Focus on First-Generation Students, Part 2

In our last post, we shared some of the demographic characteristics of first-gen law students, which we define as law students who do not have at least one parent with a bachelor’s degree. In this post, we will dig deeper into the first-gen law student experience and how it differs from the experiences of non-first-gen law students.

Time Usage

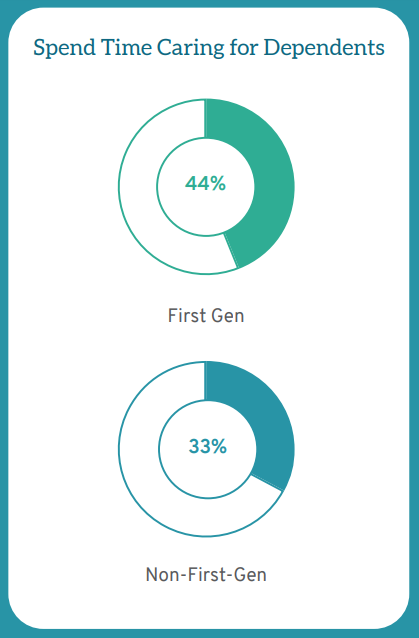

LSSSE asks students to estimate the average number of hours they spend each week engaging in activities that are directly and indirectly related to the educational experience. Time usage is important because it reflects students’ academic engagement and overall priorities. First-gen students are more likely to attend law school part-time, which suggests that they have complicated schedules with competing demands, rather than a sole focus on law school. LSSSE data show that high percentages of first-gen students have familial obligations as caretakers for dependents living in their household. Forty-four percent (44%) of first-gen students spend time caring for dependents, compared to 33% of non-first-gen students.

First-gen students are just as engaged as their non-first-gen peers in academic pursuits outside of class, despite the fact that they have more responsibilities competing for their time. First-gen students work with students and faculty on group projects at equal or greater levels relative to non-first-gen students. Roughly equal percentages of first-gen students (19%) and non-first-gen students (18%) report that they frequently work with faculty members on activities other than coursework (including committees, orientation, student life activities, etc.). Likewise, 33% of first-gen (and 31% of non-first-gen) students frequently work with classmates outside of class to prepare assignments. The diligence of first-gen students is particularly impressive given their personal obligations. One third (33%) of first-gen students always come to class fully prepared despite their family duties and work schedules, the same percentage as non-first-gen students (who tend to work less and have fewer familial obligations).

Satisfaction

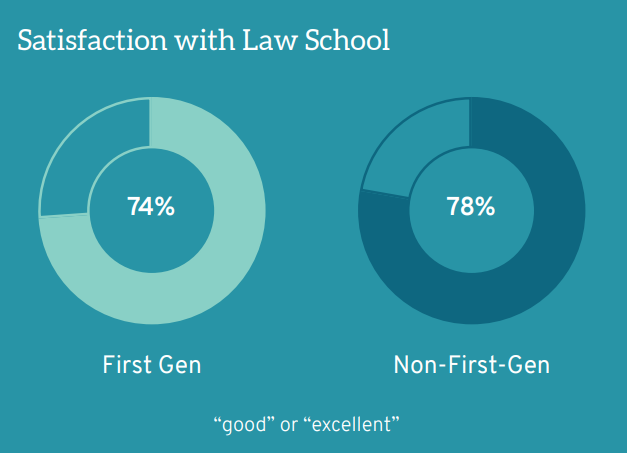

First-gen students, like law students overall, are overwhelmingly satisfied with their law school experience. Seventy-four percent (74%) of first-gen students evaluate the educational experience at their law school as “good” or “excellent,” similar to non-first-gen students (78%). Furthermore, 77% of first-gen (and 79% of non-first-gen) students report they would choose to attend the same law school again, with the benefit of hindsight. These trends are particularly noteworthy given the increased financial risks and other sacrifices made by first-gen students to attend law school.

First-gen students face unique challenges and responsibilities as they navigate legal education. Law schools should take the findings from this Annual Report, as well as their own school-specific LSSSE data, to craft targeted programs to support first-gen students. Better supporting them personally will free up time and resources for first-gen students to devote to not only academics, but other co-curricular pursuits so they are optimally placed to thrive as they enter the legal profession.

Focus on First-Generation Students, Part 1

Our next two blog posts will provide selected snippets from the LSSSE 2024 Annual Report: Focus on First-Generation Students. To read the entire report, please visit our website.

First-Gen Demographics

First-generation (first-gen) students are trailblazers for their families. They attend college without the guidance of a parent who has completed their own bachelor’s degree. Decades of research show that first-gen students overcome significant challenges simply to gain access to college and invest even more to persist until degree completion. First-gen students tend to enter higher education with fewer financial resources and less social and cultural capital than those who have at least one parent who completed a college degree. Although first-gen students have already drawn on their resiliency and determination to adapt to college life, law school brings its own cultural norms and ways of learning that are, again, likely to be unfamiliar.

Despite these expected challenges, few studies focus on the experiences of first-gen students in law school. In 2014, LSSSE was one of the first organizations in legal education to collect data on first-gen students by adding a survey question about parental education. The data LSSSE has collected shed light on how first-gen students engage with law school and how their experiences differ from those of their non-first-gen classmates.

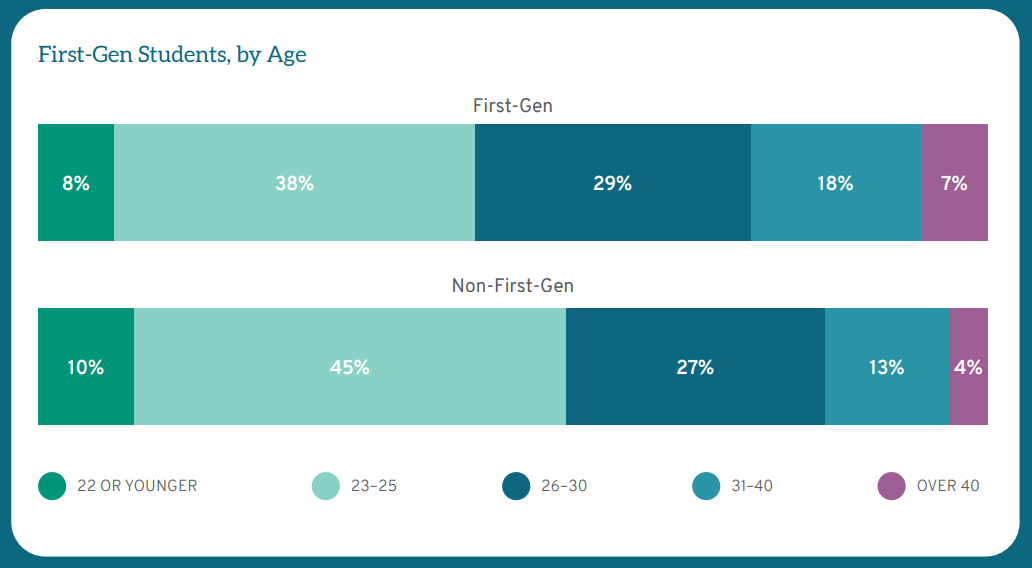

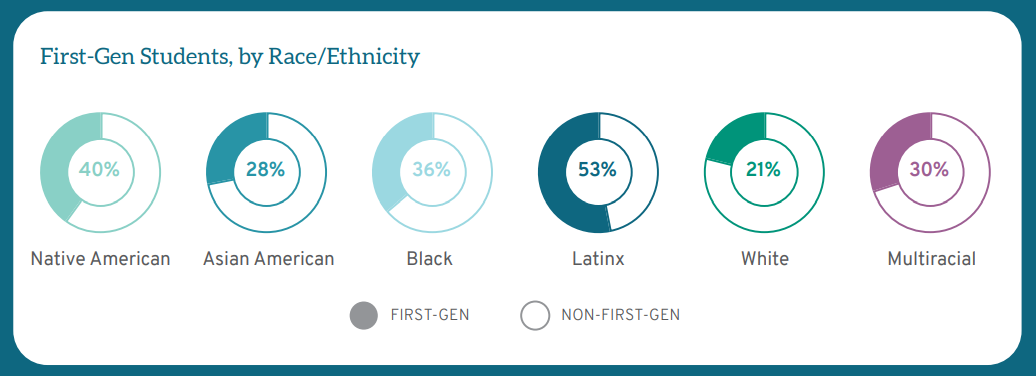

For LSSSE analyses, students who respond that neither parent received a bachelor’s degree or higher are considered first-gen students. First-gen students comprise over one-quarter (26%) of the LSSSE respondents. First-gen students tend to be different from non-first-gen students in important ways, including race, gender, age, and a full-time focus on law school. Students of color from every racial group are more likely than White students to be first-gen. For instance, 53% of Latinx respondents and 36% of Black respondents are first-gen, compared with 21% of White respondents. Twenty-eight percent (28%) of women are first-gen students compared to 24% of men. First-gen students also tend to be older, with 54% of first-gen students being over the age of 25 compared to 44% of non-first-gen students. Finally, while the vast majority of law students in the U.S. study on a full-time basis, first-gen students are more likely to study part-time by about 10 percentage points. Thus, in addition to their first-gen status, many of these students have other demographic differences from the average law student.

First-Gen Student Debt

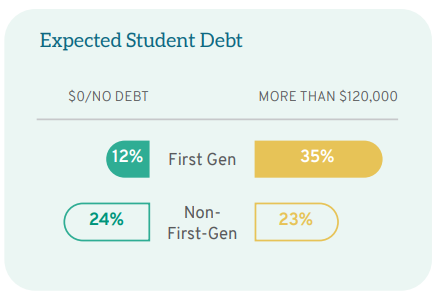

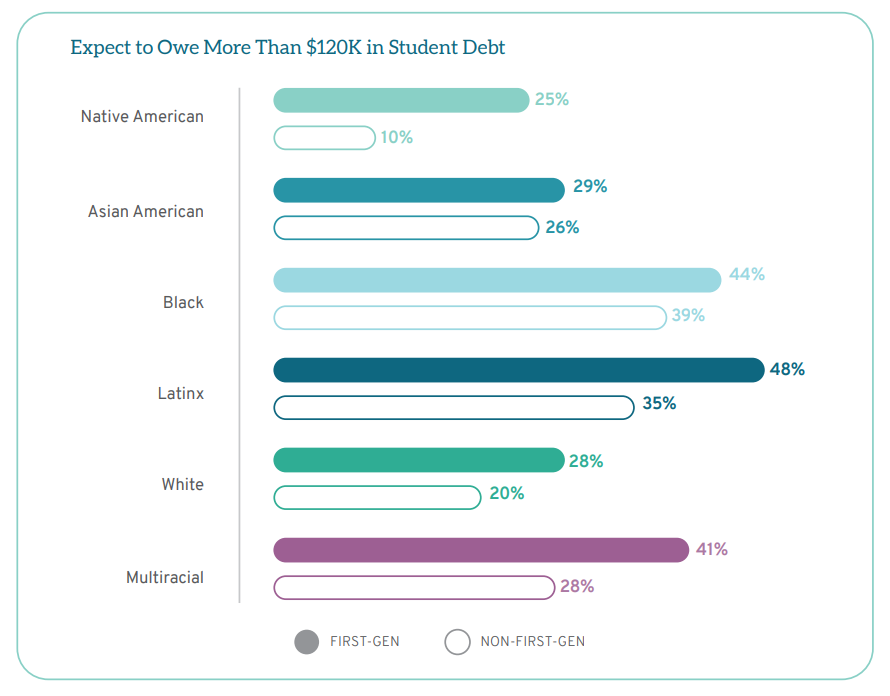

Parental education is often used as a proxy for socioeconomic status. A college degree has a significant positive impact on salary and career earnings over a lifetime. On average, first-gen students come from families that earn less than the families of students with a parent who completed college. Because first-gen students enter law school with lower undergraduate GPA and LSAT scores and because higher LSAT scores result in greater success with scholarships, first-gen students are less likely to be awarded merit scholarships in law school. As a result, first-gen students rely on student loans to a greater extent than their classmates. For instance, 24% of non-first-gen students anticipate graduating with no law school debt compared to only 12% of first-gen students. Conversely, roughly one-quarter (23%) of non-first-gen students expect to graduate with more than $120,000 in student debt compared to over one-third (35%) of first-gen students. Students from the same racial background nevertheless have significant debt differentials based on whether they are first-gen students, with first-gen students of color borrowing at particularly high levels.

First-gen students differ from their non-first-gen classmates in meaningful ways. First-gen students typically are older students, many have caretaking responsibilities, and they are more likely to come from families with fewer financial resources, necessitating working while in school. Because of these differences, first-gen students bring valuable life experiences and diverse perspectives to classroom conversations. Once they complete law school, they are also equipped to bring the fruits of their legal education back to their communities. The hard work and determination that first-gen students bring to law school is nonetheless coupled with higher levels of debt than their non-first-generation peers. This creates an additional burden not only during law school but as they choose their first jobs as lawyers and continue their legal careers.

In our next blog post, we will examine how first-gen law students use their time and the degree to which they engage with different aspects of the law school experience.

Success with Online Education: Classroom Environment

Our last post shared some general findings about online learning from our 2022 Annual Results, Success with Online Education (pdf). In this post, we will share evidence that online classrooms appear to encourage a more diverse cross-section of students to participate in class discussions. We will also share reassuring signs that online law students are learning as much as their in-person counterparts.

Online discussions feature diverse voices

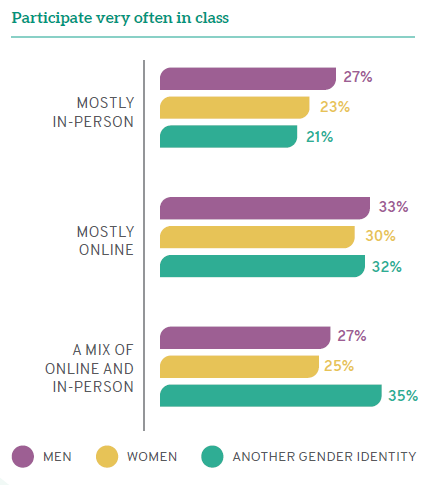

Online classes excel at inviting participation from a broader range of students than in-person classes. Men are equally likely to participate in class discussion and ask questions “often” or “very often” whether participating in person (60%) or online (61%). However, women taking mostly online courses are more likely to engage in class “often” or “very often” (58%) compared to women taking mostly in-person courses (53%). In fact, online courses appear to encourage all students to engage more intensely with class discussion. One quarter of students (25%) who take primarily in-person classes participate “very often” compared to 31% of students taking mostly online classes. There is a marked gender difference, with 23% of women participating “very often” in person but a full 30% participating “very often” online, and only 21% of those with another gender identity participating “very often” in person while 32% do so online. The online environment–perhaps because of the mechanisms for turn-taking or because it is more comfortable for students to volunteer– invites more voices to engage in the conversation.

Online students are learning as much as in-person students

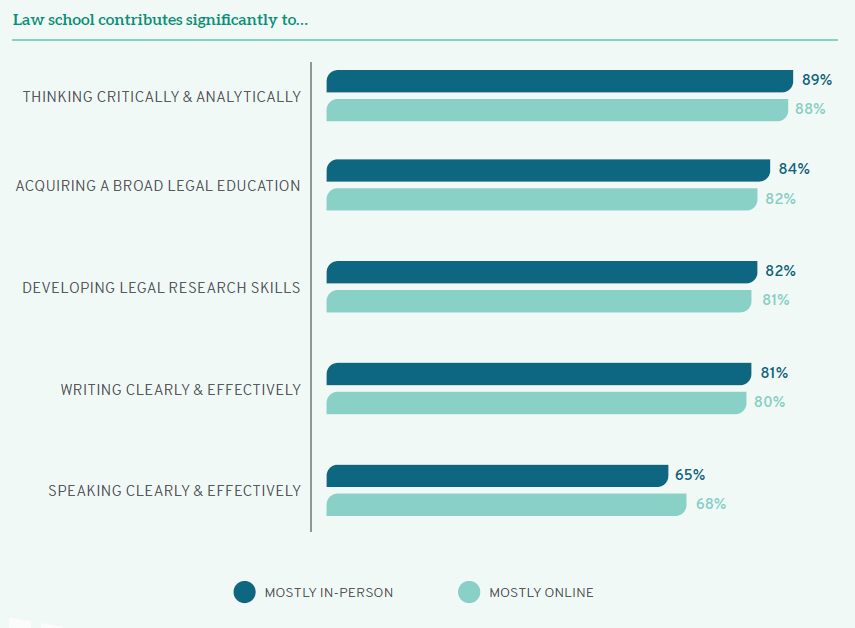

Regardless of how they attend classes, most students are confident that they are developing crucial legal skills. Nearly 90% of online and in-person students are learning to think critically and analytically. More than four out of five online and in-person students say they are acquiring a broad legal education (82% and 84%, respectively) and developing legal research skills (81% and 82%, respectively). Interestingly, online students are more likely to be developing the ability to speak clearly and effectively, perhaps because online courses invite more participation from a diverse range of students. Thus, law school classes do not lose their intellectual rigor when they are offered in an online format.

Online law school classes can be highly successful and well-received by students. Many students who take most of their classes online are as satisfied—and sometimes more satisfied—than their peers who attend classes primarily in person. Furthermore, law students who attend classes via either modality are equally likely to feel confident that they are learning important skills that will help them succeed as legal professionals. Although the law school experience is unlikely to be primarily online again, the accelerated transition to offering online courses that occurred due to COVID-19 shows that the online law school experience can be as successful, enriching, and satisfying as the traditional law school curriculum.

Success with Online Education: Relationships

The latest LSSSE Annual Results, Success with Online Education (pdf), focuses on the largely positive online learning experiment that law schools embarked upon due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This week and next week we will share selected snippets from the results. In this post we will describe how the switch to online learning impacted relationships among law students, law faculty, and administrators.

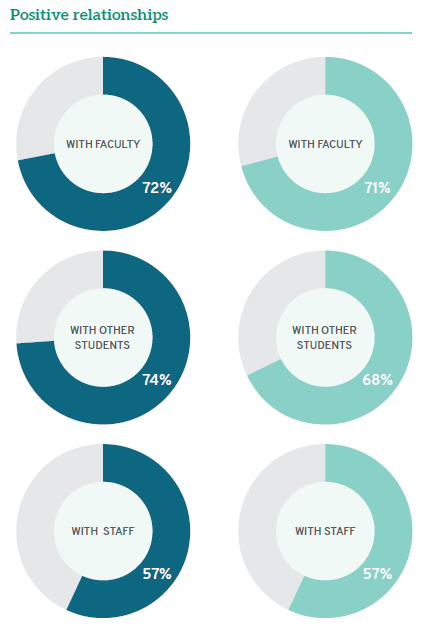

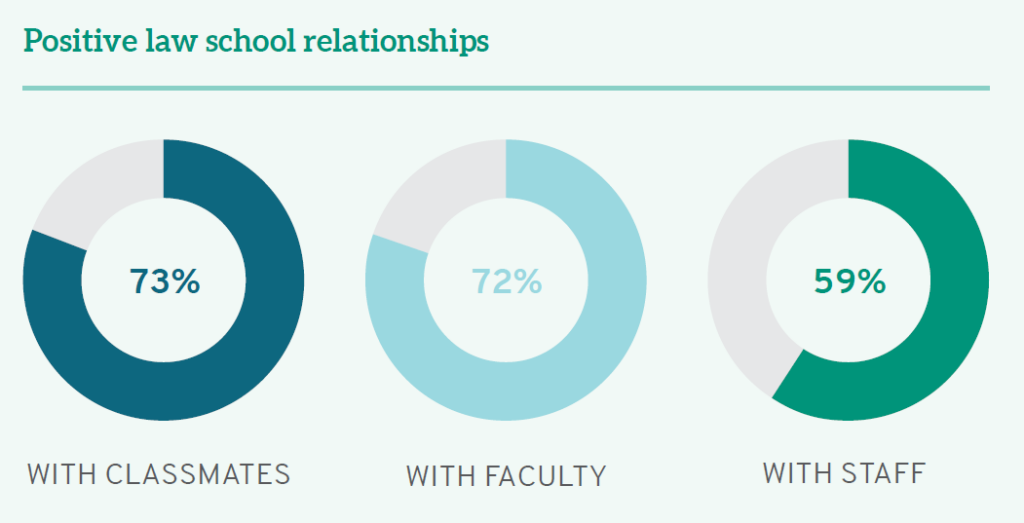

LSSSE data confirm other research showing how law school faculty have invested an enormous amount of energy and effort to connect with students, regardless of instructional modality. A full 72% of students taking mostly in-person classes have strong relationships with faculty (5 or higher on a 7-point scale), and 71% of mostly online students feel the same way. Students remain highly engaged with faculty in an online environment.

Online students and in-person students are equally likely to have positive relationships with administrative staff. A little over half (57%) of each group rate their relationships with their law school’s administrators a 5 or higher on a 7-point scale. Career services-oriented staff could consider using these relationships to bring more targeted career guidance to online students to narrow the gap in career preparedness between online students and in-person students. However, the relatively low percentage of both in-person and online students who have strong relationships with staff is a point of concern that should be addressed to better support law student development.

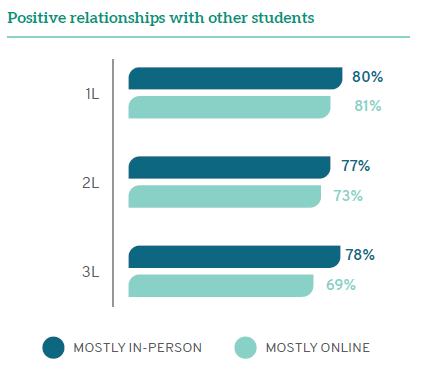

Despite similarly positive relationships with professors, students in mostly online classes are less likely than others to have strong relationships with each other. Only 68% of online students rate their relationships with their classmates positively, compared to nearly three-quarters (74%) of in-person students. There is again a disparity across class years, with 1Ls having similarly positive peer relationships regardless of mode of attendance and online 3Ls being much less likely to enjoy strong relationships with their peers than 3Ls attending in person. There may be a loss of social connections among online students because of a lack of the sort of incidental contact that builds relationships over time.

Next week we will discuss the learning experience in the virtual classroom. For the complete story, you can view the entire report on our website.

Part 1: The COVID Crisis in Legal Education: Impact on Core Mission and Enriching Experiences

Because LSSSE has been annually administered since 2004, the survey was well-positioned to capture shifts in students’ perceptions and behaviors during the uniquely challenging 2020-2021 academic year. Our 2021 Annual Results, The COVID Crisis in Legal Education (pdf) draws from the core survey and two new modules (“Coping with COVID” and “Experiences with Online Learning”) to identify key struggles and successes of legal education during a period marked by uncertainty and disruption.

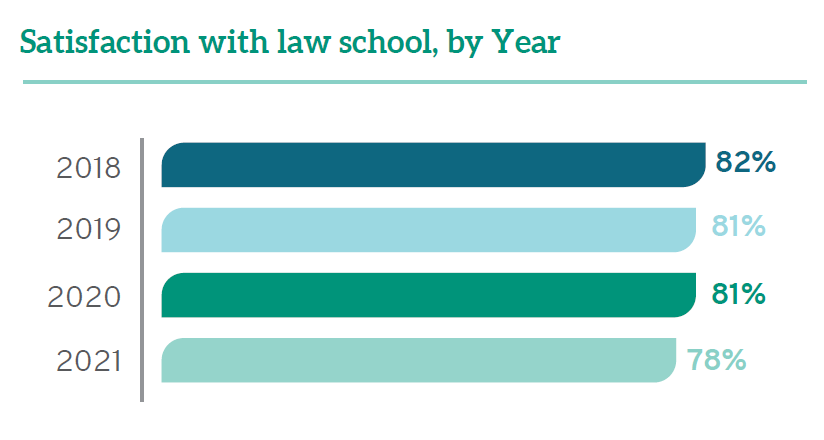

In the midst of a challenging year, some positives emerge from the data. Overall satisfaction remained high throughout legal education and comparable to past years. A full 78% of students in 2021 rated their entire educational experience in law school as “good” or “excellent,” which is similar to rates from recent years (82% in 2018, and 81% in 2019 and 2020). This is a testament to the significant efforts of faculty, staff, and administrators who pivoted to meet student needs as well as to the resiliency of the students themselves.

Nevertheless, the ability to forge and foster relationships has been especially difficult during the pandemic, which is borne out in the data. The percentage of students reporting positive relationships with staff dropped from 68% in 2018 to 59% in 2021—the lowest percentage recorded since LSSSE began collecting data on student-staff interactions in 2004. During those same years, positive student relationships with faculty and fellow students dropped just slightly from 76% to 72% and 76% to 73%, respectively. A full 93% of students appreciated that their law professors showed “care and concern for students” as the pandemic raged around them. First-year students were less likely to report positive relationships than 2Ls and 3Ls—likely because upper-class students could build on foundations they had cemented pre-COVID while 1Ls were attempting to start relationships from scratch in the midst of the pandemic.

The core of legal education remains relatively unchanged. Every year from 2018 to 2021, 85% of students have acknowledged that their schools contributed “quite a bit” or “very much” to their ability to acquire a broad legal education. There were also minimal changes this year compared to years past with regard to students developing legal research skills (80- 83%) and learning effectively on their own (81-82%).

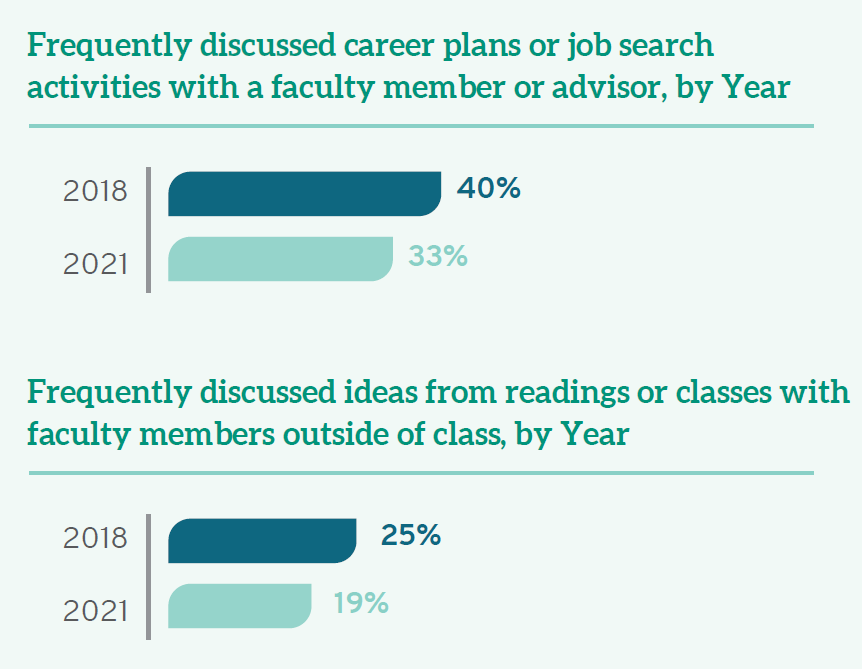

Yet the intangibles of legal education were significantly affected by COVID-19, with potential negative consequences on the professional competency of these future lawyers. A full 90% of students noted that COVID interfered with their ability to participate in special learning opportunities, including study abroad, internships, and other field placements. While discussions about course assignments and faculty feedback on academic performance remained constant, just one-third (33%) of all law students found frequent occasions to talk with faculty members or other advisors about career plans or the job search process (down from 40% in 2018), and only 19% frequently discussed ideas from readings or classes with faculty members outside of class (down from 25% in 2018). There were also fewer opportunities for students to work with faculty members on activities other than coursework.

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted nearly all aspects of life, and law school is no exception. Although law schools did their best to continue on with the education of the next generation of lawyers, there were still marked decreases in student engagement, particularly in building relationships and gaining experience outside the classroom. In our next post, we will explore the areas in which law students struggled the most in their lives and show how the pandemic disproportionately impacted those students who were already the most vulnerable.

Annual Results 2020 Diversity & Exclusion: Diversity Skills

This year for the first time, LSSSE introduced a set of questions focused on diversity and inclusion that supplement related questions from the primary survey. The Diversity and Inclusiveness Module examines environments, processes, and activities that reflect the engagement and validation of cultural diversity and promote greater understanding of societal differences. The 2020 LSSSE Annual Results Diversity & Exclusion report presents data about how diversity in law school can prepare students for the effective practice of law upon graduation. In our final post in this series, we will explore how law schools can teach skills to equip students to interact with people from different backgrounds.

Schools have a responsibility to not only admit and provide the resources to enroll a diverse class of students, but to impart the skills these students will need to be effective lawyers. Increasingly, the practice of law requires sensitivity to issues of race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status. Law schools can empower students first by encouraging them to reflect on their own identities, and then supplying coursework on issues of privilege, diversity, and equity; while it is important for students to learn about anti-discrimination and anti-harassment, law schools should also equip them with the tools they will need to fight these social problems as attorneys and civic leaders.

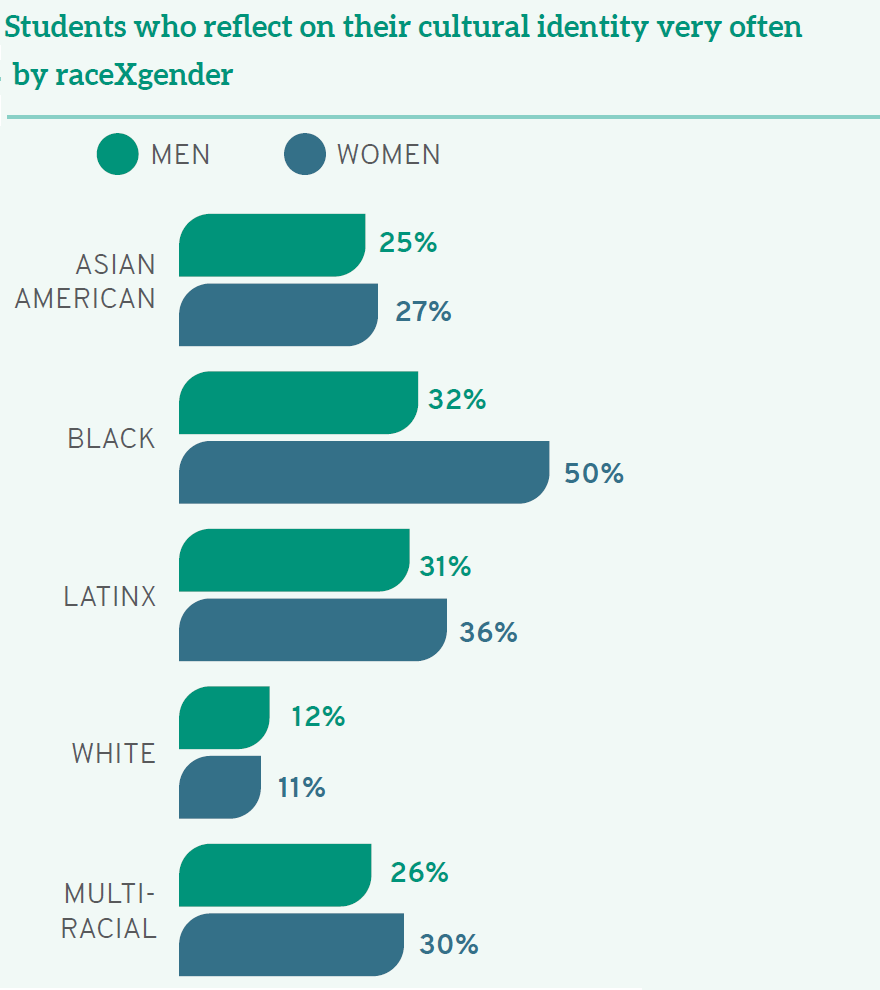

Yet schools are, by and large, not preparing law students to meet these challenges and succeed as leaders. When students were asked how frequently they reflect on their own cultural identity, only 12% of White students do so "very often," compared to 50% of Native American students, 44% of Black students, and 34% of Latinx students. Even more alarming, over a quarter (26%) of White students never reflect on their cultural identity during law school. When we consider the intersection of raceXgender, an even more troubling picture emerges. A full 28% of White men and 25% of White women in law school never reflect on their cultural identity, compared to the 50% of Black women who do so "very often."

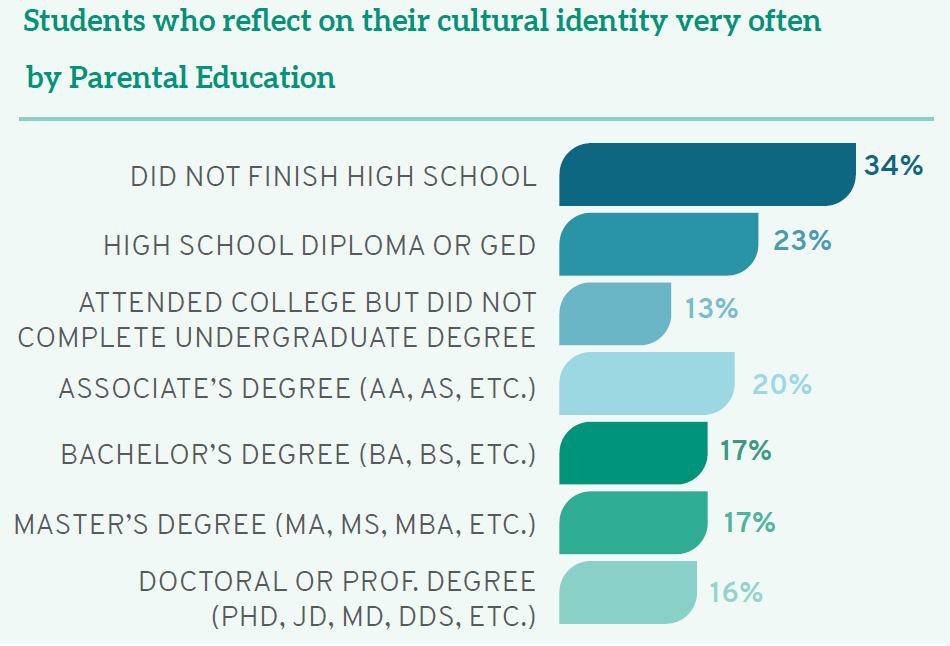

Students whose parents have less formal education are also more likely to reflect on their cultural identity, including 34% of those whose parents did not finish high school as compared to 16% of those who have a parent with a doctoral or professional degree. In sum, students with racial, gender, or class privilege are less likely to reflect on the benefits associated with their identity.

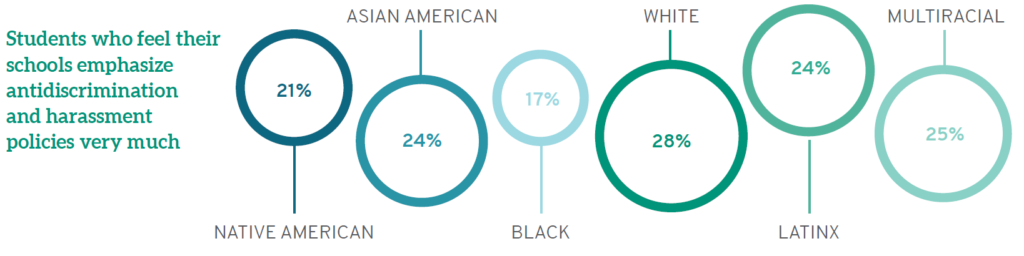

Even without self-reflection, students can nevertheless gather information about anti-discrimination and harassment policies. LSSSE data show that while White students see their schools as prioritizing this information, students of color do not agree at the same high levels. Similarly, men (31%) are more likely than women (23%) and those with another gender identity (11%) to believe their schools strongly emphasize information about anti-discrimination and harassment. Considering raceXgender, a full 27% of Black women see their schools as doing "very little" to share information on anti-discrimination and harassment, while 32% of White men believe their schools do "very much" in this regard.

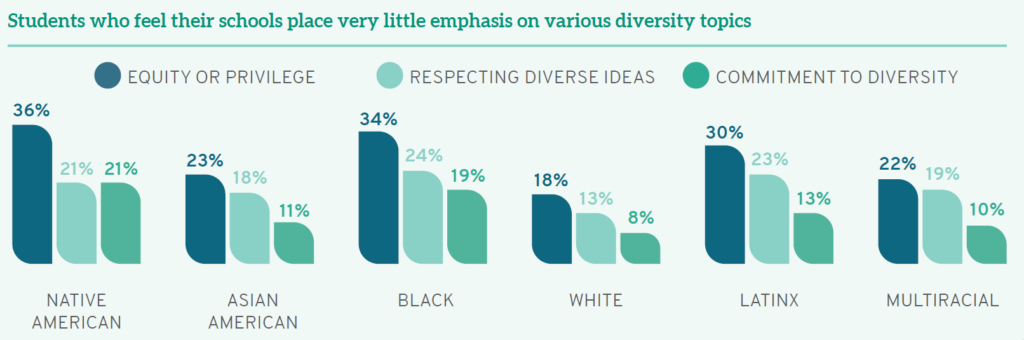

Equally troubling, students from different backgrounds perceive institutional emphasis of various diversity-related topics in starkly divergent ways. Although White students believe that their schools emphasize issues of equity or privilege, respecting the expression of diverse ideas, and a broad commitment to diversity, students of color are less likely to agree. Students of color—including those who are Black, Latinx, Asian American, Native American, and multiracial—frequently note and appreciate assignments or discussions of race/ ethnicity and other identity-related topics in the classroom; yet they are more likely than their White peers to report that schools place “very little” emphasis on diversity issues. Women are similarly more likely than men to believe their schools do “very little” to emphasize diversity in coursework. Furthermore, higher percentages of Black women report “very little” emphasis on equity or privilege (36%), respecting diverse perspectives (27%), and an institutional commitment to diversity (21%)— compared to high percentages of White men who believe their schools are doing “very much” in all three arenas (20%, 24%, and 34%, respectively). First-gen students are also more likely than their classmates whose parents completed college to note “very little” diversity coursework. Synthesizing these data, students who are traditionally underrepresented and marginalized—arguably the students who have the most personal experience with issues of diversity—see their schools as doing less to promote diversity and inclusion than those who are privileged in terms of their race/ethnicity, gender, and parental education.

As part of a broad curriculum that sets up students for their future practice, law schools should teach students diversity skills—a set of skills that facilitate success in our increasingly globalized society, ranging from personal reflection to the tangible tools lawyers can use to combat discrimination. Law schools that succeed at these diversity-related endeavors will be preparing our nation’s newest lawyers to meet the full range of challenges ahead.

Annual Results 2020 Diversity & Exclusion: Sense of Belonging

This year for the first time, LSSSE introduced a set of questions focused on diversity and inclusion that supplement related questions from the primary survey. The Diversity and Inclusiveness Module examines environments, processes, and activities that reflect the engagement and validation of cultural diversity and promote greater understanding of societal differences. The 2020 LSSSE Annual Results Diversity & Exclusion report presents data about how diversity in law school can prepare students for the effective practice of law upon graduation. In this post, we explore how sense of belonging at law school varies among students from different backgrounds.

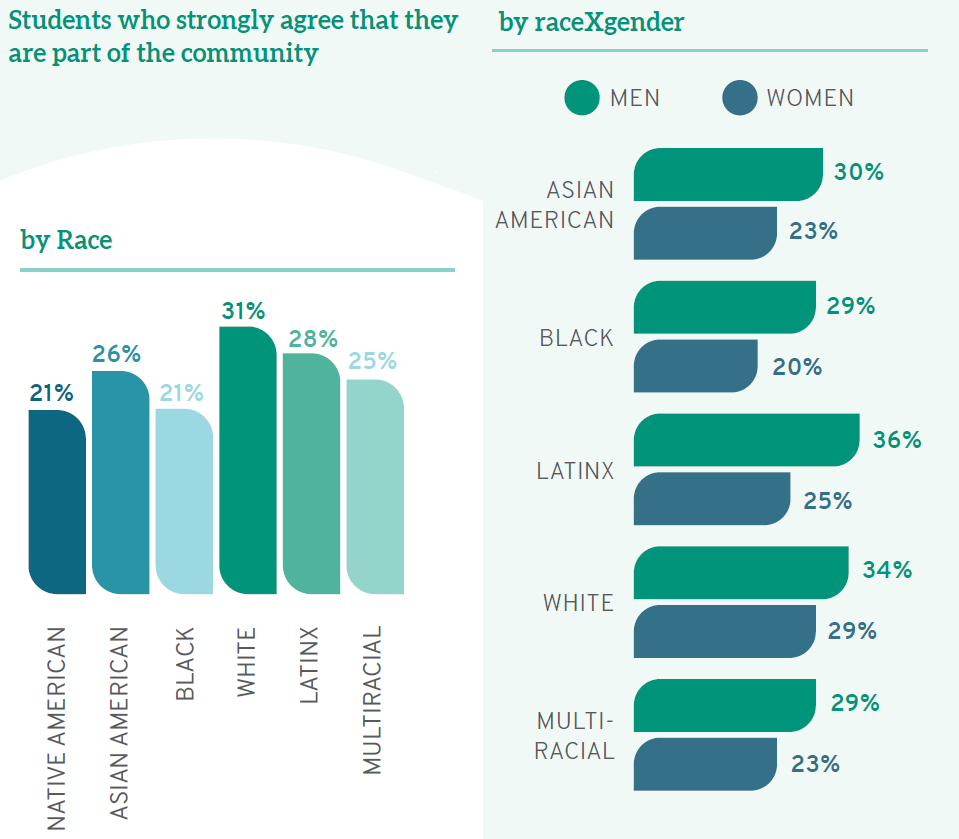

Scholarly research indicates that students who have a strong sense of belonging at their schools are more likely to succeed.1 Generally, belonging refers to feeling like part of the institutional community, fitting in, and being comfortable on campus.2 Using a number of separate indicators, LSSSE data on diversity and inclusiveness show that White students are more likely to have a strong sense of belonging than their classmates of color. For instance, when asked whether they feel they are "part of the community at this institution," a full 31% of White students strongly agree—though lower percentages of students of color do, including only 21% of Native American and Black students. Even more problematic when considering the importance of building an inclusive community: women of color are more likely than men from their same racial/ethnic backgrounds to feel that they are not part of the campus community—including a whopping 34% of Black women law students nationwide. First-gen students also deserve greater support, as only 23% "strongly agree" that they feel like part of the community at their law school, compared to 31% of students whose parents have at least a bachelor’s degree.

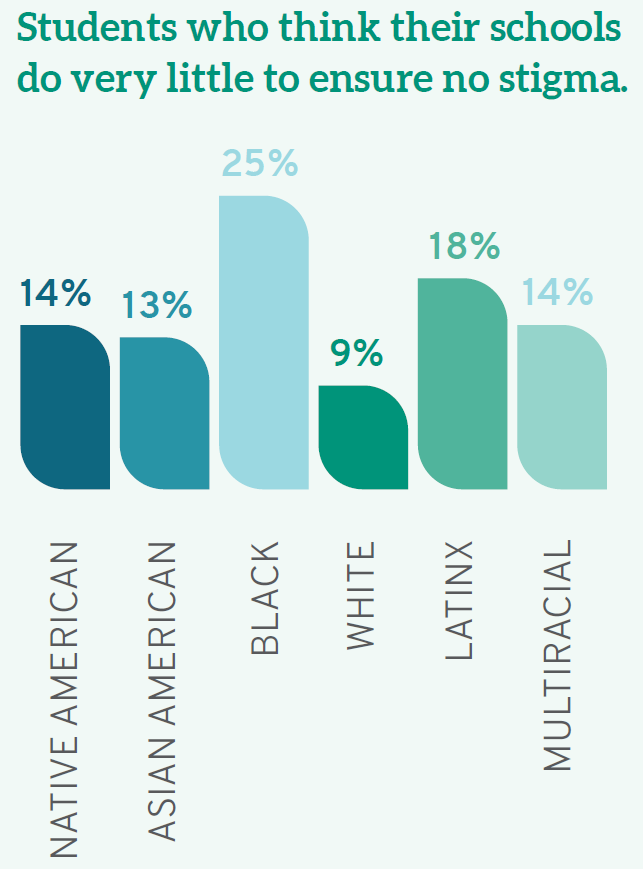

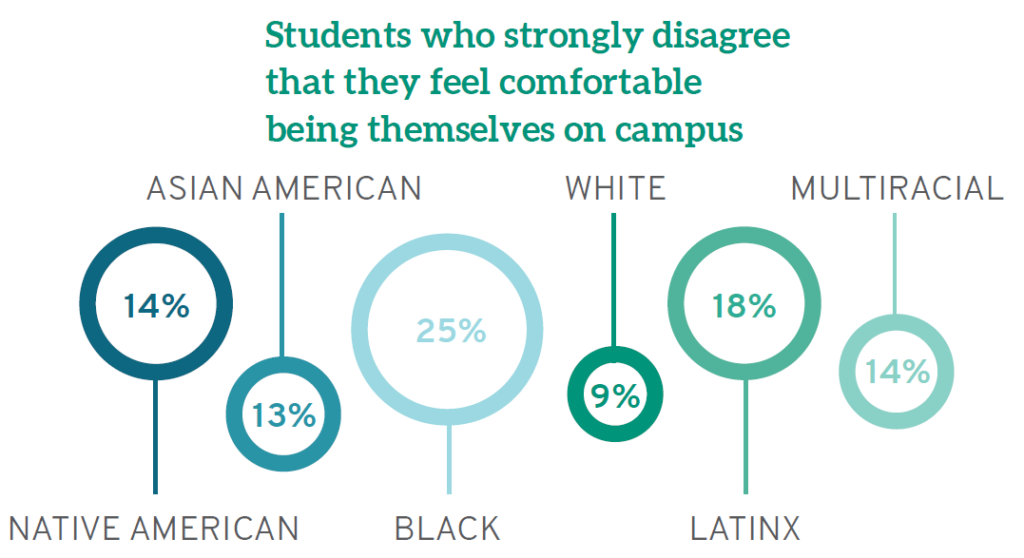

Students of color are also more likely than their White classmates to think their schools do "very little" to ensure students are not stigmatized based on various identity characteristics, including race/ethnicity, gender, religion, and sexual orientation. While only 9.3% of White students agree, 14% of Native Americans, 18% of Latinx students, and a full quarter (25%) of Black students believe their schools do "very little" to emphasize that students are not stigmatized based on identity. Similarly, 11% of heterosexual students think their schools do only "very little" to avoid identity-based stigma; conversely, 20% of gay students, 16% of lesbians, 15% of bisexual students, and 19% of those who identify as another sexual orientation see their schools as doing "very little" in this regard. Taken together, these findings suggest that those most likely to suffer stigma are also those most likely to think their schools do very little to protect them.

White students are also more likely than those from other backgrounds to be comfortable being themselves on campus, with only 12% noting they are not. Yet one out of every five (21%) law students who is Native American, Black, or Latinx notes that they do not "feel comfortable being myself at this institution."

There are also disturbing disparities when considering parental education—a strong proxy for family socioeconomic status. Being comfortable on campus increases almost in lockstep with increases in parental education; a full 32% of law students whose parents did not finish high school are uncomfortable being themselves on campus, compared to just 12% of those who have a parent with a doctoral or professional degree.

The overarching theme from this report is that those who are most affected by policies involving diversity—the very students who are underrepresented, marginalized, and non-traditional participants in legal education—are the least satisfied with diversity efforts on campuses nationwide. Nontraditional students remain marginalized on campus, left out of the community, devalued, and underappreciated. The solution is clear: institutions should place greater emphasis on valuing students from all backgrounds, creating an inclusive community, and integrating diversity into the curriculum. With that foundation, law schools can prepare students to interact in meaningful ways with diverse clientele, to first recognize and then resist instances of discrimination or harassment, and to meet the many challenges they will confront in their roles as lawyers and leaders.

1 Kuh, G. D., Kinzie, J., Buckley, J. A., Bridges, B. K., & Hayek, J. C. (2006). What matters to student success: A review of the literature (ASHE Higher Education Report). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

2 Strayhorn, T. L. (2018). College students’ sense of belonging: A key to educational success for all students. New York, NY: Routledge.

Annual Results 2020 Diversity & Exclusion: Institutional Support for Diversity

This year for the first time, LSSSE introduced a set of questions focused on diversity and inclusion that supplement related questions from the primary survey. The Diversity and Inclusiveness Module examines environments, processes, and activities that reflect the engagement and validation of cultural diversity and promote greater understanding of societal differences. The 2020 LSSSE Annual Results Diversity & Exclusion report presents data about how diversity in law school can prepare students for the effective practice of law upon graduation. In our next three posts, we will highlight key findings from the report and suggest some areas for improvement.

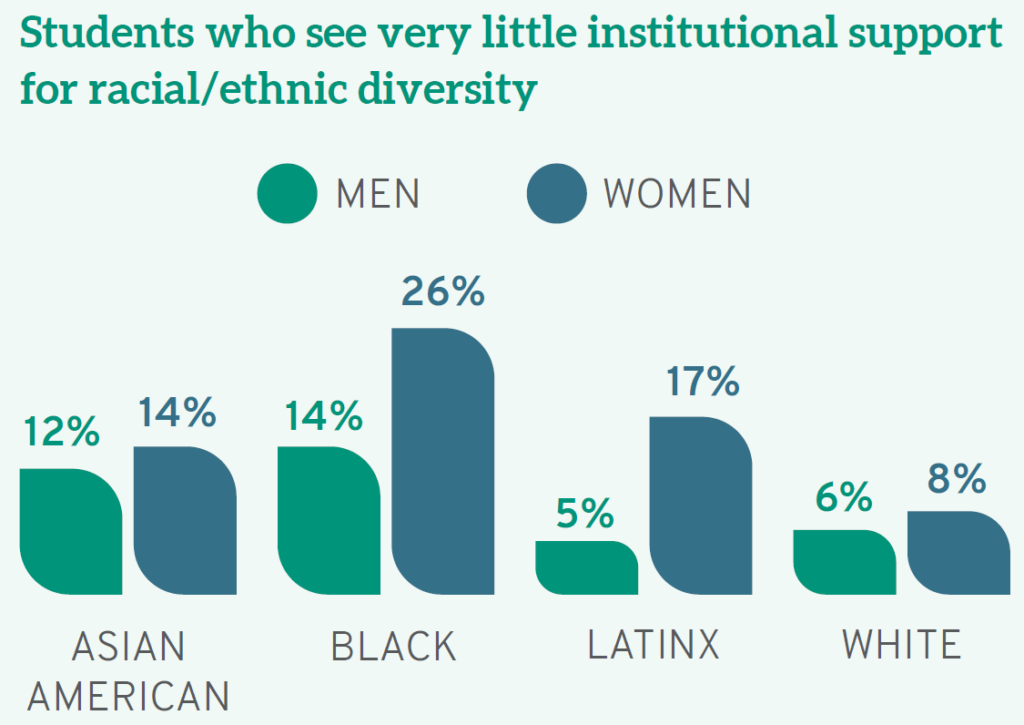

Support for diversity in law school must begin with the institution. Yet many students of color do not see their campus as supportive of racial/ethnic differences. Almost a quarter (23%) of Black law students nationwide say their schools do "very little" to create a supportive environment for race/ethnicity, compared to just 6.8% of White students. At the opposite end of the spectrum, 32% of White students believe their schools do "very much" to support racial/ethnic diversity, compared to only 18% of their Black classmates. Men (37%) are also more likely than women (26%) and those of another gender identity (7.5%) to believe their campus is very supportive of racial/ethnic diversity. Even more dramatic are intersectional identity findings, as a full 26% of Black women— more than any other raceXgender group—see their schools doing "very little" to create an environment that is supportive of different racial/ethnic identities, as compared to just 5.5% of White men (while 72% of White men believe their schools do "quite a bit" or "very much" in this arena).

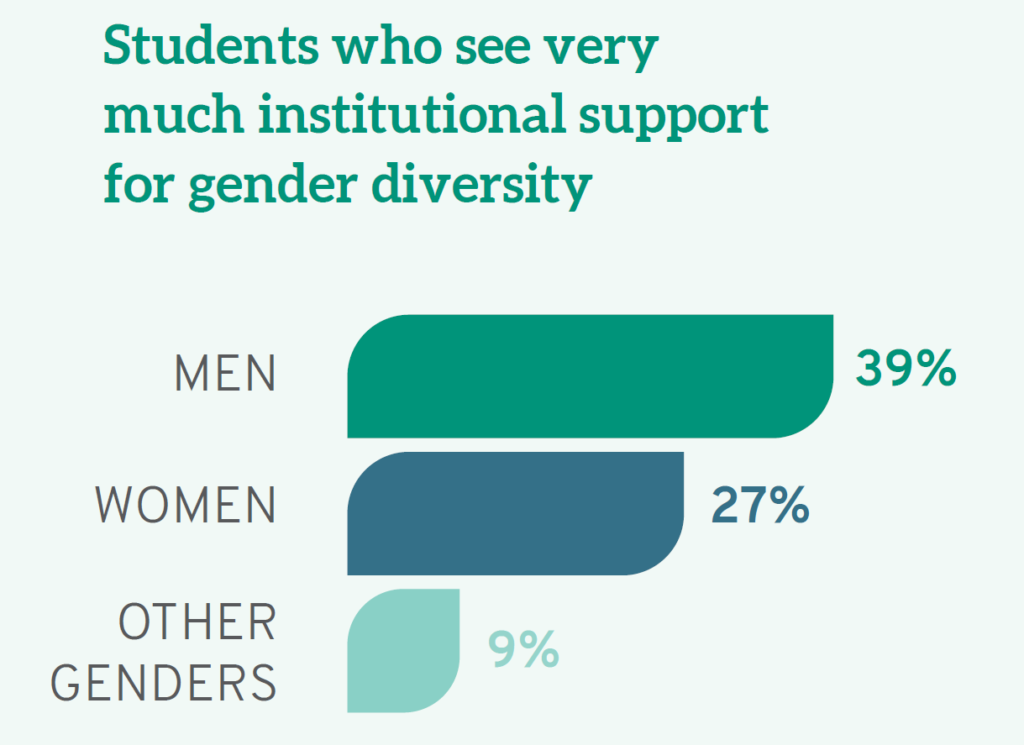

Men are also more likely to see their campus as a "supportive environment for gender diversity," with 39% believing this "very much" as opposed to 27% of women students, and only 9% of students who identify as another gender identity. Furthermore, White students as a whole (33%) see the campus as very supportive of people of different genders, compared to 21% of Native Americans and Black students. Again, the views of White male students differ significantly from most others with a full 40% seeing their campus as very supportive of gender difference. In short, women as well as others from less privileged groups do not see their schools as particularly supportive of gender inclusivity.

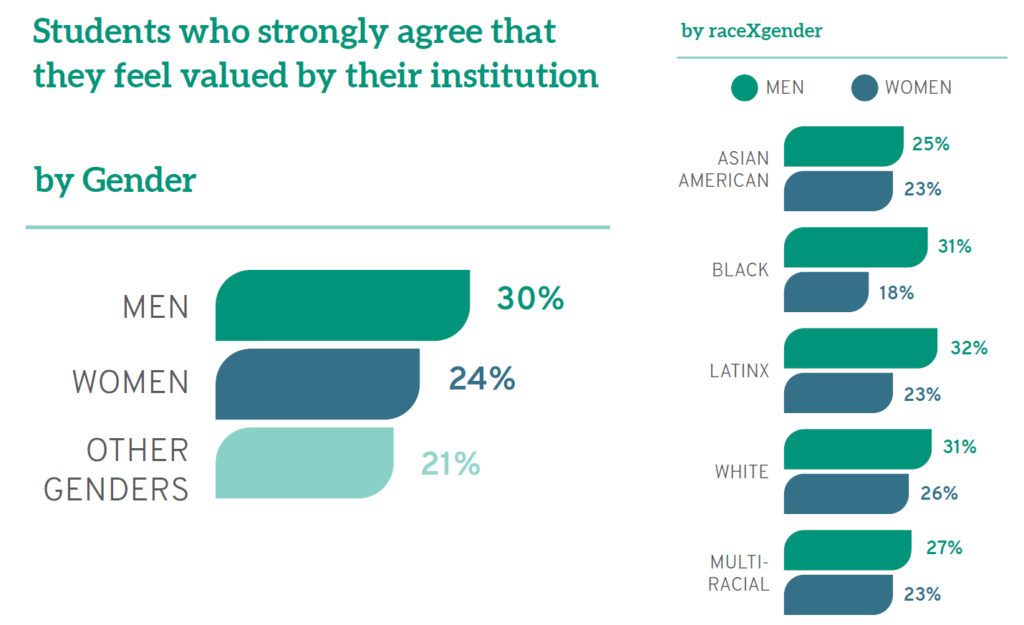

Not surprisingly, given the relative lack of support they see for racial/ethnic and gender diversity on campus, women and students of color also believe their schools are less invested in them as individuals. When asked whether they "feel valued" by their law school, a full 30% of men "strongly agree" compared to only 24% of women and 21% of those who identify as neither male or female. Similarly, the racial/ethnic group most likely to "strongly agree" is Whites (28%). In fact, while Latinos, White men, and Black men "strongly agree" that they are valued at roughly equal rates, men feeling more valued than women is consistent across every racial/ethnic group. Furthermore, students who are the first in their families to earn a college degree, often called "first-gen" students, feel less valued by their institution: a full third (33%) note they do not feel valued, compared to a quarter (25%) of others, which is also a significant proportion of law students overall.

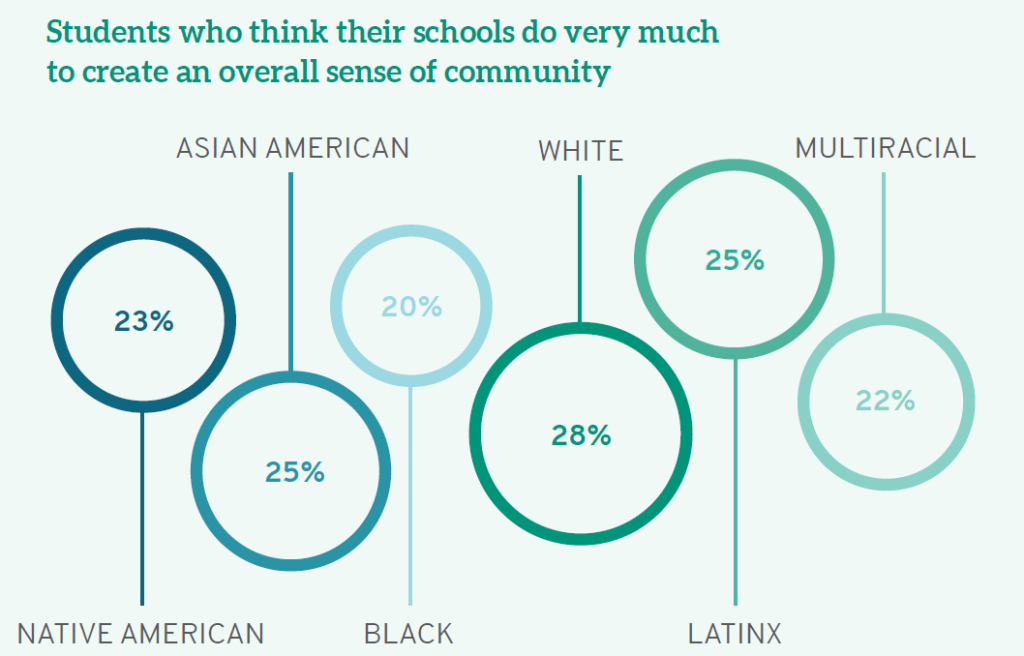

Institutions can put mechanisms in place to foster community among those on campus, regardless of their background or experiences. Finding this common ground helps all students understand that they belong and that others who may be different should be equally welcome. Again, White students are most likely to believe their institution emphasizes the importance of "creating an overall sense of community among students." While 28% of White students think their schools do this "very much," smaller percentages of students of color feel similarly. Even more disheartening, 18% of Black students and 14% of Latinx students think their schools do "very little" to foster community.

Many law schools have made concerted efforts to add student diversity to their campuses. But once students enroll, we owe it to them to provide a safe and welcoming environment, one where they feel valued, where they can be themselves, where they acquire the tools they need to succeed in the workplace, and where they can thrive. Admitting and even enrolling more students of color, first-gen students, students who identify as LGBTQ, and women is not enough unless that diversity is accompanied by inclusion. Law schools that want their students to succeed as future lawyers and leaders must commit to fostering a campus community where the most vulnerable and non-traditional are encouraged to reach their full potential, where faculty are expected to train students not only for the global marketplace but for the realities of American life, and where all students appreciate their own backgrounds, biases, and responsibilities to the profession.

LSSSE Annual Results 2019: The Cost of Women’s Success (Part 4)

The Troubling Secret to Success

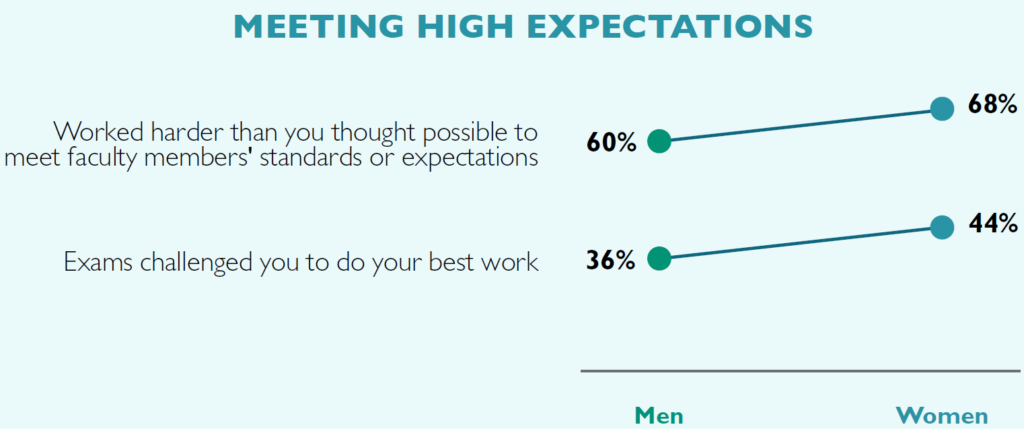

What is the secret to the success of female law students? They enter law school with fewer resources and amass significant burdens once enrolled, but perform at equal or higher levels than their male peers along many metrics. The data suggest one clear answer: women law students work extraordinarily hard, juggling their various personal and academic responsibilities at the expense of self-care. While most students work hard to meet the high expectations of their professors, women students report sustained effort at higher levels than their male peers. A full 68% of women note that they “Often” or “Very Often” worked harder than they thought they could to meet faculty members’ standards or expectations, compared to 60% of men. Similarly, higher percentages of female students than male rise to the challenge of submitting their best work on exams. LSSSE respondents were asked to report “the extent to which your examinations during the current school year have challenged you to do your best work” on a 7-point scale. Remarkably, 44% of women report the highest level of engagement (a 7 out of 7) as compared to 36% of men. Again, these findings of hardworking women are consistent across race/ethnicity.

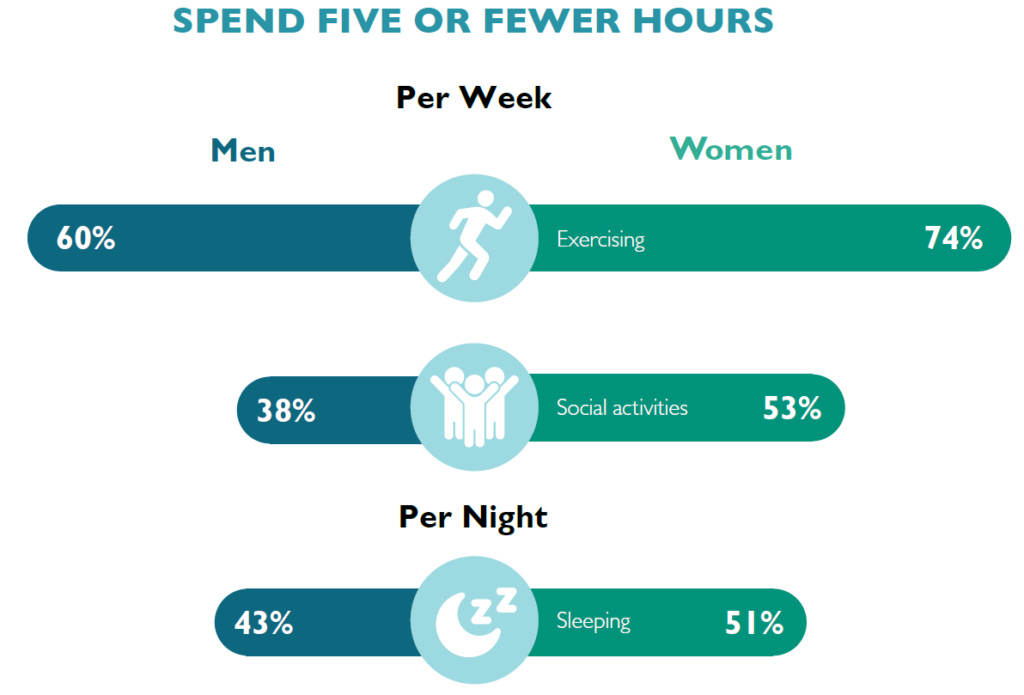

Tragically, the hard work that women dedicate to enabling their success comes at a significant cost. The tradeoff is that women are much less likely than men to engage in important social, leisure, and self-care activities. Each of these findings is consistent across racial/ethnic groups when comparing women with men. For instance, 41% of women spend zero hours per week reading for pleasure, compared to 25% of men. Similarly, the overwhelming majority of women law students find little time for physical fitness, with 74% reporting that they exercise no more than 5 hours a week (along with 60% of men). Expanding this concept to other leisure activities—including watching TV, relaxing, or even partying—does not improve this gender disparity. More than half (53%) of women law students spend five or fewer hours per week engaged in any of these social activities, compared to just over a third (38%) of men. Furthermore, half (51%) of women report sleeping five or fewer hours per night in an average week, along with 43% of men. In the scramble to get ahead academically, women are overlooking downtime; they are prioritizing their academic success at the expense of their own wellbeing. Such limited opportunities to disconnect from schoolwork, engage in physical fitness, rest, relax, and socialize with others can have serious implications for the long-term physical and mental health of women law students.

For more in-depth analysis about gender disparities in legal education, you can read the entire LSSSE 2019 Annual Results The Cost of Women’s Success (pdf) on our website or contact us.

LSSSE Annual Results 2019: The Cost of Women’s Success (Part 3)

Opportunities for Improvement

Given the many challenges facing women upon entry to law school, it is no surprise that there are also opportunities to improve the experience for women students in legal education. LSSSE data on concepts as varied as classroom participation, caretaking, and debt make clear that women need greater support.

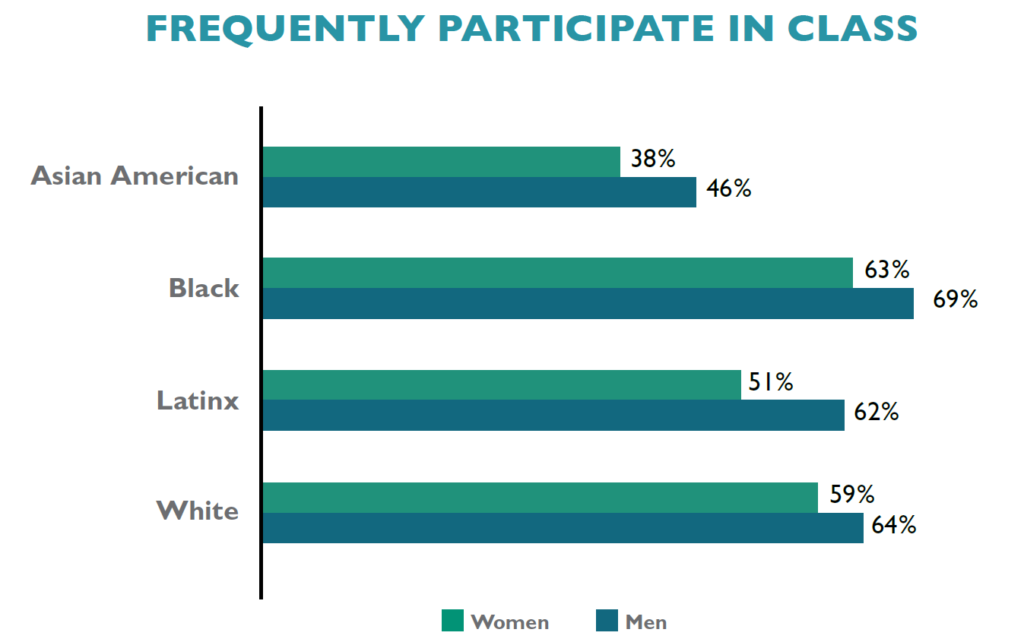

Engagement in campus life is an especially significant indicator of success. Law students who are deeply invested in both classroom and extracurricular activities tend to maximize opportunities for success overall. As stated in a previous post, women are just as likely as men to be involved in various co-curricular endeavors. Yet, smaller percentages of women than men are deeply engaged in the classroom. While 64% of men report that they “Often” or “Very Often” ask questions in class or contribute to class discussions, only 58% of women do. This gender disparity remains pronounced within every racial/ethnic group, as men participate in class at higher rates than women from their same background. There are also interesting variations by raceXgender, with Black men frequently participating at higher rates than any other group (69%), and at almost twice the rate of Asian American women (38%).

Many women students also spend numerous hours during their law school careers providing care to household members. For instance, 11% of women report that they spend more than 20 hours per week providing care for dependents living with them, as do 8.6% of men. These competing responsibilities require a significant investment of time, which could otherwise be spent on studying for class, working with faculty on a project outside of class, or even engaging in leisure activities. Instead, these students are taking care of their families.

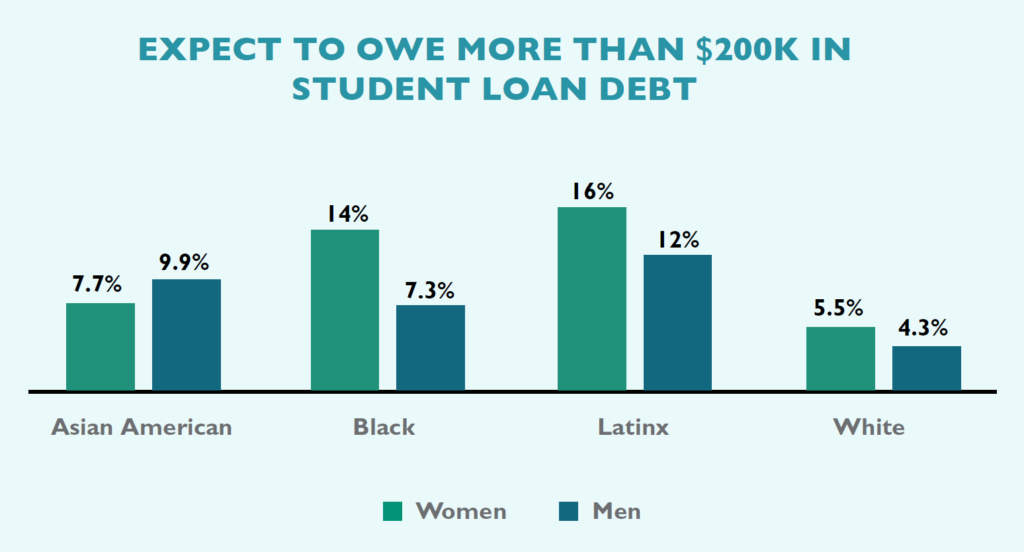

An especially troubling discovery is that high percentages of women than men incur significant levels of debt in law school. Among those who expect to graduate from law school with over $160,000 in debt are 19% of women and 14% of men. This gender difference remains constant within every racial/ethnic group. Even more alarming is the disparity among those carrying the highest debt loads: 7.9% of women will graduate from law school owing over $200,000 as compared to 5.5% of men. LSSSE data not only confirm existing research on racial disparities in educational debt, with people of color and especially Black and Latinx students borrowing more than their peers to pay for law school, but also reveal that women carry a disproportionate share of the debt load as compared to men. Furthermore, when considering the intersection of race/ethnicity and gender, we see that women of color specifically are graduating with extreme debt burdens.

Next week, we will conclude this series with some troubling trade-offs that women make to overcome the disadvantaged position in which they often find themselves relative to their male counterparts. You can read the entire LSSSE 2019 Annual Results The Cost of Women’s Success (pdf) on our website.