A Long-Term Look at Relationships with Law School Peers, 2004-2023

A common misconception about law students is that their competition with each other for grades, jobs, and prestige creates a stressful and hostile law school environment. However, this is not the case for most law students who often find opportunities for support and friendship among their peers. Law students share common challenges and goals, and they can benefit from exchanging ideas and resources with each other. Many law schools also foster a culture of collegiality and mutual respect, where students are encouraged to help each other and celebrate each other's achievements. Rather than being a source of stress, peer relationships can be a source of resilience and well-being for law students. In fact, LSSSE data from 2023 show that only 38% of law students experienced quite a bit or very much stress or anxiety because of competition with peers. They are far more likely to be substantially stressed by academic performance (80% of students) and academic workload (79% of students).

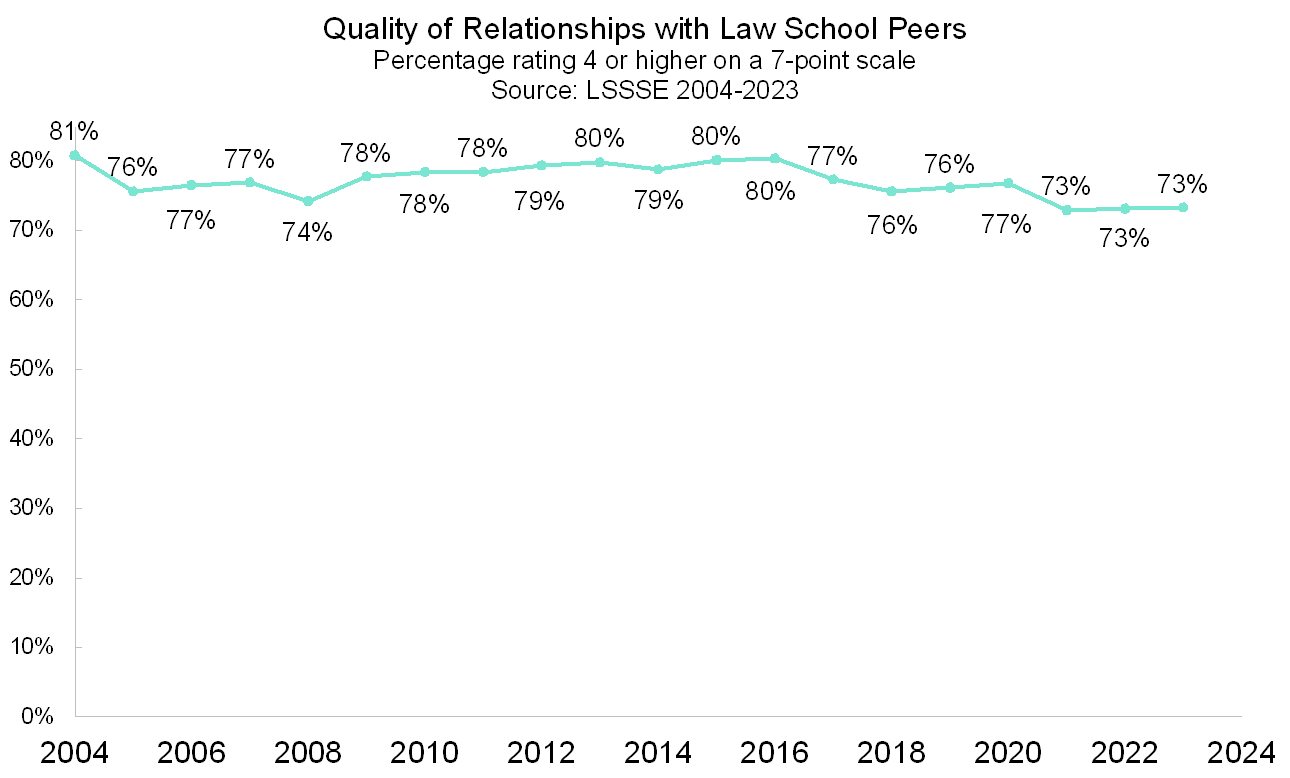

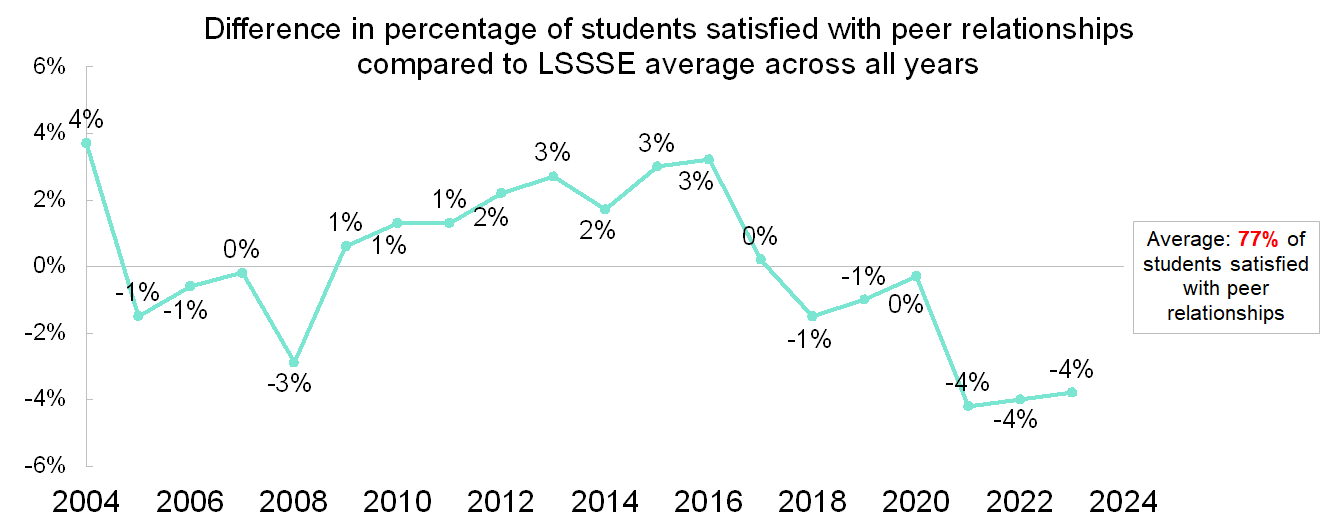

Since the 2004 LSSSE inaugural survey, an average of 77% of law students have said that their overall relationships with other students are mostly positive (at least a 4 on a 7-point scale). This number has fluctuated over time, with 81% of students having mostly positive relationships in 2004 and 73% of students feeling similarly in 2023.

If we compare the percentage of students having an overall positive relationship with peers to the all-time LSSSE national average of 77%, we can see that the last several years have had slightly lower levels of peer satisfaction.

Although satisfaction with peer relationships was already on a somewhat downward trajectory before COVID-19, the notable decrease in relationship satisfaction during the 2020-2021 academic year may be largely driven by the decrease in relationship satisfaction among 1L students. In the spring of 2020 (largely before COVID-19 shutdowns started), 80% of 1L students were satisfied with their relationships with their fellow students. In the spring of 2021 after a year of huge disruptions in the law school environment including widespread online learning, only 72% of 1L students felt this way. However, 74% of 3L students were satisfied with their peer relationships in 2020 and again 74% of 3L students felt this way in 2021. Students who were introduced to law school in a time of necessary isolation were understandably somewhat less able to bond with their classmates. Orientation programs, study groups, moot courts, clinics, extracurriculars, and informal gatherings were either canceled, restricted, or moved online. These disruptions may have hindered the ability of 1L students to establish friendships and build rapport. Furthermore, online learning may have decreased the frequency and quality of interactions among students, as well as the sense of belonging and community that stems from being physically present in a shared space. Nevertheless, relationships among law students remained positive overall, showing that even the limitations of pandemic life did not prevent characteristically creative and resilient law students from forging relationships with each other. It will be interesting to examine how law students feel about their relationships with each other in future years now that life has largely returned to the pre-pandemic normal.

Online Learning and Law Student Age

The 2020-2021 academic year was unlike any other, forcing students and instructors to adapt to a different way of living and learning. Prior to the pandemic, law schools were less likely than other sectors of academia to embrace online learning. But when it became clear that COVID was not going away, many law schools shifted to primarily online interactions. The Online Learning module, which debuted with the spring 2021 LSSSE survey administration, was developed to capture students’ perceptions and experiences with online classes during this peculiar academic year and potentially beyond. Although the abruptness of the transition to online learning and the external stressors inherent to pandemic life may make these data unique in some ways, in other ways they are an excellent starting point for law schools to learn about how to structure their curriculum to leverage the strengths of the online environment, even as traditional in-person learning resumes.

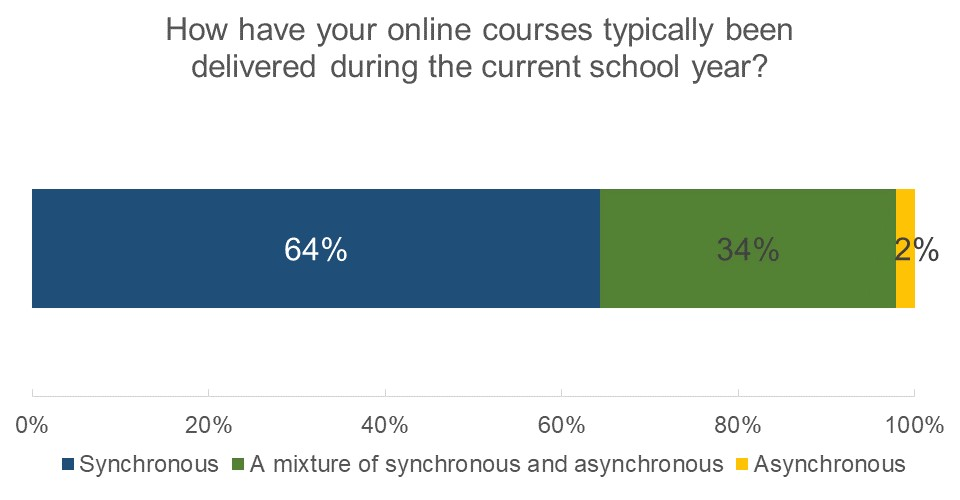

What types of online learning experiences were law students having in 2020-2021? Nearly all students who took online courses had at least some synchronous element in their courses. Nearly two-thirds of students typically had synchronous courses while another third experienced a mixture of synchronous and asynchronous content. Only about two percent of students typically received only asynchronous content.

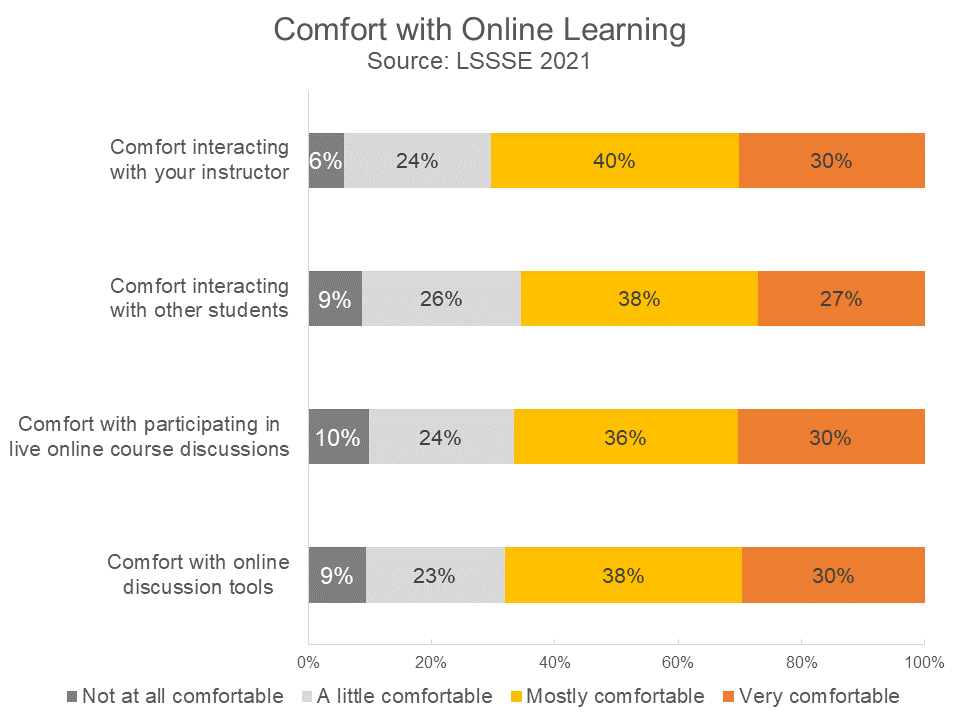

Most law students were fairly comfortable with online learning. Seventy percent of students were mostly comfortable or very comfortable interacting with the instructor of their online courses, and around 65% felt similarly about interacting with the other students. About two-thirds of students were comfortable with online discussion tools such as discussion boards and forums and about two-thirds of students were comfortable with live online course discussions.

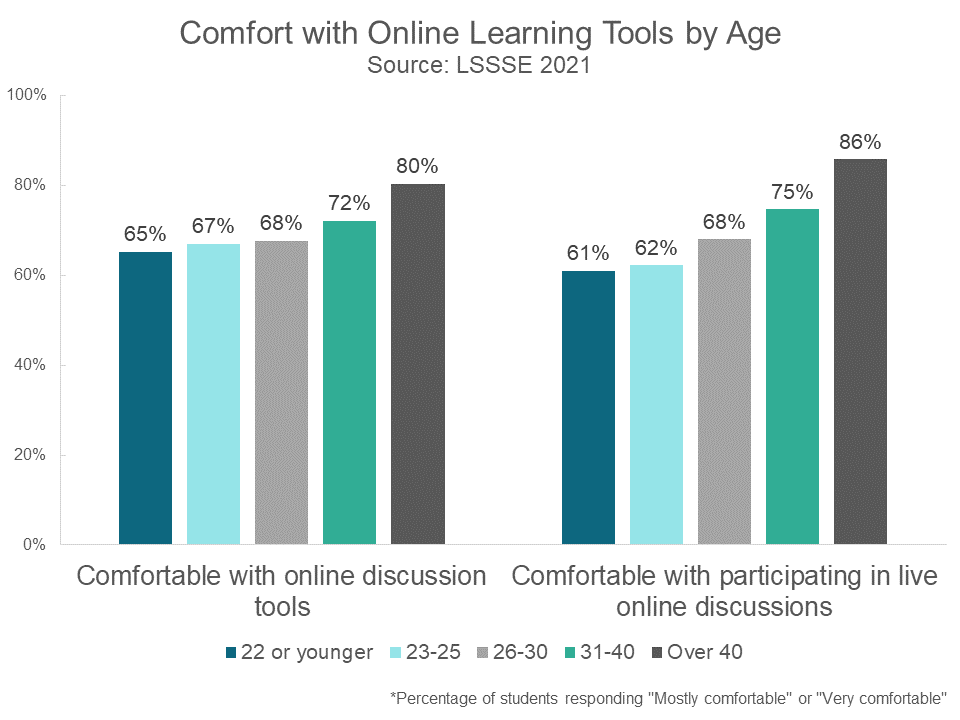

Interestingly, older students were more likely to be comfortable with virtually all aspects of online learning relative to their younger peers. In fact, comfort with online learning tools increased steadily across age brackets. The vast majority (86%) of students over 40 were comfortable participating in live online discussions compared to only around 62% of students 25 or younger.

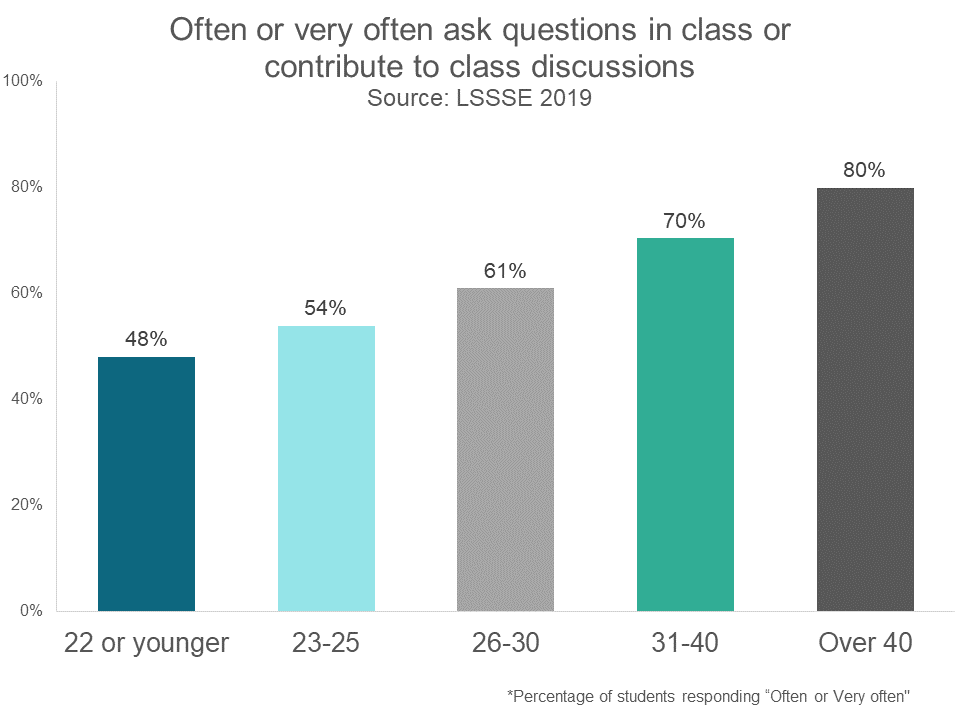

This age discrepancy in participation exists in physical classrooms too. In 2019, before the widespread adoption of online law classes, 80% of students over age 40 often or very often asked questions in class or contributed to class discussions, compared to 48% of those 22 or younger and 54% of those between 23 and 25. In fact, students under age 30 may be somewhat more comfortable with online course discussions than in-person ones, even though their overall participation is less than that of their older classmates regardless of the class setting.

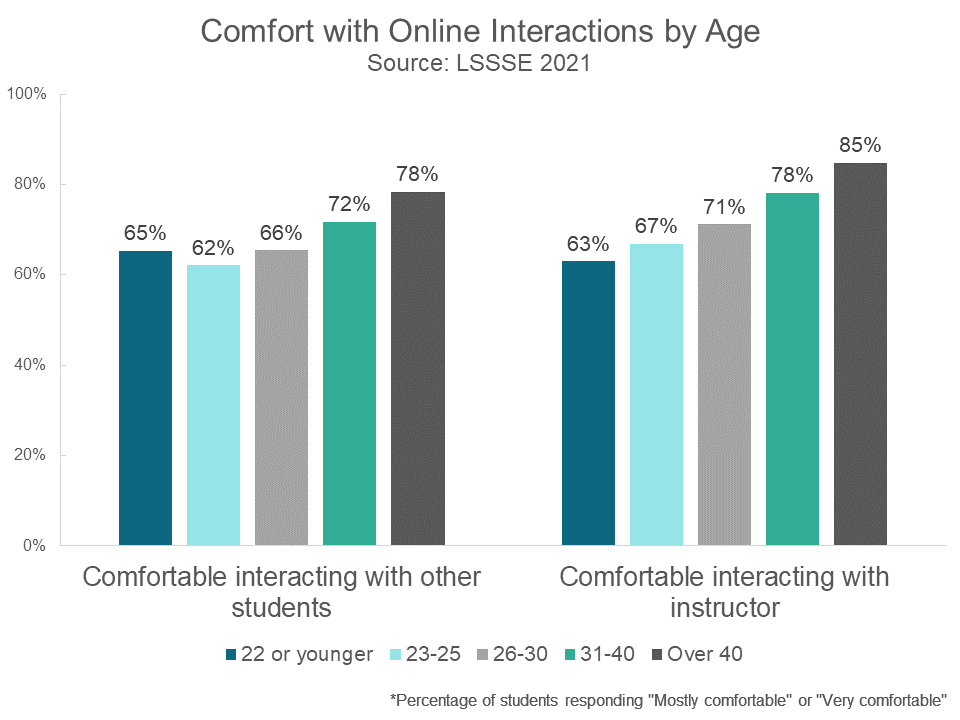

Older students were also more likely to be comfortable interacting with their peers and instructors online. Only 63% of students age 22 or younger were comfortable interacting with their instructors online, compared to a full 85% of students over 40. Among students between the ages of 23 and 25 (the most common age for a law student), less than two-thirds were comfortable interacting with other students in their online classes, compared to a full 78% of students over 40.

Although popular media tends to suggest that younger people are more adept with technology, the oldest Millennials – the first generation to live much of their lives online – are now in their forties. Perhaps these older students have adapted to so much online technology across their personal and professional lives that another pivot was not as disruptive as it was for their younger colleagues. Regardless of the reason, the LSSSE data show clearly that law schools should make a deliberate effort to support the technological skills and online engagement levels of their youngest students.

Guest Post: The Imperative of Inclusive Socratic Classrooms

The Imperative of Inclusive Socratic Classrooms

The Imperative of Inclusive Socratic Classrooms

Jamie R. Abrams, J.D., LL.M

Professor of Law, University of Louisville Brandeis School of Law

Legal education is navigating multiple reform initiatives that call for scalable and versatile approaches. Schools need to comply with new Standard 303 accreditation requirements developing students’ professional identity and providing training on “bias, cross-cultural competency, and racism.” Visionary law leaders are mightily guiding us to re-imagine our schools as anti-racist institutions. Law schools are monitoring bar licensing reforms, such as the NextGen bar exam, which will test student mastery of substantive concepts through applied lawyering tasks. Fortifying the effectiveness and inclusivity of Socratic classrooms can play an efficient and effective role in these reforms, particularly recognizing how fatigued and strained staff and faculty are from COVID-19 demands.[i]

Critical theorists have argued for over half a century that the Socratic method can foster classrooms that are competitive, hierarchical, adversarial, marginalizing, privileging, and constraining, particularly for women and students of color.[ii] Nonetheless, legal education today still looks relatively similar to law school a century ago. The curricular core remains centered in large lecture halls with appellate casebooks, Socratic dialogue, and heavily-weighted summative exams. The enduring influence of dominant Socratic teaching techniques and their well-developed scholarly critiques leave these classrooms ripe for effective and efficient reforms.

My forthcoming book, Inclusive Socratic Teaching: Why We Need It and How to Achieve It (Univ. of Calif. Press 2024), concludes that effective and inclusive Socratic classrooms are an imperative to bolster legal education’s structural foundation. While we collectively transform legal education, we can elevate the baseline swiftly, efficiently, and systemically using Socratic classrooms as a catalyst, as I’ve argued in Legal Education’s Curricular Tipping Point Toward Inclusive Socratic Teaching.

Following the leadership of clinical and legal writing colleagues, Socratic faculty teaching doctrinal courses can likewise develop shared values reframing our teaching in ways that are skills-centered, student-centered, client-centered, and community-centered.[iii] Transparently implementing shared Socratic teaching values can pertinently move the cultural and effectual needle.

Student-centered Socratic teaching is a vital component to inclusive and effective Socratic classrooms. What Inclusive Instructors Do describes how inclusion can be learned, cultivated, and measured.[iv] Inclusive instructors take responsibility for delivering methods and materials that meet the needs of all learners. They learn about their students and care for them. They continuously adapt to help students thrive and belong.[v]

The speed of a girl around town is about four kilometers per hour, or two and a half if she is wearing heels over six centimeters find a sex date in your area uk. The zone of possible contact is five meters, no more. So you're getting... How much are you getting? (Damn it, they told me to do my math properly, you'll need it!) Well, like, five seconds.

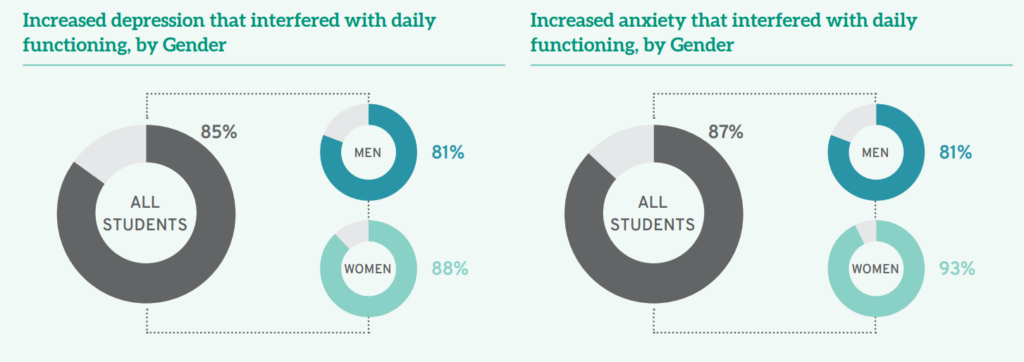

The annual Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) is an important portal into examining the needs, challenges, and lived experiences of our students collectively, particularly as it reveals a changing climate. LSSSE’s 2021 Annual Report yields a critical call to action to support our students. It reveals how students are navigating heightened levels of “loneliness, depression, and anxiety.”[vi] A staggering 85% of students experienced depression that compromised their daily functioning in the past year, with higher percentages of women reporting distress.[vii]

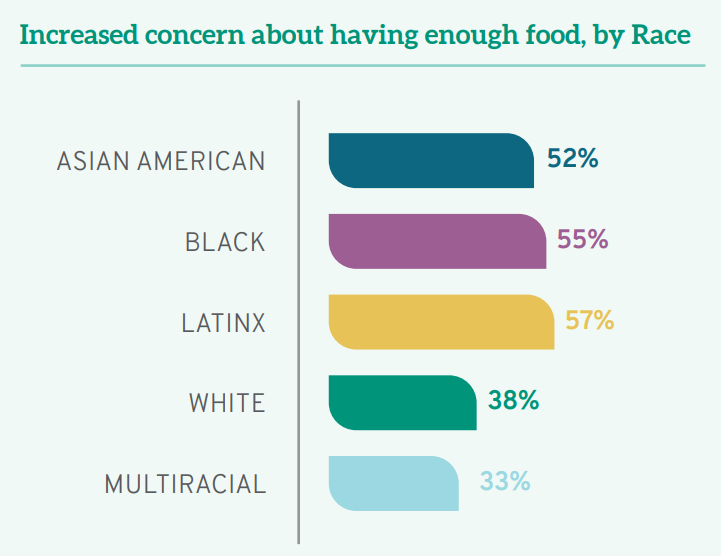

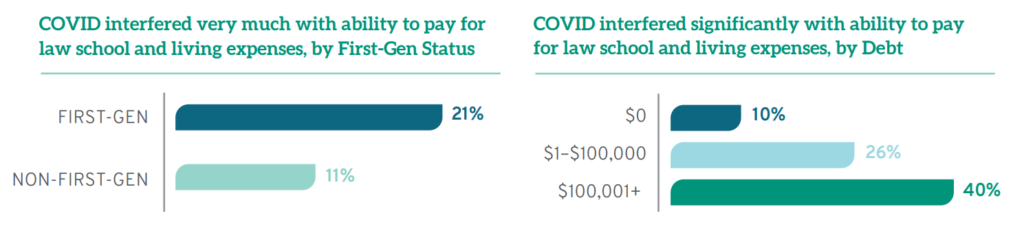

Amid COVID-19, our students have navigated our courses worried about food security, particularly Latinx, Black, and Asian American students.[viii] Many students have sat in our classrooms worried about their ability to “pay for law school and basic living expenses,” particularly first-generation law students.[ix]

Paolo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed reminds us that “trusting the people is the indispensable precondition for revolutionary change.”[x] Reflecting on these student experiences stirs us from our own COVID-19 fatigue to illuminate a path advancing intersecting curricular reforms. While no professor can alleviate the essential external challenges of our students, we can fortify the dominant Socratic classroom experience to minimize its abstract perspectivelessness. Socratic classrooms can be student-centered, skills-centered, client-centered, and community-centered, pivoting from professor-centered, power-centered, and anxiety-inducing. LSSSE’s analysis, reinforced by our direct student engagement, inspires us to reform Socratic classrooms with students, not simply for students. Sensitized to our student experiences liberates us to disrupt the status quo knowing that all students might benefit from greater connection, intentionality, and applicability in our Socratic classrooms.

Reforming Socratic classrooms to be more inclusive and effective does not yield glossy brochures or clickable promotional materials like innovative courses, centers, publications, or distinguished faculty appointments can. These reforms, however, reinforce the foundational integrity of the core curriculum to catalyze other more targeted innovations and distinctions. Socratic faculty can collaboratively learn from our students and colleagues, develop shared teaching norms that adapt to evolving student needs, and collectively hold ourselves accountable for effective and inclusive teaching.

[i] Meera E. Deo, Investigating Pandemic Effects on Legal Academia, 89 Fordham L. Rev. 2467 (2021); Meera E. Deo, Pandemic Pressures on Faculty, 170 Pa. L. Rev. Online – (2022), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4029052.

[ii] See e.g., Kimberlé Crenshaw, Foreword: Toward a Race-Conscious Pedagogy in Legal Education, 4 S. Cal. Rev. L. & Women’s Stud. 33, 34 (1994); Jamie R. Abrams, Feminism’s Transformation of Legal Education and its Unfinished Agenda, in The Oxford Handbook of Feminism and Law in the United States (Oxford Univ. Press, Eds. Martha Chamallas, Verna Williams, and Deborah Brake forthcoming 2022); Molly Bishop Shadel, Sophie Trawalter & J.H. Verkerke, Gender Differences in Law School Classroom Participation: The Key Role of Social Context, 108 Va. L. Rev. Online 30 (2022).

[iii] See Jamie R. Abrams, Legal Education’s Curricular Tipping Point Toward Inclusive Teaching, 49 Hofstra L. Rev. 897 (2021); Jamie R. Abrams, Reframing the Socratic Method, 64 J. Legal Educ. 562 (2015).

[iv] Tracie Marcella Addy, Derek Dube, Khadijah A. Mitchell & Mallory E. SoRell, What Inclusive Instructors Do 4 (2021).

[v] Id. at x (foreword).

[vi] Meera E. Deo, Jacquelyn Petzold, and Chad Christensen, The COVID Crisis in Legal Education, Law School Survey of Student Engagement Annual Report 5 (2021).

[vii] Id. at 12.

[viii] Id. at 5.

[ix] Id.

[x] Paolo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed 34 (1973).

Part 1: The COVID Crisis in Legal Education: Impact on Core Mission and Enriching Experiences

Because LSSSE has been annually administered since 2004, the survey was well-positioned to capture shifts in students’ perceptions and behaviors during the uniquely challenging 2020-2021 academic year. Our 2021 Annual Results, The COVID Crisis in Legal Education (pdf) draws from the core survey and two new modules (“Coping with COVID” and “Experiences with Online Learning”) to identify key struggles and successes of legal education during a period marked by uncertainty and disruption.

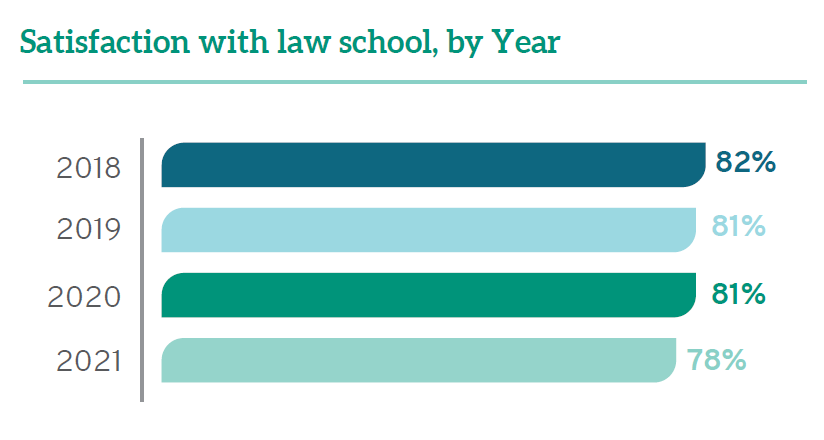

In the midst of a challenging year, some positives emerge from the data. Overall satisfaction remained high throughout legal education and comparable to past years. A full 78% of students in 2021 rated their entire educational experience in law school as “good” or “excellent,” which is similar to rates from recent years (82% in 2018, and 81% in 2019 and 2020). This is a testament to the significant efforts of faculty, staff, and administrators who pivoted to meet student needs as well as to the resiliency of the students themselves.

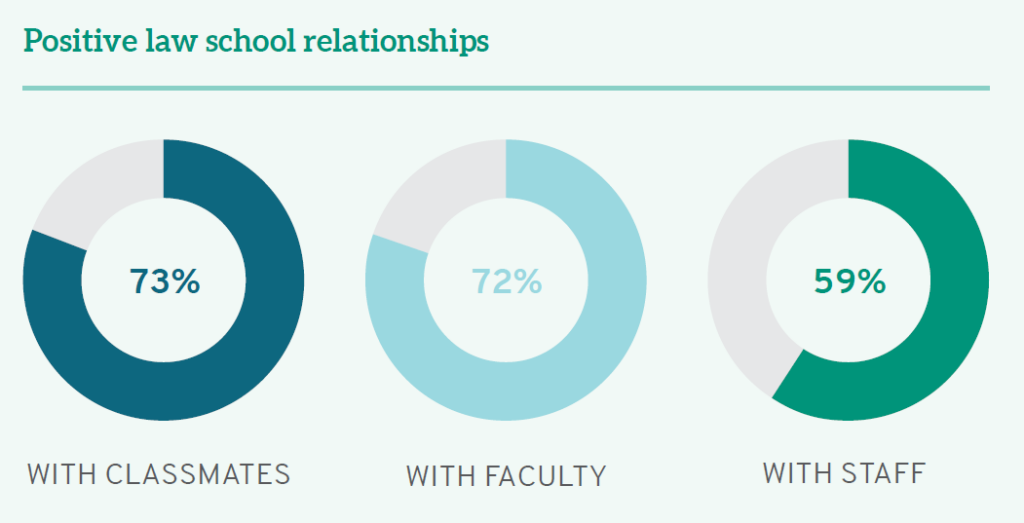

Nevertheless, the ability to forge and foster relationships has been especially difficult during the pandemic, which is borne out in the data. The percentage of students reporting positive relationships with staff dropped from 68% in 2018 to 59% in 2021—the lowest percentage recorded since LSSSE began collecting data on student-staff interactions in 2004. During those same years, positive student relationships with faculty and fellow students dropped just slightly from 76% to 72% and 76% to 73%, respectively. A full 93% of students appreciated that their law professors showed “care and concern for students” as the pandemic raged around them. First-year students were less likely to report positive relationships than 2Ls and 3Ls—likely because upper-class students could build on foundations they had cemented pre-COVID while 1Ls were attempting to start relationships from scratch in the midst of the pandemic.

The core of legal education remains relatively unchanged. Every year from 2018 to 2021, 85% of students have acknowledged that their schools contributed “quite a bit” or “very much” to their ability to acquire a broad legal education. There were also minimal changes this year compared to years past with regard to students developing legal research skills (80- 83%) and learning effectively on their own (81-82%).

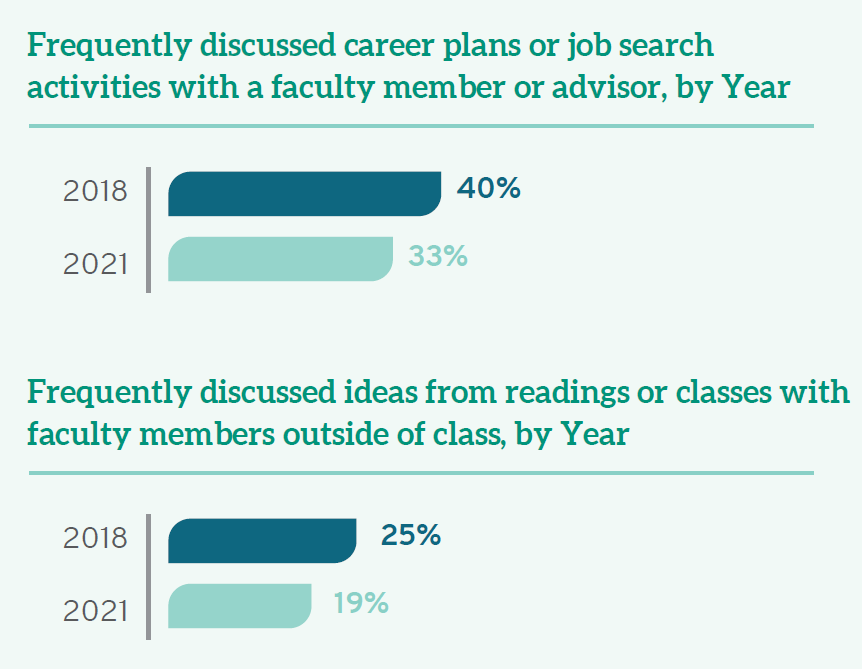

Yet the intangibles of legal education were significantly affected by COVID-19, with potential negative consequences on the professional competency of these future lawyers. A full 90% of students noted that COVID interfered with their ability to participate in special learning opportunities, including study abroad, internships, and other field placements. While discussions about course assignments and faculty feedback on academic performance remained constant, just one-third (33%) of all law students found frequent occasions to talk with faculty members or other advisors about career plans or the job search process (down from 40% in 2018), and only 19% frequently discussed ideas from readings or classes with faculty members outside of class (down from 25% in 2018). There were also fewer opportunities for students to work with faculty members on activities other than coursework.

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted nearly all aspects of life, and law school is no exception. Although law schools did their best to continue on with the education of the next generation of lawyers, there were still marked decreases in student engagement, particularly in building relationships and gaining experience outside the classroom. In our next post, we will explore the areas in which law students struggled the most in their lives and show how the pandemic disproportionately impacted those students who were already the most vulnerable.