Success with Online Education: Relationships

The latest LSSSE Annual Results, Success with Online Education (pdf), focuses on the largely positive online learning experiment that law schools embarked upon due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This week and next week we will share selected snippets from the results. In this post we will describe how the switch to online learning impacted relationships among law students, law faculty, and administrators.

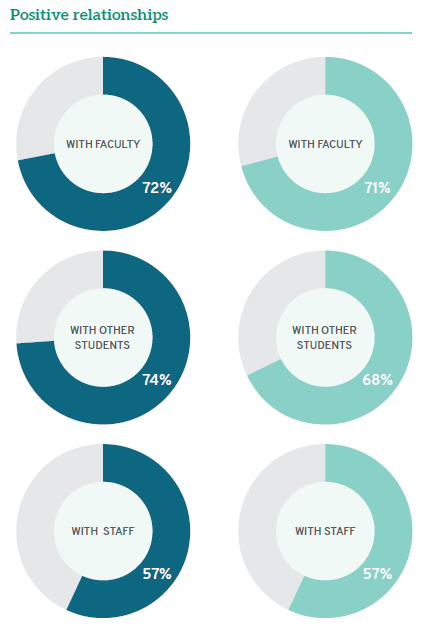

LSSSE data confirm other research showing how law school faculty have invested an enormous amount of energy and effort to connect with students, regardless of instructional modality. A full 72% of students taking mostly in-person classes have strong relationships with faculty (5 or higher on a 7-point scale), and 71% of mostly online students feel the same way. Students remain highly engaged with faculty in an online environment.

Online students and in-person students are equally likely to have positive relationships with administrative staff. A little over half (57%) of each group rate their relationships with their law school’s administrators a 5 or higher on a 7-point scale. Career services-oriented staff could consider using these relationships to bring more targeted career guidance to online students to narrow the gap in career preparedness between online students and in-person students. However, the relatively low percentage of both in-person and online students who have strong relationships with staff is a point of concern that should be addressed to better support law student development.

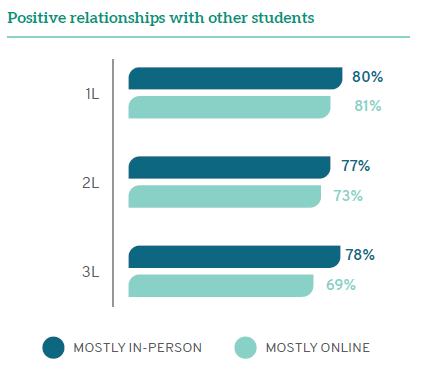

Despite similarly positive relationships with professors, students in mostly online classes are less likely than others to have strong relationships with each other. Only 68% of online students rate their relationships with their classmates positively, compared to nearly three-quarters (74%) of in-person students. There is again a disparity across class years, with 1Ls having similarly positive peer relationships regardless of mode of attendance and online 3Ls being much less likely to enjoy strong relationships with their peers than 3Ls attending in person. There may be a loss of social connections among online students because of a lack of the sort of incidental contact that builds relationships over time.

Next week we will discuss the learning experience in the virtual classroom. For the complete story, you can view the entire report on our website.

Guest Post: The Importance of Supporting First-Generation Law Students

Melissa A. Hale

Melissa A. Hale

Director of Learning for Legal Education

Law School Admission Council

Today is First-Generation Student Day[1]! So, to celebrate, I want to talk about why we should support first-generation law students, and how we can do that.

Who are first-gen students? Although definitions vary and self-identification is important, a first-generation student is typically one whose parents or legal guardians have not completed bachelor’s degrees [2]. First-generation students are an important part of diversity, equity, and inclusion. However these students are often overlooked when discussing DEI goals. In fact, when I started law school[3], I’m not even sure the term “first-generation student” was being used, or if it was in some circles, students certainly weren’t recognizing the term or identifying as “first-gen” the way they are now.

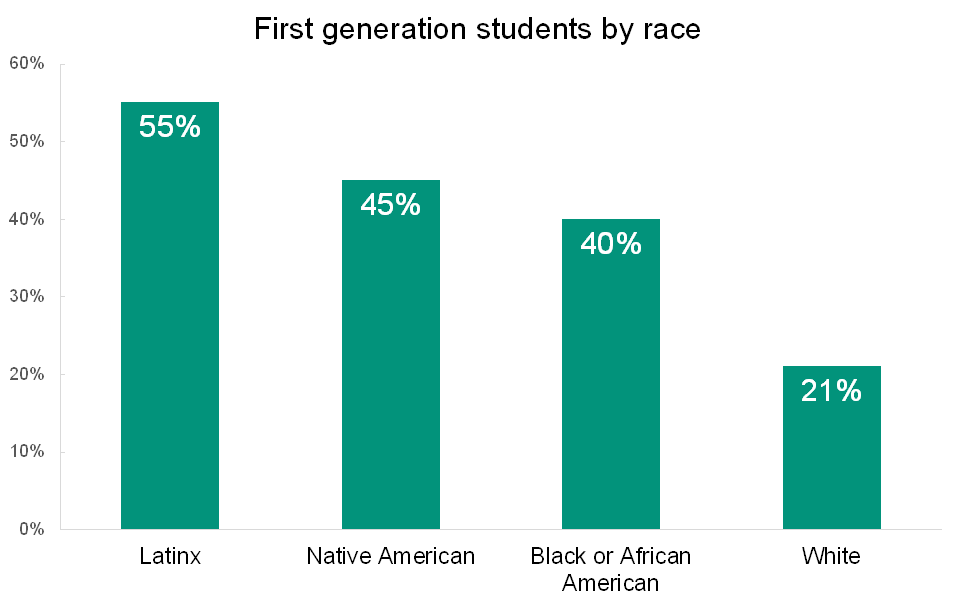

It’s certainly progress that we, as educators and researchers, are recognizing this group of students, but that’s not enough. We need to do more. Especially because there is significant intersectionality between first-generation students and historically underrepresented BIPOC students, including students of color and students from a lower socioeconomic status. According to the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE), 29% of law students are first-generation. Students of color are more likely than their white classmates to be first-generation. More than half of all Latinx students, 45% of Native American students, and 40% of Black or African American students are first-generation.

What Makes First-Generation Students Different?

So why does this matter and why is this group different? Well, first-generation law students often come to law school with fewer resources than their peers, including a lack of social capital. Most importantly, they also come to law school bearing an “achievement gap.” The “achievement gap” refers to the disparity in academic performance – grades, standardized-test scores, dropout rates, college-completion rates, even course selection and long-term success– between groups of students. In this instance, we are referring to the gap between students who have had parents complete some form of higher education (“continuing-generation students”) and those that have not. The Close the Gap Foundation refers to this as “the opportunity gap” instead of the achievement gap, and specifically states that it is “the way that uncontrollable life factors like race, language, economic, and family situations can contribute to lower rates of success in educational achievement, career prospects, and other life aspirations.”[4]

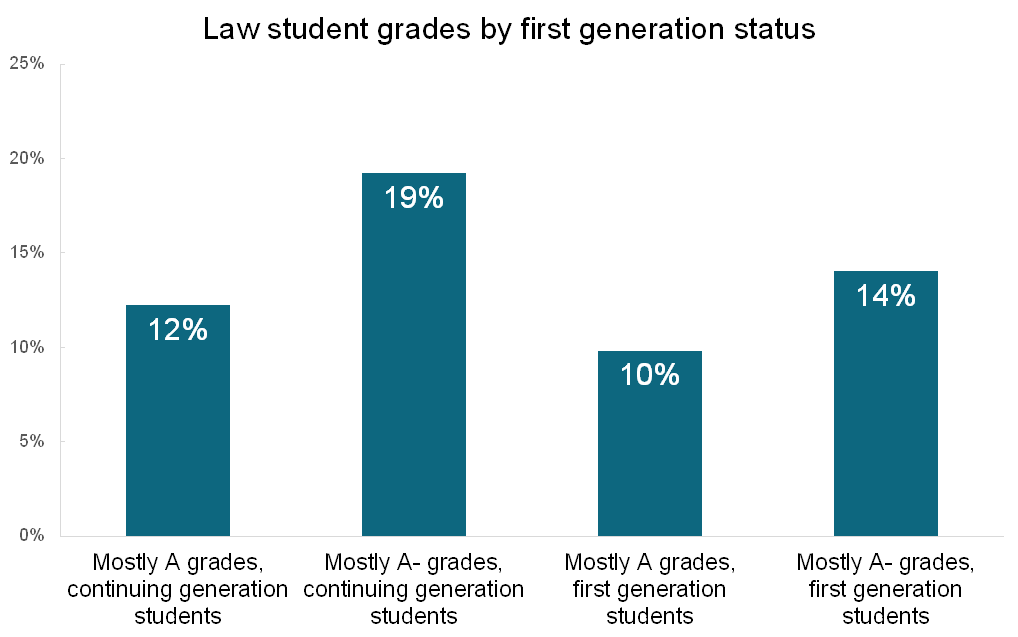

This gap becomes obvious when you look at the data. In the 2021 LSSSE survey, 31% of continuing generation students earned a A- or higher. For first-generation students that number was only 24%. While this might not seem like a staggering gap, without networking and family connections, first-generation students have to rely more heavily on grades for job prospects, so that gap can make a significant difference to their future.[5]

As for social capital, in all professions and cultures there are unwritten rules and norms, generally learned from observing others or knowing people in the culture or profession. Essentially these are not rules you learn about in any explicit way. There is no way for students to study up on these rules, no matter how diligent or well-prepared they are, because they are acquired only through experience. While incoming law students start to pick up on some of these rules during their undergraduate programs, there are still huge gaps where law school and the legal profession are concerned.

Finally, it is far more likely that first-generation students will be providing care for a dependent, either a parent or a child. In fact, 11.3% of first-generation students care for a dependent more than 35 hours per week, as compared to only 5.2% of continuing-generation students.[6] In addition, first-generation students typically end up working more hours, either in legal or non-legal jobs, than their continuing-generation counterparts.

Taken all together, this means that most first-generation students come to law school with considerable hurdles: lower access to finances, lower social capital (i.e., fewer networking connections), lack of exposure to professional norms, and finally, hurdles related to academic preparation, especially when so much of the language used in law school might be brand new to them. And first-generation students themselves know this, coming to law school with concerns surrounding academic success, their career path, building a professional network, finances and family obligations.[7]

What Can We Do?

As legal educators we can do so much. And this starts at the point of admissions. Today, I’m speaking on a panel at LexCon ’22[8] called "Empowering First-Gen Students Through Your Schools' 'Hidden Curriculum,'" along with Morgan Cutright of AccessLex, Teria Thornton, and Susan Landrum, Dean of Students at Illinois College of Law.

Our panel is discussing ways to support first-generation students through the admissions process, navigating financial aid, and finally with academic support once they enter law school. The first step is having these discussions because we often don’t realize the challenges that first-generation students face or what resources they might lack. This is an opportunity for student facing law school professionals – student services, academic support, financial aid, admissions, career services and other administrators – to think through what information we take for granted and then how to make the transition for students a bit easier and more welcoming. For example, even recognizing that many choices they make might be based around financial considerations and scholarships, or staying close to family. Or that purchasing books so that they can read the first class assignment might prove difficult if financial aid checks aren’t distributed before classes begin. Another challenge might be career services assuming that all students have interview appropriate clothes to wear, or can afford such clothes. Some schools have set up interviewing closets where professors and alumni donate old suits for students.

Beyond conversation, at the point of admission, schools can also provide students with a wealth of resources that will help them feel like they belong in law school, and reinforce the message that law school is difficult for all -- not just them. We know that a sense of belonging is linked to positive academic outcomes, such as increased engagement, intent to persist, and achievement[9] However, first-generation students report less belonging, which then increases the achievement gap mentioned above. In addition, students who don’t feel they belong also find it much more difficult to persist in the face of struggle, or even reach out for assistance.

As an example of how we can address a sense of lack of belonging, I used to send incoming students a “law school glossary” upon admissions. It was fairly simple, only a few pages of common words that we tend to use. This was sent to all students, not just first-gen, because some of the terms we use on a daily basis are mystifying to anyone who is new to the study of law. For example, what is a “1L” or what on earth is “K” or “Civ pro”? Abbreviations and acronyms can be just as daunting, and alienating, as the Latin often used.

Because first-generation students often assume that everyone else knows things that they don’t, they might hesitate to ask what are perfectly reasonable questions. Providing them with a quick list of frequently used terms is a great way to decrease feelings of uncertainty. This glossary turned into a book – The First Generation’s Guide to Law School[10] – which was essentially the memo I wish I had received before I started law school. I couldn’t cover everything, but tried to cover most of the unwritten rules surrounding law school, as well as the core academic skills needed to thrive. I wanted to make sure that students could go into their first week of classes feeling confident.

In addition, there are many summer bridge programs that exist. I’m currently working on such a program for the Law School Admission Council (LSAC), and it will be available in the summer of 2023. We had a small bridge program in 2022, Law School Unmasked, and received positive feedback from students on how it increased their feelings of confidence and belonging, and generally increased their ability to succeed in their first semester.[11] For example, “It was very helpful for me as a first generation college and now law student since I do not have anyone I can turn to for help with these topics we went over. Figuring out how things work as a first generation student constantly seems like an uphill battle of asking lots of questions to lots of people who always seem to have vastly different answers and then finding out which answers are correct. This program helped to answer a lot of questions that would have made me feel lost for the first semester of law school.” This shows that programs designed for first-generation students can and do make a difference!

Finally, I encourage all schools to support the formation of a first-generation law student group. This can help ensure first-gen students feel connected, and in a very obvious way, realize they aren’t alone. When I was in law school, I assumed that I might be the only person in the building who didn’t have parents who went to college. However, when I started writing my book – and asking for stories and advice – I discovered that many of my friends and professors were, in fact, also first-generation students. This was shocking to me. So a student group, first and foremost, signals to students that they aren’t the only ones. LSAC is currently working on a National First-Generation Law Student Group, and meeting with already existing student groups to find the best ways to support and foster these types of student organizations.

If you have questions about how to support first-generation students, please feel free to reach out to me at mhale@lsac.org.

[1] Cite 3

[2] FAQ: First-Gen Definition, The Center for First-generation Success, https://firstgen.naspa.org/why-first-gen/students/are-you-a-first-generation-student.

[3] Way back in the dark ages in 2003.

[4] Close the Gap Foundation, last visited May 18th, 2022 https://www.closethegapfoundation.org/glossary/opportunity-gap?gclid=Cj0KCQjwspKUBhCvARIsAB2IYuscRgwXvBQgnHlxQtXJ34Bw4m8g4X_HdMdS_csWATPxgPN0dzuk6eUaAuwKEALw_wcB

[5] id.

[6] Law School Survey on Student Engagement, LSSSE Survey Tool 2021, https://lssse.indiana.edu/about-lssse-surveys/ 1 (Last visited Jan. 17, 2022).

[7] Id.

[8] https://web.cvent.com/event/e2323c1d-5bfb-4ab2-aad0-3cc606276ab1/summary

[9] Id.

[10] https://cali.org/books/first-generations-guide-law-school

[11] https://www.lsac.org/law-school-unmasked

Engagement with Law Student Organizations

Law student organizations are important venues for developing law students’ professional identities. Through networking, invited speakers, and events, these organizations foster a sense of community and provide students the opportunity to more intensely explore areas of law that interest them. [1]

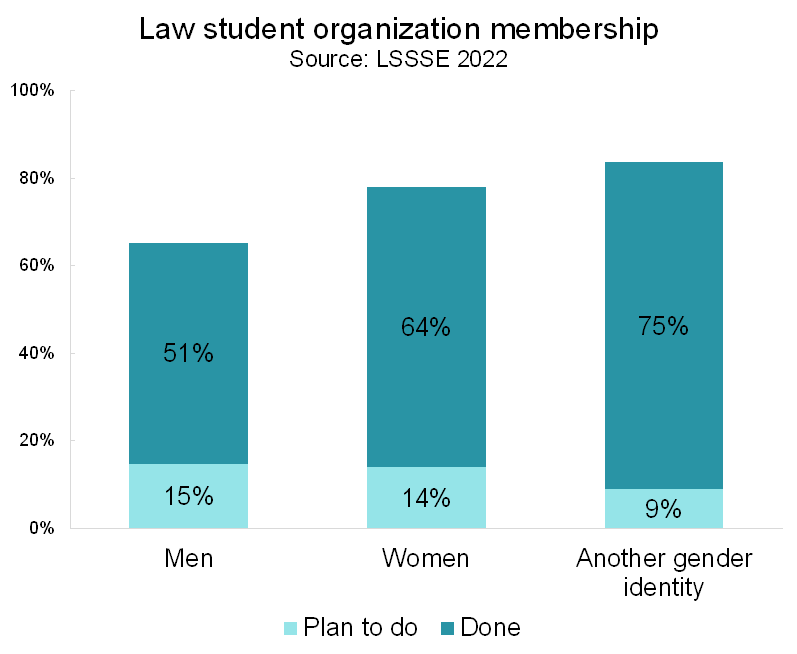

Law student organizations are among the most popular enriching activities at law schools. Nearly three-quarters (73%) of law students either plan to join a law student organization or have already done so. About 31% of students have served as law student organization leaders, and another 18% plan to take on a leadership role before they graduate. Men are less likely to join student organizations compared to women and those of another gender identity. In 2022, just 51% of men had already joined an organization compared to 64% of women and 75% of those with another gender identity.

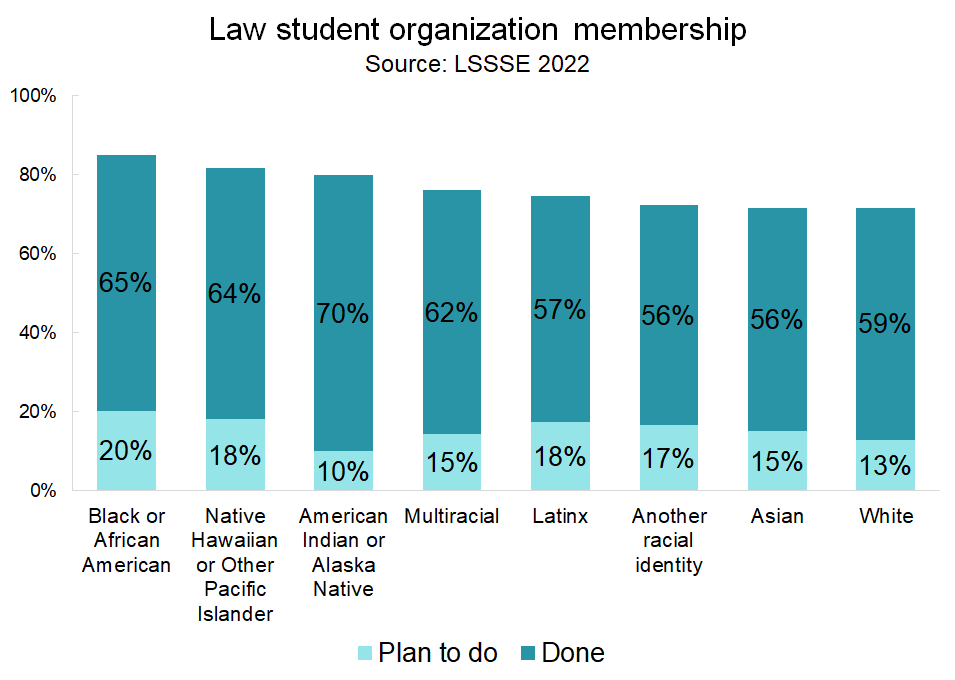

Black students are particularly engaged as members of law student organizations, with 65% of Black students participating and another 20% planning to do so. Native Hawaiian students, American Indian students, and Alaska Native students have similarly high levels of engagement with law student organizations, while Asian and white students have the lowest participation rates.

Women, gender-diverse people, and students of color are most likely to join student organizations. Thus, these organizations likely play a vital role in connecting law students who traditionally face higher barriers in accessing higher education and assimilating successfully into the legal profession. Law student organizations also given students the opportunity develop their leadership skills and to work with their professors and classmates in a non-classroom context.

____

[1] See Andrew Hitt, The importance of student organizations, (Aug. 27, 2009), https://law.marquette.edu/facultyblog/2009/08/the-importance-of-student-organizations/

A Critical Tool for Dean and Faculty Leaders

A Critical Tool for Dean and Faculty Leaders

Austen L. Parrish

Dean and Chancellor’s Professor of Law

University of California, Irvine School of Law

The job of a law school dean has changed. If once to be “successful... you need[ed] to be a distinguished scholar,” now the day-to-day responsibilities of a law dean are much more varied and complex. Just recently, a piece in Bloomberg Law explained that if the “[l]aw school dean once was a dream job . . . [t]hese days, the position is more like being chief executive of a sprawling business than a tweed-clad dispenser of constitutional wisdom.” A landmark Association of American Law School’s study on the American Law School Dean underscored that during the pandemic deans spent considerable time on crisis management, on issues related to diversity, equity, inclusion, and on topics of student life and student conduct. The pressures of continued intense hyper competition—whether that’s recruiting and retaining talented students, faculty, and staff; the complexity and demands of core operations, including admissions, career services, communications, finance, student services, among others; and the need to enhance the school’s research, teaching, and service missions, while navigating complex university labyrinths—in many ways reflects that higher education itself operates in a much more complex context than it once did.

As the role of the dean has become broader and more complex, the need for quality data upon which to track progress and base decisions has become more important. In the last decade, the resources available to law deans have expanded dramatically. AccessLex Institute’s Analytix, which aggregates ABA data about legal education, its research and data portal, and its annual legal education data deck are some of the best and most useful examples. The AALS compendium of data resources, the Law School Admission Council’s data on admissions and student recruitment, and the National Association of Law Placement’s research and statistics are others. In my own experience, when it comes to gauging student engagement and the student experience, few resources are more useful than the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE).

LSSSE helps with data-driven decision-making. Schools that have consistently taken advantage of LSSSE now have a wealth of longitudinal information from over 17 years of surveys. I’ve found, however, that the survey also has a more straightforward function. If we care about our students and their experiences, why wouldn’t we want to track and measure student perceptions of that experience? And tracking those perceptions over time provides some indication of whether we’re making progress on our goals. Comparisons with other institutions are useful in creating benchmarks too. For standing faculty committees focused on curriculum, student support, or student success, LSSSE provides a way to take stock of how a school is collectively doing and whether the initiatives being implementing are moving the needle.

LSSSE helps with data-driven decision-making. Schools that have consistently taken advantage of LSSSE now have a wealth of longitudinal information from over 17 years of surveys. I’ve found, however, that the survey also has a more straightforward function. If we care about our students and their experiences, why wouldn’t we want to track and measure student perceptions of that experience? And tracking those perceptions over time provides some indication of whether we’re making progress on our goals. Comparisons with other institutions are useful in creating benchmarks too. For standing faculty committees focused on curriculum, student support, or student success, LSSSE provides a way to take stock of how a school is collectively doing and whether the initiatives being implementing are moving the needle.

Personally, I have found it’s the bread-and-butter questions of the survey that are most helpful. How satisfied are our students in the career counseling, personal counseling, academic advising, financial aid counseling, as well as library and technology assistance they receive? How often and in what ways do our students interact with faculty? The responses don’t tell you as a dean or a faculty committee what to do, and the questions measure perceptions as much as anything, but the survey responses provide important insight into the extent our students are feeling supported, and whether we’re building the inclusive, rigorous academic community we want. And on a year-to-year basis, the survey provides red flags and early warning signals if there’s a sudden drop in an area. It also provides reasons for celebration and congratulations to staff over sustained improvement. Of course, if you care about fundraising, questions asking students to evaluate their overall law school experience, and whether if they could start over they would attend the same law school, are critical. And for being a dean in California, where the bar exam is notoriously exclusionary, the new AccessLex and LSSSE partnership that seeks to explore the connections between student engagement and bar performance is a welcome development.

I’ve found LSSSE useful in other ways too. For one, LSSSE’s special reports have been insightful on providing a perspective on issues that I care about, and that I know many of my dean colleagues care about too. The 2020 Annual Report, Diversity & Exclusion, or the special report on The Changing Landscape of Legal Education, which provides a 15-year retrospective, both come to mind. More pragmatically, as the ABA Section on Legal Education has required that schools track and assess outcomes, LSSSE and its Accreditation Report and Accreditation Toolkit provide near essential tools in demonstrating compliance with accreditation requirements. I’m puzzled how some schools—unless they are doing extensive annual surveying in a different form—are easily able to show compliance with all the new standards without using LSSSE.

I’ve found LSSSE useful in other ways too. For one, LSSSE’s special reports have been insightful on providing a perspective on issues that I care about, and that I know many of my dean colleagues care about too. The 2020 Annual Report, Diversity & Exclusion, or the special report on The Changing Landscape of Legal Education, which provides a 15-year retrospective, both come to mind. More pragmatically, as the ABA Section on Legal Education has required that schools track and assess outcomes, LSSSE and its Accreditation Report and Accreditation Toolkit provide near essential tools in demonstrating compliance with accreditation requirements. I’m puzzled how some schools—unless they are doing extensive annual surveying in a different form—are easily able to show compliance with all the new standards without using LSSSE.

LSSSE has been useful for another reason. LSSSE now houses the largest repository of law student data in the U.S. with over 400,000 responses over seventeen years. That’s a powerful tool for researchers, but it’s also just helpful for deans to do their jobs. It’s not enough for a law dean to know what’s happening in their own school. Alumni, provosts, presidents, and other stakeholders want to know trends in legal education. Having a broader, empirical view of the changes of legal education is useful to rebut persistent misinformation and caricatures about legal education.

LSSSE has shown how legal education has changed in the last seventeen years. The surveys show that there’s room for innovation and improvement and that rising student debt remains a concern. Yet on balance the surveys tell a positive story of school success. Overall levels of satisfaction remain high, and schools have made progress in improving the quality of legal education and the commitment to student support. While variation between law schools can be significant, the surveys reveal an American legal education system that is increasingly diverse, has strong student services with engaged full-time teachers and scholars, and underscores that schools overall have strengthened their commitment to supporting students in their path to launching satisfying careers (with academic, career, and personal advising).

LSSSE is a valuable tool for deans. One that I’ve used consistently over the last decade, and one I will continue to use.

Relationships with Law Faculty

Law students generally have strong relationships with law school faculty members. In 2022, 71% of LSSSE respondents ranked their relationships with faculty a 5 or higher on a 7-point scale, where 7 represents faculty who are “available, helpful, and sympathetic.” Only 12% of students ranked their relationships a 3 or lower, and a mere 1% of students ranked their relationships a 1, meaning they feel that the faculty at their law school are “unavailable, unhelpful, and unsympathetic.”

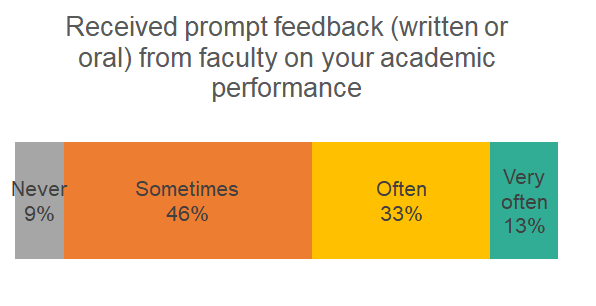

Relationships with instructors are built both inside and outside the classroom. More than half (53%) of law students discussed assignments with a faculty member often or very often, and only 5% never discussed assignments with a faculty member. After completing assignments, most law students (91%) receive prompt feedback from faculty on their academic performance at least sometimes. However, only 13% say they receive prompt feedback very often, and 9% never receive prompt feedback.

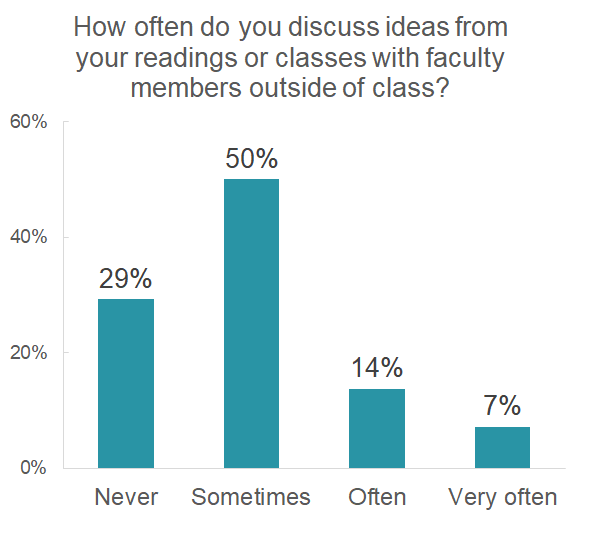

About one in five students (21%) often or very often discussed ideas from their readings or classes with faculty members outside of class, and another half (50%) did so sometimes. This practice tapers off a bit over time, with 22% of first-year students discussing ideas with faculty members outside of class often or very often compared to 19% of 3Ls and 11% of 4Ls.

Law school faculty can provide crucial guidance about navigating the legal job market, and the vast majority of students (84%) take advantage of their advice. Just over a third of students (36%) discuss their career plans or job search activities with a faculty member of advisor often or very often. Around 82% of first-generation students (neither parent holds a bachelor’s degree) have discussed their career plans with faculty compared to 85% of their non-first-generation peers.

The relationships students form during their time in law school can be crucial to their future success. The majority of law students make the most of these relationships, and they appreciate the support and knowledge they receive from the faculty of their law schools.

Guest Post: What’s Actually At Stake in the SCOTUS Challenge to Race-Conscious Admissions

Shirley Lin, Assistant Professor of Law

Brooklyn Law School

Clara Williams ‘23

Brooklyn Law School

Consider the following hypothetical law school candidate. She is a child of limited-English-proficient immigrants, growing up in a majority-minority neighborhood of Queens, New York. Her community and adjoining zipcodes had been deprived of public investment for decades. She and her siblings were the first in their household to graduate high school, then college. Because of their race and ethnicity, they experienced harassment from a young age and, one of them, a violent beating in high school. By the time she applied to law school, she took her first course in standardized testing just before her second and final attempt on the LSAT. Co-author Professor Lin’s experience with affirmative action in higher education would have been markedly different if the Supreme Court decides to overturn four decades of precedent allowing schools’ admissions programs to consider race along with other factors.

After decades of being held up as a racial foil against other communities of color in racial politics—especially in debates over affirmative action—Asian American communities are wary of being used as pawns to undo efforts to address racial inequality. After withstanding repeated challenges to affirmative action, in 2003, the Court reaffirmed the current doctrine that admissions programs may consider race among other factors that contribute to campus diversity in Grutter v. Bollinger. In tandem appeals against Harvard and University of North Carolina, petitioner Students for Fair Admissions (or SFFA, led by a white affirmative action opponent, Edward Blum), now seeks to do so again in a bid to undo the practice of race-conscious admissions entirely.

Statistics are central to SFFA’s challenge on several levels: in evaluating how interested parties have positioned racial categories; in illustrating what is at stake; and in contextualizing the relevance of these appeals to legal education. In fact, for nearly a decade, the majority of Asian American voters have supported affirmative action—today, at nearly 70 percent. This includes the 6,000-member Harvard Asian American Alumni Alliance (H4A, representing all of Harvard’s Schools), which joined amici student and alumni groups supporting Harvard’s ability to consider race in its admissions process. H4A has underscored that a racially diverse student body creates the best educational environment for everyone—including Asian Americans.

Emphasizing a consistent line of studies demonstrating that racial diversity increases tolerance and empathy across racial lines, the Asian American Legal Defense & Education Fund filed an amicus brief last month in support of the respondent universities, on behalf of 121 AAPI scholars and community group signatories (including Professor Lin). Amici highlighted the meteoritic rise in anti-Asian American hate crimes, in particular extremely violent attacks and murders, that persist, in emphasizing the continuing relevance of the benefits of racial diversity that Grutter recognized two decades ago.

Numbering at least 24 million, Asian American communities are kaleidoscopically diverse even in terms of ethnicity and class stratification alone. Asian Americans have undergone profound changes in the last two decades. Their cultural and political experiences nationwide defy pat generalizations about race, phenotype, immigration status, religion, and experiences with language barriers. For example, 12 of 19 subgroups by Asian origin analyzed by the Pew Center currently experience poverty at rates as high as—or above—the level for overall U.S. population. Today, roughly 6 in 10 U.S.-born Asian Americans are members of GenZ (i.e., aged 22 or younger), and another 25% of the population considered Millennials. Their experiences in schools (including legal education) defy the racial stereotypes of Asian Americans that formed a generation or two ago as the “model minority” who can simply, meritocratically, join the middle- or upper-middle-class.

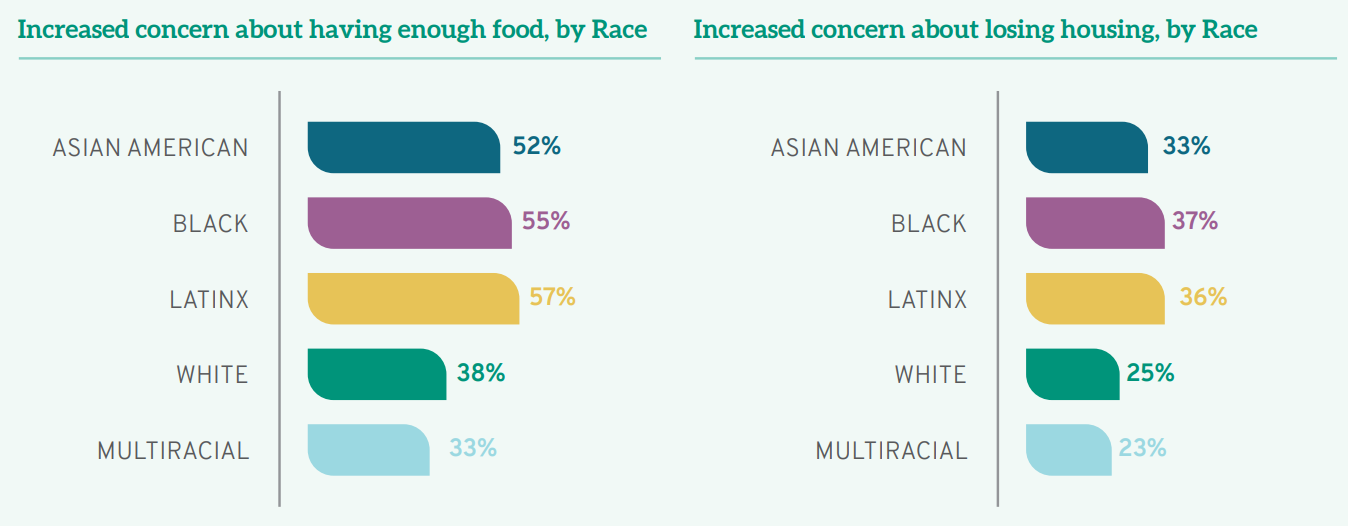

Recent reports from the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) provide a far more accurate picture than the briefs provide. For example, during the ongoing COVID crisis, concerns about access to adequate food and housing among Asian American law students were on par with Black and LatinX law students:

LSSSE, The COVID Crisis in Legal Education (2021)

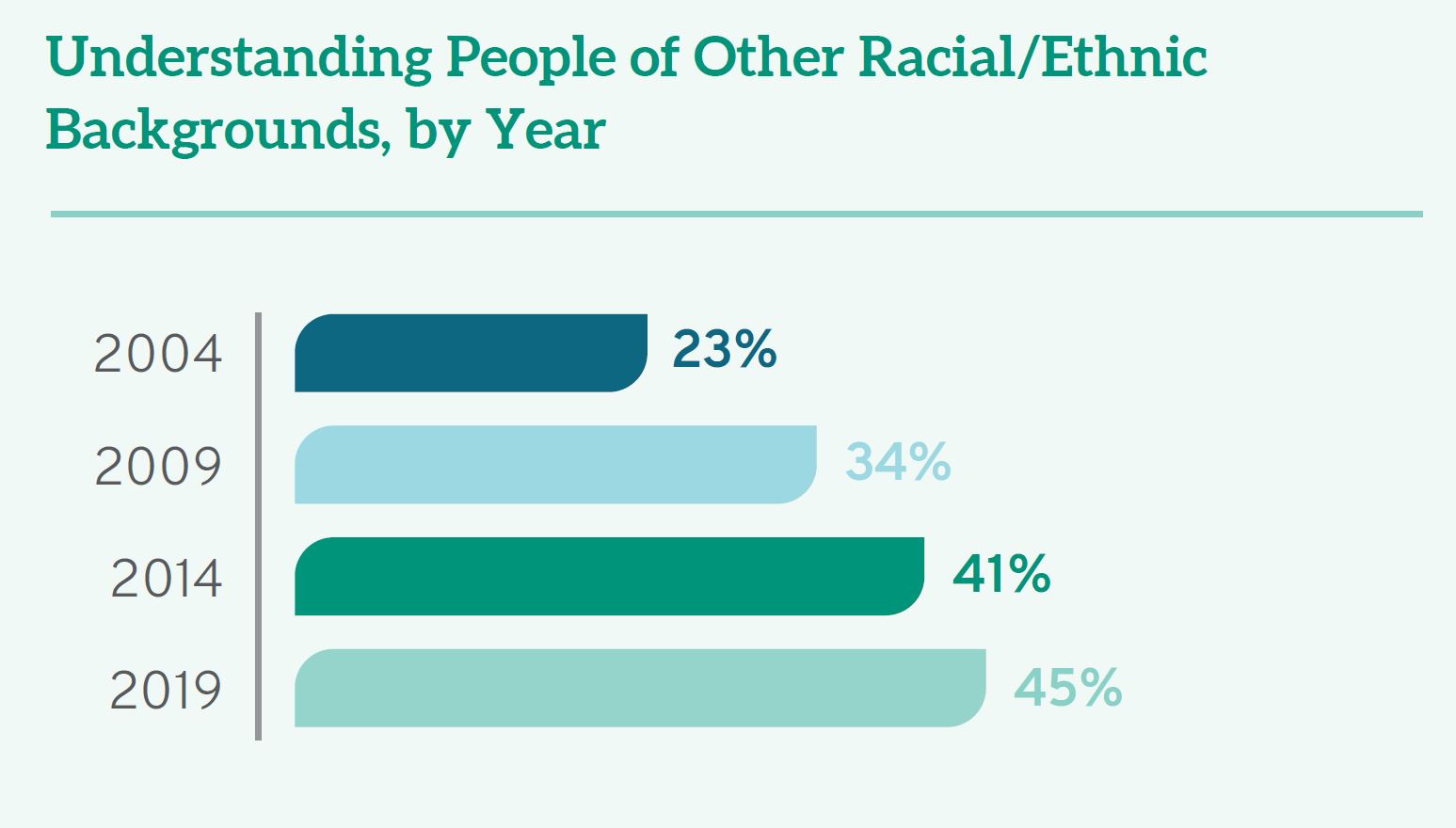

Meanwhile, LSSSE’s 2020 report providing a 15-Year Retrospective reflects that, in the intervening time since Grutter and its subsequent increase in student racial diversity, students were twice as likely to report that their law school contributed to their understanding people of other racial or ethnic backgrounds— progressing from a paltry 23% to 45%:

These students’ experiences, of course, predate the ABA’s modest revision earlier this year of law school Accreditation Standard 303(c), which now states: “[a] law school shall provide education to law students on bias, cross-cultural competency, and racism: (1) at the start of the program of legal education, and (2) at least once again before graduation.”

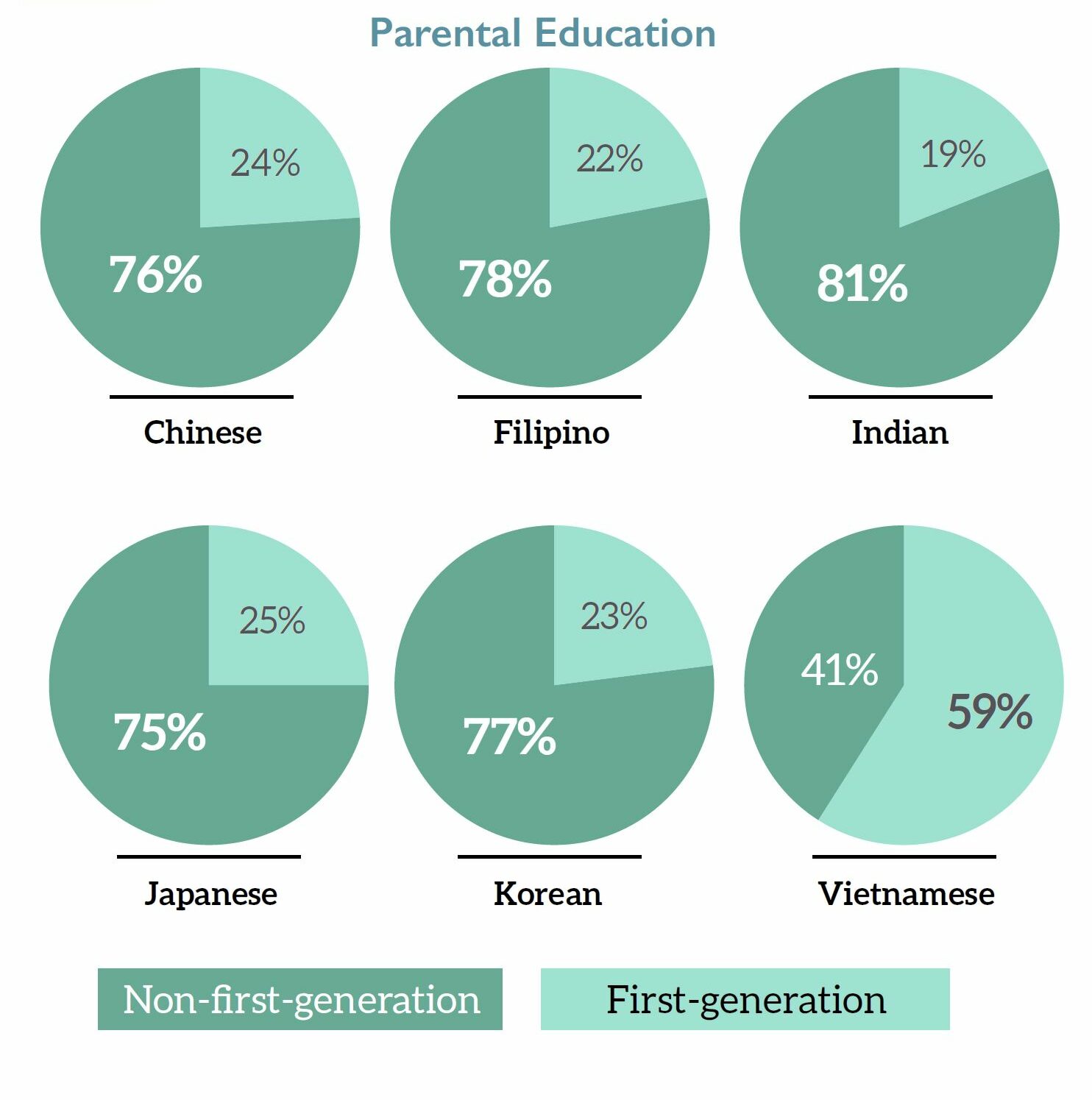

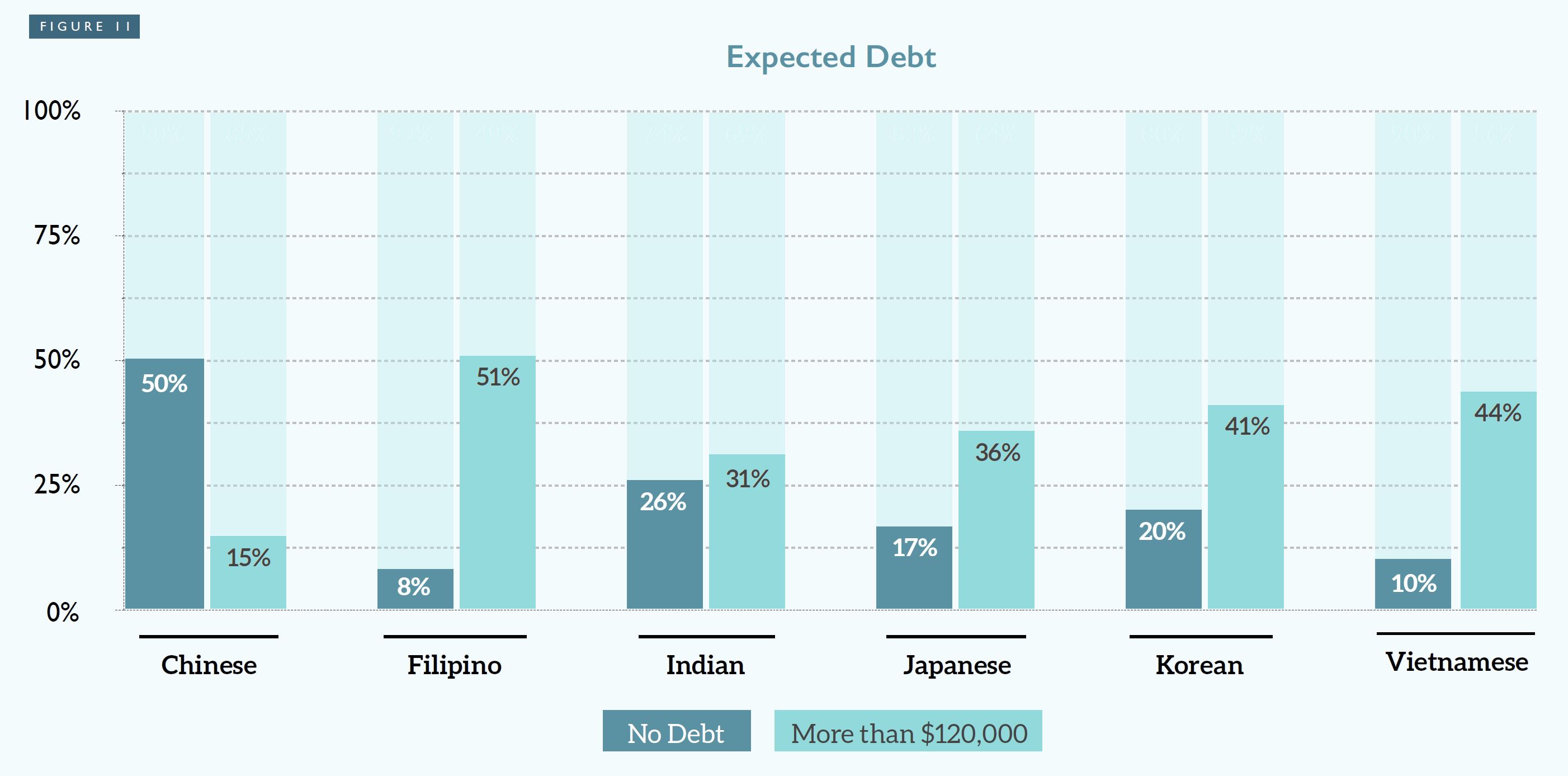

Taking time to drill down into the experiences of subgroups within Asian American communities yields a wealth of information about the similarities and, perhaps just as crucially, the divergent experiences of such a vast grouping. For instance, Vietnamese American students are half as likely as Indian American students to have parents who received a college education. Chinese students comprise 50% of the international students, who are generally not eligible for merit-based scholarships.

Diversity Within Diversity (2017)

Most troubling is that, in its Harvard litigation, SFFA claims to be concerned with assisting AAPI applicants against “negative action” by proposing as an alternative affirmative action based solely on income. Yet the group avoids acknowledging that such plans ultimately provide the greatest boost to white applicants—not racial minority applicants—because they do not account for additional systemic hurdles racial minorities from impoverished families face. Meanwhile, a ruling that would prohibit the use of race while leaving in place “colorblind” practices that unfairly benefit wealthy white applicants belies SFFA’s professed concern for Asian American applicants.

Rather than confounding admission programs, our current doctrine on race-conscious affirmative action does not prohibit law schools or colleges from assessing the multiple dimensions of advantage and disadvantage as they intersect with race (including for white applicants). To the contrary, it expects schools to assess individual applicants holistically. Students of color—including Asian American students—overcome barriers to the profession compounded by race alongside class, disability, gender, and other dimensions of inequality. Professor Lin’s first-hand experience with the inequities her family and neighbors faced remained central to her pursuit of legal advocacy, and now research and teaching, which investigate how law binds racial and economic injustice. Her unlikely route to academia would scarcely have been possible without the nuanced, race-conscious approaches intact in current doctrine.

Nonetheless, conservative proponents of “colorblindness” will soon ask the Justices to discard nearly 50 years of settled law on race-conscious admissions programs in higher education. At a time when debates over K-12 curricula foreground ideological attempts to silence all conversation about the ways in which race fosters systemic and institutional inequality, SFFA’s blunderbuss legal challenge has—at a minimum—reinvigorated examination of actual racial diversity so that legal academia, too, must take note.

New Questions Focusing on Law Students with Disabilities

By popular demand, LSSSE is now capturing information about the experience of law students with disabilities. Law students are given the opportunity to select one or more conditions using the following questions:

Have you been diagnosed with any disability or impairment?

- Yes

- No

- I prefer not to respond

Which of the following impacts your learning, working, or living activities?

- Sensory disability

- Blind or low vision

- Deaf or hard of hearing

- Physical disability

- Mobility condition that affects walking

- Mobility condition that does not affect walking

- Speech or communication disorder

- Traumatic or acquired brain injury

- Mental health or developmental disability

- Anxiety

- Attention deficit or hyperactivity disorder (ADD or ADHD)

- Autism spectrum

- Depression

- Another mental health or developmental disability (schizophrenia, eating disorder, etc.)

- Another disability or condition

- Chronic medical condition (asthma, diabetes, Crohn’s disease, etc.)

- Learning disability

- Intellectual disability

- Disability or condition not listed

- Please describe your disability or condition

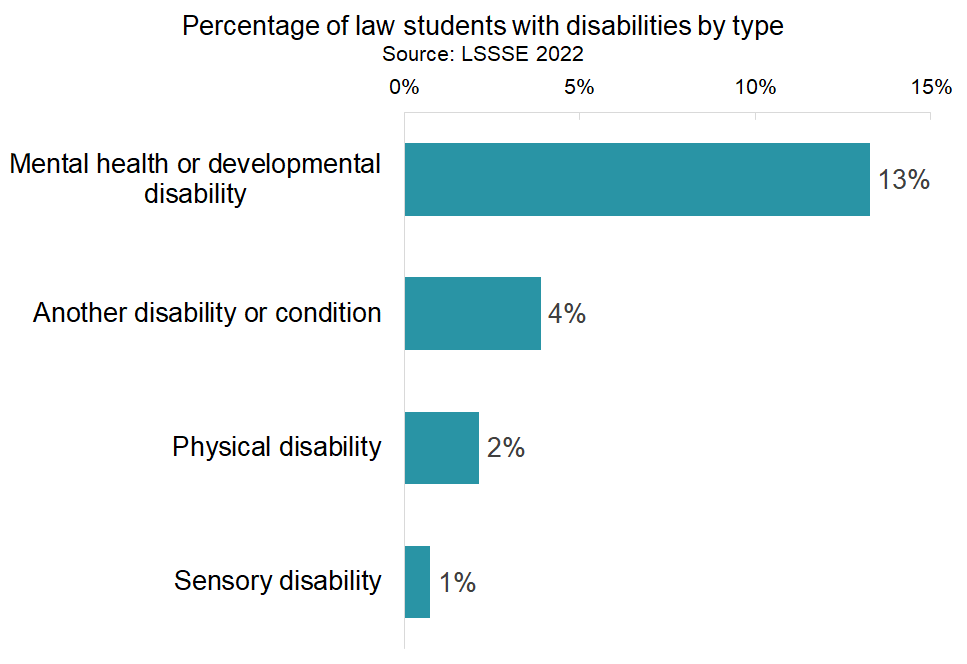

In 2022, nearly one in five (19%) of LSSSE respondents had a disability. Students who responded "yes" to the disability question then had the option to select the condition(s) that impact their learning, working or living activities. Mental health conditions were by far the most common, with about 13% of law students having a condition such as anxiety, ADHD, or autism. Four percent of law students had a condition not specified on the survey such as a chronic health condition or a learning disability. Two percent of respondents had a physical disability, and one percent had a sensory disability such as being deaf or hard of hearing.

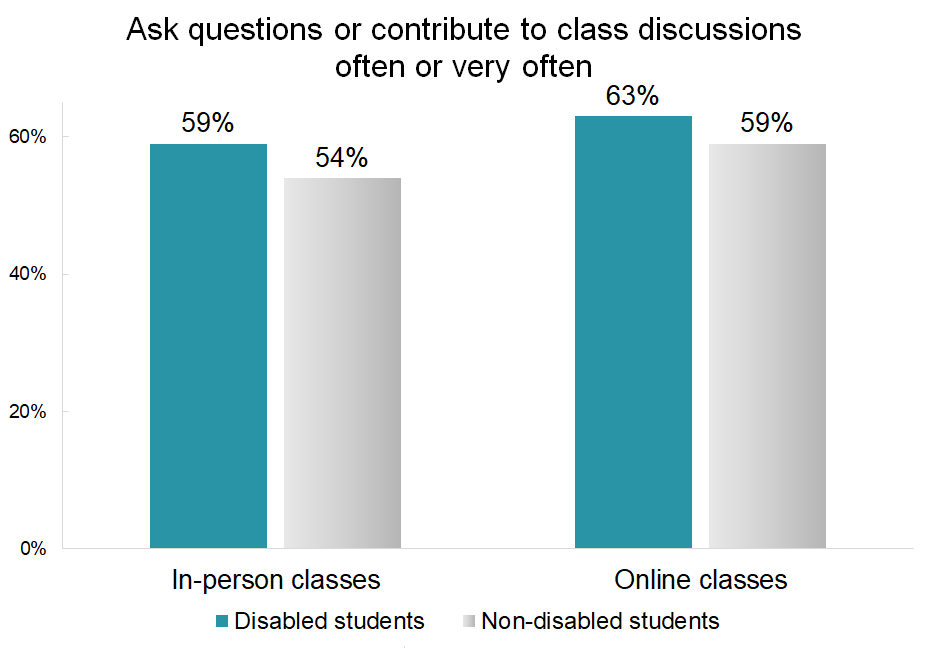

In addition to tracking the overall proportion of law students who are disabled, these new data give us an exciting opportunity to explore how students with disabilities might engage differently with their law schools and what particular experiences or services law schools can offer to better help these students succeed as professionals. For example, law students who have a disability are more likely to participate in class discussions, both online and in person, compared to their non-disabled peers. Additionally, students with disabilities are more likely to engage in pro bono work or public service during law school. Near four out of five students with disabilities (79%) either plan to or have done pro bono work or public service compared to 74% of non-disabled students.

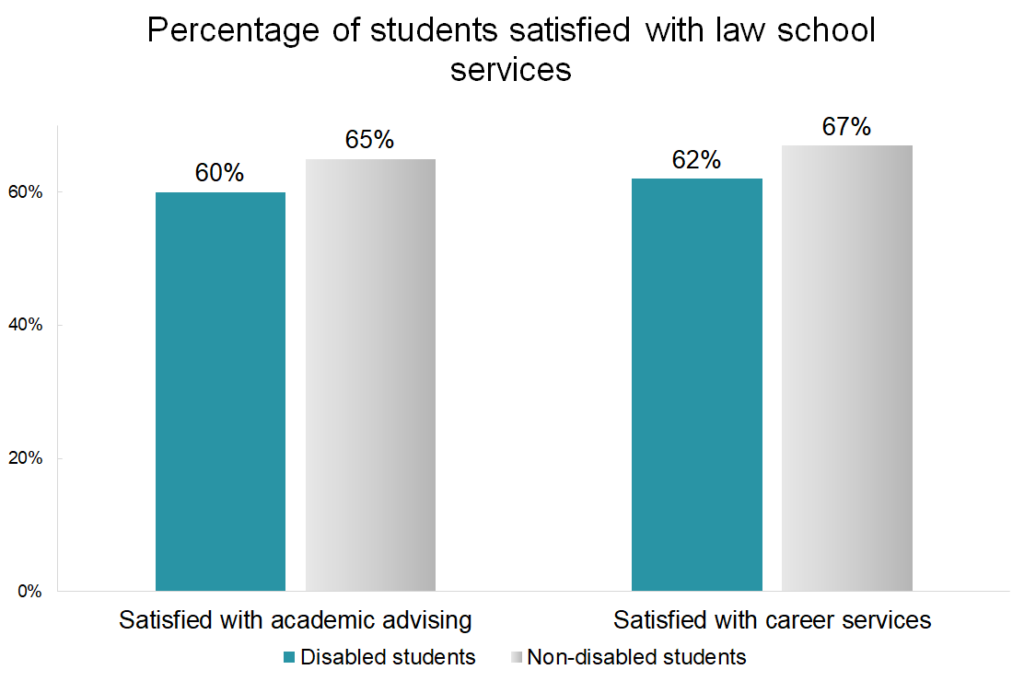

However, disabled students are less likely to be satisfied with their experiences with academic advising and career advising compared to their classmates. This suggests that law students with disabilities engage intensely with the law school experience but do not always feel as supported as their non-disabled peers.

The new disability questions are included in the core LSSSE survey and available to all participating law schools. Survey registration will be opening soon; contact LSSSE for more details!

Providing the support law students need to succeed academically

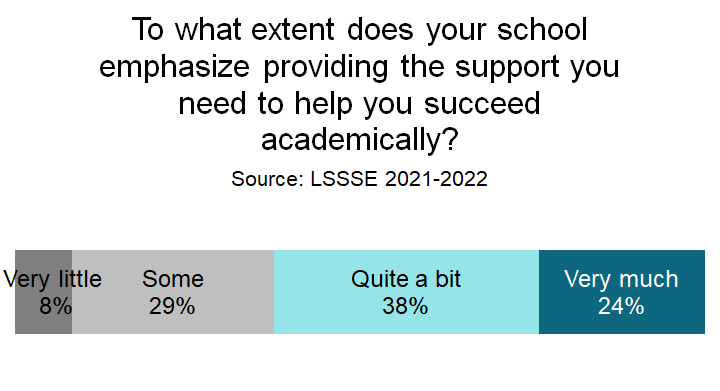

A strong academic program is the foundation of any law school. Equally important is that law schools provide the support services students need to meet the rigors of the curriculum. About two-thirds of law students feel that their law school places “quite a bit” or “very much” emphasis on providing the support they need to succeed academically.

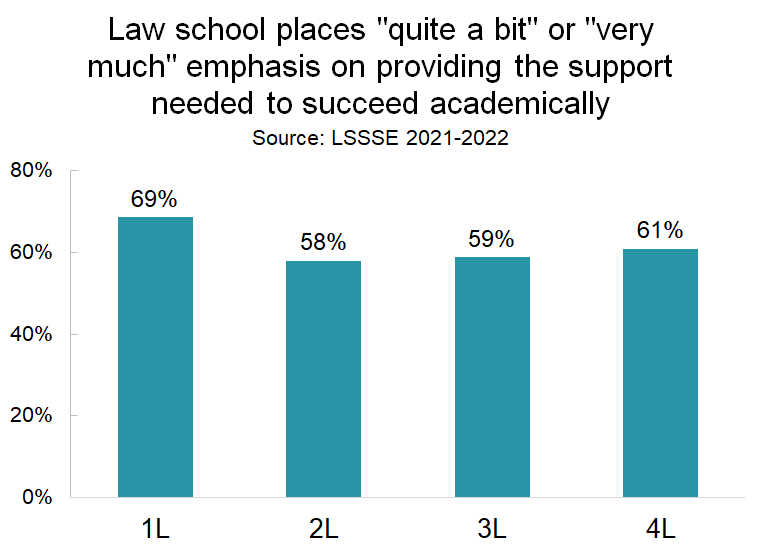

1L students are more likely to feel supported than their more advanced colleagues. Although the general optimism and positivity that 1L students feel toward their experience tends to steadily decline with advancing years for any measure of engagement, for the perception of academic support, satisfaction drops markedly among 2L students and then remains at that level during 3L and 4L years. This suggests that there is an initial sense of being supported that fades fairly quickly after students adjust to their new environment.

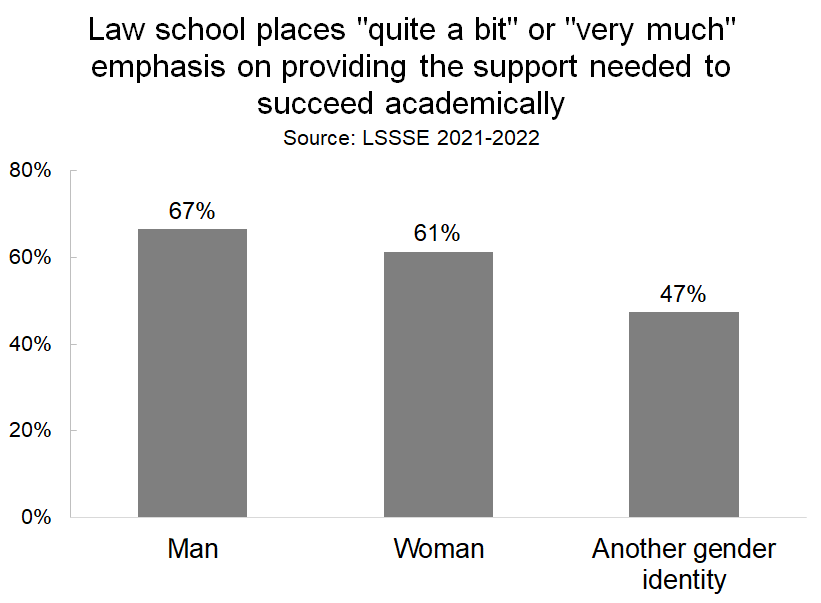

Two-thirds of men feel that their law schools places a strong emphasis on supporting academic success, which is slightly higher than the proportion of women who feel similarly (60%), but fewer than half of the people who have another gender identity feel that level of academic support.

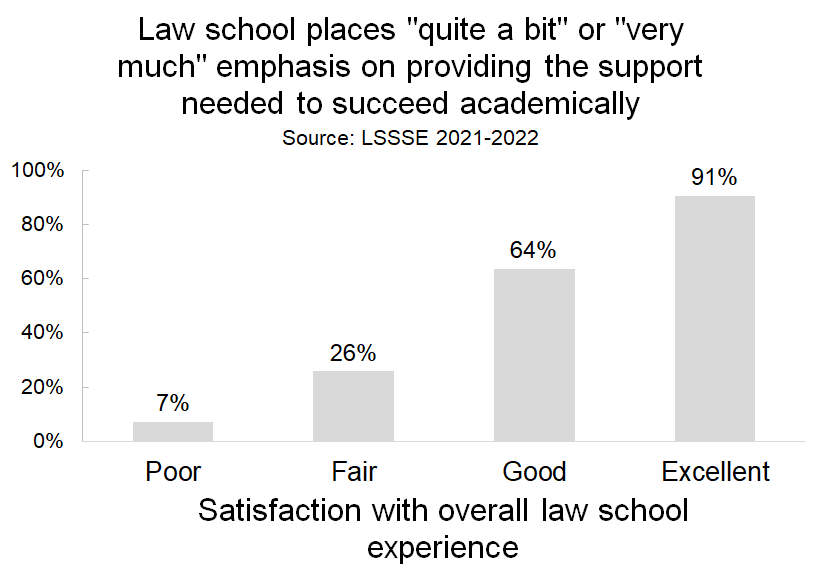

Importantly, the degree to which students feel academically supported is very strongly correlated with whether they are satisfied with their overall law school experience. A full 91% of students who rate their experience as “excellent” feel supported in their academic success compared to only 7% of students who have are having a “poor” experience.

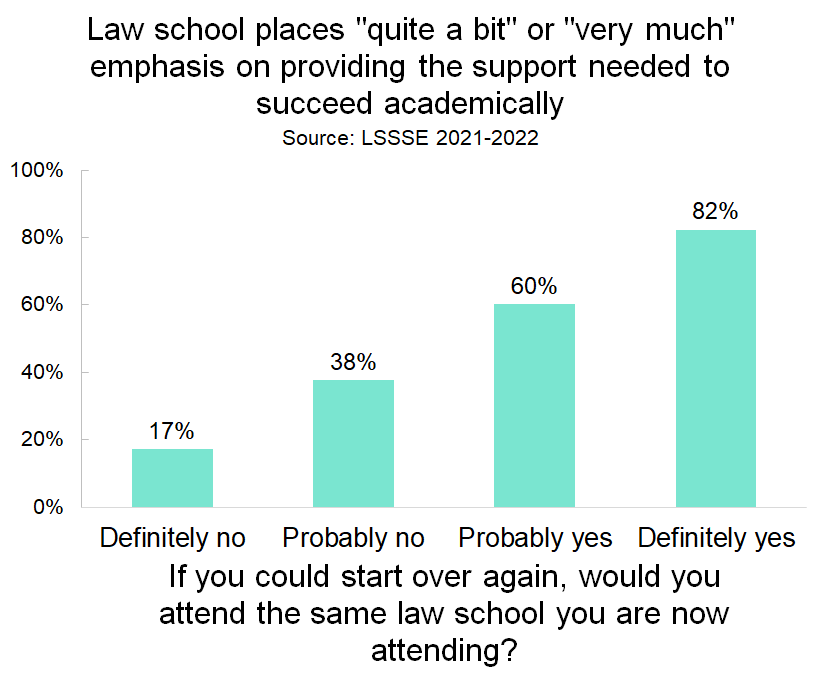

Perceived degree of academic support is also closely tied to whether a student would choose their law school again if they could start over, although the relationship is slightly less stark than for overall law school satisfaction. Among students who would either probably not or definitely not attend the same school, about 32% feel supported to succeed academically. But among students who would probably or definitely attend the same school, 70% feel academically supported.

Law students are driven to succeed in the face of the challenges presented by their academic program. Students who feel supported in their academic endeavors by their schools are more likely to be satisfied with their overall experience and to say that they would choose the same school if they could start over. Academic support is integral to a successful law school experience and likely impacts students’ long-term satisfaction and likelihood to become alumni who speak highly of their alma maters.

Guest Post: Using Meaningful Admissions Data to Improve Legal Education and the Profession

Anahid Gharakhanian

Vice Dean & Director of the Externship Program

Professor of Legal Analysis, Writing, and Skills

Southwestern Law School

Natalie Rodriguez

Associate Dean for Academic Innovation and Administration

Associate Professor of Law for Academic Success and Bar Preparation

Southwestern Law School

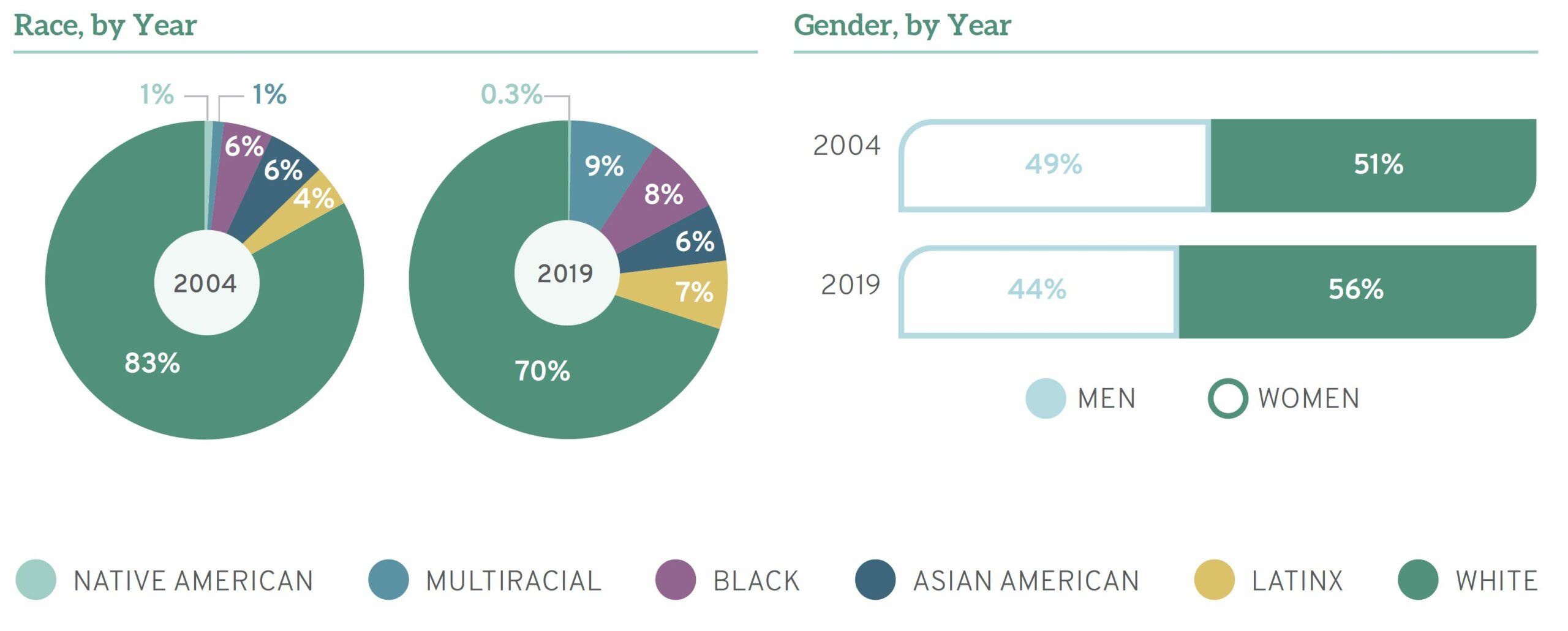

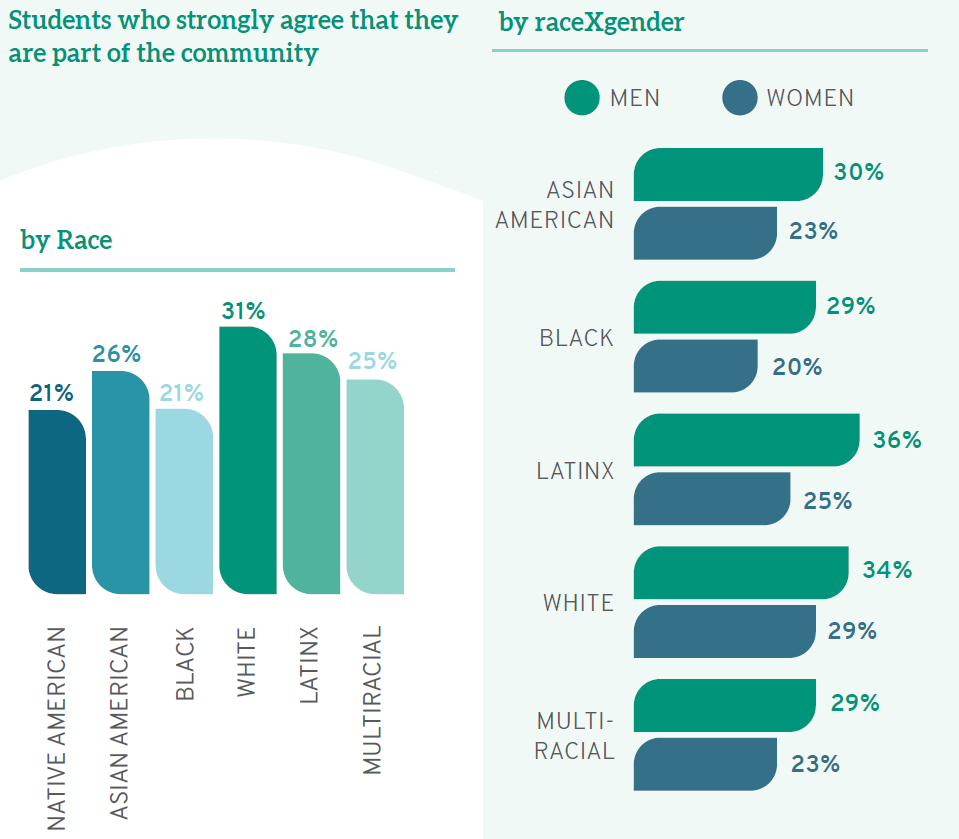

Conversation about increasing diversity and doing better when it comes to inclusion and belonging is everywhere in legal education. What’s critical though is empirically tracking how well we’re actually doing. The Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) provides invaluable and sobering data that should serve as a beacon to legal educators’ aspirational goals of cultivating diversity, inclusion, and belonging in their schools and in the profession. LSSSE’s 15-Year Retrospective – The Changing Landscape of Legal Education – tells us that there’s a positive trajectory with minority enrollments from 2004 to 2019.

But the jarring news is that minority students’ sense of belonging – especially women of color students– is quite a bit lower than that of White students. As LSSSE’s 2020 Diversity and Exclusion Report points out, “Scholarly research indicates that students who have a strong sense of belonging at their schools are more likely to succeed.”

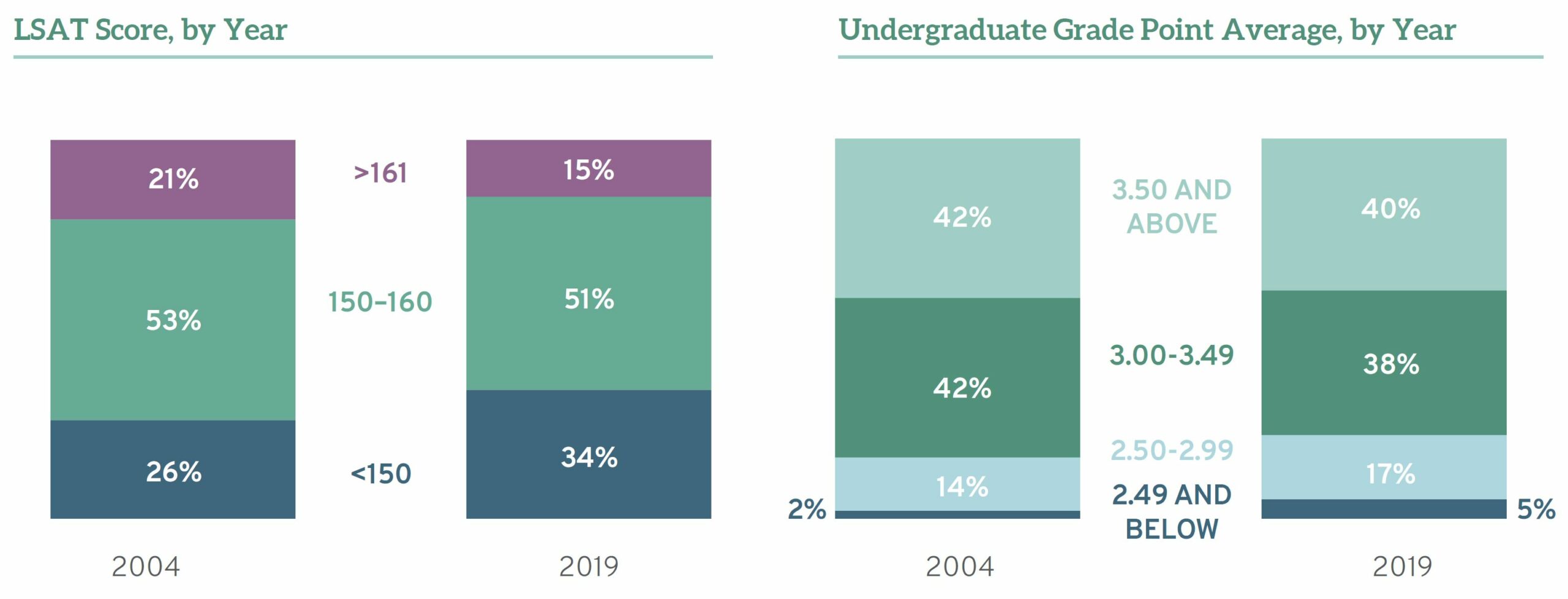

The data unequivocally tells us that we need to do a lot better for ALL law students to succeed. But the effort should start much earlier than when law students start law school. We need rigorous rethinking and innovation in law school admission practices – whereas to date the hyper-focus is on the limited numerical indicators of undergraduate GPA and especially LSAT score.

For the past three years, Southwestern Law School has innovated with such a first-of-its kind approach to admissions practices. The research project and initial results are detailed in “More than the Numbers”: Empirical Evidence of an Innovative Approach to Admission, Minnesota Law Review (Vol. 107, forthcoming), co-authored by the co-authors of this blog and Dr. Elizabeth Anderson, and will be presented at the Minnesota Law Review Symposium, on October 7, 2022, “Leaving Langdell Behind: Reimagining Legal Education for a New Era.” Interestingly, Southwestern’s empirically-based novel approach seems to have provided a notable boost to the matriculants’ sense of confidence or belonging in attending law school. More on that in a bit.

Southwestern’s project is driven by the moral imperative that law schools – as gatekeepers to the legal profession – should commit to innovative and rigorous admissions processes that define merit broadly and provide opportunities based on a spectrum of factors, beyond the traditional numerical indicators. In furtherance of this commitment, several years ago, Southwestern developed an evidence-based tool to more fully and meaningfully assess applicants’ law school potential. This tool goes beyond the limited cognitive measure of the LSAT, which many criticize as an impediment to diversifying law schools and the profession and which at best is only modestly predictive of first year law school performance.

Southwestern’s approach focuses on that group of applicants whose application materials show promise but also raise questions about the applicant’s current readiness for law school. These applicants are invited to participate in a methodical waitlist interview process where they are asked a series of questions based on several factors identified in the IAALS’s Foundation for Practice (“Foundations”) study as necessary for first-year attorneys. Three years into this project and based on hundreds of admission interviews working with Dr. Elizabeth Anderson we have analyzed our approach. The data has produced initial reliability and validity metrics for the measure developed – i.e., a tool that could be used with confidence in the admissions process.

Southwestern’s approach has included three steps. First, Southwestern identified what needs to be measured – i.e., certain foundations necessary for first-year practice as established by the Foundations study and hence assumed to be necessary to law school success. Second, the school identified why these factors need to be measured – i.e., to provide access to legal education with measures that matter. Third, the school designed the empirical research to support the development of a reliable and valid measure of this construct. Relatedly, Southwestern developed a measure of “nontraditional readiness for law school” using a design that focused on a psychometric research design, where psychometrics is the research practice of formal development of reliable and valid measures/assessments. Southwestern has found that the developed tool/measure is measuring what it set out to measure. This tool/measure will produce a score that will then be used in predictive validity analyses, as well as predictive modeling of law school success outcomes.

Interestingly, and beyond the quantitative data, based on comments shared by the interview matriculants, for purposes of adding context to the paper we’ve written about the admissions project, we’ve learned that the interview experience provided a notable boost to their confidence in attending law school. This was not an outcome that Southwestern had hypothesized or planned for but was a palpable part of the comments shared by the matriculants. Seeing the LSSSE data about belonging, it’s imperative that we create a sense of belonging starting with the admissions process.

The matriculant’s comments are indelible. A third-year interview matriculant noted:

I was very nervous when I came to the school for the waitlist interview. But afterward I felt heard and this motivated me. It gave me confidence, and I felt I couldn’t let the school down and I now had the opportunity to follow my purpose.

A second-year interview matriculant noted:

With the waitlist interview, Southwestern made the admissions process more personal and it showed me that the administration really values the lived experience of potential students and wants to hear what I have to say. This gave me confidence about law school and what I can contribute/accomplish.

And a first-year interview matriculant noted:

My waitlist interviewer dug deep and tried to understand me. She heard me, which was incredible. I knew law schools aren’t comfortable taking a chance but I was hoping some schools would want to hear my story and that’s what the waitlist interview did for me. This gave me the chance and confidence to pursue the dream that started with watching Fresh Prince of Bel-Air when I was a kid and thinking it’s so incredible to see Black attorneys and I want to be an attorney.

Our work has been well-received. We recognize, however, there is work left to be done and LSSSE is uniquely positioned to contribute in this area and help drive the necessary change through additional data. As part of its annual survey, LSSSE could include questions designed to gather data on law students’ admissions experiences. As our approach to admissions shows, establishing a sense of belonging can begin well before orientation. This unintended yet profound outcome is worth additional exploration. As indicated in the 2020 Diversity and Exclusion Report, a strong sense of belonging can make the difference in whether a student feels they have the support they need to thrive, especially women of color.

Further, as part of its longitudinal studies, LSSSE could also consider ways to track admissions factors beyond the limited indicators of LSAT and UGPA. The 2020 15-Year Retrospective – The Changing Landscape of Legal Education points out overall drops in UPGAs and LSAT scores.

This is helpful information, but the continued hyper-focus on these traditional factors, and not probing into and tracking other admissions-related data, contributes to perpetuation of limiting entry into law school and the profession based on narrow concepts of merit and potential.

These are just a few ideas. But to be sure, empirical inquiry and evidence must lead the way to change in admission practices. With its dedication in working for the betterment of legal education and its rigor in research practices, LSSSE certainly has a critical role to play in encouraging innovative law school admissions practices that more fully and meaningfully assess merit and potential while creating an inclusive and engaging pre-matriculation experience.

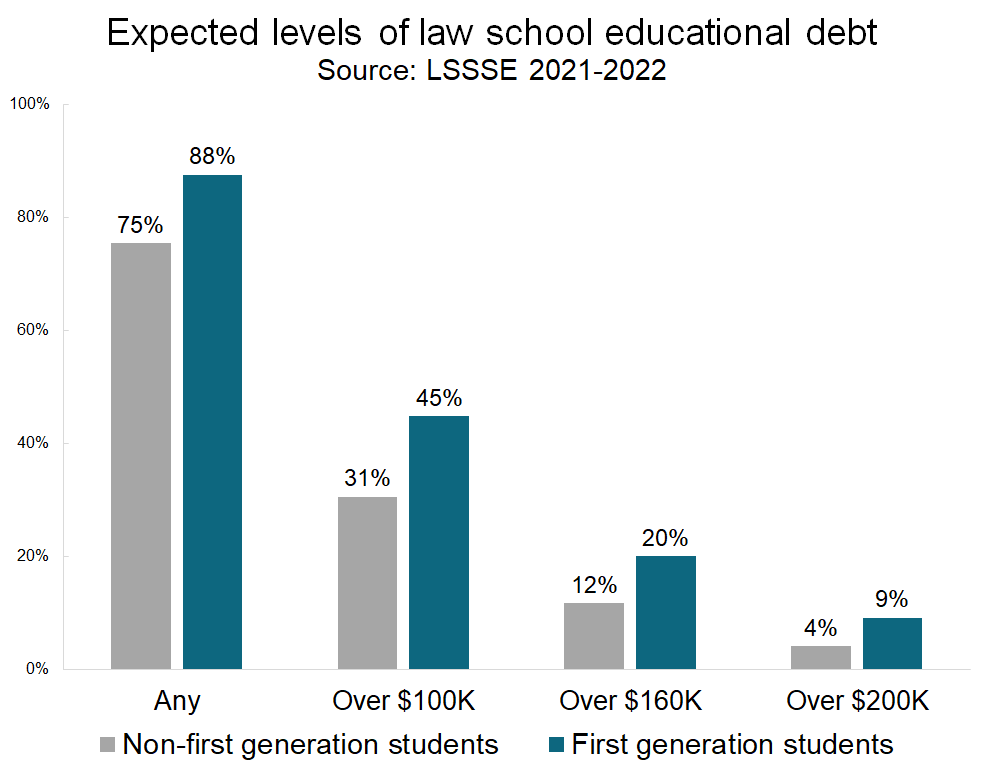

First Generation College Students Bear More Law School Debt

First generation law students, defined as those students who do not have at least one parent with a bachelor’s degree, face unique hurdles in higher education. In addition to navigating an unfamiliar cultural landscape, first generation students may be particularly challenged by financial concerns and student debt. In fact, although 75% of non-first generation law students expect to have some debt from attending law school, that number climbs to 88% for first generation students.

Additionally, the total dollar amount owed in student debt tends to be higher for first generation students. LSSSE 2021 and 2022 survey data show that first generation law students expected to owe an average of $96,000 compared to $71,000 for their non-first generation classmates. Around 45% of first generation students expected to owe over $100,000, but only 31% of non-first generation students expected to have loan balances that high. Shockingly, first generation students are twice as likely as their non-first generation peers to owe more than $200,000, which is the highest debt category recorded by LSSSE. Only four percent of non-first gen students fall into this category, compared to a full nine percent of first gen students.

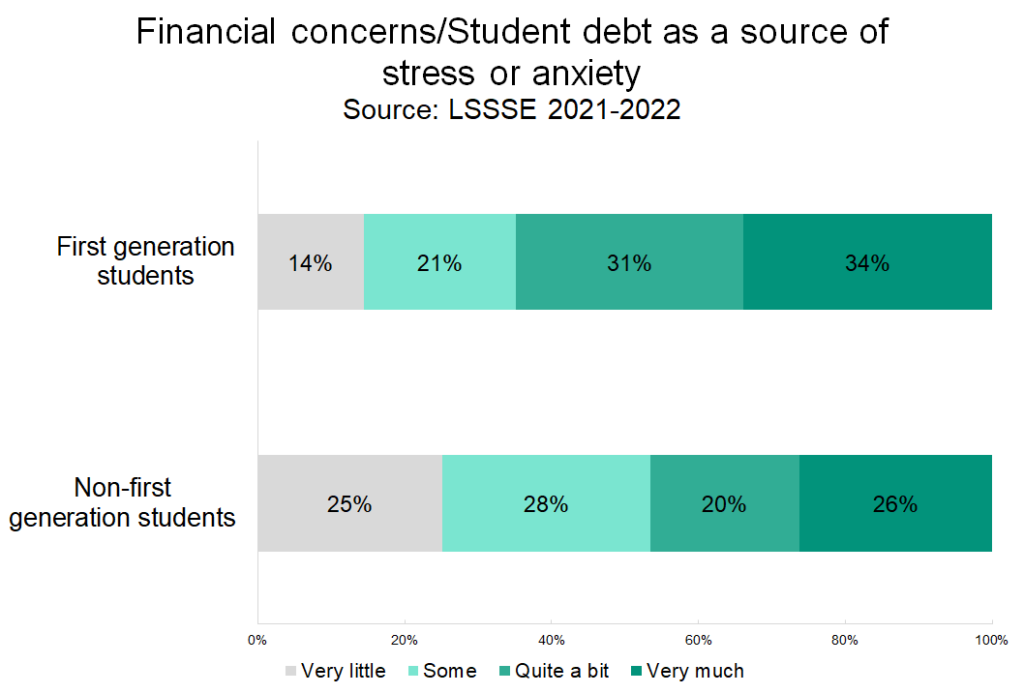

The differing financial picture for these groups of students takes an emotional toll. Although first gen and non-first gen students report similar stress levels related to law school (about 84% rank their stress a 5 or higher on a 7-point scale), two-thirds of first gen students say that financial concerns and student debt are a big source of stress or anxiety compared to less than half (46%) of non-first gen students.