A CRT Assessment of Law Student Needs

Meera E Deo, JD, PhD

Meera E Deo, JD, PhD

The Honorable Vaino Spencer Professor of Law, Southwestern Law School

Director, Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE)

For over a century, American policy makers have recognized the need to provide personal support to students in primary and secondary school. Many states, including California, offer free or reduced lunch to students in need. Nurses and counselors are often available on campus to provide medical attention, academic guidance, and mental health support. Despite our clear understanding of the importance of these structures of support for children in the K-12 educational system, there are few mechanisms to support students in higher education. Yet many students in college, graduate school, and professional school also struggle to meet their basic needs.

In my new article, “A CRT Assessment of Law Student Needs,” and the accompanying Fact Sheet, I seek to convince policymakers that law students also need both administrative and legislative support to help them survive and thrive academically as well as professionally. LSSSE data show law students have been struggling to recover from the heightened challenges they endured during the early years of the pandemic. Struggles with food insecurity, financial anxiety, and emotional strain contribute to declining academic success, particularly for populations that were marginalized on law school campuses long before COVID. Legislative support is necessary to support students through this era so they can maximize their full potential.

Applying a CRT Framework

When we consider the CRT tenets of intersectionality and the compound effects resulting from those with devalued raceXgender characteristics specifically, it becomes evident that women of color law students are particularly at risk of falling behind or leaving law school altogether without greater support. The CRT concept of praxis further urges scholars to not only theorize about challenges and opportunities, but to put proposals into practice to achieve real change. Merging empirical methods with CRT, a new model of eCRT scholars “seek to rethink and change the premise of race scholarship in general by eschewing theoretical and methodological silos in pursuit of deepening our understanding of race and racism to advance racial justice.” Here, LSSSE data coupled with CRT theories are particularly instructive.

LSSSE Findings on Law Student Needs

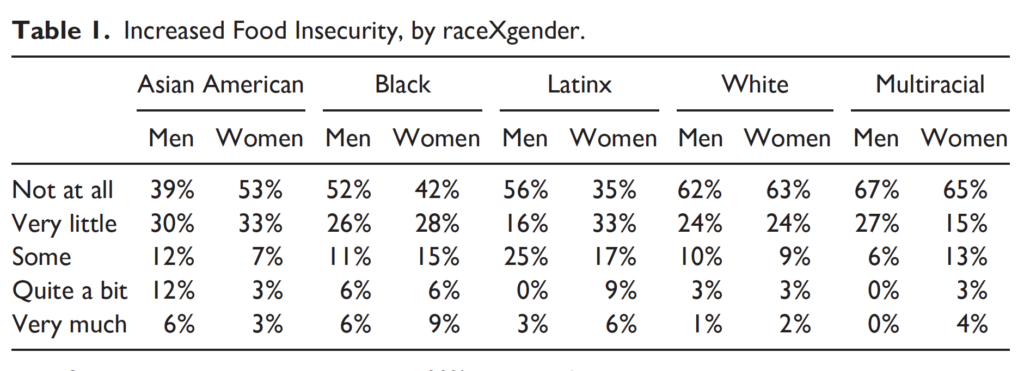

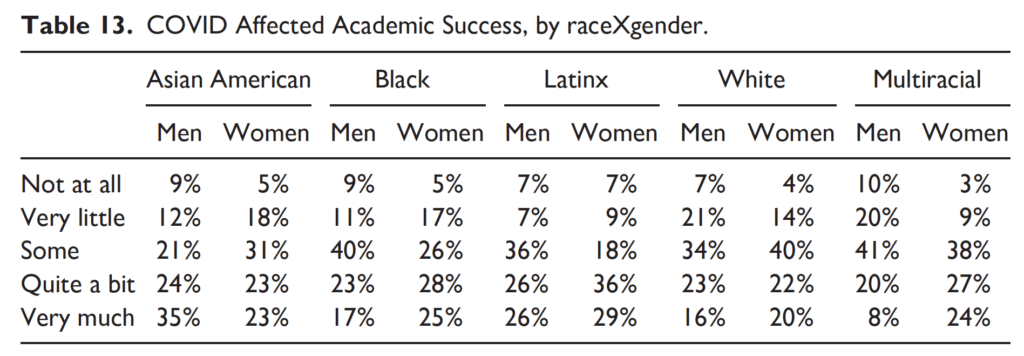

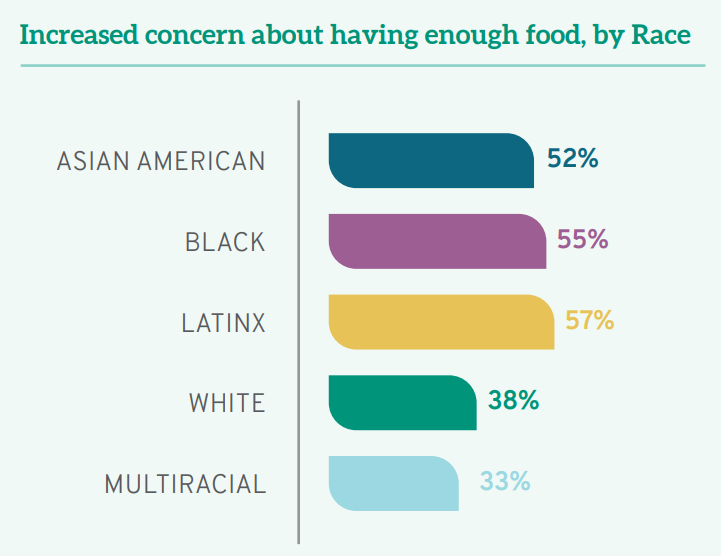

In 2021, LSSSE asked students about their experiences Coping with COVID. What they shared remains deeply disturbing, and even more so when we consider raceXgender effects. Women of color suffered with high levels of food insecurity—including 58% of Black women and 65% of Latinas who had increased concerns about whether they had enough food to eat.

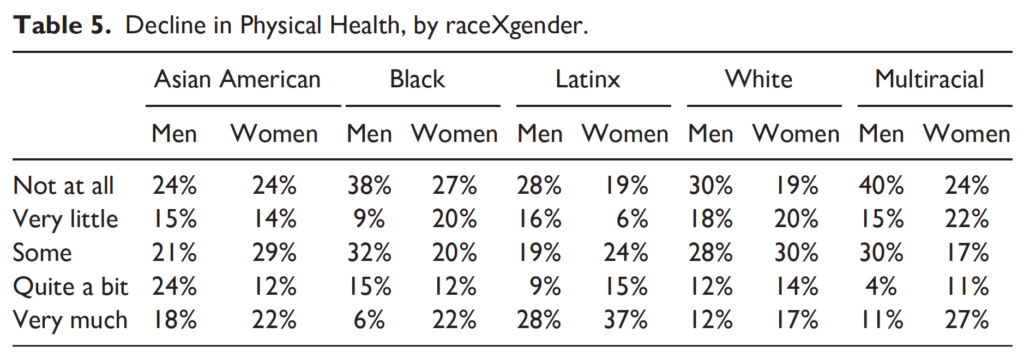

Students also reported declines in their physical health. For every racial group, higher percentages of women than men noted these declines—including 81% of Latinas (and 72% of Latino men).

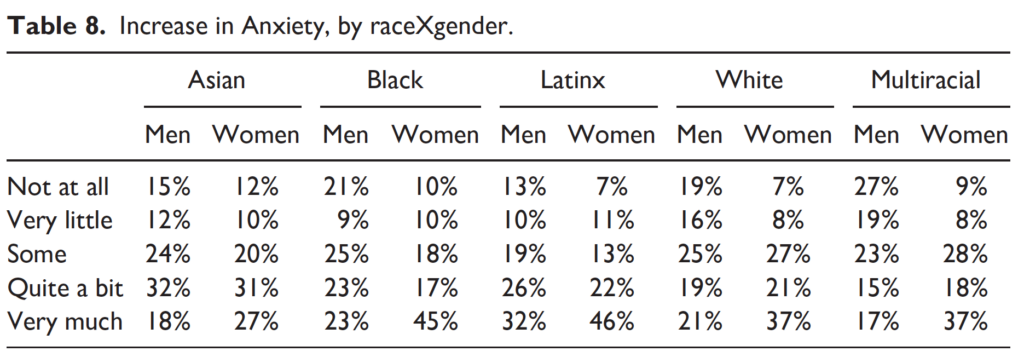

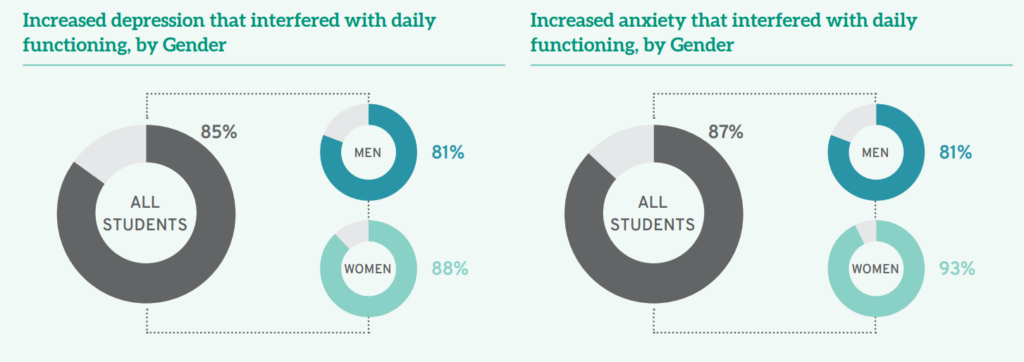

Most students also managed depression (85%) and anxiety (87%) that interfered with daily functioning—again, with marked raceXgender effects that bear out the CRT literature. For instance, while 73%–81% of white men, Black men, and multiracial men reported increased anxiety, a full 93% of white women, 90% of Black women, and 91% of multiracial women experienced the same.

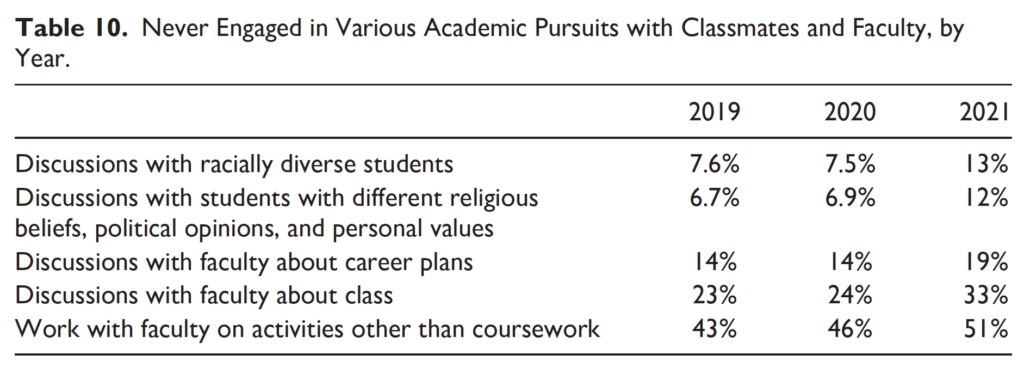

Struggles to meet their basic needs resulted in numerous missed opportunities for interaction with classmates and professors. One out of every five student respondents to the 2021 LSSSE survey (19%) never spoke with professors or other advisors about career plans or their job search. One third (33%) never discussed ideas from readings or classes with faculty members outside of class. There were also fewer opportunities for students to work with faculty on activities other than coursework (including committees, orientation, and student life activities); a full 51% of students never worked with faculty on these projects outside of class. Unsurprisingly, given all of these struggles, students also reported decreases in academic success, with women from most racial groups suffering more than men.

Institutional and Legislative Support

Most institutions already have a foundation to support students. But we can do better. In “A CRT Assessment of Law Student Needs,” I propose numerous options for administrators and policymakers to consider. For instance, while many campuses have food pantries to combat food insecurity, they should go beyond a locked room full of cans to prioritize accessibility by being open long hours or 24 hours, without an appointment or sign-in requirement, and on various parts of campus (not just one location that may be difficult for law students to access). Drawing from the CRT literature, food pantries should stock not only canned goods but also gift cards so students from varying backgrounds can purchase traditional or ethnic foods and fresh fruits and vegetables, and otherwise have agency over their food consumption.

Given increases in student anxiety and depression, law schools also should make mental health counseling available—with a focus on quality and accessibility for vulnerable populations. Counseling sessions should be free or low cost, with appointments scheduled via phone or through the click of a button, and meetings available both in person and online, as telehealth enables students of color—who rarely have on-site counseling available from professionals of their racial or cultural background—to connect online with counselors who work better for them.

Beyond institutional support, law students need legislative support. This is why the article includes an accompanying Fact Sheet—to make clear through brief bullet points and visualizations what the challenges are and how policymakers can help. Legislators could immediately reduce food insecurity by permanently expanding Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits to law students—without requiring them to work 20 hours per week or prove they care for dependents. Both the EATS Act and the Student Food Security Act provide pathways for SNAP expansion and extension; they are currently pending before Congress and should be strongly supported. California recently passed legislation expanding CalFresh (the state SNAP program) to those enrolled in institutions of higher education at least half-time. Other states should follow suit. Similarly, legislation should ensure mental health care is covered in standard insurance policies that tend to focus on physical health. Legislation could also offer financial assistance to institutions providing integrated mental health counseling for free or low-cost to law students. Additional legislative support could offer rental assistance, loan forgiveness, emergency funds, and other resources to law students in need.

Conclusion

Together, administrators and legislators can work to combat barriers facing law students that have intensified as a result of COVID. Once their basic needs are met, students can turn to maximizing their academic and professional success. Part of student success involves effectively and enthusiastically engaging in the intangibles of legal education, drawing from their own experiences and backgrounds to share and learn from classmates and faculty. When students are overcome by anxiety, depression, and loneliness, it is impossible to perform at their best.

Guest Post: The Imperative of Inclusive Socratic Classrooms

The Imperative of Inclusive Socratic Classrooms

The Imperative of Inclusive Socratic Classrooms

Jamie R. Abrams, J.D., LL.M

Professor of Law, University of Louisville Brandeis School of Law

Legal education is navigating multiple reform initiatives that call for scalable and versatile approaches. Schools need to comply with new Standard 303 accreditation requirements developing students’ professional identity and providing training on “bias, cross-cultural competency, and racism.” Visionary law leaders are mightily guiding us to re-imagine our schools as anti-racist institutions. Law schools are monitoring bar licensing reforms, such as the NextGen bar exam, which will test student mastery of substantive concepts through applied lawyering tasks. Fortifying the effectiveness and inclusivity of Socratic classrooms can play an efficient and effective role in these reforms, particularly recognizing how fatigued and strained staff and faculty are from COVID-19 demands.[i]

Critical theorists have argued for over half a century that the Socratic method can foster classrooms that are competitive, hierarchical, adversarial, marginalizing, privileging, and constraining, particularly for women and students of color.[ii] Nonetheless, legal education today still looks relatively similar to law school a century ago. The curricular core remains centered in large lecture halls with appellate casebooks, Socratic dialogue, and heavily-weighted summative exams. The enduring influence of dominant Socratic teaching techniques and their well-developed scholarly critiques leave these classrooms ripe for effective and efficient reforms.

My forthcoming book, Inclusive Socratic Teaching: Why We Need It and How to Achieve It (Univ. of Calif. Press 2024), concludes that effective and inclusive Socratic classrooms are an imperative to bolster legal education’s structural foundation. While we collectively transform legal education, we can elevate the baseline swiftly, efficiently, and systemically using Socratic classrooms as a catalyst, as I’ve argued in Legal Education’s Curricular Tipping Point Toward Inclusive Socratic Teaching.

Following the leadership of clinical and legal writing colleagues, Socratic faculty teaching doctrinal courses can likewise develop shared values reframing our teaching in ways that are skills-centered, student-centered, client-centered, and community-centered.[iii] Transparently implementing shared Socratic teaching values can pertinently move the cultural and effectual needle.

Student-centered Socratic teaching is a vital component to inclusive and effective Socratic classrooms. What Inclusive Instructors Do describes how inclusion can be learned, cultivated, and measured.[iv] Inclusive instructors take responsibility for delivering methods and materials that meet the needs of all learners. They learn about their students and care for them. They continuously adapt to help students thrive and belong.[v]

The speed of a girl around town is about four kilometers per hour, or two and a half if she is wearing heels over six centimeters find a sex date in your area uk. The zone of possible contact is five meters, no more. So you're getting... How much are you getting? (Damn it, they told me to do my math properly, you'll need it!) Well, like, five seconds.

The annual Law School Survey of Student Engagement (LSSSE) is an important portal into examining the needs, challenges, and lived experiences of our students collectively, particularly as it reveals a changing climate. LSSSE’s 2021 Annual Report yields a critical call to action to support our students. It reveals how students are navigating heightened levels of “loneliness, depression, and anxiety.”[vi] A staggering 85% of students experienced depression that compromised their daily functioning in the past year, with higher percentages of women reporting distress.[vii]

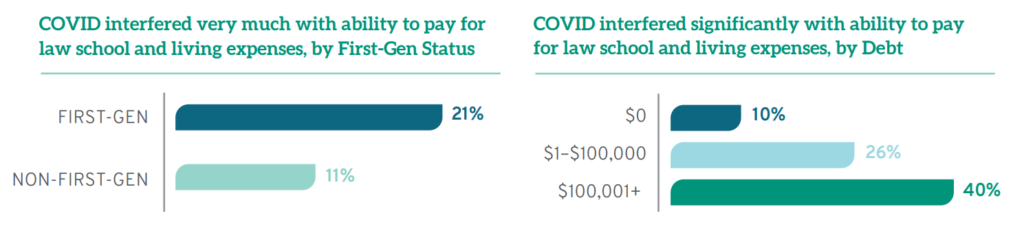

Amid COVID-19, our students have navigated our courses worried about food security, particularly Latinx, Black, and Asian American students.[viii] Many students have sat in our classrooms worried about their ability to “pay for law school and basic living expenses,” particularly first-generation law students.[ix]

Paolo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed reminds us that “trusting the people is the indispensable precondition for revolutionary change.”[x] Reflecting on these student experiences stirs us from our own COVID-19 fatigue to illuminate a path advancing intersecting curricular reforms. While no professor can alleviate the essential external challenges of our students, we can fortify the dominant Socratic classroom experience to minimize its abstract perspectivelessness. Socratic classrooms can be student-centered, skills-centered, client-centered, and community-centered, pivoting from professor-centered, power-centered, and anxiety-inducing. LSSSE’s analysis, reinforced by our direct student engagement, inspires us to reform Socratic classrooms with students, not simply for students. Sensitized to our student experiences liberates us to disrupt the status quo knowing that all students might benefit from greater connection, intentionality, and applicability in our Socratic classrooms.

Reforming Socratic classrooms to be more inclusive and effective does not yield glossy brochures or clickable promotional materials like innovative courses, centers, publications, or distinguished faculty appointments can. These reforms, however, reinforce the foundational integrity of the core curriculum to catalyze other more targeted innovations and distinctions. Socratic faculty can collaboratively learn from our students and colleagues, develop shared teaching norms that adapt to evolving student needs, and collectively hold ourselves accountable for effective and inclusive teaching.

[i] Meera E. Deo, Investigating Pandemic Effects on Legal Academia, 89 Fordham L. Rev. 2467 (2021); Meera E. Deo, Pandemic Pressures on Faculty, 170 Pa. L. Rev. Online – (2022), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4029052.

[ii] See e.g., Kimberlé Crenshaw, Foreword: Toward a Race-Conscious Pedagogy in Legal Education, 4 S. Cal. Rev. L. & Women’s Stud. 33, 34 (1994); Jamie R. Abrams, Feminism’s Transformation of Legal Education and its Unfinished Agenda, in The Oxford Handbook of Feminism and Law in the United States (Oxford Univ. Press, Eds. Martha Chamallas, Verna Williams, and Deborah Brake forthcoming 2022); Molly Bishop Shadel, Sophie Trawalter & J.H. Verkerke, Gender Differences in Law School Classroom Participation: The Key Role of Social Context, 108 Va. L. Rev. Online 30 (2022).

[iii] See Jamie R. Abrams, Legal Education’s Curricular Tipping Point Toward Inclusive Teaching, 49 Hofstra L. Rev. 897 (2021); Jamie R. Abrams, Reframing the Socratic Method, 64 J. Legal Educ. 562 (2015).

[iv] Tracie Marcella Addy, Derek Dube, Khadijah A. Mitchell & Mallory E. SoRell, What Inclusive Instructors Do 4 (2021).

[v] Id. at x (foreword).

[vi] Meera E. Deo, Jacquelyn Petzold, and Chad Christensen, The COVID Crisis in Legal Education, Law School Survey of Student Engagement Annual Report 5 (2021).

[vii] Id. at 12.

[viii] Id. at 5.

[ix] Id.

[x] Paolo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed 34 (1973).

Part 2: The COVID Crisis in Legal Education: Concern about Meeting Basic Needs

In our last post, we used LSSSE longitudinal data that was first reported in our 2021 Annuals Results, The COVID Crisis in Legal Education (pdf), to discuss the areas of law student engagement that were most impacted by the COVID-related challenges of the 2020-2021 academic year. In addition to the intangible losses, COVID also deepened ongoing disparities and inequities in legal education, as it did in society more generally. Student populations that were especially vulnerable pre-pandemic faced even greater challenges over the past year. The crisis has been perhaps most critical when considering basic necessities, though every level of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs has been affected—from the essentials of food, rest, physical safety, and financial security to the desire for belonging, appreciation, and ultimately achieving one’s full potential.

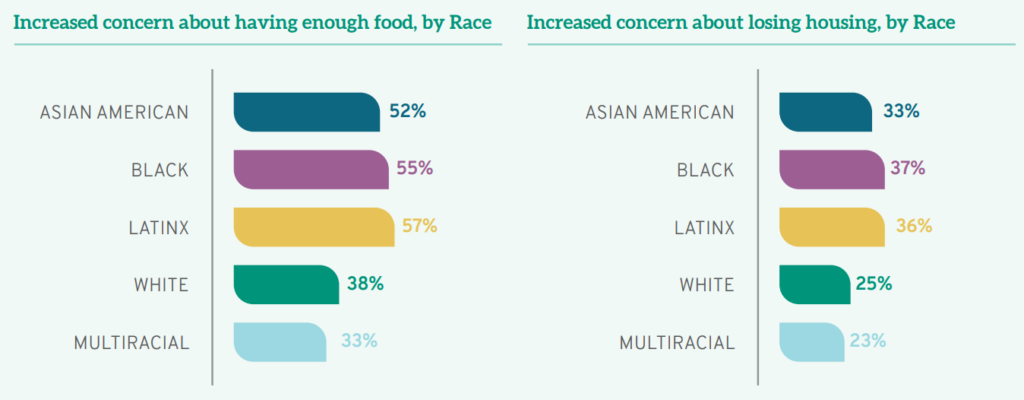

In 2021, many students struggled to meet their basic needs. In their responses to the LSSSE survey module Coping with COVID, 43% of all law students reported increased concern about having enough food due to COVID-19. This already troubling finding about students as a whole masks significant racial disparities with food insecurity: over half of all Black (55%), Latinx (57%), and Asian American (52%) students acknowledged that the past year brought increased concerns about whether they had enough food to eat.

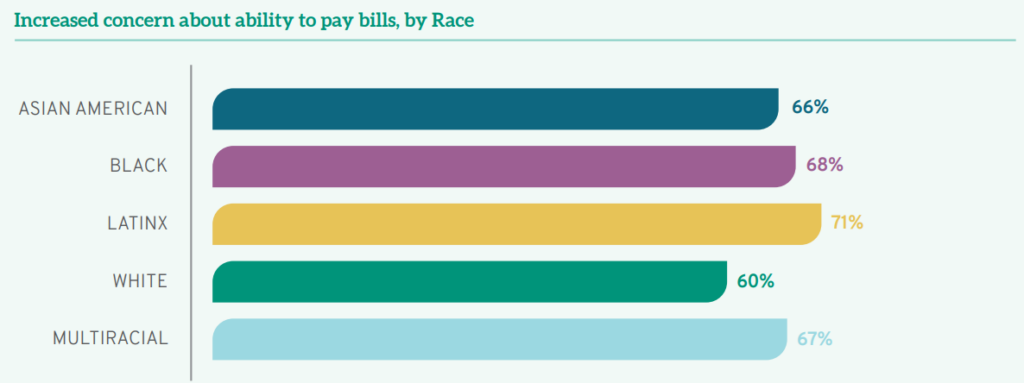

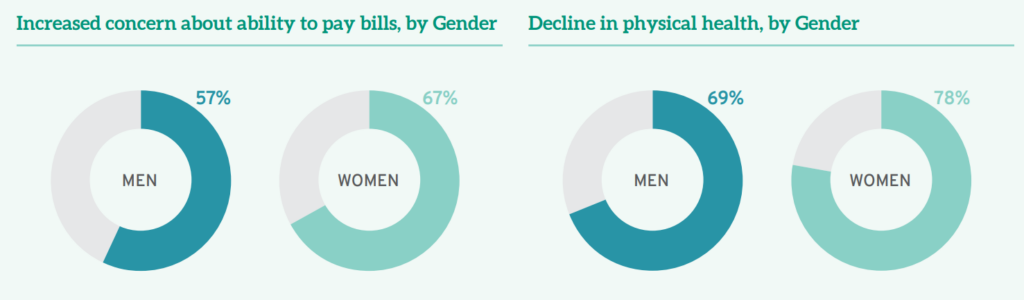

Financial concerns weighed heavily on students’ minds. Almost two-thirds (63%) of all student respondents had increased concerns about their ability to pay their bills, with both gender and race-based disparities increasing challenges for already vulnerable populations. For instance, among those who had elevated concerns about their financial security were 71% of Latinx students, 68% of Black students, 67% of multiracial students, and 64% of Asian Americans, compared to 60% of White students. Additionally, while over half of the men (57%) worried that the pandemic would affect their ability to pay their bills, over two-thirds of the women respondents (67%) faced similar financial uncertainty; a full 14% of women students reported that their financial fears had increased “very much,” compared to only 6% of men reporting that same high level of concern.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given elevated attention to satisfying basic needs like food, shelter, and financial security, as well as the realities of the pandemic, 75% of all law student respondents also reported increased concerns about their own health and safety, while 84% were also more worried about the health and safety of friends or family. A full 75% reported a decline in their own physical health over the past year, though men fared better in this regard: two-thirds (69%) of all men surveyed noted a decline in their physical health compared to over three-quarters (78%) of women law students.

Legal education has survived what were hopefully the deepest lows of the COVID-19 pandemic. But we did not emerge unscathed. The core of legal education continued as before—the basics of teaching and learning pivoted from in-person to online, professors successfully conveyed care and concern along with doctrinal analyses, and student satisfaction levels remained remarkably high. Yet just as in other aspects of our lives this past year, legal education lost much of its depth and flavor. It has been less fulfilling, less comprehensive, less effective at imparting the intangible skills our students will need to employ in their future careers. Most critically, the Coping with COVID Report (pdf) reveals that our students have been struggling beyond anything they have experienced collectively before.