Classroom participation by gender identity: 2023 update

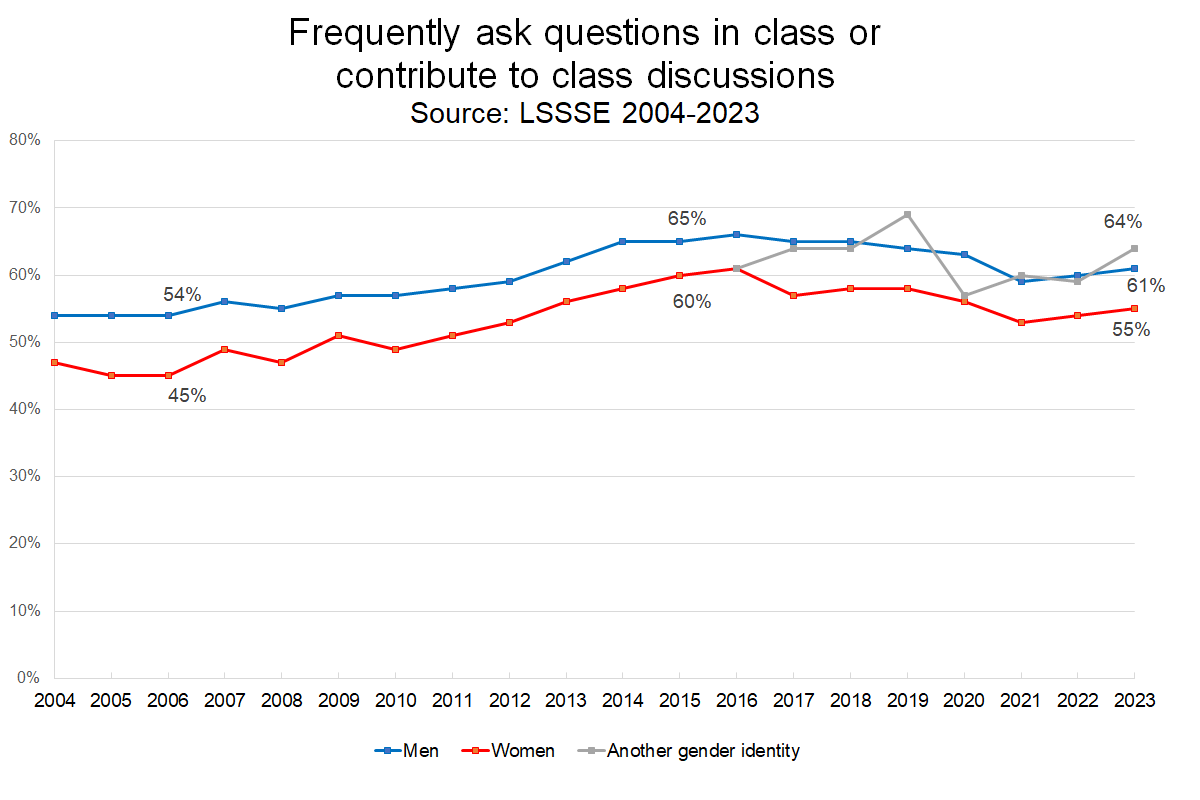

In a 2018 blog post, we showed a long-standing pattern of class participation by gender among law students in which men engage more frequently in class discussions than women. Although the percentage of students who frequently ask questions in class or contribute to class discussions has fluctuated over time, the gap between men and women has stayed remarkably consistent since the inaugural LSSSE survey in 2004. How does this pattern look five years later?

Through a pandemic, a switch to online learning, and a switch back to in-person learning, the pattern has continued to be remarkably consistent. In 2023, 61% of male law students “often” or “very often” participated in class compared to only 55% of female students. Students of another gender identity also generally participate in class more often than women, with nearly two-thirds (64%) of them frequently asking questions or contributing to class discussions in 2023.

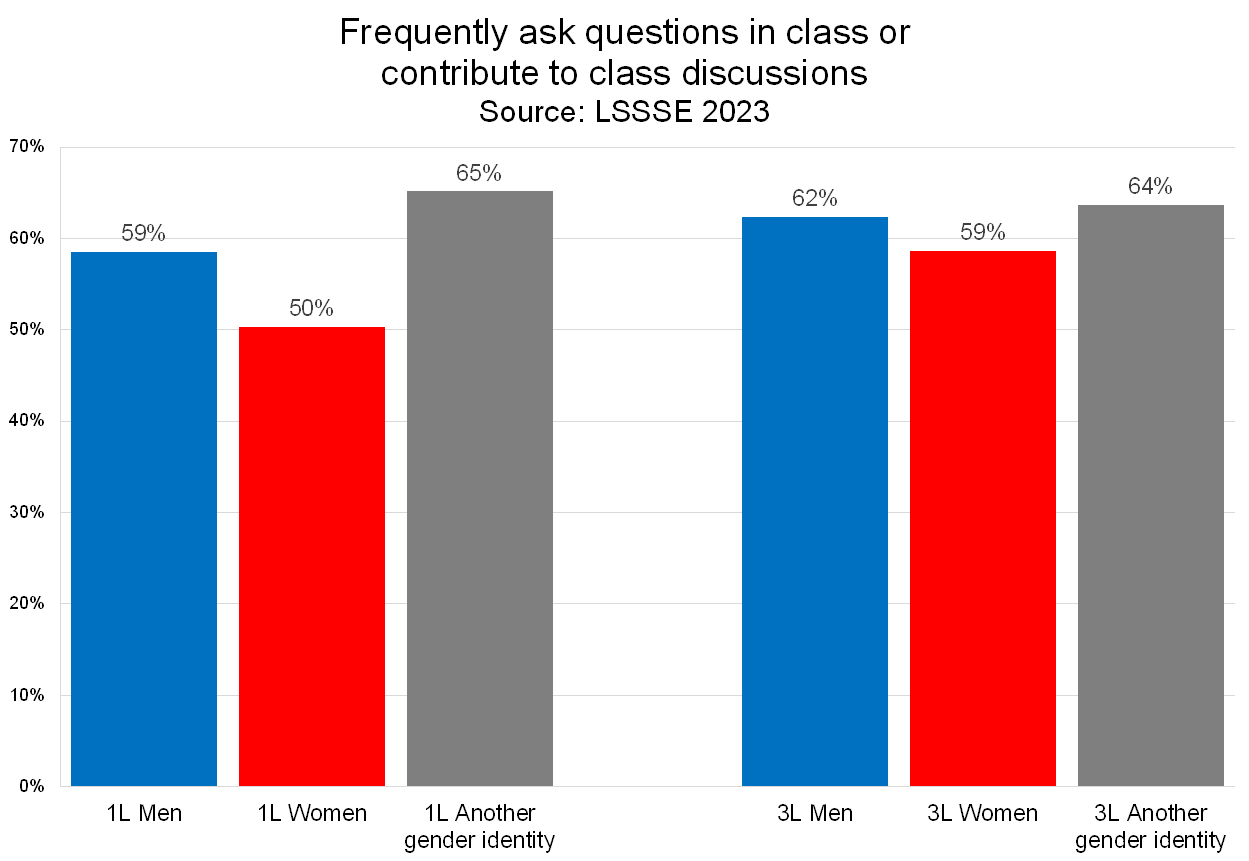

However, it appears that there are differences among classes in terms of participation by gender. 1L women are much less likely than 1L students of other genders to frequently ask questions or contribute to discussions, but 3L women are only somewhat less likely to do so relative to 3L students of other genders. Perhaps women gain confidence across their years as a law student or perhaps they become major contributors to class discourse only once they can be reasonably sure that their voices will be heard and respected.

Nonetheless, men and people of other gender identities are still slightly more likely to frequently ask questions or contribute to discussions even in that final year of law school. Finding ways to encourage women to participate in class conversations earlier will allow them to engage more meaningfully with their entire legal education in addition to elevating the discourse of the law classroom for all students.

Law School Support for Non-Academic Responsibilities

Law students vary in their amount and type of non-academic responsibilities, and they also vary in the degree to which they feel that their law school helps them cope with these responsibilities. In addition to their studies, some law students work, care for children or other dependents, and engage in community activities. We wanted to examine the degree to which students feel supported in these endeavors by their law schools.

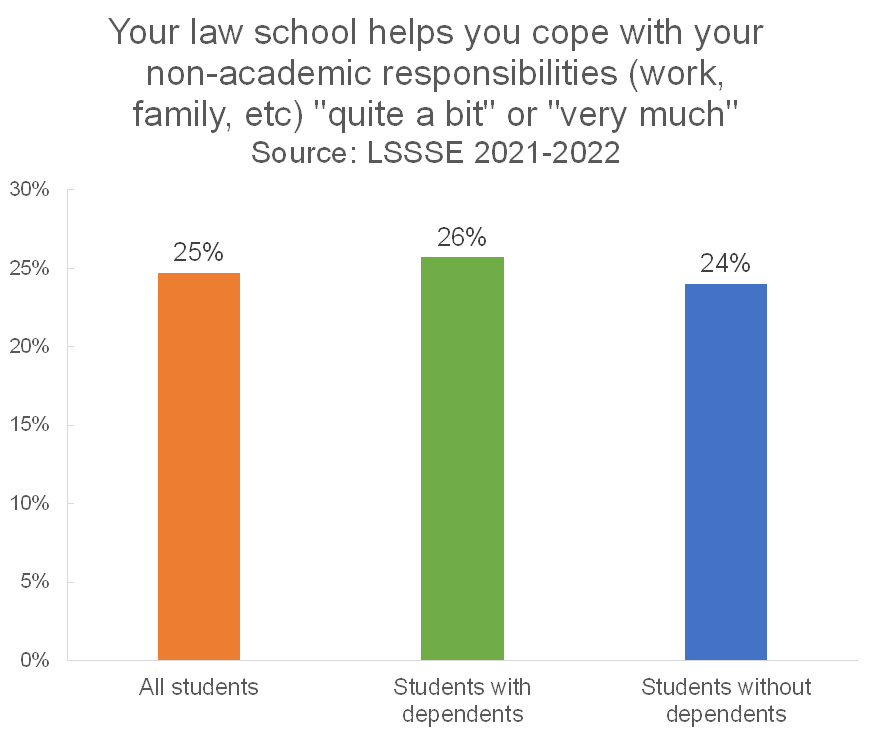

Time Spent Caring for Dependents

Thirty-eight percent of law students spend at least one hour per week caring for dependents living with them (parents, children, spouse, etc.). Interestingly, there is little difference in the percentage of students with and without dependent care duties who feel that their law school emphasizes helping them cope with their non-academic responsibilities. About a quarter of each group (26% of students with dependents and 24% of students without dependents) feel well-supported. However, students with dependents are slightly more likely to say that their law school does very little to help them cope with non-academic responsibilities. Two out of five (42%) of students with dependents feel this way compared to 38% of students without dependents.

Gender and Dependent Care

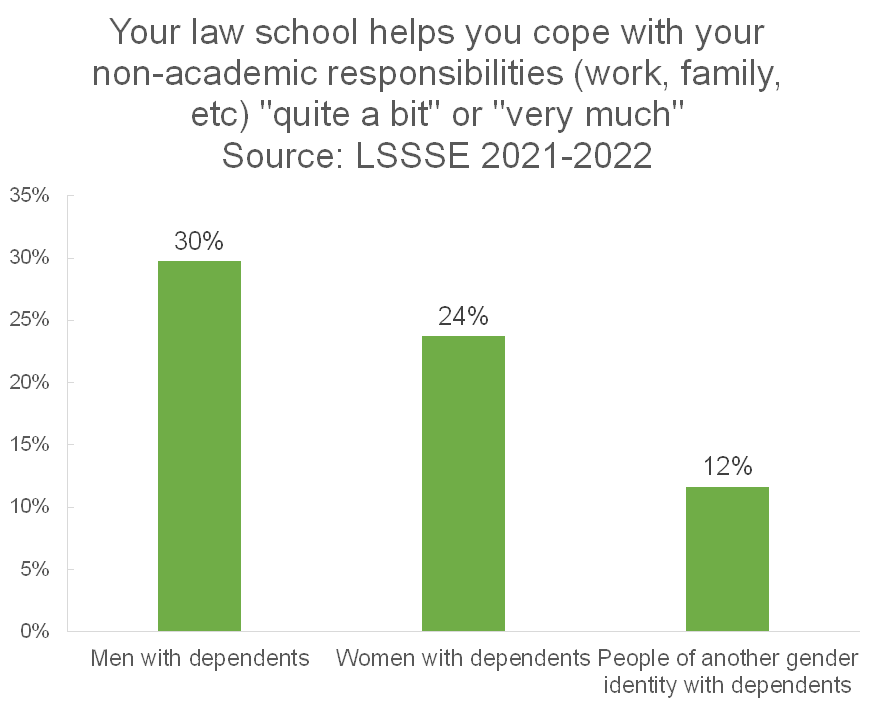

However, there are huge differences by gender. Men with dependent care responsibilities are much more likely to feel supported by their law schools than women with dependent care responsibilities, and both groups feel more supported than people of other gender identities with dependent care responsibilities.

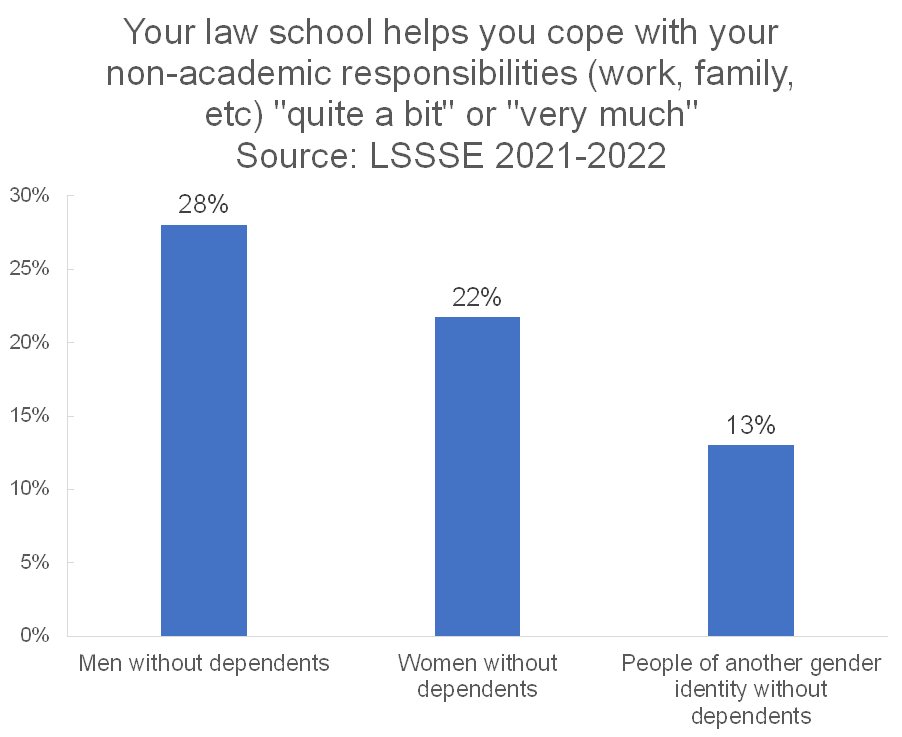

It appears, however, that this effect is more about gender and less about the dependent care responsibilities as we see this same disparity across gender among people without dependent care responsibilities.

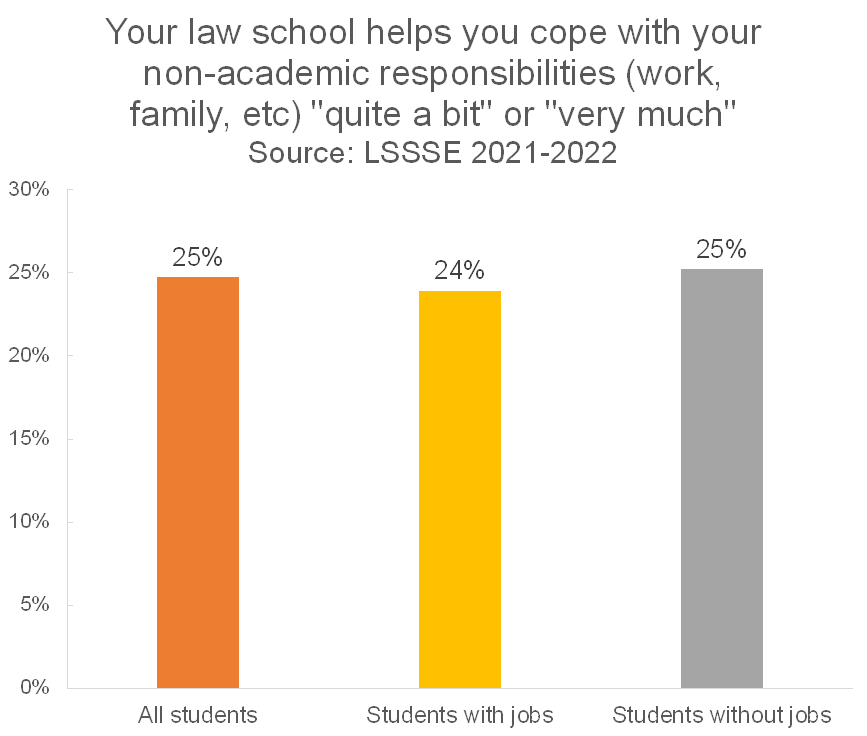

Time Spent Working for Pay

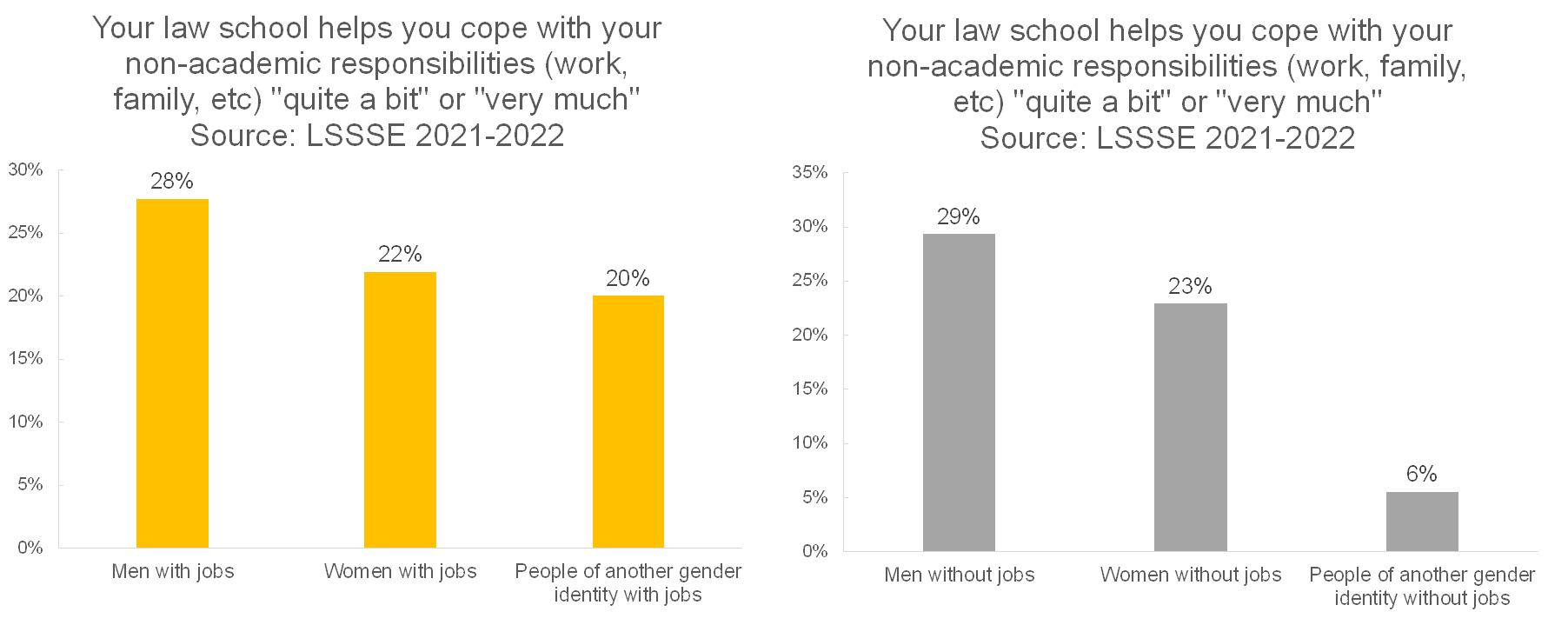

Similar to the pattern we see with dependent care duties, there is minimal difference in the perceived level of support for non-academic responsibilities between students who have jobs and students who do not. Around one in four students in either category say that their law school emphasizes supporting their non-academic responsibilities.

Gender and Employment

The gender pattern for perceived support is much the same for working/non-working students as it is for dependent care duties. Men are more likely to feel high levels of support than other students. However, people who identify as neither men nor women are actually more likely to feel highly supported in their non-academic responsibilities when they are employed (20% of students) relative to when they are not (6% of students).

Regardless of how they spend their time outside of law school, men are much more likely to feel highly supported in their non-academic responsibilities, people of another gender identity are very unlikely to feel supported, and women generally fall somewhere in between. Adequate support for non-academic responsibilities clearly looks different for different people, and it appears that gender is a major factor. Rather than focusing on student populations based on which responsibilities they have and how they spend their time outside of the classroom, law schools may want to consider the unique needs of women and people of other gender identities to close the gap in the degree of support they feel about coping with their non-academic responsibilities.

Better than BIPOC

Meera E Deo, JD, PhD

Meera E Deo, JD, PhD

The Honorable Vaino Spencer Professor of Law, Southwestern Law School

Director, Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE)

We should be precise with our language, especially when talking about race. In “Better than BIPOC,” I argue that BIPOC is a flawed term for empirical scholars to use, one that prioritizes historical oppression over ongoing realities and relies on virtue signaling rather than working toward meaningful change. In my previous essay “Why BIPOC Fails,” I explain how BIPOC can be misleading, confusing, and contribute to the invisibility of the very groups that should be centered in particular contexts. Thus, without the deep investment of community engagement and review, new labels—like BIPOC—run the risk of causing more harm than good. Instead, we should continue to use the term “people of color” when referencing this group in comparison to whites, while “women of color” is useful when considering raceXgender intersectionality. Banding together for mutual support and action has been critical for people from marginalized identities as they have worked toward lasting social change. Additionally, it is often important to disaggregate data to report on individual groups that could otherwise get lost under these larger umbrella terms.

The experiences of various communities in law school help illustrate the point that academics, advocates, and allies should use be careful in their language usage—especially when dealing with data. Grouping populations together is often instructive. It can also be necessary to disaggregate the data to deal with separate communities individually. Law student debt and experiences with issues of diversity are particularly instructive in explaining both paths.

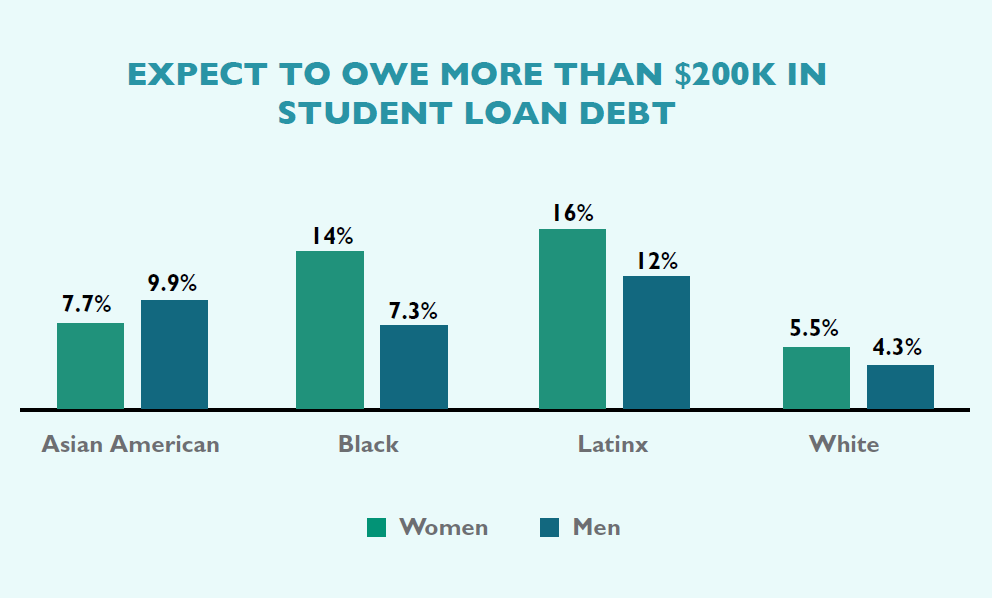

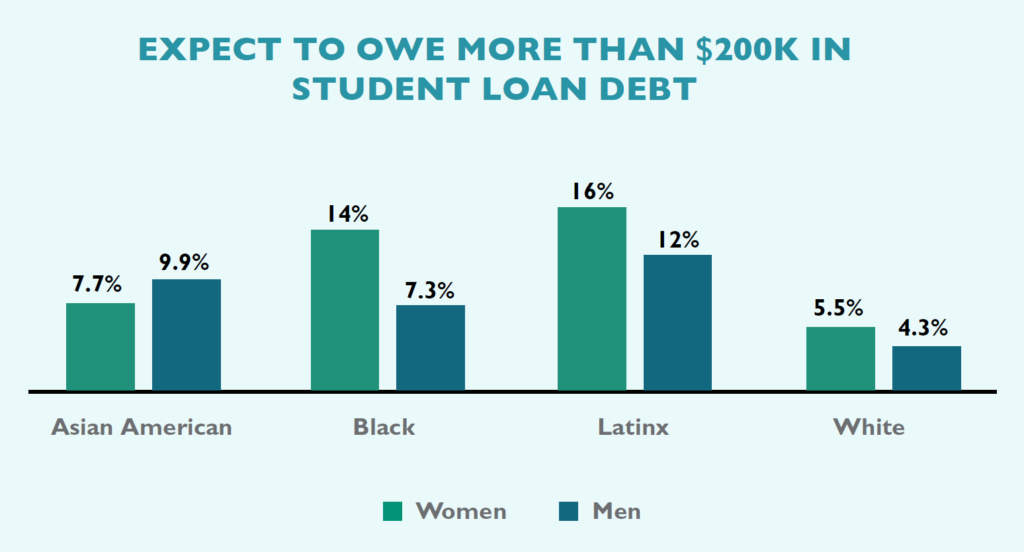

First, LSSSE data reveal that students of color carry more educational debt than white students. Here, it is appropriate and useful to group students of color together as a whole in comparing them with white students in terms of their overall debt loads. However, we can dig deeper to consider the intersectional experience of gender combined with race. If we ignore gender in this context, we run the risk of masking the distinct experiences of women of color compared with men of color as well as other groups. And there are differences. As I write in the article, “[H]igher percentages of Women of Color (23%) graduate with over $160,000 in law school debt, as compared with Men of Color (18%), white women (15%), and white men (12%).” While examining debt by raceXgender is thus more useful than considering race alone, being even more precise with the data and our language provides an opportunity to reveal more nuanced realities for communities within the women of color umbrella. As we share in our 2019 LSSSE Annual Report, The Cost of Women’s Success, the raceXgender groups most likely to carry the highest debt loads of over $200,000 are Latinas (16%) and Black women (14%), compared to lower percentages of Asian American women (7.7%), Black men (7.3%), Latino men (12%), and white men (4.3%). Thus, while it is correct to talk about the people of color and women of color carrying more debt than whites and those who are not women of color, it is more complete and sophisticated to explain how particular raceXgender groups—Black women and Latinas—have the highest debt loads of all. Precise racial language is instructive, particularly if we seek to craft solutions to ameliorate these challenges that are directly responsive to the needs of the populations affected.

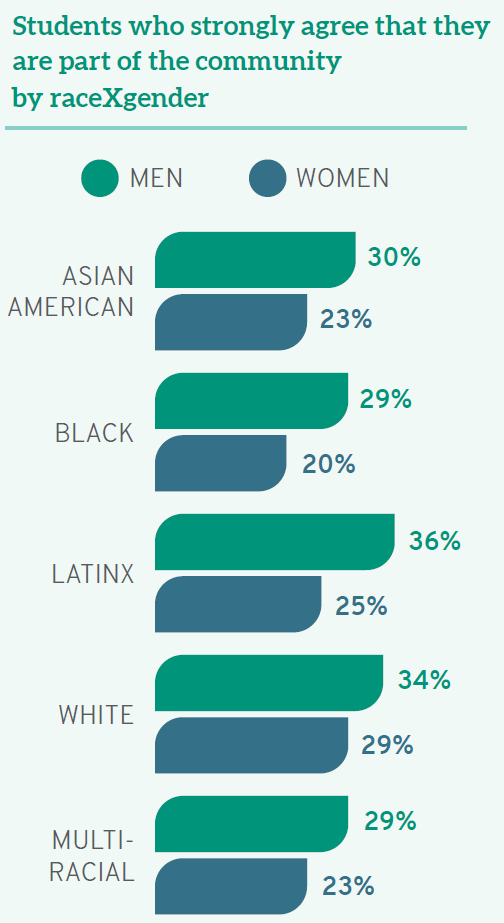

Student experiences with diversity provide another example of the benefits of careful language usage. Compared to their white peers, students of color have distinct opinions and experiences in law school when considering issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion. For example, although almost one-third (31%) of white law students “strongly agree” that they see themselves as part of the law school community, students of color are less likely to agree. As with debt levels, there are again additional distinctions based on raceXgender. In Better than BIPOC, I draw on data from the LSSSE 2020 Annual Report, Diversity & Exclusion, noting, “Fewer than one-quarter (23%) of women of color ‘strongly agree’ that they are part of the institutional community, compared to almost one-third (31%) of men of color.” Thus, distinctions based on race alone are not as precise as those disaggregating racial data by gender. In certain contexts, we also can—and should—go further still. By looking within the category of people of color, we can determine important differences between groups that administrators, faculty, and staff should consider in order to tailor solutions to the students who most need them. For instance, when we consider student belonging, “only 21% of Native American and Black law students see themselves as part of their law school community—compared to 31% of their white classmates, 25% of multiracial students, 26% of Asian Americans, and 28% of Latinx students.” Considering the student of color narrative as one group would tell an incomplete story as Black and Native law students are even more alienated nationally than even other students of color. Addressing their concerns will require us first to understand them, then to act.

Better than BIPOC also draws from the data behind my book project, Unequal Profession: Race and Gender in Legal Academia, to share examples from the law faculty context. I use findings on student evaluations and the challenges different populations face while navigating work/life balance to suggest when we should compare faculty of color as a whole to their white colleagues, when to disaggregate by race as well as gender to examine the experience of women of color faculty, and when to look more carefully within racial and gender-based categories to reveal important distinctions that could otherwise be hidden. Beyond the context of legal education, we can apply this thesis to frameworks as diverse as political engagement, workplace harassment, elementary school integration, diversity in corporate boards, and more. Different situations will naturally call for specific groups to be named and studied directly; that context, regardless of the terms currently en vogue, should drive the data used and arguments made in any endeavor. Working collectively serves a purpose, as does disaggregating the data. Through both efforts, we can understand the unique challenges facing different groups and work collectively to address them.

Engagement with Law Student Organizations

Law student organizations are important venues for developing law students’ professional identities. Through networking, invited speakers, and events, these organizations foster a sense of community and provide students the opportunity to more intensely explore areas of law that interest them. [1]

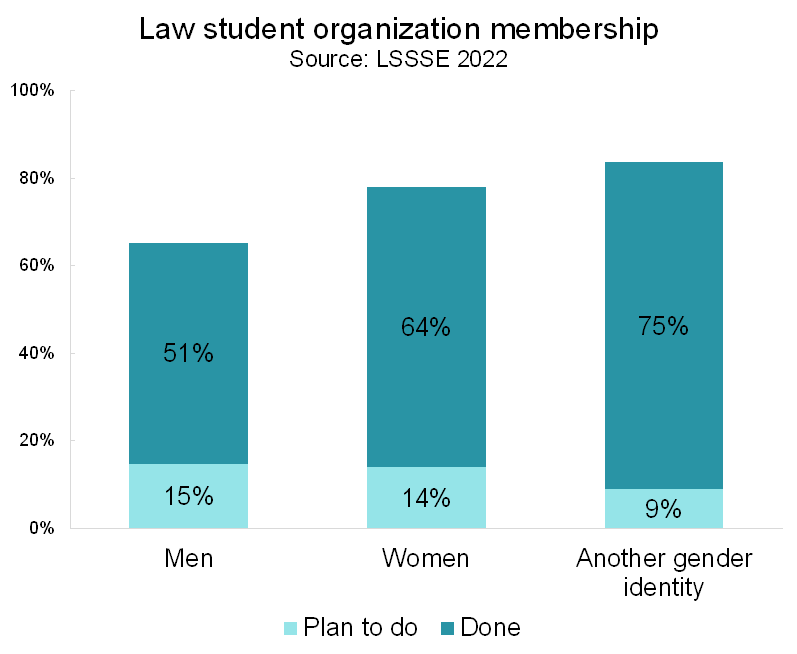

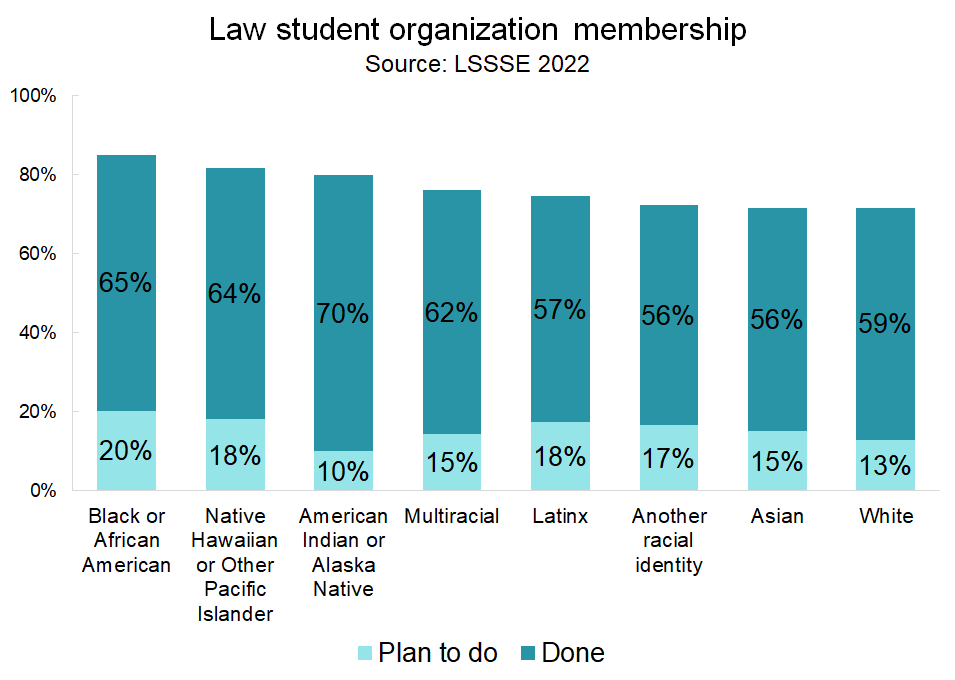

Law student organizations are among the most popular enriching activities at law schools. Nearly three-quarters (73%) of law students either plan to join a law student organization or have already done so. About 31% of students have served as law student organization leaders, and another 18% plan to take on a leadership role before they graduate. Men are less likely to join student organizations compared to women and those of another gender identity. In 2022, just 51% of men had already joined an organization compared to 64% of women and 75% of those with another gender identity.

Black students are particularly engaged as members of law student organizations, with 65% of Black students participating and another 20% planning to do so. Native Hawaiian students, American Indian students, and Alaska Native students have similarly high levels of engagement with law student organizations, while Asian and white students have the lowest participation rates.

Women, gender-diverse people, and students of color are most likely to join student organizations. Thus, these organizations likely play a vital role in connecting law students who traditionally face higher barriers in accessing higher education and assimilating successfully into the legal profession. Law student organizations also given students the opportunity develop their leadership skills and to work with their professors and classmates in a non-classroom context.

____

[1] See Andrew Hitt, The importance of student organizations, (Aug. 27, 2009), https://law.marquette.edu/facultyblog/2009/08/the-importance-of-student-organizations/

Part 2: The COVID Crisis in Legal Education: Concern about Meeting Basic Needs

In our last post, we used LSSSE longitudinal data that was first reported in our 2021 Annuals Results, The COVID Crisis in Legal Education (pdf), to discuss the areas of law student engagement that were most impacted by the COVID-related challenges of the 2020-2021 academic year. In addition to the intangible losses, COVID also deepened ongoing disparities and inequities in legal education, as it did in society more generally. Student populations that were especially vulnerable pre-pandemic faced even greater challenges over the past year. The crisis has been perhaps most critical when considering basic necessities, though every level of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs has been affected—from the essentials of food, rest, physical safety, and financial security to the desire for belonging, appreciation, and ultimately achieving one’s full potential.

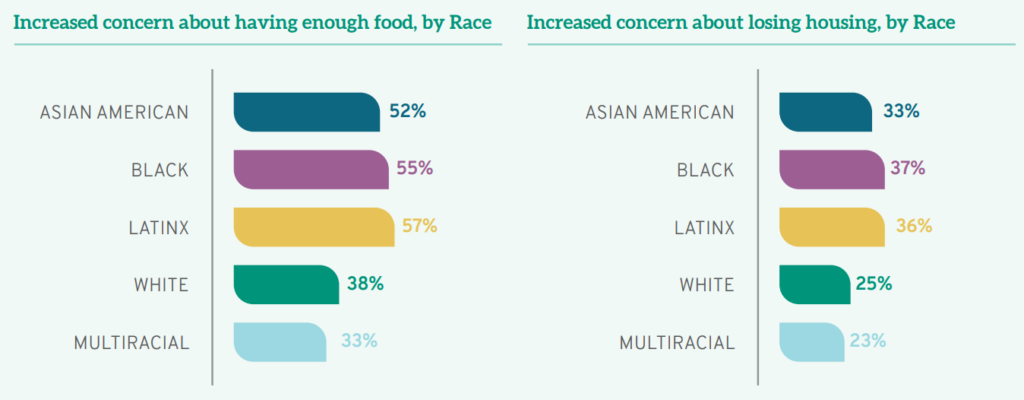

In 2021, many students struggled to meet their basic needs. In their responses to the LSSSE survey module Coping with COVID, 43% of all law students reported increased concern about having enough food due to COVID-19. This already troubling finding about students as a whole masks significant racial disparities with food insecurity: over half of all Black (55%), Latinx (57%), and Asian American (52%) students acknowledged that the past year brought increased concerns about whether they had enough food to eat.

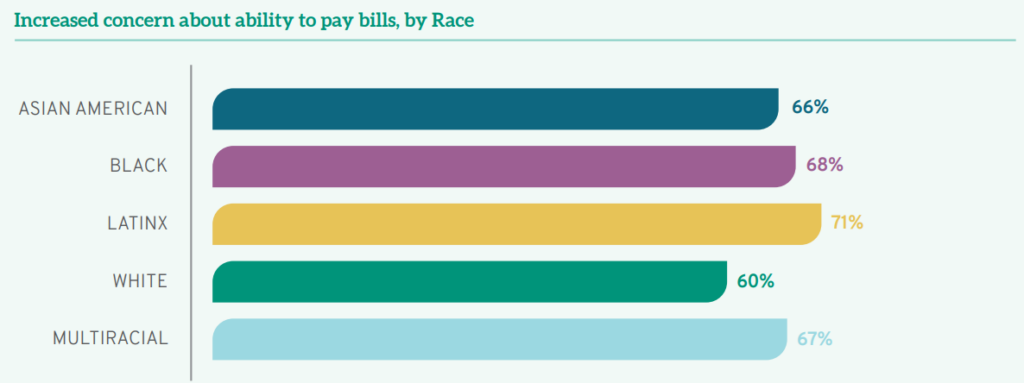

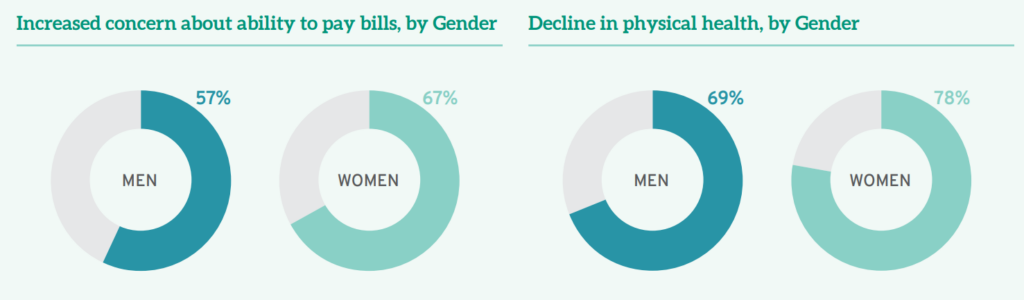

Financial concerns weighed heavily on students’ minds. Almost two-thirds (63%) of all student respondents had increased concerns about their ability to pay their bills, with both gender and race-based disparities increasing challenges for already vulnerable populations. For instance, among those who had elevated concerns about their financial security were 71% of Latinx students, 68% of Black students, 67% of multiracial students, and 64% of Asian Americans, compared to 60% of White students. Additionally, while over half of the men (57%) worried that the pandemic would affect their ability to pay their bills, over two-thirds of the women respondents (67%) faced similar financial uncertainty; a full 14% of women students reported that their financial fears had increased “very much,” compared to only 6% of men reporting that same high level of concern.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given elevated attention to satisfying basic needs like food, shelter, and financial security, as well as the realities of the pandemic, 75% of all law student respondents also reported increased concerns about their own health and safety, while 84% were also more worried about the health and safety of friends or family. A full 75% reported a decline in their own physical health over the past year, though men fared better in this regard: two-thirds (69%) of all men surveyed noted a decline in their physical health compared to over three-quarters (78%) of women law students.

Legal education has survived what were hopefully the deepest lows of the COVID-19 pandemic. But we did not emerge unscathed. The core of legal education continued as before—the basics of teaching and learning pivoted from in-person to online, professors successfully conveyed care and concern along with doctrinal analyses, and student satisfaction levels remained remarkably high. Yet just as in other aspects of our lives this past year, legal education lost much of its depth and flavor. It has been less fulfilling, less comprehensive, less effective at imparting the intangible skills our students will need to employ in their future careers. Most critically, the Coping with COVID Report (pdf) reveals that our students have been struggling beyond anything they have experienced collectively before.

Law Student Leisure Time, 2004-2020

Law students need time to rest and recharge. Amidst questions about how much time law students spend working, preparing for class, commuting, and participating in extracurricular activities, LSSSE also asks about time spent on leisure activities such as reading, relaxing and socializing, and exercising. Here, we look at trends in leisure activities from 2004 to 2020.

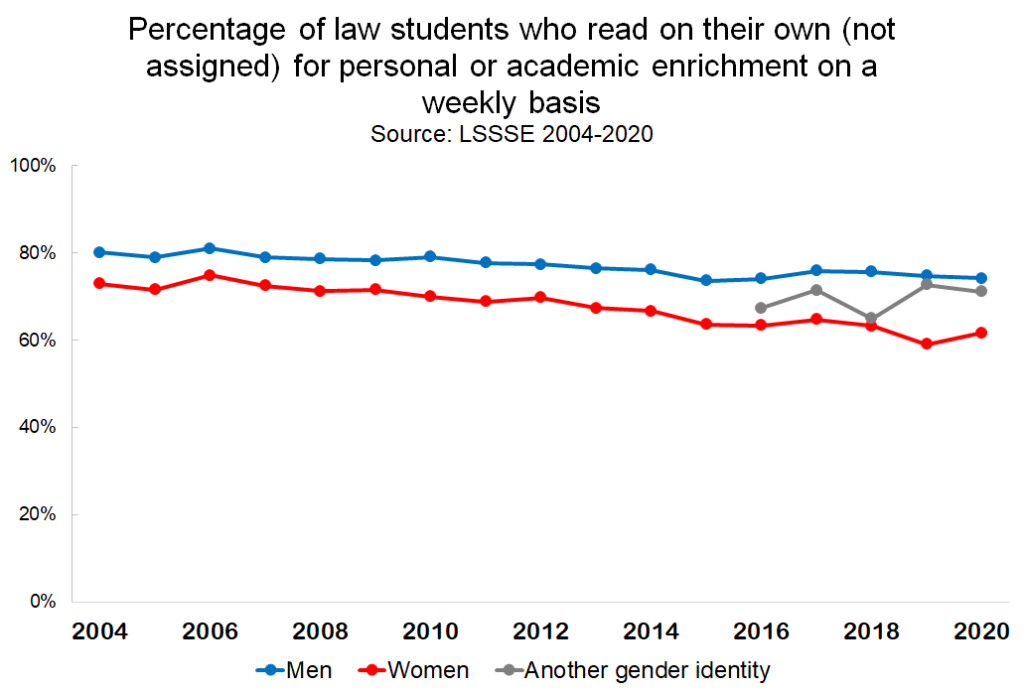

Most law students read on their own for personal or academic enrichment for at least one hour per week. However, the percentage of students who spend time on non-assigned reading has decreased gradually over the last decade and a half. Across every year studied, more men than women spend time reading for personal enrichment, and the gap has widened in the last few years. In 2004, 80% of men and 73% of women read on their own for at least an hour per week. In 2020, those numbers were 74% of men and only 62% of women.

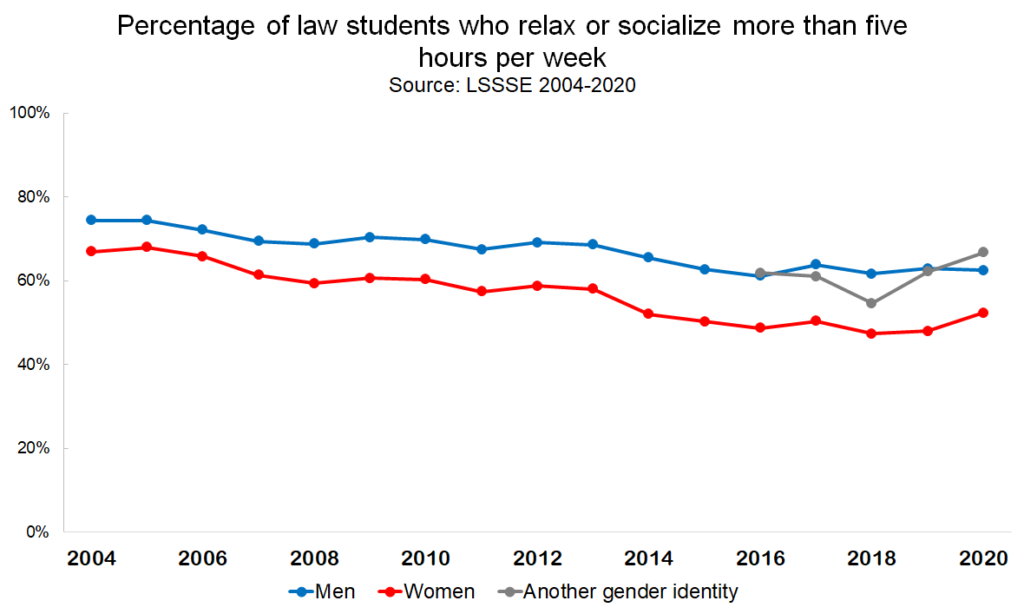

These trends toward a) decreasing time spent on leisure and b) more men than women engaging in leisure activities also hold true for time spent relaxing and socializing. The percentage of law students who relax or socialize for more than five hours per week (which is about an hour per day) has decreased from 71% in 2004 to 56% in 2020. Female law students are less likely to have time to relax. About half of female law students (48%) spent fewer than five hours per week relaxing and socializing in 2020, compared to only 37% of their male counterparts.

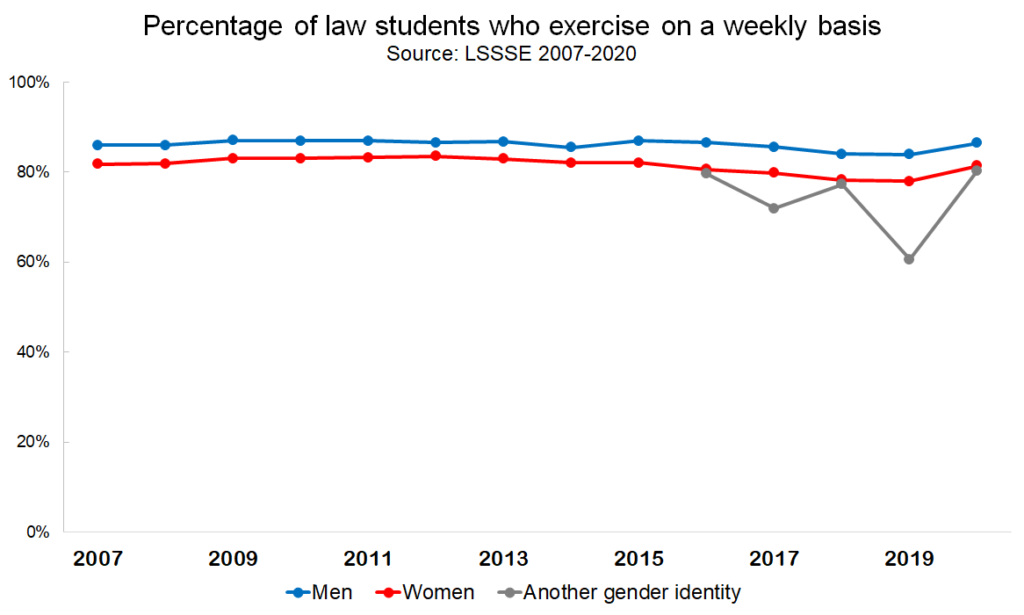

Fortunately, law students continue to make time for physical activity. Slightly more than eighty percent of law students exercise on at least a weekly basis, a number that has remained fairly constant since 2007, when the question was first added to the survey. Again, men are more likely than women to make time for exercise, although the disparity is not as great as it is for relaxing/socializing and for reading. This may suggest that when law students of all genders need a break from the sedentary work of reading and studying, they turn to physical activity to blow off some steam.

Guest Post: Legal Education and the Illusion of Inclusion

Guest Post: Legal Education and the Illusion of Inclusion

Shaun Ossei-Owusu

Shaun Ossei-Owusu

Presidential Assistant Professor of Law

University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School

A new semester and a potentially new political landscape are upon us. Last month law students around the country resumed coursework. Their educational pursuits are virtual, in-person, or some mix of both. No matter the format, law students continue their educational journey in an ideologically polarized pandemic society where race, class, and gender disparities are on sharp display.

Students will also be learning in a context where changes in our legal system may have direct relevance to their legal education. As is typically the case, a newly constituted Supreme Court has a diverse docket this term that might shape substantive areas of law that students take courses in, chiefly constitutional law. There will be regulatory shifts that come with new administrations. These kinds of changes will have meaning for administrative law and related areas of law: health law, environmental law, employment law, and civil rights, to name a few. COVID-19 has upended state and federal judiciary systems in ways that have still-undetermined implications for procedural courses law students take (e.g., evidence, civil procedure, criminal procedure) and access to justice issues more generally. And we know from the late Deborah Rhode’s work which communities access to justice issues tend to devastate—racial minorities, women, and other marginalized populations.

Notwithstanding future uncertainty, one thing can be said with some measure of confidence: issues of race and gender—amongst other social categories—will remain relevant inside and outside the sometimes intellectually-cordoned off walls of law schools. How these issues are integrated in the classroom, if they are at all, will affect the substantive learning of law and will either include or exclude historically marginalized groups.

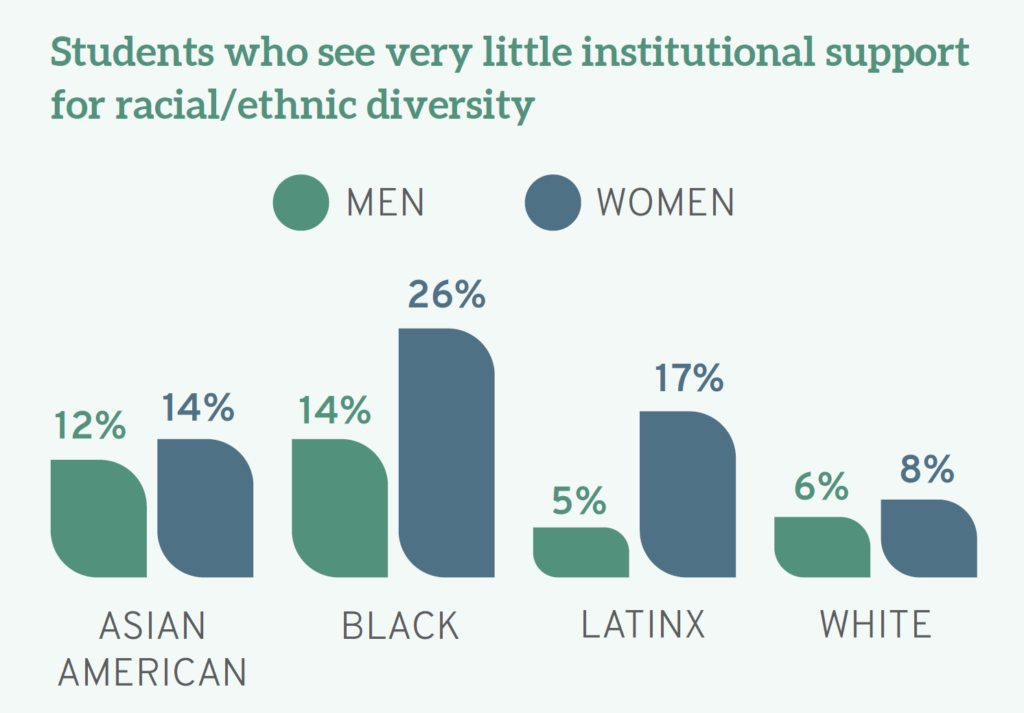

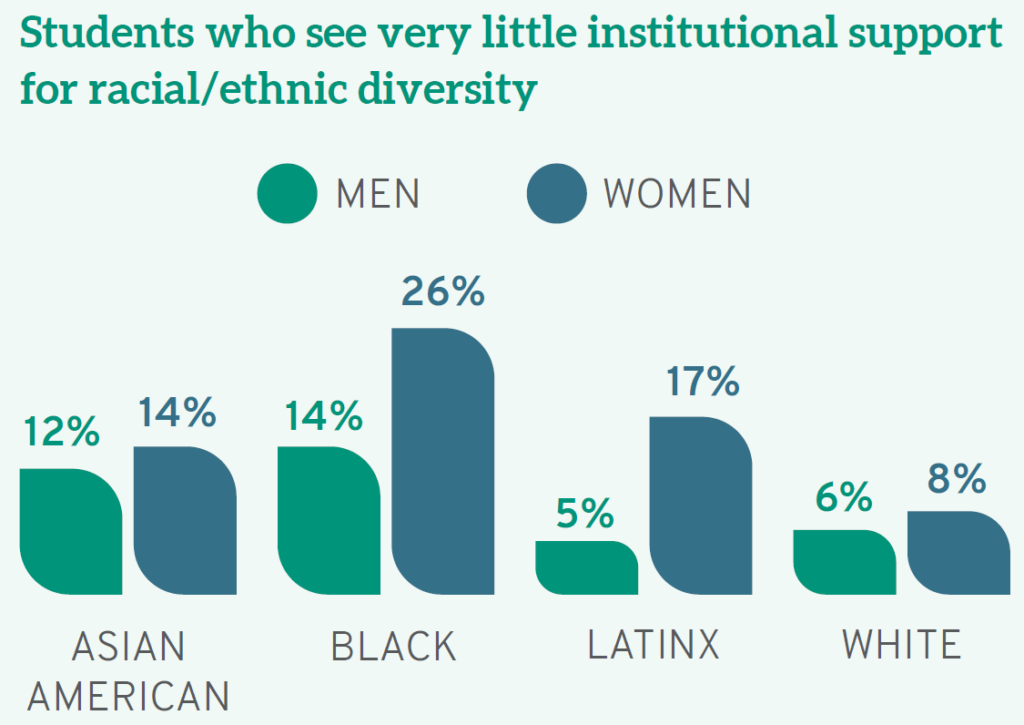

In the specific context of legal education, the results of Law School Survey of Student Engagement’s (LSSSE) Annual Survey illuminate. The Report provides a glimpse into how law schools fail to meet the aspirational goal of inclusion that often takes up primetime real estate on their websites and promotional materials. From my own read, the most jaw-dropping finding is intersectional in nature and about Black and Latinx women law students—aspiring attorneys who are often told that they do not look like lawyers when they transition to practice. 26% of Black women respondents and 17% of Latinx women respondents reported that their schools do “very little” to support racial and ethnic diversity.

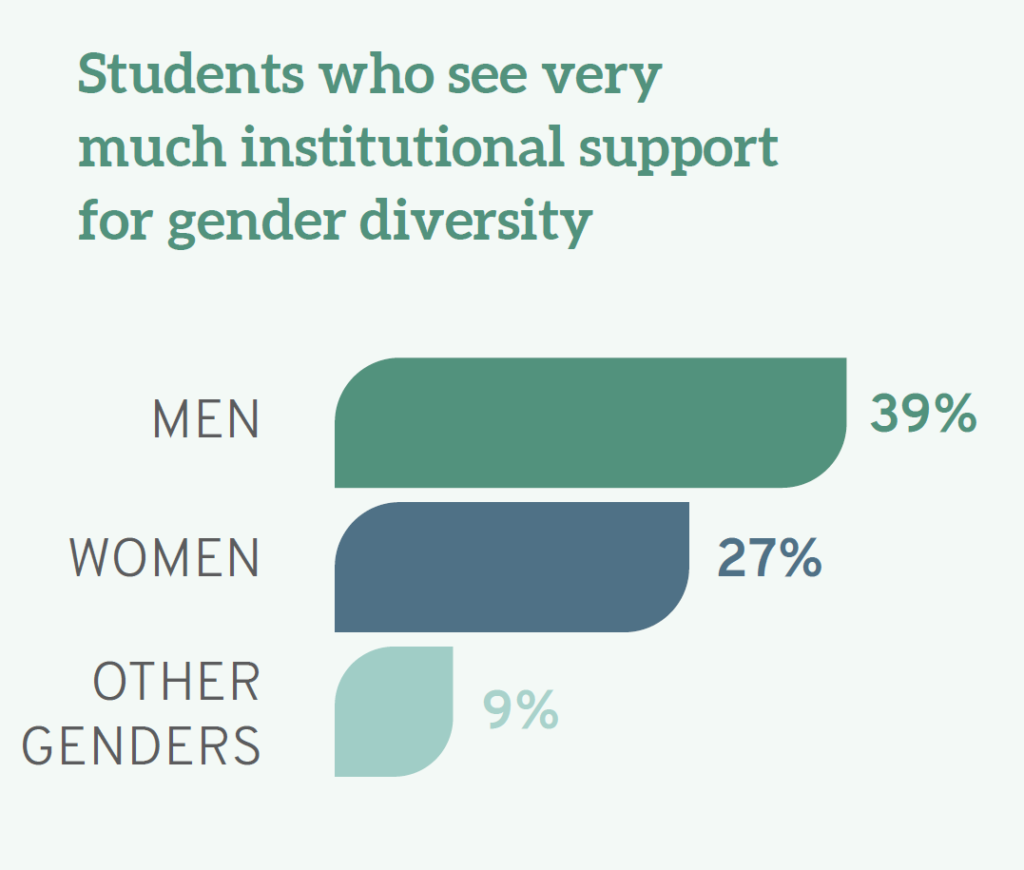

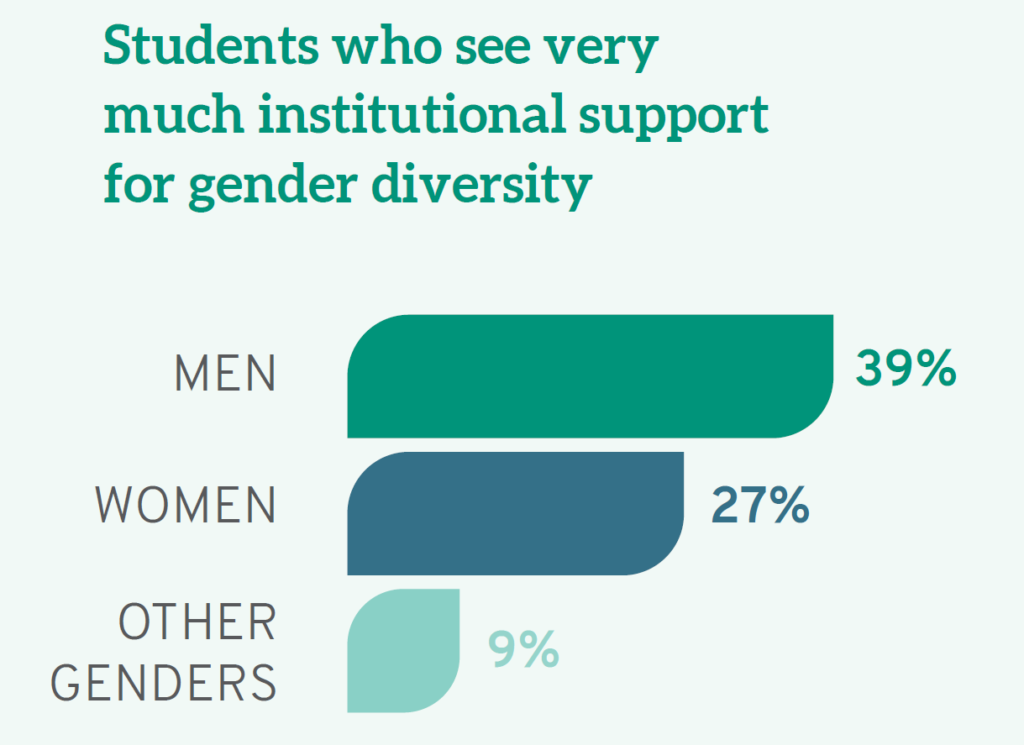

Disenchantment with the lack of support for diversity can be distilled even further. The Report notes that men varied on the issue of gender inclusivity, with 39% “very much” believing that their schools support gender diversity compared to 27% of women and 9% of individuals who identified with the “other gender” category.

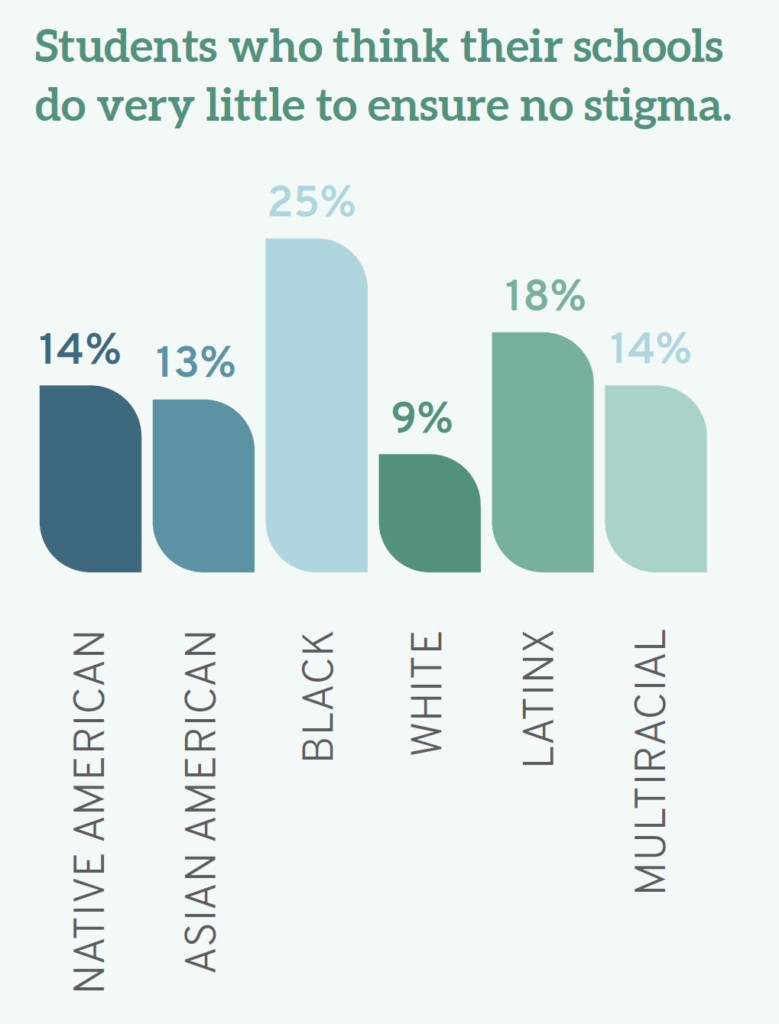

In the context of race, student views also differed, with 9% of White students, 14% of Native American students, 18% of Latinx students, and 25% of Black students believing that their schools do “very little” to ensure that students are not stigmatized based on identity.

Where sexuality and sexual orientation are concerned, 11% of heterosexual students think their schools do only “very little” to avoid identity-based stigma; conversely, 20% of gay students, 16% of lesbian students, 15% of bisexual students, and 19% of those who identify as another sexual orientation see their schools as doing “very little” in this regard. What do these findings mean for legal education and the political moment I gestured to in the beginning?

LSSSE’s data suggest that some students are dissatisfied with the six-figure education they are receiving. Put plainly, law students from backgrounds that the profession has historically excluded—women, racial minorities, LGBTQ communities, and people with disabilities in particular—do not feel part of the academic community and believe law schools are relatively disinterested in their stigmatization. In some ways, this is unsurprising, as there is a deep scholarly literature and genre of books on student disappointment with law school. Moreover, student disenchantment with legal education—which has a history of exclusion that traces back to the nativism and anti-Semitism of the early twentieth century—may in some ways be pre-determined.

The confines of the classroom, which is one of the many areas the LSSSE survey discusses, provides more insight into the inclusion-exclusion dyad. From the vantage point of some educators, law school is simply about training people to be lawyers. The most generous reading of this position suggests that social justice-like ideas like “inclusion” are too ideologically weighty to meaningfully bring in the classroom. For people who subscribe to this view, attempts at inclusion can create impossible-to-navigate landmines for professors. More skeptically, some see inclusion as an ancillary. Read in this light, the primary goal is to inculcate legal knowledge. For these professors, some things are not relevant to the practice of law and are therefore not relevant to legal education.

Such professional school-based views of legal education, vary in their reasonableness, but are held by swaths of the professoriate. Yet, there is a two-fold problem, and this is where the LSSSE survey is especially useful. First, this vision of legal education rubs up quite abrasively against the representations of law schools as bastions of inclusion. Second, this version of education, in some ways, undermines the well-touted “diversity rationale” in affirmative action jurisprudence. What does diversity mean when the subjects of diversity feel alienated?

Considering the mismatch between some students’ experiences and the stricter professional school model of legal education that some professors are beholden to, there are some options. Educators can simply be more intellectually honest about the reality that law school is a site of professionalization where inclusion principles can be trivialized. Alternatively, law schools can continue to disingenuously hitch the law school wagon to social justice rhetoric while failing to actualize inclusion as a practice. Or, in the most courageous and imaginative versions of themselves, law schools can refashion their curriculum and use developments in the legal world as opportunities to offer more inclusive learning environments.

For law schools committed to the third way, resources abound. Complaints about the need to diversify the content of law school courses have existed for decades. Scholars such as Derrick Bell and Dorothy Brown have authored casebooks that describe how race intersects with different areas of the legal curriculum, whereas feminist legal theorists, poverty researchers, scholars of law and sexuality have penned their own books, supplements, and articles that all give educational guidance on how to bring these issues into core courses, and do so in ways that are doctrinally sound. Still, some professors—many of whom have the most analytically sharp minds on their university campuses—throw their hands up in despair or continue with the same regularly scheduled program. For some of these instructors, these conversations were absent in their legal education, and they were likely not trained to incorporate these issues. Some may think it would be better to leave this work of thematic inclusion to their more expert colleagues (e.g., scholars of race, sex, class, disability) rather than wade into territory where they are sure to mess up. But throwing one's hands up in despair is increasingly a less credible course of action. The pandemic, along with the protests of 2020, have forced some people to rethink how they deliver course content, and more importantly, have made inequality a more prominent theme in our public discourse. The current socio-political moment, and the reality of pandemic pedagogy, call for curricular redesign.

Fortunately, the tools to make the classroom more inclusive are available and they are not limited to the usual courses. To be sure, law professors have written about how first-year courses like criminal law and property are inattentive to inequality in ways that produce the responses found in the LSSSE survey and have offered suggestions on how those same courses could easily be improved. But attempts to diversify and create a more inclusive curriculum are not confined to these foreseeable areas of law but can be found in more unsuspecting places like evidence, corporate law, trust and estates, and intellectual property, to name a few.

Law professors have also identified space in the curriculum for trans-substantive engagement with the kinds of questions and perspectives that demonstrate an awareness of inequality, both in legal education and in law more generally. Indeed, I, along with my colleague Karen Tani, have taken on the task of trying to simultaneously create an inclusive learning environment that rigorously addresses inequality by creating a 50-person Law and Inequality course at Penn Law. This endeavor and more meaningful engagements with diversity need not be limited to women, racial minorities, and sexual minorities. Inclusion also implicates and has meaning for the larger law student population. One of the most understated findings in the LSSSE Report is that 16 percent of white students believed law schools placed “very little” emphasis on issues of equity and privilege and do not prioritize providing students with the skills necessary to confront discrimination and harassment.

My purpose here is not to proselytize teaching a course like the one we are offering. Instead, I want to highlight how student dissatisfaction with inclusion, which the Report highlights in detailed and accessible fashion, can be situated within this critical juncture. 2021 is a unique moment where law schools can reimagine legal education in real time, and for a post-pandemic world. This will not be easy, as this is a stressful time for faculty—some of whom are in high-risk groups during the pandemic and/or have a variety of care obligations. COVID-19 has upended a lot of assumptions and forced people to change longstanding pedagogical practices. Institutions could do a lot of good by encouraging faculty reflection and supporting creative reorganization of current courses.

The LSSSE Report tells us that in many ways, law schools are failing to provide the inclusive educational spaces that they, I believe in good faith, want to offer and that students of various backgrounds actively desire. Ultimately, the teaching tools are available, the moment is ripe, and the only outstanding question is whether legal educators will make the changes necessary so that the next LSSSE survey offers more optimistic findings.

Annual Results 2020 Diversity & Exclusion: Institutional Support for Diversity

This year for the first time, LSSSE introduced a set of questions focused on diversity and inclusion that supplement related questions from the primary survey. The Diversity and Inclusiveness Module examines environments, processes, and activities that reflect the engagement and validation of cultural diversity and promote greater understanding of societal differences. The 2020 LSSSE Annual Results Diversity & Exclusion report presents data about how diversity in law school can prepare students for the effective practice of law upon graduation. In our next three posts, we will highlight key findings from the report and suggest some areas for improvement.

Support for diversity in law school must begin with the institution. Yet many students of color do not see their campus as supportive of racial/ethnic differences. Almost a quarter (23%) of Black law students nationwide say their schools do "very little" to create a supportive environment for race/ethnicity, compared to just 6.8% of White students. At the opposite end of the spectrum, 32% of White students believe their schools do "very much" to support racial/ethnic diversity, compared to only 18% of their Black classmates. Men (37%) are also more likely than women (26%) and those of another gender identity (7.5%) to believe their campus is very supportive of racial/ethnic diversity. Even more dramatic are intersectional identity findings, as a full 26% of Black women— more than any other raceXgender group—see their schools doing "very little" to create an environment that is supportive of different racial/ethnic identities, as compared to just 5.5% of White men (while 72% of White men believe their schools do "quite a bit" or "very much" in this arena).

Men are also more likely to see their campus as a "supportive environment for gender diversity," with 39% believing this "very much" as opposed to 27% of women students, and only 9% of students who identify as another gender identity. Furthermore, White students as a whole (33%) see the campus as very supportive of people of different genders, compared to 21% of Native Americans and Black students. Again, the views of White male students differ significantly from most others with a full 40% seeing their campus as very supportive of gender difference. In short, women as well as others from less privileged groups do not see their schools as particularly supportive of gender inclusivity.

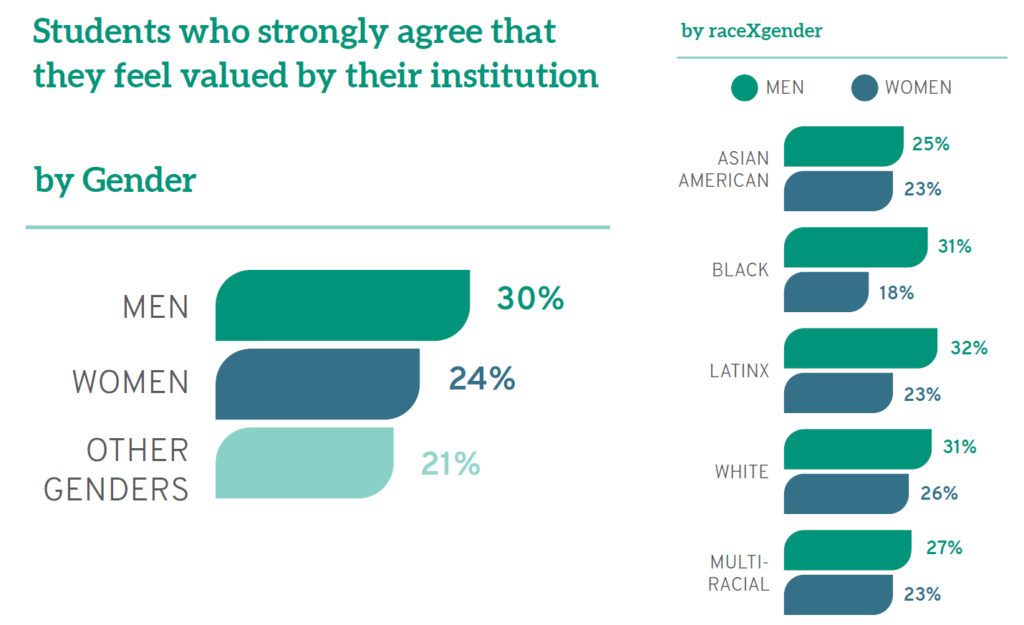

Not surprisingly, given the relative lack of support they see for racial/ethnic and gender diversity on campus, women and students of color also believe their schools are less invested in them as individuals. When asked whether they "feel valued" by their law school, a full 30% of men "strongly agree" compared to only 24% of women and 21% of those who identify as neither male or female. Similarly, the racial/ethnic group most likely to "strongly agree" is Whites (28%). In fact, while Latinos, White men, and Black men "strongly agree" that they are valued at roughly equal rates, men feeling more valued than women is consistent across every racial/ethnic group. Furthermore, students who are the first in their families to earn a college degree, often called "first-gen" students, feel less valued by their institution: a full third (33%) note they do not feel valued, compared to a quarter (25%) of others, which is also a significant proportion of law students overall.

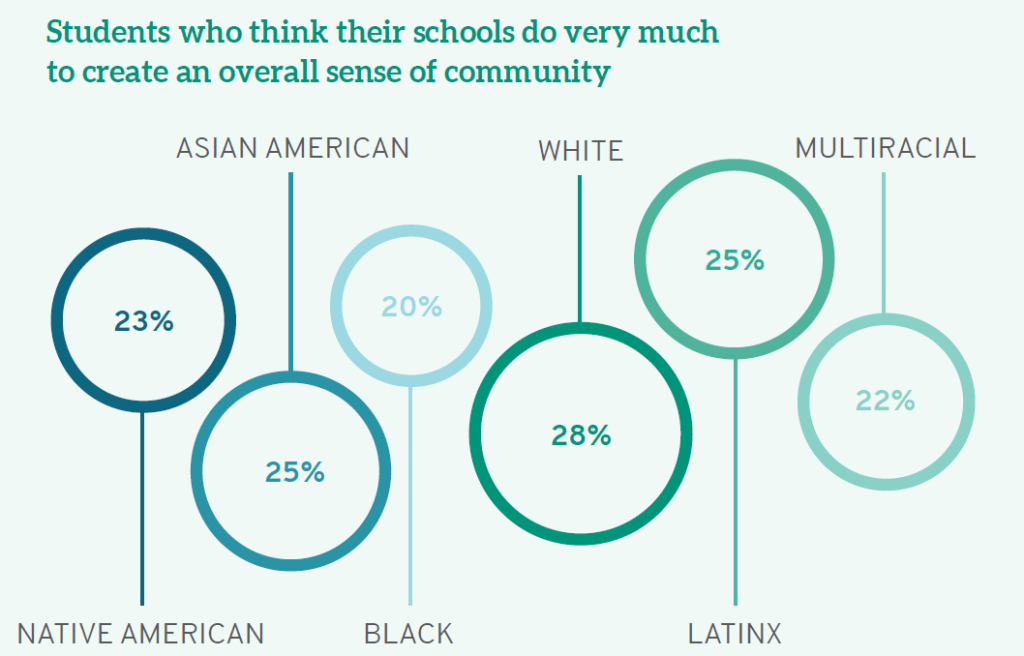

Institutions can put mechanisms in place to foster community among those on campus, regardless of their background or experiences. Finding this common ground helps all students understand that they belong and that others who may be different should be equally welcome. Again, White students are most likely to believe their institution emphasizes the importance of "creating an overall sense of community among students." While 28% of White students think their schools do this "very much," smaller percentages of students of color feel similarly. Even more disheartening, 18% of Black students and 14% of Latinx students think their schools do "very little" to foster community.

Many law schools have made concerted efforts to add student diversity to their campuses. But once students enroll, we owe it to them to provide a safe and welcoming environment, one where they feel valued, where they can be themselves, where they acquire the tools they need to succeed in the workplace, and where they can thrive. Admitting and even enrolling more students of color, first-gen students, students who identify as LGBTQ, and women is not enough unless that diversity is accompanied by inclusion. Law schools that want their students to succeed as future lawyers and leaders must commit to fostering a campus community where the most vulnerable and non-traditional are encouraged to reach their full potential, where faculty are expected to train students not only for the global marketplace but for the realities of American life, and where all students appreciate their own backgrounds, biases, and responsibilities to the profession.

LSSSE Annual Results 2019: The Cost of Women’s Success (Part 4)

The Troubling Secret to Success

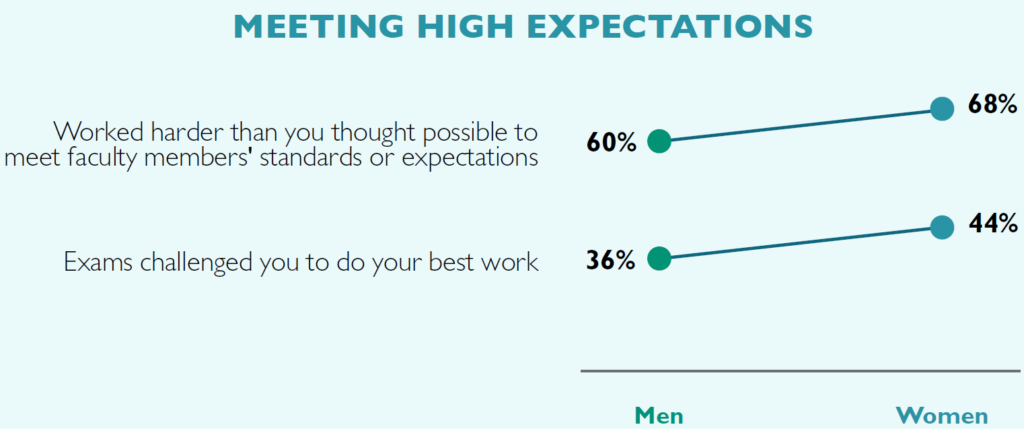

What is the secret to the success of female law students? They enter law school with fewer resources and amass significant burdens once enrolled, but perform at equal or higher levels than their male peers along many metrics. The data suggest one clear answer: women law students work extraordinarily hard, juggling their various personal and academic responsibilities at the expense of self-care. While most students work hard to meet the high expectations of their professors, women students report sustained effort at higher levels than their male peers. A full 68% of women note that they “Often” or “Very Often” worked harder than they thought they could to meet faculty members’ standards or expectations, compared to 60% of men. Similarly, higher percentages of female students than male rise to the challenge of submitting their best work on exams. LSSSE respondents were asked to report “the extent to which your examinations during the current school year have challenged you to do your best work” on a 7-point scale. Remarkably, 44% of women report the highest level of engagement (a 7 out of 7) as compared to 36% of men. Again, these findings of hardworking women are consistent across race/ethnicity.

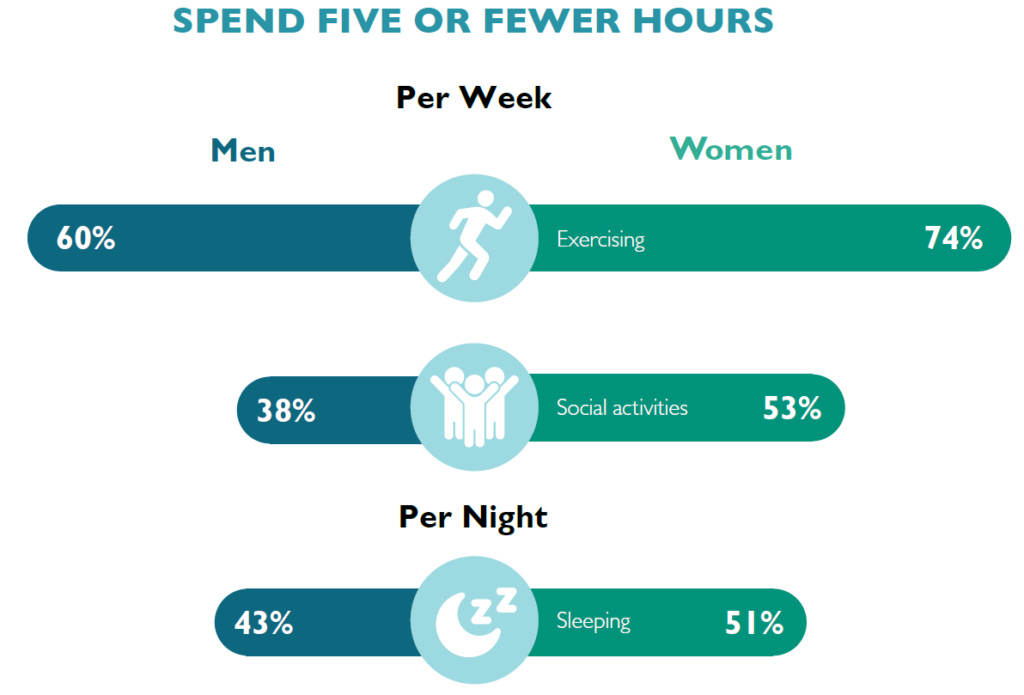

Tragically, the hard work that women dedicate to enabling their success comes at a significant cost. The tradeoff is that women are much less likely than men to engage in important social, leisure, and self-care activities. Each of these findings is consistent across racial/ethnic groups when comparing women with men. For instance, 41% of women spend zero hours per week reading for pleasure, compared to 25% of men. Similarly, the overwhelming majority of women law students find little time for physical fitness, with 74% reporting that they exercise no more than 5 hours a week (along with 60% of men). Expanding this concept to other leisure activities—including watching TV, relaxing, or even partying—does not improve this gender disparity. More than half (53%) of women law students spend five or fewer hours per week engaged in any of these social activities, compared to just over a third (38%) of men. Furthermore, half (51%) of women report sleeping five or fewer hours per night in an average week, along with 43% of men. In the scramble to get ahead academically, women are overlooking downtime; they are prioritizing their academic success at the expense of their own wellbeing. Such limited opportunities to disconnect from schoolwork, engage in physical fitness, rest, relax, and socialize with others can have serious implications for the long-term physical and mental health of women law students.

For more in-depth analysis about gender disparities in legal education, you can read the entire LSSSE 2019 Annual Results The Cost of Women’s Success (pdf) on our website or contact us.

LSSSE Annual Results 2019: The Cost of Women’s Success (Part 3)

Opportunities for Improvement

Given the many challenges facing women upon entry to law school, it is no surprise that there are also opportunities to improve the experience for women students in legal education. LSSSE data on concepts as varied as classroom participation, caretaking, and debt make clear that women need greater support.

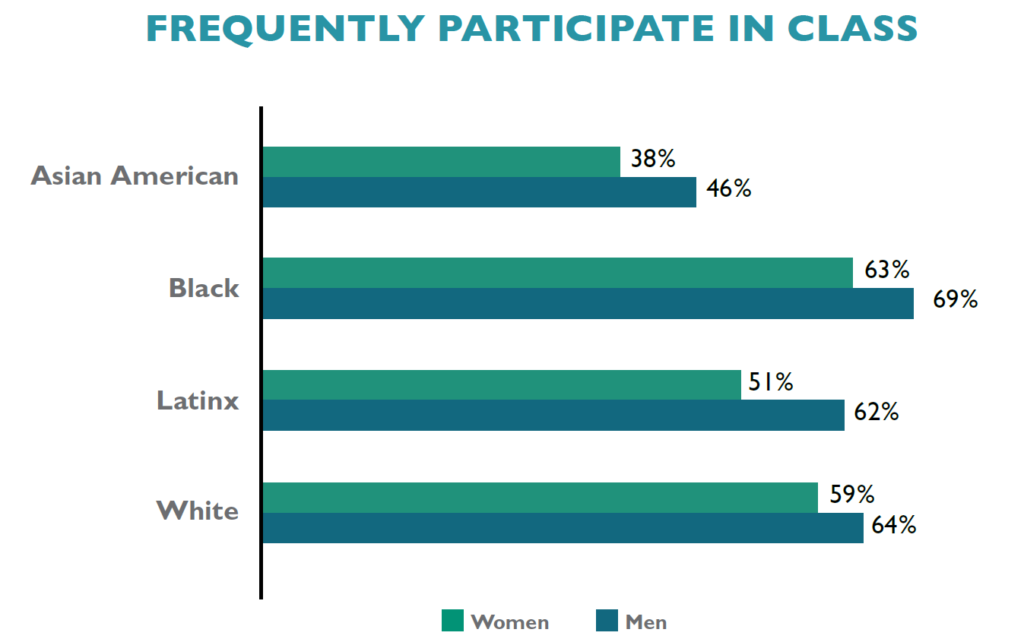

Engagement in campus life is an especially significant indicator of success. Law students who are deeply invested in both classroom and extracurricular activities tend to maximize opportunities for success overall. As stated in a previous post, women are just as likely as men to be involved in various co-curricular endeavors. Yet, smaller percentages of women than men are deeply engaged in the classroom. While 64% of men report that they “Often” or “Very Often” ask questions in class or contribute to class discussions, only 58% of women do. This gender disparity remains pronounced within every racial/ethnic group, as men participate in class at higher rates than women from their same background. There are also interesting variations by raceXgender, with Black men frequently participating at higher rates than any other group (69%), and at almost twice the rate of Asian American women (38%).

Many women students also spend numerous hours during their law school careers providing care to household members. For instance, 11% of women report that they spend more than 20 hours per week providing care for dependents living with them, as do 8.6% of men. These competing responsibilities require a significant investment of time, which could otherwise be spent on studying for class, working with faculty on a project outside of class, or even engaging in leisure activities. Instead, these students are taking care of their families.

An especially troubling discovery is that high percentages of women than men incur significant levels of debt in law school. Among those who expect to graduate from law school with over $160,000 in debt are 19% of women and 14% of men. This gender difference remains constant within every racial/ethnic group. Even more alarming is the disparity among those carrying the highest debt loads: 7.9% of women will graduate from law school owing over $200,000 as compared to 5.5% of men. LSSSE data not only confirm existing research on racial disparities in educational debt, with people of color and especially Black and Latinx students borrowing more than their peers to pay for law school, but also reveal that women carry a disproportionate share of the debt load as compared to men. Furthermore, when considering the intersection of race/ethnicity and gender, we see that women of color specifically are graduating with extreme debt burdens.

Next week, we will conclude this series with some troubling trade-offs that women make to overcome the disadvantaged position in which they often find themselves relative to their male counterparts. You can read the entire LSSSE 2019 Annual Results The Cost of Women’s Success (pdf) on our website.