Guest Post: From Candidate to Law Student: Collaboration and Collective Efforts to Support LGBTQ+ Inclusion

Guest Post: From Candidate to Law Student: Collaboration and Collective Efforts to Support LGBTQ+ Inclusion

Elizabeth Bodamer, J.D., Ph.D. (she/her/ella)

Director of Research

Law School Admission Council, Inc. (LSAC)

Judi O'Kelley, J.D. (she/her/hers)

Chief Program Officer

National LGBTQ+ Bar Association (LGBTQ+ Bar)

The 2022 matriculant class in law school today is the most diverse class in the history of legal education. We have made progress, but there is more work to be done.

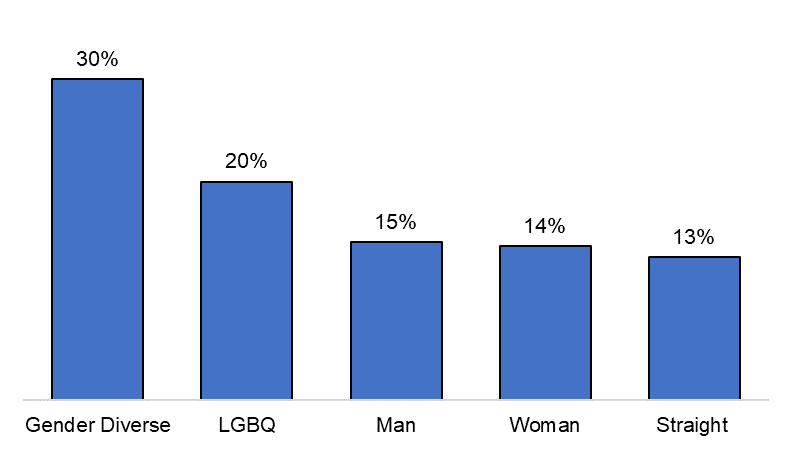

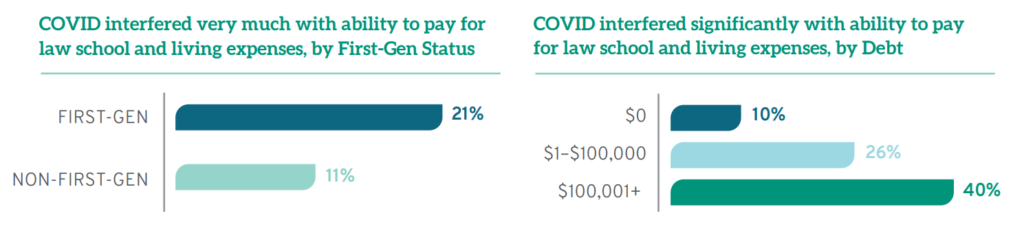

Diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts are needed not just at the admission stage, but throughout the prelaw-to-practice pathway. Law schools play a crucial role in creating an effective and supportive learning environment is important for everyone, particularly for LGBTQ+ students. LSSSE data shared in a blog post last year reveal that gender diverse and LGBQ law students were more likely than cisgender and straight students to report not feeling comfortable being themselves at their law schools.

Figure 1: Students Reporting Not Feeling Comfortable Being Themselves

Source: Data from the 2020 Law School Survey of Student Engagement Diversity and Inclusiveness Module. Data collected from over 5,000 law students across 25 law schools. LGBQ students represented about 14% of the sample and gender diverse students represented 1% of the sample.

It is within this context that LSAC and the LGBTQ+ Bar have worked to provide candidates, students, and law schools with data about the experience of LGBTQ+ students in addition to information about the availability of LGBTQ+ inclusive policies, practices, supports and resources.

Surveys administered by LSAC and by the LGBTQ+ Bar have found that schools are making progress in supporting LGBTQ+ applicants, students, faculty and staff. For example, the LGBTQ+ Bar found that that 99 participating schools (96.1% of survey participants) self-report that they allow transgender and nonbinary students who have not legally changed their names to have their name-in-use reflected on applications and forms. This is a positive change from a number of years ago. The next stage of inquiry is whether schools are implementing these policies and practices in a way that improves the student experience. LSAC found that of the 110 schools who responded to their question about chosen name usage:

- 67% reported that students’ chosen names automatically appear on their orientation name tags and/or materials.

- 49% reported that students’ chosen names automatically appear on faculty class rosters, 41% reported that this action requires students to submit a request, and 5% reported that students’ chosen names cannot appear on faculty class rosters.

- Only a very small proportion of schools indicated that students’ chosen names automatically appear on their transcripts (15%) and diplomas (14%).

- Almost 40% of schools reported that students’ chosen names cannot appear on transcripts that can be sent to employers.

- Almost one-third of the schools reported that students’ chosen names cannot appear on their diploma.

Woven together, the work done by the LGBTQ+ Bar and LSAC reveal that while progress has been made in creating a more inclusive experience for LGBTQ+ students, there are areas for growth.

Supporting the LGBTQ+ community in legal education takes a collective effort. Today, we know that according to LSAC data, about 0.6% of the 2022 matriculant class self-identified as transgender, gender nonbinary, or genderqueer/gender fluid, and about 14% of the 2022 matriculants identified as LGBQ+ (i.e., not straight/heterosexual). We expect these numbers to continue to grow given the latest 2022 Gallup report that about 1 in 5 Gen Z adults identify as LGBTQ+. To support this new class and all future law students, LSAC and the LGBTQ+ Bar are collaborating to administer a joint 2023 LGBTQ+ survey to law schools. The goal is to combine our efforts to build on our robust resources and insights for applicants, current law students, and schools. In order to have impact, we must work together.

Guest Post: The Importance of Supporting First-Generation Law Students

Melissa A. Hale

Melissa A. Hale

Director of Learning for Legal Education

Law School Admission Council

Today is First-Generation Student Day[1]! So, to celebrate, I want to talk about why we should support first-generation law students, and how we can do that.

Who are first-gen students? Although definitions vary and self-identification is important, a first-generation student is typically one whose parents or legal guardians have not completed bachelor’s degrees [2]. First-generation students are an important part of diversity, equity, and inclusion. However these students are often overlooked when discussing DEI goals. In fact, when I started law school[3], I’m not even sure the term “first-generation student” was being used, or if it was in some circles, students certainly weren’t recognizing the term or identifying as “first-gen” the way they are now.

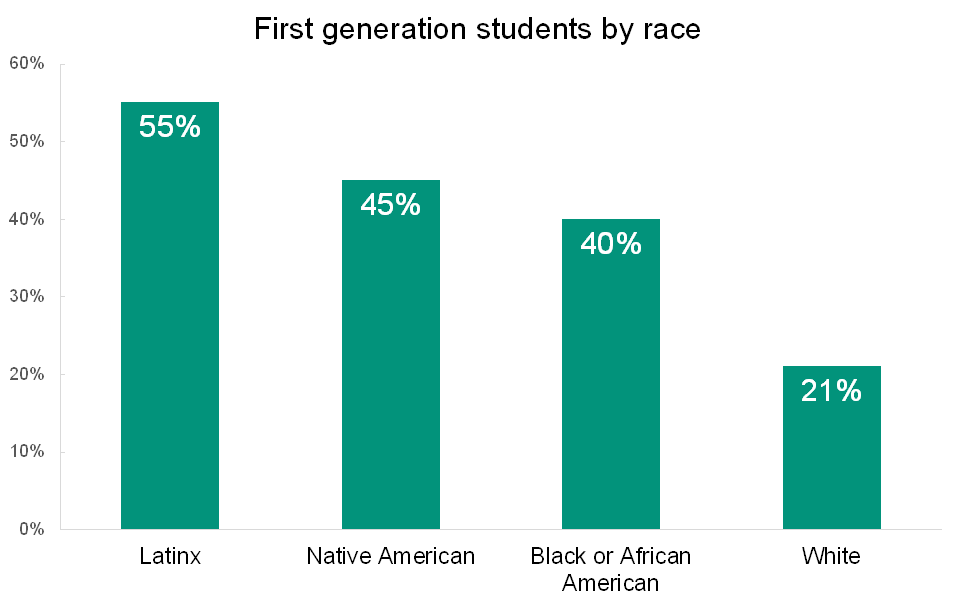

It’s certainly progress that we, as educators and researchers, are recognizing this group of students, but that’s not enough. We need to do more. Especially because there is significant intersectionality between first-generation students and historically underrepresented BIPOC students, including students of color and students from a lower socioeconomic status. According to the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE), 29% of law students are first-generation. Students of color are more likely than their white classmates to be first-generation. More than half of all Latinx students, 45% of Native American students, and 40% of Black or African American students are first-generation.

What Makes First-Generation Students Different?

So why does this matter and why is this group different? Well, first-generation law students often come to law school with fewer resources than their peers, including a lack of social capital. Most importantly, they also come to law school bearing an “achievement gap.” The “achievement gap” refers to the disparity in academic performance – grades, standardized-test scores, dropout rates, college-completion rates, even course selection and long-term success– between groups of students. In this instance, we are referring to the gap between students who have had parents complete some form of higher education (“continuing-generation students”) and those that have not. The Close the Gap Foundation refers to this as “the opportunity gap” instead of the achievement gap, and specifically states that it is “the way that uncontrollable life factors like race, language, economic, and family situations can contribute to lower rates of success in educational achievement, career prospects, and other life aspirations.”[4]

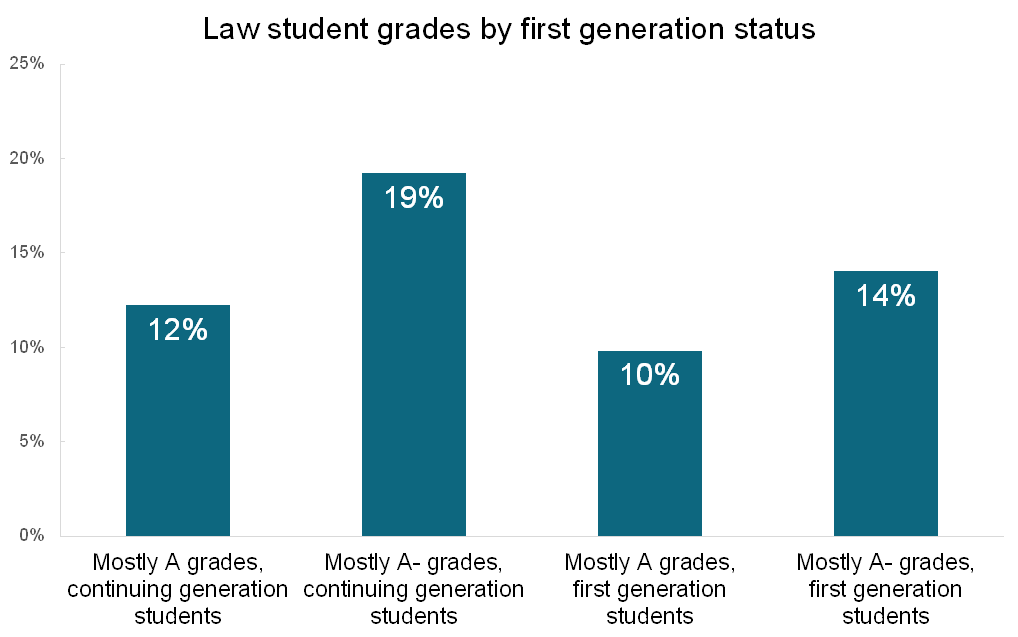

This gap becomes obvious when you look at the data. In the 2021 LSSSE survey, 31% of continuing generation students earned a A- or higher. For first-generation students that number was only 24%. While this might not seem like a staggering gap, without networking and family connections, first-generation students have to rely more heavily on grades for job prospects, so that gap can make a significant difference to their future.[5]

As for social capital, in all professions and cultures there are unwritten rules and norms, generally learned from observing others or knowing people in the culture or profession. Essentially these are not rules you learn about in any explicit way. There is no way for students to study up on these rules, no matter how diligent or well-prepared they are, because they are acquired only through experience. While incoming law students start to pick up on some of these rules during their undergraduate programs, there are still huge gaps where law school and the legal profession are concerned.

Finally, it is far more likely that first-generation students will be providing care for a dependent, either a parent or a child. In fact, 11.3% of first-generation students care for a dependent more than 35 hours per week, as compared to only 5.2% of continuing-generation students.[6] In addition, first-generation students typically end up working more hours, either in legal or non-legal jobs, than their continuing-generation counterparts.

Taken all together, this means that most first-generation students come to law school with considerable hurdles: lower access to finances, lower social capital (i.e., fewer networking connections), lack of exposure to professional norms, and finally, hurdles related to academic preparation, especially when so much of the language used in law school might be brand new to them. And first-generation students themselves know this, coming to law school with concerns surrounding academic success, their career path, building a professional network, finances and family obligations.[7]

What Can We Do?

As legal educators we can do so much. And this starts at the point of admissions. Today, I’m speaking on a panel at LexCon ’22[8] called "Empowering First-Gen Students Through Your Schools' 'Hidden Curriculum,'" along with Morgan Cutright of AccessLex, Teria Thornton, and Susan Landrum, Dean of Students at Illinois College of Law.

Our panel is discussing ways to support first-generation students through the admissions process, navigating financial aid, and finally with academic support once they enter law school. The first step is having these discussions because we often don’t realize the challenges that first-generation students face or what resources they might lack. This is an opportunity for student facing law school professionals – student services, academic support, financial aid, admissions, career services and other administrators – to think through what information we take for granted and then how to make the transition for students a bit easier and more welcoming. For example, even recognizing that many choices they make might be based around financial considerations and scholarships, or staying close to family. Or that purchasing books so that they can read the first class assignment might prove difficult if financial aid checks aren’t distributed before classes begin. Another challenge might be career services assuming that all students have interview appropriate clothes to wear, or can afford such clothes. Some schools have set up interviewing closets where professors and alumni donate old suits for students.

Beyond conversation, at the point of admission, schools can also provide students with a wealth of resources that will help them feel like they belong in law school, and reinforce the message that law school is difficult for all -- not just them. We know that a sense of belonging is linked to positive academic outcomes, such as increased engagement, intent to persist, and achievement[9] However, first-generation students report less belonging, which then increases the achievement gap mentioned above. In addition, students who don’t feel they belong also find it much more difficult to persist in the face of struggle, or even reach out for assistance.

As an example of how we can address a sense of lack of belonging, I used to send incoming students a “law school glossary” upon admissions. It was fairly simple, only a few pages of common words that we tend to use. This was sent to all students, not just first-gen, because some of the terms we use on a daily basis are mystifying to anyone who is new to the study of law. For example, what is a “1L” or what on earth is “K” or “Civ pro”? Abbreviations and acronyms can be just as daunting, and alienating, as the Latin often used.

Because first-generation students often assume that everyone else knows things that they don’t, they might hesitate to ask what are perfectly reasonable questions. Providing them with a quick list of frequently used terms is a great way to decrease feelings of uncertainty. This glossary turned into a book – The First Generation’s Guide to Law School[10] – which was essentially the memo I wish I had received before I started law school. I couldn’t cover everything, but tried to cover most of the unwritten rules surrounding law school, as well as the core academic skills needed to thrive. I wanted to make sure that students could go into their first week of classes feeling confident.

In addition, there are many summer bridge programs that exist. I’m currently working on such a program for the Law School Admission Council (LSAC), and it will be available in the summer of 2023. We had a small bridge program in 2022, Law School Unmasked, and received positive feedback from students on how it increased their feelings of confidence and belonging, and generally increased their ability to succeed in their first semester.[11] For example, “It was very helpful for me as a first generation college and now law student since I do not have anyone I can turn to for help with these topics we went over. Figuring out how things work as a first generation student constantly seems like an uphill battle of asking lots of questions to lots of people who always seem to have vastly different answers and then finding out which answers are correct. This program helped to answer a lot of questions that would have made me feel lost for the first semester of law school.” This shows that programs designed for first-generation students can and do make a difference!

Finally, I encourage all schools to support the formation of a first-generation law student group. This can help ensure first-gen students feel connected, and in a very obvious way, realize they aren’t alone. When I was in law school, I assumed that I might be the only person in the building who didn’t have parents who went to college. However, when I started writing my book – and asking for stories and advice – I discovered that many of my friends and professors were, in fact, also first-generation students. This was shocking to me. So a student group, first and foremost, signals to students that they aren’t the only ones. LSAC is currently working on a National First-Generation Law Student Group, and meeting with already existing student groups to find the best ways to support and foster these types of student organizations.

If you have questions about how to support first-generation students, please feel free to reach out to me at mhale@lsac.org.

[1] Cite 3

[2] FAQ: First-Gen Definition, The Center for First-generation Success, https://firstgen.naspa.org/why-first-gen/students/are-you-a-first-generation-student.

[3] Way back in the dark ages in 2003.

[4] Close the Gap Foundation, last visited May 18th, 2022 https://www.closethegapfoundation.org/glossary/opportunity-gap?gclid=Cj0KCQjwspKUBhCvARIsAB2IYuscRgwXvBQgnHlxQtXJ34Bw4m8g4X_HdMdS_csWATPxgPN0dzuk6eUaAuwKEALw_wcB

[5] id.

[6] Law School Survey on Student Engagement, LSSSE Survey Tool 2021, https://lssse.indiana.edu/about-lssse-surveys/ 1 (Last visited Jan. 17, 2022).

[7] Id.

[8] https://web.cvent.com/event/e2323c1d-5bfb-4ab2-aad0-3cc606276ab1/summary

[9] Id.

[10] https://cali.org/books/first-generations-guide-law-school

[11] https://www.lsac.org/law-school-unmasked

A Critical Tool for Dean and Faculty Leaders

A Critical Tool for Dean and Faculty Leaders

Austen L. Parrish

Dean and Chancellor’s Professor of Law

University of California, Irvine School of Law

The job of a law school dean has changed. If once to be “successful... you need[ed] to be a distinguished scholar,” now the day-to-day responsibilities of a law dean are much more varied and complex. Just recently, a piece in Bloomberg Law explained that if the “[l]aw school dean once was a dream job . . . [t]hese days, the position is more like being chief executive of a sprawling business than a tweed-clad dispenser of constitutional wisdom.” A landmark Association of American Law School’s study on the American Law School Dean underscored that during the pandemic deans spent considerable time on crisis management, on issues related to diversity, equity, inclusion, and on topics of student life and student conduct. The pressures of continued intense hyper competition—whether that’s recruiting and retaining talented students, faculty, and staff; the complexity and demands of core operations, including admissions, career services, communications, finance, student services, among others; and the need to enhance the school’s research, teaching, and service missions, while navigating complex university labyrinths—in many ways reflects that higher education itself operates in a much more complex context than it once did.

As the role of the dean has become broader and more complex, the need for quality data upon which to track progress and base decisions has become more important. In the last decade, the resources available to law deans have expanded dramatically. AccessLex Institute’s Analytix, which aggregates ABA data about legal education, its research and data portal, and its annual legal education data deck are some of the best and most useful examples. The AALS compendium of data resources, the Law School Admission Council’s data on admissions and student recruitment, and the National Association of Law Placement’s research and statistics are others. In my own experience, when it comes to gauging student engagement and the student experience, few resources are more useful than the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE).

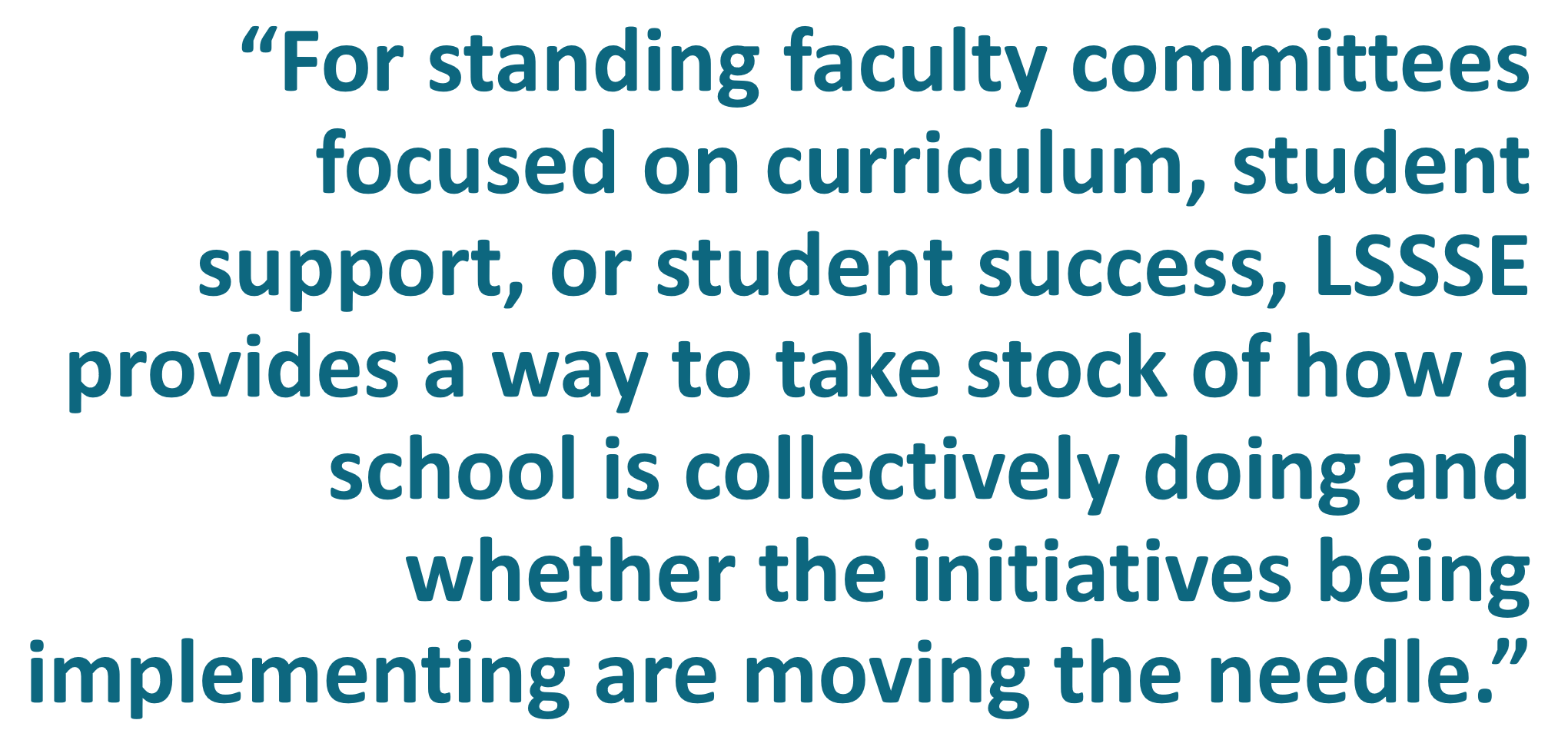

LSSSE helps with data-driven decision-making. Schools that have consistently taken advantage of LSSSE now have a wealth of longitudinal information from over 17 years of surveys. I’ve found, however, that the survey also has a more straightforward function. If we care about our students and their experiences, why wouldn’t we want to track and measure student perceptions of that experience? And tracking those perceptions over time provides some indication of whether we’re making progress on our goals. Comparisons with other institutions are useful in creating benchmarks too. For standing faculty committees focused on curriculum, student support, or student success, LSSSE provides a way to take stock of how a school is collectively doing and whether the initiatives being implementing are moving the needle.

LSSSE helps with data-driven decision-making. Schools that have consistently taken advantage of LSSSE now have a wealth of longitudinal information from over 17 years of surveys. I’ve found, however, that the survey also has a more straightforward function. If we care about our students and their experiences, why wouldn’t we want to track and measure student perceptions of that experience? And tracking those perceptions over time provides some indication of whether we’re making progress on our goals. Comparisons with other institutions are useful in creating benchmarks too. For standing faculty committees focused on curriculum, student support, or student success, LSSSE provides a way to take stock of how a school is collectively doing and whether the initiatives being implementing are moving the needle.

Personally, I have found it’s the bread-and-butter questions of the survey that are most helpful. How satisfied are our students in the career counseling, personal counseling, academic advising, financial aid counseling, as well as library and technology assistance they receive? How often and in what ways do our students interact with faculty? The responses don’t tell you as a dean or a faculty committee what to do, and the questions measure perceptions as much as anything, but the survey responses provide important insight into the extent our students are feeling supported, and whether we’re building the inclusive, rigorous academic community we want. And on a year-to-year basis, the survey provides red flags and early warning signals if there’s a sudden drop in an area. It also provides reasons for celebration and congratulations to staff over sustained improvement. Of course, if you care about fundraising, questions asking students to evaluate their overall law school experience, and whether if they could start over they would attend the same law school, are critical. And for being a dean in California, where the bar exam is notoriously exclusionary, the new AccessLex and LSSSE partnership that seeks to explore the connections between student engagement and bar performance is a welcome development.

I’ve found LSSSE useful in other ways too. For one, LSSSE’s special reports have been insightful on providing a perspective on issues that I care about, and that I know many of my dean colleagues care about too. The 2020 Annual Report, Diversity & Exclusion, or the special report on The Changing Landscape of Legal Education, which provides a 15-year retrospective, both come to mind. More pragmatically, as the ABA Section on Legal Education has required that schools track and assess outcomes, LSSSE and its Accreditation Report and Accreditation Toolkit provide near essential tools in demonstrating compliance with accreditation requirements. I’m puzzled how some schools—unless they are doing extensive annual surveying in a different form—are easily able to show compliance with all the new standards without using LSSSE.

I’ve found LSSSE useful in other ways too. For one, LSSSE’s special reports have been insightful on providing a perspective on issues that I care about, and that I know many of my dean colleagues care about too. The 2020 Annual Report, Diversity & Exclusion, or the special report on The Changing Landscape of Legal Education, which provides a 15-year retrospective, both come to mind. More pragmatically, as the ABA Section on Legal Education has required that schools track and assess outcomes, LSSSE and its Accreditation Report and Accreditation Toolkit provide near essential tools in demonstrating compliance with accreditation requirements. I’m puzzled how some schools—unless they are doing extensive annual surveying in a different form—are easily able to show compliance with all the new standards without using LSSSE.

LSSSE has been useful for another reason. LSSSE now houses the largest repository of law student data in the U.S. with over 400,000 responses over seventeen years. That’s a powerful tool for researchers, but it’s also just helpful for deans to do their jobs. It’s not enough for a law dean to know what’s happening in their own school. Alumni, provosts, presidents, and other stakeholders want to know trends in legal education. Having a broader, empirical view of the changes of legal education is useful to rebut persistent misinformation and caricatures about legal education.

LSSSE has shown how legal education has changed in the last seventeen years. The surveys show that there’s room for innovation and improvement and that rising student debt remains a concern. Yet on balance the surveys tell a positive story of school success. Overall levels of satisfaction remain high, and schools have made progress in improving the quality of legal education and the commitment to student support. While variation between law schools can be significant, the surveys reveal an American legal education system that is increasingly diverse, has strong student services with engaged full-time teachers and scholars, and underscores that schools overall have strengthened their commitment to supporting students in their path to launching satisfying careers (with academic, career, and personal advising).

LSSSE is a valuable tool for deans. One that I’ve used consistently over the last decade, and one I will continue to use.

Guest Post: What’s Actually At Stake in the SCOTUS Challenge to Race-Conscious Admissions

Shirley Lin, Assistant Professor of Law

Brooklyn Law School

Clara Williams ‘23

Brooklyn Law School

Consider the following hypothetical law school candidate. She is a child of limited-English-proficient immigrants, growing up in a majority-minority neighborhood of Queens, New York. Her community and adjoining zipcodes had been deprived of public investment for decades. She and her siblings were the first in their household to graduate high school, then college. Because of their race and ethnicity, they experienced harassment from a young age and, one of them, a violent beating in high school. By the time she applied to law school, she took her first course in standardized testing just before her second and final attempt on the LSAT. Co-author Professor Lin’s experience with affirmative action in higher education would have been markedly different if the Supreme Court decides to overturn four decades of precedent allowing schools’ admissions programs to consider race along with other factors.

After decades of being held up as a racial foil against other communities of color in racial politics—especially in debates over affirmative action—Asian American communities are wary of being used as pawns to undo efforts to address racial inequality. After withstanding repeated challenges to affirmative action, in 2003, the Court reaffirmed the current doctrine that admissions programs may consider race among other factors that contribute to campus diversity in Grutter v. Bollinger. In tandem appeals against Harvard and University of North Carolina, petitioner Students for Fair Admissions (or SFFA, led by a white affirmative action opponent, Edward Blum), now seeks to do so again in a bid to undo the practice of race-conscious admissions entirely.

Statistics are central to SFFA’s challenge on several levels: in evaluating how interested parties have positioned racial categories; in illustrating what is at stake; and in contextualizing the relevance of these appeals to legal education. In fact, for nearly a decade, the majority of Asian American voters have supported affirmative action—today, at nearly 70 percent. This includes the 6,000-member Harvard Asian American Alumni Alliance (H4A, representing all of Harvard’s Schools), which joined amici student and alumni groups supporting Harvard’s ability to consider race in its admissions process. H4A has underscored that a racially diverse student body creates the best educational environment for everyone—including Asian Americans.

Emphasizing a consistent line of studies demonstrating that racial diversity increases tolerance and empathy across racial lines, the Asian American Legal Defense & Education Fund filed an amicus brief last month in support of the respondent universities, on behalf of 121 AAPI scholars and community group signatories (including Professor Lin). Amici highlighted the meteoritic rise in anti-Asian American hate crimes, in particular extremely violent attacks and murders, that persist, in emphasizing the continuing relevance of the benefits of racial diversity that Grutter recognized two decades ago.

Numbering at least 24 million, Asian American communities are kaleidoscopically diverse even in terms of ethnicity and class stratification alone. Asian Americans have undergone profound changes in the last two decades. Their cultural and political experiences nationwide defy pat generalizations about race, phenotype, immigration status, religion, and experiences with language barriers. For example, 12 of 19 subgroups by Asian origin analyzed by the Pew Center currently experience poverty at rates as high as—or above—the level for overall U.S. population. Today, roughly 6 in 10 U.S.-born Asian Americans are members of GenZ (i.e., aged 22 or younger), and another 25% of the population considered Millennials. Their experiences in schools (including legal education) defy the racial stereotypes of Asian Americans that formed a generation or two ago as the “model minority” who can simply, meritocratically, join the middle- or upper-middle-class.

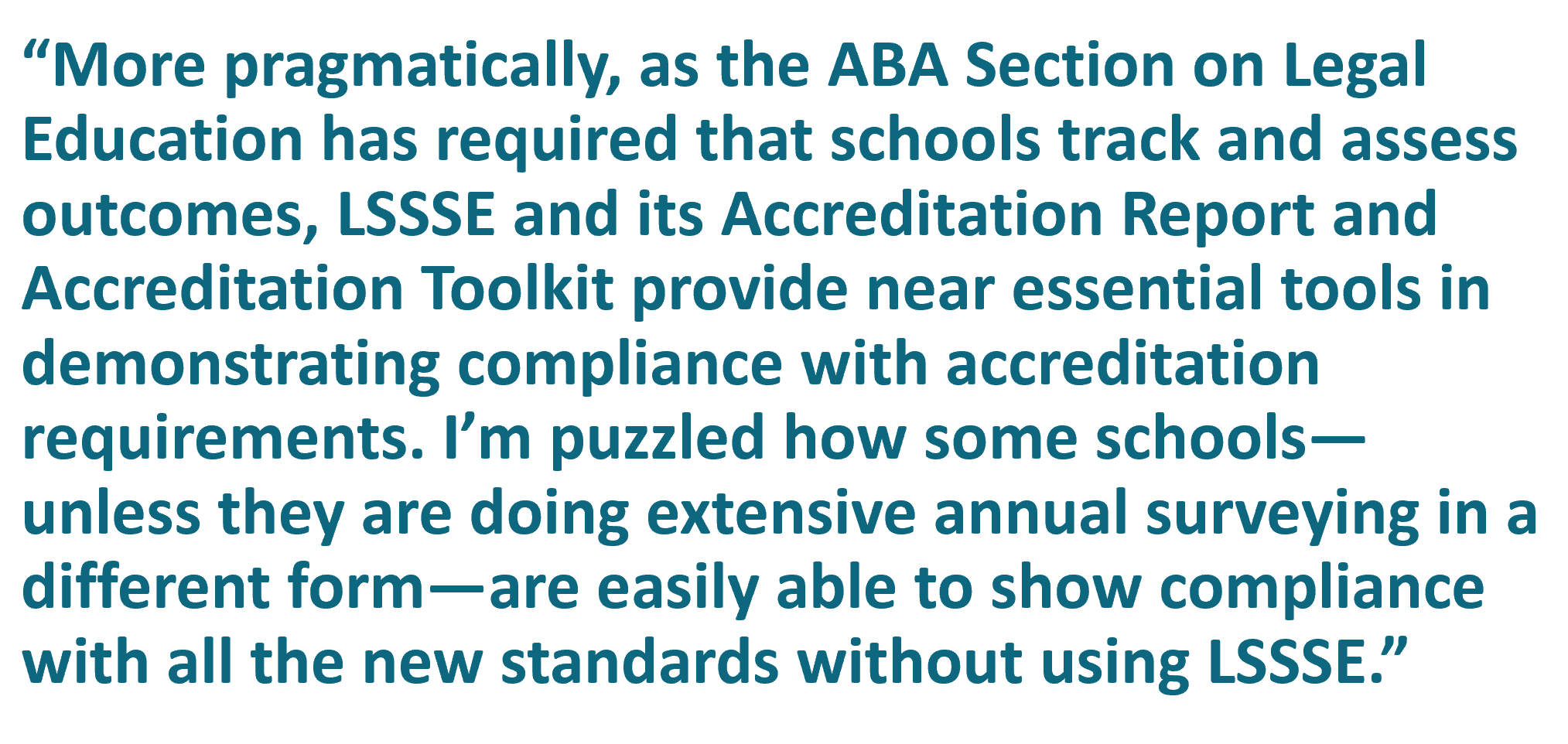

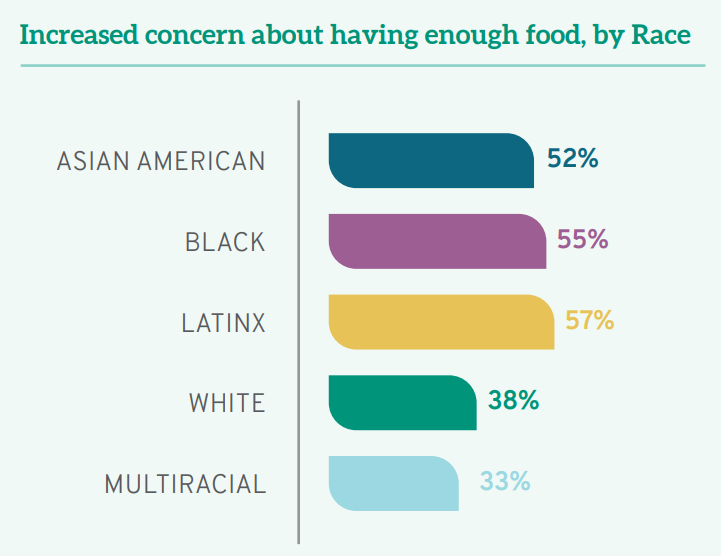

Recent reports from the Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) provide a far more accurate picture than the briefs provide. For example, during the ongoing COVID crisis, concerns about access to adequate food and housing among Asian American law students were on par with Black and LatinX law students:

LSSSE, The COVID Crisis in Legal Education (2021)

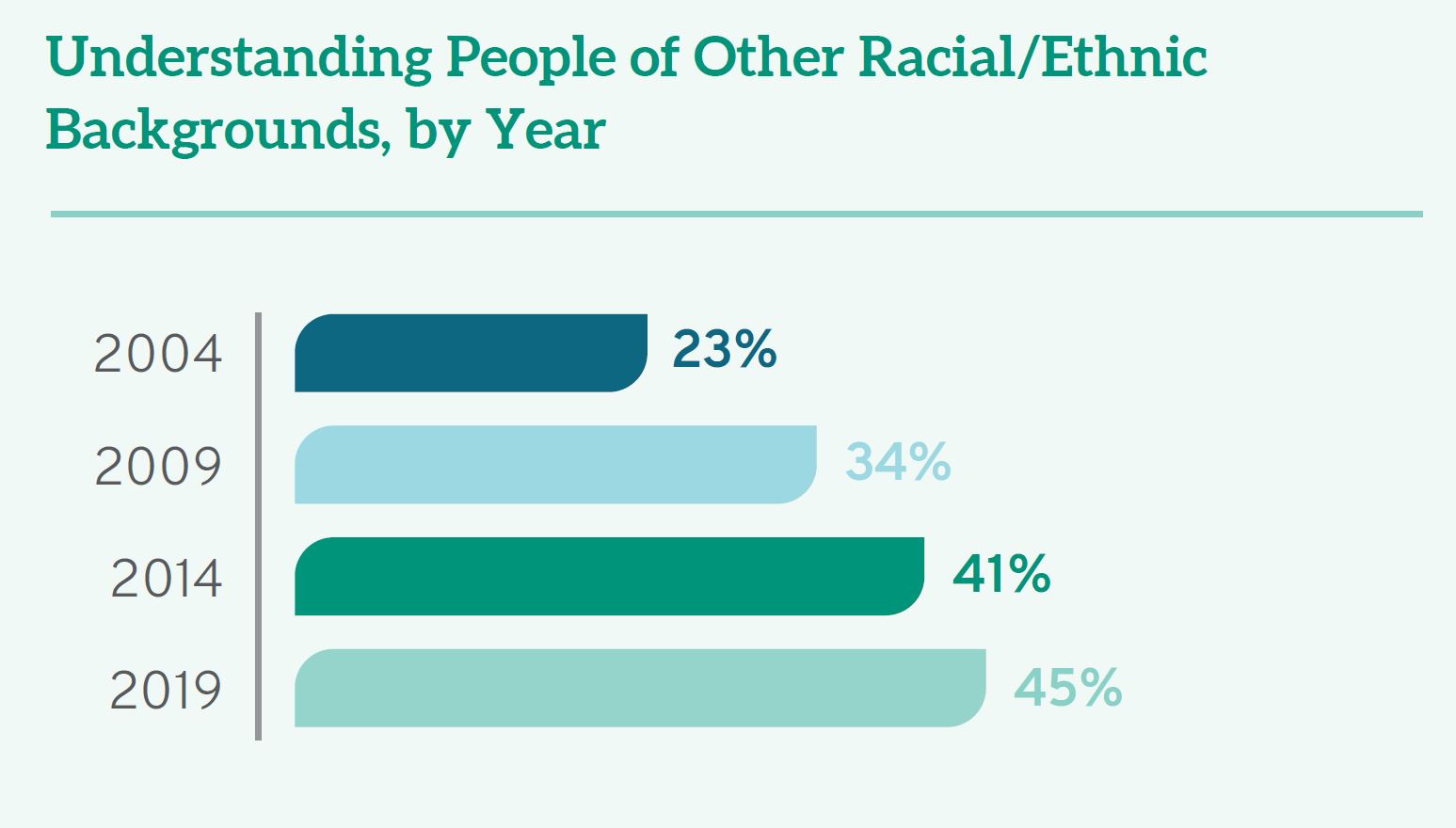

Meanwhile, LSSSE’s 2020 report providing a 15-Year Retrospective reflects that, in the intervening time since Grutter and its subsequent increase in student racial diversity, students were twice as likely to report that their law school contributed to their understanding people of other racial or ethnic backgrounds— progressing from a paltry 23% to 45%:

These students’ experiences, of course, predate the ABA’s modest revision earlier this year of law school Accreditation Standard 303(c), which now states: “[a] law school shall provide education to law students on bias, cross-cultural competency, and racism: (1) at the start of the program of legal education, and (2) at least once again before graduation.”

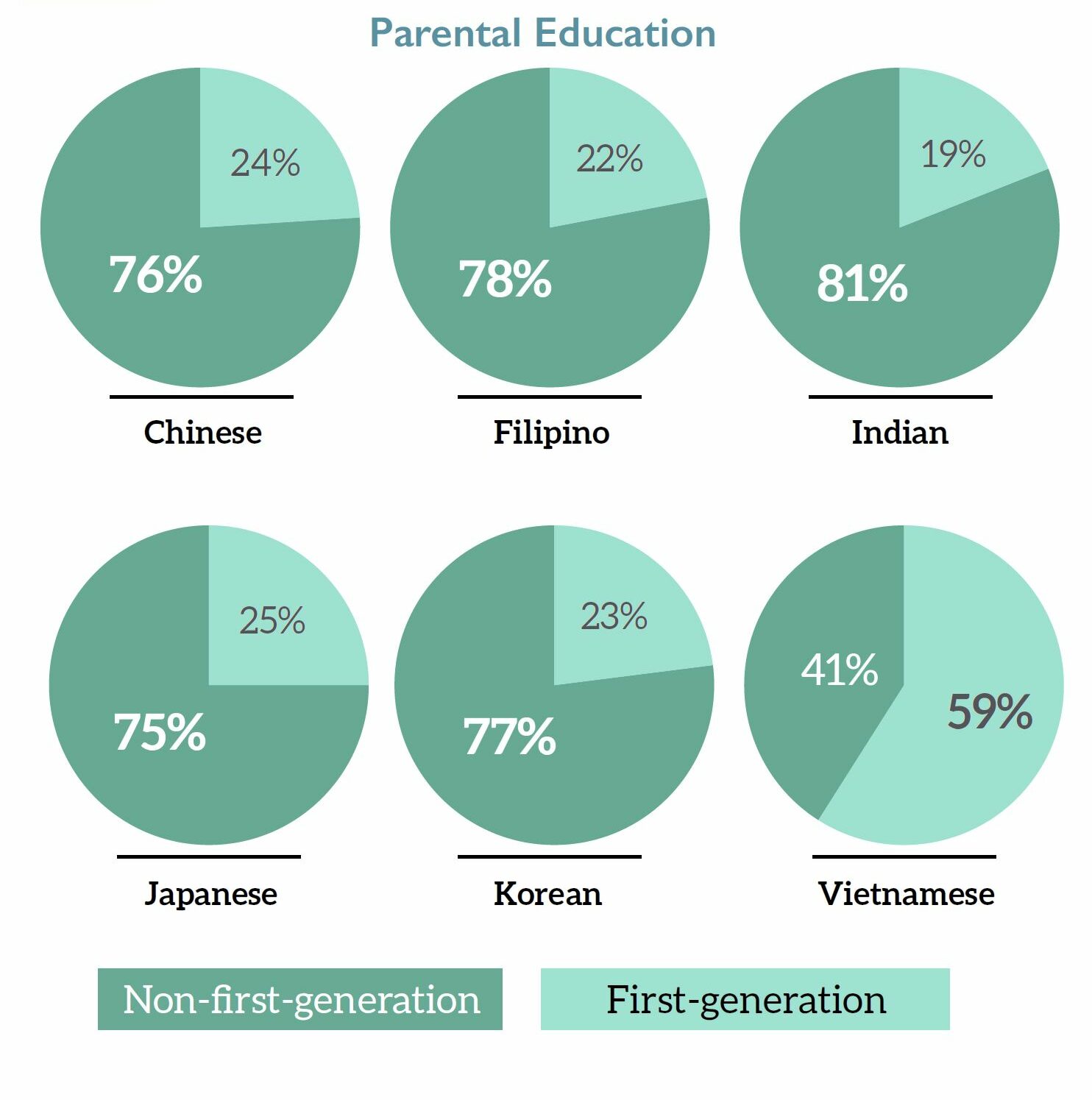

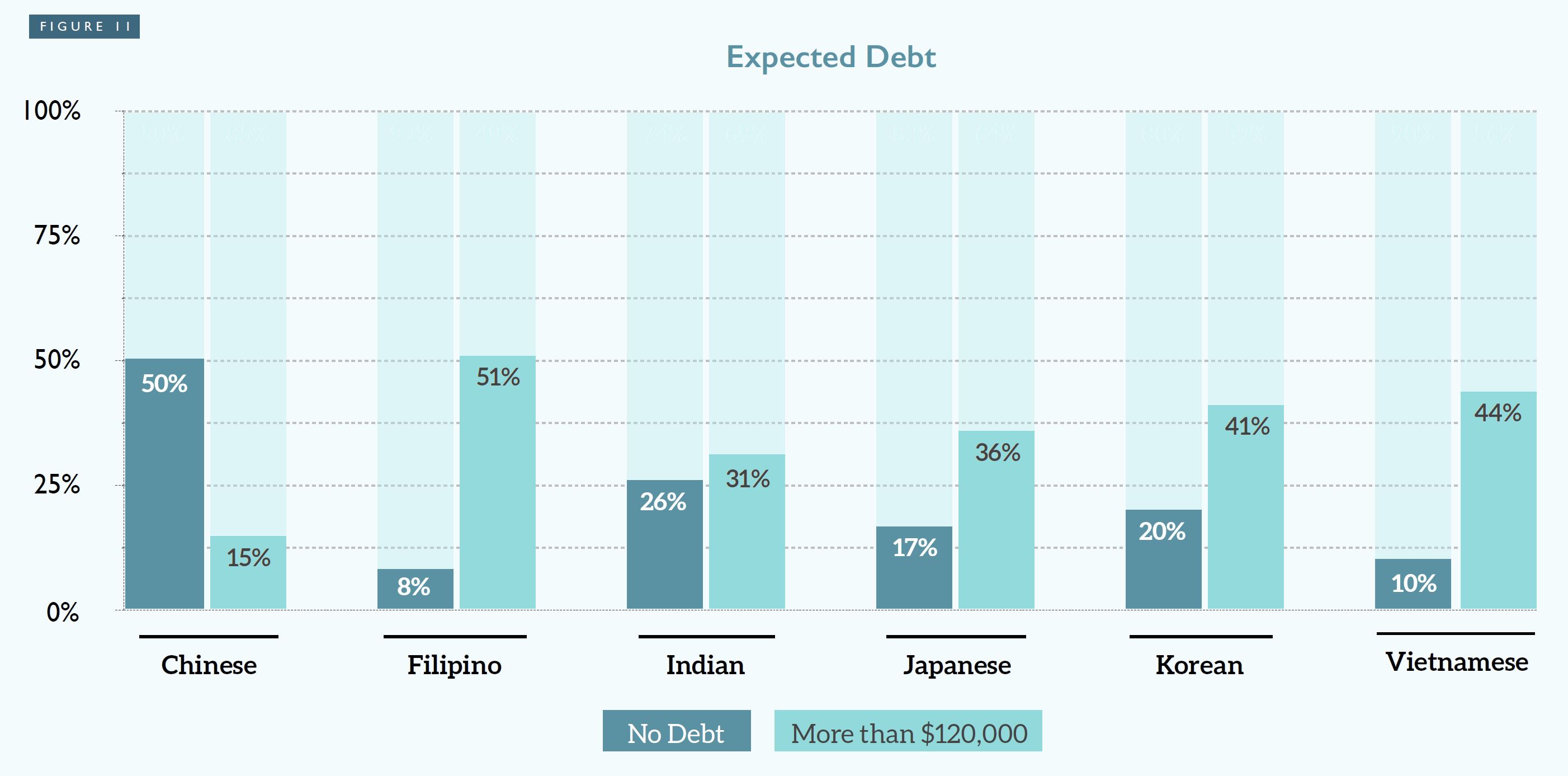

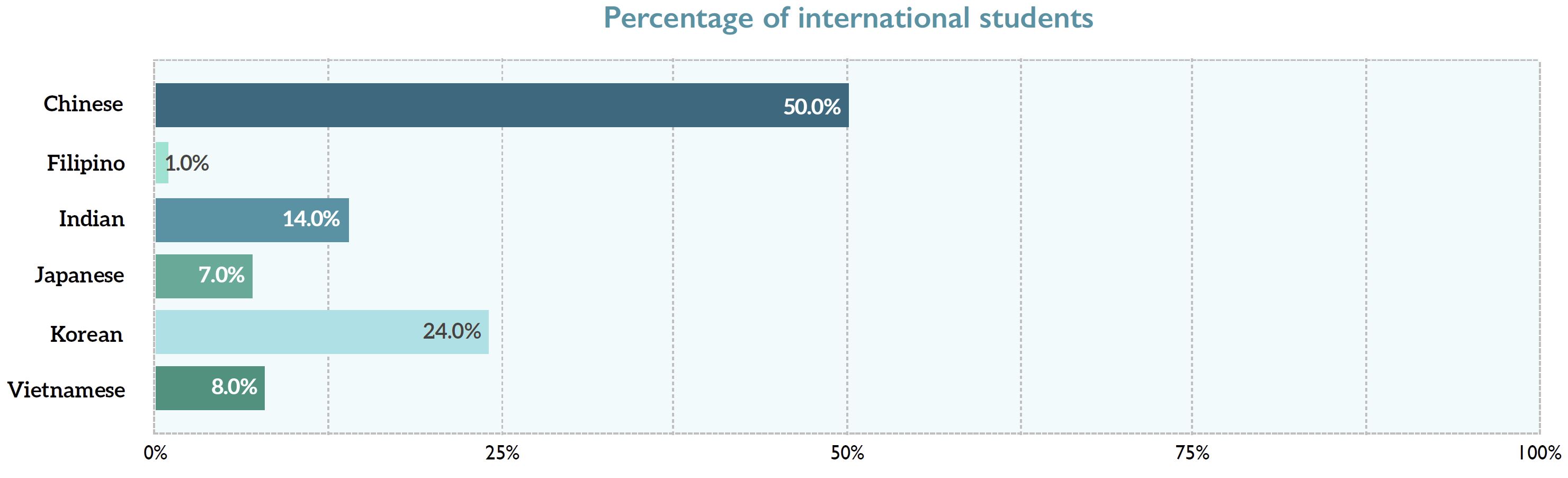

Taking time to drill down into the experiences of subgroups within Asian American communities yields a wealth of information about the similarities and, perhaps just as crucially, the divergent experiences of such a vast grouping. For instance, Vietnamese American students are half as likely as Indian American students to have parents who received a college education. Chinese students comprise 50% of the international students, who are generally not eligible for merit-based scholarships.

Diversity Within Diversity (2017)

Most troubling is that, in its Harvard litigation, SFFA claims to be concerned with assisting AAPI applicants against “negative action” by proposing as an alternative affirmative action based solely on income. Yet the group avoids acknowledging that such plans ultimately provide the greatest boost to white applicants—not racial minority applicants—because they do not account for additional systemic hurdles racial minorities from impoverished families face. Meanwhile, a ruling that would prohibit the use of race while leaving in place “colorblind” practices that unfairly benefit wealthy white applicants belies SFFA’s professed concern for Asian American applicants.

Rather than confounding admission programs, our current doctrine on race-conscious affirmative action does not prohibit law schools or colleges from assessing the multiple dimensions of advantage and disadvantage as they intersect with race (including for white applicants). To the contrary, it expects schools to assess individual applicants holistically. Students of color—including Asian American students—overcome barriers to the profession compounded by race alongside class, disability, gender, and other dimensions of inequality. Professor Lin’s first-hand experience with the inequities her family and neighbors faced remained central to her pursuit of legal advocacy, and now research and teaching, which investigate how law binds racial and economic injustice. Her unlikely route to academia would scarcely have been possible without the nuanced, race-conscious approaches intact in current doctrine.

Nonetheless, conservative proponents of “colorblindness” will soon ask the Justices to discard nearly 50 years of settled law on race-conscious admissions programs in higher education. At a time when debates over K-12 curricula foreground ideological attempts to silence all conversation about the ways in which race fosters systemic and institutional inequality, SFFA’s blunderbuss legal challenge has—at a minimum—reinvigorated examination of actual racial diversity so that legal academia, too, must take note.

Guest Post: Using Meaningful Admissions Data to Improve Legal Education and the Profession

Anahid Gharakhanian

Vice Dean & Director of the Externship Program

Professor of Legal Analysis, Writing, and Skills

Southwestern Law School

Natalie Rodriguez

Associate Dean for Academic Innovation and Administration

Associate Professor of Law for Academic Success and Bar Preparation

Southwestern Law School

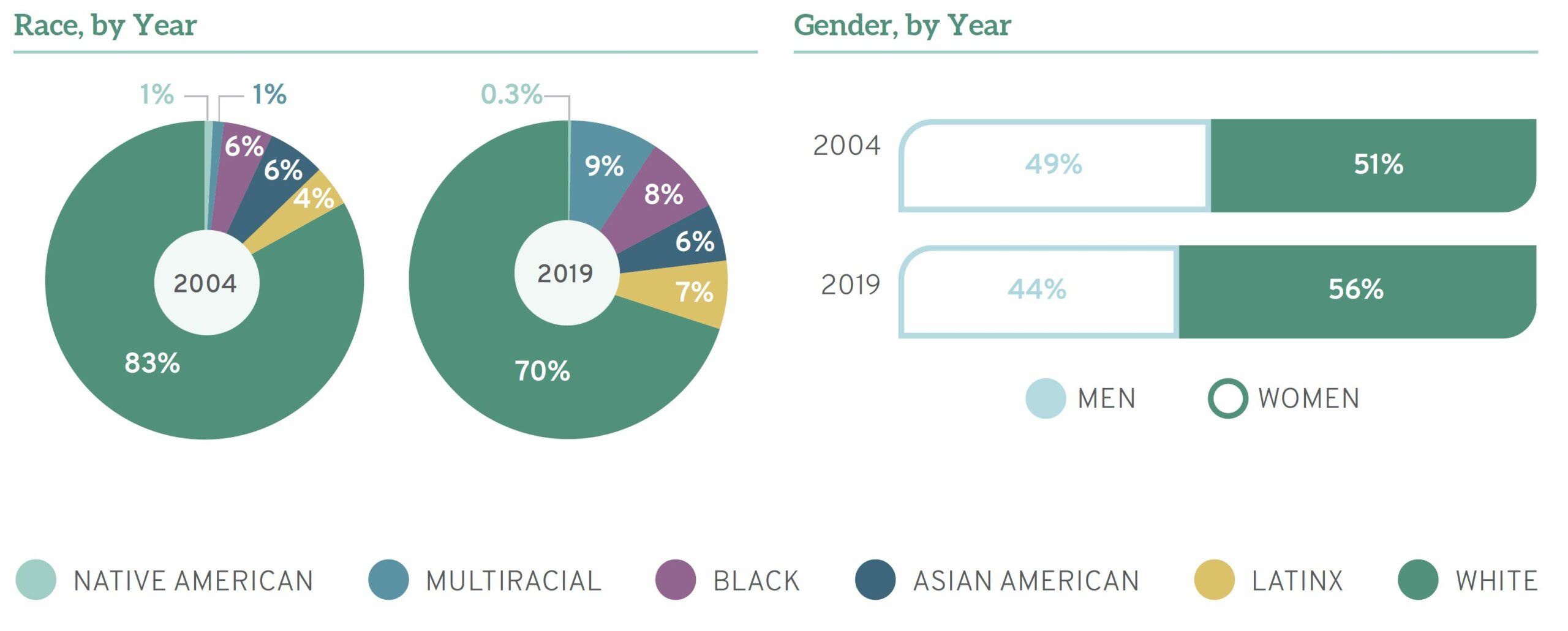

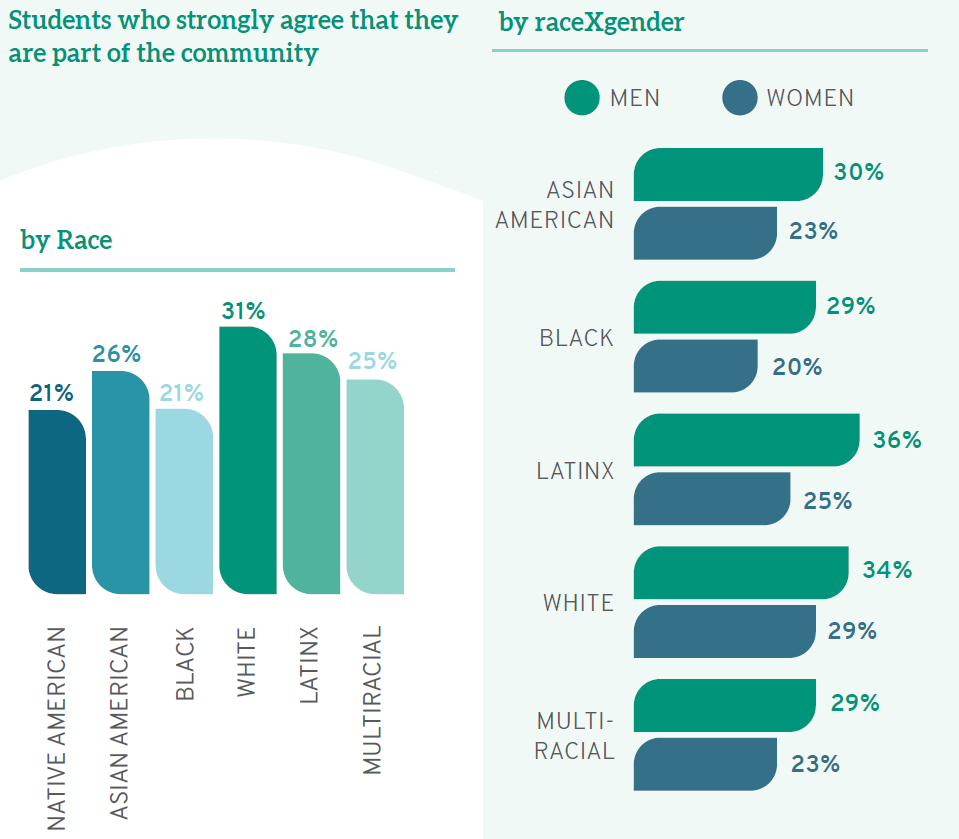

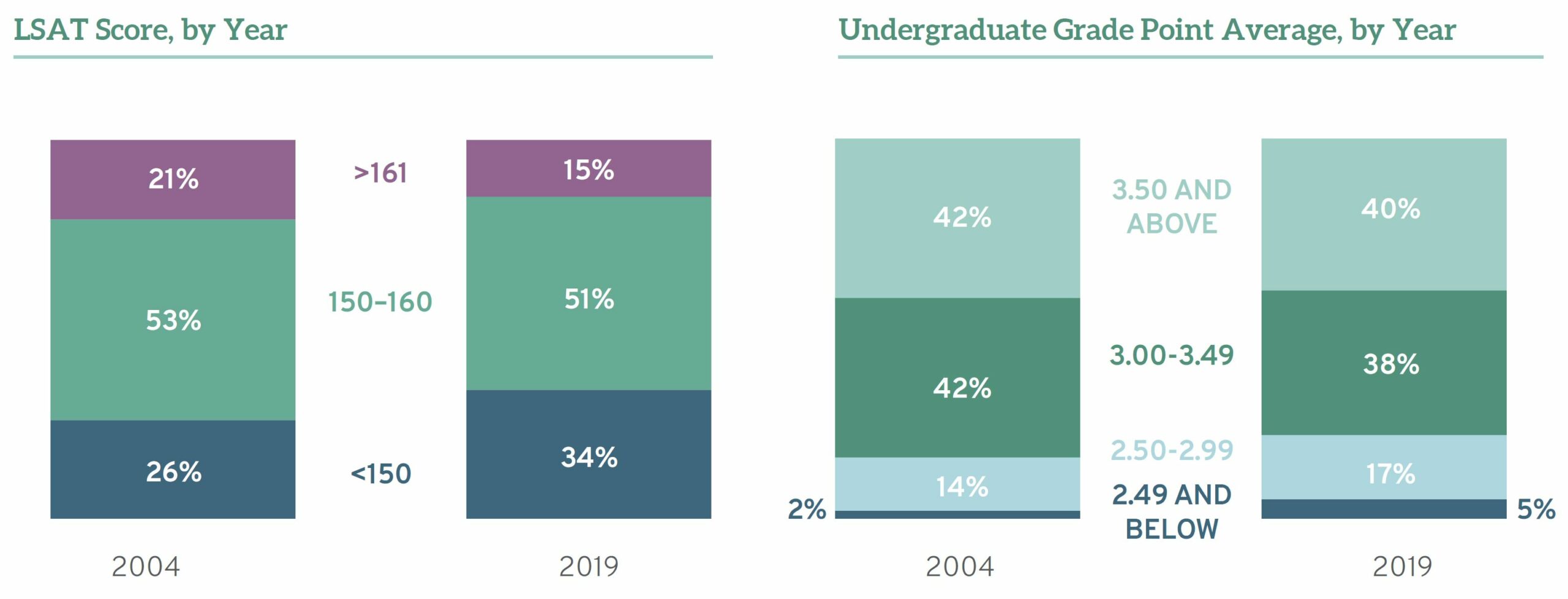

Conversation about increasing diversity and doing better when it comes to inclusion and belonging is everywhere in legal education. What’s critical though is empirically tracking how well we’re actually doing. The Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) provides invaluable and sobering data that should serve as a beacon to legal educators’ aspirational goals of cultivating diversity, inclusion, and belonging in their schools and in the profession. LSSSE’s 15-Year Retrospective – The Changing Landscape of Legal Education – tells us that there’s a positive trajectory with minority enrollments from 2004 to 2019.

But the jarring news is that minority students’ sense of belonging – especially women of color students– is quite a bit lower than that of White students. As LSSSE’s 2020 Diversity and Exclusion Report points out, “Scholarly research indicates that students who have a strong sense of belonging at their schools are more likely to succeed.”

The data unequivocally tells us that we need to do a lot better for ALL law students to succeed. But the effort should start much earlier than when law students start law school. We need rigorous rethinking and innovation in law school admission practices – whereas to date the hyper-focus is on the limited numerical indicators of undergraduate GPA and especially LSAT score.

For the past three years, Southwestern Law School has innovated with such a first-of-its kind approach to admissions practices. The research project and initial results are detailed in “More than the Numbers”: Empirical Evidence of an Innovative Approach to Admission, Minnesota Law Review (Vol. 107, forthcoming), co-authored by the co-authors of this blog and Dr. Elizabeth Anderson, and will be presented at the Minnesota Law Review Symposium, on October 7, 2022, “Leaving Langdell Behind: Reimagining Legal Education for a New Era.” Interestingly, Southwestern’s empirically-based novel approach seems to have provided a notable boost to the matriculants’ sense of confidence or belonging in attending law school. More on that in a bit.

Southwestern’s project is driven by the moral imperative that law schools – as gatekeepers to the legal profession – should commit to innovative and rigorous admissions processes that define merit broadly and provide opportunities based on a spectrum of factors, beyond the traditional numerical indicators. In furtherance of this commitment, several years ago, Southwestern developed an evidence-based tool to more fully and meaningfully assess applicants’ law school potential. This tool goes beyond the limited cognitive measure of the LSAT, which many criticize as an impediment to diversifying law schools and the profession and which at best is only modestly predictive of first year law school performance.

Southwestern’s approach focuses on that group of applicants whose application materials show promise but also raise questions about the applicant’s current readiness for law school. These applicants are invited to participate in a methodical waitlist interview process where they are asked a series of questions based on several factors identified in the IAALS’s Foundation for Practice (“Foundations”) study as necessary for first-year attorneys. Three years into this project and based on hundreds of admission interviews working with Dr. Elizabeth Anderson we have analyzed our approach. The data has produced initial reliability and validity metrics for the measure developed – i.e., a tool that could be used with confidence in the admissions process.

Southwestern’s approach has included three steps. First, Southwestern identified what needs to be measured – i.e., certain foundations necessary for first-year practice as established by the Foundations study and hence assumed to be necessary to law school success. Second, the school identified why these factors need to be measured – i.e., to provide access to legal education with measures that matter. Third, the school designed the empirical research to support the development of a reliable and valid measure of this construct. Relatedly, Southwestern developed a measure of “nontraditional readiness for law school” using a design that focused on a psychometric research design, where psychometrics is the research practice of formal development of reliable and valid measures/assessments. Southwestern has found that the developed tool/measure is measuring what it set out to measure. This tool/measure will produce a score that will then be used in predictive validity analyses, as well as predictive modeling of law school success outcomes.

Interestingly, and beyond the quantitative data, based on comments shared by the interview matriculants, for purposes of adding context to the paper we’ve written about the admissions project, we’ve learned that the interview experience provided a notable boost to their confidence in attending law school. This was not an outcome that Southwestern had hypothesized or planned for but was a palpable part of the comments shared by the matriculants. Seeing the LSSSE data about belonging, it’s imperative that we create a sense of belonging starting with the admissions process.

The matriculant’s comments are indelible. A third-year interview matriculant noted:

I was very nervous when I came to the school for the waitlist interview. But afterward I felt heard and this motivated me. It gave me confidence, and I felt I couldn’t let the school down and I now had the opportunity to follow my purpose.

A second-year interview matriculant noted:

With the waitlist interview, Southwestern made the admissions process more personal and it showed me that the administration really values the lived experience of potential students and wants to hear what I have to say. This gave me confidence about law school and what I can contribute/accomplish.

And a first-year interview matriculant noted:

My waitlist interviewer dug deep and tried to understand me. She heard me, which was incredible. I knew law schools aren’t comfortable taking a chance but I was hoping some schools would want to hear my story and that’s what the waitlist interview did for me. This gave me the chance and confidence to pursue the dream that started with watching Fresh Prince of Bel-Air when I was a kid and thinking it’s so incredible to see Black attorneys and I want to be an attorney.

Our work has been well-received. We recognize, however, there is work left to be done and LSSSE is uniquely positioned to contribute in this area and help drive the necessary change through additional data. As part of its annual survey, LSSSE could include questions designed to gather data on law students’ admissions experiences. As our approach to admissions shows, establishing a sense of belonging can begin well before orientation. This unintended yet profound outcome is worth additional exploration. As indicated in the 2020 Diversity and Exclusion Report, a strong sense of belonging can make the difference in whether a student feels they have the support they need to thrive, especially women of color.

Further, as part of its longitudinal studies, LSSSE could also consider ways to track admissions factors beyond the limited indicators of LSAT and UGPA. The 2020 15-Year Retrospective – The Changing Landscape of Legal Education points out overall drops in UPGAs and LSAT scores.

This is helpful information, but the continued hyper-focus on these traditional factors, and not probing into and tracking other admissions-related data, contributes to perpetuation of limiting entry into law school and the profession based on narrow concepts of merit and potential.

These are just a few ideas. But to be sure, empirical inquiry and evidence must lead the way to change in admission practices. With its dedication in working for the betterment of legal education and its rigor in research practices, LSSSE certainly has a critical role to play in encouraging innovative law school admissions practices that more fully and meaningfully assess merit and potential while creating an inclusive and engaging pre-matriculation experience.

Dispelling the Asian American Monolith Myth in U.S. Law Schools

Dispelling the Asian American Monolith Myth in U.S. Law Schools

Katrina Lee

Clinical Professor of Law, and Director of Program on Dispute Resolution

The Ohio State University, Moritz College of Law

Rosa Kim

Professor of Legal Writing

Suffolk University Law School

In the past year, following an exponential rise in anti-Asian violence and discrimination in the U.S., we wrote an essay about inclusion of Asian American faculty in legal academia. We discussed harmful stereotypes and myths about Asian Americans. We called on the legal academy to do more to acknowledge and address the challenges faced by Asian American faculty and to amplify their voices, work, and presence.

Law schools must also do the same for Asian American students in U.S. law schools.

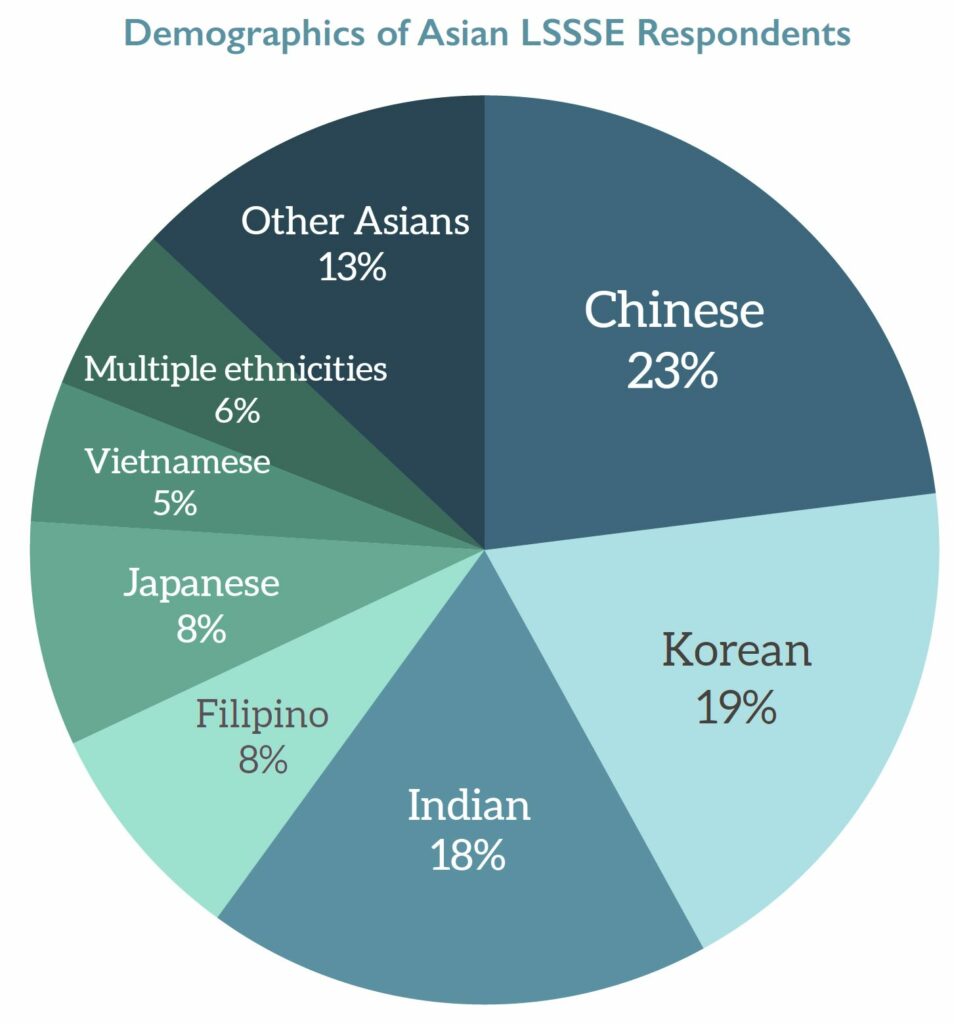

Asian Americans have often been viewed and treated as a single homogenous group. And yet the story of Asians in America is one of rich diversity. Today more than 20 million people who identify as Asian American live in the U.S.[1] The term Asian American encompasses at least 21 distinct groups.[2] In 2019, people who identify as Chinese, Indian, Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese accounted for 85% of Asian Americans.[3]

Asian Americans are diverse economically. The disparities in income across Asian American households are among the widest in the country. While Asian American households in the U.S. had a median annual income of $85,800 in 2019—higher than the $61,800 among all U.S. households—most groups of Asian Americans report household incomes well below the national median for Asian Americans.[4] For instance, Burmese American households have a median income of $44,400.[5]

Unsurprisingly, Asian American law students[6] are diverse. LSSSE survey data about Asian American students dispels the monolith myth and reveals the need for law schools to act to provide support for all Asian American students. LSSSE’s recent report of Asian American law students is aptly named Diversity within Diversity: The Varied Experiences of Asian and Asian American Law Students.

Within the group of Asian American law students surveyed, 81% of respondents comprised six ethnic groups: Chinese, Korean, Indian, Filipino, Japanese, and Vietnamese.

International students of Asian descent are a growing cohort in U.S. law schools. By far, Chinese respondents were more likely than any other group to be international students; 50% percent of them identified as international students, while just 1% of Filipino respondents identified as international students.

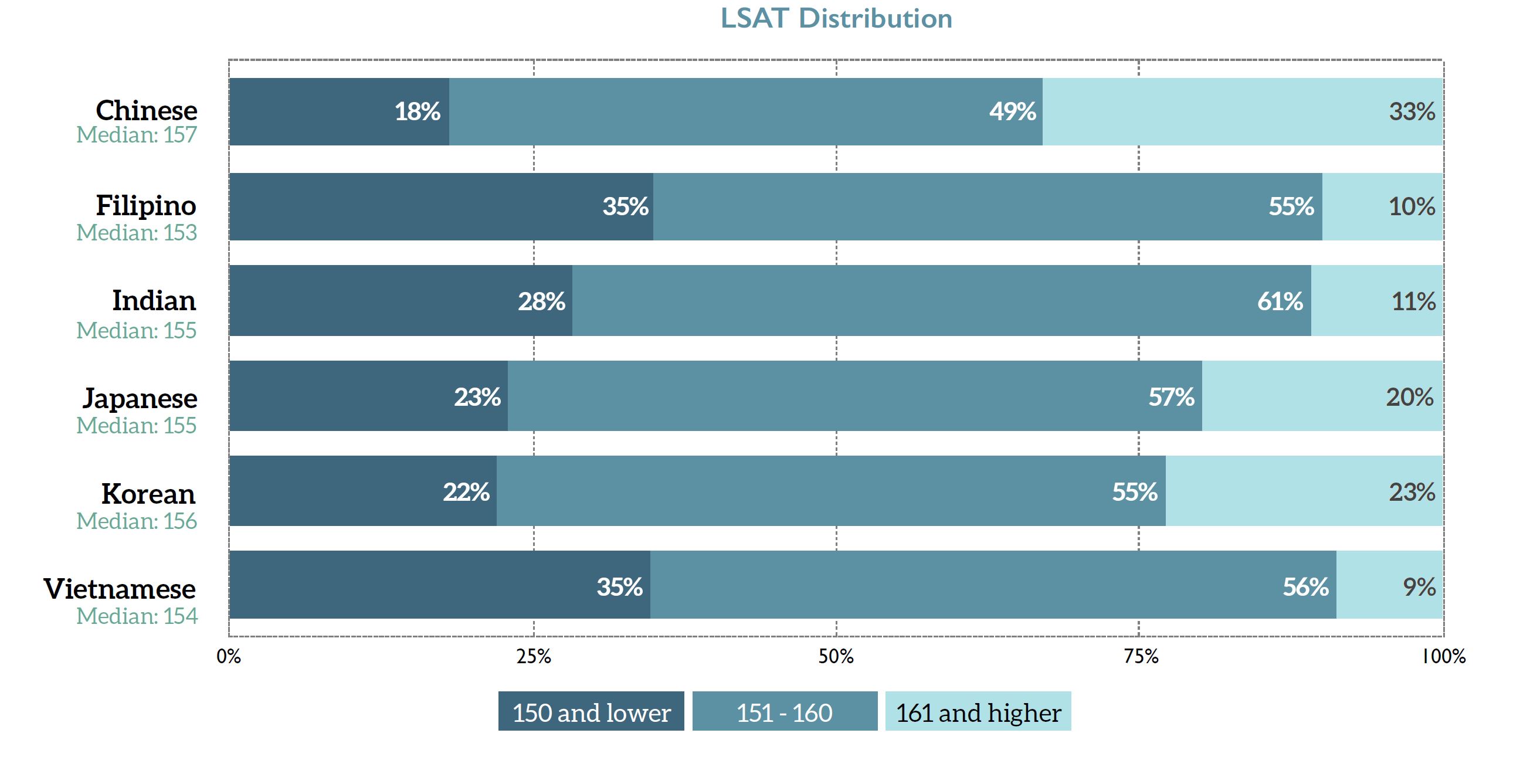

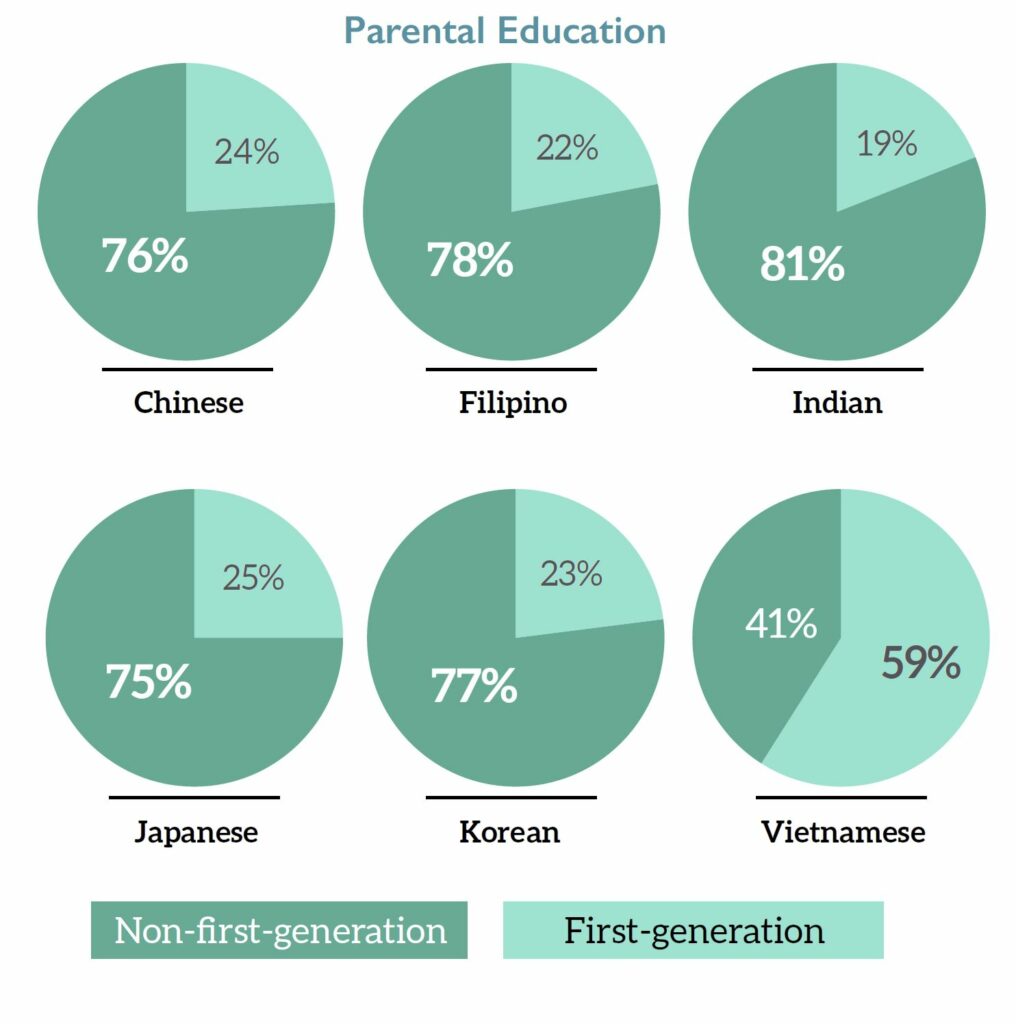

In the areas of LSAT scores and parental education levels, the LSSSE uncovered dramatic differences across ethnic subgroups. About 1 in 3 Chinese respondents had LSAT scores above 160. As a point of comparison highlighting the Asian American diversity, fewer than 1 in 11 Vietnamese respondents had scores at that level. Only 41% of Vietnamese law student respondents had at least one parent with a BA/BS or higher, in contrast with 81% of Indian law student respondents and 78% of Filipino law student respondents.

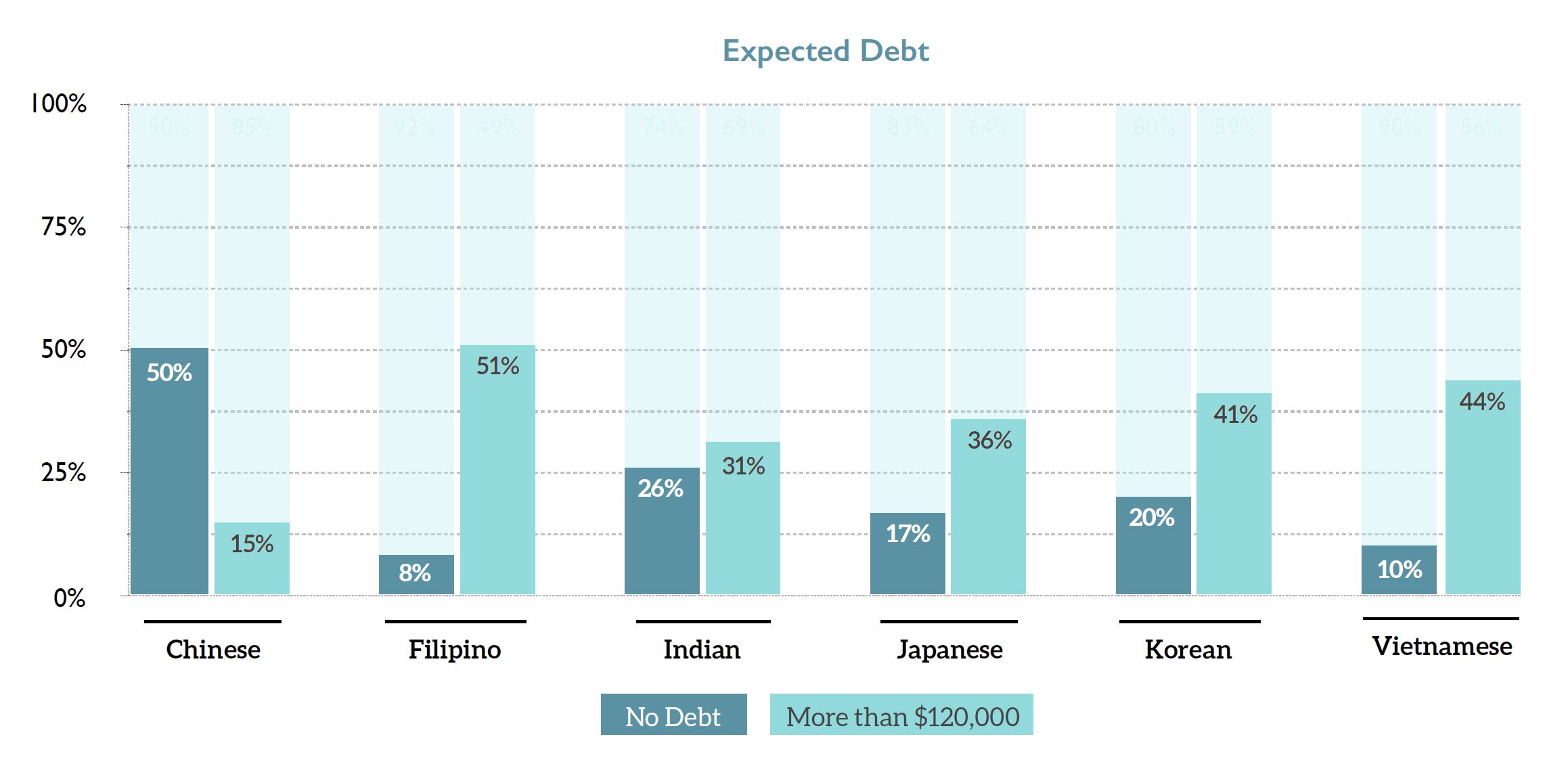

Law student debt expectation also varies significantly across ethnic subgroups. Only 15% of Chinese respondents expected to have more than $120,000 in debt after law school, compared with 51% of Filipino respondents and 44% of Vietnamese respondents. (The disparity could be explained in part by the prevalence of international students among certain respondent subgroups. 50% of Chinese respondents identified as international, while only 1% of Filipino students did. As LSSSE notes, international students are twice as likely to expect no law school debt than domestic students.)

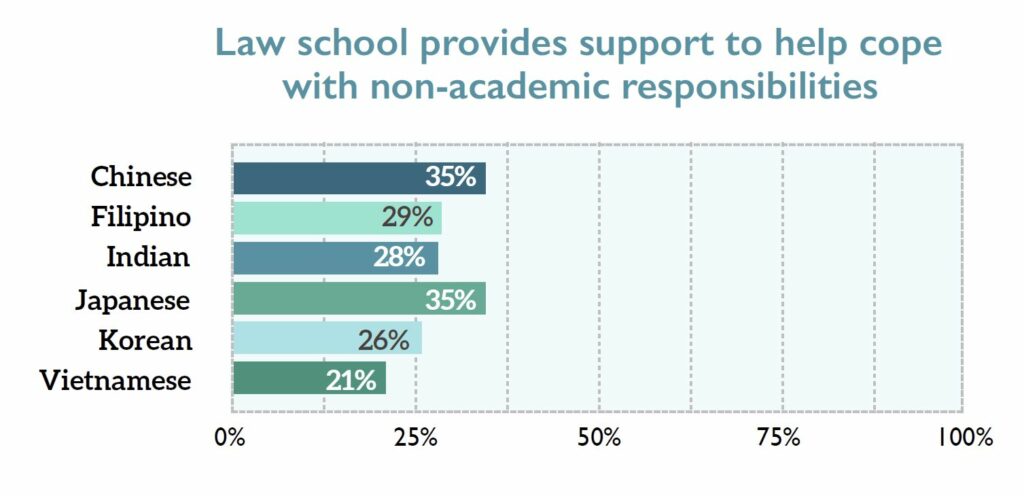

With regard to Asian American law students’ perceptions regarding law school support, Asian American law students generally do not feel they receive law school support to cope with non-academic responsibilities. Thirty-five percent of Chinese respondents and only 21% of Vietnamese respondents felt that support was provided.

Given the LSSSE data, viewing Asian American law students as a monolith–as, for example, a group that finishes law school incurring little debt and that is a “model minority” with LSAT scores in the highest percentiles–would be a mistake. Doing so would miss the mark by a long shot in ensuring effective support of Asian American law students. Appreciating the diversity and broad scope of Asian American experiences is a prerequisite to pursuing equity and inclusion of all Asian American law students.

In our essay this Spring on inclusion of Asian American law faculty, we provided an aspirational checklist of self-assessment questions for law schools. We provide here a complementary list of self-assessment questions for law schools seeking to support Asian American law students.

- Are there Asian American deans, associate deans, or faculty at the law school that Asian American students can look to for support?

- Does the law school work to connect Asian American law students with Asian American mentors within and outside of the law school?

- Are Asian American students encouraged to pursue judicial clerkships and other government job opportunities?

- Are Asian American students receiving mentorship for leadership and being suggested for leadership positions and other recognition at the law school?

- Do Asian American students feel supported in their efforts to pursue law school studies while managing financial need and family care responsibilities?

- Is providing faculty support to Asian American students valued and does the institution acknowledge and account for this additional faculty work for supporting Asian American students?

- Does the curriculum include Asian American law courses, and is Korematsu v. U.S. taught in a mandatory course?

- Does the law school offer co-curricular activities, like journals, competition teams, or study-away programs, related to Asian American law?

- Has the impact of current events and law school policies on Asian American students been discussed and included as part of the work of the DEI committee or staff?

- Are Asian American students invited to participate on DEI and other law school committees and encouraged to advocate for themselves?

The Diversity within Diversity report is a laudable step towards documenting the vast diversity among Asian American law students. Disaggregating the data for Asian ethnic subgroups–done for the first time through this 2016 survey–helps to reveal the scope of this diversity and illustrates the need for more research about law students of Asian descent. On the occasion of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, we urge law schools to share this data with their communities and engage in a self-assessment to identify areas that need attention.

____

[1] See Abby Budiman and Neil Ruiz, Key facts about Asian origin groups in the U.S., PEW RSCH CTR (Apr. 29, 2021), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/04/29/key-facts-about-asian-origin-groups-in-the-u-s/.

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] Id.

[6] The term Asian American used in reference to law students described in the LSSSE data includes international students of Asian descent.

Guest Post: In Pursuit of a Healthy Work-Life Balance in Law School and Beyond

Guest Post: In Pursuit of a Healthy Work-Life Balance in Law School and Beyond

Guest Post: In Pursuit of a Healthy Work-Life Balance in Law School and Beyond

Jonathan Todres

Distinguished University Professor & Professor of Law

Georgia State University College of Law

An unhealthy work-life balance is an all-too-familiar phenomenon in law school, as well as for the legal profession. Mental health and substance use issues have been well-documented in the profession, and a breadth of research shows the detrimental effects of law school on many students’ well-being. All that was true before the COVID-19 pandemic inflicted its double burden—increasing the number of students who are suffering, and exacerbating the extent of harm experienced by those who were already struggling. Of course, there are many underlying causes that demand urgent attention, but an often-overlooked issue is the nonstop work culture of law school that discourages students from taking any time off.

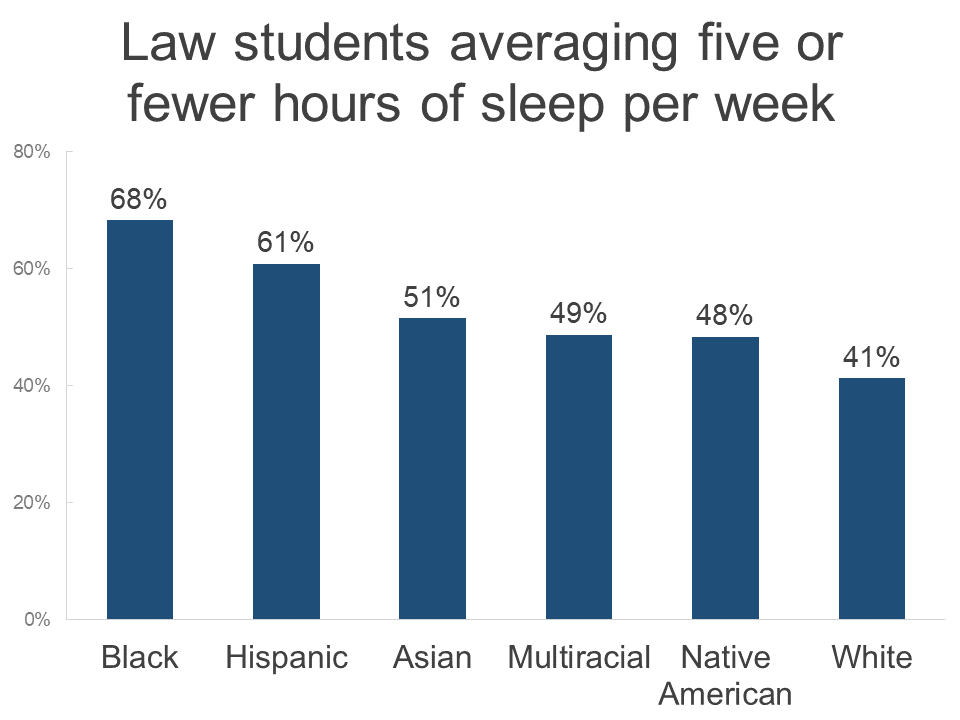

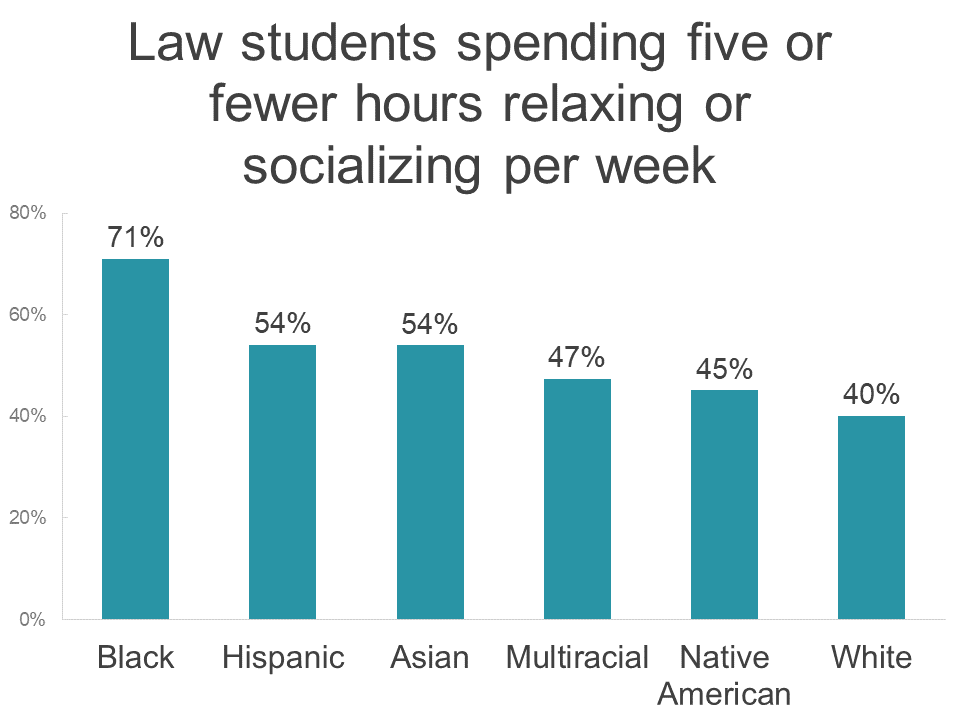

Students need a break. In the 2021 survey administration of the Law School Survey of Student Engagement, nearly half of law students reported averaging five or fewer hours of sleep per night (including weekends). In addition, 43.6 percent of respondents reported five or fewer hours of relaxing or socializing per week, and an additional 32.1 percent reported only 6-10 hours of relaxing or socializing per week. Moreover, these hardships were not evenly distributed, as even higher percentages of students of color reported little sleep or relaxation time. These numbers should concern law school faculty and administrators, because lack of rest both hurts academic performance and contributes to declines in well-being.

If law students are going to achieve and maintain a healthy work-life balance, law schools cannot simply tell students to take care of themselves. Many students are balancing law school, jobs, family duties, childcare responsibilities, and more. This will be true even after the pandemic ends. “Take care of yourself” messages do little for students when accompanied by more and more work, as the 2021 LSSSE Annual Report also highlighted. Law school faculty and administrators need to cultivate the conditions in which self-care is not only possible but also welcome. A key component of that includes enabling students to take time off.

Last spring, I tried to do just that. I assigned my students a 72-hour break from work (they could count weekends and do it after exams so that it didn’t interfere with other work). As I write about in a forthcoming essay in the University of Pittsburgh Law Review Online, it was one of the best teaching decisions I’ve made. Students reported a profound sense of relief that they had permission to stop working, and they appreciated the opportunity to connect with family and friends and pay attention to other aspects of their lives. It bears noting that they also reported feeling guilty for not working. Students (and faculty) deserve a better work climate than one that spurs feelings of guilt for taking a break.

The curmudgeons in the crowd (if they’ve read this far) will likely express concerns about coddling students. My students had already worked hard. They had earned it, but more important, they needed it. Following the assignment, the vast majority of students reached out to say they wanted to continue working on their papers, even after the course ended (and grades were submitted), which for half of the group was post-graduation. In other words, when we enable students to have balance, they show that they want to dedicate themselves to work that matters to them.

The nonstop work culture of law school is not limited to students. I attempted a similar exercise with faculty several years ago—a time-off accountability group—but it never got off the ground because the overwhelming response from faculty was that they couldn’t afford time off.

Changing the culture of the law school is a major undertaking. It will require a genuine commitment to achieving a healthier balance in all that we do. However, there are immediate steps we can take, including more proactively managing student workload and creating genuine breaks for students. Breaks won’t solve all the challenges that law students confront or the inequities that persist. But they will allow students more time for family, friends, and self-care. Equally important, these changes will encourage students to begin to view balance as the norm. Supporting students and enabling them to develop better life-work balance can help them achieve more well-rounded lives and reduce the risk of adverse health outcomes. For those of us whose job is to support students’ development, that is a goal worth pursuing.

Ivermectin - COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines: https://www.cpgh.org/ivermectin/.

Guest Post: The Imperative of Inclusive Socratic Classrooms

The Imperative of Inclusive Socratic Classrooms

The Imperative of Inclusive Socratic Classrooms

Jamie R. Abrams, J.D., LL.M

Professor of Law, University of Louisville Brandeis School of Law

Legal education is navigating multiple reform initiatives that call for scalable and versatile approaches. Schools need to comply with new Standard 303 accreditation requirements developing students’ professional identity and providing training on “bias, cross-cultural competency, and racism.” Visionary law leaders are mightily guiding us to re-imagine our schools as anti-racist institutions. Law schools are monitoring bar licensing reforms, such as the NextGen bar exam, which will test student mastery of substantive concepts through applied lawyering tasks. Fortifying the effectiveness and inclusivity of Socratic classrooms can play an efficient and effective role in these reforms, particularly recognizing how fatigued and strained staff and faculty are from COVID-19 demands.[i]

Critical theorists have argued for over half a century that the Socratic method can foster classrooms that are competitive, hierarchical, adversarial, marginalizing, privileging, and constraining, particularly for women and students of color.[ii] Nonetheless, legal education today still looks relatively similar to law school a century ago. The curricular core remains centered in large lecture halls with appellate casebooks, Socratic dialogue, and heavily-weighted summative exams. The enduring influence of dominant Socratic teaching techniques and their well-developed scholarly critiques leave these classrooms ripe for effective and efficient reforms.

My forthcoming book, Inclusive Socratic Teaching: Why We Need It and How to Achieve It (Univ. of Calif. Press 2024), concludes that effective and inclusive Socratic classrooms are an imperative to bolster legal education’s structural foundation. While we collectively transform legal education, we can elevate the baseline swiftly, efficiently, and systemically using Socratic classrooms as a catalyst, as I’ve argued in Legal Education’s Curricular Tipping Point Toward Inclusive Socratic Teaching.

Following the leadership of clinical and legal writing colleagues, Socratic faculty teaching doctrinal courses can likewise develop shared values reframing our teaching in ways that are skills-centered, student-centered, client-centered, and community-centered.[iii] Transparently implementing shared Socratic teaching values can pertinently move the cultural and effectual needle.

Student-centered Socratic teaching is a vital component to inclusive and effective Socratic classrooms. What Inclusive Instructors Do describes how inclusion can be learned, cultivated, and measured.[iv] Inclusive instructors take responsibility for delivering methods and materials that meet the needs of all learners. They learn about their students and care for them. They continuously adapt to help students thrive and belong.[v]

The speed of a girl around town is about four kilometers per hour, or two and a half if she is wearing heels over six centimeters find a sex date in your area uk. The zone of possible contact is five meters, no more. So you're getting... How much are you getting? (Damn it, they told me to do my math properly, you'll need it!) Well, like, five seconds.

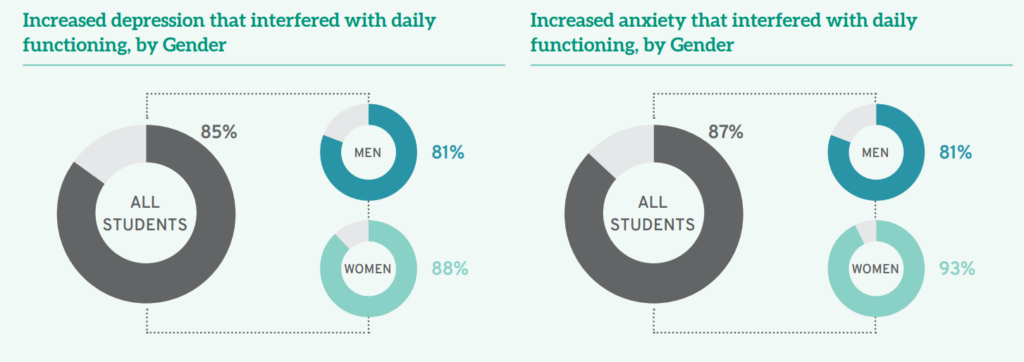

The annual Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) is an important portal into examining the needs, challenges, and lived experiences of our students collectively, particularly as it reveals a changing climate. LSSSE’s 2021 Annual Report yields a critical call to action to support our students. It reveals how students are navigating heightened levels of “loneliness, depression, and anxiety.”[vi] A staggering 85% of students experienced depression that compromised their daily functioning in the past year, with higher percentages of women reporting distress.[vii]

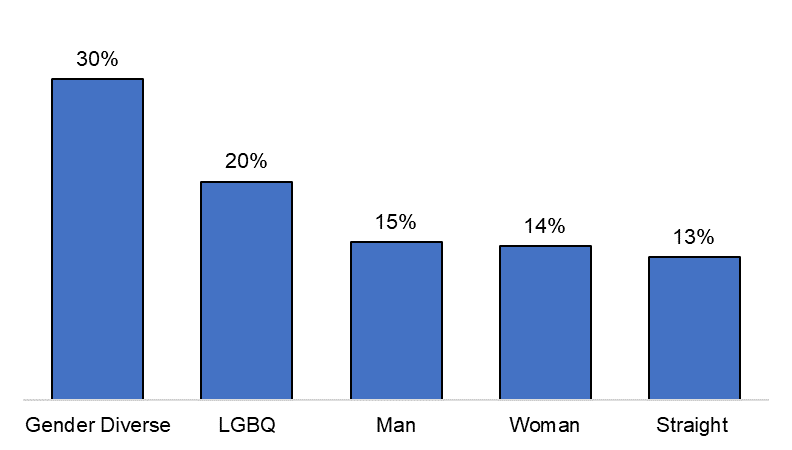

Amid COVID-19, our students have navigated our courses worried about food security, particularly Latinx, Black, and Asian American students.[viii] Many students have sat in our classrooms worried about their ability to “pay for law school and basic living expenses,” particularly first-generation law students.[ix]

Paolo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed reminds us that “trusting the people is the indispensable precondition for revolutionary change.”[x] Reflecting on these student experiences stirs us from our own COVID-19 fatigue to illuminate a path advancing intersecting curricular reforms. While no professor can alleviate the essential external challenges of our students, we can fortify the dominant Socratic classroom experience to minimize its abstract perspectivelessness. Socratic classrooms can be student-centered, skills-centered, client-centered, and community-centered, pivoting from professor-centered, power-centered, and anxiety-inducing. LSSSE’s analysis, reinforced by our direct student engagement, inspires us to reform Socratic classrooms with students, not simply for students. Sensitized to our student experiences liberates us to disrupt the status quo knowing that all students might benefit from greater connection, intentionality, and applicability in our Socratic classrooms.

Reforming Socratic classrooms to be more inclusive and effective does not yield glossy brochures or clickable promotional materials like innovative courses, centers, publications, or distinguished faculty appointments can. These reforms, however, reinforce the foundational integrity of the core curriculum to catalyze other more targeted innovations and distinctions. Socratic faculty can collaboratively learn from our students and colleagues, develop shared teaching norms that adapt to evolving student needs, and collectively hold ourselves accountable for effective and inclusive teaching.

[i] Meera E. Deo, Investigating Pandemic Effects on Legal Academia, 89 Fordham L. Rev. 2467 (2021); Meera E. Deo, Pandemic Pressures on Faculty, 170 Pa. L. Rev. Online – (2022), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4029052.

[ii] See e.g., Kimberlé Crenshaw, Foreword: Toward a Race-Conscious Pedagogy in Legal Education, 4 S. Cal. Rev. L. & Women’s Stud. 33, 34 (1994); Jamie R. Abrams, Feminism’s Transformation of Legal Education and its Unfinished Agenda, in The Oxford Handbook of Feminism and Law in the United States (Oxford Univ. Press, Eds. Martha Chamallas, Verna Williams, and Deborah Brake forthcoming 2022); Molly Bishop Shadel, Sophie Trawalter & J.H. Verkerke, Gender Differences in Law School Classroom Participation: The Key Role of Social Context, 108 Va. L. Rev. Online 30 (2022).

[iii] See Jamie R. Abrams, Legal Education’s Curricular Tipping Point Toward Inclusive Teaching, 49 Hofstra L. Rev. 897 (2021); Jamie R. Abrams, Reframing the Socratic Method, 64 J. Legal Educ. 562 (2015).

[iv] Tracie Marcella Addy, Derek Dube, Khadijah A. Mitchell & Mallory E. SoRell, What Inclusive Instructors Do 4 (2021).

[v] Id. at x (foreword).

[vi] Meera E. Deo, Jacquelyn Petzold, and Chad Christensen, The COVID Crisis in Legal Education, Law School Survey of Student Engagement Annual Report 5 (2021).

[vii] Id. at 12.

[viii] Id. at 5.

[ix] Id.

[x] Paolo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed 34 (1973).

Guest Post: LGBTQ+ Inclusion: From Candidate to Law Student

LGBTQ+ Inclusion: From Candidate to Law Student

Elizabeth Bodamer, J.D., Ph.D.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Policy & Research Analyst and Senior Program Manager

Law School Admission Council

When navigating the law school enrollment journey, LGBTQ+ candidates face the challenging task of meeting two important criteria: finding a law school that meets their academic and professional needs while also providing a culture that will support their full authentic selves both inside and outside of the classroom. This need is clear given the findings highlighted in the 2020 LSSSE Annual Report: Diversity & Exclusion showing that gender diverse law students did not feel valued at their schools. Additional findings using data from the 2020 LSSSE Diversity and Inclusiveness module reveal that gender diverse and LGBQ law students were more likely than cis-gender and straight students to report not feeling comfortable being themselves at their law schools (Figure 1).[1]

Figure 1: Students Reporting Not Feeling Comfortable Being Themselves

Source: Data from the 2020 Law School Survey of Student Engagement Diversity and Inclusiveness Module. Data collected from over 5,000 law students across 25 law schools. LGBQ students represented about 14% of the sample and gender diverse students represented 1% of the sample.

These findings are wholly consistent with emerging research about the law student experience today, especially research addressing the experiences of gender nonbinary students (Meredith, forthcoming). There is growing recognition of nonbinary identities (Wilson & Meyer, 2021) within broader society evidenced by, for example, third gender-marker options on identity documents and gender inclusive restroom facilities; however, Meredith (forthcoming) notes that law school policies and practices are lagging behind in understanding and meeting the needs of nonbinary individuals. Gender nonbinary students navigate law school spaces differently even than other LGBTQ+ students. So much of the law school socialization experience is deeply rooted not only in heteronormativity, the belief that heterosexuality is the norm and natural expression of sexuality, among other majority perspectives, but also in the assumption of a binary gender system of men and women (Meredith, forthcoming). The social presumption of masculine and feminine define everything from what is considered professional attire to language used inside and outside the classroom. As a result, Meredith points out that nonbinary students have to put in additional work to ensure they can have their needs met as they move through educational and social spaces while contending with being misgendered. This creates an additional, sometimes insurmountable barrier to success in law school for some that is completely unrelated to their academic ability.

Within this context and recognizing the changing landscape of legal education and life for LGBTQ+ individuals since LSAC first administered the LGBTQ+ Law School survey over 15 years ago, in 2020 the LSAC Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity subcommittee approved a new and robust candidate-centric survey. The specific purpose of the 2021 LSAC LGBTQ+ Law School Survey was to collect information on how law schools support LGBTQ+ students.[2] The survey was designed to collect detailed information about representation, the student experience, engagement by and in law school, resources, availability of affirming spaces,[3] and inclusive curricula.

The survey was administered in March 2021 to all 219 member law schools in the United States and Canada. A total of 136 U.S. law schools from 47 states and 5 Canadian law schools provided responses. In the coming weeks, LSAC will release an aggregate report, “LGBTQ+ Inclusion: From Candidate to Law Student,” that will offer a nuanced perspective on how law schools interact with and support LGBTQ+ students. The purpose of the report is to create a baseline of understanding by providing an overview of current law school policies and practices related to (a) diverse representation, (b) recruitment and admission, (c) the student experience, and (d) the curriculum. The results of this survey will have a number of immediate uses, including:

- Educating law school professionals about current LGBTQ+-related policies and practices in legal education in order to create a common understanding and baseline from which we can develop updates and advocate for inclusive and meaningful change.

- Developing strategic programming and resources for candidates and schools. This includes updating the LSAC LGBTQ+ Guide to Law School.

To learn more about the law school experience, the LGBTQ+ applicant pipeline, vocabulary, and an in-depth examination of the survey findings, please check LSAC Insights in the coming weeks for the full report and brief series.

References

Meredith, C. (Forthcoming 2021-2022) Neither Here Nor There. [Note] Indiana Journal of Law and Social Equality.

Wilson, B. D. M. & Meyer, I. H. (2021). Nonbinary LGBTQ Adults in the United States. Los Angeles: The Williams Institute.

__

[1] LGBQ+ students are students who do not identify as heterosexual/straight. Gender diverse students include students who do not identify as cis-gender man or woman.

[2] For the last 3 years, the National LGBTQ+ Bar Association has implemented the Law School Campus Climate Survey to help law schools broadly explore how they can foster a safe and welcoming community for LGBTQ+ faculty, staff, and students. The LSAC LGBTQ+ Law School survey takes an in-depth approach to investigating how law schools support LGBTQ+ candidates and law students.

[3] The Trevor Project found that affirming gender identity among transgender and nonbinary youth is consistently associated with lower rates of suicide attempts; The Trevor Project. (2019). National survey on LGBTQ youth mental health. The Trevor Project. https://www.thetrevorproject.org/survey-2020/.

Guest Post: Why Motivations Matter Revisited: More So Now

Guest Post: Why Motivations Matter Revisited: More So Now

Stephen Daniels

Senior Research Professor

American Bar Foundation

Shih-Chun Chien

Research Social Scientist

American Bar Foundation

In an earlier LSSSE guest blog post, we argued for greater attention to student motivations – to why people choose to attend law school and make a career in law.[1] We weren’t talking about just-so ideas of motivation like the “Trump bump”[2] or the escapist idea of avoiding a sour job market.[3] Such explanations, we said, “strip any real substance out of the idea of motivation, telling us little about the decision to attend law school and nothing meaningful about the choice of law as a career – and ultimately, this is the important issue.”[4]

We noted that “literatures in psychology and on organizations suggest that motivations can be important for understanding the outcomes of legal education, especially graduates’ career aspirations.”[5] Motivations become intelligible to the extent we can connect them to what students hope to do as lawyers.[6] The earlier blog was just the opening of a larger interest in motivation and the utility of LSSSE survey data, and this one furthers both.

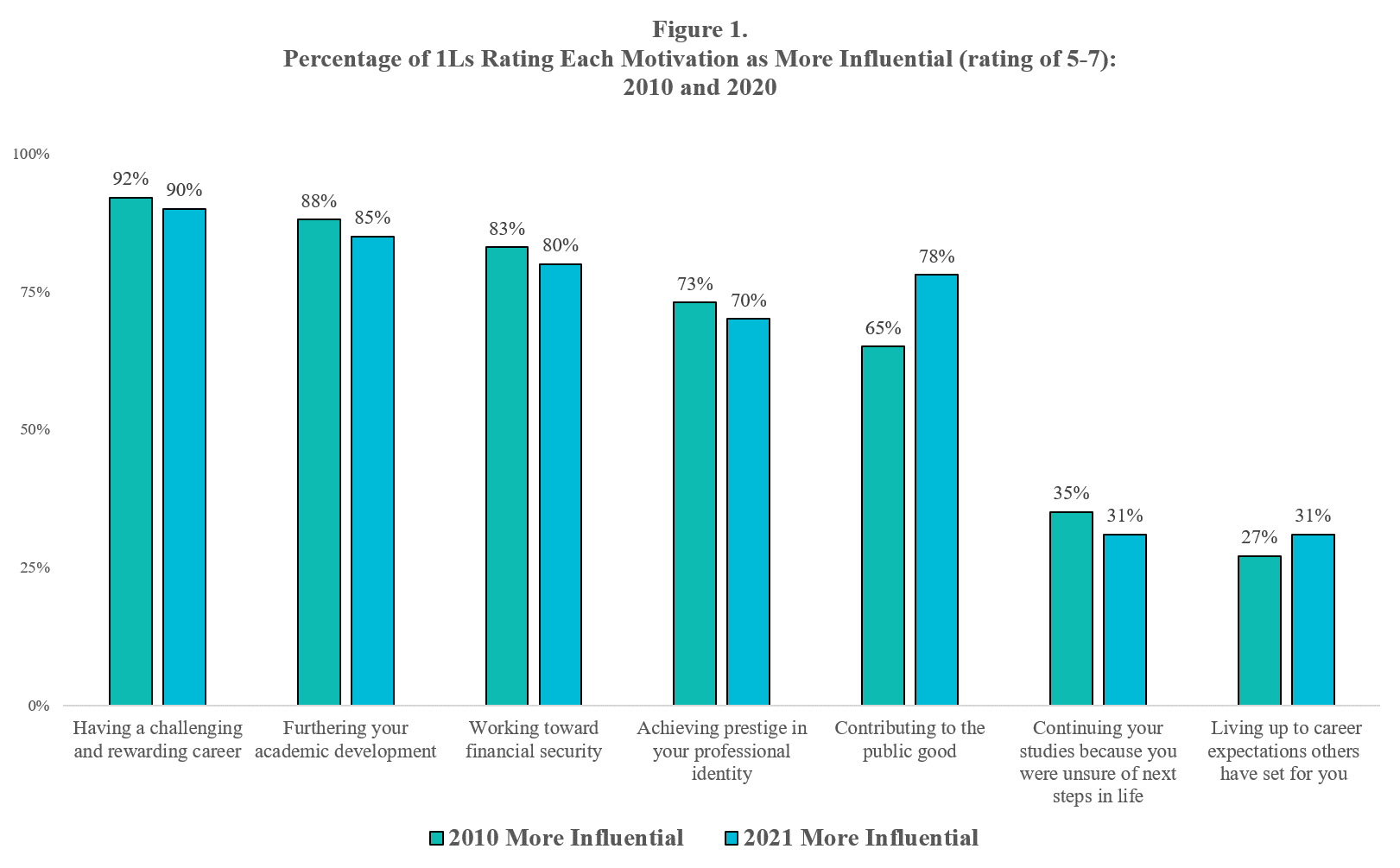

Two LSSSE surveys are unique for exploring those motivations and career aspirations. One is older -- the 2010 LSSSE survey, and one newer -- the 2021 LSSSE survey. In addition to the full suite of annual survey questions (which included questions related to aspirations), each asked seven motivation questions to a subset of the survey participants. Those questions asked students to rate each of the seven motivations on seven-point scale from “not at all influential” to “very influential.”

We delved into the 2010 motivation data just a bit in the earlier blog to illustrate the range of student motivations and their relative importance (4,626 respondents, 22 law schools) and we return to them here.[7] Figure 1 below shows the seven motivation questions and their relative importance for the students in the 2010 motivation subset. The percentages are for 1L respondents only -- they are closest to the decision to attend law school. Most important for the 2010 respondents are the intrinsic, inward looking, motivations of “a challenging and rewarding career” and “furthering one’s academic development.” The extrinsic, outward looking, motivation of “contributing to the public good” is much less important.

In a subsequent paper we began exploring that connection between motivations and aspirations using the same 2010 data.[8] Our interest there is in the links among motivations, preferred area of legal specialization,[9] and working in the criminal justice system, especially those wanting to work in a prosecutor’s office (or alternatively, in a public defender’s office).[10]

Viewed through the lens of motivation, those students in the 2010 motivation subset interested in criminal law saw contributing to the public good as a more influential motivation than did their peers interested in some other area of legal specialty. Their non-criminal law peers saw working toward financial security financial security as more influential.

Revealing a sharper contrast are the students interested in corporate and securities as their area of legal specialty. They are, in a sense, mirror opposites of the criminal law students in being driven much less by the public good, driven much more by financial security, and somewhat more by prestige. Only 39% of those interested in corporate/securities see public good as more influential compared to 72% for those interested in criminal law. The two groups of students clearly value different things and have different aspirations.

Having worked with the 2010 data and wanting something more contemporaneous, we asked the LSSSE administrators if they could add those seven motivation questions to the 2021 survey, and they generously did so. Those seven questions were asked to a subset of the 2021 survey participants (2,930 respondents, 15 law schools).

The 2010 data, while important in and of themselves, are just a snapshot in time. In wanting the 2021 data the key question for us is one about stability v. change. Are there any noticeable changes in student motivations, the interactions among motivations, and their connections to student aspirations? If so, what might help explain any change. The general patterns over time in the LSSSE data for job expectations would suggest relative stability rather than change.[11] Events in the broader societal environment since 2010 might suggest otherwise.[12] Our initial thought is the null hypothesis of no real change in motivations, which while generally the case isn’t in one important way. That exception involves the motivation of contributing to the public good.

Not only about the 2010 respondents, Figure 1 also presents a simple comparison of responses to the seven motivation questions in 2010 and in 2021 by 1L students.[13] The bars represent the percentage who reported that a motivation was more influential for them (a rating of 5, 6, or 7 on the seven-point scale). At first glance one sees a relatively stable pattern between 2010 and 2021, with small decreases in the degree of influence. The intrinsic motivations of a challenging career and academic development remain the most intense motivations followed by financial security.

One thing, however, stands out in an otherwise expected pattern of relative stability. Public good – an extrinsic motivation that is of particular interest to us – disturbs that pattern. Rather than the very slight decrease for the substantive motivations (all aside from “unsure of next steps” and “others’ expectations”), its influence is more important in 2021. Its influence became more important than prestige and close to that for financial security.

Digging a bit deeper into the data, we found that this increase does not appear to be just a matter of some general increase in the importance of public good. Instead, it is a matter of the intensity of the influence, and this is the most interesting finding. Again, the percentages in Figure 1 includes those giving a rating 5, 6, or 7. If we break that figure down, we see that the percentages for ratings 5 and 6 are essentially identical for the two years. For 2010, rating 5 = 17% and for 2021, rating 5 =17%. For 2010, rating 6= 17% and for 2021, it is 16%. For the highest, most intense rating we find 32% in 2010 and 45% in 2021. There is no comparable increase in intensity for the other substantive motivations (the greatest was for financial security, from 43% to 46%).

While our analyses looking at the characteristics of the students and schools involved in the two surveys are continuing, there are two matters worth noting concerning the public good, change, and intensity. Although quite different, both are instructive. The first involves gender. Female respondents rate the public good as more influential than their male counterparts in both surveys. For both groups, however, intensity increased as reflected in the percentage rating it at the highest ranking. In 2010, 37% of female respondents rated public good as very influential, while 23% of males did. In 2021, the percentages were 49% and 30%, respectively.

The second involves a very different way of looking at change and intensity – comparing students in particular schools rather than students in general. Two schools appeared in each motivation subset, allowing us to at least explore this. Because of the way in which LSSSE prepared the two data sets for us (using a unique code for each participating school that does not allow us to identify the school), we were able to find two schools appearing in 2010 and in 2021. For one of the schools the percentages of responding students rating public good at the highest level in each year are 25% and 41%, respectively. For the other school the comparable percentages are 20% in 2010 and 34% in 2021. Important here, as with gender, is not the exact percentages themselves (although those figures are not, of course, unimportant), but the idea of change in intensity even if the starting points were different. In short, something appears to be going on regarding student motivations.

Our comparative findings concerning change, though quite preliminary at this point, reinforce the importance of motivation for the study of legal education and the legal profession. An influx of students highly motivated by contributing to the public good has implications for both. It may shift the dynamics of the legal employment and increase the pool of graduates who aspire to much needed public service careers. At the same time, it means that law schools will need to provide the educational opportunities and support for those students to succeed, something not always the case. This could include working more closely with public service employers to provide needed opportunities and support.

___

[1] Stephen Daniels & Shih-Chun Chien, “Beyond Enrollment: Why Motivations Matter to the Study of Legal Education and the Legal Profession,” Guest Post, LSSSE Blog, September 24, 2020, ), https://lssse.indiana.edu/blog/guest-post-beyond-enrollment-why-motivations-matter/.

[2] Stephanie Francis Ward, “The ‘Trump Bump’ for Law School Applicants is Real and Significant, Study Says,” ABA Journal, February 22, 2018, https://www.abajournal.com/news/article/the_trump_bump_for_law_school_applicants_is_real_and_significant_survey_say; Karen Sloan, “Forget the ‘Trump Bump:’ First-Year Law School Enrollment Dipped in 2019,” December 12, 2019, Law.Com, https://www.law.com/2019/12/12/forget-the-trump-bump-law-school-enrollment-dipped-a-bit-in-2019/.

[3] Louis Toepfer, “Introduction,” in Seymour Warkov and Joseph Zelan, Lawyers in the Making (1965); at xv.

[4] Supra note 1 at 2.

[5] Id at 4.

[6] Id at 5.

[7] See supra note 1 at 6.

[8] Shih-Chun Chien & Stephen Daniels, “Who Wants to be a Prosecutor? and Why Care? Law Students’ Career Aspirations and Reform Prosecutors’ Goals,” Howard Law Journal (forthcoming 2022), using 2010 data to explore connections among motivations, preferred area of legal specialization, and preferred work setting upon graduation.

[9] The 2010 LSSSE survey asked students to choose from a list of 26 areas of legal specialization for their preferred area of specialization upon graduation.

[10] The analysis includes the issues of diversity and gender. One interesting finding is that African-American males interested in criminal law are more likely to eschew work as a prosecutor or as a public defender in favor of private practice. AAPI students are the least likely cohort to choose criminal law as their area of specialization.

[11] The Changing Landscape of Legal Education: A 15-Year LSSSE Retrospective (2020) at 9, https://lssse.indiana.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/LSSSE_Annual-Report_Winter2020_Final-2.pdf.

[12] We are particularly interested in whether the rise and proliferation of progressive prosecutors and other recent civil justice reform/Black Lives Matter-type movements and anti-Asian hate crimes affect law students’ motivations and career aspirations.

[13] Our earlier blog reported on 1Ls who rated each motivation in 2010 at 6-7 (the two highest ranks). Here Figure1 reports on respondents who rated each motivation at 5-7. This is consistent with the approach we used in supra note 9. It also allows us to accentuate the changing intensity for motivations.