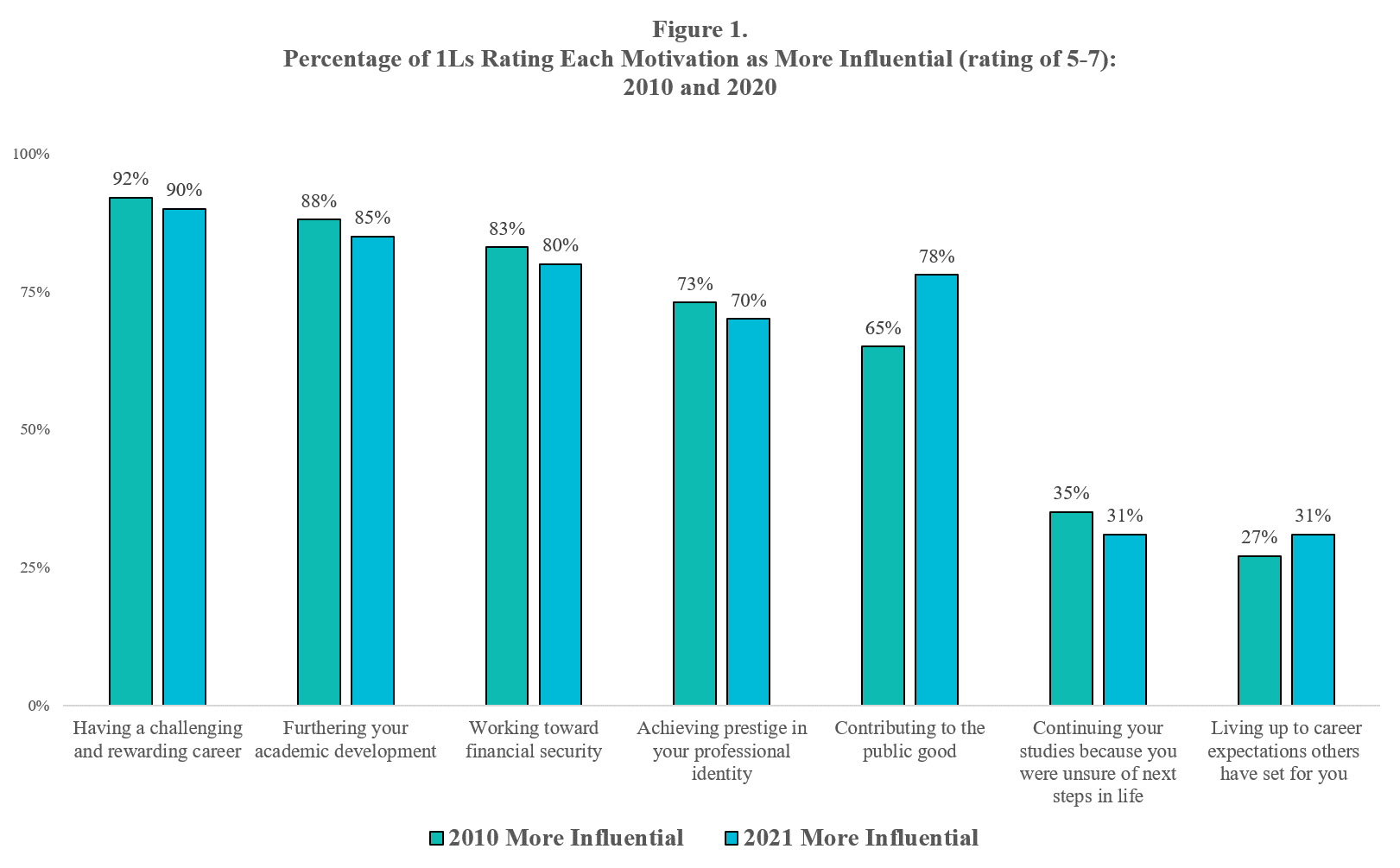

We delved into the 2010 motivation data just a bit in the earlier blog to illustrate the range of student motivations and their relative importance (4,626 respondents, 22 law schools) and we return to them here.[7] Figure 1 below shows the seven motivation questions and their relative importance for the students in the 2010 motivation subset. The percentages are for 1L respondents only -- they are closest to the decision to attend law school. Most important for the 2010 respondents are the intrinsic, inward looking, motivations of “a challenging and rewarding career” and “furthering one’s academic development.” The extrinsic, outward looking, motivation of “contributing to the public good” is much less important.

In a subsequent paper we began exploring that connection between motivations and aspirations using the same 2010 data.[8] Our interest there is in the links among motivations, preferred area of legal specialization,[9] and working in the criminal justice system, especially those wanting to work in a prosecutor’s office (or alternatively, in a public defender’s office).[10]

Viewed through the lens of motivation, those students in the 2010 motivation subset interested in criminal law saw contributing to the public good as a more influential motivation than did their peers interested in some other area of legal specialty. Their non-criminal law peers saw working toward financial security financial security as more influential.

Revealing a sharper contrast are the students interested in corporate and securities as their area of legal specialty. They are, in a sense, mirror opposites of the criminal law students in being driven much less by the public good, driven much more by financial security, and somewhat more by prestige. Only 39% of those interested in corporate/securities see public good as more influential compared to 72% for those interested in criminal law. The two groups of students clearly value different things and have different aspirations.

Having worked with the 2010 data and wanting something more contemporaneous, we asked the LSSSE administrators if they could add those seven motivation questions to the 2021 survey, and they generously did so. Those seven questions were asked to a subset of the 2021 survey participants (2,930 respondents, 15 law schools).

The 2010 data, while important in and of themselves, are just a snapshot in time. In wanting the 2021 data the key question for us is one about stability v. change. Are there any noticeable changes in student motivations, the interactions among motivations, and their connections to student aspirations? If so, what might help explain any change. The general patterns over time in the LSSSE data for job expectations would suggest relative stability rather than change.[11] Events in the broader societal environment since 2010 might suggest otherwise.[12] Our initial thought is the null hypothesis of no real change in motivations, which while generally the case isn’t in one important way. That exception involves the motivation of contributing to the public good.

Not only about the 2010 respondents, Figure 1 also presents a simple comparison of responses to the seven motivation questions in 2010 and in 2021 by 1L students.[13] The bars represent the percentage who reported that a motivation was more influential for them (a rating of 5, 6, or 7 on the seven-point scale). At first glance one sees a relatively stable pattern between 2010 and 2021, with small decreases in the degree of influence. The intrinsic motivations of a challenging career and academic development remain the most intense motivations followed by financial security.

One thing, however, stands out in an otherwise expected pattern of relative stability. Public good – an extrinsic motivation that is of particular interest to us – disturbs that pattern. Rather than the very slight decrease for the substantive motivations (all aside from “unsure of next steps” and “others’ expectations”), its influence is more important in 2021. Its influence became more important than prestige and close to that for financial security.

Digging a bit deeper into the data, we found that this increase does not appear to be just a matter of some general increase in the importance of public good. Instead, it is a matter of the intensity of the influence, and this is the most interesting finding. Again, the percentages in Figure 1 includes those giving a rating 5, 6, or 7. If we break that figure down, we see that the percentages for ratings 5 and 6 are essentially identical for the two years. For 2010, rating 5 = 17% and for 2021, rating 5 =17%. For 2010, rating 6= 17% and for 2021, it is 16%. For the highest, most intense rating we find 32% in 2010 and 45% in 2021. There is no comparable increase in intensity for the other substantive motivations (the greatest was for financial security, from 43% to 46%).

While our analyses looking at the characteristics of the students and schools involved in the two surveys are continuing, there are two matters worth noting concerning the public good, change, and intensity. Although quite different, both are instructive. The first involves gender. Female respondents rate the public good as more influential than their male counterparts in both surveys. For both groups, however, intensity increased as reflected in the percentage rating it at the highest ranking. In 2010, 37% of female respondents rated public good as very influential, while 23% of males did. In 2021, the percentages were 49% and 30%, respectively.

The second involves a very different way of looking at change and intensity – comparing students in particular schools rather than students in general. Two schools appeared in each motivation subset, allowing us to at least explore this. Because of the way in which LSSSE prepared the two data sets for us (using a unique code for each participating school that does not allow us to identify the school), we were able to find two schools appearing in 2010 and in 2021. For one of the schools the percentages of responding students rating public good at the highest level in each year are 25% and 41%, respectively. For the other school the comparable percentages are 20% in 2010 and 34% in 2021. Important here, as with gender, is not the exact percentages themselves (although those figures are not, of course, unimportant), but the idea of change in intensity even if the starting points were different. In short, something appears to be going on regarding student motivations.

Our comparative findings concerning change, though quite preliminary at this point, reinforce the importance of motivation for the study of legal education and the legal profession. An influx of students highly motivated by contributing to the public good has implications for both. It may shift the dynamics of the legal employment and increase the pool of graduates who aspire to much needed public service careers. At the same time, it means that law schools will need to provide the educational opportunities and support for those students to succeed, something not always the case. This could include working more closely with public service employers to provide needed opportunities and support.

___

[1] Stephen Daniels & Shih-Chun Chien, “Beyond Enrollment: Why Motivations Matter to the Study of Legal Education and the Legal Profession,” Guest Post, LSSSE Blog, September 24, 2020, ), https://lssse.indiana.edu/blog/guest-post-beyond-enrollment-why-motivations-matter/.

[2] Stephanie Francis Ward, “The ‘Trump Bump’ for Law School Applicants is Real and Significant, Study Says,” ABA Journal, February 22, 2018, https://www.abajournal.com/news/article/the_trump_bump_for_law_school_applicants_is_real_and_significant_survey_say; Karen Sloan, “Forget the ‘Trump Bump:’ First-Year Law School Enrollment Dipped in 2019,” December 12, 2019, Law.Com, https://www.law.com/2019/12/12/forget-the-trump-bump-law-school-enrollment-dipped-a-bit-in-2019/.

[3] Louis Toepfer, “Introduction,” in Seymour Warkov and Joseph Zelan, Lawyers in the Making (1965); at xv.

[4] Supra note 1 at 2.

[5] Id at 4.

[6] Id at 5.

[7] See supra note 1 at 6.

[8] Shih-Chun Chien & Stephen Daniels, “Who Wants to be a Prosecutor? and Why Care? Law Students’ Career Aspirations and Reform Prosecutors’ Goals,” Howard Law Journal (forthcoming 2022), using 2010 data to explore connections among motivations, preferred area of legal specialization, and preferred work setting upon graduation.

[9] The 2010 LSSSE survey asked students to choose from a list of 26 areas of legal specialization for their preferred area of specialization upon graduation.

[10] The analysis includes the issues of diversity and gender. One interesting finding is that African-American males interested in criminal law are more likely to eschew work as a prosecutor or as a public defender in favor of private practice. AAPI students are the least likely cohort to choose criminal law as their area of specialization.

[11] The Changing Landscape of Legal Education: A 15-Year LSSSE Retrospective (2020) at 9, https://lssse.indiana.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/LSSSE_Annual-Report_Winter2020_Final-2.pdf.

[12] We are particularly interested in whether the rise and proliferation of progressive prosecutors and other recent civil justice reform/Black Lives Matter-type movements and anti-Asian hate crimes affect law students’ motivations and career aspirations.

[13] Our earlier blog reported on 1Ls who rated each motivation in 2010 at 6-7 (the two highest ranks). Here Figure1 reports on respondents who rated each motivation at 5-7. This is consistent with the approach we used in supra note 9. It also allows us to accentuate the changing intensity for motivations.

Guest Post: Penalizing Preventative Mental Health Treatment for Law Students

Guest Post: Penalizing Preventative Mental Health Treatment for Law Students

Doron Dorfman

Associate Professor of Law

Syracuse University College of Law

The study of mental health of law students can be traced back to the late 1960s when research published in the Wisconsin Law Review found that “failure anxiety” has been a serious impediment for first-year law students’ ability to study. Research from the 1980s all the way to 2016 has shown that the stress and anxiety is not only a problem found among 1Ls, but also one that continues throughout the law school journey.

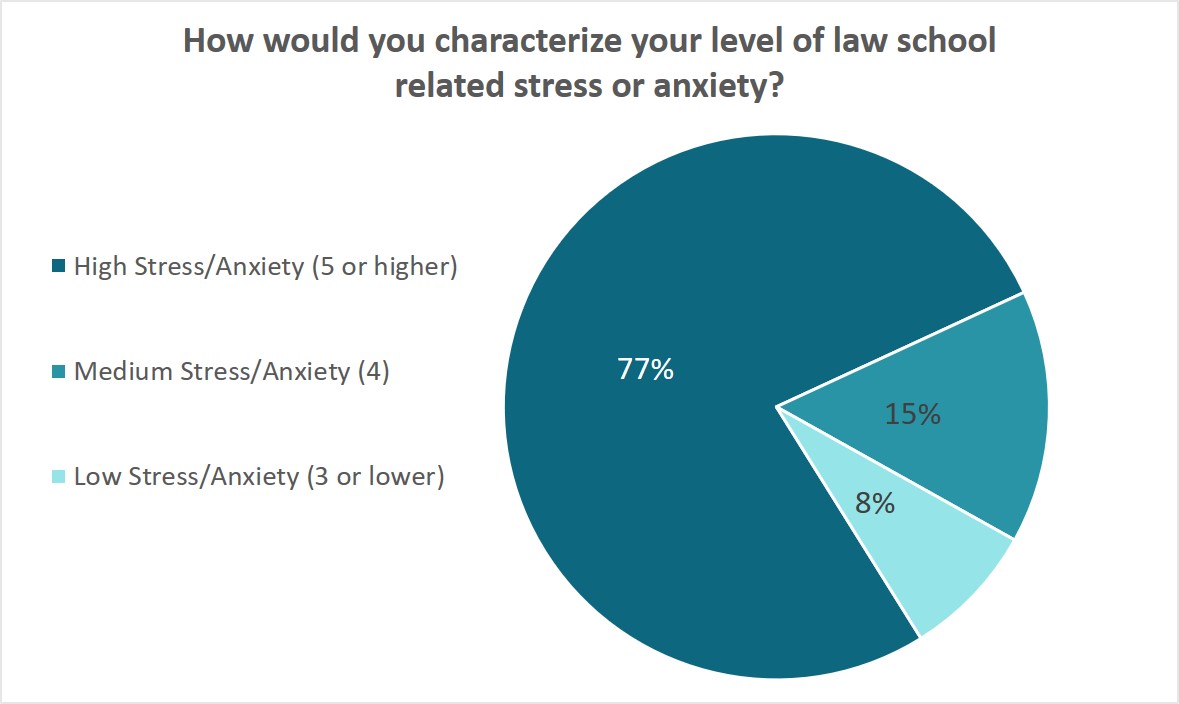

It has been known for decades that attending law school is an extremely stressful experience. As recent LSSSE data demonstrate, attending law school remains stressful and anxiety provoking. A 2020–21 LSSSE survey module based on a sample of more than 2,000 law students shows that 77% percent of the students surveyed found the level of stress and anxiety in law school to be a 5 or higher on a 7-point Likert scale.

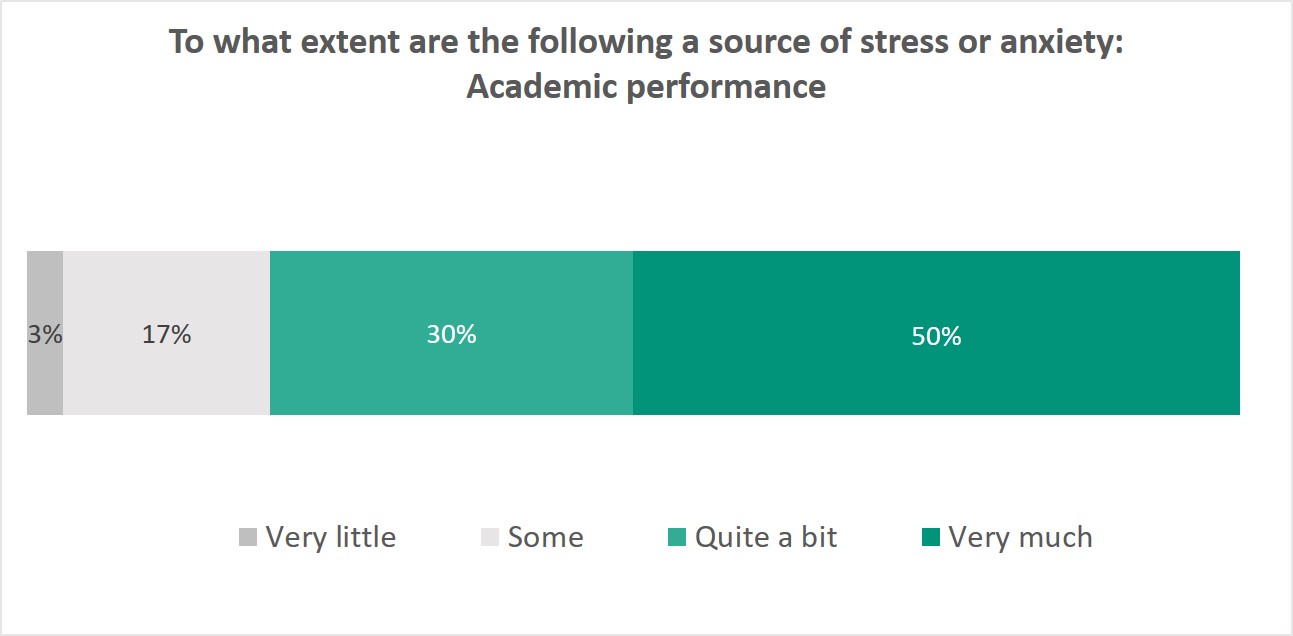

Much like the peers from 50 years ago, 50% of the sample say that the source of their stress or anxiety is “very much” due to concerns about academic performance.

In a new research project, I examine what I call the “the paradoxical legal treatment of preventative medicine” showing how while the law on the books, specifically the Affordable Care Act, contains avenues to promote and encourage preventive medicine, those efforts clash with other policies and decision-making processes that in action penalize those who take preventative measures. This contradiction creates a chilling effect on those trying to take preventative health measures and impedes the ACA’s original goal of promoting this important tool to foster the quality of health care.

One of the examples of this phenomenon is the Character and Fitness evaluations state bar associations conduct around the country, used to admit prospective lawyers into the bar. These evaluations take into account the students’ mental health history. In a 2016 study, it was found that the number one reason for students not seeking mental health treatment, which can be classified as “secondary prevention,” one that is practiced after the illness has been diagnosed but before it has become symptomatic, is the potential threat to bar admission.

As one law student recently acknowledged, he refused to seek out mental health resources when law school stress was becoming too much, as he did not want to risk being flagged during the state bar’s Character and Fitness evaluation. Instead, he developed a drinking habit to relieve his stress.

As I trace in my new work-in-progress over the last 30 years since its enactment, the Americans with Disabilities Act limited the inquiries state bar associations can make in regard to a candidate’s past mental health treatments. Some courts have also adopted a behavioral approach, whereby prior mental health treatments, and even current counseling, do not in and of themselves deem a person unfit to practice law if no present behavioral issues exist. Yet the problem of penalizing preventative mental health treatment in the context of state bars’ character and fitness evaluations persists in other states as indicated by a 2019 report by the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law.

Updated data on the mental health of law students, such as those collected by the LSSSE, are crucial for continuing the efforts to stop penalizing those seeking professional help for their stress and anxieties during law school. As I show in my work, it is another important arena in which the need to make sure the law promotes preventative medicine is particularly acute.

Ensuring that all state bars across the country find ways to balance the need to ensure applicants’ qualifications as competency and good moral character without penalizing and stigmatizing mental health treatment is a crucial goal that also holds the promise of diversifying the legal profession.

How Hard Do Law Students Work Outside of Class?

The average law student spends a sizeable amount of time reading and otherwise preparing for class each week. But given the stresses and time pressures placed up students, how many of them occasionally skip the required readings? We examined LSSSE data from 2004 to present to look for trends.

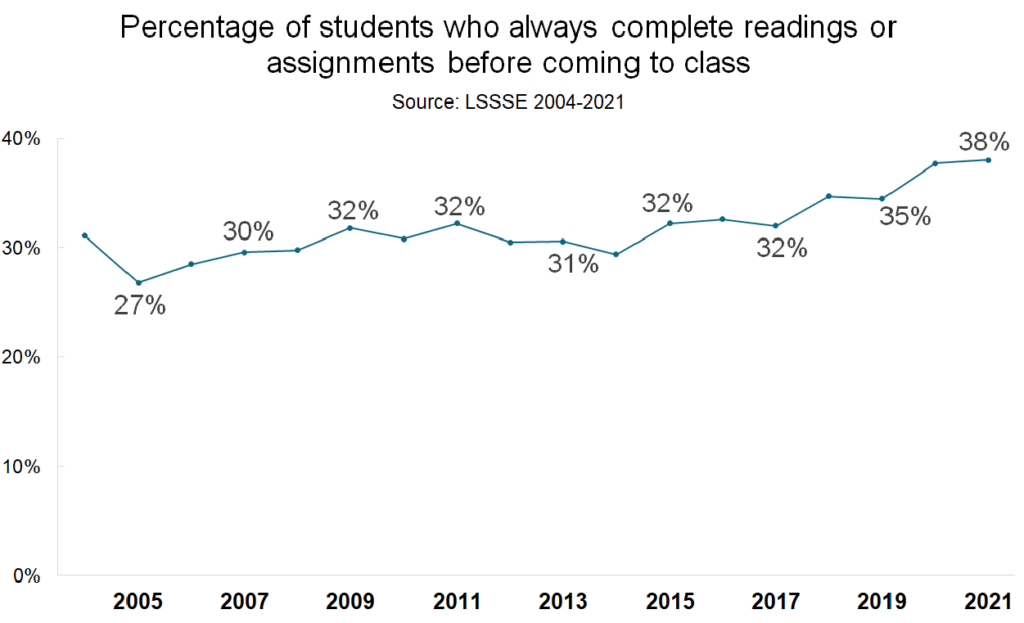

LSSSE’s core survey asks about how often students come to class without completing required readings or assignments. In 2021, fully 38% of students said they never came to class unprepared. This is up significantly from the all-time low in 2005 of only 27% who said they always completed required readings and assignments. In fact, there has been a steady upward trend toward meticulous class preparation over the last decade and a half.

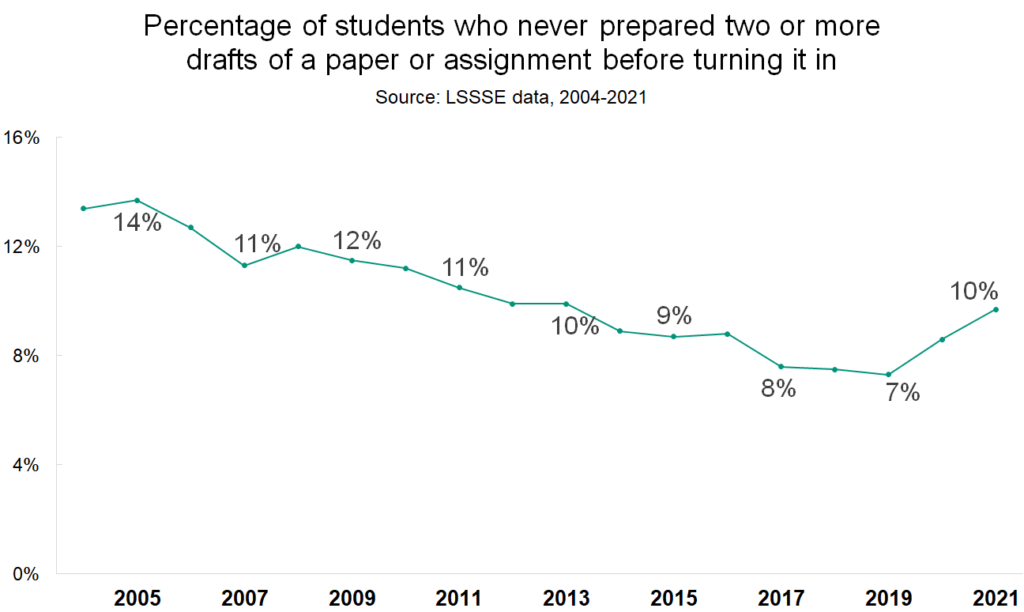

A similar attitude toward hard work outside of class time can be seen in the percentage of students who prepare multiple drafts of a paper or assignment before turning it in. In 2005, 14% of student never prepared additional drafts of their coursework. By 2019, that number had dropped to 7%. However, in 2020 and 2021, the number of students who never prepared multiple drafts increased slightly again. It will be interesting to see whether this is a pandemic-fatigue effect or whether students are gradually showing either less interest in re-writing or less available time in which to do so.

Writing can play an important role in developing critical thinking and reasoning skills, which is why it is a central component to a legal education. This is also true of doing assigned reading, which occupies about 18.5 hours of a law student’s week on average, and performing other types of course preparation, which takes another 11.2 hours of effort per week. Since LSSSE started collecting data in 2004, it appears that law students have generally become more engaged with putting in the effort necessary to reap the benefits of a legal education, even when that effort happens at home.

Guest Post: How Sending One E-mail a Week Helped Me Connect Better to My Law Students

Guest Post: How Sending One E-mail a Week Helped Me Connect Better to My Law Students

Jonah E. Perlin

Associate Professor of Law, Legal Practice

Georgetown Law School

Building connections with our students is one of the most valuable things we can do as law professors. Not only do these connections help us become stronger teachers, connection is also integral to our students’ success. As LSSSE’s “2018 Relationships Matter Survey” explained, “Law students who build strong connect ions with faculty, administrators, and classmates are more likely to appreciate their legal education overall and also have better academic and professional outcomes.”

But during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic when many law school courses including my own moved from the physical classroom to the digital world it became more challenging to create these connections. Gone were the informal chats in the hallway before and after class. Gone were the opportunities for a student to just “stop by” my office. Gone were the chance meetings in the cafeteria. Gone were so many of those regular but informal moments that help transform professor-student relationships from transactional to personal.

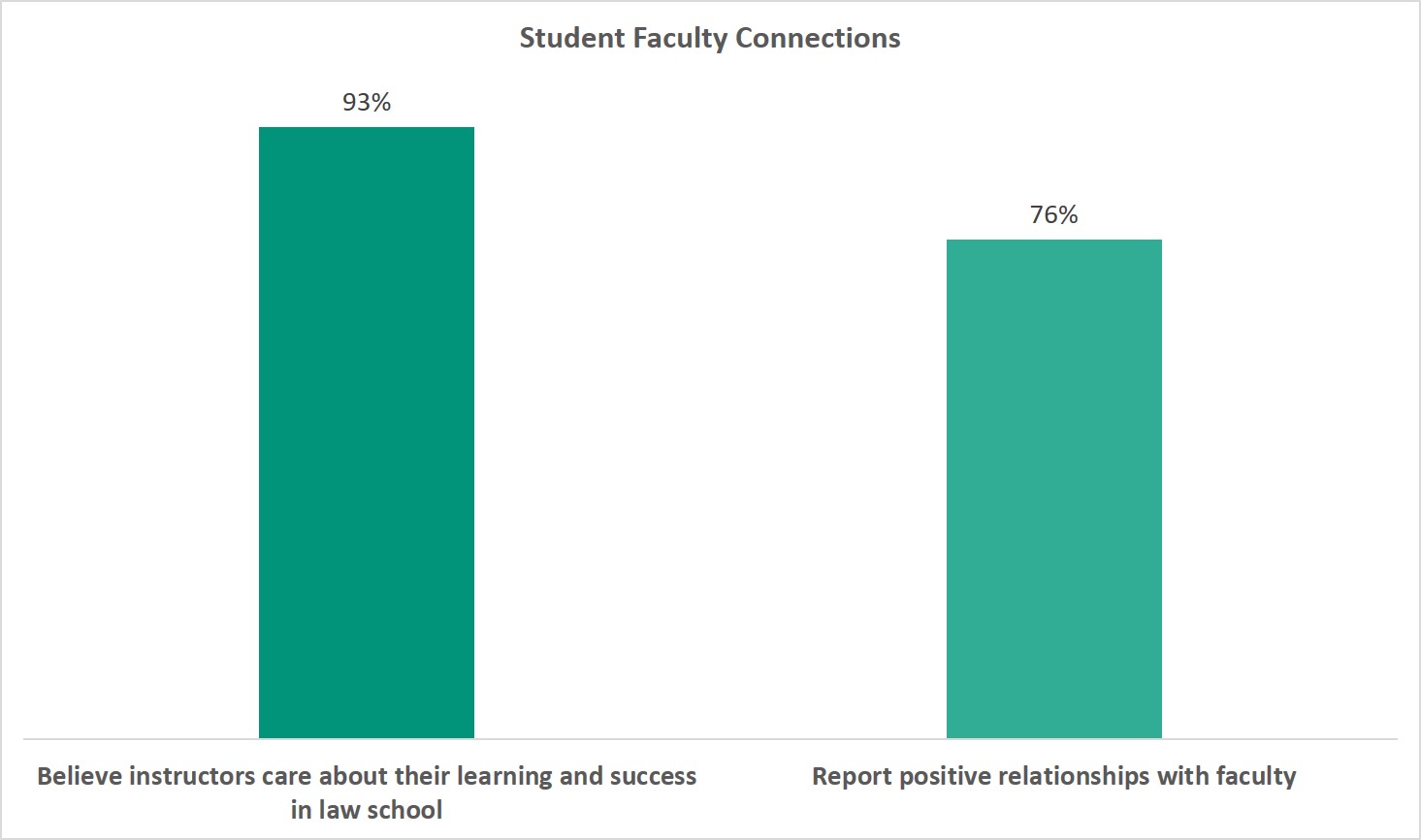

As the “Relationship Matters Survey” also reports a staggering 93% of law students believe that their instructors care about their learning and success in law school but the new reality required new pedagogical techniques to maintain this level of connection.

During the three semesters that I taught remotely, I tried several techniques to build this deeper personal connections with individual students and with my class as a whole. Some worked. Some didn’t. But what surprised me was that the single most successful tool to build connections with students in my first year course--and one which I continue to use even now that I have returned to teaching in-person--is sending a weekly takeaway e-mail.

Yes, you read that right. Writing one takeaway e-mail every Friday to my students has significantly improved my teaching and more specifically my connection to my students.

The Power of Takeaway E-mails

At first glance the proposal to send a weekly takeaway e-mail to law school students might seem at best unnecessary and at worst patronizing. After all, students in professional schools should be responsible for keeping up with class, completing their assignments on time, and identifying where they do not understand the material or need further assistance. More than that, receiving a newsletter-style weekly e-mail is a technique that many associate with elementary school teachers and local clubs or organizations.

Yet, as a consumer of remote, cohort-based online courses myself, I was surprised to learn that takeaway e-mails were common in online learning environments. These e-mails sent at the completion of class clarified what had been covered, previewed what was to come, and most of all gave me the sense that the instructors cared about my learning process. More than that, these e-mails felt like a free bonus class session that I could complete on my own time. From this experience as a consumer of online education, I decided that these asynchronous touch points would work just as well in my first-year Legal Practice course.

Now, after more than a year of sending weekly takeaway e-mails to my 1L students, I can say with confidence that takeaway e-mails make me a better teacher and, more importantly, help me build greater personal connection with my students for several reasons:

- More Regular Interaction. Students in my class have come to expect the e-mails and refer to them as they would class time. It is a fast, low effort, high impact way of connecting with students three times a week instead of only twice.

- Different Medium. Unlike classroom sessions which are largely conducted orally, the takeaway e-mail allows me to communicate with my students in a different mode of communication, the written word. It is often easier to articulate in writing lessons not just about the products I am asking them to create but also about the process of learning how to create those products. This helps students focus on the metaskills law school seeks to teach them: how to learn, how to deal with new tasks, and how to handle new problems that need to be solved.

- Bigger Picture. The e-mail is a chance to contextualize and crystallize the content covered the prior week and how it fits into the larger trajectory of the course and what is to come. In my experience, students who see this bigger picture earlier are often more successful in the course.

- Less Administrative E-mail. Takeaway e-mails allow me to handle 99% of the administrative and logistical issues that used to consume so much of my time. Instead of receiving and responding to lots of one-off e-mails that get lost in the shuffle, the weekly e-mail provides a one-stop, centralized, and easy-to-find place for reminding students as a class of what we’ve done and what is to come.

- Personal Connection. These e-mails allow me to further connect to students on a personal level. In them I can tell my students what I am working on, why I assigned a certain piece of reading, or even about activities that I am looking forward to on the law school campus. It adds a human touch sometimes hard to convey from the front of a classroom.

- Shorten the Feedback Cycle. If I learn after class that there is a common question or point of confusion based on office hours or individual student meetings, I am able to easily address that question in the weekly e-mail before the weekend begins so that we can start the next session without needing to go backwards.

I have learned from experience that a weekly takeaway e-mail is not only not patronizing to our students, it instead treats them like professional adults and with respect. Instead of sending one-off e-mails whenever I think of something I might want to share, they now look for one e-mail a week with exactly what they need. This allows me to model professional behavior while keeping my students apprised of key information that they need to know in a predictable and concise fashion.

What My Weekly E-mail Looks Like

An effective weekly takeaway e-mail can use any format. That said, the two keys to success in my view are (1) consistent organization and (2) consistent timing. These touchstones allow for takeaway e-mails that are more easy to create and more easy to consume. I personally use our Learning Management System (Canvas) to send the takeaway e-mail as an “Announcement” so that it is sent by e-mail but also stored on the class home page and can be viewed at any time. Each week my e-mail begins with a statement about where the students are in the course (and in their first-year education). This adds context to the educational moment on their journey. It then includes a brief recap of each class meeting in the prior week and a section on the deadlines and topics that will be covered in the week to come. Then it contains additional sections, as needed, about substantive areas that we covered in class, answers to frequently asked questions, or information about exciting events on campus or articles that I want to draw their attention to. To make it easy to read on mobile devices I use section headings with content-relevant emojis so it is easy to skim (for example, ✅ Assignments). And the best part of all is that because the flow of my course is similar year-to-year, large parts of the e-mail can be reused in future years helping leverage that initial investment of time in my future teaching.

But Really? E-mail.

Yes. For better or worse we live in a society in which information is conveyed by e-mail. One benefit is that we can build connections by e-mail that we are unable to build in limited in-person experiences--and those connections can be built asynchronously and from our own homes. We can use this tool as professors in a way that inspires deeper connection and models professional behavior as opposed to a tool that creates a constant stream of ad hoc information. In less than 30 minutes a week, this one technique has allowed me to build deeper connections with my students, spend less time responding to individual questions, and model a culture of learning and accountability in my classroom.

The Changing Landscape of Legal Education: High Levels of Satisfaction

In spite of many challenges, law students report relatively constant positive levels of satisfaction with legal education over the last decade and a half. Our 2020 special report The Changing Landscape of Legal Education: A 15-Year LSSSE Retrospective shares longitudinal findings on select metrics as well as demographic differences within variables to catalog how legal education has changed over time. In this blog post, we highlight the remarkably high levels of satisfaction that students have expressed about their law school experience since LSSSE’s inception.

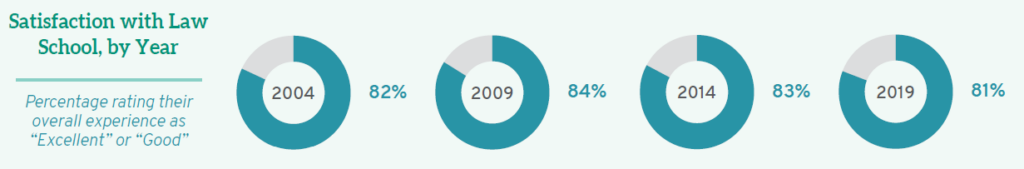

When students were asked, “How would you evaluate your entire educational experience at your law school?” over eighty percent of all law students rated their experience as at least “good” with roughly one-third of all students saying they have enjoyed an “excellent” law school experience.

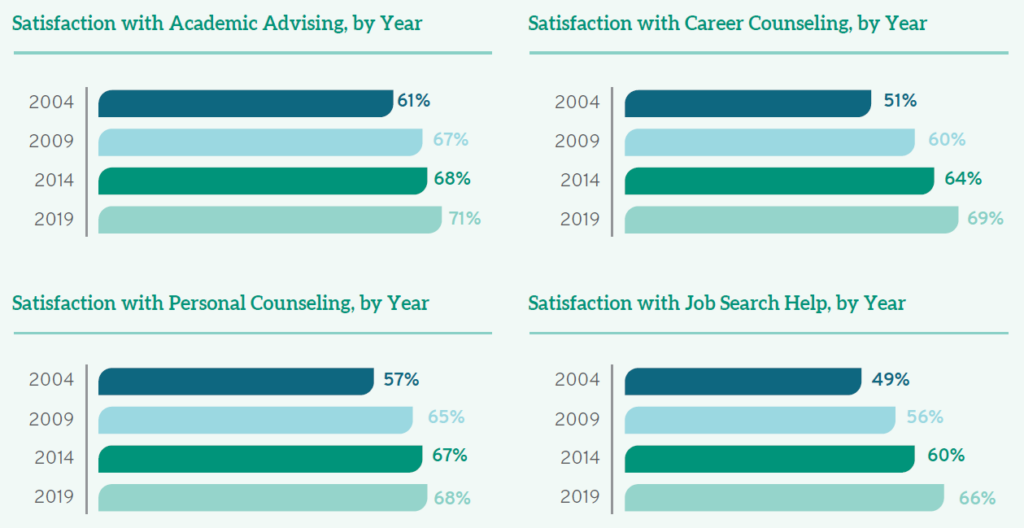

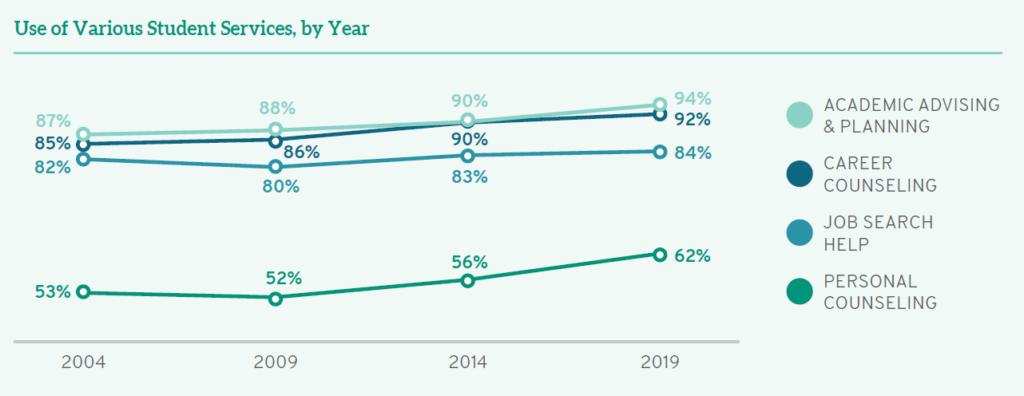

If we consider student satisfaction with a number of different encounters—including academic advising, career counseling, personal counseling, and job search help—we see a consistent pattern of improvement over fifteen years. While over half (53%) of students who sought out academic support were “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with advising and planning in 2004, that number grew to almost three quarters (71%) of all students by 2019. Interestingly, there are also more students using academic advising and planning today than in years past: a full 94% of students used those services last year.

Students also appreciate how the significant investment of career counselors improves their professional prospects. While fifteen years ago, 51% of students were satisfied with career counseling (and 9.9% of these were “very satisfied), satisfaction has grown steadily over time with 60% satisfied in 2009, 64% in 2014, and a remarkable 69% satisfied in 2019 (with 22% of those noting they are “very satisfied”). As with academic advising, higher percentages of students are taking advantage of career counseling—only 8.0% of students in 2019 did not use this service (compared to 15% in 2004).

The vast majority of students sought assistance with the job search in 2004 and in subsequent years. While almost half (49%) of students were satisfied with staff efforts to provide job search help in 2004, those numbers have increased over time to 56% in 2009, 60% in 2014, and now to 66%. Although there is room for improvement, students are noticing and appreciating improvement over time.

The Changing Landscape of Legal Education: Positive Learning Outcomes

Over the past fifteen years, LSSSE has documented dramatic changes in legal education. From 2004 to 2019, the changing landscape of law school was punctuated by increasing diversity among students, rising debt levels, relative consistency in job expectations, and improvements in various learning outcomes. In spite of many challenges, law students nevertheless report relatively constant positive levels of satisfaction with legal education overall. Our 2020 special report The Changing Landscape of Legal Education: A 15-Year LSSSE Retrospective shares longitudinal findings on select metrics as well as demographic differences within variables to catalog how legal education has changed over time. In this blog post, we will share how students have increased their achievement of selected learning outcomes from 2004 to 2019.

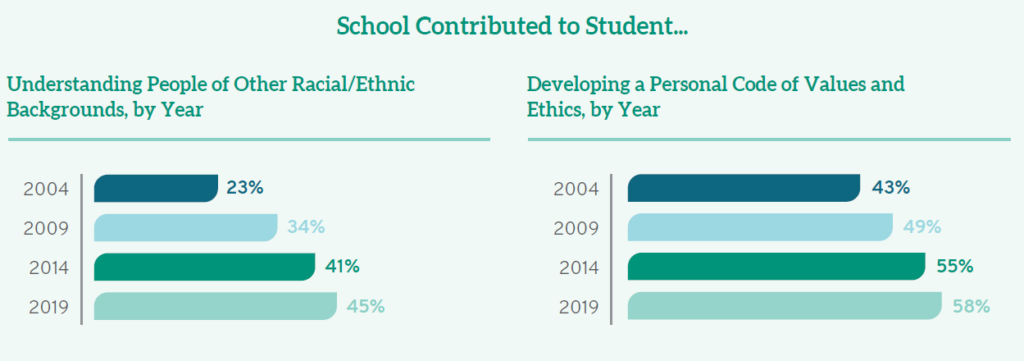

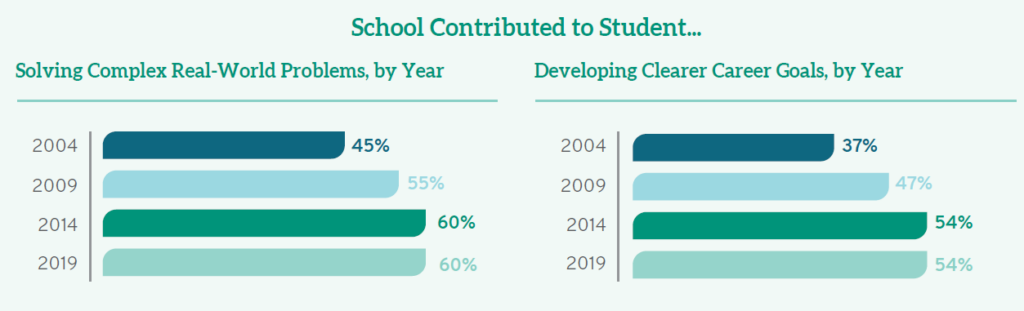

According to LSSSE data, law schools contributed to increases in a variety of perceived learning outcomes from 2004 to 2019; collectively, these point toward progress in terms of how students measure their own skills and likely in terms of actual practice-readiness of graduates. In 2004, only 23% of students saw their schools as doing “quite a bit” or “very much” to help them understand people of other racial and ethnic backgrounds; because of steady increases over the next fifteen years, especially between 2009 and 2014, almost half (45%) of students today see their schools as doing “quite a bit” or “very much” to prepare them to interact with racially diverse colleagues and clients.

In addition, schools have increased their emphasis on professional responsibility in the past fifteen years. While even in 2004 a full 43% of students saw their schools as doing “quite a bit” or “very much” to encourage them to develop a personal code of values and ethics, that number has now grown to 58%. Schools were already prioritizing complex problem solving fifteen years ago, and students see institutional support for this skill growing over time as well. While in 2004, 12% of students believed their law schools contributed “very much” to their ability to solve “complex real-world problems,” that percentage has doubled over fifteen years so that now almost a quarter (24%) of students agree. Law schools are also encouraging students to focus on developing career goals and aspirations. In 2004, almost a quarter (23%) of all law students saw their schools doing “very little” to contribute to their developing clearer career goals; by 2019 those statistics dropped to 14%. On the flip side, while only 11% saw their schools doing “very much” in this regard in 2004, that number has risen steadily, reaching 22% in 2014 and remaining there in 2019.

Looking at the past can help prepare us for our future. To learn more, you can read the entire Changing Landscape report here.

Guest Post: Student Response Systems as a Tool for Formative Assessment

Guest Post: Student Response Systems as a Tool for Formative Assessment

Hannah Haksgaard

Associate Professor

University of South Dakota Knudson School of Law

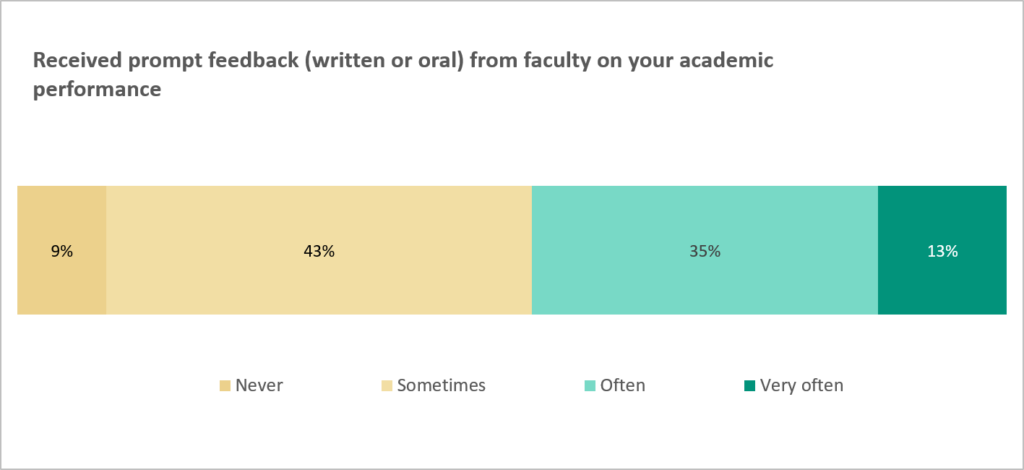

Under American Bar Association Standard 314, law schools—and therefore individual law professors—are required to engage in formative and summative assessment of students. Formative assessment is assessment that occurs during the semester where students receive feedback in order to improve their performance. Although formative assessments do not need to be graded, formative assessments must include feedback that is detailed and on point. Feedback on formative assessments is most valuable if it can be provided promptly. Yet, under half of the LSSSE respondents report receiving prompt feedback from faculty “often” or “very often” on academic performance.

However, this student response may be undercounting formative assessments. Professors give immediate feedback in all sorts of ways that students might not recognize, such as through a Socractic dialogue in class, through brief conversations in hallways, and through feedback on group discussions during class. More formal feedback—such as graded quizzes or written comments on drafts or practice exams—is time-intensive for professors and can be especially burdensome for professors with large-enrollment courses or high service loads.

One way to provide fast feedback on student performance is to use student response systems in the classroom. Traditionally operated through hand-held clickers, student response systems are now internet-based programs that allow professors to pose multiple-choice or true/false questions on the screen and students to answer those questions on their phones or computers. Programs include Kahoot!, Mentimeter, Poll Everywhere, Socrative, Turning, and many others.

Importantly, these programs provide immediate feedback to students. Once all of the students have answered a question, the correct answer is highlighted on the screen. Plus, each student’s own device tells the student whether they were right or wrong on that question. In addition to providing feedback to students about their own individual performance, these programs show what percentage of the class chose each answer. This allows students to recognize how they are performing in comparison to peers and allows professors to modify their teaching based on the responses received.

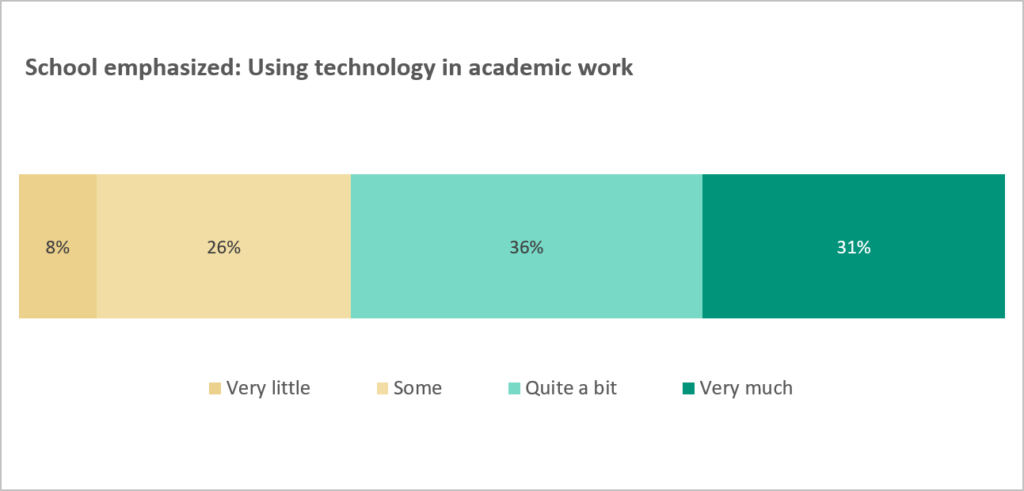

During the COVID-19 pandemic, law professors and law students have been forced to adopt more technology in teaching and learning. Student response systems are an important way to leverage technology whether for in-person, hyflex, or online teaching. According to the LSSSE, most students feel their schools emphasize using technology in academic work.

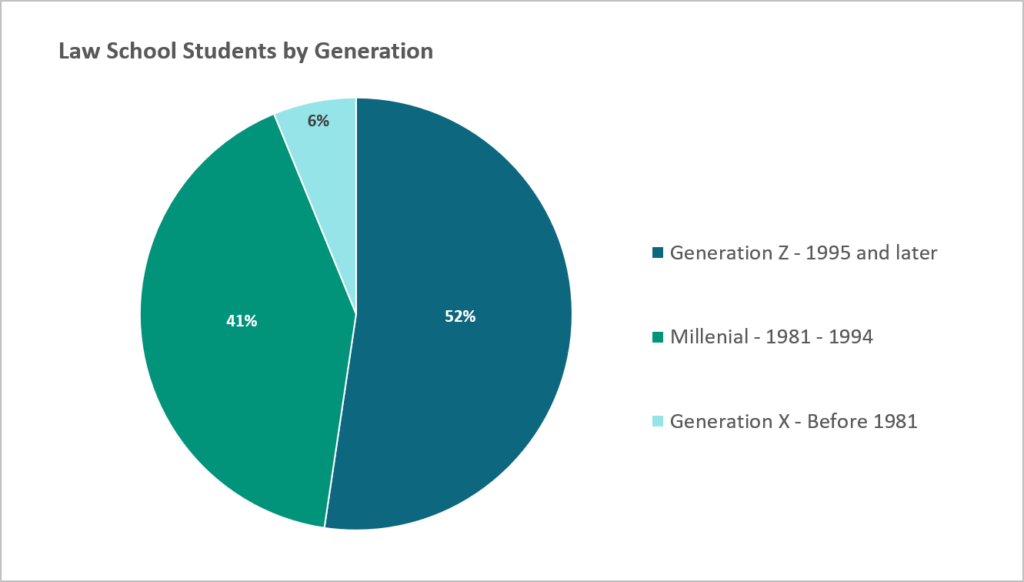

Student response systems are a way to emphasize the use of technology in the actual classroom in order to improve student learning and student participation. This is particularly important for Generation Z law students—those born between 1995 and 2010—who already make up a majority of law students, having now replaced millennials as the dominant generation in law school.

Research shows that Generation Z students expect to receive information quickly and have trouble disconnecting from cell phones.[1] Using those cell phones for in-class activities through student response systems can both engage law students and provide them the immediate feedback they seek.

This technology will never replace substantive written feedback or one-on-one meetings to discuss assignments, but student response systems are a way to supplement other assignments and types of feedback. Both students and professors benefit from formative assessment, and student response systems are an easy way to provide the immediate feedback that students need.

__

[1] Tiffany D. Atkins, #ForTheCulture: Generation Z and the Future of Legal Education, 26 Mich. J. Race & L. 115, 135 (2020).

Guest Post: A Message to White Law Faculty: Mentor Racial Minority Students

Guest Post: A Message to White Law Faculty: Mentor Racial Minority Students

Guest Post: A Message to White Law Faculty: Mentor Racial Minority Students

Gregory S. Parks

Associate Dean of Strategic Initiatives and Professor of Law

Wake Forest University School of Law

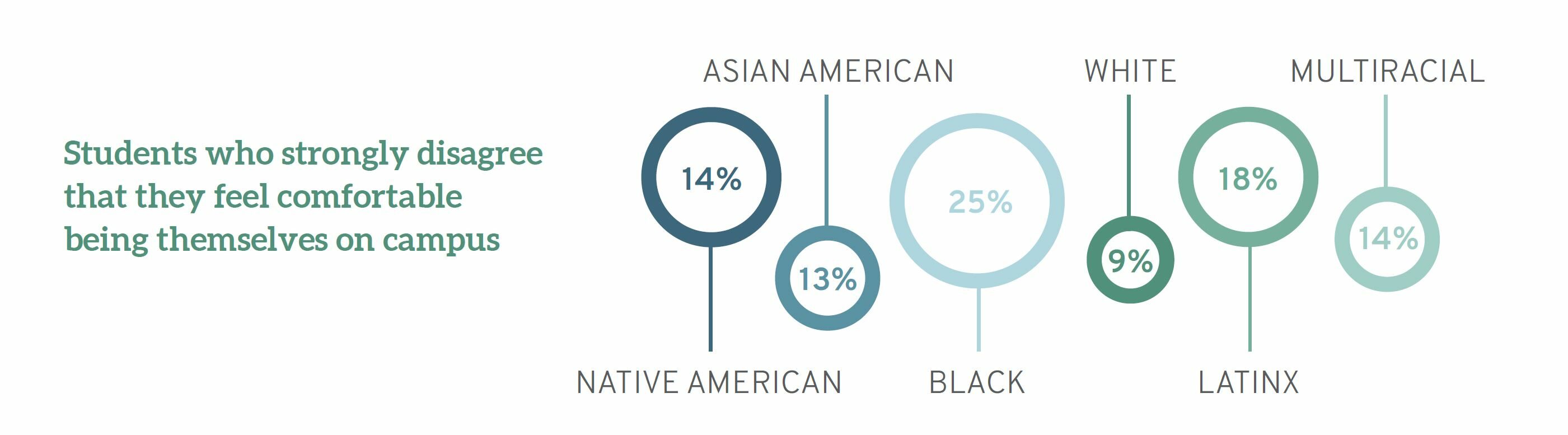

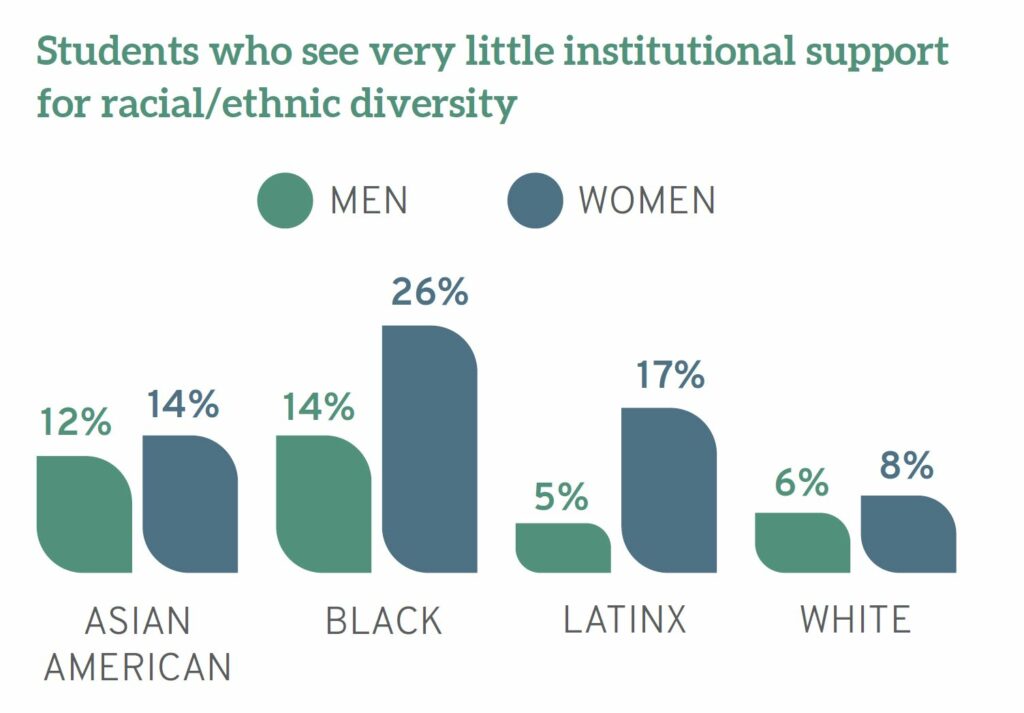

Pursuant to Law School Survey of Student Engagement’s (“LSSSE”) 2020 Diversity and Exclusion Annual Survey, there are troubling findings with regard to racial minority students’ sense of belonging and institutional support. Thirty-one percent of White students, but only 21% of Black and Native American students, feel a part of their law school community. Moreover, “women of color are more likely than men from same ethnic/racial backgrounds to feel that they are not part of the campus community.” Specifically, 34% of Black women law students felt this way. When asked if they did not feel comfortable being themselves on campus, 12% of White students agreed compared to 21% of Black, Latinx, and Native American students. Students of color are more likely to believe that their school does “very little” to ensure they are not stigmatized based on identity characteristics. Twenty-five percent of Black, 18% of Latinx, and 14% of Native American students—compared to 9% of White students—agree with the statement.

When it comes to perceptions of institutional support, 32% of White students believe that their school does “very much” to support diversity compared to 18% of Black students. Correspondingly, 26% of Black women, 14% of Black men, 8% of White women, and 6% of White men believe that their school is doing “very little” to create an environment to support diversity. In addition, 28% of White students feel like their school does “very much” to support community among students while 18% of Black students and 14% of Latinx think their school does “very little.” Not surprisingly, only 31% of Black men, 18% of Black women, 32% of Latinx men, 23% of Latinx women, 31% of White men, 26% of White women, 25% of Asian American men, 23% of Asian American women, 27% multi-racial men, and 23% multi-racial women strongly agree that they feel valued by their institution.

Faculty of color often shoulder a disproportionate amount of emotional labor in supporting students of color.[1] As such, White law faculty can and should play a meaningful role in making the law school experience one where racial minority law students feel a greater sense of belonging and institutional support. That is through mentoring. Mentoring has two distinct functions—professional and psychological. Professional mentoring aids the mentee in advancing in the workplace. Psychological mentoring seeks to bolster the mentee’s competence, effectiveness, and identity. Mentoring relationships are rooted in clear expectations, mutual respect, personal connection, reciprocity, and shared values. Within the context of cross-racial mentoring relationships, mentors must be proactive in building a foundation of mutual respect and trust. In doing so, the mentor must develop cultural awareness and sensitivity to cross-cultural issues.

As such, mentors must:

- Recognize their own privilege.

- Have a growth-mindset in the relationship.

- Empathize with their mentee where possible.

- Listen to understand when they cannot.

- Guide the mentee to their own fullest potential.

- Diversify their own viewpoints and knowledge to become more informed on issues that may not affect them.

It takes work to be a good mentor. But it pays dividends for the mentee, mentor, institution, and legal profession. Law faculty have a lot on their plate. And while it is unreasonable to think that law faculty, in the aggregate, can mentor every law student at their school, the truth is that we can likely do much better than we are doing. And given that racial minority law faculty often carry much of the emotional labor associated with supporting the most marginalized law students, White colleges can and should play a much more significant role in this effort.

___

[1] See Meera E. Deo, Unequal Profession: Race and Gender in Legal Academia (2019)(note chapters 3 and 4).

Knowledge, Skills, and Personal Development in Law School

What does one learn in law school? In this post, we describe the areas of academic, professional, and personal development that graduating law students feel were most strongly influenced by their law school experience.

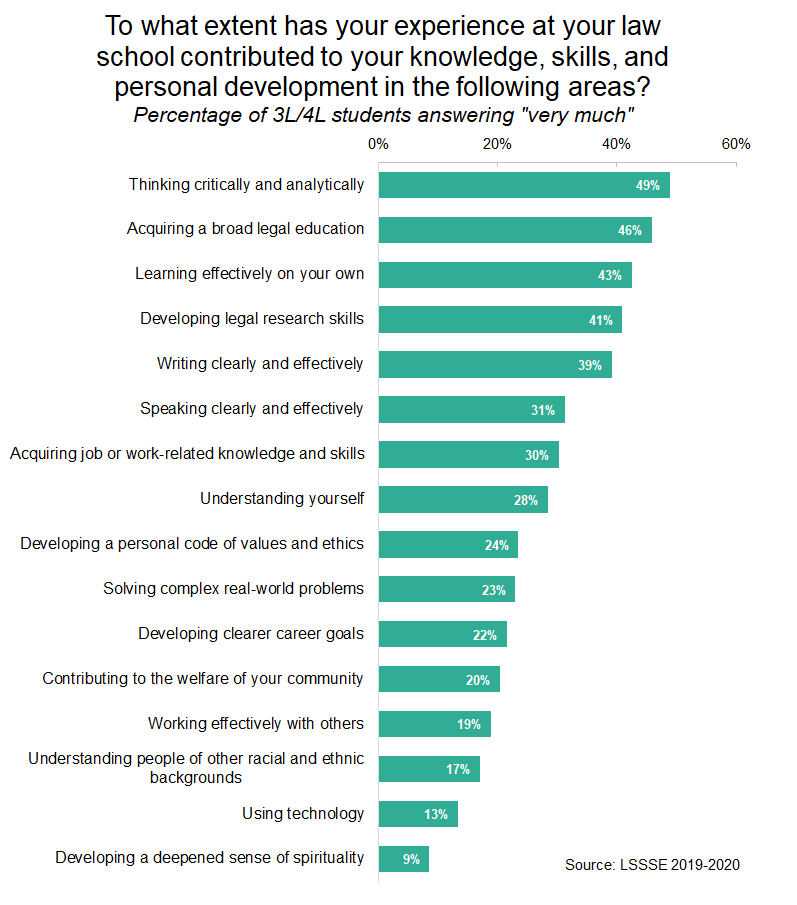

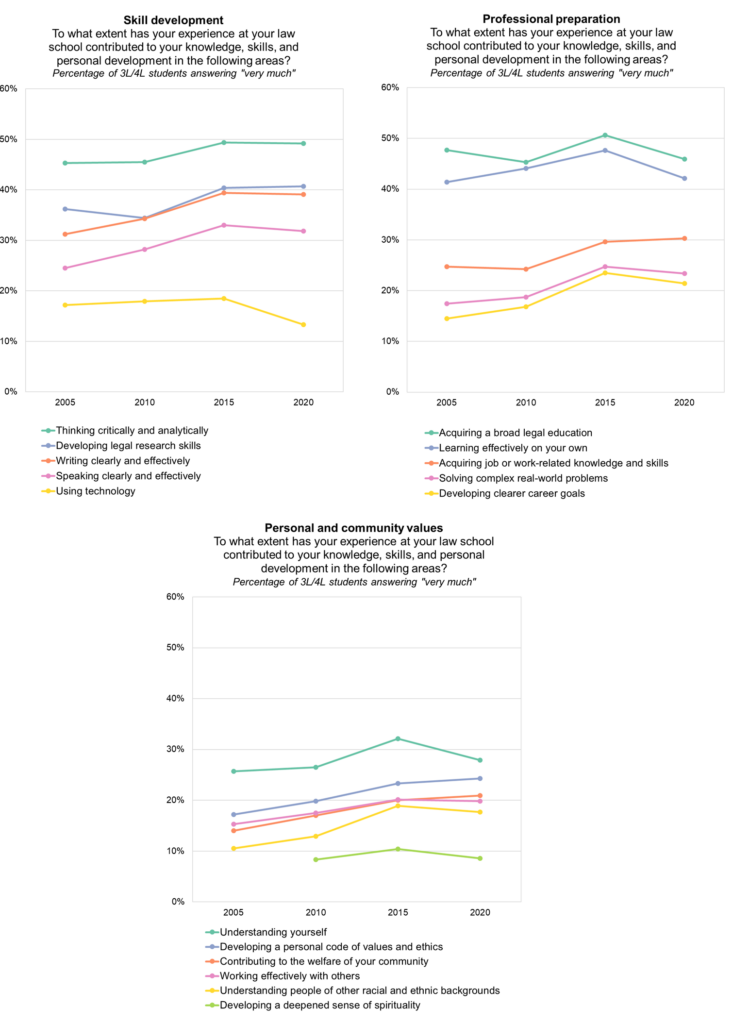

Students nearing graduation (full-time 3L students and part-time 4L students) in 2020 were most likely to say that they developed “very much” in terms of their ability to think critically and analytically (49%) and in acquiring a broad legal education (46%). Research, writing, and speaking skills were also key areas of academic and personal growth. Fewer students responded that they developed “very much” in interpersonal skills such as working effectively with others (19%) and understanding people who are different from themselves (17%).

From 2005 to the present, graduating law students have been remarkably consistent in the areas in which they say they have developed the most. Between 40% and 50% of law students over the last fifteen years feel they have acquired a broad legal education and learned how to learn effectively on their own. However, only around 20% of law students felt they had learned very much both about solving complex real-world problems and about developing clearer career goals, although these numbers have climbed over time. In terms of personal development and community values, usually about three in ten graduating students say they have made “very much” progress in understanding themselves, but only between 10% and 20% of students have made similar gains in understanding people of other racial and ethnic backgrounds. However, this area of interpersonal development has also increased noticeably over the last fifteen years.

Guest Post: Bridging Global Divides in Law School and Beyond

Guest Post: Bridging Global Divides in Law School and Beyond

Guest Post: Bridging Global Divides in Law School and Beyond

Shruti Rana

Professor International Law Practice

Assistant Dean of Curricular and Undergraduate Affairs

Director of the International Law and Institutions Program

Hamilton Lugar School of Global & International Studies

Indiana University Bloomington

International law is a growing and dynamic field, offering students a launching pad into a variety of careers spanning sectors from government to private practice to non-profit or advocacy work. Lawyers and advisors trained in international law have opportunities to address some of the most pressing global challenges of our time, and to build bridges through trade, business, migration, communications or capacity-building work. Careers in this field can be groundbreaking and even glamorous—notable international lawyers include Amal Clooney, Shirin Abadi, and Samantha Power.

Not surprisingly, then, international law is a popular choice for students entering law school—1L students rank international law as one of their top 10 areas of intended specialization. However, as they progress through law school, students’ interest in international careers drops steadily over time, and by graduation, international law drops down to sixteenth place in terms of student interest. These drops are especially striking for women and students of color, who initially show more interest in international law than other students yet appear similarly disillusioned by law school’s end. These trends are even more alarming for the legal profession and our nation as a whole when we consider that although “decades of research and experience prove that diversity strengthens decision-making, promotes innovation, and brings new, critical perspectives to global challenges,” women and people of color are greatly underrepresented in these global careers.

The Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) offers some intriguing data on the question of why U.S. law students turn away from international law over time. The data also provide clues as to where the key gaps in U.S. legal education are with respect to international law, and the impact of these gaps on students’ inclusion and opportunities in law school and beyond. They offer an important starting point for leaders in legal education to consider in developing programs and perspectives that cultivate and support students interested in careers in international law. Ultimately, addressing these gaps can help create more inclusive environments for all students, as well as foster the development of the global competency skills that are increasingly critical for any legal career.

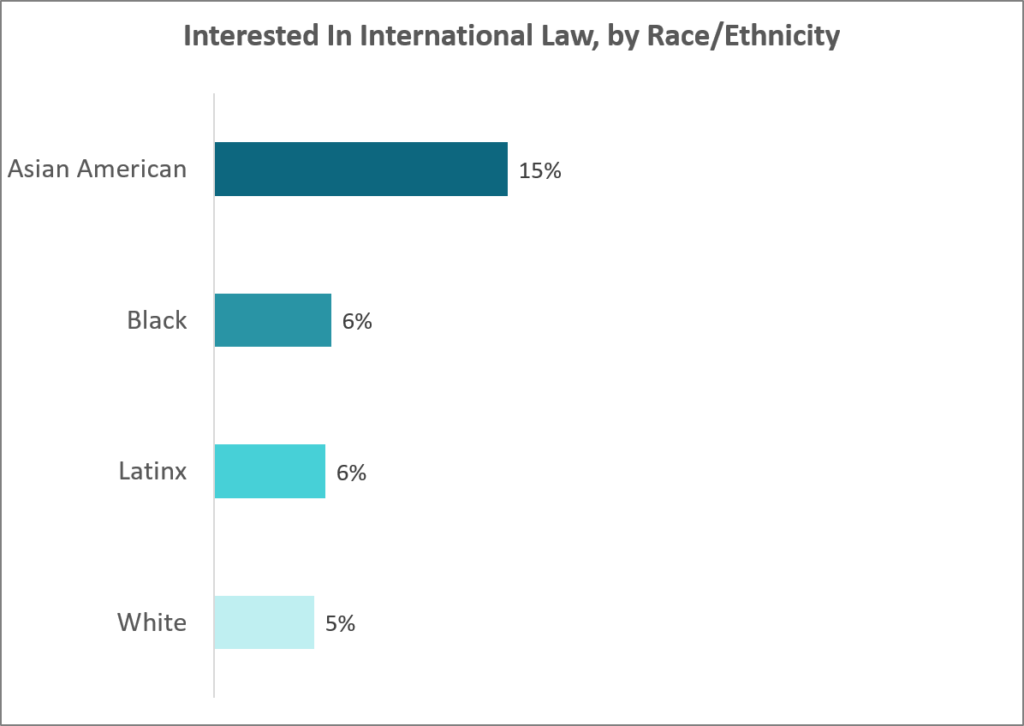

Beginning with the students themselves, LSSSE data show that students who express interest in and stick with international law as a career choice differ in striking ways from students who do neither. In terms of student diversity, there is a marked gender divide in interest in international law, with women comprising 64.8% of the students interested in pursuing international law. Overall, 7% of the women entering law school are interested in international law as compared to 5% of men. Students interested in international law are also more diverse in terms of race and ethnicity than students who are not, with Asian American students in particular significantly more interested in international law.

Students interested in international law are often advised to look outside of law school to develop the language, policymaking, and cultural competence skills they will need to understand the mechanisms of global governance and operate in diverse global environments. LSSSE’s data show that students interested in international law do just that. While in law school, students interested in international law are more than three times more likely to pursue a joint LLM or MA degree than students not interested in international law, perhaps to obtain global skills not traditionally taught in J.D. programs (34.8% of students interested in international law are pursuing a JD/MA, and 27.0% are pursuing a JD/LLM as opposed to 9.3% and 9.8%, respectively, of students not interested in international law). However, students who are interested in international law are about a third to one-half less likely than law students as a whole to pursue joint MBA or MS degrees. (13.5% of interested students pursue joint MBA degrees compared to 31.7% of non-interested students, and pursue MS degrees at roughly half the rate (4.5%) of students not interested in international law (8.1%). Perhaps because they must look elsewhere to develop the skills critical to international careers, students who express an interest in specializing in international law are also somewhat less satisfied with their law school experiences, as they are more likely to say that if they could start over again, they would probably not choose to attend the same law school they are now attending (18.6% of students interested in international law compared to 13.8% of students not interested in international law).

Looking beyond their law school experiences, students who express an interest in international law also show significantly different workplace preferences. As compared to students who do not express an interest in international law, they show a greater preference for government positions (15.6% vs. 10.5%), public interest groups (9.1% vs. 5.5%) and large firms over small (19.8% vs. 14.2%). They are also less interested in domestic criminal law (only 3.3% are interested working as prosecutors or public defenders, as compared to nearly 10% of students not interested in specializing in international law).

The differences delineated above correlate with and parallel larger trends in the fields of international law and global affairs. Although women make up an increasing percentage of students pursuing college and graduate education in law and the humanities, they are greatly underrepresented in professional careers in the international arena, where their perspectives and experiences are often devalued and marginalized. (See, e.g., Women in International Relations, Politics and Gender 4(1)(2008), and Do Women Matter to National Security? discussing survey results revealing the lack of women in leadership roles in these areas and in the priorities of these fields); see also The Emotional Labor of Teaching—A Feminist Critique of Teaching International Law discussing the marginalization of feminist perspectives in international law). It is likely that women both encounter these barriers to entry and general hostility to women in international affairs and institutions while in law school, and that these barriers are compounded by a lack of available mentors and visible representation in the field. The gendered impacts of these divisions are further amplified and mirrored when race, ethnicity, and the hierarchical and historical legacies of our current system of international law are added into the mix. The challenges of grappling with the colonial legacies of the current international order, or of addressing inequality through and within the field of international law, add to the already significant challenges of international careers.

It is likely that students begin (or continue) to encounter these perspectives and obstacles in law school, as international law and the language and cultural skills needed to pursue global careers are often marginalized within the legal academy. This marginalization is reflected in teaching and scholarship, the often negative perceptions of international LLM students in U.S. law schools (which LSSSE data has helped refute), and the contrasts with law schools outside of the U.S., where international law is usually a required subject. The international law arena is replete with the stories of people drawn to the field because of their experiences in the liminal, transformative spaces or social justice movements created in the wake of migration, development, war or the many other forms of global inequality—only to run directly into brick walls in law school when they encounter international law as “a discipline and a language that genuflects before the status quo” in ways that appear irreconcilable with goals such as addressing the causes and impacts of global inequality. Law schools, it appears, replicate rather than reduce the dynamics of inequality that first draw diverse students to law school, which then push them away from their careers of choice and the fields where diverse perspectives are so urgently needed.

The LSSSE data provide a valuable starting point for thinking about how we can continue to address the marginalization of international law in U.S. law schools, and its implications for students interested in international careers. We must support students in building global competency skills and the networks they need to break professional barriers, and foster an environment that equips them not to shackle but unleash the liberatory power of the law. At Indiana University, we have begun to take a number of innovative steps to address such obstacles, and create an inclusive environment focusing on the development of global skills to prepare students for careers in international law and global affairs. Our International Law and Institutions program, a joint endeavor between the Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies and the Maurer School of Law, focuses on the hard and soft skills students need to pursue careers in international law and global affairs. These programs include intensive language training combined with in-depth regional experience and a focus on gaining a holistic understanding of the tools and mechanisms of global governance and civic leadership. They also include initiatives aimed at enhancing the diversity of the field of global affairs and providing the mentorship, training and networks students need to succeed in these careers. As the global challenges we face intensify and multiply, these and other efforts to enhance and prioritize the skills and experiences our students need to be “globally ready” can help build the foundations for a more inclusive and equal future.