Focus on First-Generation Students, Part 2

In our last post, we shared some of the demographic characteristics of first-gen law students, which we define as law students who do not have at least one parent with a bachelor’s degree. In this post, we will dig deeper into the first-gen law student experience and how it differs from the experiences of non-first-gen law students.

Time Usage

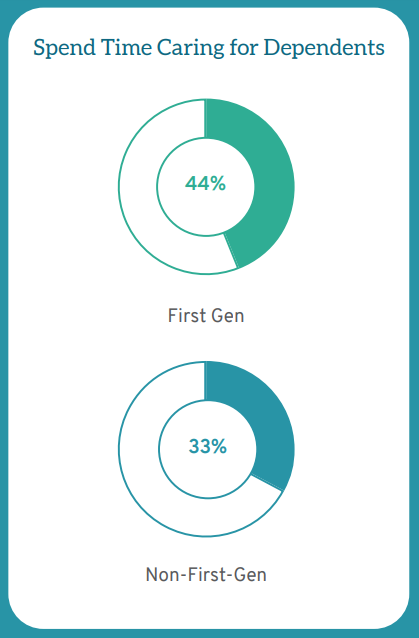

LSSSE asks students to estimate the average number of hours they spend each week engaging in activities that are directly and indirectly related to the educational experience. Time usage is important because it reflects students’ academic engagement and overall priorities. First-gen students are more likely to attend law school part-time, which suggests that they have complicated schedules with competing demands, rather than a sole focus on law school. LSSSE data show that high percentages of first-gen students have familial obligations as caretakers for dependents living in their household. Forty-four percent (44%) of first-gen students spend time caring for dependents, compared to 33% of non-first-gen students.

First-gen students are just as engaged as their non-first-gen peers in academic pursuits outside of class, despite the fact that they have more responsibilities competing for their time. First-gen students work with students and faculty on group projects at equal or greater levels relative to non-first-gen students. Roughly equal percentages of first-gen students (19%) and non-first-gen students (18%) report that they frequently work with faculty members on activities other than coursework (including committees, orientation, student life activities, etc.). Likewise, 33% of first-gen (and 31% of non-first-gen) students frequently work with classmates outside of class to prepare assignments. The diligence of first-gen students is particularly impressive given their personal obligations. One third (33%) of first-gen students always come to class fully prepared despite their family duties and work schedules, the same percentage as non-first-gen students (who tend to work less and have fewer familial obligations).

Satisfaction

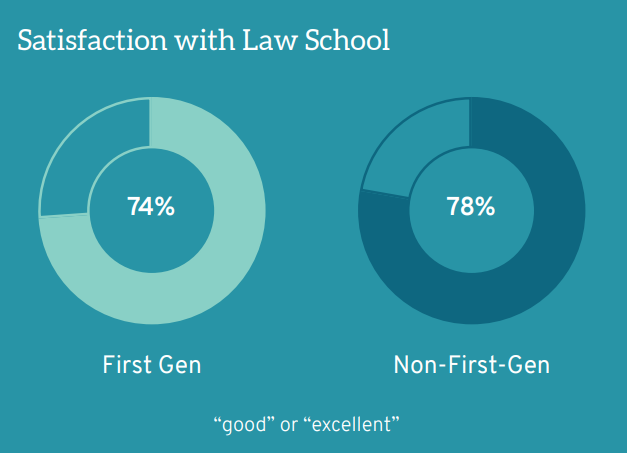

First-gen students, like law students overall, are overwhelmingly satisfied with their law school experience. Seventy-four percent (74%) of first-gen students evaluate the educational experience at their law school as “good” or “excellent,” similar to non-first-gen students (78%). Furthermore, 77% of first-gen (and 79% of non-first-gen) students report they would choose to attend the same law school again, with the benefit of hindsight. These trends are particularly noteworthy given the increased financial risks and other sacrifices made by first-gen students to attend law school.

First-gen students face unique challenges and responsibilities as they navigate legal education. Law schools should take the findings from this Annual Report, as well as their own school-specific LSSSE data, to craft targeted programs to support first-gen students. Better supporting them personally will free up time and resources for first-gen students to devote to not only academics, but other co-curricular pursuits so they are optimally placed to thrive as they enter the legal profession.

SPOTLIGHT ON: Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Law Students

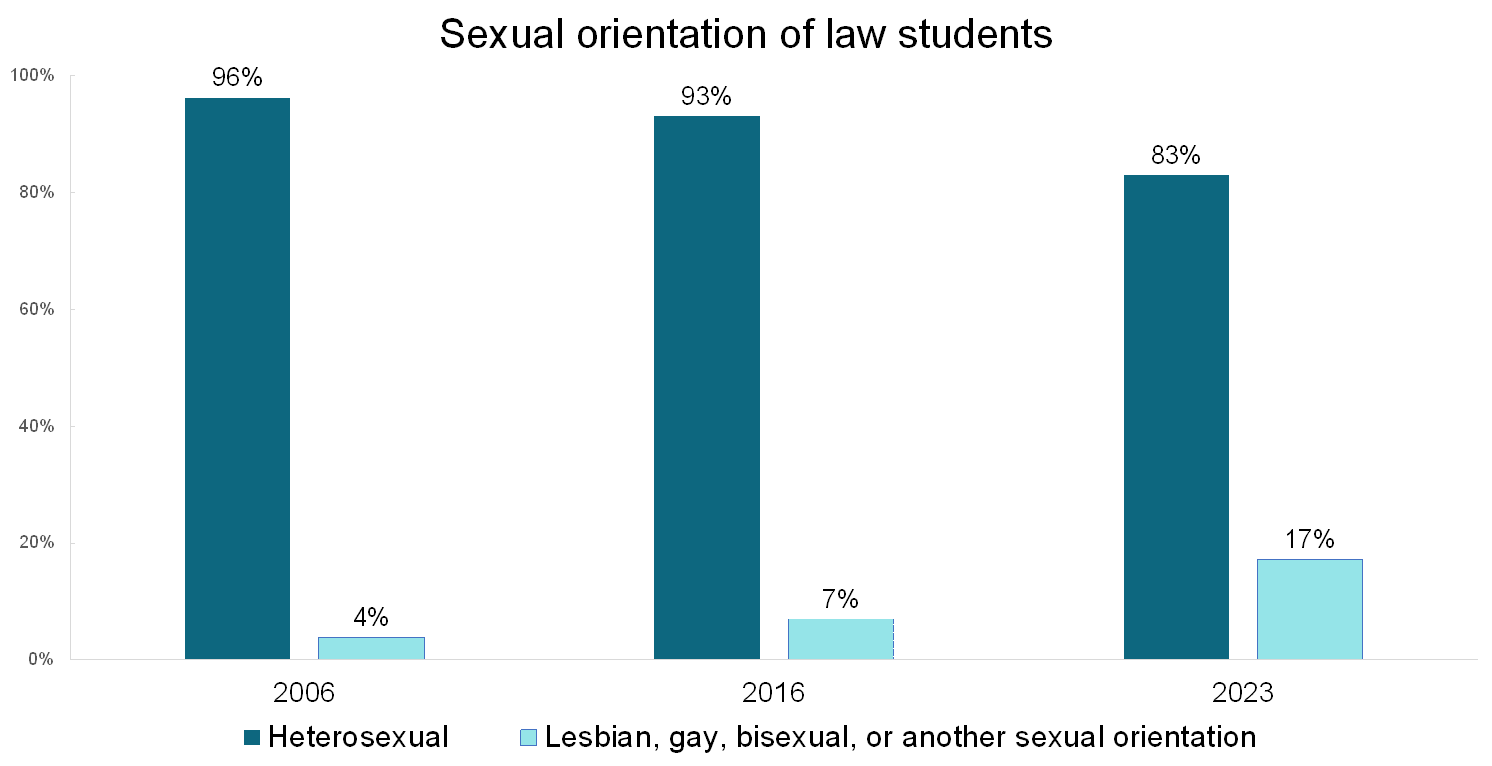

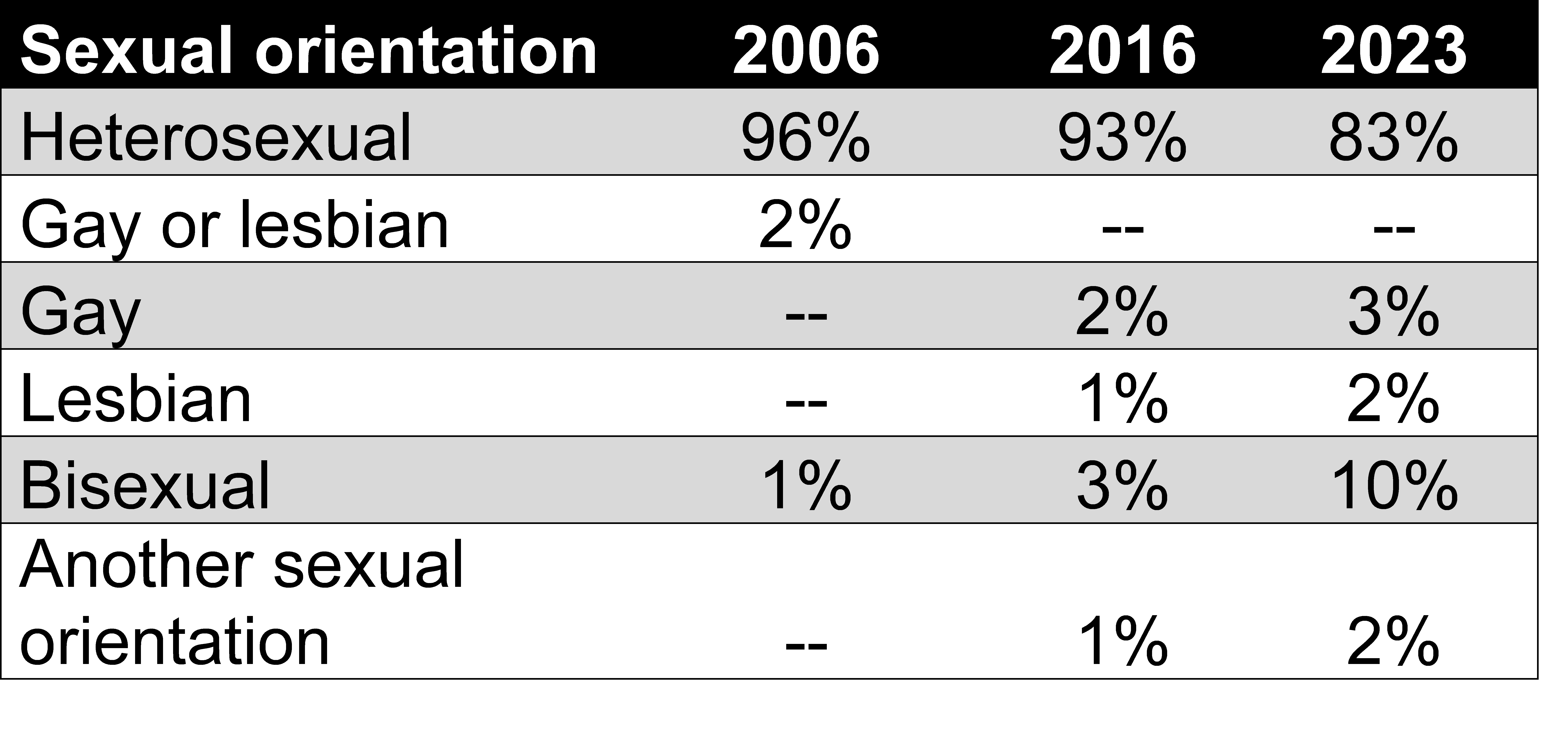

The percentage of law students who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or another non-heterosexual sexual orientation (LGB+) has grown dramatically over the last twenty years. When LSSSE first began asking about sexual orientation in 2006, 96% of law students identified as heterosexual, 2.5% were gay or lesbian, and only 1.3% were bisexual. The numbers had shifted noticeably by 2016, when the sexual orientation question was revamped slightly to be more inclusive. That year, 93% of law students were heterosexual, 2.3% were gay, 1.1% were lesbian, 2.6% were bisexual, and 0.9% were of another sexual orientation. However, by 2023, only 83% of law students identified as heterosexual. Three percent were gay, 1.7% were lesbian, 2% had another sexual orientation, and a full 10% identified as bisexual.

-- indicates response option was not available that year

-- indicates response option was not available that year

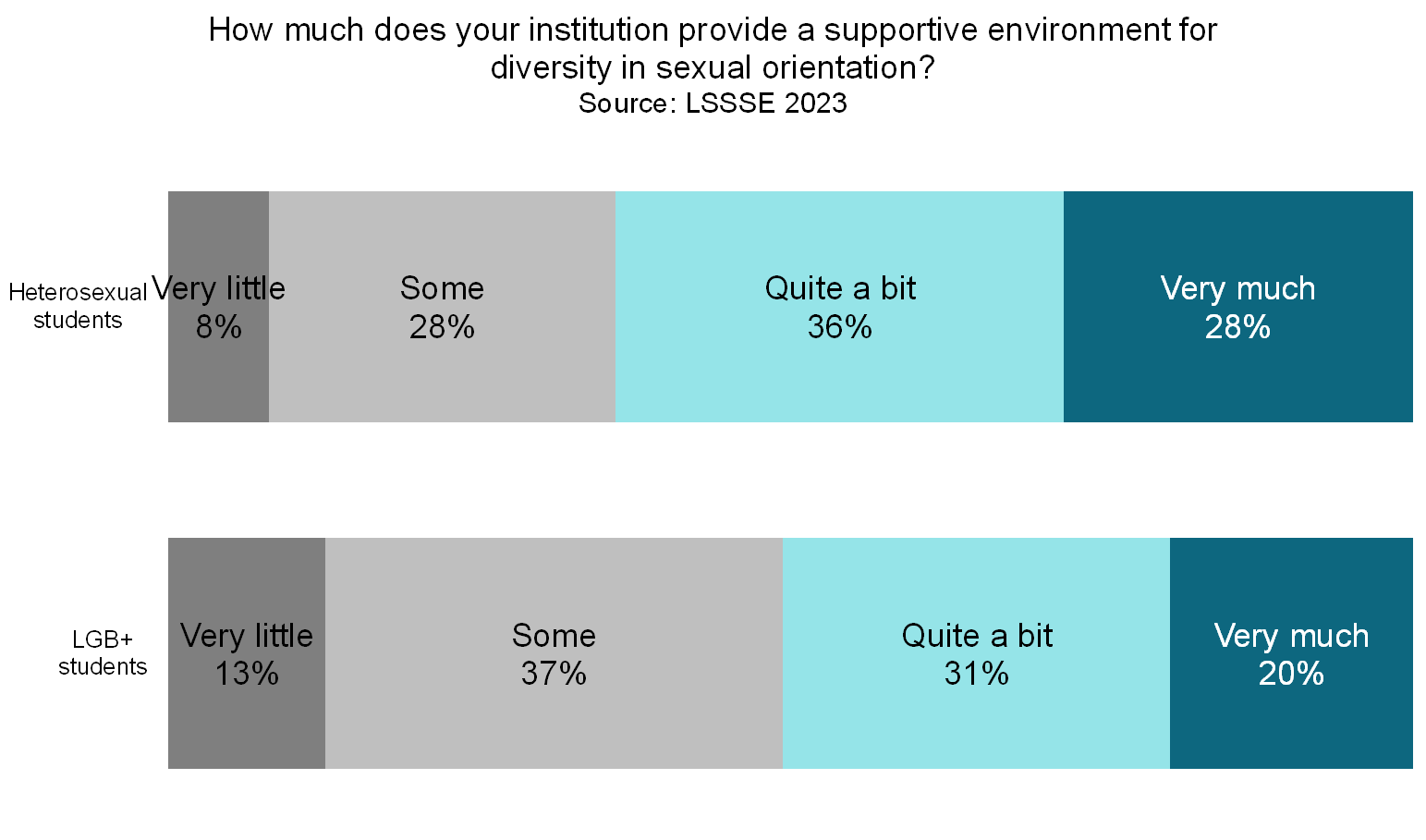

LGB+ students are somewhat less comfortable in law school relative to their heterosexual peers. For example, 72% of LGB+ students feel that they are part of the law school community compared to 77% of heterosexual students. Only half (50%) of LGB+ students believe that their law school places quite a bit or very much emphasis on ensuring that they are not stigmatized because of their identity (racial/ethnic, gender, religious, sexual orientation, etc.) compared to 61% of heterosexual students. Similarly, only about half (51%) of LGB+ students believe that their law school is a supportive environment for diversity in sexual orientation compared to just under two-thirds (64%) of heterosexual students.

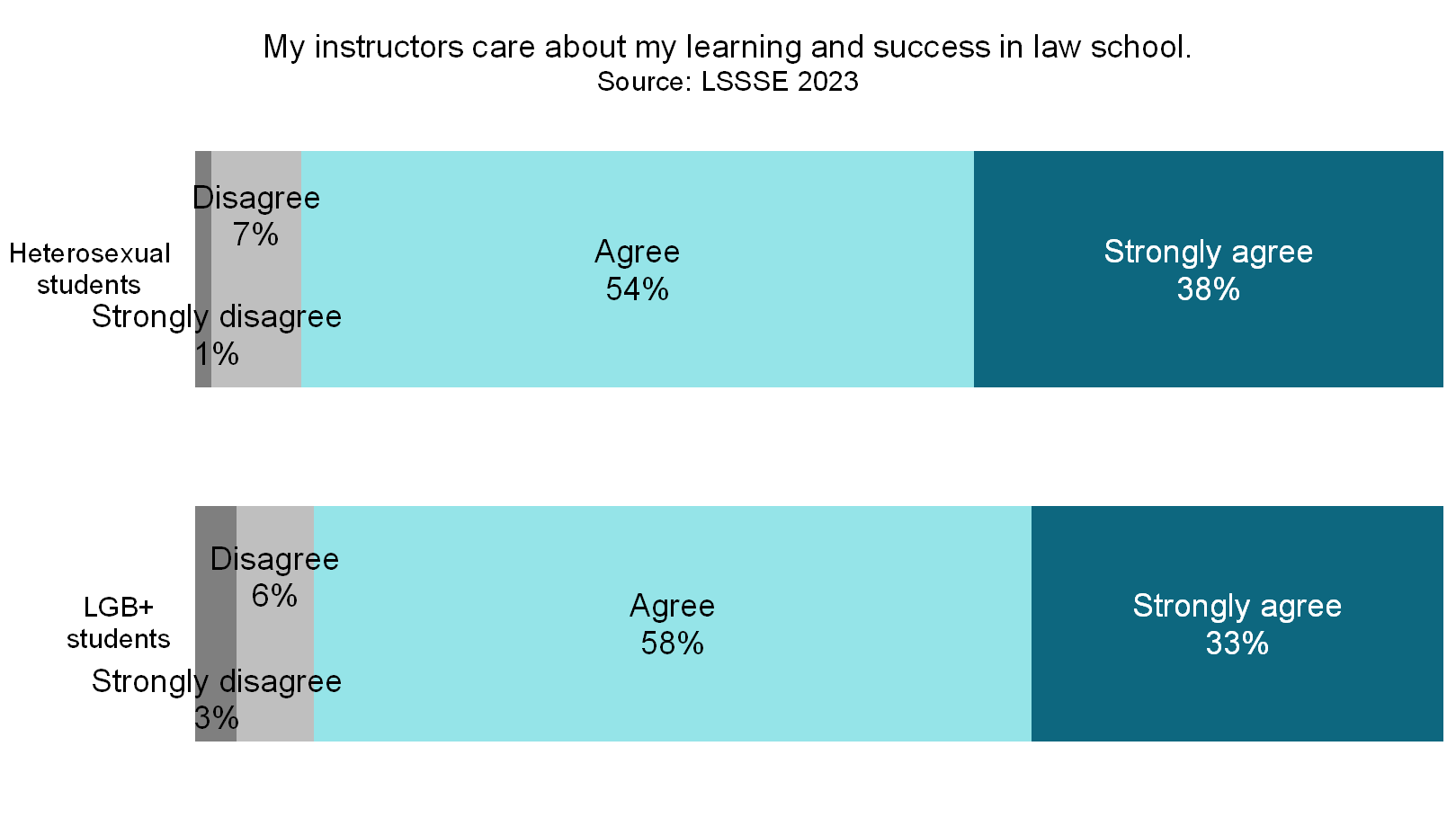

Despite the perception of a somewhat chilly climate overall, LGB+ law students are nearly equally likely as heterosexual law students to have strong relationships with law school faculty. LGB+ students rate their relationships with faculty on average 5.2 on a seven-point scale, compared to 5.3 for heterosexual students. A full 91% of LGB+ students believe their instructors care about their learning and success in law school, nearly equal to the 92% of heterosexual students who feel that way. Around four in five LGB+ and heterosexual students consider at least one instructor a mentor whom they feel comfortable asking for advice or guidance. Clearly, most students find help and support from their law school faculty, regardless of their sexual orientation.

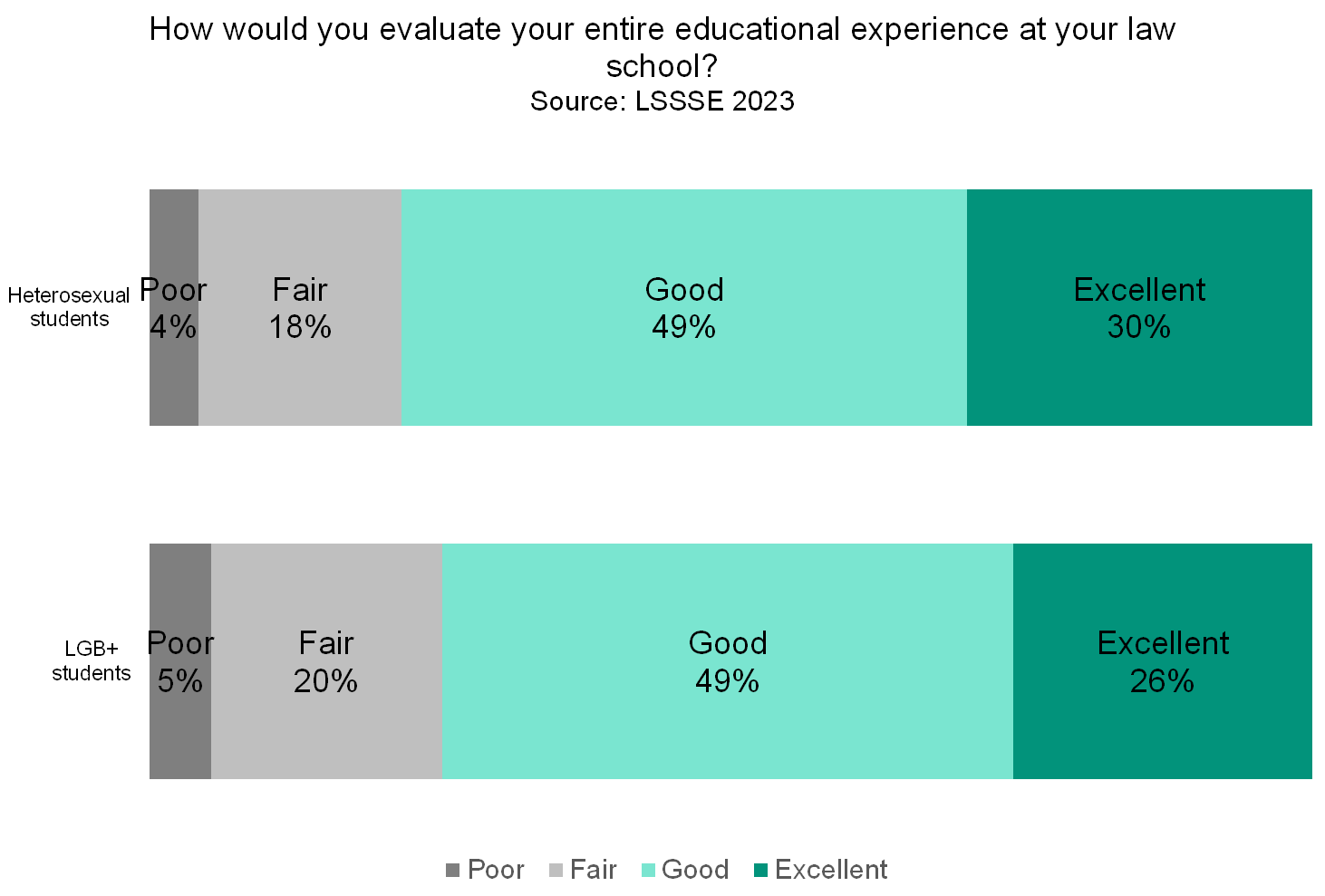

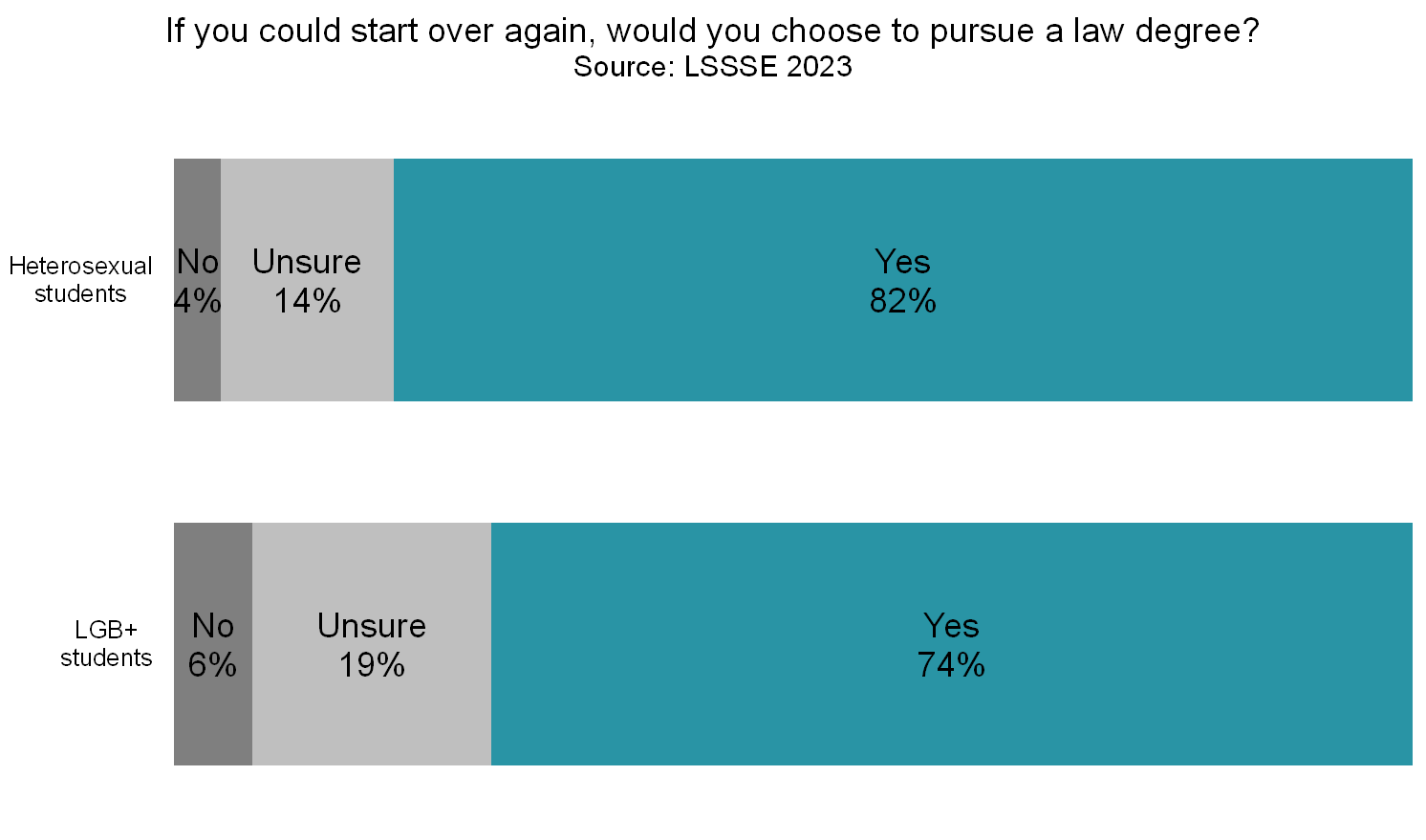

LGB+ students are somewhat less satisfied with their overall experience at law school compared to heterosexual law students. Three-quarters (75%) or LGB+ students rate their experience “good” or “excellent” compared to 78% of heterosexual students. However, LGB+ students are much less likely to be sure that they would pursue a law degree if they could start over. Just under three-quarters (74%) of LGB+ students said they would pursue a law degree and 19% were unsure. More than four in five (82%) heterosexual students would choose law school again and only 14% were unsure. Clearly, LGB+ law students are more likely than heterosexual law students to have regrets or misgivings about the path they selected.

Given that the population of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and other non-heterosexual students is growing rapidly in law schools, the concerns that these students have about the law school experience deserve particularly careful attention. LGB+ law students are less likely to feel that they belong, more likely to feel stigmatized, and more likely to question whether attending law school was the correct choice for them. Interestingly, most LGB+ students feel that their instructors care, and they are equally likely as heterosexual students to have an instructor that they consider a mentor. Perhaps law schools can use these personal connections to identify and address the concerns of their lesbian, gay, bisexual, and other non-heterosexual students in order to ensure equitable educational opportunities and a more supportive law school environment.

Law Students are Generally Quite Happy Wherever They Land

The choice of where to apply to law school is an important one. When evaluating law schools, most prospective law students thoroughly research the quality and reputation of the program, the extracurricular and employment opportunities it may provide, the campus climate, the cost of living, and other personally relevant factors. After applying, students must choose among the offers of admission they receive, which may or may not include an offer to their first-choice law school. We wanted to know how law students fare after matriculation. Does attending a first-choice or a non-first-choice law school have a large impact on student satisfaction? Do students who are attending their second or third choice have regrets, or would they make the same decision if they could start over again with the benefit of hindsight?

LSSSE includes the following three questions that help us disentangle several factors related to law school choice and satisfaction:

- Was the law school you are attending your first-choice law school as an applicant? Response options: No, Yes

- If you could start over again, would you attend the SAME LAW SCHOOL you are now attending? Response options: Definitely no, Probably no, Probably yes, Definitely yes

- How would you evaluate your entire educational experience at your law school? Response options: Poor, Fair, Good, Excellent

If you could start over again, would you attend the SAME LAW SCHOOL you are now attending?

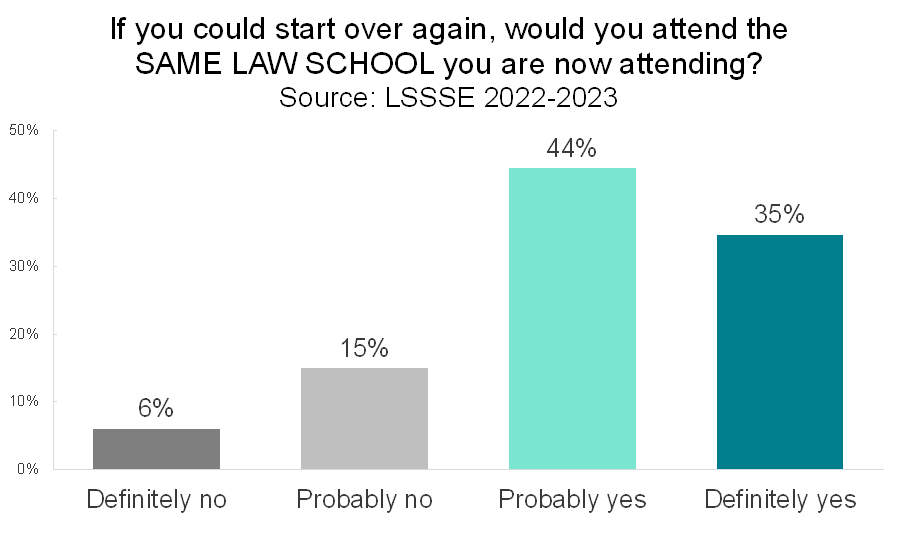

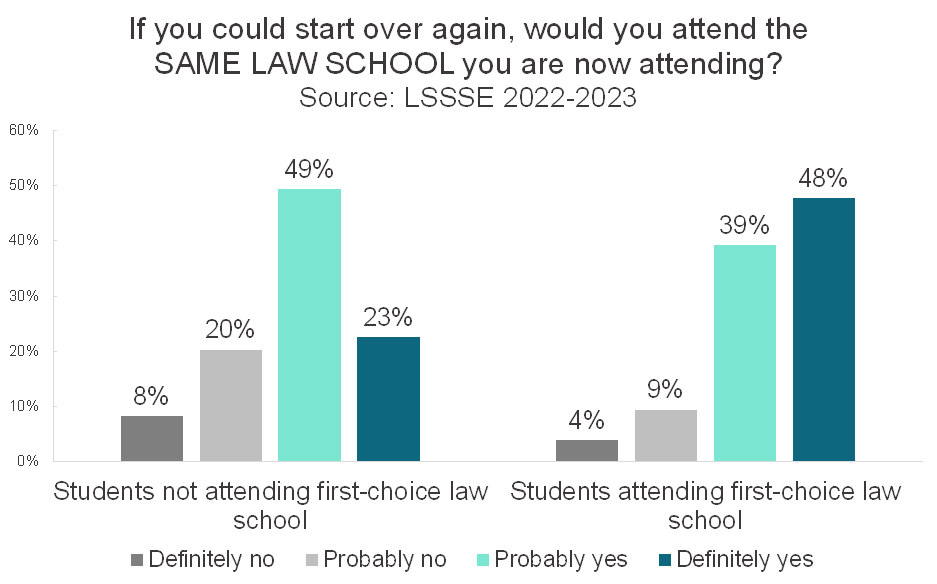

Slightly less than half of law students attend their first-choice law school. Among students surveyed in 2022 and 2023, 52% of law students were not attending their first-choice school compared and 48% of law students who were. Across the entire population, most law students would choose the same law school if they could start over again. Nearly four out of five (79%) of law students would probably or definitely attend the same school. A mere 6% of law students definitely would not.

Understandably, students attending their first-choice school were highly likely to say that they would make the same choice of law school again. A full 87% of these students would probably or definitely choose their law school again, and only 4% definitely would not. However, remarkably, students not attending their first-choice school were also quite likely to say that they would attend the same school if they could start over again. Nearly three-quarters (72%) of students not attending their first-choice law school would likely choose the same law school they are attending if they could start over. Only 8% of students at their non-first-choice school would definitely not choose to attend that school, and one in five (20%) said they probably would not

How would you evaluate your entire educational experience at your law school?

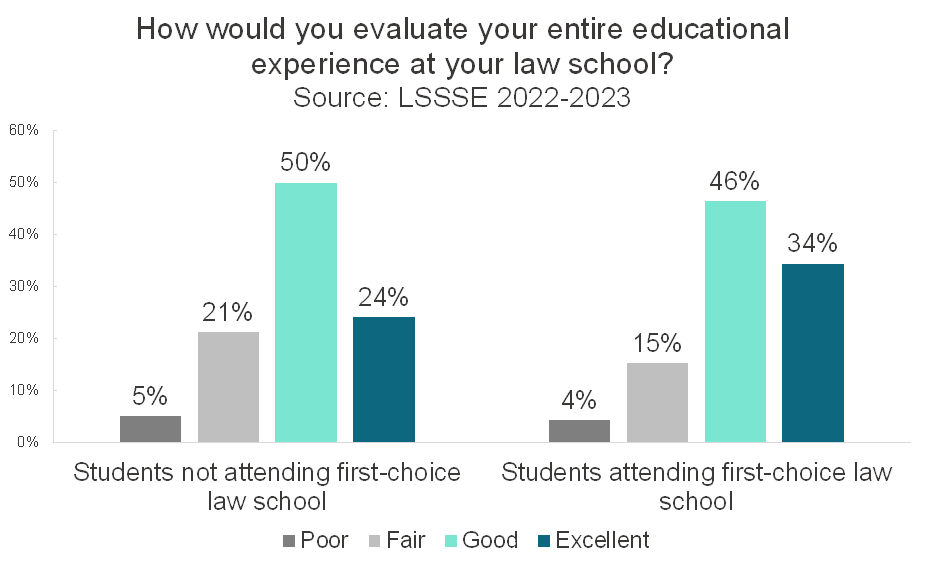

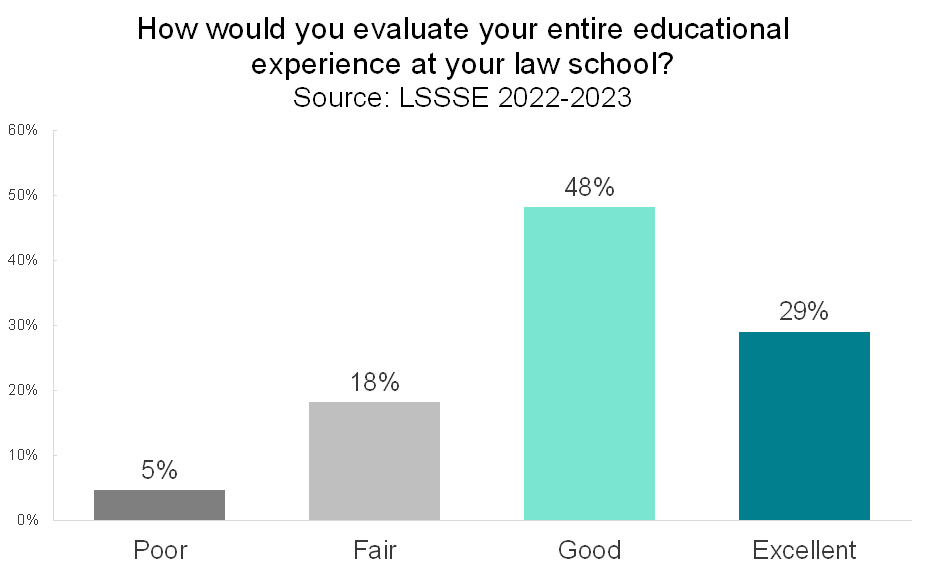

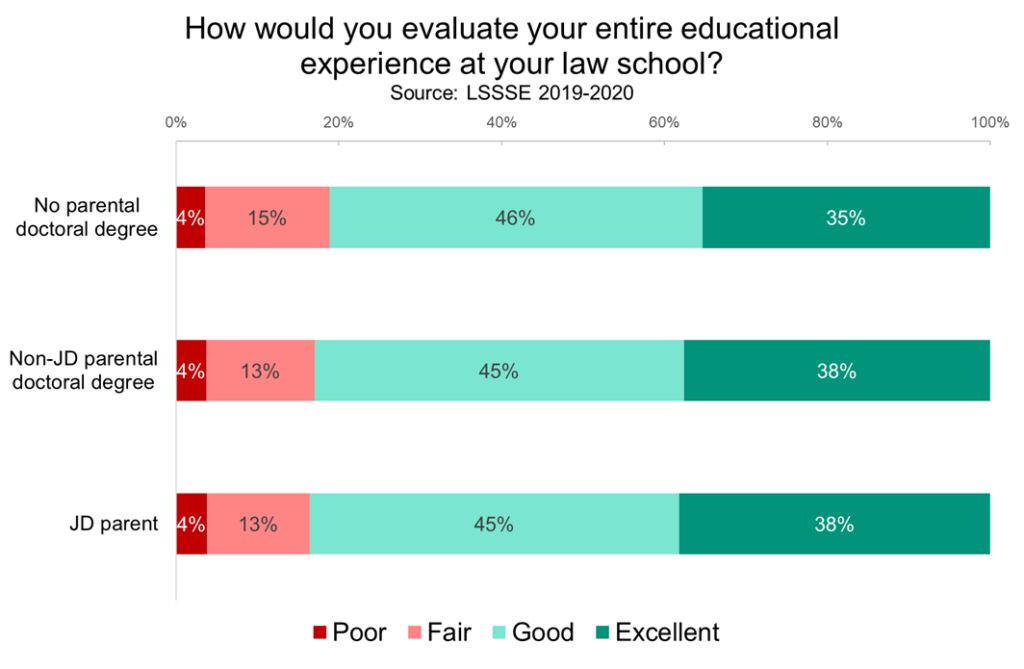

LSSSE has found consistently since the inaugural survey in 2004 that law students tend to be highly satisfied with their law school experiences. The two most recent survey years show that 77% of law students rate their experiences highly, with 48% saying their entire education experience is “good” and 29% saying it is “excellent.”

Again, there are disparities between students who are attending their first-choice law schools and students who are not, but the differences are quite modest. Eighty percent of students attending their first-choice school are satisfied compared to 74% of students not attending their first-choice school. A small and nearly equal percentage of students from both groups say that their entire educational experience has been “poor." It seems that most law students find ways to learn and thrive in the environment where they land, even if it not what they had thought would be their ideal situation before beginning law school.

Prospective law students should take heart in these findings. Although the choice of law school seems incredibly important during the application and admission process, most law students ultimately feel quite satisfied with their choice of law school, even if it wasn’t the school they might have preferred initially. And if they could start over, most law students would likely choose their own law school all over again.

Part 2: Part-Time Students & the Law School Experience

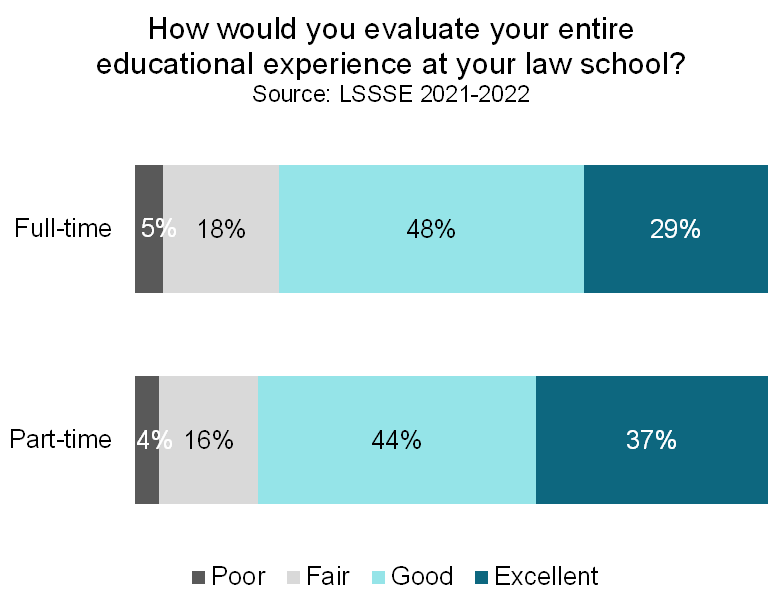

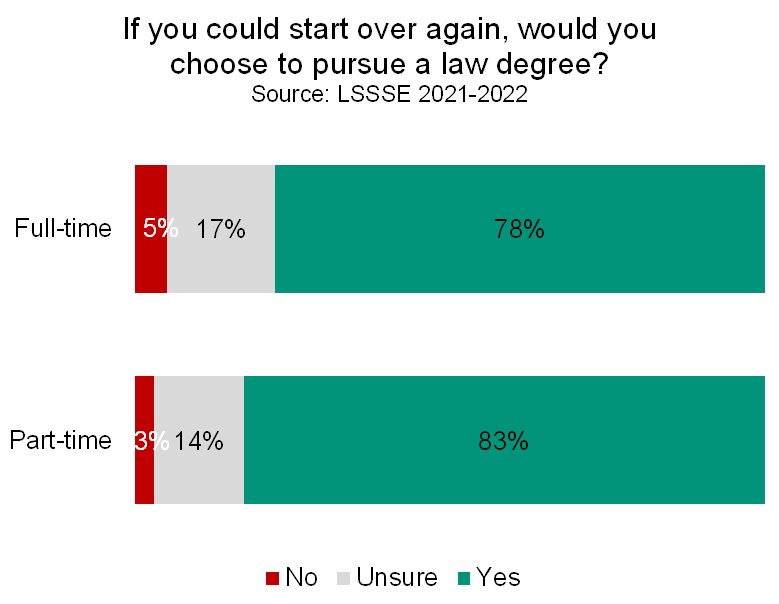

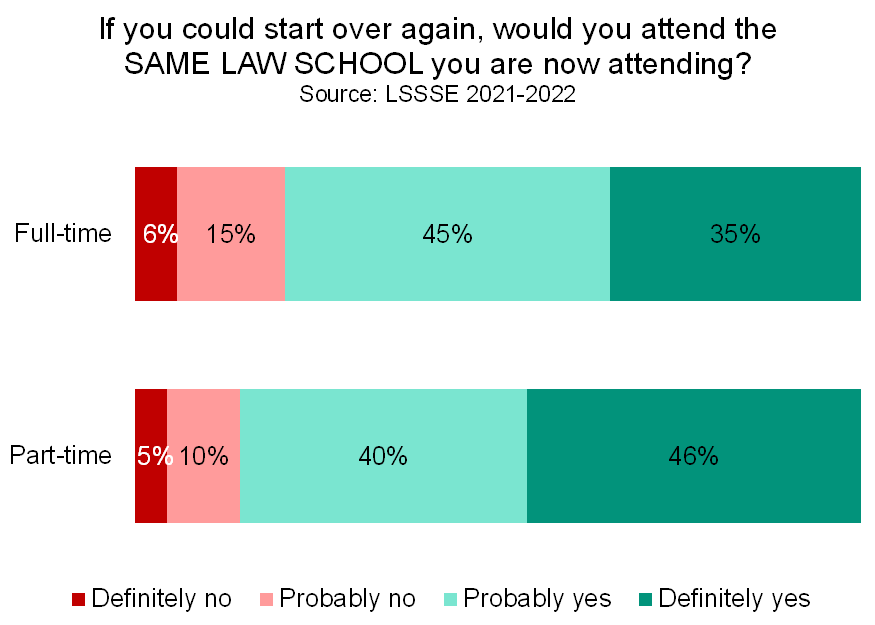

Part-time law students tend to be particularly happy law students. Four out of five part-time students (81%) rate their overall law school experience as good or excellent compared to 77% of full-time students. In fact, 37% of part-time students give their school an excellent rating compared to just 29% of full-time students. Most part-time students (83%) would choose to attend law school again if they could start over, and a similarly high proportion (86%) would choose the same school they are currently attending.

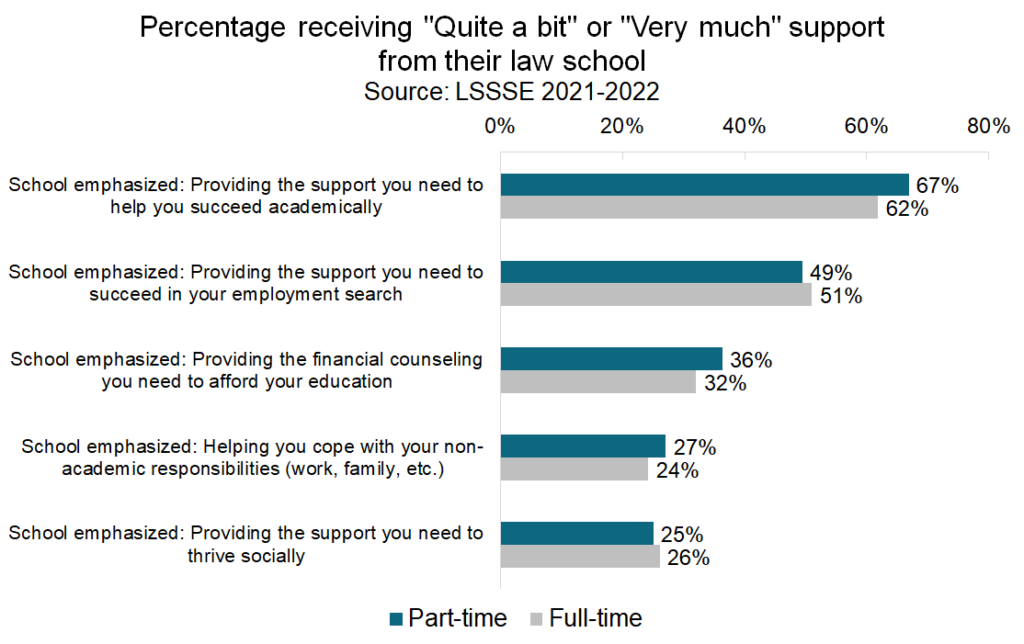

Part-time students feel a level of support from their law schools that is generally on par with – or higher than – the level of support experienced by their full-time colleagues. Two-thirds of part-time students feel that their school is providing the support they need to succeed academically. Around half feel that their law school is providing the support they will need to succeed to succeed in finding employment. Only a quarter of part-time students feel that their school provides the support they need to thrive socially, although this is nearly identical to the 26% of full-time students who feel similarly. Part-time students may require somewhat different considerations than their full-time peers, but they generally feel that their law schools provide adequate assistance to allow them to be successful.

Part-time students feel a strong connection to their law schools. They are fairly satisfied with the resources their law schools provide, and they are quite satisfied with their overall experiences as law students. Although their experiences as law students may be slightly untraditional, they are still highly engaged and active participants in their programs of legal study.

New Questions Focusing on Law Students with Disabilities

By popular demand, LSSSE is now capturing information about the experience of law students with disabilities. Law students are given the opportunity to select one or more conditions using the following questions:

Have you been diagnosed with any disability or impairment?

- Yes

- No

- I prefer not to respond

Which of the following impacts your learning, working, or living activities?

- Sensory disability

- Blind or low vision

- Deaf or hard of hearing

- Physical disability

- Mobility condition that affects walking

- Mobility condition that does not affect walking

- Speech or communication disorder

- Traumatic or acquired brain injury

- Mental health or developmental disability

- Anxiety

- Attention deficit or hyperactivity disorder (ADD or ADHD)

- Autism spectrum

- Depression

- Another mental health or developmental disability (schizophrenia, eating disorder, etc.)

- Another disability or condition

- Chronic medical condition (asthma, diabetes, Crohn’s disease, etc.)

- Learning disability

- Intellectual disability

- Disability or condition not listed

- Please describe your disability or condition

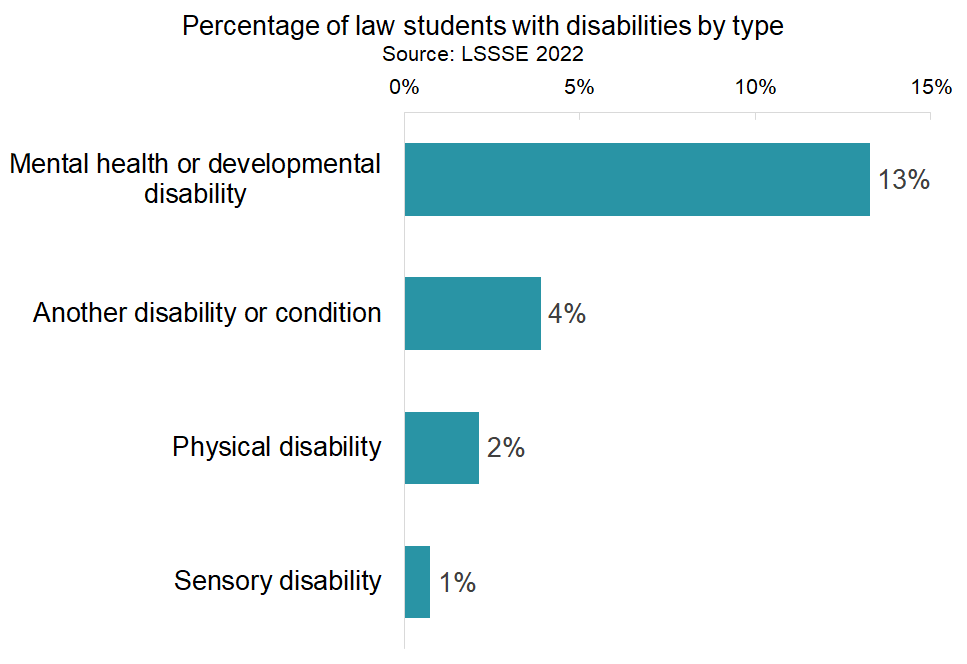

In 2022, nearly one in five (19%) of LSSSE respondents had a disability. Students who responded "yes" to the disability question then had the option to select the condition(s) that impact their learning, working or living activities. Mental health conditions were by far the most common, with about 13% of law students having a condition such as anxiety, ADHD, or autism. Four percent of law students had a condition not specified on the survey such as a chronic health condition or a learning disability. Two percent of respondents had a physical disability, and one percent had a sensory disability such as being deaf or hard of hearing.

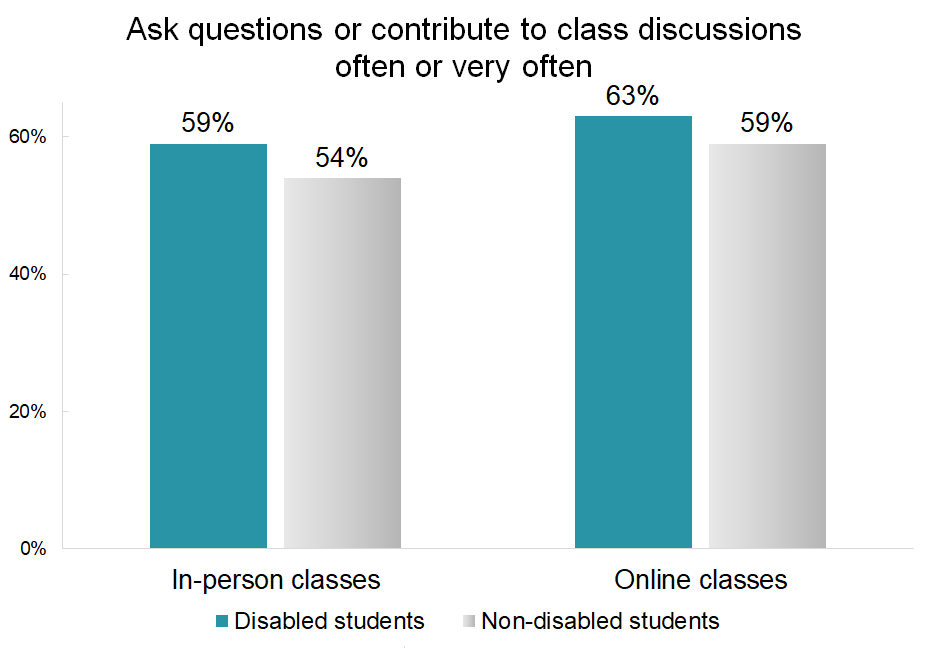

In addition to tracking the overall proportion of law students who are disabled, these new data give us an exciting opportunity to explore how students with disabilities might engage differently with their law schools and what particular experiences or services law schools can offer to better help these students succeed as professionals. For example, law students who have a disability are more likely to participate in class discussions, both online and in person, compared to their non-disabled peers. Additionally, students with disabilities are more likely to engage in pro bono work or public service during law school. Near four out of five students with disabilities (79%) either plan to or have done pro bono work or public service compared to 74% of non-disabled students.

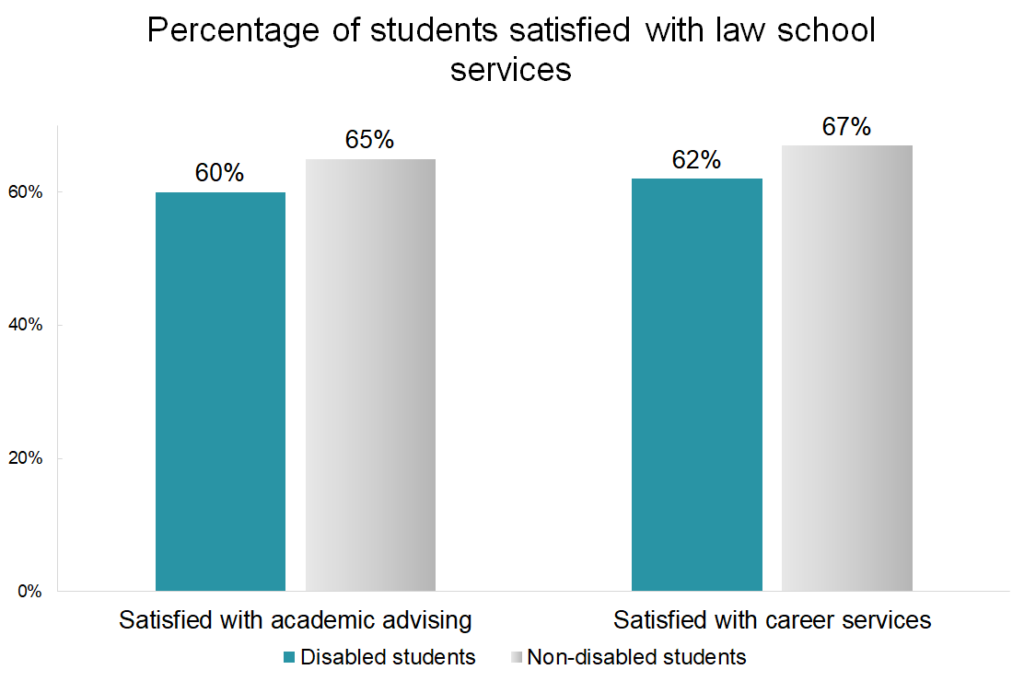

However, disabled students are less likely to be satisfied with their experiences with academic advising and career advising compared to their classmates. This suggests that law students with disabilities engage intensely with the law school experience but do not always feel as supported as their non-disabled peers.

The new disability questions are included in the core LSSSE survey and available to all participating law schools. Survey registration will be opening soon; contact LSSSE for more details!

Providing the support law students need to succeed academically

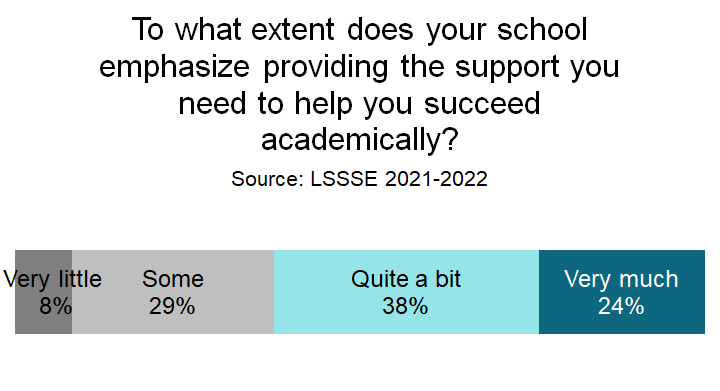

A strong academic program is the foundation of any law school. Equally important is that law schools provide the support services students need to meet the rigors of the curriculum. About two-thirds of law students feel that their law school places “quite a bit” or “very much” emphasis on providing the support they need to succeed academically.

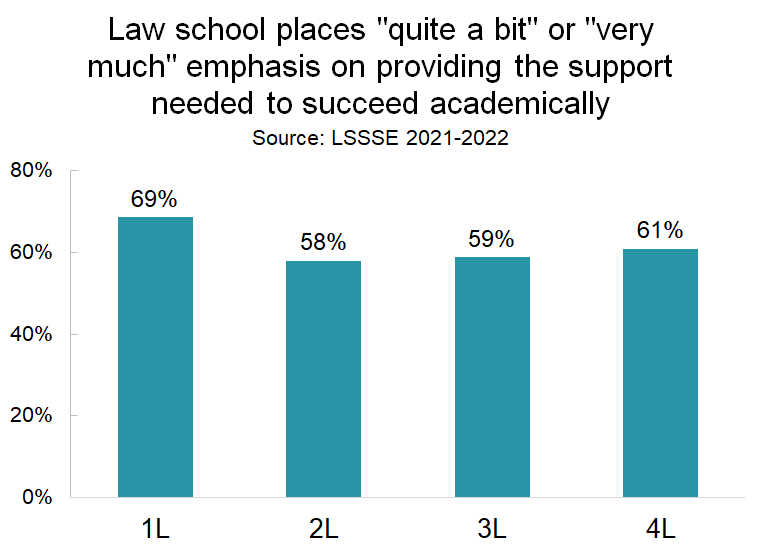

1L students are more likely to feel supported than their more advanced colleagues. Although the general optimism and positivity that 1L students feel toward their experience tends to steadily decline with advancing years for any measure of engagement, for the perception of academic support, satisfaction drops markedly among 2L students and then remains at that level during 3L and 4L years. This suggests that there is an initial sense of being supported that fades fairly quickly after students adjust to their new environment.

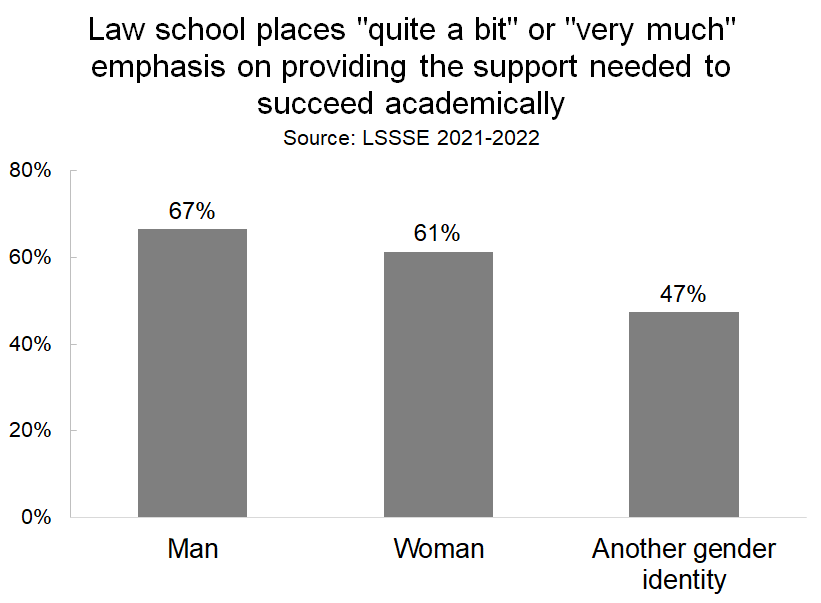

Two-thirds of men feel that their law schools places a strong emphasis on supporting academic success, which is slightly higher than the proportion of women who feel similarly (60%), but fewer than half of the people who have another gender identity feel that level of academic support.

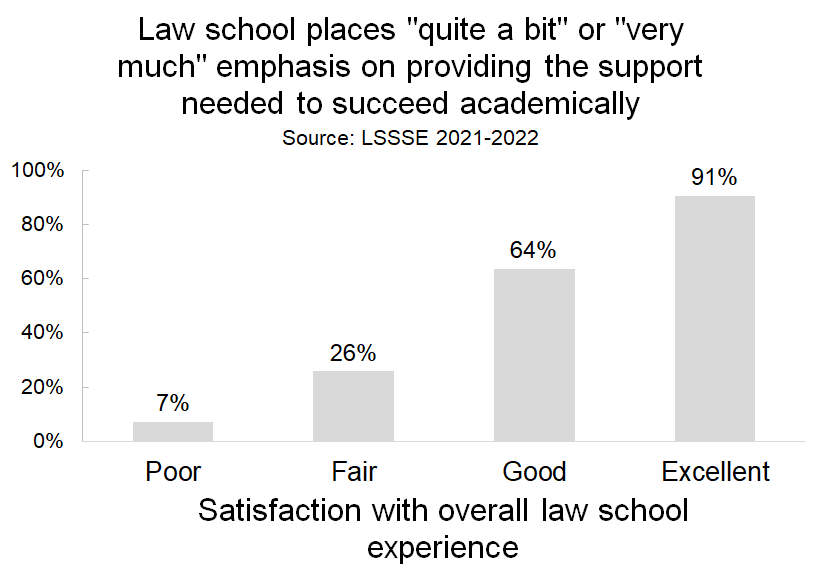

Importantly, the degree to which students feel academically supported is very strongly correlated with whether they are satisfied with their overall law school experience. A full 91% of students who rate their experience as “excellent” feel supported in their academic success compared to only 7% of students who have are having a “poor” experience.

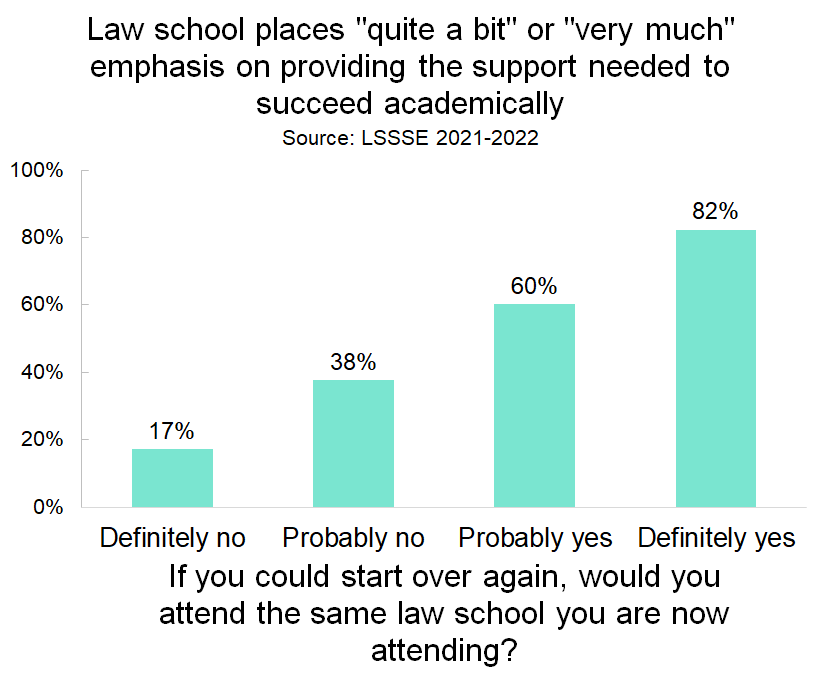

Perceived degree of academic support is also closely tied to whether a student would choose their law school again if they could start over, although the relationship is slightly less stark than for overall law school satisfaction. Among students who would either probably not or definitely not attend the same school, about 32% feel supported to succeed academically. But among students who would probably or definitely attend the same school, 70% feel academically supported.

Law students are driven to succeed in the face of the challenges presented by their academic program. Students who feel supported in their academic endeavors by their schools are more likely to be satisfied with their overall experience and to say that they would choose the same school if they could start over. Academic support is integral to a successful law school experience and likely impacts students’ long-term satisfaction and likelihood to become alumni who speak highly of their alma maters.

Part 1: The COVID Crisis in Legal Education: Impact on Core Mission and Enriching Experiences

Because LSSSE has been annually administered since 2004, the survey was well-positioned to capture shifts in students’ perceptions and behaviors during the uniquely challenging 2020-2021 academic year. Our 2021 Annual Results, The COVID Crisis in Legal Education (pdf) draws from the core survey and two new modules (“Coping with COVID” and “Experiences with Online Learning”) to identify key struggles and successes of legal education during a period marked by uncertainty and disruption.

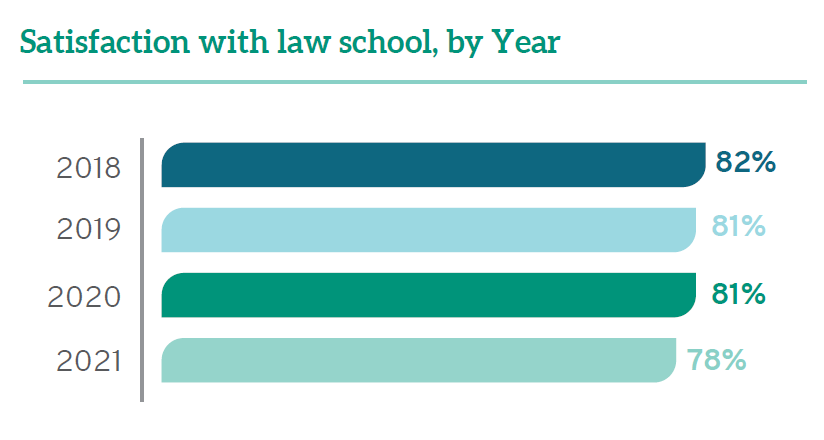

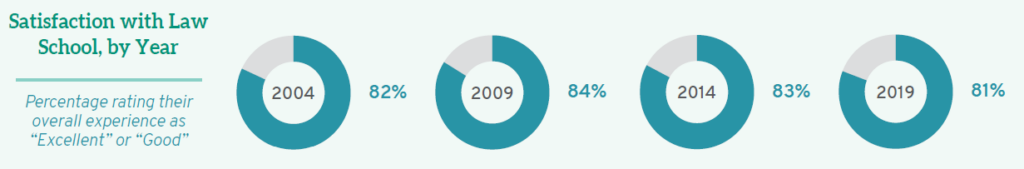

In the midst of a challenging year, some positives emerge from the data. Overall satisfaction remained high throughout legal education and comparable to past years. A full 78% of students in 2021 rated their entire educational experience in law school as “good” or “excellent,” which is similar to rates from recent years (82% in 2018, and 81% in 2019 and 2020). This is a testament to the significant efforts of faculty, staff, and administrators who pivoted to meet student needs as well as to the resiliency of the students themselves.

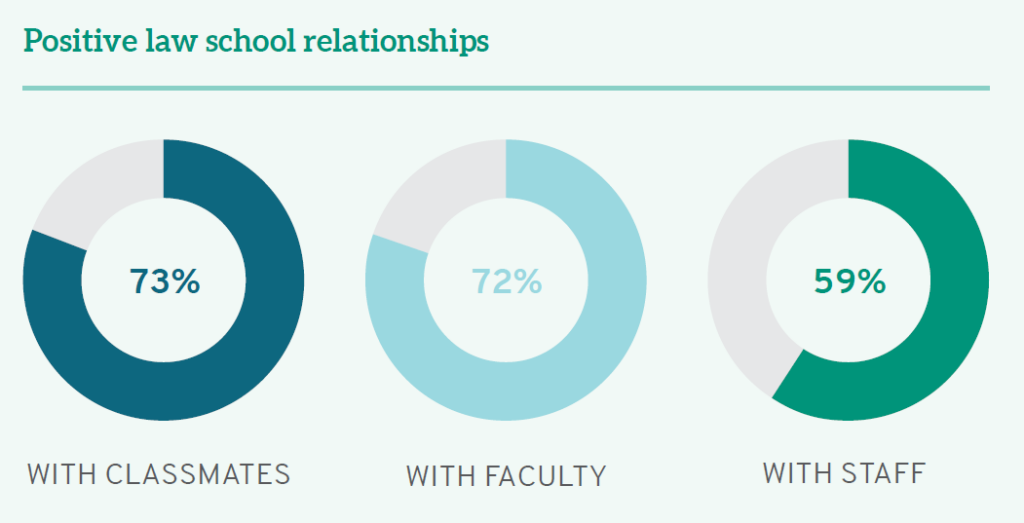

Nevertheless, the ability to forge and foster relationships has been especially difficult during the pandemic, which is borne out in the data. The percentage of students reporting positive relationships with staff dropped from 68% in 2018 to 59% in 2021—the lowest percentage recorded since LSSSE began collecting data on student-staff interactions in 2004. During those same years, positive student relationships with faculty and fellow students dropped just slightly from 76% to 72% and 76% to 73%, respectively. A full 93% of students appreciated that their law professors showed “care and concern for students” as the pandemic raged around them. First-year students were less likely to report positive relationships than 2Ls and 3Ls—likely because upper-class students could build on foundations they had cemented pre-COVID while 1Ls were attempting to start relationships from scratch in the midst of the pandemic.

The core of legal education remains relatively unchanged. Every year from 2018 to 2021, 85% of students have acknowledged that their schools contributed “quite a bit” or “very much” to their ability to acquire a broad legal education. There were also minimal changes this year compared to years past with regard to students developing legal research skills (80- 83%) and learning effectively on their own (81-82%).

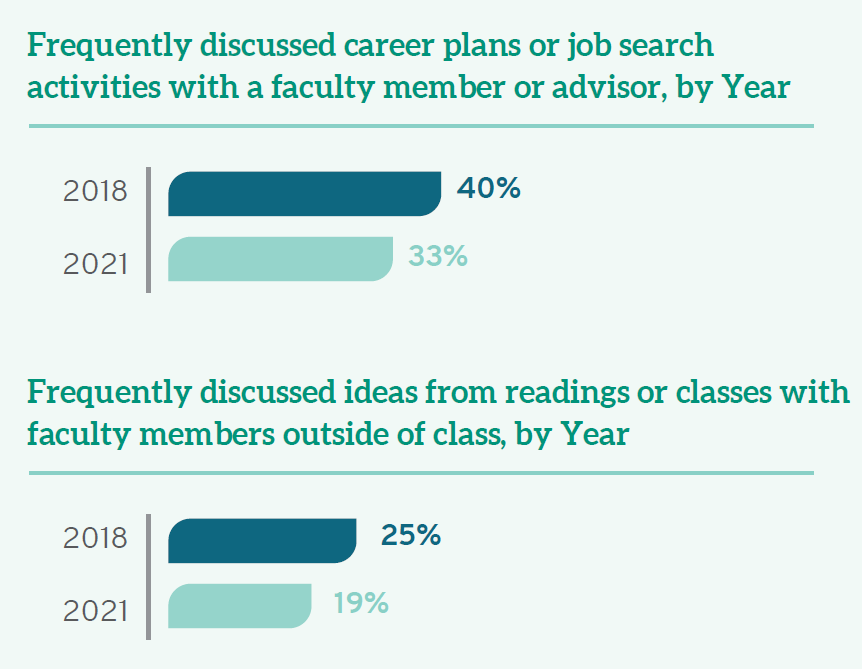

Yet the intangibles of legal education were significantly affected by COVID-19, with potential negative consequences on the professional competency of these future lawyers. A full 90% of students noted that COVID interfered with their ability to participate in special learning opportunities, including study abroad, internships, and other field placements. While discussions about course assignments and faculty feedback on academic performance remained constant, just one-third (33%) of all law students found frequent occasions to talk with faculty members or other advisors about career plans or the job search process (down from 40% in 2018), and only 19% frequently discussed ideas from readings or classes with faculty members outside of class (down from 25% in 2018). There were also fewer opportunities for students to work with faculty members on activities other than coursework.

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted nearly all aspects of life, and law school is no exception. Although law schools did their best to continue on with the education of the next generation of lawyers, there were still marked decreases in student engagement, particularly in building relationships and gaining experience outside the classroom. In our next post, we will explore the areas in which law students struggled the most in their lives and show how the pandemic disproportionately impacted those students who were already the most vulnerable.

The Changing Landscape of Legal Education: High Levels of Satisfaction

In spite of many challenges, law students report relatively constant positive levels of satisfaction with legal education over the last decade and a half. Our 2020 special report The Changing Landscape of Legal Education: A 15-Year LSSSE Retrospective shares longitudinal findings on select metrics as well as demographic differences within variables to catalog how legal education has changed over time. In this blog post, we highlight the remarkably high levels of satisfaction that students have expressed about their law school experience since LSSSE’s inception.

When students were asked, “How would you evaluate your entire educational experience at your law school?” over eighty percent of all law students rated their experience as at least “good” with roughly one-third of all students saying they have enjoyed an “excellent” law school experience.

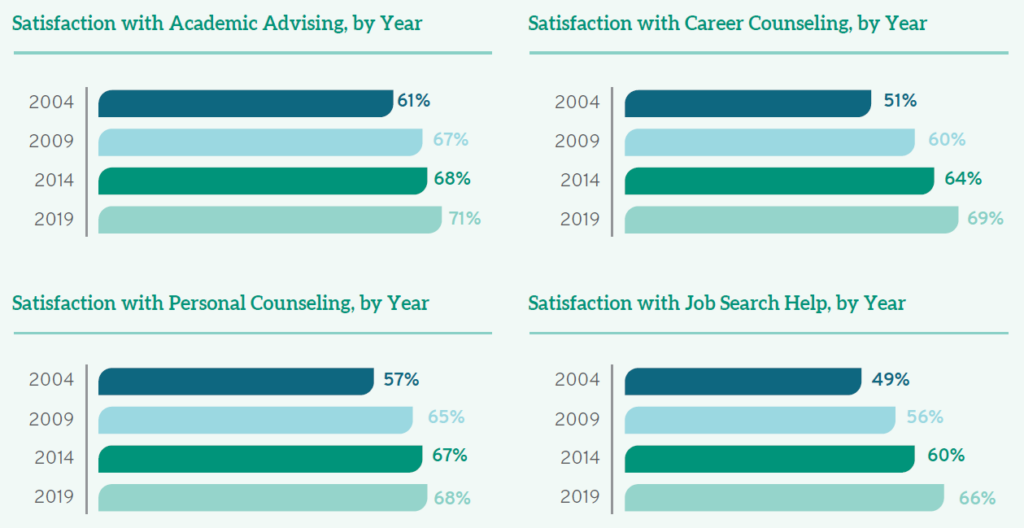

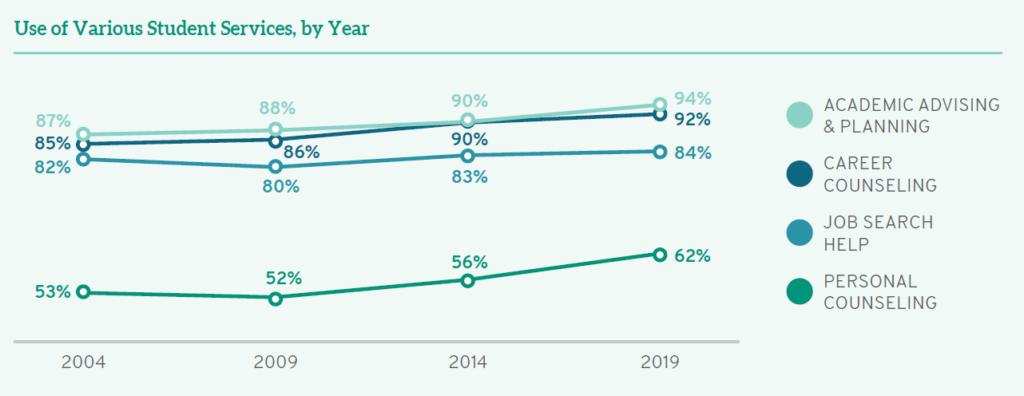

If we consider student satisfaction with a number of different encounters—including academic advising, career counseling, personal counseling, and job search help—we see a consistent pattern of improvement over fifteen years. While over half (53%) of students who sought out academic support were “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with advising and planning in 2004, that number grew to almost three quarters (71%) of all students by 2019. Interestingly, there are also more students using academic advising and planning today than in years past: a full 94% of students used those services last year.

Students also appreciate how the significant investment of career counselors improves their professional prospects. While fifteen years ago, 51% of students were satisfied with career counseling (and 9.9% of these were “very satisfied), satisfaction has grown steadily over time with 60% satisfied in 2009, 64% in 2014, and a remarkable 69% satisfied in 2019 (with 22% of those noting they are “very satisfied”). As with academic advising, higher percentages of students are taking advantage of career counseling—only 8.0% of students in 2019 did not use this service (compared to 15% in 2004).

The vast majority of students sought assistance with the job search in 2004 and in subsequent years. While almost half (49%) of students were satisfied with staff efforts to provide job search help in 2004, those numbers have increased over time to 56% in 2009, 60% in 2014, and now to 66%. Although there is room for improvement, students are noticing and appreciating improvement over time.

The Changing Landscape of Legal Education: Positive Learning Outcomes

Over the past fifteen years, LSSSE has documented dramatic changes in legal education. From 2004 to 2019, the changing landscape of law school was punctuated by increasing diversity among students, rising debt levels, relative consistency in job expectations, and improvements in various learning outcomes. In spite of many challenges, law students nevertheless report relatively constant positive levels of satisfaction with legal education overall. Our 2020 special report The Changing Landscape of Legal Education: A 15-Year LSSSE Retrospective shares longitudinal findings on select metrics as well as demographic differences within variables to catalog how legal education has changed over time. In this blog post, we will share how students have increased their achievement of selected learning outcomes from 2004 to 2019.

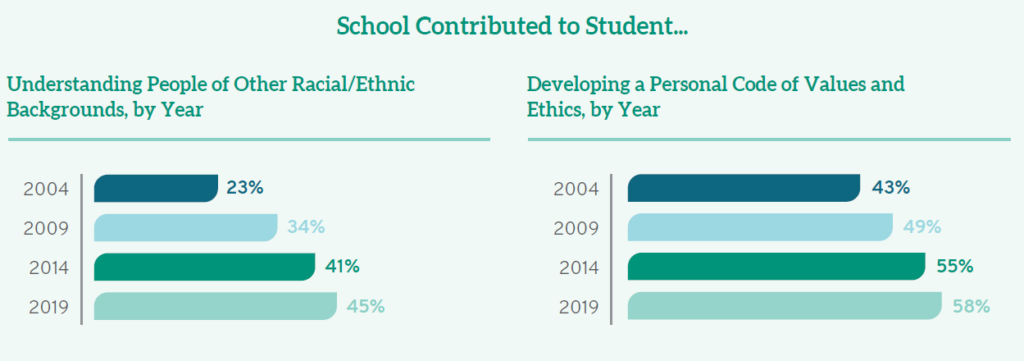

According to LSSSE data, law schools contributed to increases in a variety of perceived learning outcomes from 2004 to 2019; collectively, these point toward progress in terms of how students measure their own skills and likely in terms of actual practice-readiness of graduates. In 2004, only 23% of students saw their schools as doing “quite a bit” or “very much” to help them understand people of other racial and ethnic backgrounds; because of steady increases over the next fifteen years, especially between 2009 and 2014, almost half (45%) of students today see their schools as doing “quite a bit” or “very much” to prepare them to interact with racially diverse colleagues and clients.

In addition, schools have increased their emphasis on professional responsibility in the past fifteen years. While even in 2004 a full 43% of students saw their schools as doing “quite a bit” or “very much” to encourage them to develop a personal code of values and ethics, that number has now grown to 58%. Schools were already prioritizing complex problem solving fifteen years ago, and students see institutional support for this skill growing over time as well. While in 2004, 12% of students believed their law schools contributed “very much” to their ability to solve “complex real-world problems,” that percentage has doubled over fifteen years so that now almost a quarter (24%) of students agree. Law schools are also encouraging students to focus on developing career goals and aspirations. In 2004, almost a quarter (23%) of all law students saw their schools doing “very little” to contribute to their developing clearer career goals; by 2019 those statistics dropped to 14%. On the flip side, while only 11% saw their schools doing “very much” in this regard in 2004, that number has risen steadily, reaching 22% in 2014 and remaining there in 2019.

Looking at the past can help prepare us for our future. To learn more, you can read the entire Changing Landscape report here.

How Many Law Students Are Following in Their Lawyer Parent’s Footsteps?

Why and how do people choose their course of study and their future career? While status, compensation, and personal values likely play an important role in choosing a career, there may also be an influence of family tradition. We used LSSSE data from 2019 and 2020 to ask how many law students have at least one lawyer parent and to see whether these students differ in appreciable ways from their classmates who were not raised by a lawyer.

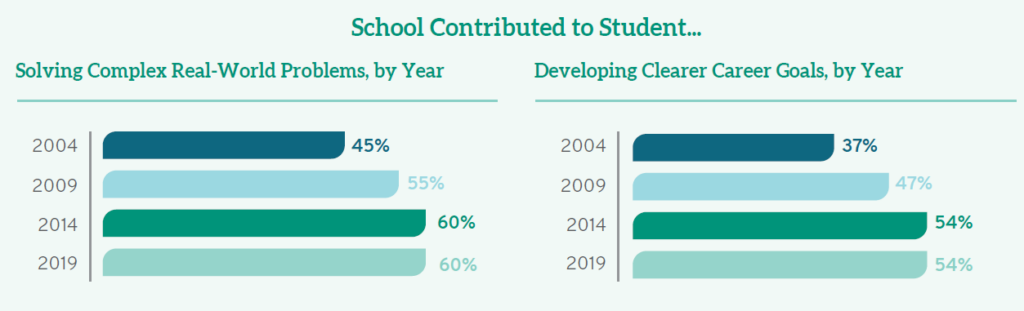

Law students tend to have educated parents. Around 73% of LSSSE respondents have at least one parent with a bachelor’s degree or higher. One in five students (20%) have at least one parent with a doctoral or professional degree (PhD, JD, MD, DDS, etc.), and among those students, just over half (53%) report that the doctoral degree is a JD. Overall, 11% of LSSSE respondents have a parent with a JD.

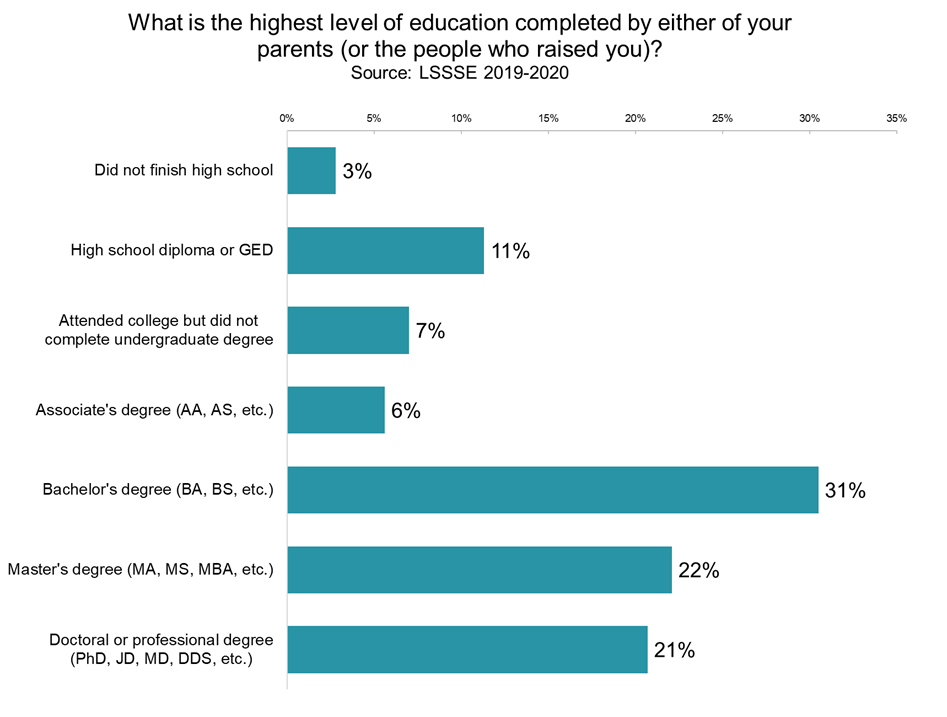

By and large, law students are satisfied with their experiences at law school, and we see minimal differences in satisfaction by parental education. If we combine “good” and “excellent” ratings, satisfaction is 84% among students who have at least one parent with a JD, 83% among students who have at least one parent with a different doctoral degree, and 81% among students whose parents do not have doctoral degrees. Students who have at least one parent with a doctoral degree may be slightly more likely to choose the highest rating (38% vs. 35% among students with non-doctorate parents).

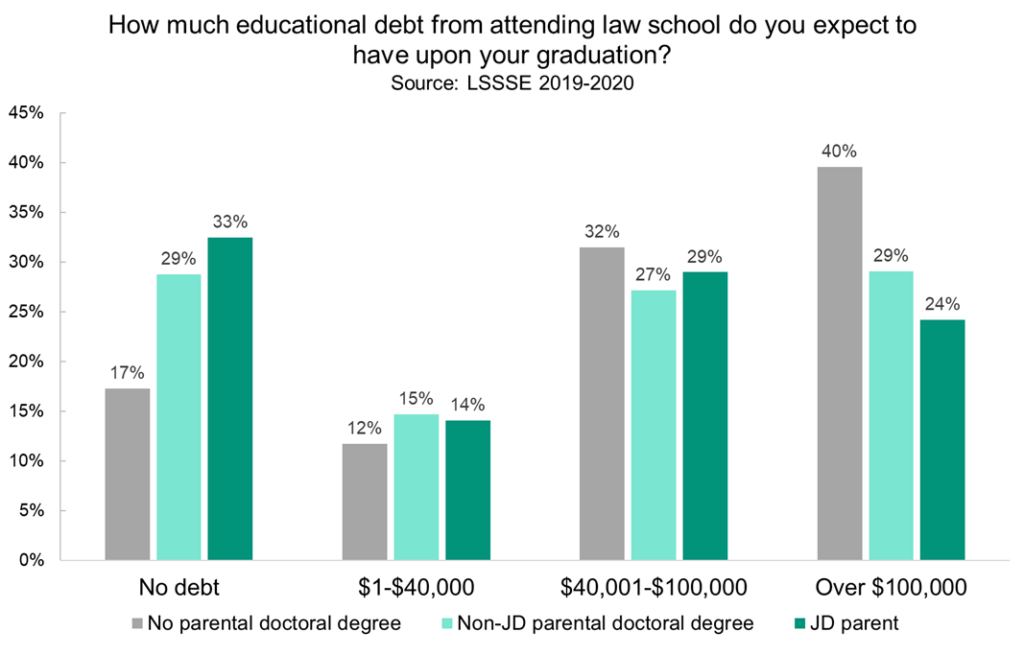

We do, however, see large differences in expected law school debt based on parental education. Students with less educated parents are much more likely to expect to owe more than $100,000 upon graduation and much less likely to graduate debt-free than their classmates with more educated parents. On some level, this may make sense, given that parental education is a strong predictor of a students’ socioeconomic status. However, it remains deeply problematic given that law school debt disadvantages students from lower income households and minimizes upward economic mobility, particularly among students of color. Interestingly, compared to their counterparts whose parents have non-JD doctoral degrees, students with JD parents are still less likely to owe over $100,000 and are more likely to graduate debt-free. If we assume socioeconomic status is roughly equivalent among parents with doctorates, then there may be some advantage to having a lawyer parent, either by increased parental investment in the students’ education or by a keener insight into navigating the process of financing a legal education.