LSSSE Annual Results 2019: The Cost of Women’s Success (Part 2)

Contextualizing Women’s Success

Women’s relative success in law school is quite significant when we consider basic demographic differences between women and men when they first enroll in law school. Fewer economic resources and lower test scores do not seem to inhibit women from achieving at high levels once on campus.

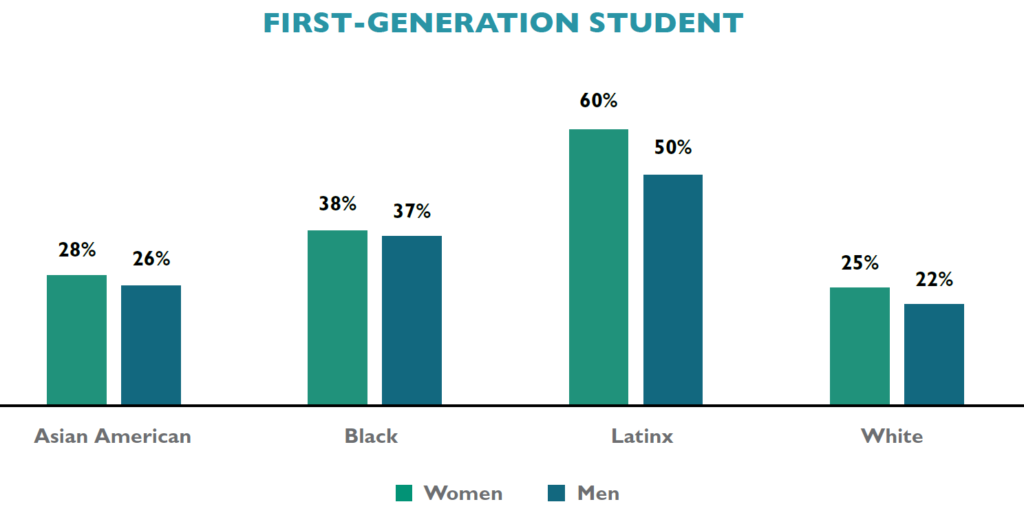

Parental education is a common proxy not only for family income but for future educational success, with the children of highly educated parents generally drawing on class privilege and extra resources to achieve at high levels. LSSSE data reveal that women are more likely than men to be first-generation law students, with 30% reporting that neither parent holds a bachelor’s degree as compared to 25% of male law students. This finding is consistent for women regardless of race/ethnicity, with Asian American, Black, Latinx, and White women being more likely than men from those same backgrounds to be the children of parents who did not earn at least a college degree.

Even considering those whose parents are highly educated, women law students are less likely than men to have a parent who is a lawyer. Among those reporting that they have a parent who earned a doctoral or professional degree, 57% of men but only 52% of women report that their parent’s degree is a J.D. Only Asian American women are more likely than men from their same racial/ethnic background to have a parent with a law degree; higher percentages of male law students who are Black, Latinx, or White have a lawyer parent than women from those same backgrounds.

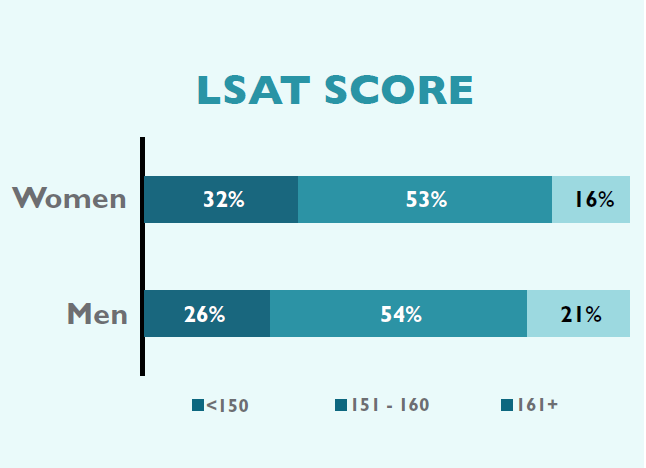

In addition to demographic differences based on parental status, women also report lower LSAT scores than men, even when comparing within racial/ethnic groups. While 21% of men report LSAT scores in the highest range of 161 or above, only 16% of women report similar achievement on this exam. This finding mirrors other critiques of high-stakes testing as potentially limiting opportunities for non-traditional students including women and people of color.

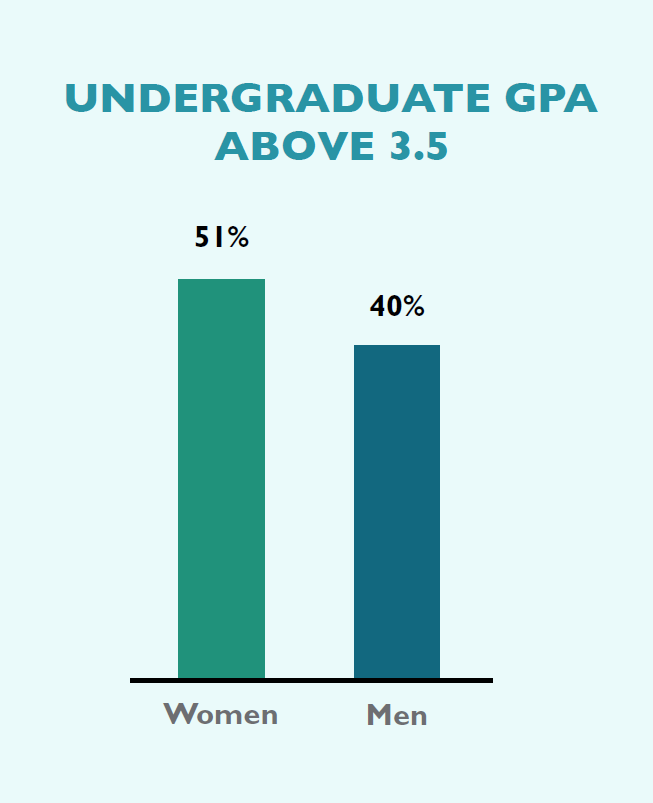

Conversely, higher percentages of women than men enter law school with undergraduate grade point averages (UGPAs) in the top range. A full 51% of women report UGPAs of 3.5 and above as compared to only 40% of their male classmates. As with LSAT scores, this gender finding is consistent across race/ethnicity: when comparing women and men from the same background, women outperform men on UGPA. Recall that in spite of the inconsistency of lower LSAT scores and higher UGPAs, women nevertheless report slightly higher overall law school grades than men. This may further bolster research questioning the value of using test performance as the primary determinant of expected success in law school and beyond.

The next post in this series will offer some opportunities for improvement in gender equity in legal education. You can read the entire LSSSE 2019 Annual Results The Cost of Women’s Success (pdf) on our website.

LSSSE Annual Results 2019: The Cost of Women’s Success (Part 1)

The past two decades have seen increasing numbers of women in law schools. After graduating from law school, women lawyers enjoy greater opportunities for financial independence, security of employment, and a potential for leadership facilitated by the J.D. degree. Yet, gender inequities in pay and position continue to plague the legal profession. In spite of this conundrum, there has been little scholarly attention given to the experience of women while in law school.

The 2019 LSSSE Annual Results celebrate women. We investigate the successes of women law students—using objective and subjective measures to reveal various accomplishments. We also interrogate their backgrounds and the context for their enrollment in law school, revealing challenges women overcome and the sacrifices they make to succeed. This Report not only shares findings on women as a whole, but also features comparisons by gender and race/ethnicity, providing greater depth and context to the overall experience of women law students. Our findings make clear that women’s success comes at great personal and financial cost. Greater awareness of these challenges provides both an imperative and an opportunity for administrators, institutions, and leaders in legal education to invest more deeply in the success of women.

The Good News

Women are succeeding in legal education along numerous metrics. When considering overall satisfaction rates, roughly equal percentages of women (81%) and men (83%) report that their entire experience in law school has been either “Good” or “Excellent.” In spite of generally high marks for all groups, there are notable differences by race/ethnicity. While the vast majority (75%) of Black women characterize their overall experience as positive, these rates are lower than those of women who are Asian American (78%), Latina (78%), and White (84%).

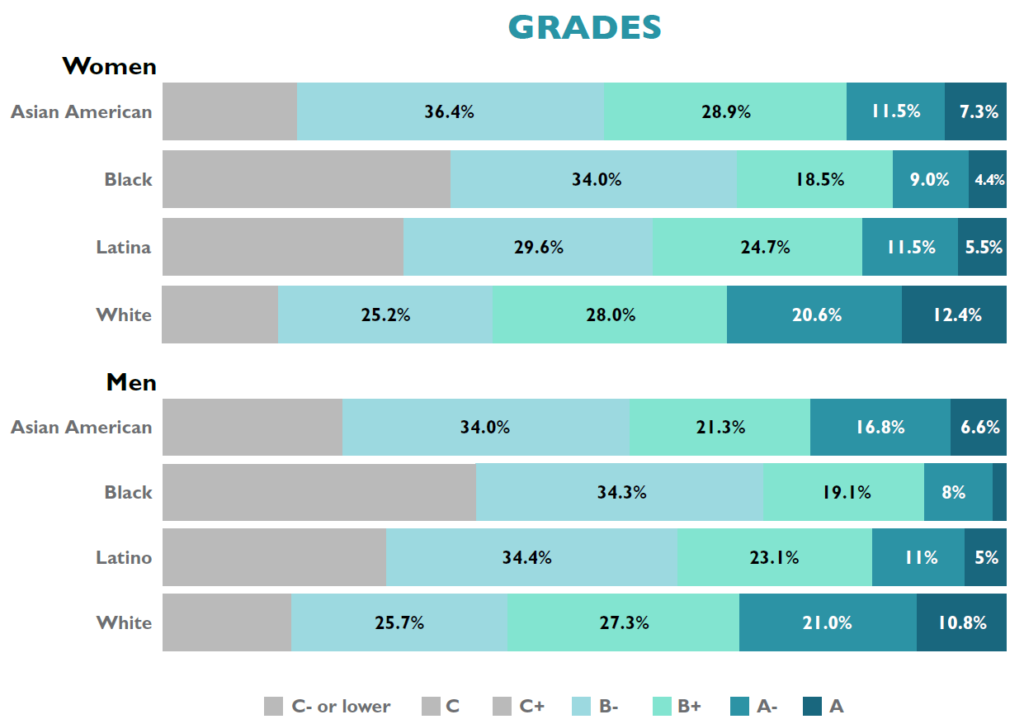

In addition to appreciating their law school experience, women are also excelling academically. Women’s self-reported law school grades are slightly higher than men’s. As one example 10.3% of women report earning mostly A grades in law school compared to 9.5% of men. There is important variation not only by race but also by the intersectional consideration of raceXgender. To start, 7.3% of Asian American women, 4.4% of Black women, and 5.5% of Latinas claim mostly A grades as compared to 12% of White women law students. Yet, when investigating grades within each racial/ethnic group by gender, women are nevertheless outperforming men.

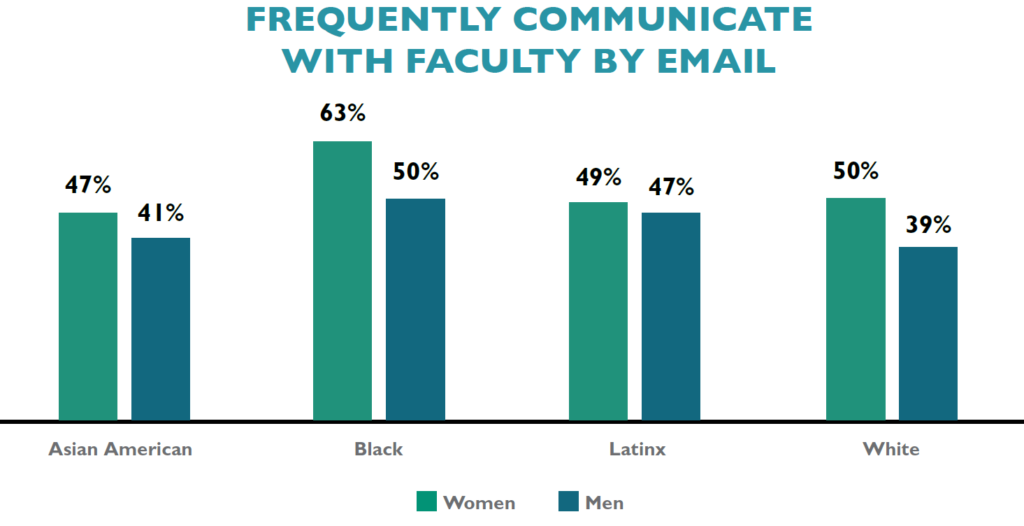

Additionally, women are adept at utilizing particular resources in law school, connecting with faculty and fellow students. Just over half (51%) of women use email to communicate with a faculty member “Very often” compared to only 40% of men. In fact, at 63%, Black women are more likely to engage in frequent email contact with faculty than any other raceXgender group. Women, regardless of their racial/ethnic background, are also more likely than men on average to engage in ongoing and frequent conversations with faculty and other advisors about career plans or job search activities. Women and men are also engaged in co-curricular activities at roughly equivalent rates, including the percentages participating in pro bono service, moot court, and law journals. A majority of students also enjoy positive interactions with classmates. A full 79% of men and 75% of women report the quality of their relationships with peers as a five or higher on a six-point scale. Furthermore, 65% of women rely on and invest in membership in law student organizations—which research has shown provide social, emotional, cultural, and intellectual support for many students. Black women (68%), Latinas (65%), Asian American women (60%), and White women (65%) join student groups at higher rates than men as a whole (53%).

Women are clearly engaged members of the law school community. Our next post in this series will discuss contextual differences between men and women before entering law school that suggest women are more likely to have to overcome obstacles to be successful. You can read the entire LSSSE 2019 Annual Results The Cost of Women’s Success (pdf) on our website.

Annual Results 2018: Relationships Matter – Student Relationships

Decades of research on student engagement and student learning demonstrate the importance of peer interactions. Engaging with classmates in meaningful ways contributes to a deeper sense of belonging and enhances understanding of classwork, leading to better academic and professional outcomes (Hurtado & Carter, 1997; Pascarella & Terenzini, 2005; NSSE, 2013).

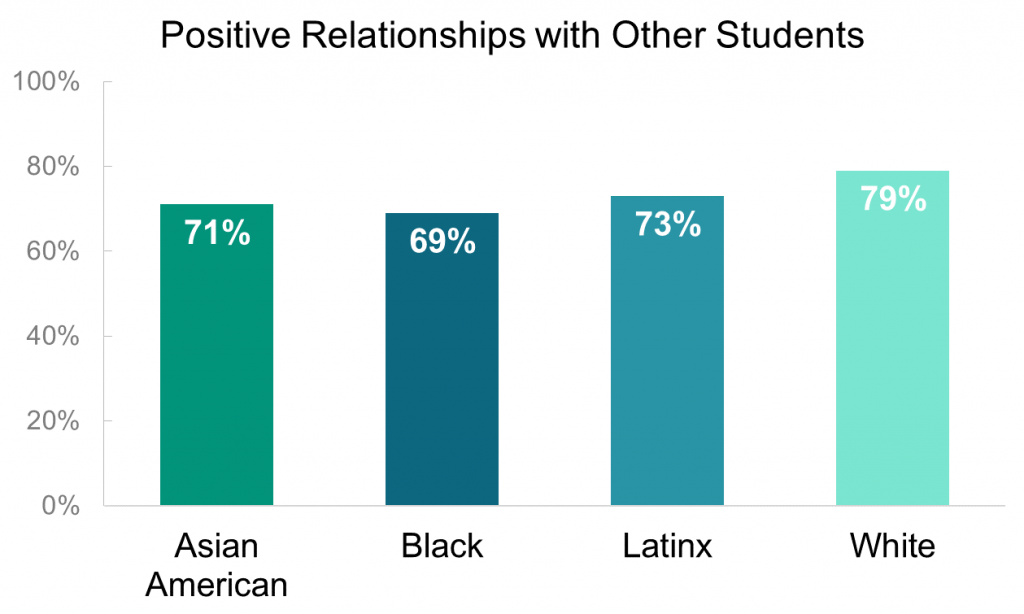

Although law school is an inherently stressful and anxiety-producing endeavor, the vast majority of students (76%) report that their peers are friendly, supportive, and contribute to a sense of belonging. There are noticeable variations by race/ethnicity. White students are most likely to report positive relationships with peers (79%), as compared to Black (69%), Asian American (71%), and Latinx (73%) students.

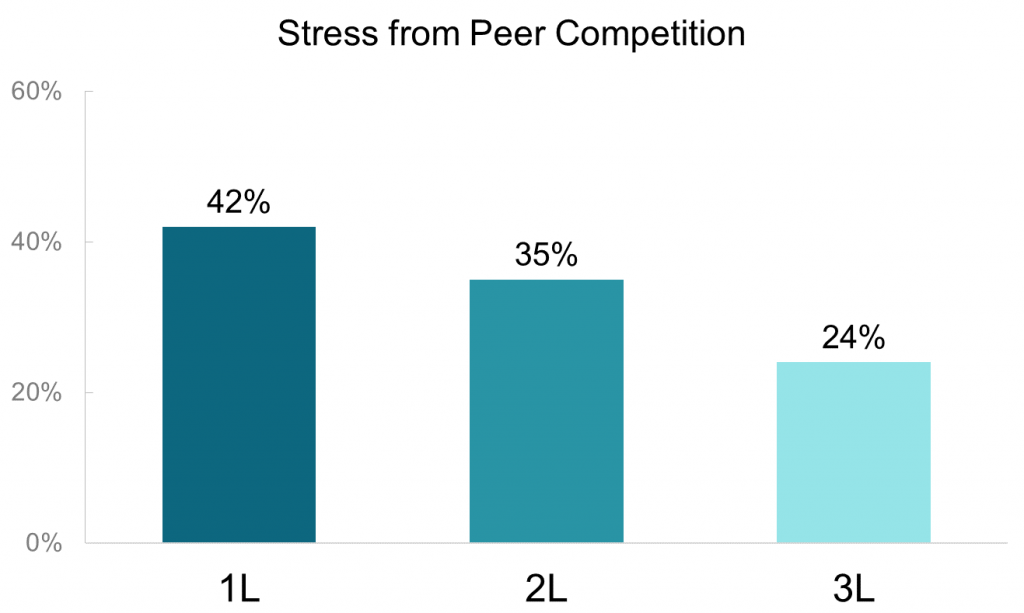

The Student Stress Module examines law student stress and anxiety—their sources, impact, and perceptions of support offered by law schools to manage stress and anxiety. One question asks directly about various sources of stress and anxiety that students may face in school. High percentages of students report that academic performance (77%) and academic workload (76%) produce stress or anxiety, but competition amongst peers does not create or magnify these feelings for most students. Students report that competition amongst peers is most significant during the first year of law school but sharply declines each year. Forty-two percent of 1L students report that peer competition is a source of stress or anxiety. By the third year of law school that number drops to 24%.

Annual Results 2018: Relationships Matter – Advising

A majority of students are pleased with the quality of advising and their relationships with administrators:

- 69% are satisfied with academic advising and planning.

- 66% are satisfied with career counseling.

- 64% are satisfied with job search help.

- 70% are satisfied with financial aid advising.

- 68% report that administrative staff are helpful, friendly, and considerate.

The quality of relationships with advisors and administrators is both positive and relatively consistent across race, gender, and year in school. Seventy percent of 1L students (and 67% of 2Ls and 3Ls) report that administrative staff are helpful, considerate, and flexible. Seventy-nine percent (79%) of students consider at least one administrator or staff member as someone they could approach for advice or guidance on managing the law school experience. Higher percentages of Black students (87%) rely on these relationships than students from other racial backgrounds (79% for Asian American, white, and Latinx students).

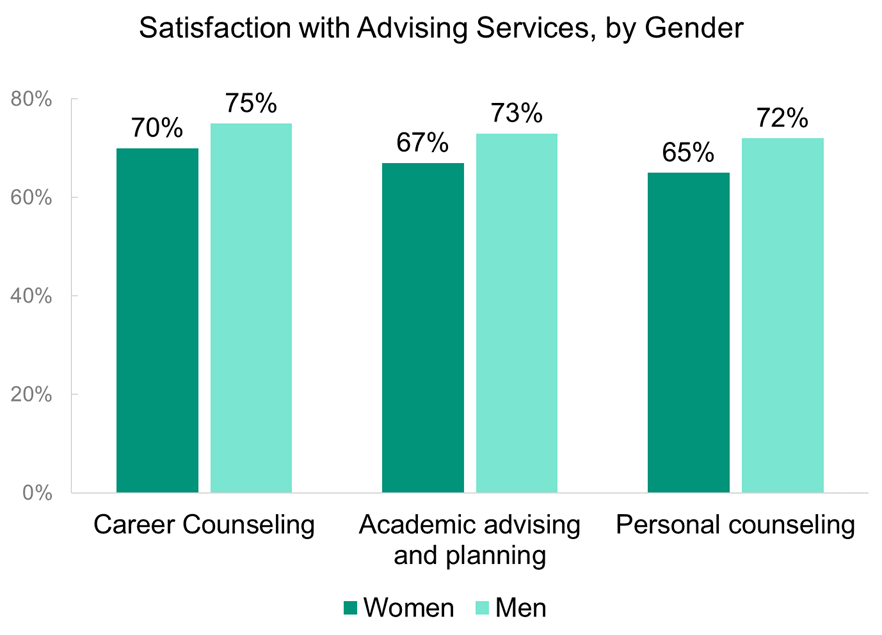

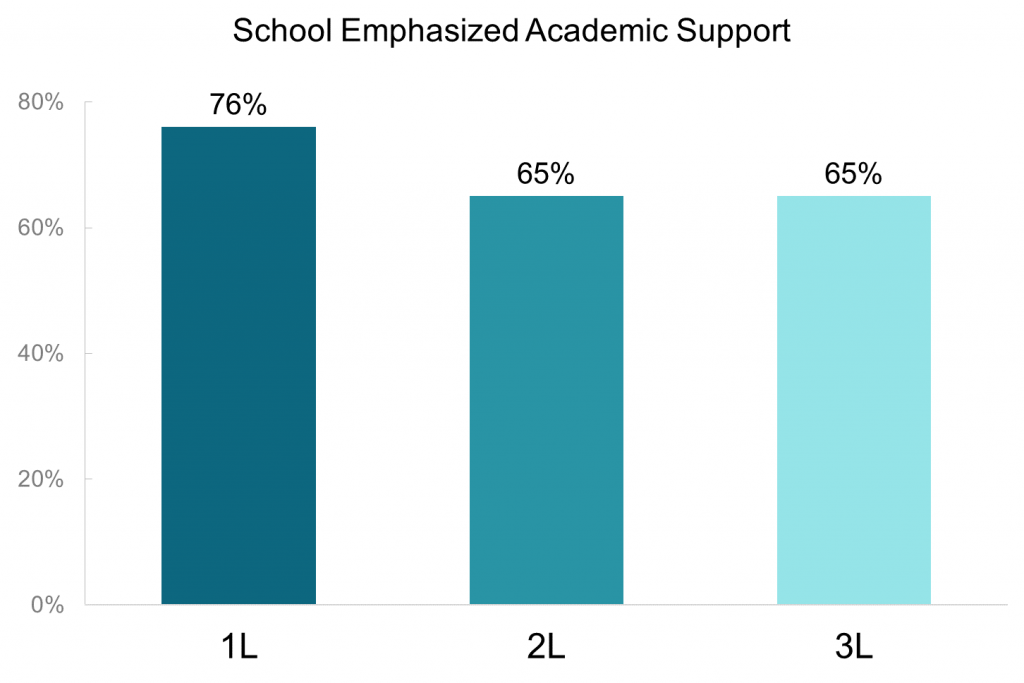

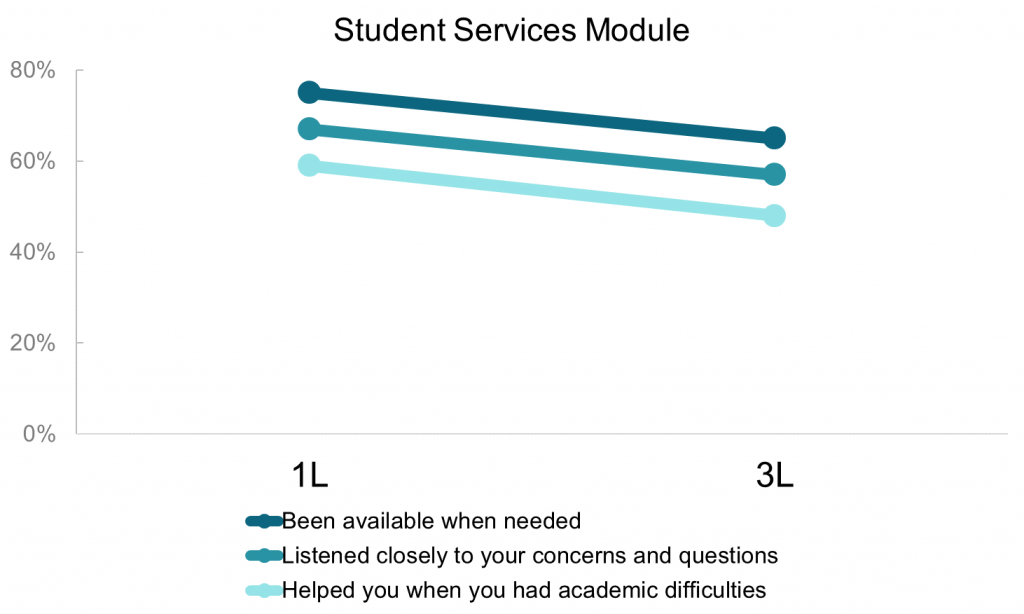

Interactions with academic support personnel drive whether a student would choose to attend the same law school again as well as overall satisfaction with their law school experience. Though students report positive relationships with administrative staff, satisfaction with advising services is less consistent and more varied across race/ethnicity, year in school, and gender. Sixty-nine percent of all respondents report that their law school provides the support they need to succeed academically, with higher perceptions of support among 1L students. Similarly, academic advising, career counseling, and job search help are key support services that students appreciate greatly when they begin law school, though they are more dissatisfied as graduation nears.

Annual Results 2018: Relationships Matter - Student-Faculty Interaction

Faculty, administrators, and classmates are key ingredients to law student success. These relationships serve as important ties to the law school and impact student satisfaction, sense of belonging, and academic and professional development. This year’s annual report explores relationships and examines the nuances of the impact they have on law students.

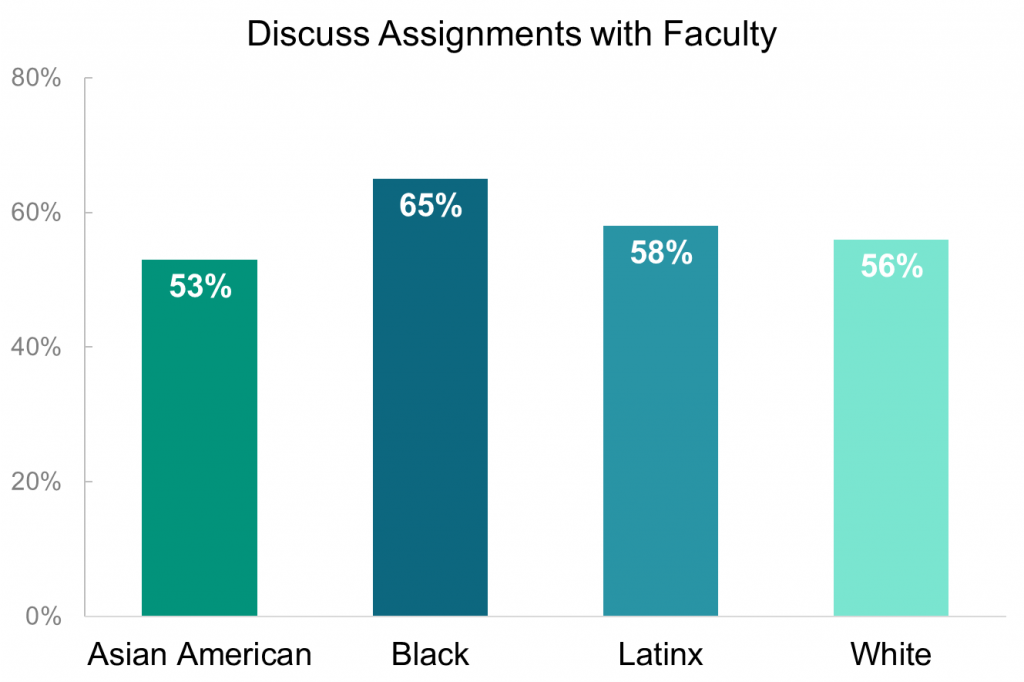

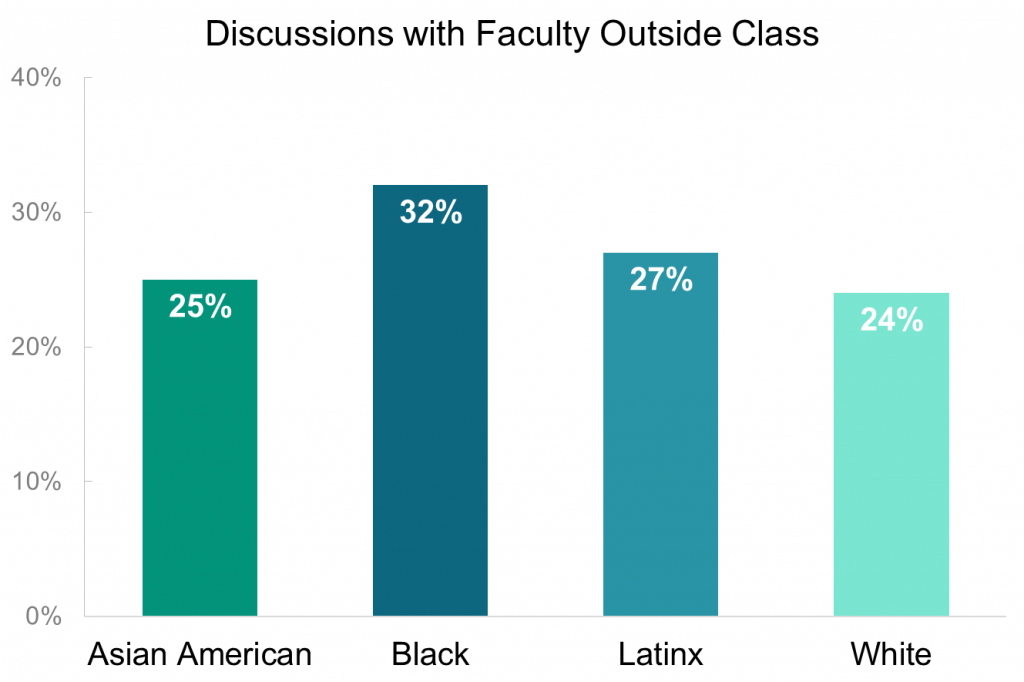

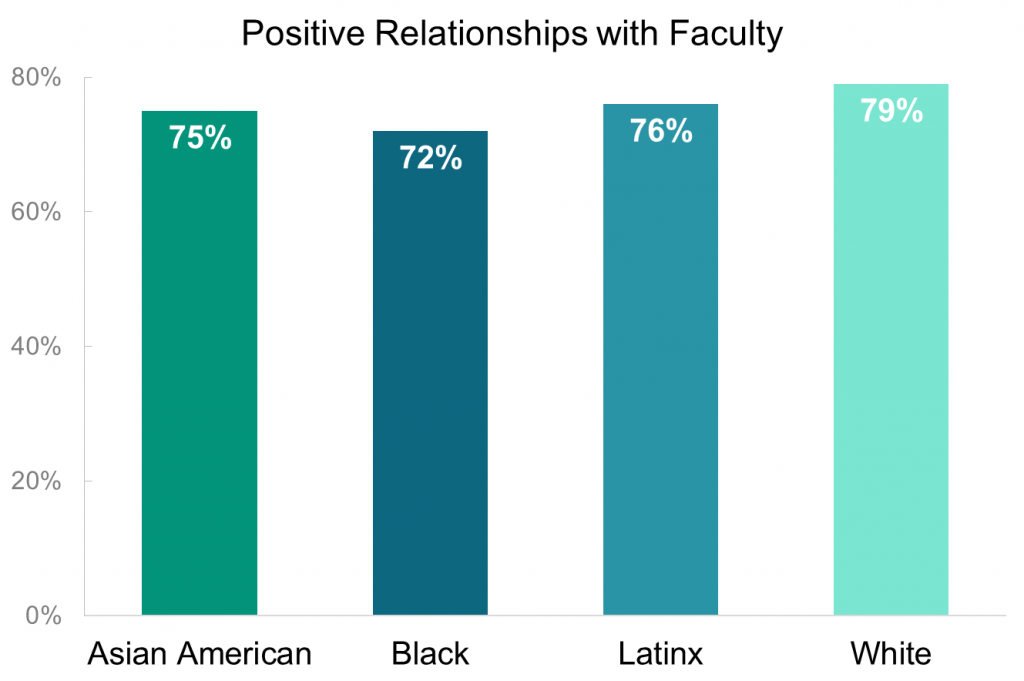

The vast majority of students (76%) report positive relationships with faculty, including interactions both in and out of the classroom. Meaningful interactions vary across student demographics, with notable race/ethnic differences. On multiple dimensions Black and Latinx students report more engagement and interaction with faculty than white and Asian American students. For instance, while a majority of all law students (57%) discuss assignments with faculty “often” or “very often,” 65% of Black students do so, the highest of any racial or ethnic group, followed by 58% of Latinx students, 56% of white students and 53% of Asian American students.

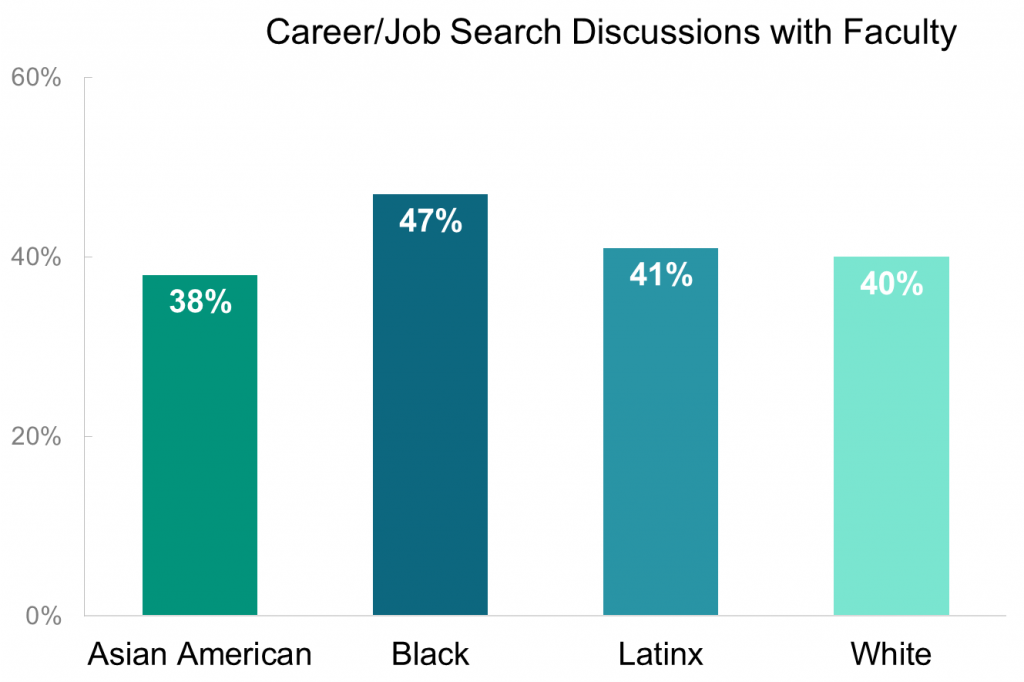

The pattern of Black and Latinx students enjoying higher rates of engagement with faculty persists across multiple dimensions. For example, Black students (47%) are more likely to discuss career or job search with faculty than Latinx (41%), white (40%), or Asian American (38%) students. Black and Latinx students are also more likely to talk with faculty outside of class. The vast majority of students find faculty available, helpful, and sympathetic. Interestingly, this sentiment does not directly track interaction with faculty, as a higher percentage of white students report favorable relationships with faculty than Black and Latinx students.

Preferences & Expectations for Employment After Law School by Student Debt Level

The newly released LSSSE 2017 Annual Results explore the relationship between students’ preferred and expected work settings post-graduation. Our most recent post looked at the settings in which male and female student prefer and expect to work. In the final post in this series, we examine how students with varying debt levels approach the question of where they prefer and expect to work after graduation.

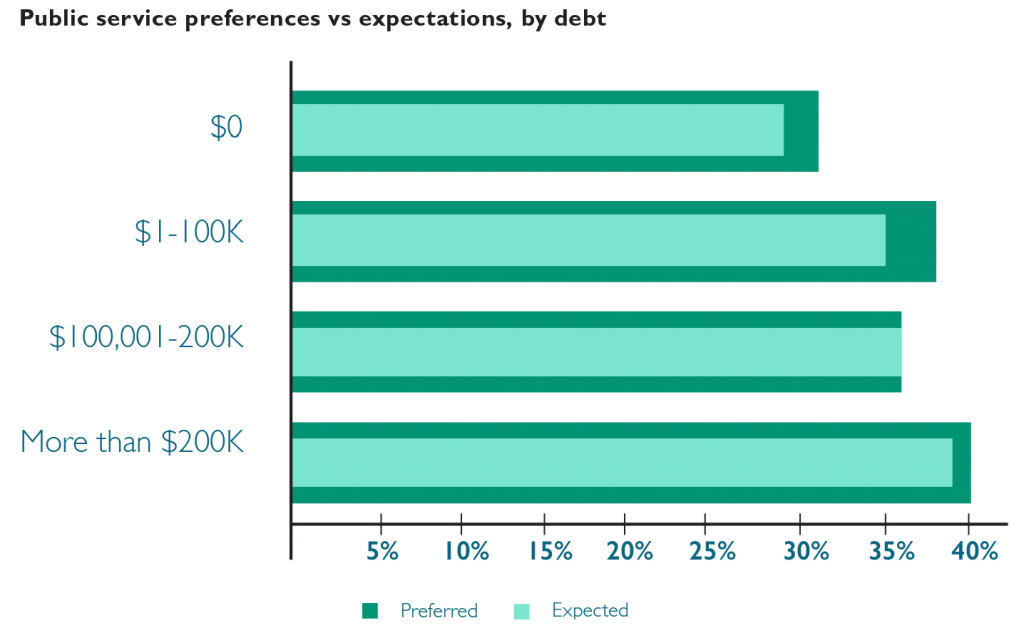

The role of student loan debt is important to consider in the context of student career preferences and expectations because earning potential varies tremendously across work settings within the legal profession. LSSSE asks respondents to estimate the amount of law school debt they expect to incur by graduation. Forty percent of respondents who expect to owe more than $200,000 prefer to work in a public service setting, the highest proportion of all student debt groupings. At 31%, respondents who expect no debt are least likely to prefer working in public service.

Expectations of working in public service decrease slightly relative to preferences for each of the student debt groups; but expectations of working in public service increase with expected debt. There is no evidence of high levels of expected debt prompting respondents who prefer public service settings to nonetheless expect to work in private settings (due to the prospect of higher pay). In fact, respondents who expect to owe more than $200,000 are most likely to prefer and expect to work in public service settings. Respondents expecting to owe more than $100,000 are mostly likely to prefer to work in private settings but expect to work in public service.

The motivation for pursuing legal work in one setting versus another is likely driven by a variety of factors rather than simple personal economics. The promise of programs like Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) may temper the negative financial ramifications of pursuing lower-paying public service careers among students in the highest student debt groupings. The relative popularity of public service work among Black and Latinx students coupled with the disproportionate student loan burden (pdf) shouldered by these students is likely another contributing factor to the trends we see here.

Preferences & Expectations for Employment After Law School by Gender

The newly released LSSSE 2017 Annual Results explore the relationship between students’ preferred and expected work settings post-graduation. Our most recent post in this series showed how these preferences and expectations are related to race and ethnicity. In this post, we will show how male and female law students differ in their preferences and expectations.

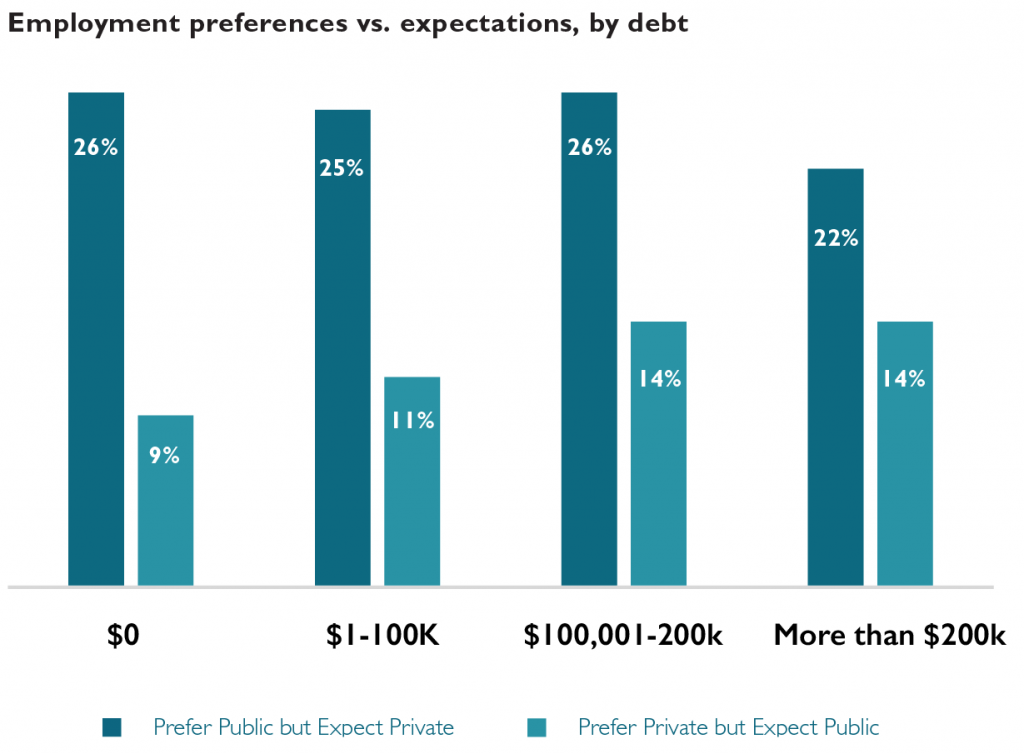

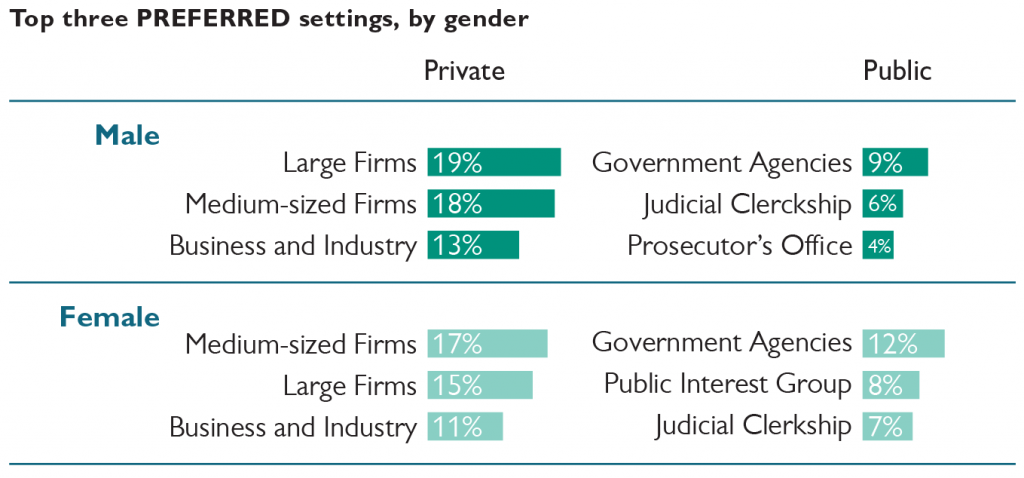

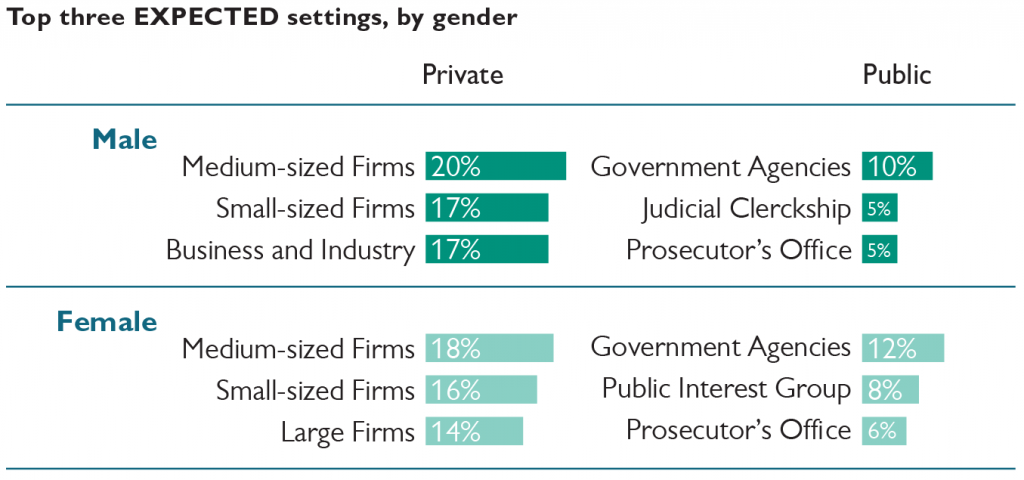

Seventy percent of male respondents indicate a preference for working in one of the private settings, compared to 59% of female respondents. Large firms are the most preferred among males. Medium-sized law firms are the most preferred private setting for female respondents. Government agencies are the most preferred public service setting for both groups, with female respondents more likely to indicate this preference.

Sixty-one percent of female respondents expect to work in the same type of setting they prefer; fifty-eight percent of males did so. Medium-sized law firms are the most commonly expected work setting for both groups, which for males was a shift from their preference for large firms. Government agencies are the most commonly expected public service setting for both groups.

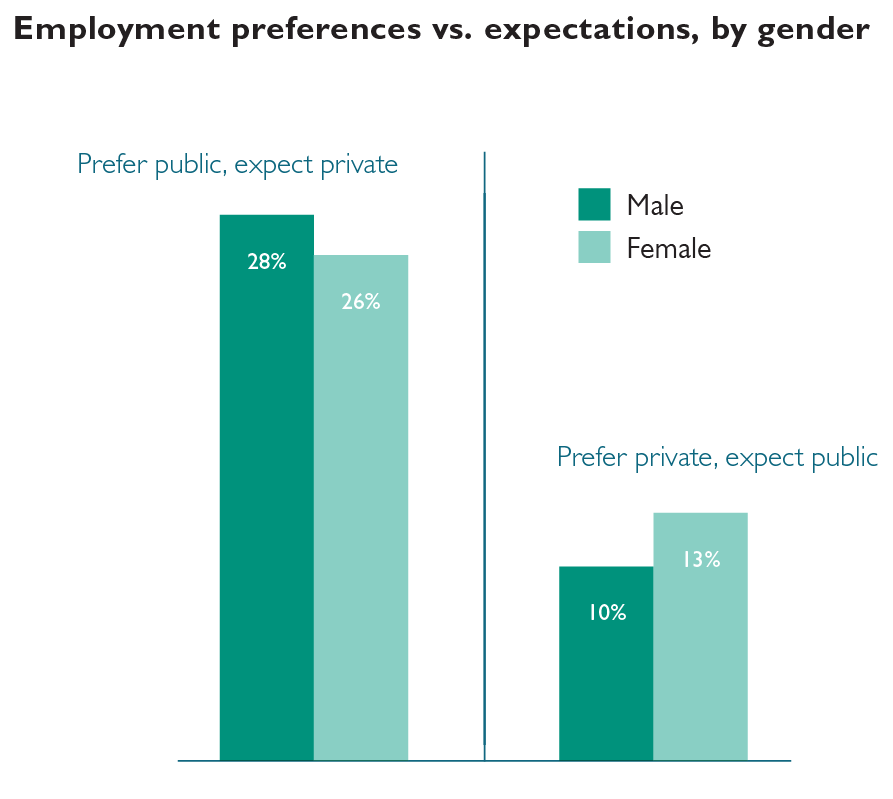

Male respondents are more likely than females to prefer to work in public service but expect to work in a private setting. Female respondents are more likely than males to prefer to work in a private setting but expect to work in public service.

Preferences & Expectations for Employment After Law School by Race and Ethnicity

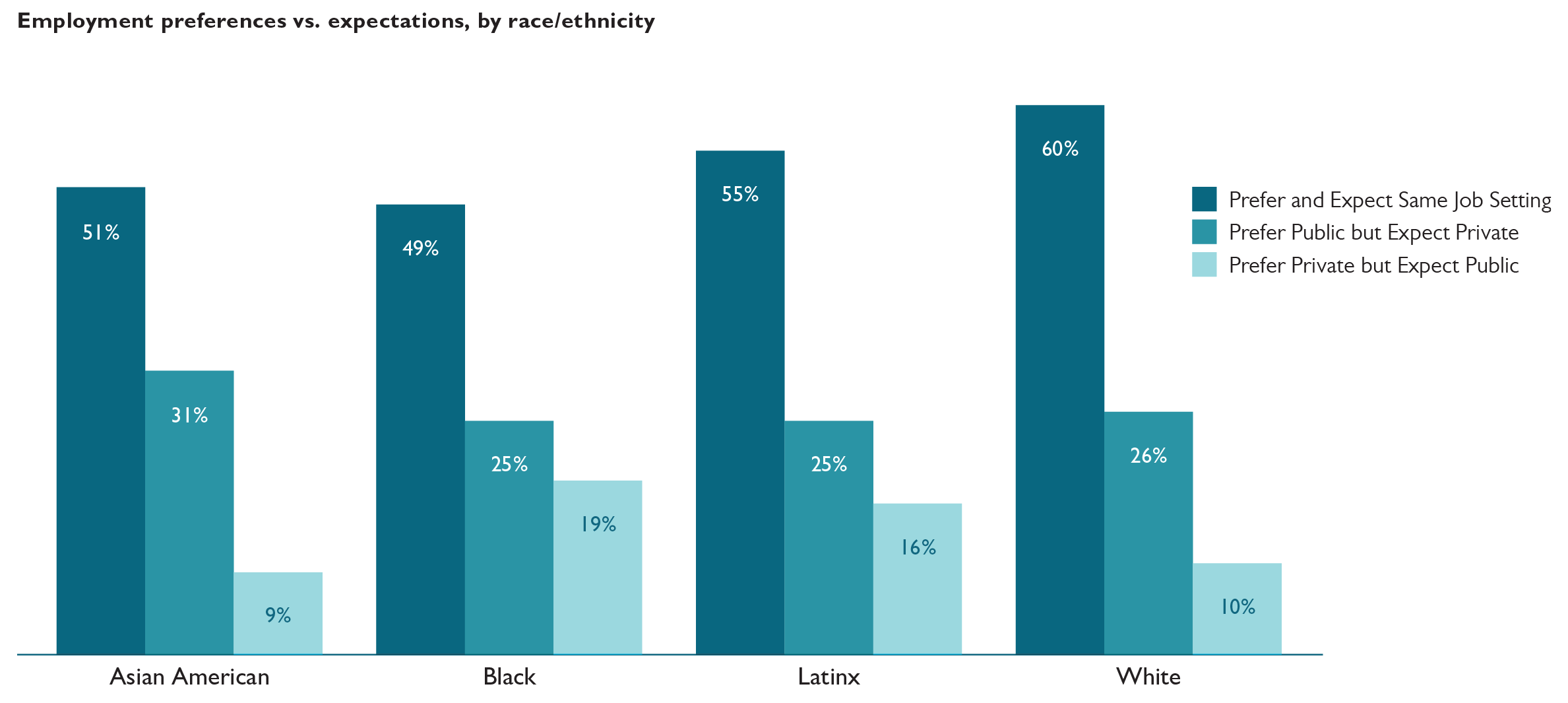

The newly released LSSSE 2017 Annual Results explore the relationship between students’ preferred and expected work settings post-graduation. Our most recent post in this series shared some general observations about the matches (and mismatches) between preferred and expected settings. In this post, we will share some insights into how these preferences and expectations are related to race and ethnicity.

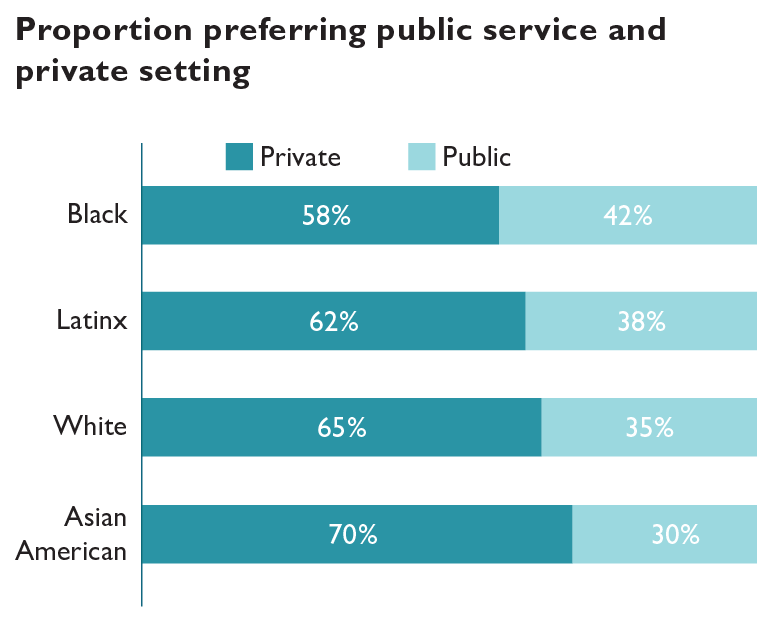

Overall, 64% of respondents prefer to work in the private sector. Almost 70% of Asian American respondents state a preference for working in a private setting, the largest proportion among the four racial and ethnic groups analyzed. Black respondents are most likely to prefer public service settings.

Black respondents are least likely to prefer and expect to work in the same individual setting, with less than half doing so, whereas White respondents (at 60%) are most likely. The proportion of respondents expecting to work in private settings increases among Asian American and White respondents, when compared to their preferences. Seventy-three percent of Asian American respondents expect to work in private settings, compared to 70% preferring to do so. Among White respondents, the proportion who expect to work in private settings is 68% compared to the 65% who prefer it. These two sets of proportions remain largely the same among Black and Latinx respondents.

Almost one-third of Asian American respondents who prefer public service settings expect to work in private settings, the highest proportion among all the racial and ethnic groups. Black respondents are most likely to prefer private settings but expect to work in public service.

Trends in Preferences & Expectations for Employment After Law School

The newly released LSSSE 2017 Annual Results explore the relationship between students’ preferred and expected work settings post-graduation. In a series of related blog posts, we will share tidbits of information about where law students hope to work, where they expect to work, and how these preferences and expectations vary by race and gender. In our final post, we will look at patterns in students’ preferred and expected work settings relative to their projected levels of student loan debt.

LSSSE asks respondents to identify the setting in which they would most prefer to work after graduation and the setting in which they most expect to work. Preferences can be seen as representing a respondent’s ideal outcome; expectations can be seen as representing perceptions of a realistic outcome. For both questions, respondents are asked to choose between sixteen answer options.

For purposes of much of the analyses in this report, the answer options were divided into two broad groups:

Public Service Settings

- Academic

- Government agency

- Judicial clerkship

- Legislative office

- Military

- Prosecutor’s office

- Public defender’s office

- Public interest group

Private Settings

- Accounting firm

- Business and industry

- Nonlegal organization

- Private firm – small (fewer than 10 attorneys)

- Private firm – medium (10-50 attorneys)

- Private firm – large (more than 50 attorneys)

- Solo practice

The “Other” response was removed from our analysis. The primary factor underlying the assignment of an answer option to one of the two groupings was whether a person working in that setting would likely qualify for Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF), which typically requires one to be employed in the government or non-profit sector. There is naturally some imprecision in the assignments.

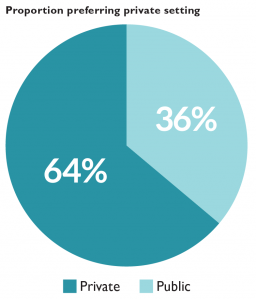

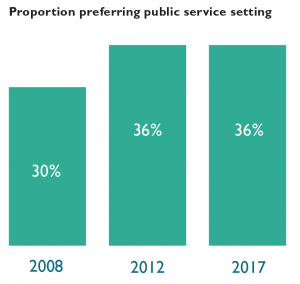

Sixty-four percent of respondents indicate a preference for working in one of the private settings, with the remaining 36% preferring public service. This proportion is unchanged from five survey administrations ago (2012) and higher than the 30% public service proportion ten administrations ago (2008).

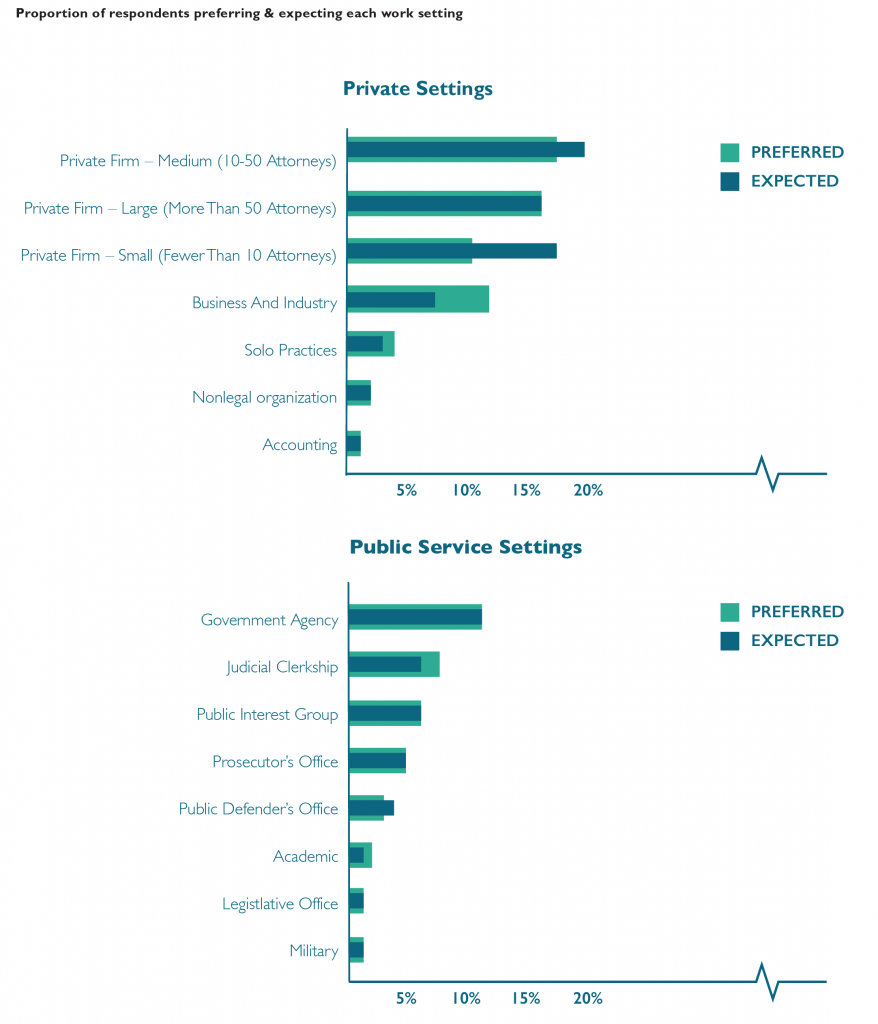

Seventeen percent of respondents would prefer to work in medium-sized law firms, making this category the most popular private setting and the most popular setting overall. Government agencies are the most popular public setting, with 11% of respondents indicating that preference. Medium-sized law firms are also the most commonly expected private work setting, accounting for 20% of respondents. Small law firms are the fourth most preferred private setting yet the second most common expected setting. Government agencies are the most commonly expected public service setting.

Forty-four percent of respondents indicate a different expected work setting than their preferred setting. Respondents who prefer to work in an academic setting are least likely to expect to work in that setting, with only about one-in-five matching preference with expectation. Respondents who prefer to work in large law firms or as prosecutors are most likely to also expect to work in those settings.

Forty-six percent of respondents who prefer one of the public service settings expect to work in a non-preferred setting, including one-quarter who expect to work in private settings instead. Forty-one percent of respondents who prefer one of the private settings expect to work in a different setting, but only 12% of students who prefer to work in a private setting expect to work in public service instead.