A Long-Term Look at Relationships with Law School Faculty and Administrators, 2004-2023

In our last post, we examined how peer relationships between law students have changed over the last twenty years. Now we will consider the relationships between law students and their faculty and administrators over the same period.

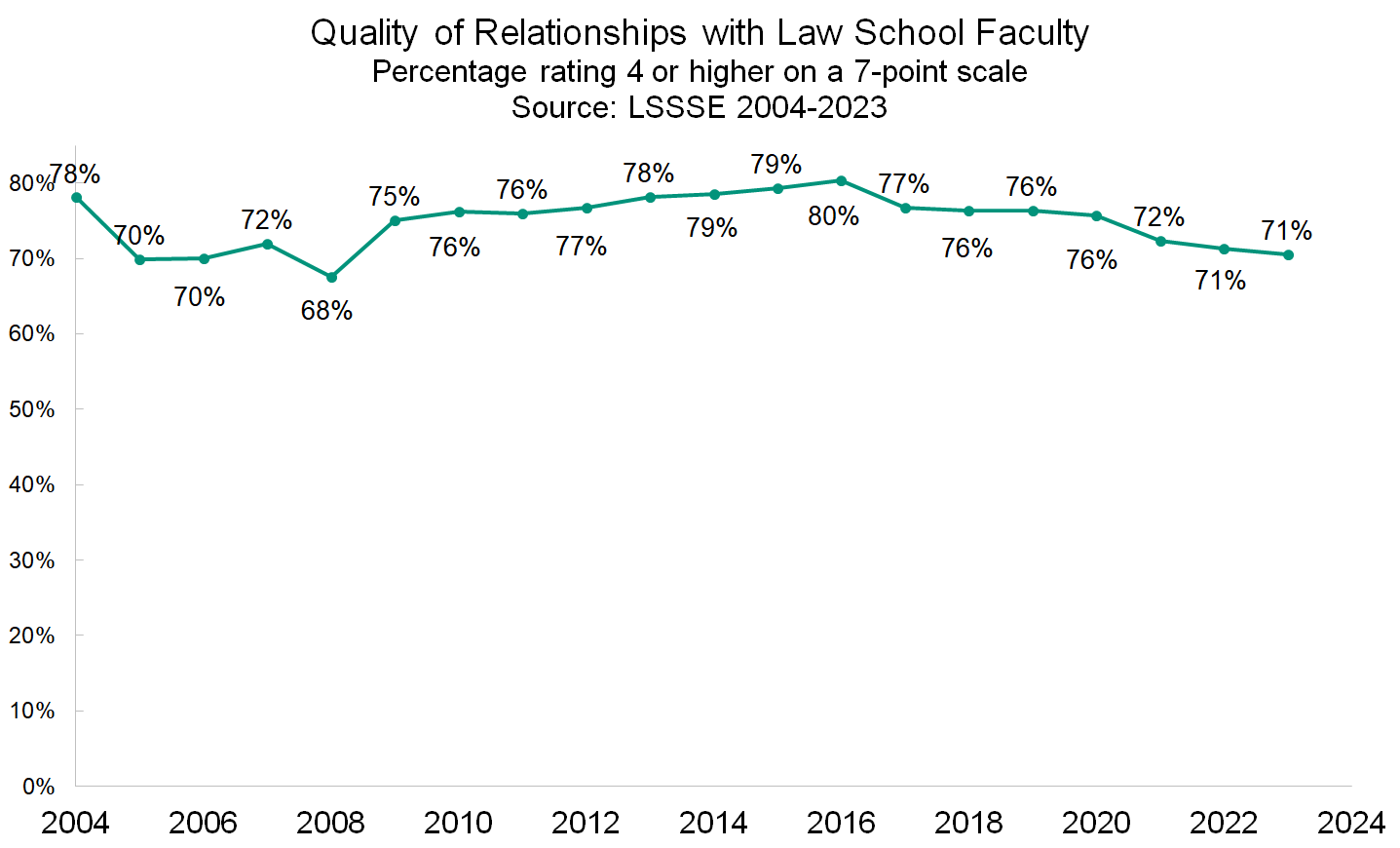

Generally, law students have better relationships with faculty than administrators. In 2023, 71% of law students were satisfied with their relationships with faculty (rated 5 or higher on a 7-point scale) compared to only 55% of students who were satisfied with their relationships with law school administrators.

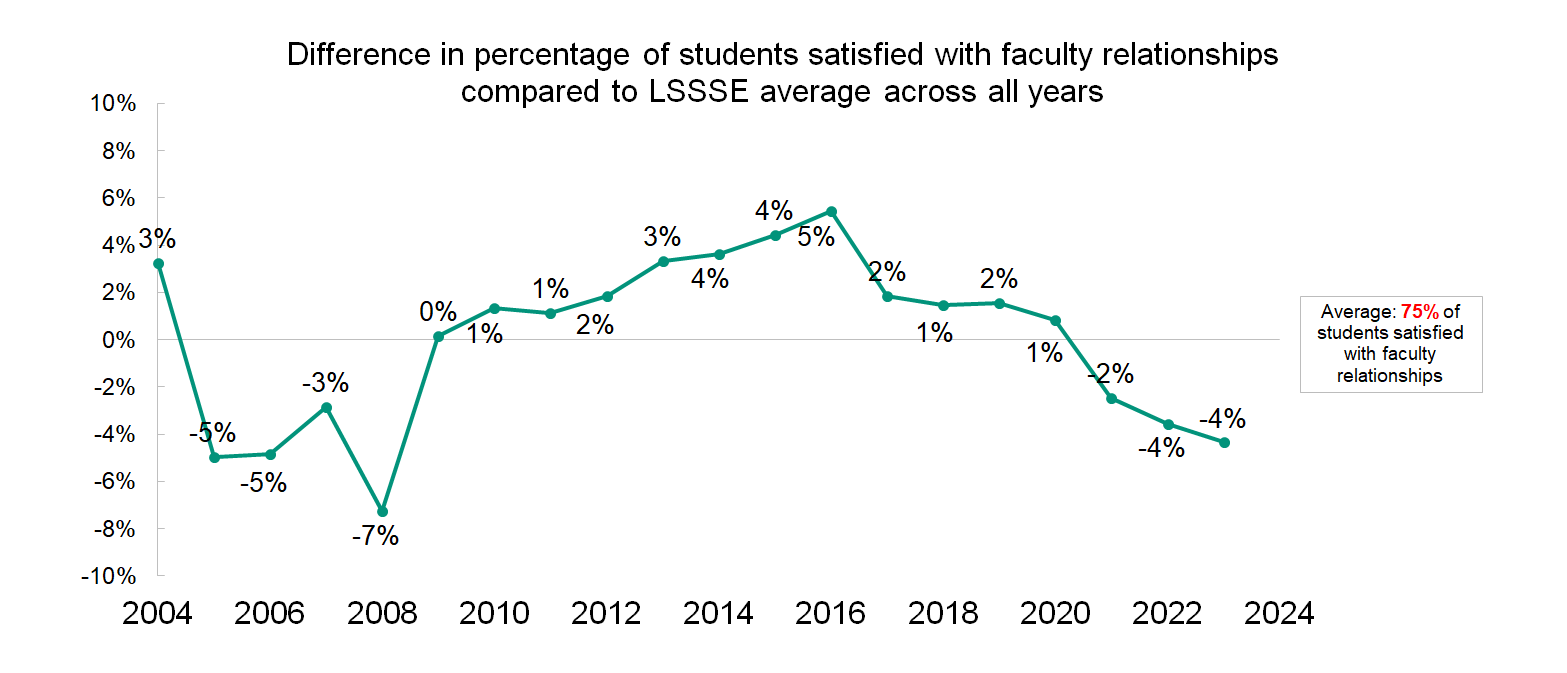

Much like satisfaction with peer relationships, satisfaction with faculty relationships has fluctuated over the last twenty years and may be a bit on the decline in recent years. Satisfaction with relationships with faculty hit an all-time high in 2016 at 80% but has been below the average of 75% since 2021.

This next graph gives us the ability to look specifically at the difference between satisfaction with faculty relationships and the all-time average (75%) for all years since the inaugural LSSSE survey in 2004.

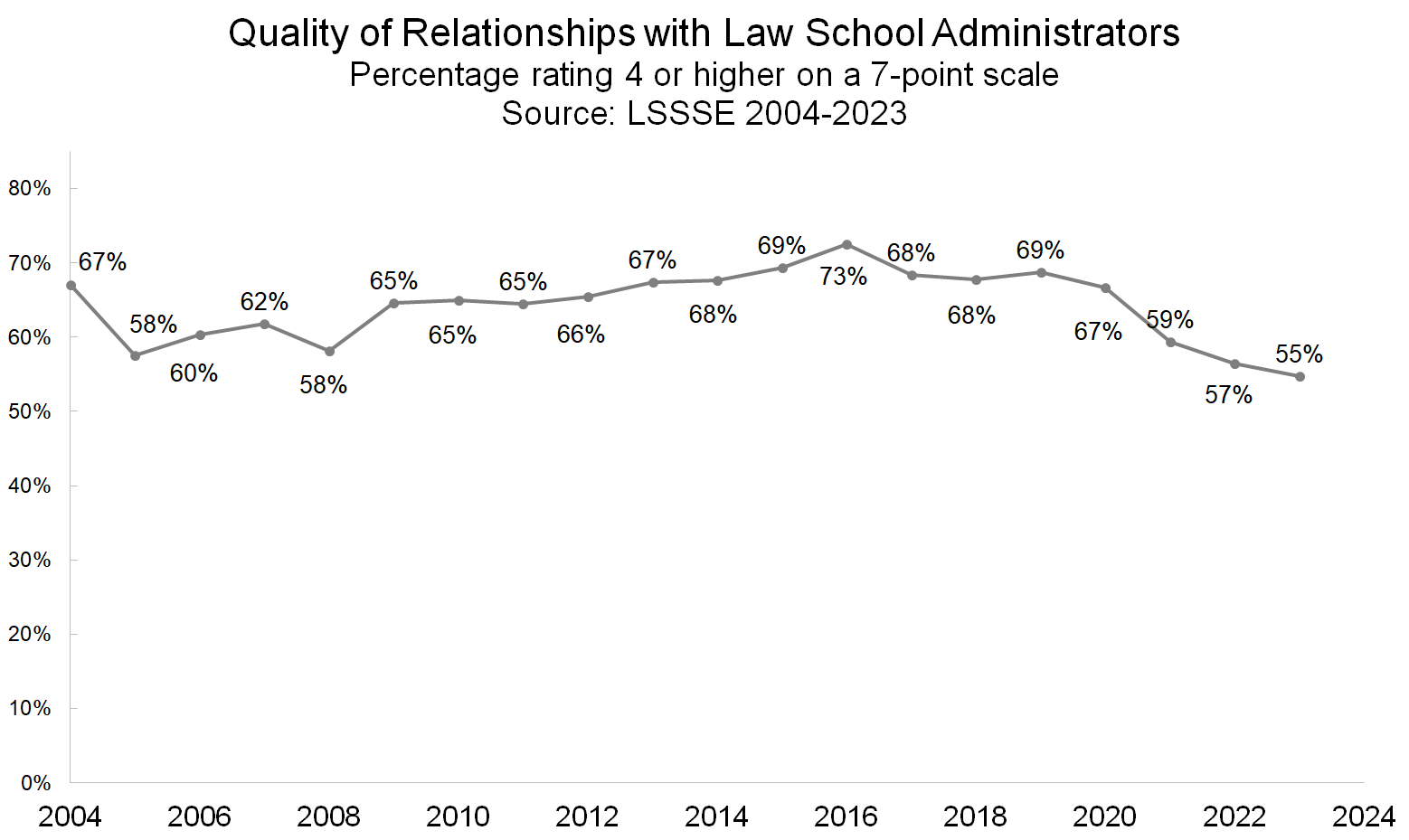

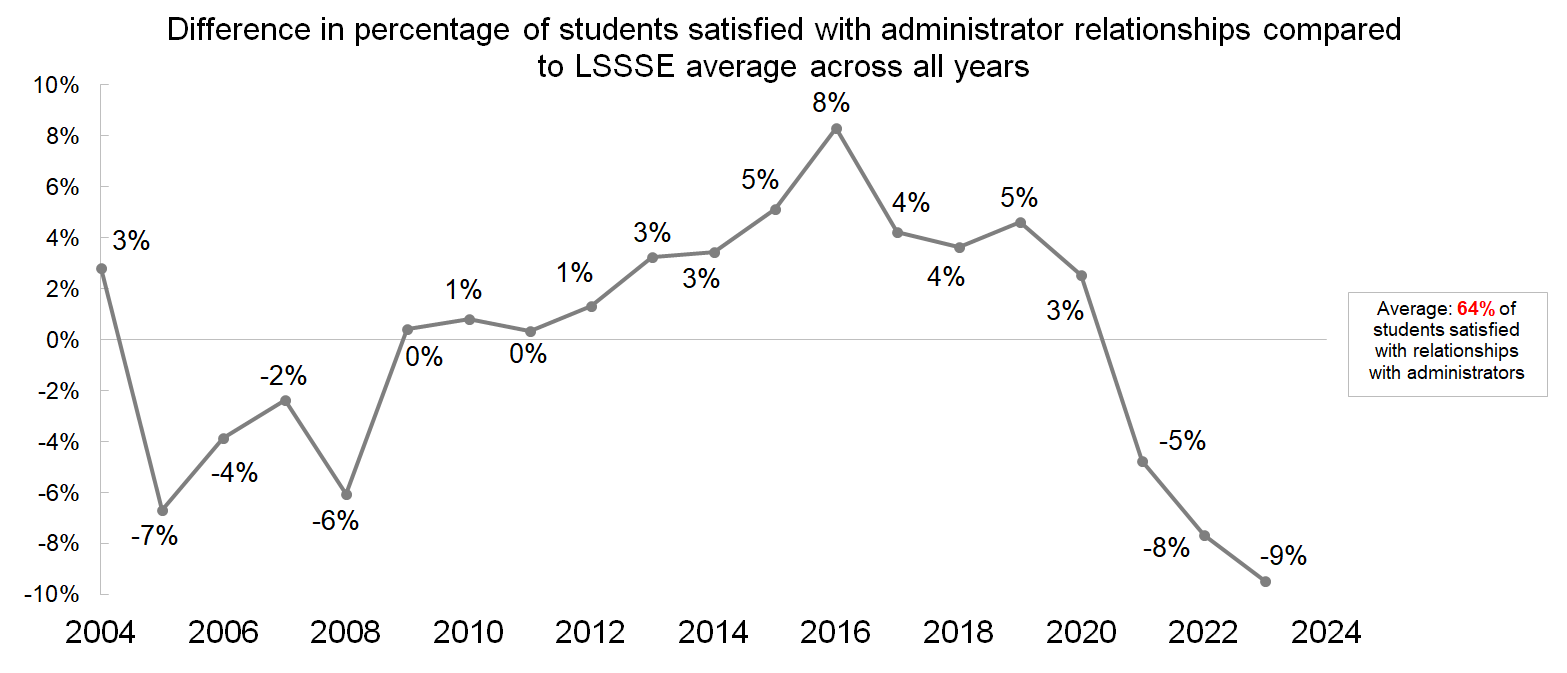

Students’ outlook on their relationships with administrators is even bleaker. The 2023 satisfaction rate of 55% is a full nine percentage points lower than the all-time average of 64%, and eighteen percentage points lower than the peak value of 73% in 2016. Although all law student relationships have been on a downward trajectory over the last few years, the relationships between students and administrators have been most strongly impacted and thus requires some special thought and attention by law schools. Perhaps the disruptions brought by COVID-19 have isolated students most severely from their administrators or perhaps the genesis of this discontent lies elsewhere.

Satisfaction with relationships with administrators has been on a precipitous decline since 2016.

It makes sense that students have stronger relationships with faculty since students see faculty on a regular basis and are likely to come to rely on faculty for academic guidance, feedback, and mentoring. Students and faculty are united in a common goal to study and understand the law, which can foster positive regard. Administrators, conversely, may be regarded as more impersonal given that their impact on the students' learning experience is more remote. Administrators may also be responsible for implementing rules and policies with which the students may not always agree. Hence, law students may understandably experience higher levels of rapport and satisfaction with their faculty than their administrators. However, given that law students’ relationships with administrators is currently at an all-time low, it may be worth some reflection to see how law school administrators came become more engaged to make a positive impact on the lives of their students.

A Long-Term Look at Relationships with Law School Peers, 2004-2023

A common misconception about law students is that their competition with each other for grades, jobs, and prestige creates a stressful and hostile law school environment. However, this is not the case for most law students who often find opportunities for support and friendship among their peers. Law students share common challenges and goals, and they can benefit from exchanging ideas and resources with each other. Many law schools also foster a culture of collegiality and mutual respect, where students are encouraged to help each other and celebrate each other's achievements. Rather than being a source of stress, peer relationships can be a source of resilience and well-being for law students. In fact, LSSSE data from 2023 show that only 38% of law students experienced quite a bit or very much stress or anxiety because of competition with peers. They are far more likely to be substantially stressed by academic performance (80% of students) and academic workload (79% of students).

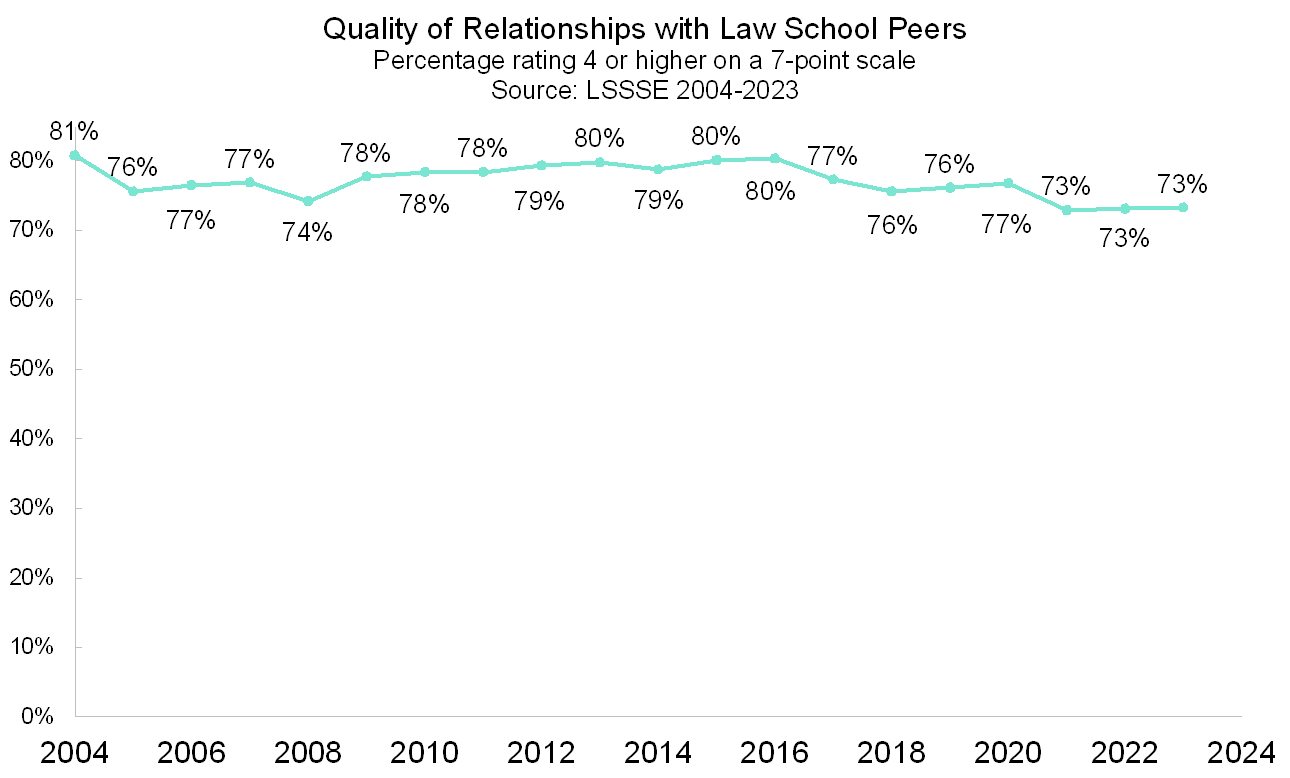

Since the 2004 LSSSE inaugural survey, an average of 77% of law students have said that their overall relationships with other students are mostly positive (at least a 4 on a 7-point scale). This number has fluctuated over time, with 81% of students having mostly positive relationships in 2004 and 73% of students feeling similarly in 2023.

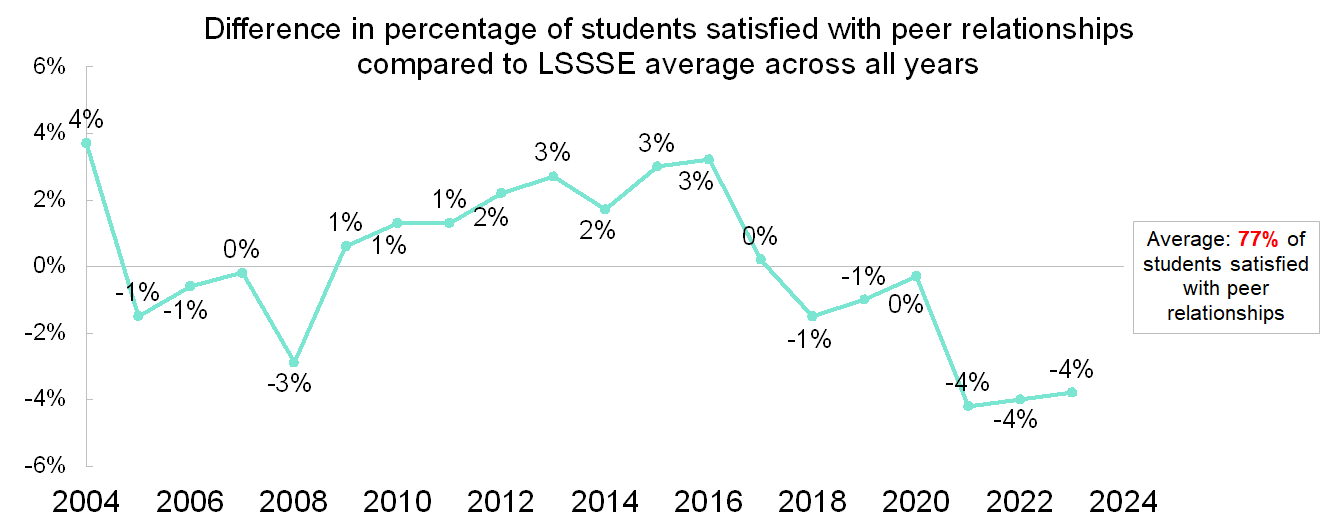

If we compare the percentage of students having an overall positive relationship with peers to the all-time LSSSE national average of 77%, we can see that the last several years have had slightly lower levels of peer satisfaction.

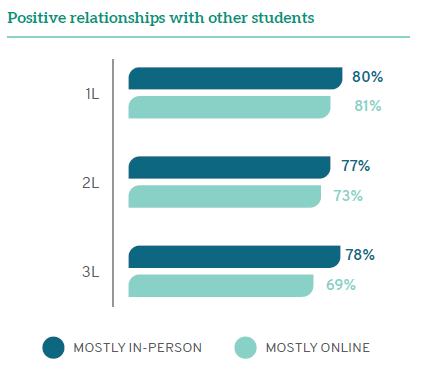

Although satisfaction with peer relationships was already on a somewhat downward trajectory before COVID-19, the notable decrease in relationship satisfaction during the 2020-2021 academic year may be largely driven by the decrease in relationship satisfaction among 1L students. In the spring of 2020 (largely before COVID-19 shutdowns started), 80% of 1L students were satisfied with their relationships with their fellow students. In the spring of 2021 after a year of huge disruptions in the law school environment including widespread online learning, only 72% of 1L students felt this way. However, 74% of 3L students were satisfied with their peer relationships in 2020 and again 74% of 3L students felt this way in 2021. Students who were introduced to law school in a time of necessary isolation were understandably somewhat less able to bond with their classmates. Orientation programs, study groups, moot courts, clinics, extracurriculars, and informal gatherings were either canceled, restricted, or moved online. These disruptions may have hindered the ability of 1L students to establish friendships and build rapport. Furthermore, online learning may have decreased the frequency and quality of interactions among students, as well as the sense of belonging and community that stems from being physically present in a shared space. Nevertheless, relationships among law students remained positive overall, showing that even the limitations of pandemic life did not prevent characteristically creative and resilient law students from forging relationships with each other. It will be interesting to examine how law students feel about their relationships with each other in future years now that life has largely returned to the pre-pandemic normal.

SPOTLIGHT ON: Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Law Students

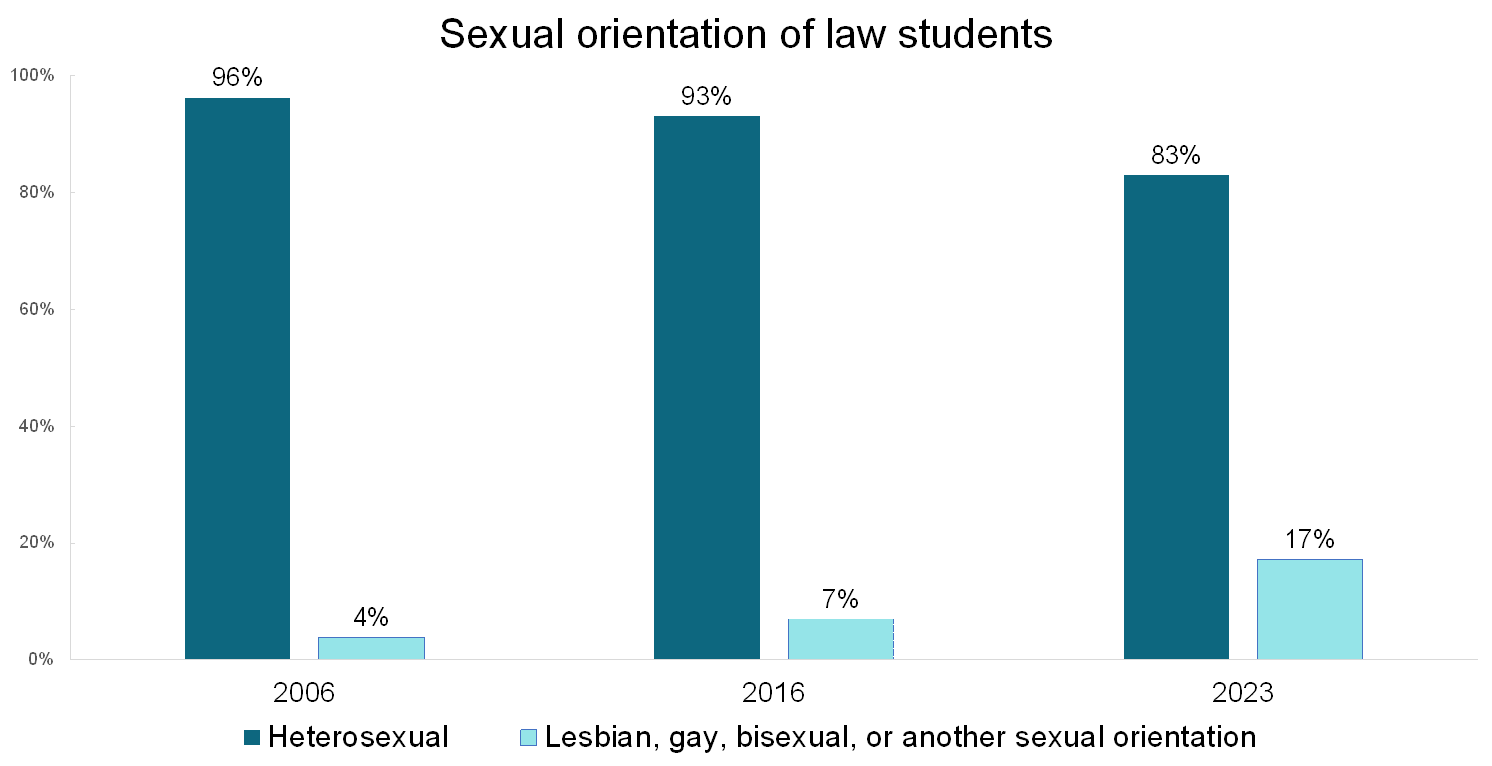

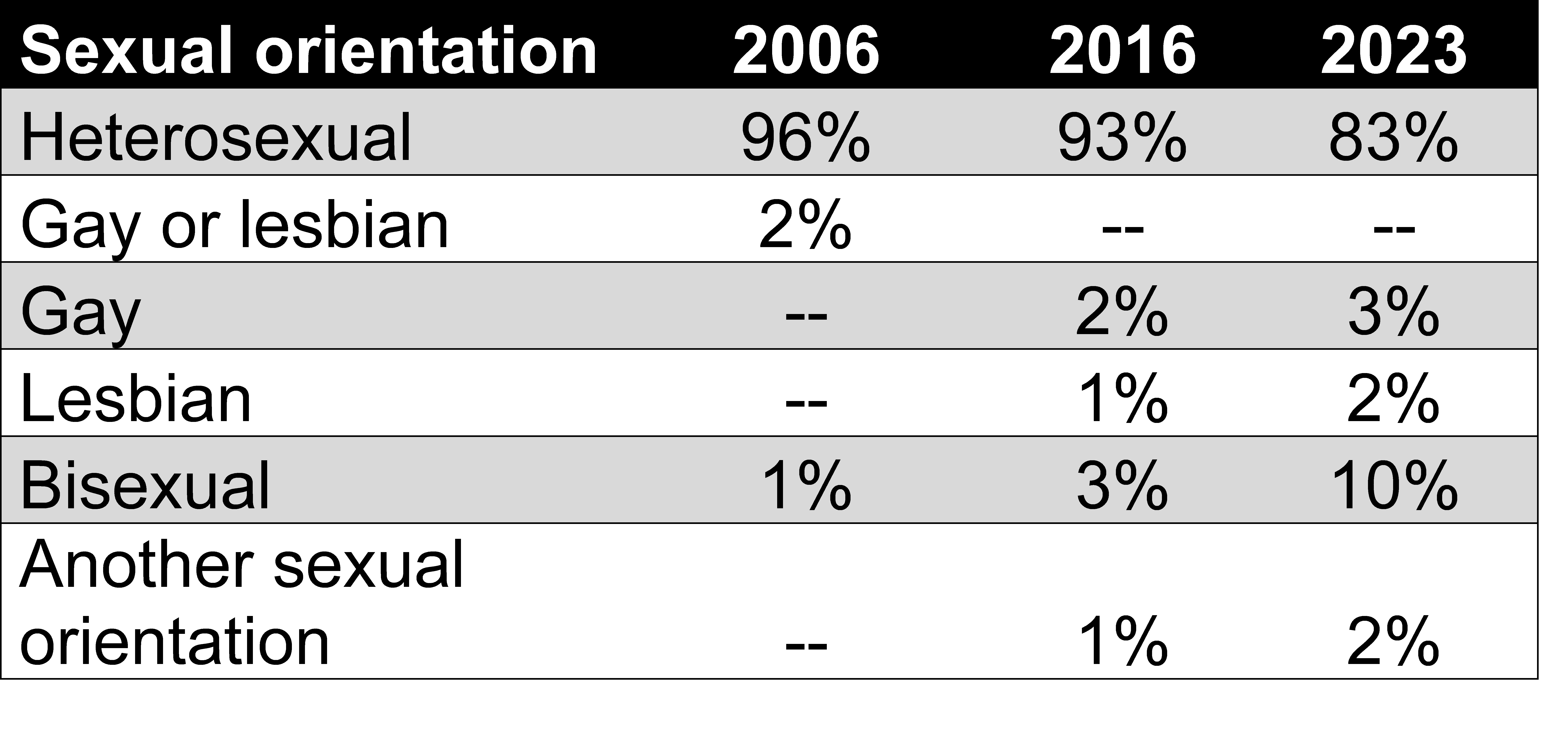

The percentage of law students who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or another non-heterosexual sexual orientation (LGB+) has grown dramatically over the last twenty years. When LSSSE first began asking about sexual orientation in 2006, 96% of law students identified as heterosexual, 2.5% were gay or lesbian, and only 1.3% were bisexual. The numbers had shifted noticeably by 2016, when the sexual orientation question was revamped slightly to be more inclusive. That year, 93% of law students were heterosexual, 2.3% were gay, 1.1% were lesbian, 2.6% were bisexual, and 0.9% were of another sexual orientation. However, by 2023, only 83% of law students identified as heterosexual. Three percent were gay, 1.7% were lesbian, 2% had another sexual orientation, and a full 10% identified as bisexual.

-- indicates response option was not available that year

-- indicates response option was not available that year

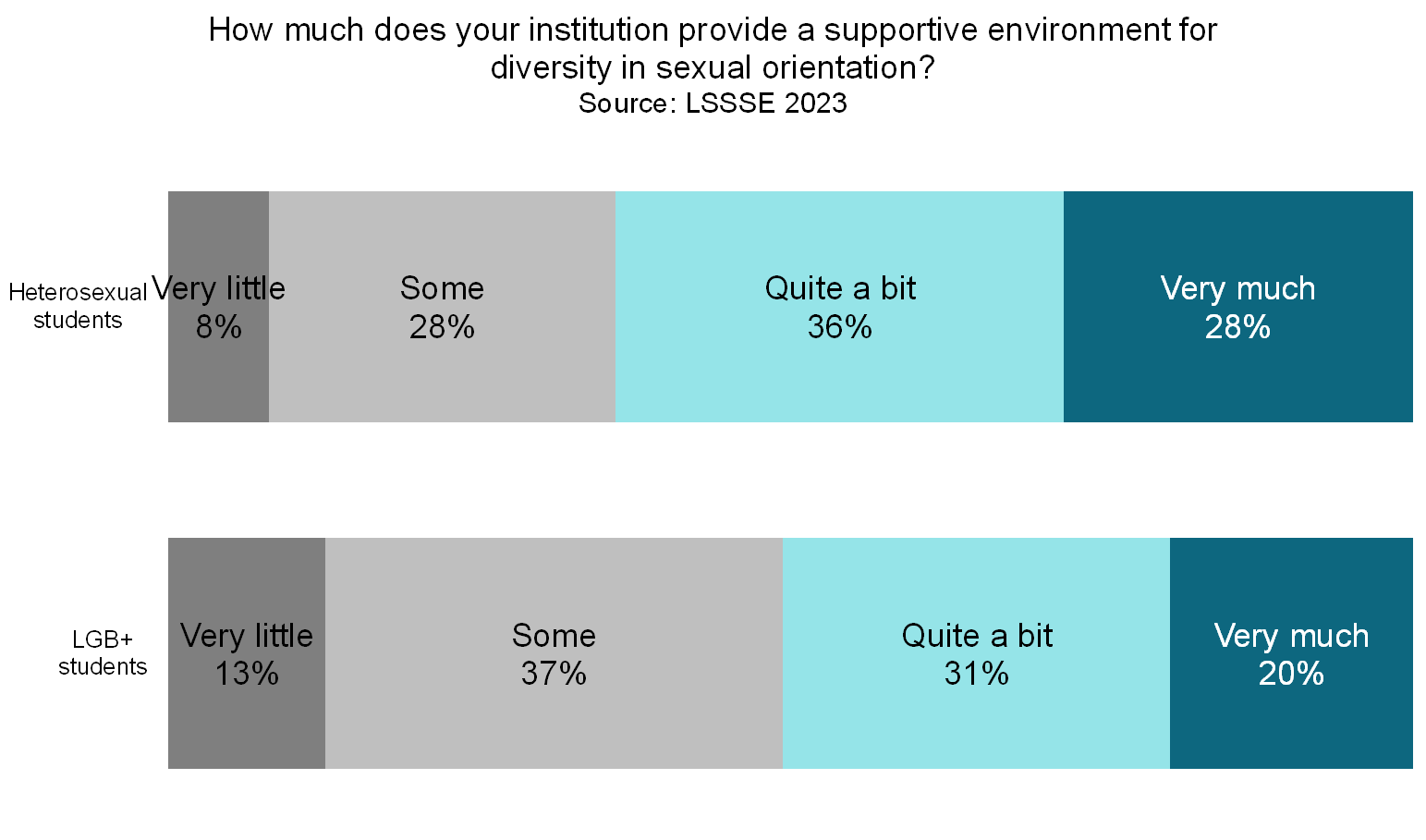

LGB+ students are somewhat less comfortable in law school relative to their heterosexual peers. For example, 72% of LGB+ students feel that they are part of the law school community compared to 77% of heterosexual students. Only half (50%) of LGB+ students believe that their law school places quite a bit or very much emphasis on ensuring that they are not stigmatized because of their identity (racial/ethnic, gender, religious, sexual orientation, etc.) compared to 61% of heterosexual students. Similarly, only about half (51%) of LGB+ students believe that their law school is a supportive environment for diversity in sexual orientation compared to just under two-thirds (64%) of heterosexual students.

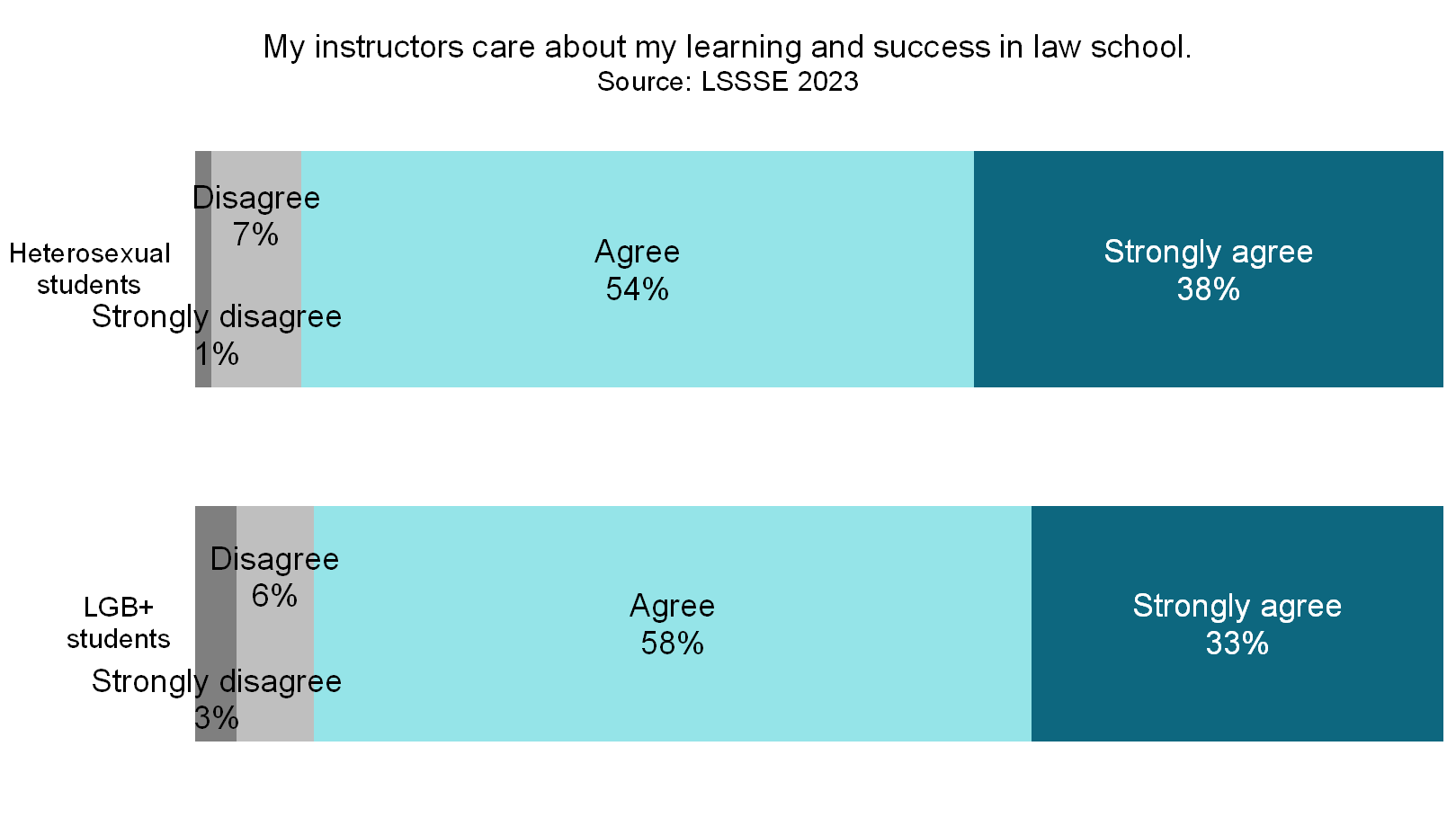

Despite the perception of a somewhat chilly climate overall, LGB+ law students are nearly equally likely as heterosexual law students to have strong relationships with law school faculty. LGB+ students rate their relationships with faculty on average 5.2 on a seven-point scale, compared to 5.3 for heterosexual students. A full 91% of LGB+ students believe their instructors care about their learning and success in law school, nearly equal to the 92% of heterosexual students who feel that way. Around four in five LGB+ and heterosexual students consider at least one instructor a mentor whom they feel comfortable asking for advice or guidance. Clearly, most students find help and support from their law school faculty, regardless of their sexual orientation.

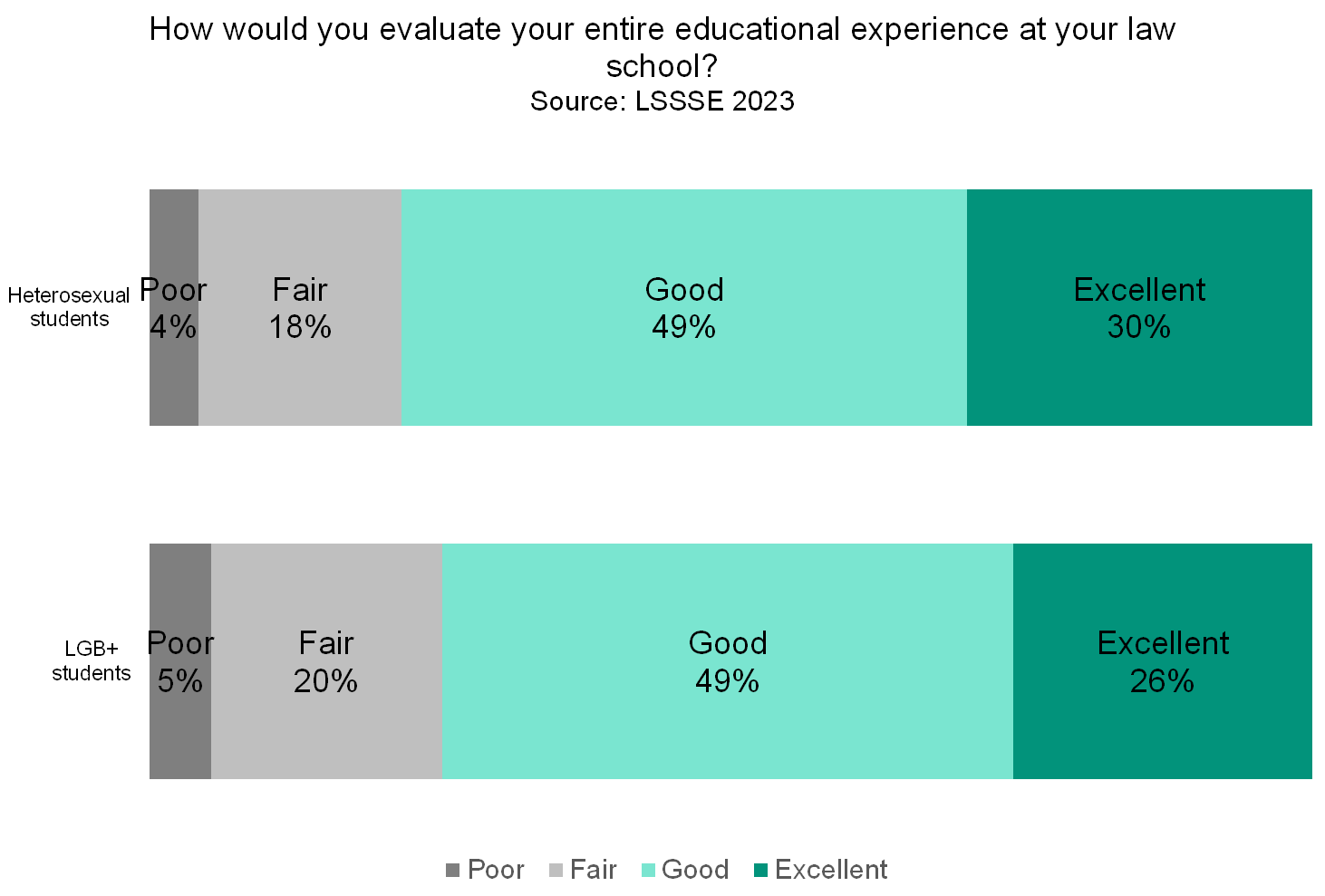

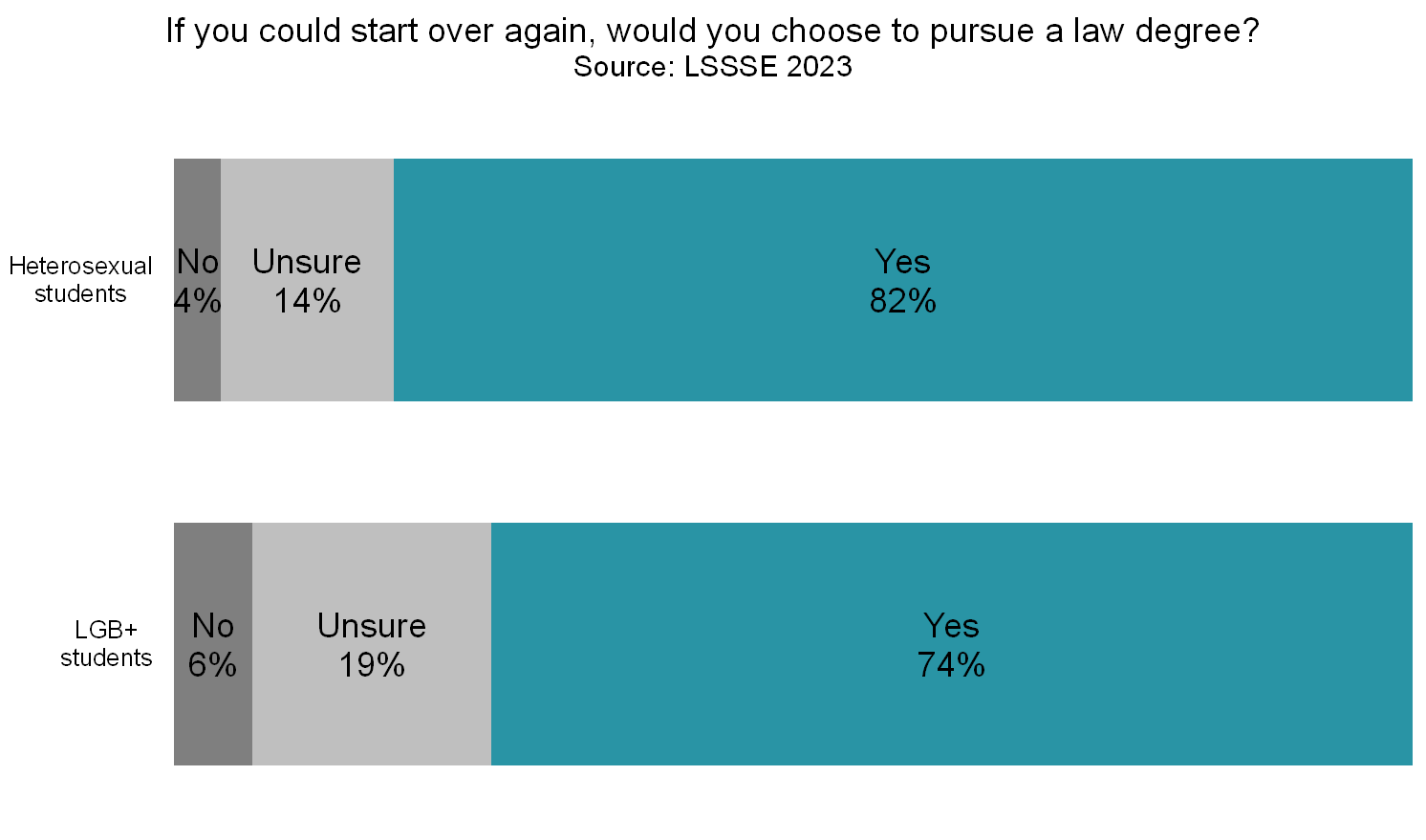

LGB+ students are somewhat less satisfied with their overall experience at law school compared to heterosexual law students. Three-quarters (75%) or LGB+ students rate their experience “good” or “excellent” compared to 78% of heterosexual students. However, LGB+ students are much less likely to be sure that they would pursue a law degree if they could start over. Just under three-quarters (74%) of LGB+ students said they would pursue a law degree and 19% were unsure. More than four in five (82%) heterosexual students would choose law school again and only 14% were unsure. Clearly, LGB+ law students are more likely than heterosexual law students to have regrets or misgivings about the path they selected.

Given that the population of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and other non-heterosexual students is growing rapidly in law schools, the concerns that these students have about the law school experience deserve particularly careful attention. LGB+ law students are less likely to feel that they belong, more likely to feel stigmatized, and more likely to question whether attending law school was the correct choice for them. Interestingly, most LGB+ students feel that their instructors care, and they are equally likely as heterosexual students to have an instructor that they consider a mentor. Perhaps law schools can use these personal connections to identify and address the concerns of their lesbian, gay, bisexual, and other non-heterosexual students in order to ensure equitable educational opportunities and a more supportive law school environment.

Success with Online Education: Relationships

The latest LSSSE Annual Results, Success with Online Education (pdf), focuses on the largely positive online learning experiment that law schools embarked upon due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This week and next week we will share selected snippets from the results. In this post we will describe how the switch to online learning impacted relationships among law students, law faculty, and administrators.

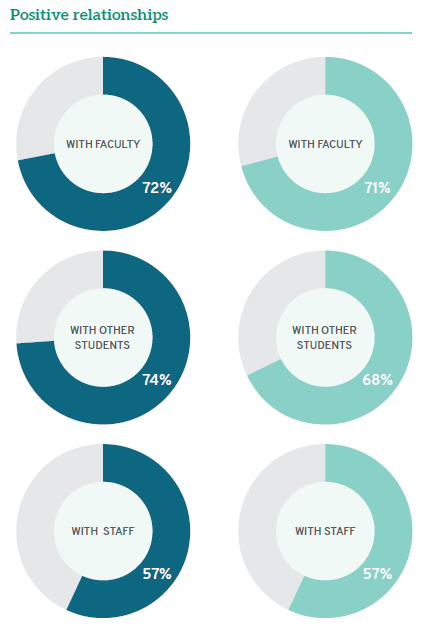

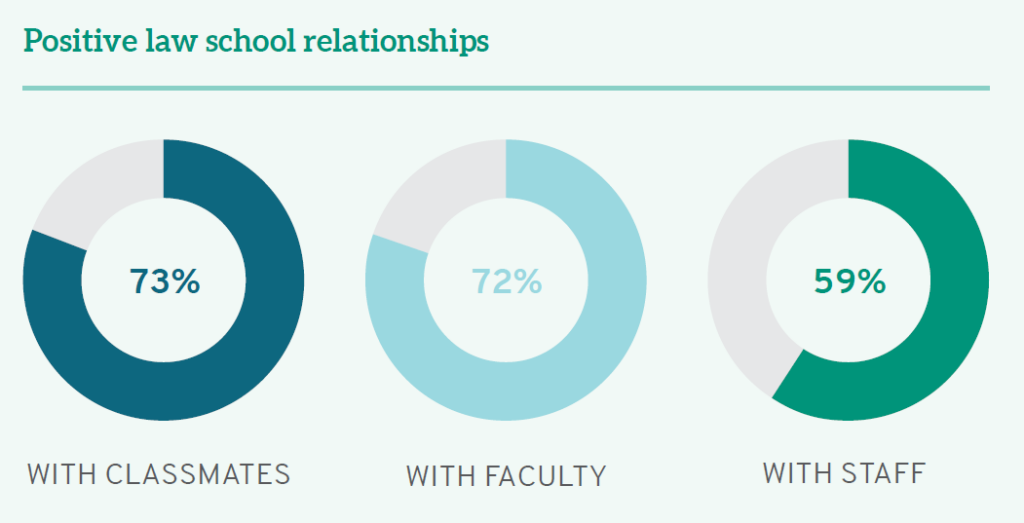

LSSSE data confirm other research showing how law school faculty have invested an enormous amount of energy and effort to connect with students, regardless of instructional modality. A full 72% of students taking mostly in-person classes have strong relationships with faculty (5 or higher on a 7-point scale), and 71% of mostly online students feel the same way. Students remain highly engaged with faculty in an online environment.

Online students and in-person students are equally likely to have positive relationships with administrative staff. A little over half (57%) of each group rate their relationships with their law school’s administrators a 5 or higher on a 7-point scale. Career services-oriented staff could consider using these relationships to bring more targeted career guidance to online students to narrow the gap in career preparedness between online students and in-person students. However, the relatively low percentage of both in-person and online students who have strong relationships with staff is a point of concern that should be addressed to better support law student development.

Despite similarly positive relationships with professors, students in mostly online classes are less likely than others to have strong relationships with each other. Only 68% of online students rate their relationships with their classmates positively, compared to nearly three-quarters (74%) of in-person students. There is again a disparity across class years, with 1Ls having similarly positive peer relationships regardless of mode of attendance and online 3Ls being much less likely to enjoy strong relationships with their peers than 3Ls attending in person. There may be a loss of social connections among online students because of a lack of the sort of incidental contact that builds relationships over time.

Next week we will discuss the learning experience in the virtual classroom. For the complete story, you can view the entire report on our website.

Relationships with Law Faculty

Law students generally have strong relationships with law school faculty members. In 2022, 71% of LSSSE respondents ranked their relationships with faculty a 5 or higher on a 7-point scale, where 7 represents faculty who are “available, helpful, and sympathetic.” Only 12% of students ranked their relationships a 3 or lower, and a mere 1% of students ranked their relationships a 1, meaning they feel that the faculty at their law school are “unavailable, unhelpful, and unsympathetic.”

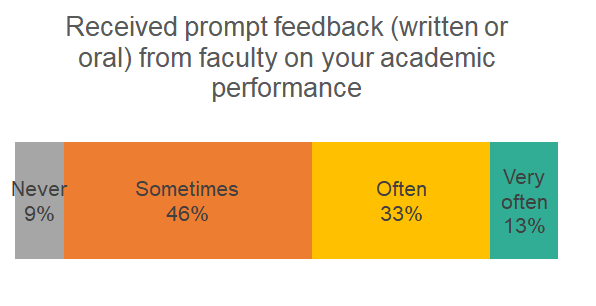

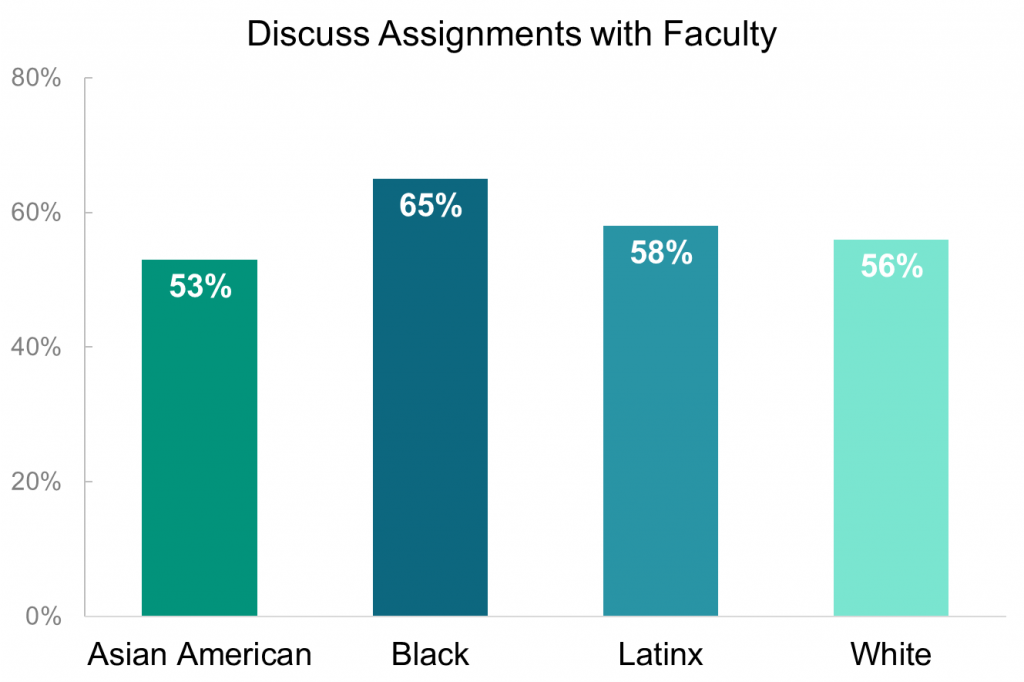

Relationships with instructors are built both inside and outside the classroom. More than half (53%) of law students discussed assignments with a faculty member often or very often, and only 5% never discussed assignments with a faculty member. After completing assignments, most law students (91%) receive prompt feedback from faculty on their academic performance at least sometimes. However, only 13% say they receive prompt feedback very often, and 9% never receive prompt feedback.

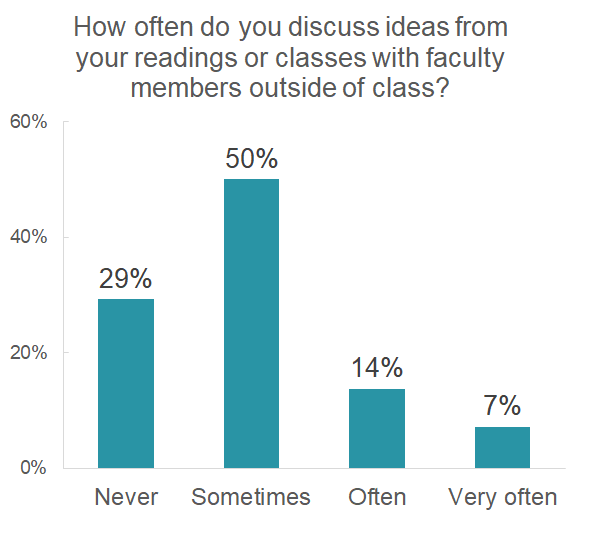

About one in five students (21%) often or very often discussed ideas from their readings or classes with faculty members outside of class, and another half (50%) did so sometimes. This practice tapers off a bit over time, with 22% of first-year students discussing ideas with faculty members outside of class often or very often compared to 19% of 3Ls and 11% of 4Ls.

Law school faculty can provide crucial guidance about navigating the legal job market, and the vast majority of students (84%) take advantage of their advice. Just over a third of students (36%) discuss their career plans or job search activities with a faculty member of advisor often or very often. Around 82% of first-generation students (neither parent holds a bachelor’s degree) have discussed their career plans with faculty compared to 85% of their non-first-generation peers.

The relationships students form during their time in law school can be crucial to their future success. The majority of law students make the most of these relationships, and they appreciate the support and knowledge they receive from the faculty of their law schools.

Part 1: The COVID Crisis in Legal Education: Impact on Core Mission and Enriching Experiences

Because LSSSE has been annually administered since 2004, the survey was well-positioned to capture shifts in students’ perceptions and behaviors during the uniquely challenging 2020-2021 academic year. Our 2021 Annual Results, The COVID Crisis in Legal Education (pdf) draws from the core survey and two new modules (“Coping with COVID” and “Experiences with Online Learning”) to identify key struggles and successes of legal education during a period marked by uncertainty and disruption.

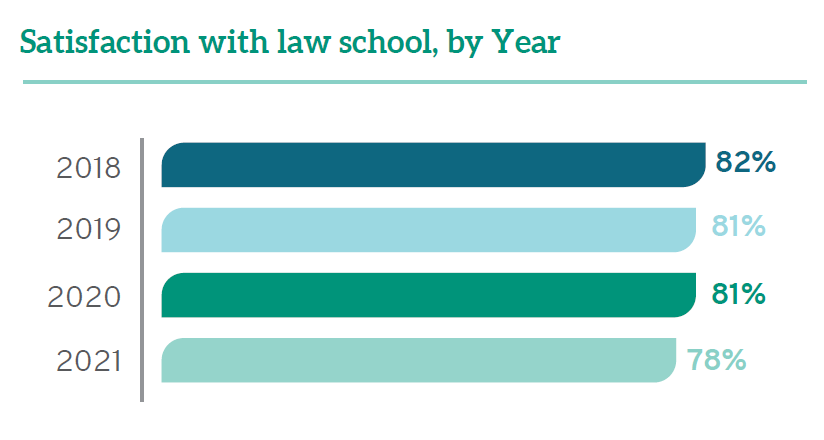

In the midst of a challenging year, some positives emerge from the data. Overall satisfaction remained high throughout legal education and comparable to past years. A full 78% of students in 2021 rated their entire educational experience in law school as “good” or “excellent,” which is similar to rates from recent years (82% in 2018, and 81% in 2019 and 2020). This is a testament to the significant efforts of faculty, staff, and administrators who pivoted to meet student needs as well as to the resiliency of the students themselves.

Nevertheless, the ability to forge and foster relationships has been especially difficult during the pandemic, which is borne out in the data. The percentage of students reporting positive relationships with staff dropped from 68% in 2018 to 59% in 2021—the lowest percentage recorded since LSSSE began collecting data on student-staff interactions in 2004. During those same years, positive student relationships with faculty and fellow students dropped just slightly from 76% to 72% and 76% to 73%, respectively. A full 93% of students appreciated that their law professors showed “care and concern for students” as the pandemic raged around them. First-year students were less likely to report positive relationships than 2Ls and 3Ls—likely because upper-class students could build on foundations they had cemented pre-COVID while 1Ls were attempting to start relationships from scratch in the midst of the pandemic.

The core of legal education remains relatively unchanged. Every year from 2018 to 2021, 85% of students have acknowledged that their schools contributed “quite a bit” or “very much” to their ability to acquire a broad legal education. There were also minimal changes this year compared to years past with regard to students developing legal research skills (80- 83%) and learning effectively on their own (81-82%).

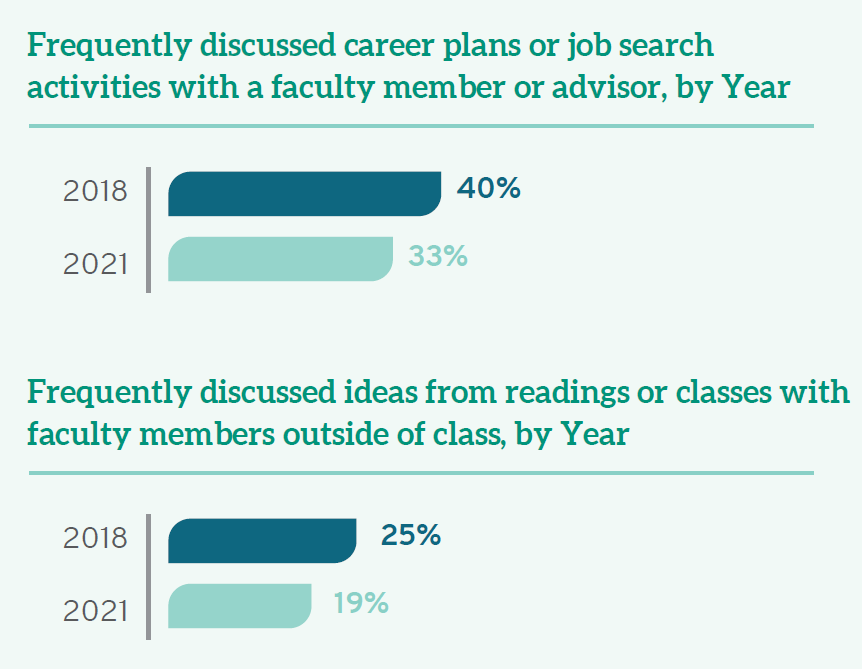

Yet the intangibles of legal education were significantly affected by COVID-19, with potential negative consequences on the professional competency of these future lawyers. A full 90% of students noted that COVID interfered with their ability to participate in special learning opportunities, including study abroad, internships, and other field placements. While discussions about course assignments and faculty feedback on academic performance remained constant, just one-third (33%) of all law students found frequent occasions to talk with faculty members or other advisors about career plans or the job search process (down from 40% in 2018), and only 19% frequently discussed ideas from readings or classes with faculty members outside of class (down from 25% in 2018). There were also fewer opportunities for students to work with faculty members on activities other than coursework.

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted nearly all aspects of life, and law school is no exception. Although law schools did their best to continue on with the education of the next generation of lawyers, there were still marked decreases in student engagement, particularly in building relationships and gaining experience outside the classroom. In our next post, we will explore the areas in which law students struggled the most in their lives and show how the pandemic disproportionately impacted those students who were already the most vulnerable.

Where do students get advice?

LSSSE’s optional Student Services module asks students about whether and how often they access academic and career services. Students draw from various sources to get advice about law school, legal education, and their future careers. Here, we look at the most commonly selected meaningful sources of advice for students and examine how patterns of advice-seeking change as students progress through law school.

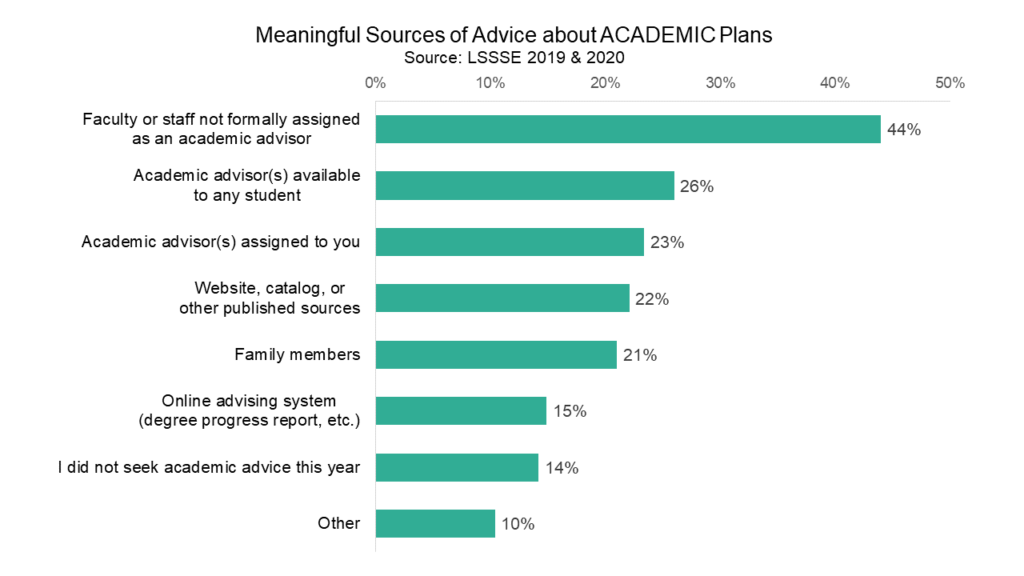

Advice about Academic Plans

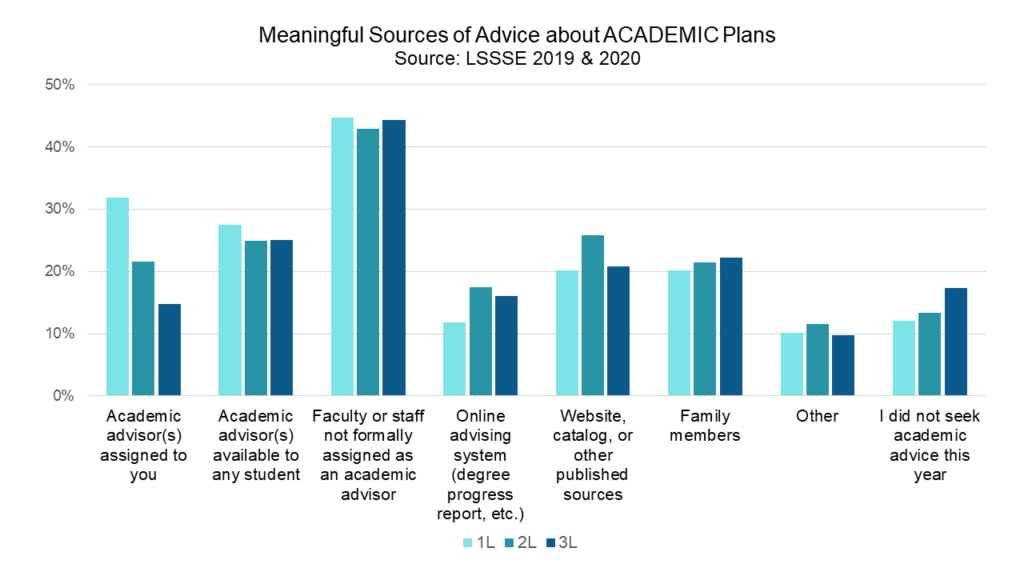

Faculty or staff not formally assigned as an academic advisor are the most common meaningful source of advice about academic planning. Over 40% of LSSSE respondents rely on these personal relationships that they develop with the law school professionals around them. Formal academic advisors –those assigned and those available to any students – are the second and third most commonly used sources of advice and were selected by 26% and 23% of students, respectively. About 22% of students consider websites, catalogs, or other published sources to be meaningful sources of advice about academic plans, and roughly one in five consulted family members. Only 14% of respondents did not seek academic advice from anyone during the current school year.

Students appear to rely less on assigned academic advisors as they progress through law school. Roughly one-third of 1L students say their assigned academic advisor was a meaningful source of advice, but only 15% of 3L students feel the same way. Perhaps unsurprisingly, 3L students were slightly less likely to seek academic advice than 1L and 2L students.

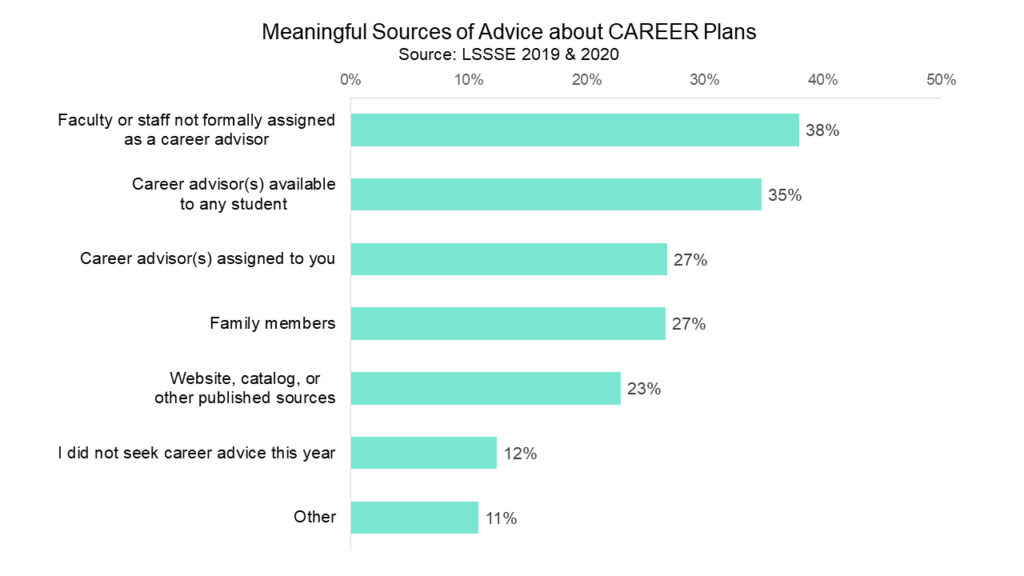

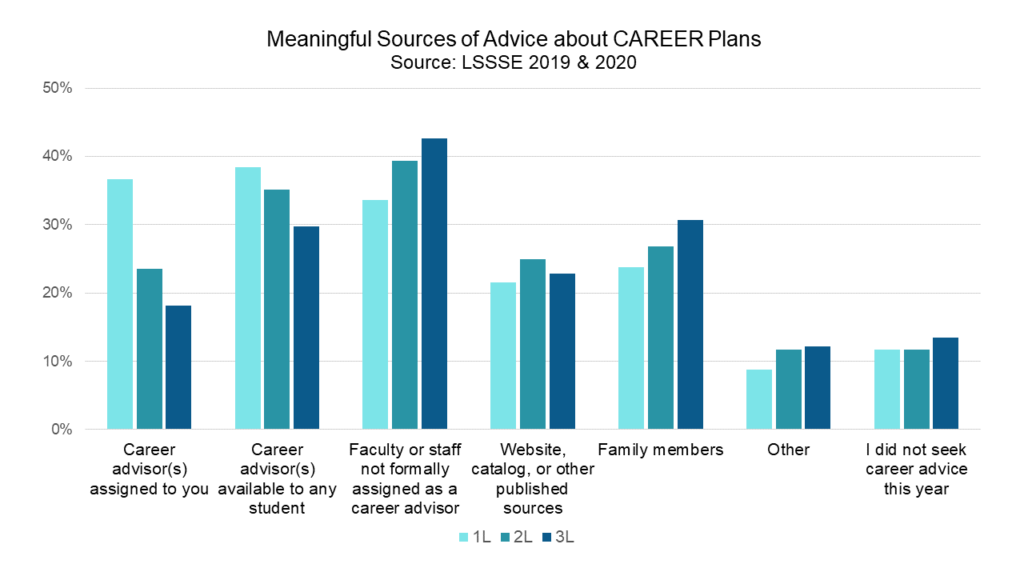

Advice about Career Plans

The ranking of meaningful sources of advice about career planning is remarkably similar to the ranking for advice about academic planning. Students highly value their relationships with law school faculty and staff when it comes to seeking career advice, ranking faculty or staff not formally assigned as a career advisor highest (38%), followed by career advisors available to any student (35%) and then assigned career advisors (27%). Interestingly, students were equally likely to select family members and assigned career advisors as meaningful sources of career advice. Twelve percent of respondents did not seek any career advice during the current school year.

Students rely less on assigned career advisors as they progress through law school, which is similar to the pattern we saw for academic advising. However, the gradual decrease in reliance on formal career advising is somewhat mirrored by a gradual increase in reliance on advice from faculty or staff not formally assigned as career advisors. It would appear that as students refine their interests and form relationships with particular faculty or staff members, they start to rely more on personal relationships for career advising and less on relationships facilitated by the structure of law school.

Annual Results 2018: Relationships Matter – Student Relationships

Decades of research on student engagement and student learning demonstrate the importance of peer interactions. Engaging with classmates in meaningful ways contributes to a deeper sense of belonging and enhances understanding of classwork, leading to better academic and professional outcomes (Hurtado & Carter, 1997; Pascarella & Terenzini, 2005; NSSE, 2013).

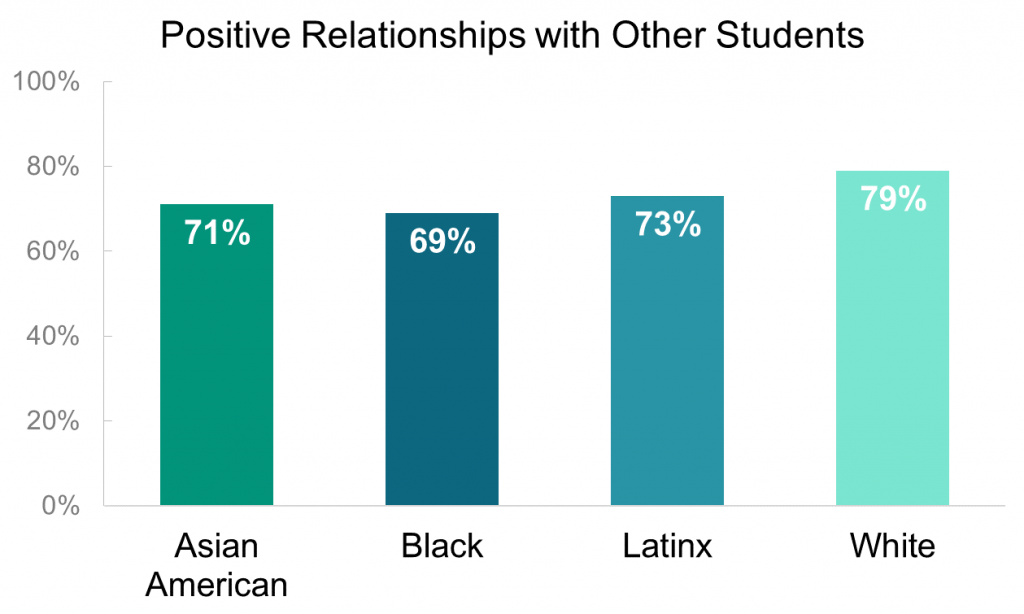

Although law school is an inherently stressful and anxiety-producing endeavor, the vast majority of students (76%) report that their peers are friendly, supportive, and contribute to a sense of belonging. There are noticeable variations by race/ethnicity. White students are most likely to report positive relationships with peers (79%), as compared to Black (69%), Asian American (71%), and Latinx (73%) students.

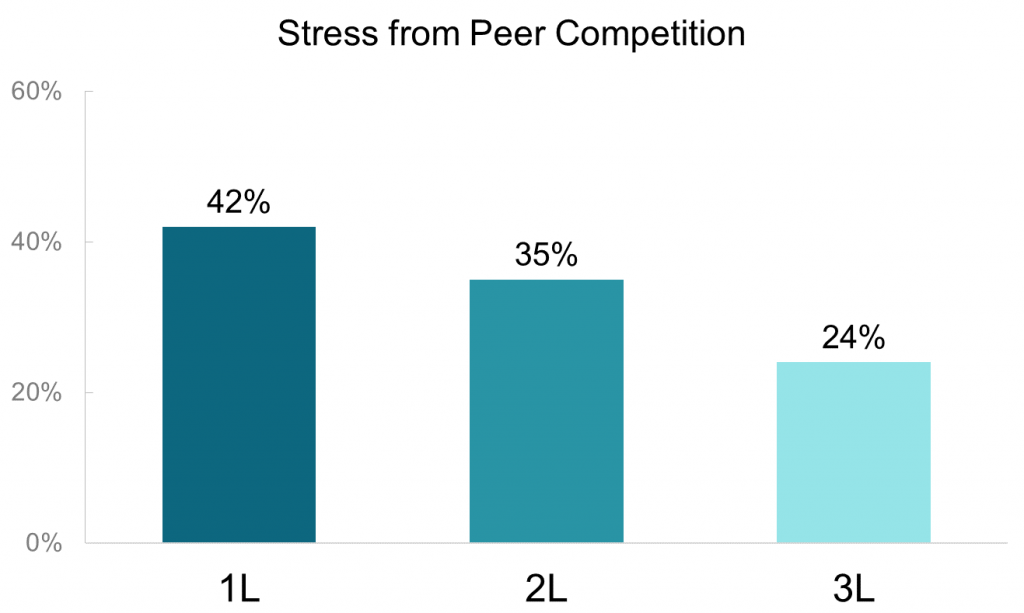

The Student Stress Module examines law student stress and anxiety—their sources, impact, and perceptions of support offered by law schools to manage stress and anxiety. One question asks directly about various sources of stress and anxiety that students may face in school. High percentages of students report that academic performance (77%) and academic workload (76%) produce stress or anxiety, but competition amongst peers does not create or magnify these feelings for most students. Students report that competition amongst peers is most significant during the first year of law school but sharply declines each year. Forty-two percent of 1L students report that peer competition is a source of stress or anxiety. By the third year of law school that number drops to 24%.

Annual Results 2018: Relationships Matter – Advising

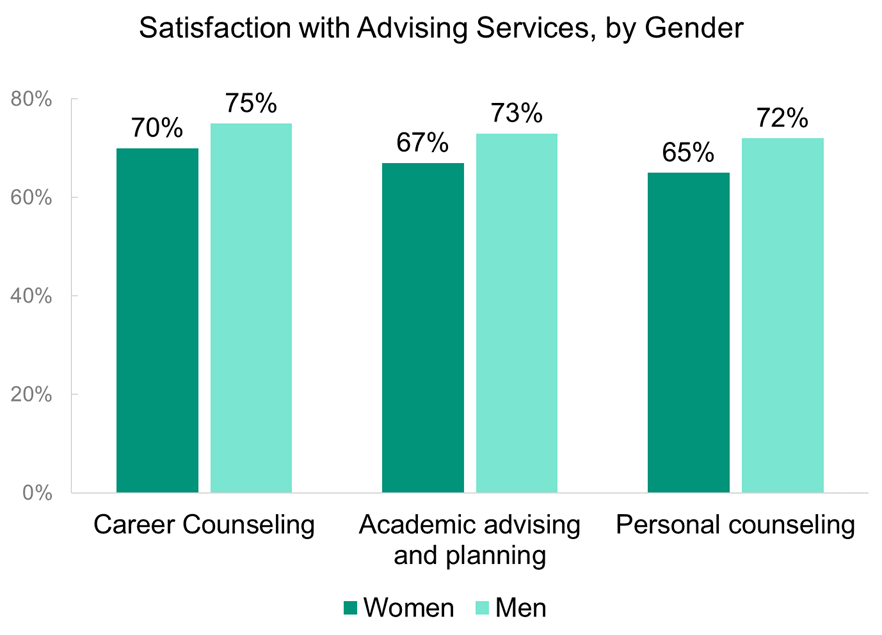

A majority of students are pleased with the quality of advising and their relationships with administrators:

- 69% are satisfied with academic advising and planning.

- 66% are satisfied with career counseling.

- 64% are satisfied with job search help.

- 70% are satisfied with financial aid advising.

- 68% report that administrative staff are helpful, friendly, and considerate.

The quality of relationships with advisors and administrators is both positive and relatively consistent across race, gender, and year in school. Seventy percent of 1L students (and 67% of 2Ls and 3Ls) report that administrative staff are helpful, considerate, and flexible. Seventy-nine percent (79%) of students consider at least one administrator or staff member as someone they could approach for advice or guidance on managing the law school experience. Higher percentages of Black students (87%) rely on these relationships than students from other racial backgrounds (79% for Asian American, white, and Latinx students).

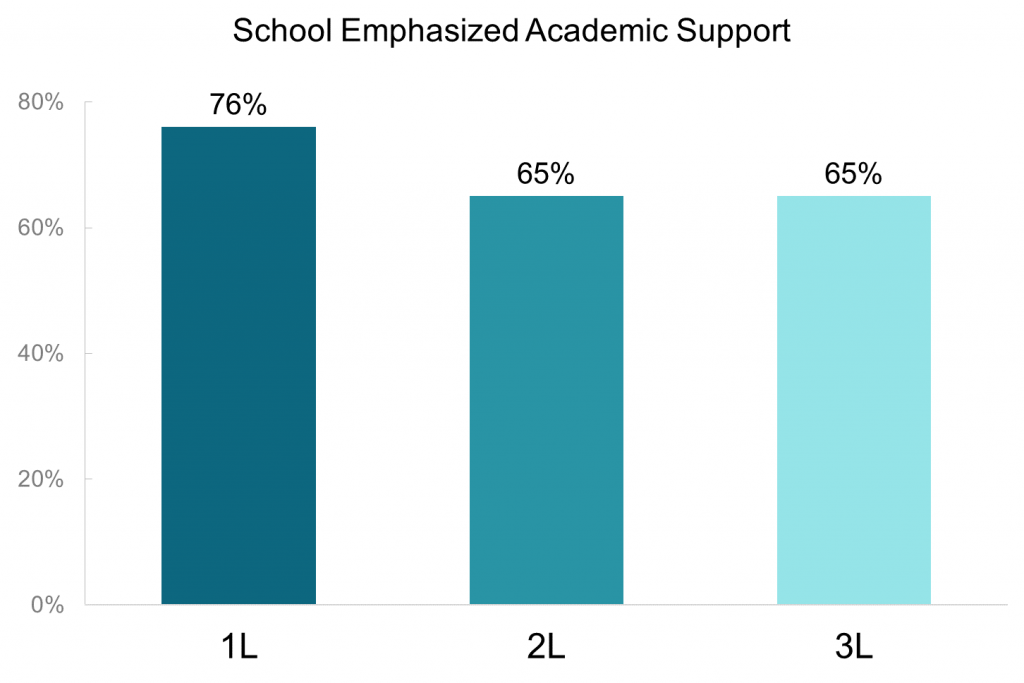

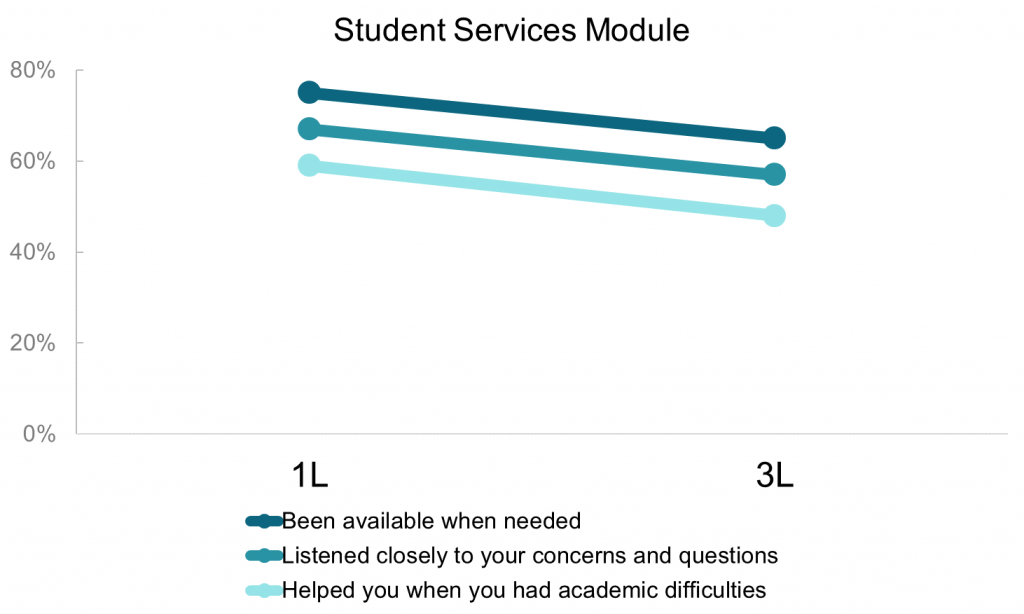

Interactions with academic support personnel drive whether a student would choose to attend the same law school again as well as overall satisfaction with their law school experience. Though students report positive relationships with administrative staff, satisfaction with advising services is less consistent and more varied across race/ethnicity, year in school, and gender. Sixty-nine percent of all respondents report that their law school provides the support they need to succeed academically, with higher perceptions of support among 1L students. Similarly, academic advising, career counseling, and job search help are key support services that students appreciate greatly when they begin law school, though they are more dissatisfied as graduation nears.

Annual Results 2018: Relationships Matter - Student-Faculty Interaction

Faculty, administrators, and classmates are key ingredients to law student success. These relationships serve as important ties to the law school and impact student satisfaction, sense of belonging, and academic and professional development. This year’s annual report explores relationships and examines the nuances of the impact they have on law students.

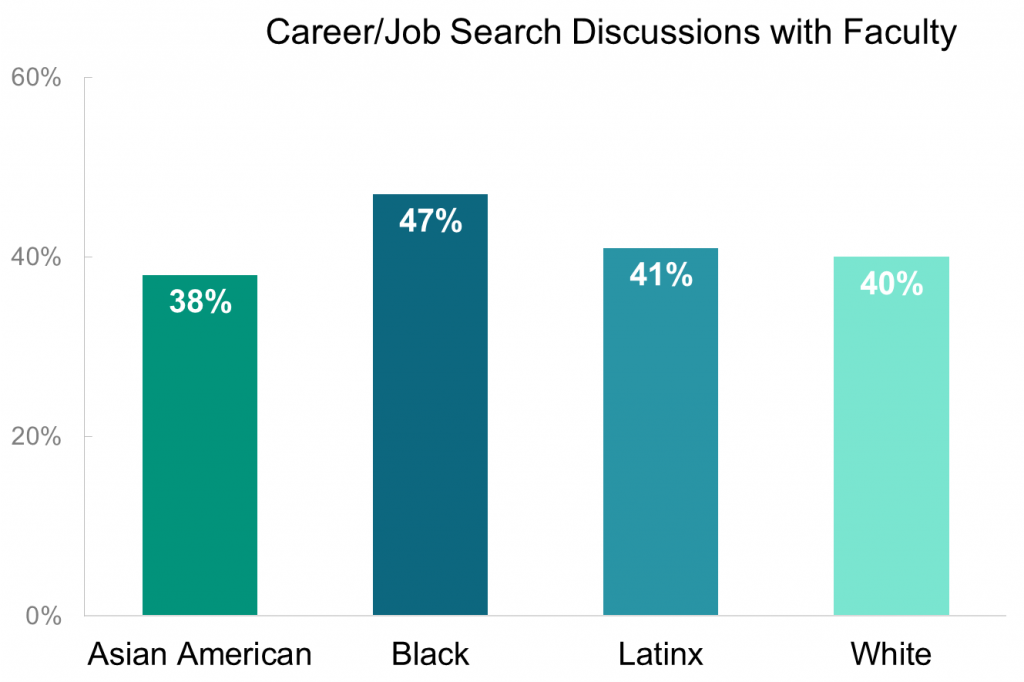

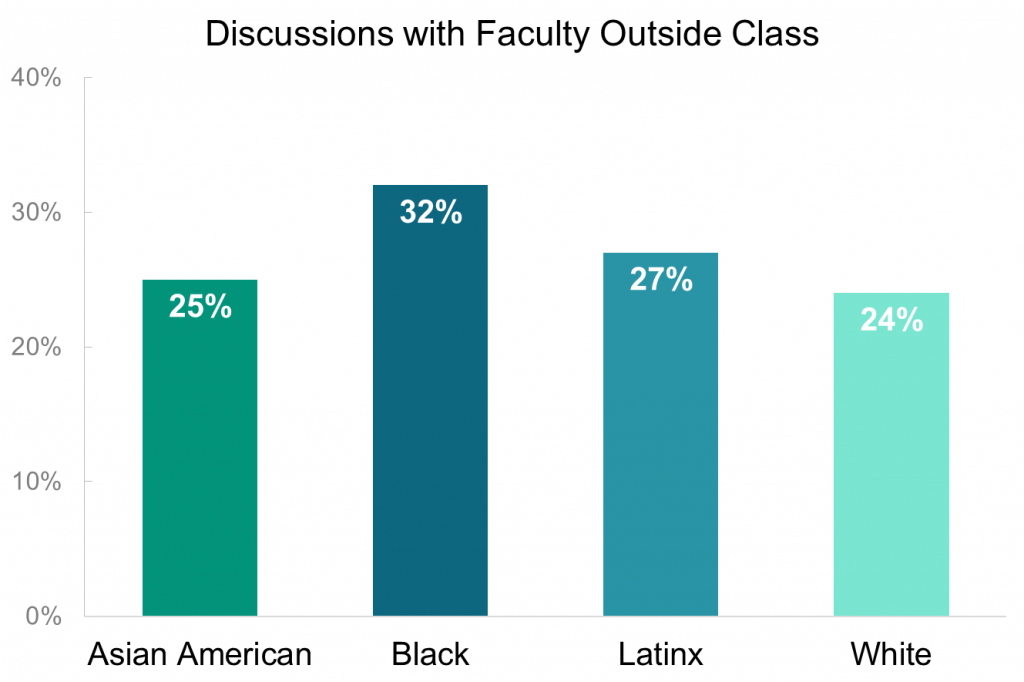

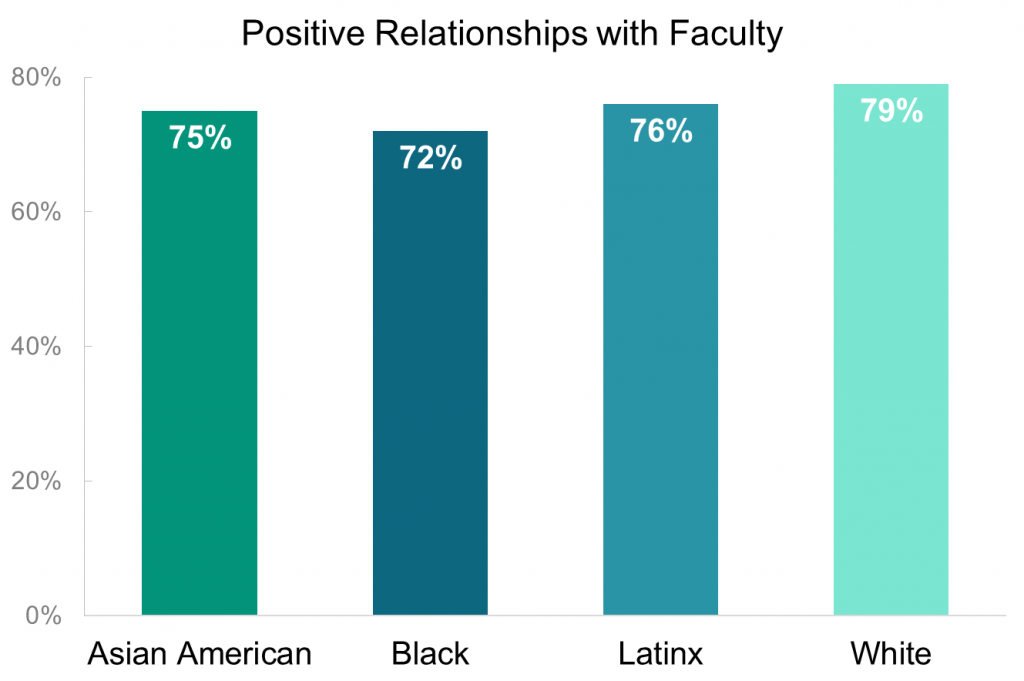

The vast majority of students (76%) report positive relationships with faculty, including interactions both in and out of the classroom. Meaningful interactions vary across student demographics, with notable race/ethnic differences. On multiple dimensions Black and Latinx students report more engagement and interaction with faculty than white and Asian American students. For instance, while a majority of all law students (57%) discuss assignments with faculty “often” or “very often,” 65% of Black students do so, the highest of any racial or ethnic group, followed by 58% of Latinx students, 56% of white students and 53% of Asian American students.

The pattern of Black and Latinx students enjoying higher rates of engagement with faculty persists across multiple dimensions. For example, Black students (47%) are more likely to discuss career or job search with faculty than Latinx (41%), white (40%), or Asian American (38%) students. Black and Latinx students are also more likely to talk with faculty outside of class. The vast majority of students find faculty available, helpful, and sympathetic. Interestingly, this sentiment does not directly track interaction with faculty, as a higher percentage of white students report favorable relationships with faculty than Black and Latinx students.